3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

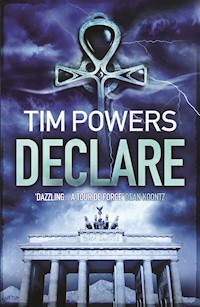

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A mesmerising, award-winning, daringly imaginative, multi-levelled thriller for fans of John le Carre or Neal Stephenson An ultra-secret MI6 codename. A deadly game of deception and intrigue. Dark forces from the depths of history. The terrible secret at the heart of the cold war. Operation: DECLARE London, 1963. A cryptic phone call forces ex-MI6 agent Andrew Hale to confront the nightmare that has haunted his adult life: an ultra-secret wartime operation, codenamed Declare. Operation Declare took Hale from Nazi-occupied Paris to the ruins of post-war Berlin and the trackless wastes of the Arabian desert, culminating in a night of betrayal and mind-shattering terror on the glacial slopes of Mount Ararat. Now, with the Cold War at its height, his superiors want him to return to the mountain and face the dark secret entombed within its icy summit. Hale has no choice but to comply, for Declare is the key to a conflict far deeper, far colder, than the Cold War itself.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

COPYRIGHT

First published in the United States of America in 2001 by HarperCollins Publishers, Inc.

This paperback edition first published in Great Britain in 2010 by Corvus, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

Copyright © Tim Powers, 2001. All rights reserved.

The moral right of Tim Powers to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This is a work of fiction. All characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

First eBook Edition: January 2010

ISBN: 978-1-848-87758-0

Corvus

An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Ormond House

26-27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

Contents

Cover

Copyright

PROLOGUE

BOOK ONE

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

FIVE

SIX

SEVEN

EIGHT

NINE

TEN

BOOK TWO

ELEVEN

TWELVE

THIRTEEN

FOURTEEN

FIFTEEN

SIXTEEN

BOOK THREE

SEVENTEEN

EIGHTEEN

EPILOGUE

AFTERWORD

AUTHOR’S NOTE

To Fr. Gerald Leonard SVD

And with thanks to Chris Arena, John Berlyne, John Bierer, JenniferBrehl, Charles N. Brown, Beth Dieckhoff, J.R. Dunn, Ken Estes, BenFenwick, Russell Galen, Patricia Geary, Tom Gilchrist, Lisa Goldstein,Anne Guerand, Varnum Honey, Fiona Kelleghan, Barry Levin,Marion Mazauric, Andreas Misera, Ross Pavlac, David Perry, SerenaPowers, Ramiz Rafeedie, Jacques Sadoul, Sunila Sen-Gupta,Claire Spencer, Tom and Cheryl Wagner, and Eric Woolery —

and especially to Jennifer Brehl and Peter Schneider and SerenaPowers, for that long discussion about Kim Philby, over dinner atthe White House in Anaheim.

Birthdays? yes, in a general way;

For the most if not for the best of men:

You were born (I suppose) on a certain day:

So was I: or perhaps in the night: what then?

Only this: or at least, if more,

You must know, not think it, and learn, not speak:

There is truth to be found on the unknown shore,

And many will find what few would seek.

J.K. Stephen, inaccurately quoted in a letter from

St. John Philby to his son, Kim Philby, March 15, 1932

Where wast thou when I laid the foundations of the earth?

Declare, if thou hast understanding.

Job 38:4

PROLOGUE

Mount Ararat, 1948

… from behind that craggy steep till then

The horizon’s bound, a huge peak, black and huge,

As if with voluntary power instinct,

Upreared its head. I struck and struck again,

And growing still in stature the grim shape

Towered up between me and the stars, and still,

For so it seemed, with purpose of its own

And measured motion like a living thing,

Strode after me.

—William Wordsworth, The Prelude, 381–389

The young captain’s hands were sticky with blood on the steering wheel as he cautiously backed the jeep in a tight turn off the rutted mud track onto a patch of level snow that shone in the intermittent moonlight on the edge of the gorge, and then his left hand seemed to freeze onto the gear-shift knob after he reached down to clank the lever up into first gear. He had been inching down the mountain path in reverse for an hour, peering over his shoulder at the dark trail, but the looming peak of Mount Ararat had not receded at all, still eclipsed half of the night sky above him, and more than anything else he needed to get away from it.

He flexed his cold-numbed fingers off the gear-shift knob and switched on the headlamps—only one came on, but the sudden blaze was dazzling, and he squinted through the shattered wind-screen at the rock wall of the gorge and the tire tracks in the mud as he pulled the wheel around to drive straight down the narrow shepherds’ path. He was still panting, his breath bursting out of his open mouth in plumes of steam. He was able to drive a little faster now, moving forward—the jeep was rocking on its abused springs and the four-cylinder engine roared in first gear, no longer in danger of lugging to a stall.

He was fairly sure that nine men had fled down the path an hour ago. Desperately he hoped that as many as four of them might be survivors of the SAS group he had led up the gorge, and that they might somehow still be sane.

But his face was stiff with dried tears, and he wasn’t sure if he were still sane himself—and unlike his men, he had been somewhat prepared for what had awaited them; to his aching shame now, he had at least known how to evade it.

In the glow reflected back from the rock wall at his right, he could see bright, bare steel around the bullet holes in the jeep’s bonnet; and he knew the doors and fenders were riddled with similar holes. The wobbling fuel gauge needle showed half a tank of petrol, so at least the tank had not been punctured.

Within a minute he saw three upright figures a hundred feet ahead of him on the path, and they didn’t turn around into the glow of the single headlamp. At this distance he couldn’t tell if they were British or Russian. He had lost his Sten gun somewhere on the high slopes, but he pulled the chunky .45 revolver out of his shoulder holster—even if these survivors were British, he might need it.

But he glanced fearfully back over his shoulder, at the looming mountain—the unsubdued power in the night was back there, up among the craggy high fastnesses of Mount Ararat.

He turned back to the frail beam of light that stretched down the slope ahead of him to light the three stumbling figures, and he increased the pressure of his foot on the accelerator, and he wished he dared to pray.

He didn’t look again at the mountain. Though in years to come he would try to dismiss it from his mind, in that moment he was bleakly sure that he would one day see it again, would again climb this cold track.

BOOK ONE

Learn, Not Speak

ONE

London, 1963

Of my Base Metal may be filed a Key,

That shall unlock the Door he howls without.

—Omar Khayyám, The Rubáiyát,

Edward J. FitzGerald translation

From the telephone a man’s accentless voice said, “Here’s a list: Chaucer… Malory…”

Hale’s face was suddenly chilly.

The voice went on. “Wyatt… Spenser…”

Hale had automatically started counting, and Spenser made four. “I imagine so,” he said, hastily and at random. “Uh, ‘which being dead many years, shall after revive,’ is the bit you’re thinking of. It’s Shakespeare, actually, Mr.—” He nearly said Mr. Goudie, which was the name of the Common Room porter who had summoned him to the telephone and who was still rocking on his heels by the door of the registrar clerk’s unlocked office, and then he nearly said Mr. Philby; “—Fonebone,” he finished lamely, trying to mumble the made-up name. He clenched his fist around the receiver to hold it steady, and with his free hand he shakily pushed a stray lock of sandy-blond hair back out of his eyes.

“Shakespeare,” said the man’s careful voice, and Hale realized that he should have phrased his response for more apparent continuity. “Oh well. Five pounds, was it? I can pay you at lunch.”

For a moment neither of them spoke.

“Lunch,” Hale said with no inflection. What is it supposed to be now, he thought, a contrary and then a parallel or example. “Better than fasting, a—uh—sandwich would be.” Good Lord.

“It might be a picnic lunch, the fools,” the bland voice went on, “and here we are barely in January—so do bring a raincoat, right?”

Repeat it back, Hale remembered. “Raincoat, I follow you.” He kept himself from asking, uselessly, Picnic, certainly—raincoat, right—but will anyone even be there, this time? Are we going to be doing this charade every tenth winter for the rest of my life? I’ll be fifty next time.

The caller hung up then, and after a few seconds Hale realized that he’d been holding his breath and started breathing again. Goudie was still standing in the doorway, probably listening, so Hale added, “If I mentioned it in the lectures, you must assume it’s liable to be in the exam.” He exhaled unhappily at the end of the sentence. Play-acting into a dead telephone now, he thought; you’re scoring idiot-goals all round. To cover the blunder, he said, “Hello? Hello?” as if he hadn’t realized the other man had rung off, and then he replaced the receiver. Not too bad a job, he told himself, all these years later. He stepped back from the desk and forced himself not to pull out his handkerchief to wipe his face.

Raincoat. Well, they had said that ten years ago too, and nothing had happened at all, then or since.

“Thank you, Goudie,” he said to the porter, and then walked past him, back across the dark old Common Room carpet to the cup of tea that was still steaming in the lamplight beside the humming typewriter. Irrationally, it seemed odd to him that the tea should still be hot, after this. He didn’t resume his seat, but picked up his sheaf of handwritten test questions and stared at the ink lines.

Ten years ago. Eventually he would cast his mind further back, and think of the war-surplus corrugated-steel bomb shelter on the marshy plain below Ararat on the Turkish–Soviet border, and then of a night in Berlin before that; but right now, defensively, he was thinking of that somewhat more recent, and local, summons—just to pace the snowy lanes of Green Park in London for an hour, as it had happened, alone and with at least diminishing anxiety, and of the subsequent forty hours of useless walks and cab rides from one old fallback location to another, down the slushy streets and across the bridges of London, cursing the confusing new buildings and intersections. There had been no telephone numbers or addresses that he would have dared to try, and in any case they would almost certainly all have been obsolete by that time. He had eventually given it up and taken the train back to Oxford, having incidentally missed a job interview; a fair calamity, in those days.

At least there was no real work to do today, and none tomorrow either. He had only come over to the college so early this morning to use fresh carbon paper and one of the electric typewriters.

Between the tall curtains to his left he could see clouds like hammered tin over the library’s mansard roof, and bare young oak branches waving in the wind that rattled the casement latches. He would probably be wanting a raincoat, a literal one. God knew where he’d wind up having lunch. Not at a picnic, certainly.

He folded the papers and tucked them into his coat pocket, then ratcheted the half-typed sheets out of the typewriter, and switched the machine off.

He hoped it would still be working right, and not have got gummed up by some undergraduate teaching assistant, when he got back—which would be, he was confident, in at most a couple of days. The confidence was real, and he knew that it should have buoyed him up.

He sighed and patted the pockets of his trousers for his car keys.

The wooded hills above the River Wey were overhung in wet fog, and he drove most of the way home from the college in second gear, with the side-lamps on. When at last he steered his old Vauxhall into Morlan Lane, he tossed his cigarette out the window and shifted down to first gear, and he lifted his foot from the accelerator as the front corner of his white bungalow came dimly into view.

When he had first got the job as assistant lecturer back in 1953, he had rented a room right in Weybridge, and he remembered now bicycling back to the old landlady’s house after classes in those long-ago late afternoons, from old habit favoring alleys too narrow for motor vehicles and watching for unfamiliar vans parked or driving past on the birch-shaded lanes—tensing at any absence of birdcalls in the trees, coasting close by the old red-iron V.R. postbox and darting a glance at it to look for any hasty scratches around the keyhole—and alert too for any agitation among the dogs in the yards he passed, especially if their barking should ever be simultaneous with a gust of wind or several humans shouting at once.

The old, old saying had been: Look to dogs, camels don’t react— though of course there had been no camels in Weybridge anyway.

There had still then been periods when he couldn’t sleep well or keep food down, and during those weeks when he was both too jumpy and too quickly tired to pedal the bicycle, he would generally walk home, kicking a stone along ahead of himself and using the opportunity to scan the macadam for skid-marks, or—somehow not implausible-seeming on those particular afternoons—for a stray bowed metal clip carelessly dropped after having had cartridges stripped off it into the box magazine of a rifle, or for the peel-off filter-cover from a gas mask, or for any bits of military-looking cellulose packaging or wire insulation… or even, though he had never actually let this image form in his mind and it would have been hard to see anyway on the black tarmac, for circles scorched into the pavement, circles ranging in size from as tiny as a pinhead to yards across. Sometimes on clear evenings he would simply hurry right past the house and on to the public house by the Bersham road, and come back hours later when the sky was safely overcast or he was temporarily too drunk to worry.

In ’56, with the aid of one last shaky Education Authority grant, he had finally got his long-delayed B. Litt. from Magdalen College, Oxford and been promoted to full lecturer status here, and soon after that he had begun paying on this house in the hills on the north side of the University College of Weybridge. By that time he had finally stopped bothering about—“had outgrown,” he would have said—all those cautious vigilances that he remembered the wartime American OSS officers referring to as “dry-cleaning.”

And he had felt, if anything, bleakly virtuous in abandoning the old souvenir reflexes; fully eight years earlier C himself, which had been white-haired Stuart Menzies then, had summoned Hale to the “arcana,” the fabled fourth-floor office at Broadway Buildings by St. James’s Park, and though the old man had clearly not known much about what Hale’s postwar work in the Middle East had been, nor the real story about the recent secret disaster in eastern Turkey, his pallid old face had been kindly when he’d told the twenty-six-year-old Hale to make a new life for himself in the private sector. You were reading English at an Oxford college before we recruited you, C had said. Go back to that, pick up your life from that point, and forget the backstage world, the way you would forget any other illogical nightmare. You’ll receive another year’s pay through Drummond’s in Admiralty Arch, and with attested wartime work in the Foreign Office you should have no difficulties getting an education grant. In the end, for all of us, “Dulce et decorum est pro patria vanescere.”

Sweet and fitting it is to vanish for the fatherland. Well, better than die, certainly, as the original Horace verse had it. Hale had known enough by then to be sure that he had effectively vanished from the ken of even the highest levels at Broadway, and all but one of the ministers in Whitehall, long before that final interview with C.

So what dormant, obsolete short-circuit was this, that was still occasionally using the old codes as if to summon him? No one had made any kind of contact with him in Green Park on that day in the winter of ’52, and he was sure that no one would be there today, on this second day of 1963. The whole fugitive Special Operations Executive had finally been closed down for good in ’48, and he assumed that all the surviving personnel had been cashed out and swept under the rug, as he had been.

Here’s a list, he thought bitterly as he stepped on the clutch and touched the brake pedal: Walsingham’s Elizabethan secret service, Richelieu’s Cabinet Noir, the Russian Oprichnina, the SOE—that’s four, speak up! They’re all just footnotes in history. Probably there’s an unconsidered routine at the present-day SIS headquarters to call agents of all the defunct wartime services and recite to them an uncomprehended old code, once every ten years. He recalled hearing of a temporary wartime petrol-storage tank in Kent that had been wired to ring a certain Army telephone number whenever its fuel level was too low; somehow the old circuitry had come on again during the 1950s, long after the tank itself had been dismantled, and had begun once a month calling the old number, which had by that time been assigned to some London physician. Doubtless this was the same sort of mix-up. Probably SIS had telephoned the old lady’s boardinghouse in Weybridge before trying the college exchange.

Still, do bring a raincoat.

He had stopped the car in the narrow street now, half a dozen yards short of his gravel driveway and partly concealed from the house by the boughs of a dense pine tree on the next-door property. Of course the only cars parked at the curbs were a Hillman and a Morris that belonged to his neighbors. From here he couldn’t see the bowed drawing room windows, but the recessed front door certainly didn’t give any obvious sign of having been forced since he’d locked it early this morning, and the driveway gravel didn’t look any different; even the cleaning woman wasn’t due until Friday.

The television antenna on the shingled roof swayed faintly in the wind against the gray sky… and now, for the first time, it reminded him of the ranked herringbone short-wave antennae on the high roof of the old Broadway Buildings headquarters of the SIS, and on the roof of the Soviet Embassy in Kensington Gardens, and then even of the makeshift antenna he had at one time and another furtively strung out the gabled windows of a succession of top-floor rooms in occupied Paris…

Et bloody cetera, he thought savagely, trying not to think of the last night of 1941.

In the old SOE code, raincoat had meant “violated-cover procedures,” and until the false-alarm summons ten years ago he had never heard it used in a domestic context.

There was a gun in the house, though he’d have to dig through a trunk nowadays to find it: a .45 revolver that he’d modified according to Captain Fairbairn’s advice, with the hammer-spur and the trigger guard and all but two inches of the barrel sawn off, and deep grooves cut into the wooden grips so that his fingers would always hold the gun the same way. It wasn’t a gun for competition accuracy, but Captain Fairbairn had pointed out that most “shooting affrays” occurred at distances of less than four yards.

But it wouldn’t be of much use across the expansive lawns of Green Park. And according to violated-cover procedures, he must consider himself blown here; his address was even printed in the telephone directory. Play by the old rules, he told himself with a shaky sigh, if only in respectful memory of the old Great Game.

He could get along without an actual raincoat, and he had at least ten pounds in his notecase.

He relaxed the pressure of his foot on the brake pedal and let the Vauxhall roll back down the street until he was able to turn it around in a neighbor’s driveway, and then he shifted rapidly up through the gears as he drove off toward the road that would take him to the A316 and, in an hour or so, to some tube station not too far from the old Green Park in London.

Only three days earlier he had been out in his lifeless garden hanging blocks of suet on strings from the bare oak limbs. The stuff stayed hard in the winter air, and the wild thrushes that would have worms to eat come spring were able to sustain themselves on this butcher shop provender until those sunnier days arrived. He was absently whistling “There’ll Be Bluebirds Over the White Cliffs of Dover” now as he drove, and he tried to estimate how long those suet blocks would last, before new ones would have to be hung; not all the way until spring, he thought fretfully. But surely whatever happened he would be back long before then.

His restless gaze was jumping from the windscreen to the driving mirrors and back, and with a chill he realized that he was once again, after a hiatus of about seven years, reflexively watching the vehicles around him, and noting sections of the shoulder where he could leave the road if he should have to.

It took Hale nearly half an hour to amble around the margin of Green Park this time, through the mist under the dripping oak and sycamore branches, and when at length he slanted for the second time past the gazebo by Queen’s Walk, the old man in the overcoat and homburg hat was still there, still leaning against the rail. Without ever looking directly at the man, Hale passed within fifty yards of him and then strode away across the wet grass toward the benches that lined the north-south path.

His heart was pounding, even as he told himself that the old man was probably just some Whitehall sub-secretary taking a morning break; and when he groped in his pocket for cigarettes and matches, he crumpled the pages of test questions he had thrust there a little less than two hours ago. That was his real world now, the Milton classes and the survey of the Romantic poets, not… the dusty alleys around the embassy in Al-Kuwait, not the black Bedu tents in the dunes of the Hassa desert, not jeeps in the Ahora Gorge below Mount Ararat… he killed the thought. As he shook a cigarette out of the pack and struck a match to it, he blinked in the chilly damp breeze and squinted around at the lawns. The grass in the park was mowed these days, and he doubted that sheep were ever pastured here anymore, as he recalled that they had been right after the war. He puffed the cigarette alight and nodded calmly as he exhaled a plume of smoke.

He had driven no farther into the city this morning than West Kensington and had parked the car in the visitors’ lot of Western Hospital across the rail line from the Brompton Cemetery, then conscientiously trudged up a sidewalk against oncoming one-way traffic to the West Brompton tube station.

When he had been uselessly summoned in ’52, he had got off the Piccadilly Line at Hyde Park Corner, and before walking away up Knightsbridge he had nervously traced a back-tracking counter-clockwise saunter among the splashing galoshes and headlamp beams and drifting snow flurries by the Wellington Arch, frequently peering down at the skirt hems and trouser cuffs of the otherwise interchangeable figures in overcoats and scarves that passed him, and trying to remember the one-man-pace evasion rhythms he had learned in Paris more than a decade earlier.

* * *

This morning he had ridden the underground train right past the park and got off at Piccadilly Circus, and climbed the tube station stairs to a gray sky that threatened only rain.

And he had known he should start straightaway down Piccadilly toward the park, being careful once or twice to glance into shop windows he passed and then double back to them after a few paces, as if reconsidering some bit of merchandise, and note peripherally any figure that hesitated behind him, and after a few blocks to enter a shop and stuff his coat into a bag and re-comb his unruly blond hair and then leave with some group of men dressed in white shirts and ties, as he was, and if possible get right onto a bus or into a cab; but he had not been on foot in Piccadilly Circus since the war, and for several minutes after stepping away from the station stairs he had just stood on the pavement in front of Swan & Edgar and stared past the old Eros fountain at the Gordon’s gin advertisements and the big Guinness clock on the London Pavilion, which was apparently a cinema now; he remembered when it had been occupied by the Ministry of Food, and housewives had gone in there to learn the uses of the new national flour. And for the first time in years he remembered buying an orange from a Soviet recruiter on the steps of the Eros fountain in the autumn of ’41. At last he had stirred himself, though his walk down the wide boulevard, past the columned portico of the old Piccadilly Hotel and then the caviar displays in the windows of Fortnum’s, had been slowed more by nostalgia than by watchful “dry-cleaning.”

I’ll give it an hour, he thought now as he puffed on the cigarette and stared at the top stories of new buildings above the bare tree branches; then an early lunch at Kempinski’s if it’s still there off Regent Street, and after that the long trip home. To hell with the fallbacks. Forget the backstage world, as you were ordered to. Dulce et decorum est.

But he looked behind him, and for a moment all memory of the busy concerns of these last fourteen years fell away from him like a block of snow falling away from the iron gutters of a hard old house.

Though still far off, the man from the gazebo was walking in his direction at a leisurely pace across the grass, glancing north and south with no appearance of urgency. And the pale face under the hat brim was much older now, wrinkled and hollowed with probably seventy years, but Hale had encountered him at enough points during his life to remember him continuously all the way back—to the summer of 1929, when Hale had been seven years old.

Andrew Hale had grown up in the Cotswold village of Chipping Campden, seventy-five miles northwest of London, in a steep-roofed stone house that he and his mother had shared with her elderly father. Andrew had slept in an ornate old shuttered box bed because at night his mother and grandfather had had to carry their lamps through his room to get to theirs, and on many evenings he would slide the oak shutters closed from outside the bed and then sneak to the head of the stairs to listen to the stilted, formal quarreling of the two adults in the parlor below.

Andrew and his mother had been Roman Catholics, but his grandfather had been a censorious low-church Anglican, and the boy had heard a lot of heated discussions about popes and indulgences and the Virgin Mary, punctuated by thumps when his grandfather would pound his fist on the enormous old family Bible and exclaim, “Show it to me in the Word of God!”—and well before he was seven years old he had gathered that his mother had once been a missionary Catholic nun who had got pregnant in the Middle East and left her order, and had returned to England when her illegitimate son was two years old. The villagers always said that it was penitential Papist fasting that made Andrew’s mother so thin and asthmatic and cross, and young Andrew had not ever had any close friends in Chipping Campden. He had known that in the opinion of his neighbors his father had been a corrupt priest of one species or another, but his mother had made it clear to the boy when he was very young that she would not say anything at all about the man.

Andrew’s grandfather had restrained himself from debating religion with the boy, but the old man had taken an active hand in Andrew’s upbringing. The old man always said that Andrew was too thin—“looks like bloody Percy Perishing Shelley”—and was forever forcing on him health-concoctions like Plasmon concentrated milk protein, which all by itself was supposed to contain every element required to keep body and soul together, and Parrish’s Chemical Food, a nasty red syrup that had to be drunk through a straw to avoid blackening the teeth.

Andrew had frequently escaped to hike the couple of miles to the windy Edge-of-the-Wold, the crest of the steep escarpment that marked the western boundary of the Cotswolds, below which on clear days he could see the roofs of Evesham on the plain and the remote glitter of the River Isbourne. In his daydreams his father was a missionary priest, and Andrew tried to imagine where the man might be, and how they might one day meet.

Before retracing his steps across the hills and stubbled fields to the straw-colored stone houses of Chipping Campden he would sometimes follow the old cowpaths south to look, always from a respectful distance, at the Broadway Tower. Actually it was two mottled limestone towers, with a tall narrow castle-keep wedged corner-on between, and the vertical window slits and the high, crenellated turrets gave it a medieval look that had not been dispelled when he’d learned that it had been built as recently as 1800. Years later, when he had gone to do wartime work for the Secret Intelligence Service in London, the SIS headquarters had been in Broadway Buildings off St. James’s Park, and known simply as Broadway; and not until his assignment to Berlin in 1945 had the London offices entirely lost for him the storybook associations with this isolated castle on the Edge-of-the-Wold.

The houses and shops along High Street in Chipping Campden were all narrow and crowded up against one another, the rows of pointed rooftops denting the sky like the teeth of a saw. Though when Sunday morning skies were clear Andrew and his mother would take her father’s little 10-horsepower Austin to the Catholic church in Stow-on-the-Wold, in threatening weather his mother would give in to her father’s demand that they attend the Anglican church in town, and Andrew would hurry along the High Street sidewalk to keep up with the longer strides of his mother and grandfather; the houses weren’t set back at all from the sidewalk pavement, so that if Andrew turned his head away from the street, he’d be peering through leaded glass straight into someone’s front parlor, and he had always worried that the old man’s flailing walking stick would break a window. Andrew had wished he could walk down the middle of the street, or walk entirely away, straight out across the unbounded fields.

On Easter, Andrew and his mother would attend midnight Easter Vigil Mass in Stow-on-the-Wold, and then after they had driven back home, before the little car’s motor had cooled off, all three of them would climb into the vehicle and drive to the dawn service at the Anglican church in Fairford. Little Andrew would sit yawning and uneasy through the non-Catholic and therefore heretical service, sometimes peering fearfully at the medieval stained-glass western window, where a huge Satan was depicted devouring unhappy-looking little naked sinners; Satan’s body was covered with silver scales, and his round torso was a grimacing, pop-eyed face, but it was the figure’s profiled head that howled in the boy’s dreams—it was the round-eyed head of a voracious fish, almost imbecilic in its inhuman ferocity.

Many years later he would wonder if he really had, as he seemed to remember, heard in a childhood nightmare a voice call out to this figure, O Fish, are you constant to the old covenant?—and then a chorus of the voices of the damned: Return, and we return; keep faith, and so will we … And he would suppose that he might have, if the dream had been on the very last night of some year.

Andrew had formally renounced Satan by proxy and been baptized in the actual Jordan River, according to his mother—“on the Palestine shore, at Allenby Bridge near Jericho,” she would occasionally add, very quietly—and when he was seven years old he had taken his first Holy Communion at the church in Stow-on-the-Wold. After the Mass, instead of driving back up to Chipping Campden, his mother had for once driven away from the church heading farther south. Explaining to the boy only that he needed to meet his godfather, she had piloted the little car straight on through Oxford and on, eventually, to the A103 into London. Andrew had sat quietly beside her in his new coat and tie, trying to comprehend the fact that he had just consumed the body and blood of Christ, and wondering why he had never heard of this god father until this day.

In 1929 the Secret Intelligence Service headquarters was on the top floor and rooftop of a residential building across the street from the War Office, in Whitehall Court. When Andrew and his mother stepped off the lift on the seventh floor, they were in the building’s eastern turret; through a narrow window the boy could see some formal gardens in sunlight below, and Hungerford Bridge spanning the broad steely face of the Thames beyond. The lift had smelled of latakia tobacco and hair oil, and the warm air in the turret room was spicy with the vanilla scent of very old paper.

Andrew didn’t know what place this was, and from the frown on his mother’s thin face as she glanced around at the paneled chamber he guessed that she had never been here and had expected something grander.

The man who stepped forward and took her arm had been in his late thirties then, his raven-black hair combed straight back from his high forehead, his jawline still firm above the stiff white collar and the knot of his Old Etonian tie. “Miss Hale,” he said, smiling; and then he glanced down at Andrew and added, “And this must be… the son.”

“Who has no knowledge that would put him at peril,” Andrew’s mother said.

“Easier to do than undo,” the man said cheerfully, apparently agreeing with her. “My dears, C wants you shown right in to him,” he went on, turning toward the narrowest, steepest stairway Andrew had ever seen, “so if you’ll let me lead you through the maze…”

But first Andrew’s mother crouched beside him, the hem of her linen dress sweeping the scuffed wood floor, and she licked her fingers and pushed back the boy’s unruly blond hair. “These are the people who got us home from Cairo,” she said quietly, “when… Herod … was looking for you. And they’re the King’s men. They deserve our obedience.”

“Herod!” laughed their escort as Andrew’s mother straightened and led the boy by the hand toward the stairs. “Well, Herod is no longer in the service of the Raj—and he’s doing any harrying of Nazrani children in Jidda nowadays, for an Arab king.”

Hale’s mother snapped, “ Uskut!”—an exclamation she sometimes used around the house to convey shut up. “God blacken his face!”

“Inshallah bukra,” the man answered, in what might have been Arabic. He and Andrew’s mother nearly had to shuffle sideways to climb the tight-curving counterclockwise stairs, ducking their heads around a caged and buzzing electric light, though Andrew was able to tap up the stairs comfortably.

Andrew was excited by the air of secret knowledge implicit in this place and this man, and he was impressed that his mother had had dealings with whoever these mysterious King’s men were; still, he didn’t like the cruel sort of humor that seemed to be expressed in the lines under the black-haired man’s eyes, and he wondered why these stairs had evidently been built to keep very big men from ascending.

Their escort stopped at a door on the first landing and pulled a ring of keys from his trouser pocket, and when he had unlocked it and pushed it open Andrew was startled at the sudden sunlight and fresh river-scented air. An iron pedestrian bridge stretched away for twenty feet over the rooftop to a rambling structure that looked to Andrew like a half-collapsed crazy old ship, patched together out of a dozen mis-matched vessels and grounded on this roof by some calamitously high tide. Partly the structure was green-painted wood, partly bare corrugated metal; Marconi radio masts and wind-socks and the spinning cups of anemometers bristled on its topsides, and interrupted patterns of round windows, and several balconies like railed decks, implied stairs and irregularly arranged floors within. From various brick and iron and concrete chimneys, yellow and black smokes curled away into the blue sky.

The three of them strode clattering across the bridge, and Andrew watched his mother’s graying brown hair toss in the wind. Got us home from Cairo, he thought; when Herod was looking for you. And the man she called Herod is with an Arab king now, in a place called something like jitter.

Andrew’s mother had instructed him in geography, as well as mathematics and Latin and Greek and history and literature and the tenets of the Catholic faith, but except for the Holy Land she had always dealt cursorily with the Middle East.

At the open doorway on the far side of the bridge two men stood back to let the trio pass, and Andrew saw what he guessed was the steel-and-polished-wood butt of a revolver under the coat of one of them. His mind was whirling with potent words: Cairo and revolver and the Raj and the body and blood of Christ, and he wondered anxiously if it was a sin to vomit after taking Communion. He did almost feel seasick.

The black-haired man now led Andrew and his mother through a succession of doors and narrow climbing and descending hallways, and if Andrew had known where north was when he had come in, he would not have known it any longer; the floor was sometimes carpeted, sometimes bare wood or tile. Then they turned left into a dim side-hall, and immediately right under a low arch, and scuffed their way up another electrically illuminated staircase, this one turning clockwise. Net zero, Andrew thought dizzily.

At the top was a door upholstered quilt-fashion in polished red leather, with a green light glowing above it. Their guide pressed a button beside the door frame, and by this time Andrew wouldn’t have been very surprised if a trapdoor had opened under them, sending them to their destination down a slide; but the door simply swung open.

The black-haired man swept a hand into the little room beyond. “Our Chief,” he said. Andrew was the first to step inside, his nose wrinkling involuntarily at the mingled smells of curry, oiled metal, and a cluster of purple foxglove flowers that stood in a vase on the big Victorian desk.

A stocky man in the uniform of a British colonel was standing beside the room’s one small window, and he appeared to be trying to disassemble a spiderweb with a brass letter opener. Without stepping away from the window he turned toward his visitors; he was bald, with bristly gray hair above his ears, and his weathered jaw and nose were prominent like granite outcroppings on a cliff face. After a moment his chilly gray eyes narrowed in a smile, and he held out his free right hand. “Andrew, I think,” he said.

“Yes, sir,” said the boy, crossing the old Oriental carpet to shake the man’s callused hand.

“Splendid.” The old man returned his attention to the spiderweb then, and Andrew watched him expectantly, soon noticing that the loose left thigh of the old man’s uniform trousers, though clean and pressed, was riddled with little half-inch cuts; but after half a minute had passed Andrew let his eyes dart around the dim room. Six black Bakelite hook-and-candlestick telephones hung on extendable scissors-supports against the wall, and several glass flagons half-filled with colored liquids stood on a table beside them; one wall was all shelves, and models of submarines and airplanes served as haphazard bookends and dividers for the vast collection of leather-bound volumes and sheaves of paper that were crowded together and stacked every-which-way on the shelves. On the walls were hung rubber gas masks, tacked-up maps, diagrams of radio vacuum valves, and a photograph of a group of European villagers lined up against a wall facing a Prussian firing squad.

“There’s a fly here,” said the Chief, without looking up from his work.

Not sure who was being addressed, Andrew glanced back at his mother, who just widened her eyes in helpless puzzlement. Even the man who had led them here was simply blank-faced.

“Andrew, lad,” the Chief went on impatiently, “look here. Do you see this fly, in the web? Waving his legs like a madman.”

Andrew stepped up beside the burly old man and pushed back a lock of his long blond hair to peer at the windowsill. A bluebottle fly was struggling in the spiderweb. “Yes, sir.”

“Can you kill it?”

Bewildered, assuming this was some token sort of test of ruthlessness, the boy swallowed against his nausea and then nodded and held out his hand for the letter opener.

“No,” said the Chief impatiently, “with your will alone. Can you kill the fly just by looking at it?”

Andrew really didn’t know whether he wanted to laugh or start crying. He heard his mother shift and mutter behind him. “No, sir,” he said hoarsely.

The old Chief sighed, and turned to stare for several seconds straight into the boy’s eyes. “No,” he said at last, gently. Then he hugely startled Andrew by stabbing the letter opener into his own left thigh, which gave out a knock that let the boy know it was a wooden leg. Through ringing ears Andrew heard the Chief go on, “No, I see you could not—and good for you. Are you interested in radio, lad?” He rocked the letter opener out of his leg and tested the point with his thumb.

Chipping Campden had only got electricity the year before. “We don’t own one,” Andrew answered. He had fainted in church once, and the remembered rainbow glitter of unconsciousness was crowding in now from the edges of his vision—so he abruptly sat down cross-legged on the carpet and took several deep breaths. “Excuse me,” he said. “I’ll be all right—”

Andrew’s mother was crouching beside him, her hand on his forehead. “The boy hasn’t eaten since midnight,” she said in an accusing or pleading voice.

“Good Lord,” came the Chief’s voice from over Andrew’s head. “Where did they drive from, Scotland? I thought you said they live in Oxfordshire.”

“That’s right, sir,” the black-haired man said, “in the Cotswolds. This is some Catholic fast, I believe.”

“Of course. Polarized, you see? Like Merlin in the old stories, christened. Nevertheless—Andrew.”

Andrew looked up into the old man’s stern face, and he felt clear-headed enough now to get back up onto his feet. “Yes, sir,” he said when he was standing again. His mother had stood up too, and he could feel that she was right behind him.

“Remember your dreams.” The Chief scowled. “Dreams, right? Things you see when you’re asleep, things you hear? Don’t write them down, but remember them. One day Theodora will ask you about them.”

“Yes, sir. I will, sir.” Andrew was simply postponing the effort of trying to imagine some no doubt frightening-looking woman named Theodora interrogating him about his dreams at some future date.

“Good lad. When is your birthday?”

“January the sixth, sir.”

“And why the hell shouldn’t it be, eh? Sorry. Good. Your mother has done very well in these seven years. Do as she tells you.” He waved his hand, suddenly looking very tired. “Go and get something to eat now, and then go home to your Cotswolds. And don’t— worry, about anything, understand? You’re on our rolls.”

“Yes, sir. Uh—thank you, sir.”

Andrew and his mother had been abruptly led out then, and the black-haired man had taken them down to a narrow dark lunchroom or employees’ bar on the seventh floor, and simply left them there, after telling them that their meal would be paid for by the Crown. Andrew managed to get down a ham sandwich and a glass of ginger beer, and he had guessed that he shouldn’t talk about the affairs of this place while he was still in it. Even on the drive home, though, his mother had parried his questions with evasions, and assurances that he’d be told everything one day, and that she didn’t know very much about it all herself; and when he had finally asked which of those men had been his godfather, she had hesitated.

“The man who led us in,” she’d said finally, “was the one who… well, the wooden-legged chap—you saw that it was an artificial limb, didn’t you, that he stabbed himself in?—he took the…” Then she had sighed, not taking her eyes off the already shadow-streaked road that led toward Oxford and eventually, beyond that, home. “Well, it’s the whole service, really, I suppose.”

On our rolls.

Shortly after the visit to London his mother had begun receiving checks from an obscure City bank called Drummond’s. They had not been accompanied by any invoices or memoranda, and she had let her father believe that the money was belated payment from Andrew’s delinquent father, but Andrew had known that it was from “the Crown”—and sometimes when he’d been alone on the windy hill below the Broadway Tower he had tried to imagine what sort of services it might prove to be payment for.

Remember your dreams.

In his dreams, especially right at the end of the year and during the first nights of 1930, he sometimes found himself standing alone in a desert by moonlight; and always the whole landscape had been spinning, silently, while he tried to measure the angle of the horizon with some kind of swiveling telescope on a tripod. Once in the dream he had looked up, and been awakened in a jolt of vertigo by the sight of the stars spinning too. For a few minutes after he woke from these dreams he couldn’t think in words, only in moods and images of desert vistas he had never seen; and though he knew—as if it were something exotic!—that he was a human being living in this house, sometimes he wasn’t sure whether he was the old grandfather, or the ex-nun mother, or the little boy who slept in the wooden box.

He always felt that he should go to Confession after having one of these dreams, though he never did; he was sure that if he could somehow manage to convey to the priest the true nature of these dreams, which he didn’t even know himself, the priest would excommunicate him and call for an exorcist.

And he had begun to get unsolicited subscriptions to magazines about amateur radio and wireless telegraphy. He tried to read them but wasn’t able to make much sense of all the talk of enameled wire, loose couplers, regenerative receivers, and Brandes phones; he would have canceled the subscriptions if he had not remembered the one-legged old man’s question— Are you interested in radio, lad?—and anyway the subscriptions had not followed him to his new address when he went away to school two years later.

In her new affluence Andrew’s mother had enrolled him in St. John’s, a Catholic boys’ boarding school in old Windsor, across the Thames and four miles downriver from Eton. The school was a massive old three-story brick building at the end of a birch-lined driveway, and he slept in one of a row of thirty curtained cubicles that crowded both sides of a long hallway on the third floor—no hardship to someone used to sleeping in an eighteenth-century box bed—and ate in the refectory hall downstairs with an army of boys ranging from his own age, nine, up to fourteen. To his own surprise, he had not suffered at all from homesickness. The teachers were all Jesuit priests, and every day started with a brief Mass in the chapel and ended with evening prayers; and in the busy hours between he found that he was good at French and geometry, subjects his mother had not been able to teach him, and that he could make friends.

Obedient to his mother, he had told his new companions about his youth in the Cotswolds but had not ever mentioned the circumstances of his birth, and never told them about his peculiar corporate “godfather.”

His mother had motored down to visit on three or four weekends in each term, and had written infrequent letters; her invariable topics of discussion had been the petty doings of her neighbors and an anxious insistence that Andrew pay attention to his religious instruction, and politics—she had been a Tory at least since Andrew had been born, and though glad of the failure of MacDonald’s Labour Party in ’31, she’d been alarmed by the subsequent general mood in favor of the League of Nations and worldwide disarmament: “Not all the beasts that were kept out of the Ark had the decency to perish,” she had said once. Andrew had known better than to try to introduce topics like his father, or the mysterious King’s men in the rooftop building in London. In the summers Andrew had taken the train home to Chipping Campden, but he had spent most of his time during those months hiking or reading, guiltily looking forward to the beginning of the fall term.

In the spring of 1935 one of the Jesuit priests had come to Andrew’s cubicle before Mass to tell him that his mother had died the day before, of a sudden stroke.

Andrew Hale let the dapper old man in the homburg hat walk on past him at a distance of a dozen yards, while Hale squinted through his cigarette smoke and scanned the misty lawns back in the direction of the gazebo and Queen’s Walk. The only people visible in that direction were a woman walking a dog in the middle distance and two bearded young men beyond her striding briskly from north to south; neither party was in a position to signal the other, and they were all looking elsewhere in this moment of the old man’s closest approach to Hale; clearly the old man wasn’t being followed. And neither was Hale, or the old man would have seen it and simply disappeared, to try to meet later at a fallback.

Now the old man had halted and pulled a map from an inside pocket. Hale’s eye was caught by the flash of white paper when the man partly unfolded the map and began frowning at it and glancing at the distant roofs of buildings. In fact the building on top of which Hale had first met him was only a ten minutes’ walk to the east, past St. James’s Park and Whitehall, but Hale knew that this flashing of the map was a signal; and so Hale was looking directly at him when the old man caught his gaze and then raised his white eyebrows under the hat brim.

Hale took one last deep draw off the cigarette, and tossed it away onto the grass, before walking over to where the man stood. His heart was still thumping rapidly.

“Lost, Jimmie?” he said through exhaled smoke, with muted sarcasm.

“Without a clue, my dear.” Jimmie Theodora folded up the map and tucked it back inside his overcoat. “Actually,” he went on as he began strolling away in the direction of Whitehall, with Hale following, “I do hardly know where I am in London these days. The Green Park I remember has a barrage balloon moored back there by the Arch, and piles of help-yourself coal lining the walks. You remember.”

“No beatniks, in those days.” “

Aren’t they frightful? Makes you wonder why we still bother.”

“You—we?—are still bothering, I gather.”

“Yes,” Jimmie Theodora said flatly. “And yes, you had bloody well better say ‘we.’ ”

It’s “we” when you say it is, Hale thought as he followed the old man across the wet grass, not sure whether his thought was wry or bitter.

The day of his mother’s funeral in Stow-on-the-Wold had dawned sunny, but like many such Cotswold days it had turned rainy by noon, and the sparse knot of mourners on the grass by the grave had been clustered under gleaming black umbrellas. They were shopkeepers and neighbors from Chipping Campden, mostly friends of Andrew’s grandfather—but the solemn, frightened boy had glimpsed a face at the back of the group that he was sure he recognized from his First Communion day trip to London, six years previous. Andrew had tugged his hand free of his grandfather’s to go reeling away from the grave toward the black-haired man, who at that moment seemed like closer kin than the grandfather; but Andrew had caught a surprised and admonishing scowl on that well-remembered face, and then the black-haired man had simply been gone, not present at all. Later Andrew had concluded that the man must have stepped back out of sight and quickly assumed a disguise—false moustache? cheek inserts, contrary posture, a sexton’s dirty work-shirt under the quickly discarded morning coat and dickey?—but on that morning Andrew had gone blundering through the mourners, tearfully and idiotically calling, “Sir? Sir?” since he hadn’t even known the man’s name. Jimmie Theodora had no doubt been embarrassed for him and made an unobtrusive exit as soon as possible.

The priests at St. John’s had known the name and address of a solicitor Andrew’s mother had been in touch with, which proved to be a pear-shaped little man by the name of Corliss, and after the funeral ser vice the solicitor had driven Andrew and his grandfather to an office in Cirencester. There Corliss had explained that the uncle—he had paused before the word and then pronounced it so clearly and deliberately that even Andrew’s grandfather had not bothered to object that no such person existed—who had been paying for Andrew’s support and schooling would continue to do so, but that this benefactor would now no longer be persuaded that an expensive and Roman Catholic school like St. John’s was appropriate. Andrew’s grandfather had shifted to a more comfortable position in his chair at that, clearly pleased. Andrew was to be sent to the City of London School for Boys instead, and would incidentally be required to add the study of German to his curriculum.

During the long drive back south to Windsor, where Andrew could at least finish out the present school term at St. John’s, his grandfather had gruffly advised the thirteen-year-old boy to get into the Officers’ Training Corps as soon as he could; war with Germany was inevitable, the old man had said, now that Hitler was Chancellor, and even the blindly optimistic Prime Minister Baldwin had admitted that the German Air Force was better than the British. But Andrew’s grandfather had been an old soldier, having fought with Kitchener in the Sudan and in South Africa during the Boer War, and Andrew had not taken seriously the old man’s apocalyptic predictions of bombs falling on London. Andrew’s only goal at this period, which he had known better than to confide to the elderly Anglican hunched over the steering wheel to his right, had been a vague intention to become a Jesuit priest himself one day.

Within a year that frail ambition had been forgotten.

In those days the City of London School had been housed in a four-storied red-brick building with a grandly pilastered front, on the Victoria Embankment right next to Blackfriars Bridge and the new Unilever House with all its marble statues standing between the pillars along the fifth-floor colonnade; and it was only a short walk to the Law Courts at the Temple, where barristers in wigs and gowns could be seen hurrying through the arched gray stone halls, and to the new Daily Express Building in Fleet Street, already known as the Black Lubyanka because of its black-glass-and-chrome Art Deco architecture. Like the other boys at the school, Andrew wore a black coat and striped trousers and affected an air of sophistication, and his aim now was to become a barrister or a foreign correspondent for some prestigious newspaper.

The older boys, enviably allowed to use the school’s Embankment entrance and to have lunch out in the City, had all seemed to be very worldly and political. Some, captivated by newsreels of the splendid Olympic Games in Berlin as much as for any other reason, subscribed to Germany Today and favored the pro-German position of the Prince of Wales, who had become King Edward VIII in early 1936. Others were passionate about Marxism and the valiant Trotskyite Republicans fighting a losing war against the fascist rebels in Spain. It had all seemed very remote to Andrew, and he had tended to be tepidly convinced by whatever argument had most recently been brought to bear. Any decision about his grandfather’s advice had been taken out of his hands when all the boys at the City of London School had been drafted into the Officers’ Training Corps, and so Andrew had twice a week put on his little khaki uniform and got into a bus to go to a rifle range and obediently shoot at targets with an old .303 rifle loaded with .22 rounds; the idea of an actual war, though, was still as exotically implausible as marriage—or death.

But Edward VIII abdicated in order to marry an American divorcée, and the Russians and the Germans made a pact not to attack each other, and Parliament passed a law declaring that men of twenty years of age were to be conscripted into the armed forces. And in September of 1939 the newspapers announced that Germany had invaded Poland and that England had declared war on Germany, and all the boys were evacuated to Haslemere College in Surrey, forty miles southwest of London.

For an uneventful eight months Andrew lived with two other boys in a cottage that got so cold in the winter that the chamber-pot and its contents froze, and went to makeshift classes in the now-very-crowded Haslemere College buildings; then in May of 1940 the German Army finally moved again, sweeping through Holland and Belgium, and Prime Minister Chamberlain’s government collapsed, to be replaced by Churchill’s National Government; and in September the bombs began to fall on London.

TWO

London, World War II

The game is so large that one sees but a little at a time.

—Rudyard Kipling, Kim