Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: Dead Space

- Sprache: Englisch

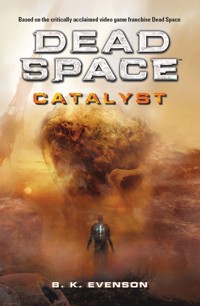

A prequel to Dead Space, the novel focuses on the Black Marker. This novel set centuries before the events of the main series, elaborates on the lore of the Markers established in Dead Space 2 and 3. Two hundred and fifty years in the future, extinction threatens mankind. Tampering with dangerous technology from the Black Marker—an ancient alien artifact discovered on Earth eighty years earlier— Earthgov hopes to save humanity. But the Marker's influence reanimates corpses into grotesque rampaging nightmares. Steeped in desperation, deceit, and hubris, the history of the Markers reveals our ominous future…. Brothers Istvan and Jensi grew up under the poorest dome on Vinduaga. Jensi has always looked after Istvan, who sometimes lashes out in sudden episodes of violent paranoia. When Istvan is sent offworld to a high-security prison, Jensi is determined to follow and find a way to keep his brother safe. But the prison guards a horrible secret, one that will push both brothers to the cusp of something much greater and darker than they ever imagined.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 447

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Part Two

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Part Three

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Part Four

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

ALSO BY B. K. EVENSON

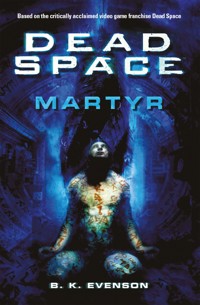

Dead Space: Martyr

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

Dead Space™: Catalyst

Print edition ISBN: 9781835414361

E-book edition ISBN: 9781835414385

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group

144 Southwark Street

London

SE1 0UP

First edition May 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright ©2012, 2025 Electronic Arts Inc. All Rights Reserved. Electronic Arts, Dead Space, and Visceral Games are trademarks of Electronic Arts Inc. All other trademarks are property of their respective owners.

All Rights Reserved.

This is a work of fiction. Names, places, and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

www.deadspacegame.com

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

EU RP (for authorities only)

eucomply OÜ, Pärnu mnt. 139b-14, 11317 Tallinn, Estonia

[email protected], +3375690241

Typeset in Adobe Caslon Pro.

When he was young, Jensi Sato had no idea that anything was wrong with his brother. Istvan had always been the way he was—always a little off, obsessed with patterns and numbers, entranced by shifts in light, prone to sudden fits of rage or mental absence. Or he had changed so gradually that Jensi, around him every day, hadn’t noticed how different he had become.

As boys, they roamed the projects together, raising hell, heads always aching from breathing the thin, imperfect atmosphere of the dome they lived in on Vindauga. Really, it was Istvan raising hell and Jensi, younger, following along. But Jensi was glad to be included. And even if he didn’t always quite understand why Istvan did what he did, he did want to get out of the house, did want to get away from their mother.

By the time he was in his teens, Jensi had begun to see how different Istvan was. His brother wasn’t like other people. Most of the time, he didn’t know how to talk to other people, and when he did the things he said didn’t have the effect he thought they would. He saw how the other boys looked at Istvan strangely, how they drew away from him, then from both of them. Soon Jensi and Istvan were pretty much left to themselves.

It wasn’t as easy as saying that Istvan wasn’t normal, because in basic ways he was, more or less. He could get by if he had to, could usually make his way through brief and ordinary interactions without a tremor. But the more time you spent around him, the stranger he seemed. He lived in his own world, always getting caught up in the shapes and patterns he saw around him—patterns that Jensi often couldn’t see. Istvan grew frustrated with other people quickly. He was less able to pay attention to others. It never occurred to him to care what other people thought of him, and he also wasn’t afraid. Really, the only person he ever listened to was Jensi, and he only listened to him sometimes, only reluctantly letting himself be coaxed out of real trouble.

* * *

At age twelve, Jensi was out with Istvan, wandering through the compound where they lived, searching for something to do. The Mariner Valley compound was kept separate from the larger domes that comprised the rest of the town by a tube, and it was only later that Jensi realized this was because they lived in low-income housing into which all the undesirables on Vindauga were pushed.

That day, there had been a half dozen children a few years younger than them crouched near the outer wall of the dome, near a place where the inner wall had been cracked and rendered opaque. There was a slow leak there, quickly compensated for by the dome’s oxygen protocol. The kids kept daring one another to get close to it. Holding their breath, one of them would run to the dome wall, touch the opaque section, and run back. The others would slap him on the back in congratulation and then would push at another boy until he did it, too.

“What kind of game is that?” asked Istvan, directing the question to none of them and all of them at once.

Most of the boys just ignored him, looking away as if they hadn’t heard. One, the biggest, just shrugged. “Just something to do,” he said.

“But it’s not even dangerous,” said Istvan. “How can it be fun pretending something’s dangerous when it’s not?”

Jensi put his hand on his shoulder. “Come on,” he said. “Leave them alone. Let’s go.”

But Istvan shook the hand off. “Don’t you want to play a real game?” he asked them.

Defensive, the leader of the boys said, “It is a real game.”

“No,” said Istvan. “It’s not. You can’t just run up close to it and run back. It’s calling you to perfect it. That’s the game it wants to play. Can’t you see the shape is wrong?”

“It?” said one of the boys. “What do you mean?”

Isvtan gestured toward the damaged section of dome. The boys glanced that way and Jensi followed their gaze. What would make the shape of it right or wrong? he wondered. What was Istvan seeing?

“Do you want to see a real game?” asked Istvan.

The boys stayed huddled together, arms crossed, silent.

“Come on,” said Jensi again to his brother. “Let’s go.”

“It doesn’t matter if you want to see or not,” said Istvan. “It wants to play.” He leaned forward, locking his arms behind his back. He pawed the filthy ground with his feet and then, suddenly, screaming, he charged.

The group of kids scattered. But he wasn’t aiming at them. He rushed past them without a glance and ran smack into the opaque portion of dome wall, his forehead striking it hard. Jensi felt his heart leap in his throat.

There was a hiss, and the cracks worsened, the shape of the opaque section expanding, but the plate, luckily, did not give. Istvan, though, did give, collapsing in a heap, his forehead smeared with blood. The scattered boys re-formed and stood huddled at a distance. Jensi ran quickly forward, knelt beside his brother.

“Istvan?” he said, shaking him. “Istvan? Why would you do that?”

Blood dripped slowly from his forehead. For a moment Istvan’s eyes were glazed and loose in the sockets, and then they slowly focused on his brother. And then he smiled and let his gaze drift back to the opaque part of the wall. “There,” he said. “Now the shape is right. Now we know what’s really there.”

* * *

Jensi had tried to ask him about it later, but Istvan had been unable to explain in a way that Jensi could follow. Istvan’s brain was always hunting for patterns, always making connections that Jensi had a hard time seeing himself. Istvan had seen the crack in the dome and had known, he claimed, what he needed to do. The crack had called to him. He knew what it wanted him to do and what it would take to make it whole.

“What the hell’s that supposed to mean? Make it whole?”

Istvan had tried to explain, but he just couldn’t. His attempts at making sense of his thinking for Jensi just led him further and further into confusion until Jensi finally stopped him.

“Look,” he finally said. “You sound crazy. You shouldn’t tell anybody this.”

And for once his brother listened, and stopped talking. Which made it so that any hope that Jensi had of figuring out what Istvan meant was drastically reduced.

* * *

When Jensi was fourteen, a group of girls chalked on the ground an old game one of them had read about in the vid library: a series of numbered squares, all connected, that you had to hop through, skipping squares according to a predetermined pattern. The girls were standing around the game, arguing about how you knew which squares you had to skip. Istvan, though, had been drawn by the numbers in the squares, his head rapidly swiveling from one to the next. He had simply walked through the group of girls, almost as if he didn’t notice them. He knocked one of them down, scattering the handful of rocks they had gathered, crushing the chalk. The girls were yelling at him, the one on the ground crying and holding up her skinned elbow accusingly, but Istvan was now standing over the squares. Gingerly, he stepped into one, then leaped into another, then leaped back, following a complex pattern that only he could see until with a final leap he came to the top of the game and stepped carefully out again.

Once out, he stopped as if paralyzed. He stared at the uneven ground past the game. Jensi, not knowing what else to do, went to him.

“That was mean,” he said.

But Istvan didn’t answer. Instead he squatted and brushed his finger along the ground, tracing an irregular shape on it.

Angrily, Jensi batted his brother’s shoulder. “Hey,” he said. “Why did you have to be so mean to them?”

“Don’t you see it?” said Istvan. “How they drew the right pattern and then it led me here?” He traced the shape again, his eyes gleaming. Jensi, squinting, could barely make out what Istvan was looking at, an unevenness in the ground, a tusk-shaped discoloration that made the ground just slightly different. “It’s perfect,” said Istvan, and reached down to stroke it again.

“Istvan,” said Jensi. “What’s wrong with you? It’s just the ground.”

“Huh?” said Istvan. “What?” It was like he was coming out of a trance. Quickly he stood up. Then he turned and looked back at the girls. They stood with their hands on their hips, still angry, though no longer yelling. “What’s wrong with them?” he asked.

“You ruined their game.”

“I did?” said Istvan. He seemed genuinely puzzled, as if he really didn’t remember. He stayed staring at them a moment, then his features grew hard. “They didn’t know what they were playing,” he claimed. “I’m the only one who knows.”

* * *

Jensi thought of the many times he had woken up in their bedroom late at night to hear his brother. Istvan would be mumbling, talking in his sleep, but the same pattern of words would be repeated over and over again, endlessly. Or he would be sitting on the edge of his bed, somewhere between sleep and wakefulness, rocking back and forth, rattling about a sequence of numbers, his voice almost worshipful. He was like that; he loved numbers and patterns, could get lost in them. They were almost like people to him, but people were less interesting. He also seemed to pick up things naturally about computers, had been hacking since he was nine, and had taught Jensi how to do the same. But here it was numbers, mumbled, repeated again and again.

“Istvan,” Jensi would whisper. But Istvan wouldn’t hear him.

Sometimes Jensi was lucky and his brother would simply stop on his own. Other times, though, he threatened to rock back and forth forever. Jensi would get up and shake him but sometimes even that wouldn’t stop him. It was as if he were elsewhere, as if he had stepped outside of his body for a while. Sometimes it took a very long time for him to step back in.

* * *

I should have known, thought Jensi once he was grown. I should have known how wrong things were for him. I should have known how damaged he was. I should have tried to get him help. I should have been able to save him.

But how—another part of him wondered, a part he tried hard to suppress—how could he have known? He was the younger brother, after all. There was only so much he could do. And his mother, no, she didn’t believe in doctors, thought that God would sort everything out on his own and that you shouldn’t interfere. He had, actually, tried several times to tell her that something was wrong with Istvan. But each time she had looked up at him with bleary eyes.

“Wrong?” she said. “Of course there’s something wrong with him. He’s evil.”

“No,” he said. “Something’s gone wrong inside of him. Something’s wrong with his mind.”

“Evil is in him,” muttered his mother. “He needs to have it driven out.” And then, with horror, he realized that he’d given his mother an excuse to hurt his brother.

But as Istvan grew older and bigger his mother started leaving him alone. She would curse him from the other side of the room, tell him that he was vile, but she no longer touched him. She was a little afraid of him. And that meant she no longer laid a finger on Jensi, either. She became more and more withdrawn. Or maybe she had always been that way and Jensi hadn’t realized. Had Istvan gotten whatever was wrong with him from her? Was it something genetic, something inherited? And did that mean that Jensi might have it inside himself as well? No, he didn’t want to be like his mother. He didn’t want to be like his brother, either, but he loved his brother, felt responsible for him. Istvan had always looked out for him. Maybe now, now that his brother was becoming strange, it was Jensi’s turn. It was time for him to look out for his brother.

* * *

Istvan was seventeen, Jensi fifteen, when things started to go seriously wrong. It started with their mother.

They had come back from another day of wandering through the Mariner Valley compound. When they arrived, their apartment door was ajar, their mother’s passkey lying on the hall floor. They pushed open the door and saw a spill of dropped assistance packages, their mother lying in the middle of them, her body shivering.

Jensi crouched down beside her. He tried to turn her over to see her face, but it was hard. Her body was stiff, resistant.

“Help me, Istvan,” he said to his brother.

But Istvan just stayed where he was. He was looking not at his mother, but at the packages. Jensi watched him mumble, gesture at them with his finger, tracing a figure through the air.

“Istvan,” he said again. “Help!”

But Istvan was in a trance, mesmerized by the pattern made by the fallen packages. He was muttering under his breath, and then his eyes traced the pattern round again and then began to stare into empty air. Their mother, Jensi saw, was foaming at the mouth. The foam was red-flecked and he could see between her teeth and lips her tongue, partly bitten through.

“This is serious,” he said. And when Istvan still didn’t respond, he screamed his brother’s name.

His brother flinched, then shook his head, then looked down. His expression was unfathomable.

“She might die,” said Jensi.

“Yes,” said Istvan, but he made no move to help. “Don’t you see him?” he asked slowly.

“See what?” asked Jensi.

“The shadow man,” said Istvan. “He’s choking her.”

The shadow man? “Istvan,” said Jensi slowly. “Go to the vid and call emergency.”

And slowly, almost like a sleepwalker, not taking his gaze away from the boxes, Istvan did.

Jensi held his mother, talked to her, and stroked her face until the emergency crew arrived. He massaged her jaw over and over until it relaxed enough to release her tongue and then he turned her head to the side so she wouldn’t choke on the blood. Istvan, after making the call, simply stood on the opposite side of the room, watching. He refused to come close. The shadow man? wondered Jensi. What did he mean by that? He was crazy.

If I hadn’t been here, thought Jensi later as they took his mother away, Istvan would have let her die.

* * *

Istvan had come through the door only to stop stock still, breathless. There it was, he could see it, the same pattern, just the same, glimmering. He had seen it so many times before, again and again, just waiting for someone to come along and see it and put it together—just waiting for him to come put it together, because the world called to him in a different way than to others. There was his mother, lying sprawled on the floor, but that wasn’t important, she wasn’t important. She wasn’t part of the arrangement. She didn’t tell him anything about what was real. She was just in the way.

No, what was important were the things she had been holding and the way they had fallen when she had dropped them, the way that each of them, tumbling out of her hands, had found its true and proper place. Things were like that. They told him something. They gave him a rough sketch of something else, something grander, something hidden. He could feel it, sense it, but it was far away, too deeply buried to make out completely. So he could only have this, this arrangement of packages that marked out something else, pointed to something else that he could almost see but couldn’t quite.

Only maybe he could have more than that.

He held himself very still. He held his breath. He stared as hard as he could, letting his eyes follow the lines between things, connecting them, spinning from object to object. He could begin now to see the blaze of the lines of connections, was beginning to peel back the cover of the world and peer inside.

His brother was saying something, calling to him, but Istvan couldn’t hear him, couldn’t pay attention, because no, this was important, something was really happening.

For among the lines and between them he could see something beginning to emerge. A shape. A shadow that at first he mistook for his own shadow. But was it his own shadow? It didn’t seem to belong to him exactly. It was attached to him, sure, but he didn’t feel as though he were controlling it. It was its own creature. It was bound up in the objects around it and was, he realized, looming over his mother as well. It was a shadow but it was also a man, a man but also a shadow.

He moved his hands to try to touch it. When his hands moved, the shadow moved as well and placed its hands around his mother’s neck. Then it turned its smoky mouth toward him and spoke.

Watch this, it said. Here’s how you do it. Here’s how you’ll kill her.

He heard his brother scream his name.

He could not move his hands. The shadow man was choking his mother, smiling, but no longer speaking. Why had he stopped speaking? “She’s going to die,” he heard a distance voice say, a voice that was not the shadow man, a voice that he realized belonged to his brother. He made an effort of will and spoke.

“Yes,” he said. “Don’t you see him?”

But when he tried to explain to his brother what it was he saw, just as when he’d tried to explain so many times before, it came out in ways that he understood but his brother did not. Jensi did not think right about the world. Istvan was helpless to make it make sense for him. And so, slowly, he was snapped again out of this world of arrangements that he so loved and that so loved him, and brought once again to see not the pattern beneath things but the surface of them. And on that surface was his mother: dying. But, unfortunately, not already dead.

* * *

By the time the emergency team took her to the hospital, Istvan seemed normal again, or as normal as he ever was. She was there a day, then was transferred to a mental ward, strait-jacketed, put away for what potentially could be for good. A social worker, a severe elderly woman, came out to the house and told the two brothers that they would be taken into governmental care.

“But I’m almost eighteen,” claimed Istvan in a moment of lucidity. “I don’t need a guardian.”

“Almost doesn’t count,” she insisted. “You have to have one.”

But the mistake the social worker made was leaving them alone for a few minutes instead of whisking them into care immediately. As soon as she was gone, Istvan began to make plans for leaving. He got an old, stained backpack out of the closet, stuffed it full of clothes, then dumped in a random assortment of things from the pantry, including things that he would never eat. Other things that were more edible he left where they were, adjusting their positions slightly. All part of making the pattern, Jensi couldn’t help but think. Istvan was in his own world, unaware of anything but the task he was completing. Jensi just stood watching him, feeling a greater and greater sense of despair for his brother.

When he was finished, Istvan zipped the backpack closed and looked up.

“Why aren’t you packed?” he asked Jensi.

“Where are you going?” Jensi responded.

“You heard that woman,” said Istvan. “She wants to put us with someone. We’ll have to learn how they think and they’ll be like mother only they’ll be worse because we’re not related to them.”

“Maybe they won’t be worse,” said Jensi. “Maybe they’ll be better.”

Istvan shook his head. “That’s what they want you to think,” he said. “That’s how they get you every time.”

That’s how they get you every time, thought Jensi But it was not they that were getting Istvan, but Istvan who was making things hard for himself. The idea of Istvan being his own guardian—or being the guardian for both of them—that would never work. Istvan could hardly care for himself, let alone someone else.

“Come on,” Istvan said. “No time to pack—they’ll be back soon. You’ll just have to go as you are. That’s what the room is saying.”

“The room?”

“Can’t you see it?” said Istvan, gesturing around him. “Can’t you feel it?”

Later, this would seem one of those decisive moments where his life could go either one direction or another, where Jensi could take a step toward his brother and whatever skewed version of the world existed inside of Istvan’s mind or where he could step closer to the real world. The terrible thing was that even as young as he was he couldn’t help but feel that either choice he made would be, in some way or another, not quite right. Either way he would lose something.

“Come on,” said Istvan again, anxious.

“I . . .” said Jensi. “But I—”

“What’s wrong with you?” said Istvan. “Can’t you see what’s happening here?”

But that was the problem: he could see. He could see that if he went with Istvan no good would come of it, even if Istvan could not.

“I can’t go,” he finally said, not looking his brother in the eye.

“Sure you can,” said Istvan, his eyes darting all around the room. “It’s the easiest thing in the world. All you have to do is walk out the door.”

“No,” said Jensi. “I’m sorry. I’m not going.”

For a moment Istvan just stared at him, his face blank, and then Jensi watched something flit across his brother’s expression as he took in what Jensi was saying. Then all at once his face was creased with genuine pain.

“You’re abandoning me?” he asked in a voice that was almost a wail. It was nearly unbearable for Jensi to hear.

“No,” Jensi tried to say. “Stay here. Stay with me. It’ll be okay.” But he knew that to Istvan that was as unimaginable as leaving was to him. For a moment Istvan looked stunned. And then, heaving the backpack onto his shoulder, Istvan went out and Jensi found himself alone.

Nothing was really wrong about the guardian the court appointed to Jensi, but nothing was all that right about her, either. She was what his mother might have called the lukewarm, neither one thing nor the other, but for Jensi that was all right. He could survive with someone like that. He could get by. For once in his life he didn’t have to worry about where his meals were going to come from.

He threw himself into his schoolwork and was surprised to find that he enjoyed it, that he even excelled at it. The sort of kids who before had given him a wide berth now began to circle closer, sometimes even speaking to him.

One of them, a kid named Henry Wandrei, started hanging out around him, silently standing a few feet away from him during breaks between classes, sitting across from him at lunch but at first without speaking or meeting his eye. Sometimes he shadowed Jensi for a few blocks when he walked home. At first Jensi tolerated it, then he got used to it, then he started to like it. He started to notice when Henry wasn’t there, like his shadow or ghost.

“What?” Jensi finally said one day at lunch.

“Nothing,” said Henry. And then they sat silently for a while until Henry asked “What music do you like?”

Music? wondered Jensi. What did he know about music? Helplessly, he just shrugged. “What about you?”

Henry rattled off a few names of bands, then when Jensi didn’t say anything in reply, began to try to explain what each one sounded like. He was, as it turned out, good at it, capable of talking in a lively and surprising way that didn’t really describe the music so much as say something slantwise that still gave a sense of what it sounded like. Jensi was surprised to find he enjoyed listening to him talk. Henry, silent for so long, now seemed unable to be quiet. And later, when he gave Jensi the music to listen to, Jensi found that the descriptions felt right.

Henry was his first real friend, apart from his brother. But you couldn’t really think of a brother as a friend, could you? How had he gotten to be fifteen before having a real friend? Thinking that made him resent Istvan, which made him feel guilty. Here he was, living an okay life, with a decent guardian and one real friend, while his brother was wandering alone somewhere out in the domes.

He had glimpsed his brother once or twice, usually from far away though once up close. That time, his brother had seemed not to know him. Istvan had not acknowledged him as he went past, and though Jensi wanted to reach out and speak to him, he hadn’t been able to bring himself to do so. He couldn’t, not if Istvan wasn’t going to meet him halfway. But later he wondered if his brother hadn’t simply been lost in his private world of patterns and numbers. Maybe his brother was so deep within his own head that he couldn’t see Jensi.

His life was like that in those days. It was like he was on a teeter-totter, slipping from feeling all right to feeling guilty and then back again, but never stabilizing.

After a few months he trusted Henry enough to tell him about Istvan.

“That’s your brother?” said Henry. He’d seen Istvan here and there, always from a distance, and didn’t quite know what to think of him.

“I feel like I should help him,” said Istvan.

Henry nodded. “Sure,” he said, “he’s you’re brother. You have to feel that way.” And then he shrugged. “But what can you do?” he asked.

* * *

For six months he did nothing, really, and then one day, walking home, he was talking with Henry about the apartment building he used to live in, trying to describe it as vividly as Henry had managed to describe not only music but other things since, and finding himself failing to make it come alive. Henry was watching him politely, eagerly even, but he kept tripping and stumbling over his words, unable to make them into images that Henry could understand. Slowly he ground to a stop.

Henry watched and waited for him to continue, and when he didn’t simply said, “You could just show it to me.”

Jensi thought Why not? So they trekked the mile or so over to the valve that led to the Mariner Valley compound.

The valve operator stationed there stared at them quizzically. “You sure you want to go in there? Two nice kids like you?” he asked from beneath a bristling mustache. “It’s a little rough.”

“I used to live there,” said Jensi.

The operator wrinkled his nose. “If I’d lived there and gotten out, I don’t know that I’d be eager to go back.” But he let them through.

They watched the valve twist closed behind them, and then walked the thirty meters down the tube to the second valve. By the time they got there, Jensi was beginning to have his doubts. He had a new life now, he should be moving on. Why would he want to show any of this to Henry?

* * *

The valve twisted open and they stepped out. To Jensi the compound on the other side looked at once familiar, just as he remembered it, and different, too. Having changed himself, he could see it for what it was: a slum. The valves were a way of cutting off the Mariner Valley compound in case the people inside decided to revolt. The streets that had seemed normal to him as a child he could now compare to the streets where he currently lived. Everything was run-down, a little filthy, a little pathetic.

“You lived here?” asked Henry.

Jensi shrugged. For a moment he considered turning around, going back to the valve and leaving, but then Henry asked, “So, where’s your building?”

* * *

He showed Henry the worn concrete steps, the cracked floor of the hallway leading down to their apartment, and then the door itself, discolored and scraped ragged along one side. They stared at it. Jensi didn’t know what else to do, and Henry didn’t seem ready to go back yet. The door was sealed where it met the frame with police tape. Why? wondered Jensi. He was surprised that someone new hadn’t moved in by now.

But looking more closely, he realized the tape had been slit, very carefully, so that at first glance the door still looked like it was sealed. Henry must have realized that as well, for he reached out and placed his hand on the door’s handle and pushed down.

The door was not locked. As both boys watched, it slid slowly open. Behind it was the largely empty living room, floor coated now with a thin layer of dust. There was the uneven couch, the small vid screen with its cracked corner, the makeshift coffee table made from a discarded and bent shipping container that they’d found and then beaten back flat. The wall was discolored, now beginning to go gray with mold in the corners, unless it was just dust gathering there.

“We probably shouldn’t be here,” said Jensi. The memories in the room were palpable to him, most of them bad.

“It’s okay,” said Henry, already poking around. “There’s no one here. Even if someone comes, we can talk our way out of it.” For Henry, Jensi realized, it was a game.

And then Jensi noticed the path that had been scuffed through the dust from the front door to the entrance to the back bedroom, the room he and Istvan had shared. He followed the path with his eyes. He could see a light coming from the crack under the bedroom door.

He reached out and grabbed Henry’s arm.

“What?” asked Henry, starting to shake free.

“Quiet,” whispered Jensi. “I think someone’s here.”

* * *

If he’d only turned and left, things might have been different. But he didn’t. Why? Perhaps it was because Henry was there with him and that, for Henry, this was still an adventure. Knowing someone was there made it even more of an adventure for Henry. It was simply an escalation of the violation that had begun when they found the police tape slit over the door. They were sneaking in, and now they were risking something, but from Henry’s perspective probably the worst that could happen was they might get scolded or warned off or kicked out. Or maybe, at very worse, turned in to the authorities for trespassing and then released with a reprimand.

But Jensi had grown up in this neighborhood. He knew it could be much worse, that if the wrong person was in the back room they might end up badly hurt or even dead.

And so when Henry started moving forward, deeper into the apartment, Jensi was not quick to follow. He watched his friend go, his feet tracking a new path through the dust until he stood beside the bedroom door. Maybe, thought Jensi, there would be nobody there. Maybe someone had come and gone but left the light on. But as Henry reached out and touched the door’s handle, Jensi knew that he was fooling himself.

And indeed, before Henry could open it, the door opened of its own accord and a blotchy arm reached out and jerked him through.

* * *

Jensi started for the outer door, already beginning to run.

But there was nowhere to run, nobody to tell until he had gone through the valve and into the larger city. By then it would be too late. Henry would either be dead and lying broken on the floor when he got back, or he would have been carried away and would be gone.

And so, barely out the door, his feet slowed, he stopped, and he turned back. He was big enough, he told himself, and tough, too, and he had grown up here and knew how to fight. If he could just get a jump on whomever it was, there might be a chance for both him and Henry to get away.

He quietly approached the door to the bedroom and carefully pushed the handle down until the tongue slid out of the lock’s groove. He could hear a voice inside, whispering, insistent. Taking a deep breath, he threw the door open and rushed in, fist already cocked and ready to strike.

On the floor, kneeling on top of Henry, holding him down, keeping him from struggling, hand clamped over his mouth, was a filthy man. His hair and skin were wretched and stinking. Who sent you? he heard him whispering loudly, without lifting his hand from Henry’s mouth to let him answer. What do they want from me? Why are they after me? And then Jensi was on the man, clipping him in the ear and knocking him enough askew that he turned and shifted his balance and Henry began to wriggle free.

But at the same moment the man turned, and Jensi was surprised to find that his was a face he recognized.

It was Istvan.

But though he recognized Istvan, his brother didn’t recognize him. His eyes were glazed, crazed even, and as he half fell, half clambered off Henry, it seemed almost like his brother wasn’t there at all. It was like it was just his body but with someone else or even something else in charge.

Henry had managed to scramble to his feet. Isvtan, stumbling, gathered his balance against the wall and then bared his teeth.

“Istvan,” said Jensi. “It’s me.”

Istvan made a noise that was a kind of snarl, his eyes darting everywhere, looking perhaps for some hidden pattern but as a result unable to see what was in front of him, and then he ducked his head and charged.

He struck Jensi hard, right in the center of the chest, knocking him off his feet, coming down hard on top of him. For a moment, Jensi had the awful feeling of suffocating, the room fading around him, and then he managed to suck in a deep, pain-racked breath. Istvan was on top of him, striking out, pummeling his shoulders and neck and face with his fists. Henry was behind him, trying and failing to tug him off.

Istvan, he tried to say again. It’s me, Jensi. But nothing came out. He tried to grab Istvan’s hands but failed. He tried to protect his face with his forearms, but Istvan kept punching him, the blows glancing off his arms but sometimes getting through, with Jensi catching here and there a glimpse of his slack, troubled face.

There was a moment when he thought he was about to fade from consciousness, and then it passed and his mind suddenly felt sharper but also more distanced, as if he were observing himself from the outside.

He suddenly realized that Istvan might very well kill him.

* * *

Istvan had been searching for something for a while, though he was never quite sure what. It was often like that, aimless, but he knew if he searched long enough it would eventually nudge its way out from the world it resided in, the world that was real, and come find him. Before, when his brother had been there, there had been things to pull him out, to interrupt his search, so that only rarely could he wait long enough for the surface of the world to peel back. But now he had all the time in the world.

The first thing was to limit the world itself, to get rid of all unnecessary distractions. Of anything and everything that did not encourage an arrangement that would crack the world open. Being out in the dome proved too much. There were signs and symbols there, patterns of all kinds, but they drew him in all directions at once. There were people there too who shook him and disturbed him and would not let him stay put.

A pattern, an arrangement, out in the dome had led him back to his mother’s apartment again, just as a pattern, an arrangement, in the apartment had first coaxed him out into the dome. A voice had come to him and told him to slit back the tape sealing the door and told him too where his mother had hidden the key that would let him in. It was a voice that was not attached to a body, or if it was, he couldn’t find the body. It was a voice that somehow was inside of him but separate from him too.

He had left the pantry as it was, the pattern was good there, it had been made whole when he had left, though it was not complete in and of itself. He had arranged the couch just right. The coffee table he had left as it was, but he had used his fist to dent it further until his fist was bloody, and then had stared at his distorted, gray reflection in its surface. There, he thought, the shadow man, and waited for him to come out.

Only he didn’t come out. If it was the shadow man—he could not be sure if it was or was not, not yet, not until he came out. Maybe he was too gray and was another man entirely. Or maybe it was nothing at all. And so, sitting on the couch, he had waited for hours, sometimes bringing his face down close to the metal surface but still unable to coax the shadow man forth.

But after a time he had felt the pattern pushing at him. The pattern was right, but he was the one who was out of place. No, he had to be elsewhere for the pattern to do its work.

So he had stood and stepped his way across the room and into the room that his brother and he had once occupied.

There, in the bare room, he waited. When it came, it would come now to find him. He stared at the door, patient, ready for whatever would come.

* * *

How long he waited, how many hours or days, he couldn’t say. But in the end there came sounds outside and he knew the moment had arrived. He stood and pressed his ear to the door. And then when he heard footsteps approached, he yanked the door open and grabbed what was on the other side and pulled it in.

But no, it was not what he was hoping for, not what he expected. It was not something from the other world, but something from this world, an invader, an intruder, someone who had come to disrupt the pattern and to keep him from succeeding. Who had sent him? There were forces, he knew, out to disrupt him, forces that meant to keep him from finding what he was meant to find and fulfilling his purpose. They had been there at all moments, disturbing him. He shook this one, letting him know what he thought of him. To get him to tell him who was after him, who was trying to ruin him, he kept shaking, kept shaking. Yes, he told himself, he would get somewhere, he was getting somewhere.

And then something struck him hard on the head, dazing him. The invader beneath him wriggled out from under him and away and there were, he saw, at least two invaders now in the room. He scrambled up and away to face them, trying at the same time not to see them too closely, not to lose sight of the pattern, for if he lost sight of the pattern then they would win.

But there at last was the shadow man, curling there in the air, splaying from the feet of one of the intruders, the one who had struck him. The way to him was through the body of the intruder, he knew. He shook his head and then struck out and the intruder was beneath him and the shadow man was beneath both of them, being held by the intruder, but if he tried to dig his way through him then maybe he could get to him. The intruder was trying to speak, but no, he could hear a voice within his head telling him not to listen. And the other intruder was behind him now, striking him, but he was ready for that this time, he could keep his balance. It had happened, he had seen what he wanted, what he needed, and there would be no stopping him now.

There were nine of them gathered at the table. Some of them were clearly scientists, others military, others bureaucrats, still others it was hard to say exactly what they were. Most, but not all, of them were Unitologists, and here, among friends, they all wore their amulets exposed and hanging around their necks, publicly professing their creed.

“So we’re in agreement,” said one of them. He was a military man and seemingly the leader, of an impressive mien and bearing, named Blackwell. Of very high rank, his uniform studded with insignia and commendations.

“I still think it’s too dangerous,” said another, a wiry little man, a scientist named Kurzweil. “Despite all precautions, the Black Marker experiments went quickly out of control. We lost the majority of our team. We’re very lucky that there wasn’t an outbreak, that we were able to stop it within the walls of the compound.” He gestured to the scientist next to him. “Hayes can attest to that.”

“And yet, I’m for it,” said Hayes. “As is everyone here but you, Kurzweil. In any experiment there is risk, and the potential gains that we have from unlocking the power of the Black Marker far outweigh the risks. We are the vanguard meant to lead humanity to Convergence. Now that we’ve recovered the data, we should have the means to build a new Marker.”

Some of the others nodded in agreement.

“Fine,” said Blackwell. He turned to the first scientist. “You’re outvoted, Kurzweil, as you knew already.”

Kurzweil shrugged. “Can we at least agree not to build the new facility on Earth? We need to be somewhere where, if there is an outbreak, it’ll do a minimal amount of damage.”

“So where do we go now?” asked Blackwell.

“To the moon?” suggested one of the men.

Kurzweil shook his head. “Too close, not private enough.”

“We need to go somewhere where we can allow things to develop and see how they go, get as much data as possible, and then nuke the planet if need be,” said one of the men whose profession wasn’t identifiable. His hair was cut short and he had cruel eyes. His skin had a dullness to it, was almost gray. “Somewhere off the beaten track.”

Blackwell nodded. “I’ll send a ship out,” he said. “I know just the man for the job. We’ll see what he can find.”

They stood and prepared to go, but the two men without identifiable profession or affiliation beckoned to Blackwell to stay behind. He did, remaining silent with his arms folded, waiting until the three of them were alone in the room. But even once everyone else was gone, the men didn’t say anything.

“That went quite well, I think,” Blackwell finally said.

“Who do you have for the job?” asked the larger of the two, ignoring Blackwell’s comment.

“Who? Commander Grottor. We’ve used him often in the past. He has impeccable credentials and is very discreet, as is his crew.”

The other man nodded. “We’ll want to meet him,” he said.

“You’ve never asked to meet them before,” said Blackwell.

“This is much more important than anything we’ve done before.”

“Don’t you trust me?” asked Blackwell.

The two men just stared at him, as if he hadn’t asked a question.

“We’ll want to meet him,” the man repeated.

Blackwell nodded. “Of course,” he said.

Istvan seemed to be growing tired, the blows coming slower as he struggled not only to keep hitting Jensi but to keep pushing Henry away. Jensi waited, still trying to protect his face, and then, when Henry fell again on his brother’s back, he lashed out, punched Istvan as hard as he could in the throat.

Istvan started to gasp but remained solidly straddling him. Henry kept trying to pull him off. Not knowing what else to do, Jensi sat up as far as he could and wrapped his arms around his brother, drew him as close as possible.

Up close, Istvan smelled of stale sweat and something else, something gone rotten. He began struggling the moment he felt Jensi’s arms close around him, but Jensi locked his hands behind his back and held on. He pressed his face against Istvan’s neck.

“Ssshhh,” he said, as calmly as he could. “It’s okay now, Istvan. It’s okay. It’s just me.”

Istvan kept struggling. Behind him, Jensi caught a glimpse of Henry, looking puzzled now, arresting for a moment his attempts to tear Istvan off him.

“It’s me,” Jensi said, his voice a soothing whisper now. “It’s me, Jensi. It’s your brother. I’m here now, Istvan. I’m here for you.”

He kept it up, holding on as Istvan continued to try to break free. Henry had taken a few steps back, confused. Half of him seemed to want to wait. The other half seemed poised to flee. Jensi kept whispering, trying to soothe his brother, until the latter started striking the side of his face with his forehead.

He held on as long as he could, his head aching, feeling like something inside his skull was in danger of giving way. Something was wet and at first he thought he was sweating, but when Istvan’s head reared back, he saw that his brow was flecked with blood. My blood, thought Jensi. And then Istvan brought his head down again and Jensi’s hands slipped free and he felt himself pass out.

* * *

Disconnected thoughts, a strange fleeting round of faces, as if all of his past has been condensed into a particular moment, a single space. They swayed all around him and began, slowly, to spin, flitting close and then fleeing away, more like grotesque swollen birds than human faces. And then they became birds, fluttering across the sky but strangely stretching too, as if they were leaving parts of themselves behind even as they progressed forward, so that they were more like snakes than birds, only not that either. And then, as suddenly as they had come, they had faded and were gone.

In their place came a strange repeated noise, a noise which it took him a long time to realize was the sound of a man sobbing. He felt something, too. Someone shaking him.

When he opened his eyes, it was to find his brother still on top of him, but something had changed. His eyes looked different, as if there was someone else inside of the body now: human, alive. Istvan. He had a hand on either side of Jensi’s head and was caressing his face. His forehead was still smeared with blood. Henry was far behind him, huddled near the back wall, still tense, still ready to flee.

When he saw Jensi open his eyes, Istvan’s tears changed suddenly to a weird, flat smile.

“You’re alive,” he said.

Jensi struggled to sit up, managed to lift himself to his elbows. “Of course I’m alive,” he said. “Why wouldn’t I be?”

“I thought I killed you,” Istvan said.

“No such luck,” said Jensi. He straightened further and winced.

“What?” asked Henry, incredulously from near the door. “You’re friends now? Basically he just tried to kill you. We should get out of here.”

“We’re not friends,” said Jensi. “Henry, this is my brother.”

“I don’t care who he is,” said Henry. “He tried to kill you.”

“I didn’t mean to,” said Istvan.

“He didn’t mean to,” said Jensi. “He just got confused.”

“Who’s to say he won’t get confused again?” asked Henry. “Look at him. What’s wrong with him?”

“I didn’t mean to,” Istvan claimed again. “You just got in the way.”

“It doesn’t matter if you meant to or not,” said Henry. “Jensi, let’s get out of here.”

Jensi slowly shook his head. “I can’t,” he said. “He’s my brother.”

“He’s dangerous,” claimed Henry, but the steam seemed to be running out of him. He was no longer poised to run, seemed even to want to be convinced.

“He just needs to be cleaned up a little,” said Jensi. “He’s been on his own a while and he’s gotten confused. He needs someone to take care of him.”

“But why should that someone be you?” asked Henry.

“Who else is there for him?” asked Jensi. “There is only me. If I don’t help him, nobody will.”

Henry just shook his head. “It’s not supposed to work that way,” he said.

“No,” said Jensi, “but that’s the way it is.”

* * *

Quickly, he found himself feeling even more responsible for Istvan than he had before. He got Istvan to take a bath, scrubbed him down, then left him shivering and naked while he went out and found him an old but clean pair of clothes from a local church basement. But it didn’t stop there. Soon, he was scrounging up food for him, then finding scissors and trimming Istvan’s hair and beard, then stealing an old blanket or two from his foster family so that Istvan would be able to stay warm. Not knowing what else to do with Istvan, he left him there in their old apartment, hoping that the complex was unappealing enough that the apartment would remain unoccupied until he could figure out what to do with his brother.

At first, Henry would have no part of it. He followed Jensi around, trying to talk him out of helping his brother, telling him that he had a good new life and it’d be a shame to ruin it.