8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

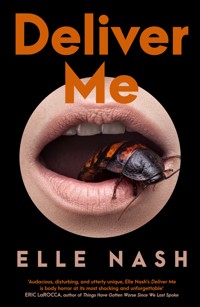

- Herausgeber: Verve Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

** Longlisted for the Saltire Society Fiction Book of the Year 2024 **

From the author of Nudes and Animals Eat Each Other comes an unsettling story of motherhood, manipulation and murder.

At a meatpacking facility in Missouri, Dee-Dee and her coworkers kill and butcher 40,000 chickens in a single shift.

The work is repetitive and brutal, with each stab and cut a punishment to her hands and joints, but Dee-Dee's more concerned with what is happening inside her body. After a series of devastating miscarriages, Dee-Dee has found herself pregnant, and she is determined to carry this child to term.

Dee-Dee fled the Pentecostal church years ago, but judgment follows her in the form of regular calls from her mother, whose raspy voice urges her to quit living in sin and marry her boyfriend, Daddy, an underemployed ex-con with an insect fetish. With a child on the way, at long last Dee-Dee can bask in her mother and boyfriend's newfound attention. She will matter. She will be loved. She will be complete.

When her charismatic friend Sloane reappears after a twenty-year absence, feeding her insecurities and awakening suppressed desires, Dee-Dee fears she will go back to living in the shadows. Neither another miscarriage nor Sloane's own pregnancy deters her: she must prepare for the baby's arrival.

PRAISE FOR DELIVER ME

'Nash takes no prisoners in this visceral slice of body horror that mixes up pregnancy, poverty and Pentecostalism. It's a hot mess of a novel coolly rendered. Which just makes the horror of it cut even deeper' - HERALD

'A horror with heart' - DAZED

'To read the work of Elle Nash is to be restored to faith in the wildness, wetness, and visceral power of contemporary American fiction. Deliver Me is a barbed liturgy of bugs, babies, meat, the gospel, women lusting women, women lusting men, and the human body. Get saved' - MELISSA BRODER, author of Death Valley & Death Valley

'Depraved and brilliant and I love it so much!' - JANE FLETT, author of Freakslaw

'Audacious, disturbing, and utterly unique, Elle Nash's Deliver Me is body horror at its most shocking and unforgettable' - ERIC LaROCCA, author of Everything the Darkness Eats

'Brilliant, fearless, and utterly deranged, Deliver Me is a gift to readers who love a seriously unhinged woman... A wild, disturbing, super-smart novel, Deliver Me is unforgettable' - CHELSEA G SUMMERS, author of A Certain Hunger

'Elle Nash dances a knife's edge in Deliver Me, a world where a person's hands can save or steal, conceal or reveal, lure you in or lie, and sometimes all of these at once' - SARAH GERARD, author of True Love

'Elle Nash is one of the best writers alive. This book is utterly fearless, utterly devastating, and an uncompromising masterpiece. Reading Deliver Me made me feel like I was possessed' - JULIET ESCORIA, author of Juliet the Maniac

'Deliver Me is pure jaw-dropping horror while also serving up a piercing insight into the control of women's bodies and the expectations placed upon them... Nash's ending is one you will never forget' - STYLIST

'In Deliver Me, Nash has produced a singular, devastating, uncompromising masterpiece' - GLASGOW REVIEW OF BOOKS

'A gruesome body horror... I read it in two days flat... The squeamish need not apply - the braver of you should tuck in' - SPECTATOR

This novel contains discussion of miscarriage and depictions of animal cruelty and body horror.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Praise for Deliver Me

‘Audacious, disturbing, and utterly unique… body horror at its most shocking and unforgettable’ – ERIC LaROCCA, author of Everything the Darkness Eats

‘An uncompromising masterpiece. Reading Deliver Me made me feel like I was possessed’ – JULIET ESCORIA, author of Juliet the Maniac

‘Brilliant, fearless, and utterly deranged’ – CHELSEA G. SUMMERS, author of A Certain Hunger

‘No one can swirl sex and strange quite like Elle Nash, and Deliver Me rubs creation against devastation on a wild ride of self discovery away from a Christian-shaped cult… A work of art from an artist to watch’ – BRIAN ALAN CARR, author of Opioid, Indiana

‘Nash dances a knife’s edge in Deliver Me, a world where a person’s hands can save or steal, conceal or reveal, lure you in or lie, and sometimes all of these at once’ – SARAH GERARD, author of True Love

‘Nash excels at capturing the claustrophobia of rural poverty and religious fundamentalism… Haunting’ – KIRKUS

‘Unsettling… Readers drawn to gritty character studies should take a look’ – PUBLISHERS WEEKLY

‘Deliver Me plays like a feminine version of Southern Gothic… A highly unusual and very creative piece of writing… Strange but beguiling’ – MEDIUM

For L

For B

For Baby and Me

‘O Lord, deliver me from evil men. Preserve me from the violent’

– Psalm 140:1

TLB, 1971

‘The roach and I aspire to a peace that cannot be ours – it’s a peace beyond the size and destiny of the roach and of me’

– Clarice Lispector, The Passion According to G.H.

This novel contains discussion of miscarriage and depictions of animal cruelty and body horror.

First Trimester

XXXX

The factory is a fertile body, each breast a beginning. I make geometry of the meat and that keeps my mind in line – calming, comforting tenders and perfect fingers, my pneumatic scissors make sense of the mess. It’s 3:50 am when I arrive on the floor in my sexless scrub top and Number Five is pissed. I slip on my disposable arm wraps, then tie my plastic apron behind my back. Everything that drops into our section is mostly peach with pale yellow lumps of fat. Thank God there is no blood. When I’m not at work, I remember moving the length of my fingers over each smooth breast, feeling for the catch of bone or a string of tendon against my latex glove. Number Five catches me missing a breast and shouts. I look up, then cut faster to catch up. Trembling flesh flops and tumbles down a conveyer belt at 140 birds or more a minute, and I cut, cut, throw the pieces into wide emerald vats to be sorted. It’s hard to focus, and sanitizer fogs my eye protection. This morning the sky was July clear, and as I walked through the glass doors glittering with dawn light, I knew something was different, couldn’t stop squeezing the skin of my stomach. In the locker room, I pressed my hands deep into my hips, searching for the nubs of my pelvis through the surrounding paunch of my sore, spongy fat.

During first break I swallow back the nausea worming up my throat. I step outside and walk past the rows of parked cars, the sun barely rising and the constellation fading out in the north. Momma calls it the Northern Cross. ‘God is watching over us,’ she would say, but when I moved out and got the internet I looked it up. It’s not a cross but a swan in flight. The air outside is normally swollen with blood and animal waste, but today it smells earthy, like wild grass and fresh milk. The mild country across the highway is peppered with paste-colored double-wides, old barns, twined bundles of hay, our factory nestled neatly between that and a few acres of chicken farms – if you can call them that. Oblong, warehouse-sized huts with thousands of clucking broilers breathing in their shit. We’re the kill station. The biggest poultry supplier to Missouri, Arkansas, and Oklahoma.

When first break is over, workers sort into their sections like marbles rolling toward one uneven end. Number Three shows up next to me.

‘Good morning, Number Four.’

I nod and cover my nose with my paper mask. My hunger prods, and pressure in the muscle of my jaw, below my tongue, makes me salivate. A bloat sits below my belly button, achy and full. I try to remember the last time I bled. Three weeks, maybe. It’s never been regular, sometimes it takes months, but always I’m thinking, She’s here again. Inside me. An alarm rings and the assembly line clunks on, first from the adjacent warehouse rooms, then ours. Air hisses through the hose of my scissors, and I ready the blades by schlicking them open and shut a few times. For the rest of the day I cut and cut and cut.

When I get home, Daddy is on the couch watching a show about women who undergo extreme plastic surgery and spend weeks in a hotel away from family, working with physical trainers to lose weight. Then they’re revealed in their new, authentic forms. These women have never been ugly, the announcer says, they were just hiding their good looks. The plastic surgeries helped them unfold, like teasing open a flower bud. The TV glow catches in the light of Daddy’s whiskey. It’s the bottom-shelf stuff; I can smell the sweetness from where I am. When I lean over and kiss the side of his mouth, the taste of acetone moves into mine. I drift a weak finger down along his pockmarked jawbone and it speed-bumps over the gnarled scar on his cheek.

‘Eaten yet?’ I ask.

‘No,’ he says. ‘Texted Blake, no landscaping work today.’

I scrub my hands and forearms at the kitchen sink and notice an inflamed cut near my thumb. On day one Momma asked if I feared being injured or losing a finger. She lives an hour away on some wooded land alongside a tiny ravine and calls nearly every day. Momma loves to call me, now that she is all alone. A daughter has to listen to her momma. Isn’t that what the Bible says? Honoring your parents. It’s the child who always must be dutiful, responsible, especially now that Momma’s getting frail. And Momma has needs, and she doesn’t want to be alone anymore. Momma wants grandchildren, and I’m the only one who can give them to her. Once I passed into my thirties she began to ask with increasing intensity, ‘When are you going to get married and have children, Dee-Dee?’ I understand, because I want children, too. More than anything, I want a daughter for myself. So I can teach what I have learned, so I have someone to relate to. Someone I can see myself in. I move through most of my days thinking of Momma and pregnancy and of my future daughter, obsessing over the fat at my thighs and waist, which is already large and soft and shapely, willing my torso to grow, grow more. All day my thoughts blunder forward like my momma, my momma, my momma.

If I told Momma about my blessing now she’d repeat my name in her soft, sprawling tongue as if I weren’t already yearning for her approval. Dee-Dee, she’d say, then pause and rewet her lips, until the church bells ring and that rice is raining down on you both, you shouldn’t even think about having a child. It’s not right. Not right now.

Right in the eyes of God, she means. At this point she only has to imply it. Everything in this town and the state of Missouri is about what is right in the eyes of God. It’s so hard to make her happy, and yet I know she’s right, because some assurance from Daddy would make the daily slog of work so much easier. If we were married I would know we were a team, that he was going to take care of me; that someday, the killing would end.

Momma would then cluck her tongue and switch the topic: Has he found a job yet?

At the kitchen sink, I put the sponge’s green side to my skin and scrub the scratch with antibacterial soap. There’s red around a scab of yellow.

‘Did you pay rent?’ I ask Daddy.

He eases back into the couch and shakes his head. ‘We have to kite the check,’ he says. He chews on the inside of his cheek, and the thick scar that twists from his chin to the bed of his eye moves with it. I love its hard pink and trace the scar from bottom to top, as if his entire past were burrowed inside its trail.

‘I’ll ask for overtime,’ I say.

I rip off three paper towels from the roll and pat my wrists dry, but my hands still smell like the caustic stink of sanitizer. I won’t tell Daddy about the baby, not yet. Not until I’m sure. I pick up a can of chili, but the muscles in my hand won’t grip, and it keeps slipping around the can opener. Not much longer, then I can give up the factory.

‘Daddy,’ I say.

He keeps his attention on the TV. A woman in a royal-blue dress stands onstage in front of a screen the size of a building. A shot of her ‘before’ face frowns next to a live feed of her ‘after’ face as she glides down the runway. The ‘before’ face is round, the lips thinner, skin paler and pockmarked, eye bags mooning up as her mouth forms a flat line. The new face flashes veneered teeth so bright they appear blue, tight eyelids, the skin even tighter over her brow bones, all forming a waxy tension that’s pulled a decade from her face.

‘Daddy,’ I say again, ‘I need your help.’

His head turns. Even with the scar, he is the most beautiful man I’ll ever love. I’ve only ever been with one other person.

‘What?’ he says, annoyed. ‘What’s wrong with you?’

I walk into the living room, handing him the can with the opener affixed to it. I don’t say what’s wrong with me. He puts down his drink and takes the can. Daddy twists until the lid cracks in release and hands it back to me. The smell of cold meat permeates the air.

‘Don’t forget to feed the bugs,’ he says, turning back to the show.

‘They’re your bugs,’ I say.

Momma never allowed me to watch TV, and when I see Daddy’s eyes gloss over I understand why. He is gone, lost inside the fantasy of the woman in the sequined dress, who looks into a beveled mirror at her new self. She cries, and a group of people rush the stage to embrace her. A mother and father, a husband, and two children crowd around her and cry, too, as though the woman has just returned from a kidnapping or death. She’s been growing the new, better version of herself this entire time. The children, especially, are sobbing, twisting their faces to play to the camera and to the audience, all of whom stood up to applaud. Their mouths stretch in ecstasy, but you can see in their darting eyes: the kids are just mirroring what they think they’re supposed to feel. This is it, their eyes say. The mother we were meant to have.

1996

Revival season atFaithful Floods Temple of God. Service was usually held in church, a building that was essentially two double-wides attached either way to a circular brick room in the center. When it was revival season we moved to tents in large fields out by the Walmart. In the tent I clasped my hands together, fingers joined into a fist. The stiff cotton of Momma’s dress brushed my arm as she stepped toward the stage, the scent of White Diamonds in her wake. Momma lived for this – she adored a deliverance, attended baptisms as often as sermons, to watch people sprawl on the carpet in tears for Christ.

My father touched her shoulder, and she shot him a look, pulling away. This was before the earth took him back, which is how I see it now. I don’t believe in angels anymore. I always wonder if Momma regrets anything about the way she treated him. Momma doesn’t talk about it. My father glanced at me and resumed clapping to the rhythm of the organ.

We had joined the congregation the first year we moved to Cassville, after my father got out of the army. For him, it was a renewed effort to make community, to please Momma, I’d always thought. Momma had been raised in the faith all her life. She craved the spectacle, like the rest of the congregation. A parishioner weeping and falling to the carpet. What they called ‘the power of Christ’. Wood stretched and popped as half the crowd stood from the antique folding chairs, their slew of hands and fingers stretched toward our sister Sloane onstage. Sloane, Sloane; I pushed my knuckles into my lower lip and pressed hard against my teeth. I don’t know how I hadn’t noticed her before. I was so young then, susceptible to the fears of God that settled inside good people and made them sick.

‘Let’s put hands on our sister,’ the pastor said. His open palms faced the light and the congregation’s did, too, everyone moving closer to the stage. The timbre of his voice was sultry, like a song booming into Sloane’s ears. She dropped to the ground, her shaggy hair set loose against the grass, light blue eyes sharpened by the stage lights. The women crowded around, touching her, praying, brunette victory rolls and floral skirts swaying to the reedy organ music. It was what the pastor wanted: no trousers, skirts only. No makeup, so you didn’t stink of pride. The crowd prayed together until their voices melded into a single rumble while a stray shriek or two punctuated the edges.

My father put his palm on the space between my shoulders and nudged me forward. I walked past the women with their plain hair pulled tight, past the men with sweat beading on their shaved necks. The second I put my hand out, palm up like the pastor’s, Momma grabbed my wrist and pushed it toward the girl.

‘Touch her,’ she hissed. ‘There’s not much time left.’ I placed my palm on her calf. Sloane smelled like stone fruit. Peach-colored flush feathered her cheeks.

The pastor began to speak faster, louder. ‘Your relationship should be with the Living Word,’ he said. ‘Out there are the enemies. They prowl, try to keep us ignorant, control us, keep us from knowing the truth of this world.’

His fingers pressed on her forehead, then pushed her hair back, leaving wet snarls plastered to her skin. Our hands held her in place; Sloane kicked and waved her arms, and a throaty moan rattled from her chest. We locked eyes. Her mouth curled into a smile, and she licked her teeth and winked. I thought I might’ve made it up, created a lie, when in truth she had let me into hers.

I looked back at my father, then to Momma. Both were totally entranced in the moment. Everyone pushed against Sloane, their oily faces hungry for their own taste of her deliverance.

Sloane’s dress had bunched up around her hips, and the pastor held her waist down with his fingertips. Stray hairs glittered on her otherwise smooth knees. I played with the lace of her sock, tufted at her ankle, then released my hand from her leg, but something pushed me back toward her, jarring my head and neck forward, clattering my teeth. The pastor kept chanting, ‘Resist the adversary! There is not much time left!’ I turned to see the pink membrane of Momma’s lips, her red Avon lipstick bleeding into its edges. ‘O the adversary!’ her mouth repeated. ‘Our sister needs your help, O Lord!’ The sea of sweating cheeks, all chanting, ‘Resist! Submit to the Lord!’ The words grew indistinguishable until Sloane closed her eyes and began to shake and snarl. Suddenly our world was normal again, and the lie went on as Sloane shuddered once, twice, then collapsed into the sea of hands.

XXXX

Meat chickens are not bred to make life. The internal mechanisms are all there – ovaries with their tiny clusters of eggs, the hormonal drive – but meat chickens don’t live long enough to lay. They are bred to be eaten. Their breasts and bodies grow at an abnormal rate, tripling in weight in those first few days of life, and are sent to slaughter at five pounds. Each chicken on my line is only fifty days old. Every one must be processed by the end of the day. If even one person calls off work, the rest of us have to pick up the slack; we don’t get to leave until the work is finished.

In each section of the warehouse, a massive digital counter on the wall marks the processing of an entire bird. It counts up red, until we hit our death goal. I use it to keep track of the time. There’s no clock, and we have to keep our watches and phones in our lockers. A buzzer alerts everyone to breaks, lunch, and shift changes. If we manage to process 140 birds per minute, we know we’re near break time when the death counter approaches twenty-six thousand. At fifty thousand, first shift is over and my day is done.

The deboning line comes with the bonus of not having to see the birds die. They begin their journey feathered and writhing, their feet in fork-shaped hangers attached to a long chain. The chain moves behind a steel wall, where the birds’ heads are dipped into a trough of electrified water before they’re reeled to the killing room, where their throats are dragged past an automatic cutter. Then they’re scalded bald, hocked, and beheaded before getting disemboweled and moved to the deboning room. By the time the birds make it to me, they’re so clean they don’t look like anything that’s ever been alive.

Once the line starts, no one talks. For the next four hours, my ears are filled with the whirring of ceiling fans, the spritz of sanitizer, and the slop of flesh into buckets until the lunch buzzer.

I weave through at least a hundred sweaty foreheads lined up for the building’s two toilets to get lunch from my locker. The pneumatic scissors make my palm tingle. I stretch my fingers back to my wrist, pulling out the ache. Daddy is probably waking up, checking his phone for messages or calling around for work. I shoot him a text. Daddy doesn’t text back, and part of me wants his attention so badly I consider telling him right away about the pregnancy. I open my lunch bag and pull out tuna salad on Wonder Bread. My mouth waters as I bite through it, soft on top and soggy in the middle. The tang of mayonnaise and salty flecks of fish separate onto my tongue.

‘How did you find out you were pregnant with me?’ I ask Momma over the phone.

‘Oh’ – she coughs – ‘I knew the instant I conceived you, honey.’ She drags from a cigarette and blows out. ‘I just knew, the way you know when you’ve got a tickle in your throat that you’re about to get sick. With you, there was an ache in my bones. I told your father the day it happened, rest his soul. Why, Dee-Dee? Are you pregnant again? You can’t think this one will succeed. You know you are living in sin and need to redeem yourself to the Lord.’

‘Daddy promised me a ring,’ I say. ‘He’s saving up from his odd jobs.’

‘God judges all sexually immoral people, and that includes you, Dee-Dee.’

My chapped lips stretch into a stinging grimace. She always pushes past me and into God.

‘He wants the ring to be bought with honest money.’

‘The Lord blesses only those with a pure heart,’ Momma says.

I wipe crumbs from my face, from my shirt; place my hand on my abdomen over the new fragility. Then Momma mumbles something I don’t hear. I’m too distracted by thoughts of a pregnancy test and what else I need to buy on the way home.

‘Swollen?’ she asks.

‘What?’

‘Are your hands still swollen? I can hear people in the background. I know you’re at work, honey.’

‘I woke up this morning with my rings cutting off my circulation,’ I say. ‘Had to soak my hand in a bowl of ice water to get them off.’

It’s a lie, but I want her sympathy. I hold my palms out even though she can’t see; they’re red where I’ve been rubbing them.

‘Sometimes aspirin works,’ she says. ‘You know, you should call Sloane soon.’

‘Momma,’ I say.

They’ve kept in touch ever since Sloane moved away years ago. I don’t know why. Probably Momma wanted to pretend she had a daughter who did all the things she liked. Probably her and Sloane did pretend that – that they were family all these years – and they talked about how I wasn’t very good, and how I was dating a criminal now, and how I’d never have a baby because the last five have died inside me. Probably Momma loved to tell Sloane she thought my womb was a coffin and about how I quit going to church, and how proud she was of Sloane for going back to God after all her mistakes. Sloane would have everything I couldn’t: a good husband as hot as a movie star who didn’t care about her teenage pregnancy; maybe she even got to keep it, all while he was funding her stay-at-home life.

‘Sloane doesn’t want to talk to me,’ I say.

Momma tuts. She tsks. She sucks on her cigarette. Momma says, ‘I know she would love to hear from you.’

Every time I think of Sloane I go wet with envy. A gnawing hunger for her life, unnamable, as deep as sex. Sloane and her husband in bed, her nose pressed into his inky hair, the two so close they smell as one. Babies sleeping, soon to wake up and adore them. Scribbly drawings and colored handprints all over the fridge. Sloane for sure would have a life full to bursting. Whenever a girl in the church got married, we’d all gossip about who’d be next and how many months it’d be until the newly married couple announced their pregnancy. Before wedding season, Sunday school teachers had the preteens write letters to their future husbands, encouraging us to imagine being blessed by a man who would bring us closer to God. Some girls kept purity journals where they described all the ways they would serve these men. I prayed that God would surround me with an assortment of devout males laid out like a buffet: short men, tall men, feminine men with slim wrists and long torsos, silky hair, amber eyes. I prayed for jutting pectorals, beefy arms. Religious men to make me right. Rebellious men to make me slick and thirsty. Most of all, virile men. Someone who could make me a woman, give me the chance to grow – to become a doorway for something greater than myself. (‘Before every great doorway is a doormat,’ Sloane loved to say.)

Within months of her wedding, the newlywed girl would become something else. Her skin would ripen; she would glisten. Her arms flushed pink; her hair grew longer, shinier. Her breasts swelled. We’d gossip, write our letters, dream about a man passionate for fucking and following Christ. We’d imagine our bellies inflated, too, hump our pillows at night. Then we’d sign the letters, Yours in Christ, Your Future Wife.

The buzzer rings harsh, and I tell Momma I got to go. Lunch is over. I check my phone once more and Daddy still hasn’t messaged me. Amid the crumple of lunch bags and the scrape of chairs against concrete, I pet the fat beneath my belly button as if it’s a blanket tucking in the multiplying cells – my manic, buoyant new life.

XXXX

Three weeks of pregnancy is too early to tell anyone, even the father. The highest risk of miscarriage exists between four and six weeks of pregnancy, and after that it drops by over fifteen percent. I have researched these numbers countless times because it’s when I lose every baby. By week eight, the rate falls to three percent, and I’ve made it to week eight only once. Pregnancy is a thing that happens, and we have little choice what happens, so we speak of it in passive terms: I’ve been pregnant. Over the last two years I’ve been pregnant five times, and each time a heart the size of the tip of a sharpened pencil thrums inside me as the embryo attempts to cross the threshold into that of a fetus. In Missouri, a fetus is protected life. One time the state prosecuted a woman, an addict, for miscarrying at eight weeks, and she almost went to jail for infanticide. Before the cluster of cells develops eyelids, the buds of toes and fingers, the shape of a human heart, it’s considered a person. But somewhere along the way the heartbeat stops, and before I can get to a doctor, I bleed it out.

That first time I missed my period I bought a test from CVS and the faintest cross bloomed inside the window. Two days later I took another and the line appeared lighter. I shook Daddy awake, waving the uncapped stick in front of his eyes.

‘A baby!’ I said. ‘We’re going to have a baby!’

He turned on the lamp on the nightstand and squinted at the stick. ‘Get that out of my face.’

I grabbed his hands and put them to my cheeks, fever-hot and heavy. The rims of his eyes were a bright, burning pink. ‘I love you,’ I said to him. ‘I love you, I love you.’

He lifted his groggy eyelids and cupped my chin.

‘Our baby will have your wide ears and my upturned nose,’ I said. ‘Its hair will be brown, like mine, or maybe more serious and dark like yours.’

Daddy rolled his eyes, and I traced my fingers down his scar.

‘Don’t fret,’ I said. I went to kiss him, and he turned his face, leaning back into his pillow.

A week before that first ultrasound, desperate meat chickens parted as I shuffled through the hut at work, their clucks and bawks shrill and constant. A ragged, peach-colored crew of them scattered from me, many of them missing feathers, skittering on ghostly feet. I searched for stragglers. Cleaning out the huts meant clearing up the dead or killing the sick ones. The sick were worthless to the factory. I never wanted to kill them. I wiped sweat from my forehead, queasy from the stink, my stomach cramping tighter and tougher. Pregnancy pains. Implantation, or my uterus expanding. Rows of feed funnels and large overhead fans repeated in a dizzying geometric blur from one end of the building to the other. It became hard to breathe. One hen stopped and sat in place as I stumbled through the flock. I dreaded this part. My hands shook. I pressed my stomach with one hand to hold in the pain and picked up the hen with the other, turning her over on her side. The hen’s torso burned hot through my latex glove. The knuckles of her feet showed large, knobby abscesses – signs of infection. I held her legs in one hand and her head in the other. The bird’s small pupil whirred shut, and I broke her neck the way management taught me: grab at the base of its head, pull the neck away from the torso as fast as I could, then slam it down quick to snap the spine. She was gone. I tossed the hen behind me. Her wings flapped on autopilot, a small bowl of dust and shit kicking up, as if she were still alive.

The cramps got worse and I hunched over, holding back tears. A passing coworker locked eyes with me, and the smallest acknowledgment of my discomfort caused the wall to buckle. I burst into tears, which channeled muddy tracks through the dirt on my cheeks. The woman had walked away as I cried, and I wanted to ask her to come back so I could tell her I wasn’t in pain, I wasn’t losing my baby, anything to make it not real, but talking was not a choice. Management was strict with fraternization. It was considered time theft. We weren’t allowed unscheduled bathroom breaks. When my shift was over I hobbled straight to the bathroom, where I removed my disposable jumpsuit and pulled down my underwear to find a dark clot of blood, mucusy and thin like a brown egg yolk. I wiped at it.

Daddy told me the miscarriage was nature’s way of eliminating bad genes. It was retarded, he’d said, or it had extra fingers. Daddy knows a lot about breeding because he breeds exotic insects. Sometimes, Daddy said, Mantodea abandon their young only to find them and eat them alive.

‘Am I diseased?’ I asked. ‘Am I broken?’

‘That’s just nature,’ he’d said, tapping on one of the insect cages in our bedroom.

Momma told me to get a different job. But where was I going to go? I’d applied at Walmart three times, and besides, I didn’t want to drive over an hour to work every day. Momma had no answers. She just asked if I was going to church like I was supposed to be. I spent the whole evening in the tub until the water turned frigid and pink from the remaining tissue leaking from me. I broke into tears, my quiet heaves sending ripples through the water. Daddy didn’t check on me once.

The second through fifth miscarriages were the same: the thin blue line, excitement, and, a few weeks later, crushing disappointment. Blood beneath me, from inside me, the same dark blood.

XXXX

In the family-planning aisle at CVS there’s only condoms and lube. Up and down other aisles are pads and tampons, vaginal washes, shaving cream in pink cans, and expensive razors. Clear plastic bottles full of blue and red pills, turquoise gelcaps, colloidal silver. Cartoon bandages. Not a single pregnancy test. I give up, anxious and a little damp, and grab a Red Pop, Bugles, and a chocolate bar. An associate in a red vest is bent over in the candy aisle, checking inventory.

‘Miss?’ I ask. She straightens up. ‘Where are the pregnancy tests?’

‘Oh,’ she says. ‘Behind the counter. With the cigarettes.’

She pushes her acetate glasses up the bridge of her nose and takes me to the counter, unlocks a glass cabinet behind it.

‘We have the generic kind, which are only two dollars, then there’s the brand-name sticks – here’s one with two in it for eight dollars; here’s an electronic one, that’s fourteen.’

Fourteen dollars could go far.

‘Eight dollars,’ I say. She pulls down the pastel-colored box and scans it with the rest of my items, removing the plastic antitheft sensor. I want her to say something – giddiness branches inside my chest, an itch to share – but she just wipes at the puffy gray skin beneath her eyes.

‘Do you have children?’ I ask. Her eyes flick up at the question.

‘Will that be all?’ she says.

‘Yeah. Thanks.’

When I walk through the front door, tests hidden in my purse, Daddy’s on the couch watching a forensic cop show. Some boomer in sunglasses makes jokes to a younger associate while standing over a corpse.

‘Did you see the new car?’ I ask.

‘Red Volvo?’ Daddy says.

‘Yeah, and it’s parked in my spot. Gotta be a new tenant upstairs.’

‘Where’d you park?’

‘Blake’s spot was the only open one,’ I say. I open the Red Pop with a snap and take a loud sip.

‘He’s gonna shit bricks,’ Daddy says. He reaches his hand out to me; at first I think it’s a sign of affection but quickly realize it’s for the soda.

‘Shit,’ I say. ‘I only got this one for me.’

Daddy lets his arm fall in disappointment. ‘It’s fine,’ he says.

I take it to mean it isn’t fine. It’s hard to discern when Daddy is being truthful and when he isn’t, when he’s joking or serious. Like me and Momma, anxiety underpins our relationship. I fear his leaving me, as though any mistake can end the whole thing. I don’t know for sure where I got this idea, but it showed up one day like a rock in my shoe. I hand him the soda without a word.

‘You gotta move your car,’ Daddy says, and takes a loud sip. ‘I don’t want drama.’

‘I’ll move it after dinner,’ I say.

The husk of our microwaved meal sits by a sink full of dishes. It’s Daddy’s night to wash them, but he’s too absorbed by his TV show. In this scene, police officers are questioning their suspect, a young boy with autism. I sweep up crumbs from the floor and find ants crawling from under the sink toward the fridge. I watch their tiny marching bodies, which look like specks of dirt walking in a neat, thin row. Daddy keeps his special insects in our room: rare cockroaches, a stag beetle, and a massive praying mantis. Sometimes there are more and sometimes less. The room is also filled with dozens of shadowboxes of insects that have passed, insects he’s preserved himself. He’s more meticulous about their care than he is with anything else in the house. If one of them dies, he gets physically upset, ritualistically setting the body on foam with its most beautiful and vulnerable parts splayed for the world to see, before buying a new one mail order and growing it from larva. The beetles, they stay larvae for eight months before becoming adults.

Watching the perfect, ignorant symmetry of the ants pisses me off. I grab a bottle of Calgon ‘Take Me Away’ body spray from my purse and spray the line a few times, floral droplets misting down, and get on all fours. The bugs scatter, scrambling around in satisfying circles. I lean in closer to see one ant’s legs working the liquid off its antennae, touching the drops and circling, lost without the scent of its fellow workers. Anger gives way to curiosity. I mist them again, and again, until I make a puddle and watch as one of them swims around, then stops moving completely. A few struggle still. I get up, bored with their suffering. Daddy hasn’t even noticed me crouched on the floor.

In the bathroom, I turn the fan on to drown out the crinkling plastic. I take the cap off one of the pregnancy tests and place it on the vinyl countertop. Feet shuffle across the ceiling. I sit on the toilet and spread my legs, placing the test between them, and aim a stream of piss.

An older woman, Ruby, had lived upstairs for several years, but she moved after falling behind in rent, leaving most of her furniture behind. Ruby had placed the key under her doormat before she drove off in a small Subaru packed to the brim with coolers, towels, a tennis racket (though I never once saw her take the tennis racket anywhere), and many plastic tubs. I snuck up there to look inside before the landlord found out she’d left. She’d trashed the place: cigarette butts pressed into the institutional carpet, dried spills, cereal bowls brown with crust. On the coffee table I found a shoebox filled with her old name tags: Ruby, Housekeeper; Ruby, Mcdonald’s; Ruby, Museum of Crystal Bridges; Ruby, Lunch Admin, Ahst Community School District. Mixed in were Happy Meal toys, nail polish, an old purple double dong grayed and dirtied at its tips, two lotto scratchers, and a lavender button that said She’s getting married, I’m just getting drunk, in curly font. Not long before she left, I’d gone to the county court office to get my license renewed when I saw her walk out through the glass double doors with an older man on her arm who was dressed in a denim pearl-snap shirt and a tan cowboy hat. The man had taken off his hat, rubbed his peppered beard, and nodded at me as they walked past. I’m sure they were on some beach in Texas sipping Coors while the new tenants scrubbed the stains out of her carpet. I’d rifled through the remaining items, hungry to hoard what I might not get otherwise – the double dong and a crocheted wedding gown from the 1970s, a good get – and kept the apartment key in a jewelry box on my dresser. Sometimes I pulled the shoebox out from under my side of the bed to stare at the dong, wondering if I’ll ever use it. Daddy doesn’t know I have it, at least I don’t think he does, and it’s always good to have a little secret now and then.

I finish pissing, click the plastic cap over the cotton wick of the test, and wipe a drop away with my thumb.

‘Do you ever wonder what our future child will be like?’

I pose the question while Daddy and I are lying in bed. What Daddy is thinking, I can never tell by the look on his face. I ask him questions hoping it will bring us closer.

‘No,’ he says. ‘I don’t think about the future like that.’

He rubs the keloid on his jaw, then the bags beneath his eyes. The way he carries himself, his chest and shoulders are always tense – a taut exhaustion that lets go only when he is drunk enough to sleep.

‘When I think about the future,’ he says, ‘I think about winning the lottery.’ His eyes light up when he says it.