9,37 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Sonicbond Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: On Track

- Sprache: Englisch

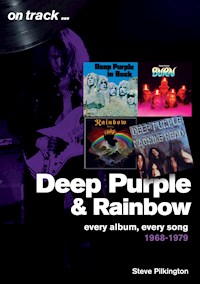

Few would deny that Deep Purple were one of the most influential and popular heavy rock bands to emerge from the melting pot of the late 1960s. They went through several line-up changes, and stylistic shifts, before splitting up for the first time in the mid 1970s. Talismanic guitarist Ritchie Blackmore carried the spirit on when he formed Rainbow after leaving Purple in 1975, particularly through his partnership with legendary singer Ronnie James Dio. Deep Purple reformed some years later, of course, but many consider this original, sometimes turbulent, decade to be their most significant.

Steve Pilkington puts his focus on the period from Shades Of Deep Purple in 1968 through to the first dissolution of the band after Come Taste The Band in 1976, via such classics as Machine Head and In Rock. He also discusses first four Rainbow studio albums, including the classic Rainbow Rising and the hit-laden Down To Earth album in 1979, taking a look at every song from every album in detail. He also discusses live recordings plus DVD and video releases. The result is the most exhaustive guide to the band’s music yet produced, as critical opinion rubs shoulders with facts, trivia and anecdotes to provide a fascinating ‘alternative history’ of these revered bands. Whether you are a hardcore fan or simply want a guide through the world which lies beyond 'Smoke On The Water', this book is for you.

The Author: Steve Pilkington is a music journalist, proof-reader and broadcaster. He is Editor in Chief for the Classic Rock Society magazine Rock Society, and contributes to other publications such as Prog. Before taking on this work full-time, he spent years writing for fanzines and an Internet music review site on a part-time basis. He has recently published “Black Sabbath – Song By Song” (Fonthill, 2018) book, and has written the official biography of legendary guitarist Gordon Giltrap. In addition, he presents a weekly progressive rock radio show titled ‘A Saucerful of Prog’ on Firebrand Radio. He lives in St.Helens, Merseyside.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 280

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Sonicbond Publishing Limited

www.sonicbondpublishing.co.uk

Email: [email protected]

First Published in the United Kingdom2018

First Published in the United States 2019

Reprinted 2020

This digital edition 2022

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data:

A Catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Copyright Steve Pilkington 2018

ISBN 978-1-78952-002-6

The rights of Steve Pilkington to be identified as the authors of this work have been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from Sonicbond Publishing Limited

Printed and bound in England

Graphic design and typesetting: www.fullmoonmedia.co.uk

Also by Steve Pilkington:

Black Sabbath - Song By Song

(Fonthill, 2017)

Perilous Journey: The authorised Gordon Giltrap biography

(Wymer Publishing, 2018)

Acknowledgements

I would firstly like to thank those band members who gave their time for interviews with me for the Classic Rock Society, which have been very useful in putting this book together: Glenn Hughes, David Coverdale, Roger Glover, Ritchie Blackmore.

Thanks to Stephen Lambe, for commissioning and faith, Jerry Bloom for massive Purple knowledge, Janet for patience and dog-wrangling, and all of those people who have done research before me!

Huge thanks to Doug Currie, Steve Richardson and Par Holmgren

for photo contributions.

Finally thanks to all at the Classic Rock Society for the last ten years, without whom I wouldn’t be who or where I am today (am I anywhere?).

And, of course, everyone who has passed through the ranks of Deep Purple and Rainbow: the founders of the feast...

Contents

Introduction

Shades Of Deep Purple

The Book Of Taliesyn

Deep Purple

Concerto For Group And Orchestra

Deep Purple In Rock

Fireball

Machine Head

Made In Japan

Who Do We Think We Are

Burn

Stormbringer

Rainbow Rising

On Stage

Long Live Rock ‘n’ Roll

Down To Earth

Roundup – Odds, Sods, Live and Video

Epilogue – What Came Next

Afterword – The Ultimate Playlist

Bibliography

Introduction

The seeds of what would become Deep Purple were sown in 1967, when Middlesex-based guitarist Ritchie Blackmore and Leicester-born keyboard player Jon Lord joined forces with ex-Searchers drummer Chris Curtis, with a view to forming a band. Curtis had the idea of a band without a fixed line-up, whereby members could come in and out, and the project was thus christened ‘Roundabout’. Almost immediately, the idea was thrown off course by the withdrawal of the erratic Curtis, and Lord and Blackmore set about getting the band on track themselves. The initial line-up was completed by bassist Nick Simper, who had been playing with Lord in a band called the Flower Pot Men, and temporary drummer Bobby Woodman. Vocalist Rod Evans was brought in after being spotted fronting a band called The Maze, whose drummer, Nottingham-born Ian Paice, came along with Evans, replacing the dissatisfied Woodman. Soon afterward, in early 1968, the band renamed themselves Deep Purple, and played their first UK show at The Lion pub in Warrington, Cheshire.

This first incarnation of the band lasted for a mere 18 months, though managing to record three albums in that time. In summer 1969, Evans and Simper were replaced by vocalist Ian Gillan and bassist Roger Glover, both from a band named Episode Six. This line-up quickly established themselves with a heavier rock direction, and became the most well-known line-up in most people’s eyes. After a run of successful albums, inter-band feuding resulted in the departure of both Gillan and Glover in 1973, and the band were back to square one. Around this time the pattern of naming the Purple line-ups as ‘Marks’ (Deep Purple Mk I, Mk II, Mk III etc) became established. Unique among their contemporaries, it is unclear where this identification system originated, but it has been suggested that the first appearance was on a 1973 double compilation album called Deep Purple Mk I And II, which featured a disc dedicated to each line-up’s output. Whatever the truth of the matter. The Mk III line-up needed to be finalised.

First into the fold was Staffordshire native Glenn Hughes, bassist / vocalist with Trapeze, who had achieved some success with the three albums he had played on. Quickly joining Hughes was ‘unknown boutique salesman from Redcar’ David Coverdale, who had, in something of a fairy-tale story, been plucked from obscurity after being persuaded to send in a demo tape. The band quickly got into the studio and recorded the acclaimed Burn album, and were an immediately successful rebuttal to the critics. The next album, Stormbringer, however, saw the band bringing in an overt funk/soul influence – primarily from Hughes – which led to the departure of the disenchanted Blackmore in 1975. Replacing him was American ‘wunderkind’ Tommy Bolin, who had turned heads with his time in the James Gang and with Billy Cobham, and the revitalised band recorded the excellent Come Taste The Band album. Alas, the hoped-for rebirth failed to materialise, with Bolin’s soon-to-be apparent heroin problem seriously blunting his effectiveness on the road, and the band imploded inside a year, after a March 1976 show in Liverpool.

While Purple went on hiatus until a surprising reunion in 1984 (outside the scope of this book), Ritchie Blackmore immediately set about keeping the flame burning, forming Rainbow in 1975, using most of the band Elf as his initial backing band, including singer Ronnie James Dio. Rainbow recorded three stunningly successful albums with Dio as frontman until his departure in 1978 led to the introduction of the Hawaiian-shirted, cropped-haired Graham Bonnet as his unlikely successor. After Bonnet’s sole Rainbow album, 1979’s Down To Earth, this book leaves the story, but suffice it to say that Rainbow continued for a while until Purple abruptly reconvened, while Coverdale went on to enormous success with Whitesnake. For many, though, that first decade was where the true legends were forged, and thus it is that period that we will explore in these pages...

Shades Of Deep Purple

Personnel:

Rod Evans: vocals

Ritchie Blackmore: guitars

Jon Lord: keyboards

Nick Simper: bass guitar

Ian Paice: drums and percussion

Record Label: Parlophone (UK), Tetragrammaton (US)

Recorded May 1968, produced by Derek Lawrence.

UK release date: September 1968. US release date: July 1968.

Highest chart places: UK: Did not chart, USA: 24

Running time: 43:27

Album facts

The album was recorded in May 1968, after the band returned from a Scandinavian tour under the name Roundabout. They changed their name to Deep Purple on the suggestion of Ritchie Blackmore, whose grandmother was reportedly very keen on the song of the same name – an easy-listening staple dating back to the 1930s. They completed the recording in a mere three days at Pye Studios in London, with production duties handled by Derek Lawrence, who went on to great success – with his stint as the man behind the production desk for the first three Wishbone Ash albums of particular note. The album gained immediate traction in the United States, largely on the back of the success of first single ‘Hush’, but by contrast went largely unheralded in their native UK, where it was only finally granted a release in the September of that year. The US record label was Tetragrammaton, whose intriguing name refers to the four letter Hebrew biblical name of God, from which the words Yahweh and Jehovah are derived. The label was co-owned by the comedian Bill Cosby. In the UK, the album came out on the Parlophone label, the EMI subsidiary which had released the early Beatles work.

Containing a roughly equal mix of covers and original material, the album is an enjoyable yet tentative musical step. Unlike the debut releases of Led Zeppelin or Black Sabbath, which would offer fully realised blueprints for their musical direction, Shades Of Deep Purple showed a band taking the first move in the direction which they would perfect some time later. In this regard, their early work mirrors that of Yes, for example, whose first two albums likewise saw them hinting, albeit extremely well, at the template they would go on to make their own.

Album Cover

The album cover photograph is fairly typical of the time, with the band appearing rather stiffly in fashionable outfits purchased for them at the notable London boutique the ‘Mr Fish Emporium’, where they did the photo shoot. Incidentally, and possibly of coincidental naming, the owner and fashion designer Michael Fish was the man behind the infamous ‘kipper tie’! The same shot was used for both the American and British covers, but in different formats; while the US version had the shot repeated several times in squares on the front cover, both colour and monochrome, the UK release went for a much simpler design, with the one big shot for the whole cover, against a purple background (naturally) with the title above. The band name was omitted from the UK cover, whereas in the American design it was highlighted in a different colour in order to emphasise it.

‘And The Address’ (Blackmore, Lord)

The first track on the album was also the first piece written by Blackmore and Lord – before the group had formed around them, in fact – and also the first track to be recorded on the initial day in the studio (Hey Joe, Hush and Help were the others to be completed on that first day). Interestingly, and somewhat amusingly, Nick Simper has claimed (in an interview with Purple devotee and author Jerry Bloom) that the unusual title comes from an exclamation made ‘after a gentleman had broken wind’ (‘...and the address...’), but this is unsubstantiated. An instrumental, it is in fact an extremely effective way to kick off the album, with a minute or so of free-form organ fading in gradually only to give way to a series of dramatic power chords introducing Blackmore’s guitar carrying the melody. The sound is very much of its time, in a slightly psychedelic, ‘proto-prog’ way, but moves along at an energetic tempo, introducing Lord and Blackmore as the clear musical leaders via some fairly impressive soloing. The track was used to open all of their shows up until the release of the next album, but was somewhat disappointingly dropped thereafter. Deep Purple had made their presence felt, though it would take some time for their homeland to join the party...

‘Hush’ (South)

It is quite an unusual phenomenon for a cover version to effectively launch a band’s career single-handedly, not to mention defining them, in the American market at least, for some time, but Hush did that in spectacular fashion for Deep Purple. Released as a single in July 1968, it reached number 4 in the US chart and number 2 in Canada, despite making barely a ripple in the UK. The success of the single more or less dragged the album up with it to become a sizeable American hit (peaking at 24), and to this day there are many fans in the US who cite this first line-up as their favourite Purple era. The track was originally written by Joe South – based partly on a traditional Gospel song – and first recorded by Billy Joe Royal in 1967, for whom it became a minor hit. The Purple recording follows the arrangement of the Royal version quite faithfully, although much more dramatically. Opening with a slightly incongruous crashing intro, it gives way to Lord’s churning, funky organ underpinning Blackmore’s fiery lead lines. Evans delivers the song well, though it is somewhat amusing to hear this Eton-born, very English singer delivering the line ‘I can’t eat, y’all, and I can’t sleep’! A hilarious promo film was made of the band clearly debunking the whole lip-synching culture as they looned about in an open air poolside location, complete with large open fire. Evans sings alternately in swimming trunks and towel and lounging in a deckchair, while Lord, clad in black leather trenchcoat, attacks such ‘instruments’ as garden furniture and a fishing net, with which he rescues a stricken Evans from the pool. Simper, meanwhile, temporarily abandons his bass to run around with a tiny wheelbarrow. Showing an early example of the band’s oft-demonstrated sense of humour, it is well worth seeking out online.

‘One More Rainy Day’ (Lord, Evans)

An original composition by Lord and Evans, and the B-Side of the ‘Hush’ single, this was the final song to be recorded for the album, on the third day in the studio. Opening with the sound of thundery weather (taken from a BBC sound effects record, as were all of the similar bridging elements between songs on the album), Lord’s organ leads us into the song in strident fashion, but it soon settles into a pleasant if unremarkable song, treading the slightly psychedelic pop road which was infested with identikit would-be pop stars in those late-‘60s days. It’s a mildly diverting song to listen to, but far from a classic – and certainly a long way from being representative of where Purple would travel later.

‘Prelude: Happiness / I’m So Glad’ (Blackmore, Evans, Lord, Paice, Simper / James)

A two-part piece here, as the band preface a cover of the Skip James song ‘I’m So Glad’, popularised by Cream shortly beforehand, with an instrumental introduction of their own. Titled ‘Prelude: Happiness’, and taking up almost three minutes of the seven and a half minute track, this is actually the more interesting section of the medley by some distance. Clearly the brainchild of Lord – despite the somewhat unlikely credit to all five members, including Evans – it is a dextrous keyboard-led workout, incorporating themes from the Rimsky-Korsakov work Scheherazade. Indeed, it proves something of an anti-climax when the band transition into a somewhat uninspired arrangement of ‘I’m So Glad’. Once again, there is some nice organ work from Lord, and brief flashes from Blackmore, but it becomes very repetitive, with Evans’ decidedly non-joyful intonation not helping matters. Clearly, the band already had some aptitude for stretching themselves beyond conventional ‘pop’ songwriting limits, and an extended version of the prelude would arguably have constituted a stronger track. In fact,’ I’m So Glad’ was suggested by Evans and Paice, who had played it in their previous band The Maze, but the timing of the recording so soon after Cream’s version brought it into the public eye made it appear somewhat unimaginative.

‘Mandrake Root’ (Blackmore, Lord, Evans)

The opening track on the second side of the album is another which was intended to be an instrumental, but rather than have two instrumental tracks on the album, along with ‘Prelude: Happiness’, some cursory (and mildly suggestive) lyrics were added by Evans before the recording. The track takes its name from the hallucinatory plant, which was said to scream when pulled from the ground, but it is more directly taken from the name of a band which Blackmore was in the process of forming prior to the Roundabout offer coming his way. The origin of the song is somewhat controversial, as there are two schools of thought as to its writing. Officially, it was written by Blackmore and Lord around the time of the band’s formation, but there were claims by a man named Bill Parkinson, a guitarist who had played, like Blackmore, in The Savages, that the track was taken directly from a piece he wrote called ‘Lost Soul’. It was later rumoured that the band had settled with him for a fairly modest sum. However, the other version of events is that Blackmore wrote the piece heavily influenced by Jimi Hendrix, which is backed up by the fact that the main riff bears a strong resemblance to the latter’s hit ‘Foxy Lady’. Whatever the truth of the matter, it was a strong piece, and a natural vehicle for soloing, which was borne out by its long life in the Purple set as a lengthy springboard for improvisation. Unquestionably the track which showcases the band’s instrumental prowess and virtuoso soloing ability most obviously on the album (Lord and Blackmore are backed up by Paice’s frenzied drumming to produce an aural chaos similar to the live freak-outs Pink Floyd were doing at the time), nevertheless the studio version’s six-minute duration was still only the starting point, with live versions regularly lasting for well over 20 minutes.

‘Help’ (Lennon, McCartney)

Back to the cover versions again here, for this imaginative adaptation of the Beatles classic. Owing a lot to the template laid down by Vanilla Fudge – an early favourite of the band – the song is slowed down to a virtual crawl, with every ounce of drama wrung out of it in Evans’ impassioned vocal. In truth, this is a very creditable and effective rendition, not least because it follows the brief which John Lennon had in mind when he wrote the song; as he has gone on record as saying that he wrote it as a slow song, but that the tempo was sped up significantly in order to make it more commercial. In that sense, the Purple version can be seen as the first attempt to perform the song in the way that it was intended, and indeed it does bring out the desperate sentiment in the lyric more than the much lighter Beatles recording. Without doubt one of the strongest tracks on the album, and one for which Evans’ smooth, ‘crooner’ type voice was actually ideally suited.

‘Love Help Me’ (Blackmore, Evans)

This Blackmore / Evans composition is another fairly unremarkable original song, beginning with more of those slightly tiresome sound effects before a grandiose set of power chords introduce the band playing with some energy and aggression, but unfortunately not all that much in the way of substance. There are some ill-advised vocal harmony sections which call to mind a half-hearted Beach Boys track, while Evans himself tries manfully but fails to stamp his authority on the vocal. Blackmore solos all over the cut, seemingly trying to lift it above the mundane but, again, it is far from his best work. Interestingly, he uses the wah-wah pedal extensively on the track – something he would do only occasionally for the band going forward – and it doesn’t really suit his style, as he sounds like a man trying a little too hard. Probably the weakest track on the album, it showed that the band were yet to properly develop their compositional abilities.

‘Hey Joe’ (Roberts)

Another fairly unimaginative choice of cover, given the success that Hendrix had enjoyed with the song and also the fact that groups up and down the country were including the song as a regular in their live sets at the time. Still, the arrangement is interesting, without a doubt. The lengthy introduction illustrates Lord’s classical influence again, as the band ‘borrow’ liberally from ‘The Miller’s Dance’, from the 1919 ballet The Three Cornered Hat, by Spanish composer Manuel de Falla. This is set against a staccato rhythm strikingly similar to that which would make an appearance a couple of years down the road on ‘Child In Time’, and it takes until almost two and a half minutes in for the song proper to begin. At just over four minutes in, Lord’s strident organ ushers in a reprise of the opening section before Blackmore comes in with a guitar solo which, though excellent, is very reminiscent of the classic Hendrix rendition. After another verse and chorus, another small helping of that ‘Child In Time’ rhythm pattern sets us up for a big, album-closing, series of power chords, which are followed by the somewhat incongruous sound of footsteps and a door closing. It’s an entertaining seven minutes for sure, and closes the album quite strongly, but in the final analysis less than half of the duration has any connection with the original song – which was written by US songwriter Billy Roberts in 1972, although on early pressings it was mistakenly credited to the members of Purple themselves. Poor old Manuel de Falla never got a look in, of course!

Related Song

‘Shadows’ (Lord, Evans, Simper, Blackmore)

When the band recorded the demo tape which led to the album, the only track thus recorded which failed to make the cut for the final album was this one – and it’s something of a shame as the song does have promise. Driven along by a strident, marching verse riff, it has the ability to lodge in the listener’s brain after only a single listen, and is pleasingly infectious. The chorus, with a melody not entirely dissimilar to the Monkees’ ‘Daydream Believer’, is less riveting, but it’s brief, and we’re soon back that great propulsive main riff once again. Blackmore again uses the wah-wah here, but in more successful fashion than on ‘Love Help Me’, and the guitar work is more confident and fluid overall than that track. It certainly could be argued that the inclusion of ‘Shadows’ could well have strengthened the album overall, but at least it finally surfaced some decades later as a bonus track on a CD re-release of the album.

The Book Of Taliesyn

Personnel:

Rod Evans: vocals

Ritchie Blackmore: guitars

Jon Lord: keyboards

Nick Simper: bass guitar

Ian Paice: drums and percussion

Record Label: Harvest (UK), Tetragrammaton (US)

Recorded August and October 1968, produced by Derek Lawrence.

UK release date: June 1969. US release date: October 1968.

Highest chart places: UK: Did not chart, USA: 54

Running time: 43:57

Album facts

Appearing an astonishing three months after the debut in America, where it was rushed out to capitalise on an Autumn tour, the album was held over a significant length of time in the UK, eventually getting a release in June 1969, when the band were doing a tour of their home country. Absurdly, by this time, the band had recorded AND released their third album in the US, and were already toying with line-up changes. Recorded at De Lane Lea studios in London, the UK release was, notably, the first album put out on EMI’s new ‘progressive’ Harvest label, but it still failed to trouble the chart compilers in any way, as opposed to the US where is hit a rather modest 54. The title of the album is something of an oddity, coming from the 14th century Welsh manuscript The Book of Taliesin, but altering the spelling of the final word. The sleeve notes to the original US release of the album continue this quasi-mystical approach, referencing a bard of King Arthur’s court, Taliesyn, as a spiritual guide, taking the listener on an exploration of the band’s personalities and souls. All of which is fairly hard to stack up against a cover of ‘River Deep Mountain High’, it has to be said.

Album cover

The cover artwork was a big progression from the debut, as band and record company seemed to grasp the value of appealing to the new ‘hippy’ audience. Carnaby Street suits and bouffant hairdos were no longer the way to go, and the brief this time was to go much further out on a limb. The cover was a gatefold, for a start, with suitably de rigeur fantasy artwork by future university professor, John Vernon Lord. In fact, this was the only album cover that he ever worked on, as he moved into teaching and book illustration shortly thereafter, but he recalls getting a brief to produce something with an ‘Arthurian / fantasy touch’, and to illustrate the title and band members’ names by hand (indeed, the latter appear somewhat incongruously adorning the side of what resembles some kind of hot air balloon). The album title and band name actually appear three times within the painting, in a progressively smaller size, where they battle for space with assorted castles, minstrels, chess pieces and various animals. It is quite eccentric to say the least, but oddly fascinating. The remainder of the cover – rear and inner gatefold – was disappointingly earthbound in nature, with monochrome photos of the band abounding, and with the unbearably pretentious sleeve notes being replaced in the UK by a photo of the band around a grand piano.

‘Listen, Learn, Read On’ (Blackmore, Evans, Lord, Paice)

Credited to the full band minus Simper, and cut from very much the same cloth as ‘And The Address’ from the debut album, this proggy-psychedelic piece is in some respects a sort of ‘unofficial title track’, as it contains the chorus line ‘You’ve got to turn the pages, read the Book Of Taliesyn’. In fact, the song takes its inspiration from the cover painting as, contained within its lyrics, are references to such elements of that design as the hare, the chessmen, the minstrels, the castles and even, indirectly, the fish (via the unlikely line ‘I shall be of more service to thee than three hundred salmon’)! The outstanding contributor here is without a doubt Ian Paice, whose frantic drumming keeps the track in top gear and instils a sense of urgency which keeps it just the right side of ridicule – which is no mean feat, given the way Evans solemnly intones the verses in heavily echoed spoken-word fashion as if delivering words of great import and power. Away from this somewhat absurd affectation, and as Paice thrashes away, Blackmore steps up to deliver a heavily distorted solo which is far from his best, both in tone and execution. It’s an enjoyably over-the-top romp in its way, but it does give the impression that the album is going to be some sort of conceptual affair, with this as its ‘overture’ of sorts, as it climaxes with the line ‘...and what hereafter will occur’. Sadly that was not to be the case, as what did occur immediately thereafter was an instrumental followed by a distinctly non-mystical Neil Diamond cover...

‘Wring That Neck’ (Blackmore, Lord, Simper, Paice)

Another instrumental here, credited to the band except for Evans, and one which proved to be a regular in the band’s set for years to come. Beginning with Lord’s opening salvo (sounding oddly like the Woody Woodpecker laugh I might add), followed by some massively booming drum beats, this track fairly rips along from start to finish, with only a short, unaccompanied Blackmore part at around four minutes to throw the returning theme into dramatically sharpened relief. Lord is on top form here, while Blackmore appears to have his heart in things much more than on the opening track – indeed, his solo gives the biggest pointer thus far to his signature style which would be developed over the coming years. The title, of course, could just as easily refer to the neck of a guitar as to any act of violence, but this did not stop Warners in America getting decidedly cold feet about it, and it was renamed as the seemingly random ‘Hard Road’ on early US pressings. The track would go on to carve another small niche in the world of rock trivia not too far in the future, which we will look at when discussing Deep Purple In Rock, in 1970...

‘Kentucky Woman’ (Diamond)

Once again we see a cover version making its way onto the record (the first of three, in fact), though given the fact that the album was recorded only three months after the debut we should perhaps not be surprised that original material might have been a little thin on the ground at the time. On this occasion, it is a song from the somewhat unlikely pen of Neil Diamond, though it is certainly one of his more upbeat compositions. The Purple version retains the vocal melody and the basis of the song, but takes it in a rockier direction, away from the acoustic-based arrangement on Diamond’s 1967 original. It’s entertaining but for the most part unremarkable, with Blackmore again sounding as if he is soloing in his sleep, with only Lord’s typically-wild keyboard solo taking the excitement level up a notch. It’s a more complete arrangement than the original for sure, but the area where it falls badly short is in Evans’ vocal, which is delivered without any semblance of the soul which oozes from the Neil Diamond version, and another sign that the band really did need someone stronger fronting them. The track was released as a single, in slightly edited form, but did not chart as high as ‘Hush’ in the States. In the UK, of course, it sank without trace. The B-Side was ‘Wring That Neck’, which one imagines must have come as a shock to some of the pop-oriented teens who purchased the single!

‘Exposition / We Can Work It Out’ (Blackmore, Simper, Lord, Paice / Lennon, McCartney)

Yes, it’s that ‘cover version’ trail again, with the Beatles the target for the second album on the run, but this is in the two-part style of ‘I’m So Glad’ from the debut album, as the somewhat pretentiously titled opening instrumental ‘Exposition’ runs to almost three of the seven minutes here. Once again the classically-trained Lord is raiding his bag of orchestral influences, this time with Beethoven (an obvious rearrangement of part of his Seventh Symphony) and Tchaikovsky (a lesser, but still present, bit of Romeo And Juliet) being the ‘borrowings’ of choice. It’s still a very entertaining and superbly played introduction, but a little nod to those great composers alongside the names of the Purple members (minus Evans again) would have been a nice admission. Interestingly, it seems odd that Lord gets so little recognition for his ‘rocking the classics’ on these early albums, while his keyboard contemporary Keith Emerson would be celebrated for doing very much the same thing at very much the same time. The Beatles section of the track is far less interesting, being driven by Blackmore’s insistent guitar licks throughout, trying another bit of the old Vanilla Fudge trick by slowing down the mid-section, but generally ending up as one of the less remarkable Beatles interpretations of the ‘60s. It’s certainly nowhere near as impressive or inventive as ‘Help’, with Evans once again sounding as if he is reading the weather forecast rather than pouring out his soul to his partner as they try to salvage their relationship.

‘Shield’ (Blackmore, Evans, Lord)

Opening the second side of the vinyl, this Blackmore / Evans / Lord original is just about as trippy as Deep Purple ever got. Opening with an insistent bass figure, it settles into a mellow groove similar to Cream’s more psychedelic moments, and underpinned by some mantra-like percussion from Paice, particularly during the guitar solo which takes us into the ‘acid rock’ realm typical of the times. Blackmore is clearly out of his comfort zone, but he manages to sprinkle some magic over proceedings as the track gently marinates in a stew of rippling piano and insistent bass. The lyrics are steeped in mystical imagery involving children playing on a green hill, fathers smoking ‘the pipe of a better life’ and the hoped-for protection of a nebulous shield of some sort. It probably symbolises the desire to cling to a safe, harmonious family life, but it works well in its fantastical finery when put together with the music.

‘Anthem’ (Lord, Evans)

A rare Lord / Evans composition is up next, in the shape of the stately ballad ‘Anthem’. Evans’ lyric is a fairly standard take on the old ‘guy misses girl, finds the night time the hardest’ template, but it’s quite well written for what it is, and on this occasion he evokes some emotion in his delivery, as Lord’s beautiful melody is clearly the perfect vehicle for his voice. The vocal harmonies in the chorus threaten to over-egg the pudding somewhat, but it is, for all that, a very good song. Where it takes off to another level, however, comes after three minutes or so when the instrumental section kicks in. Lord’s solo organ passage brings things right down, before being accompanied by his own sensitively arranged string quartet. Blackmore is next to enter the fray with a delicate guitar solo, which is made fascinating when you realise he is playing in the exact style of a violin soloing over a quartet, yet with a pick. Very, very clever. The band come back in at that point to usher in a further Blackmore solo passage over the fuller sound, bringing an almost tangible sense of relief after the deliberately restrained preceding section. Evans returns to deliver the final verse and chorus before the song comes to an end, with that lengthy instrumental section standing as a minor masterclass of subtlety and arrangement skill. Along with ‘Wring That Neck’, certainly the outstanding piece on the album. Notably, due to its complexity and string arrangement, this was one of two songs from the album never played live (the other being ‘Exposition / We Can Work It Out’).

‘River Deep Mountain High’ (Barry, Greenwich, Spector)

Well, what can we say, as we reach the end of the album with a ten minute version of the Ike And Tina Turner classic? Well, we could certainly say things like ‘overblown’ and ‘filler’, but let’s take a look at the track. Firstly, of course, it isn’t ten minutes of ‘River Deep Mountain High’ at all, but another example of the lengthy unrelated intro so beloved of the band, and Lord in particular, on this album. This time out, there isn’t even a separately titled opening, with band writing credits, despite the fact that the song itself doesn’t enter proceedings until four and a half minutes in, and even then the next 40 seconds or so are taken up by Evans’ slow, solemn intoning of the first two lines of the song, like a sort of ‘60s hipster monk. So, by the time they get going, half of the track is the titular song itself. It’s hard to see why the intro is left without separate credit, although it may be simply because there is very, very little in the way of an actual tune buried in there. Instead, the band flail around for four and a half minutes like a fly unable to find a surface on which to settle, with Lord up to his classical borrowing antics again as he is unable to resist slipping in a little Also Sprach Zarathustra in there. This is not wholly unsurprising as it had been made rather popular by its use in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey