3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

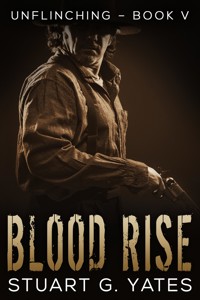

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

It is the mid-11th century, and Harald Sigurdsson is now king of Norway. It seems that all of his ambitions are fulfilled, until he receives a visit from the King of England’s brother.

Banished by the king, Tostig Godwinson is a man on the run, full of jealousy and loathing. If he could persuade Hardrada to seize the throne of England, he could then become Earl of the North. Such a venture, however, could prove dangerous.

Meanwhile, Nikolias pursues Andreas across the vastness of Central Europe, to rescue his love, Leoni. Andreas has his heart set on killing Hardrada, as revenge for the wrongs done to him by the giant Viking. Can Nikolias find him in time, and save Leoni?

Against the backdrop of the furious struggle for the throne of England, this story of love, death, treachery, and destiny comes together on the blood-soaked fields of battle in the final part of Stuart G. Yates's Varangian series.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Destiny

VARANGIAN

BOOK FOUR

STUART G. YATES

Contents

Introduction

Part I

1. A Woman’s Tale

2. The Guilt And Shame Of It

3. My First Introduction To Hardrada

4. Return To Saint Anselm’s

5. To Jaroslav

6. The Rus Prince’s Hall

7. Tales Of Sicily

8. Of Bolli Bollason

9. Of King Harold’s Plan

II. King Of The North

10. Plans For Kingship

11. To Zealand

12. Campfire Conspiracies

13. Assassination

14. King At Last

15. Nikolias

16. King Harald

17. Nikolias

18. To England

III. Tostig

19. The New Earl

20. Displeasure

21. Across The Sea

22. Sweyn

23. To England

24. Plans

25. Intrigue In Flanders

26. Plans Agreed

27. Once More To England

28. Flight In The Night

29. Ranulph

IV. Hardrada

30. In Norway

31. In The Court Of The Norwegian King

32. Departures

33. The Western Isles

V. To The Bridge Of Death

34. Morcar of the North

35. Ranulph

36. To Fulford

37. Battle

38. At Winchester

39. To Stamford

40. Aftermath

About the Author

Copyright (C) 2024 Stuart G. Yates

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2024 by Next Chapter

Published 2024 by Next Chapter

Edited by Graham (Fading Street Services)

Cover art by Lordan June Pinote

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author's permission.

For Janice, as always

Introduction

I am Ranulph of Hornsea and have lived in the Priory of Saint Anselm for as long as I can remember. My Prior, the esteemed Father Grenwald, has instructed me to put pen to paper to record the events of the last few months lest they should become distorted in the years to come. This undertaking has required me to travel widely across this land, and across the sea to the kingdom of the Norse and the fabled king, Harald III of Norway. I recount what I have seen and heard with an honest heart, guided by my faith in God and a desire to commit this story for future generations so that they may learn and appreciate the deeds of great men.

PartOne

A Woman’s Tale

It began that bright day when I, together with the novice Antony, tramped across the downs towards the village of Much Winton. Several elders had come to the Priory of St Anselm’s to beg our service. At first sceptical over what they recounted, such was their frenzy that Father Grenwald, our prior, at last, agreed and, well-resourced with various herbs and concoctions, sent us on our way. We arrived some three days later, the fresh sea air invading our nostrils and fortifying our spirits.

Ominously, perhaps, no sooner had we passed through the village entrance than the sky blackened, and rain pounded down upon our heads.

“We’ll put you up in Stephen’s barn if that is to your liking,” said Beadwof, the elder who had led us there.

“Stephen be a Norman name,” muttered Antony.

Beadwof’s hard stare settled upon my young companion. The novice wilted under its fury.

“Norman travellers came here and built that barn.” A gnarled finger pointed towards where we were to rest. “It’s as fine a building as any of us have ever seen.”

“I meant no criticism,” said Antony quickly. Blinking, he turned to me for support. “Merely an observation.”

I smiled, unsure why Beadwof should take such exception to Antony's words. “Let us go and make ourselves comfortable.” My gaze locked on Beadwof’s. “We shall then speak with the woman.”

Later, having shaken out the worst of the water from our habits, we prayed for divine guidance. Emerging into a squall, I doubted our pleas had been answered.

“This does not bode well,” grumbled Antony.

“If this is the only obstacle we have to navigate, we will be well-blessed, rest assured.” I smiled reassuringly. “Have faith.”

Catching sight of Beadwof standing in the entrance to a sagging hovel, beckoning for us to approach, we threw our cowls over our heads and ran bent double towards him. Even with my head down I could not fail but see, in the village square, a man bound and locked within a cell of iron. He sat huddled within himself. Having no roof, the cell could provide no shelter as the rainwater poured down upon his head. Black eyes peered towards me, and it seemed to me that he had taken a beating before his incarceration. I shuddered at the sight and continued towards the hovel.

Inside, a tiny crackling fire gave off an inviting orange glow. There were several villagers crouched around it. Beyond them, set against the far wall, a woman lay upon a moss-stuffed truckle bed. Her eyes were wide open, and she was shivering, surprising given how warm the interior proved to be.

“She’s been like that for the past four days or so,” explained Beadwof. “She left to go to market over at Seaforth ten days ago and when she finally returned, she was like this. We can’t get a word out of her.”

I nodded towards Antony. “Boil water,” I said. “Add three spoonfuls of Asian spice and two of ground ginger. We may increase the ginger as necessary.”

Bowing, the novice went to find a bowl and do my bidding.

“We thought it was a death-fever,” said Beadwof, “so one of the old women prescribed Moonflowers.”

The times I have come across this sort of uneducated dabbling in medicine are countless. I bunched up my fists for I was furious. “You are a fool for following baseless advice. Where is this crone that offered up this nonsense? She should be flogged for dabbling in such sorcery.”

The man wilted under my assault and backed off, head lowered, his previous aloofness swept away in an instant. “She is nought but an old woman, Father. She knows well the ways of the earth.”

“I’ll not have devilry here,” I hissed, rounding on the others assembled there. They shrank away from my words. “This is nothing but ancient myth and hearsay. I’ll not have it, not in my presence!” I took a large breath. “Get out, all of you!”

It took but a moment for them to retreat, leaving myself and Antony alone to deal with the stricken woman.

We administered the brew I’d ordered to be made. Supporting the back of her head, she took tiny sips from the wooden goblet I held to her lips.

As I knew it would, the colour returned to her cheeks, her eyes grew bright, and her body relaxed. I lay her gently back to a resting position.

“Can you tell us what happened?”

With a little effort, she turned her head to face me. The tears welled up under the bottom lids of her eyes. “Oh Holy Father,” she said, voice brittle, wavering. She reached out a hand to the wooden crucifix dangling from my neck. Its touch seemed to give her renewed strength.

I curled my hand around hers. “Be reassured, my child, the Lord will guide you. Speak.”

“I was at market,” she said and swallowed hard. I nodded in encouragement. “I saw him from a distance, his face so … handsome, it has to be said. He smiled and, may God forgive me, I felt a thrill race through me. He was a thegn, dressed in fine woollen clothing, hair well combed, shoes stout and fine. A man of wealth. Privilege. For such a man to show me favour was undreamt of.”

With her slow but relentless recovery, it was clear for all to see that she was comely, her skin lustrous, cheekbones so prominent. A beauty.

“Many must have fallen under your spell,” said Antony.

I shot him a vexed look. “There are no spells here, Antony.”

“It is but a saying, Father.”

“An unfitting one. Remember your place.”

He bowed and shuffled off into the corner.

I returned to her. “What is your name, child?”

“Claennis.”

“Tell me what occurred, Claennis.”

“I am afraid, Father. What if I am judged a harlot?”

“God is our only judge, Claennis.”

“I am ashamed.”

“Tell it.”

She closed her eyes for a moment as if gathering herself. “He spoke to me. Such kind and gentle words. He told me he was the king’s brother and that he would give me a life unlike any I could imagine.”

I slowly drew in a breath. “The king’s brother? He said that?”

“Yes. Tostig was his name. Such bearing, such command. I felt honoured, Father that such a man as he should show me favour.”

“You lay with him?”

Her eyes closed again. “Lord forgive me, yes, I did. Many times. I have never …”

“But you are married?”

“Was, Father. My husband died last winter. I have been alone since.”

The burning sensation around my jawline developed. Despite anticipating such a confession, her words still came as a shock. I am not worldly in such matters and although many a monk has partaken of carnal pleasures, I have always resisted.

“Such was the intensity of his love, I felt as if I were being carried away to heaven. I’m sorry.” Her grip on the crucifix tightened.

My tongue grew large in my mouth. “Heaven?”

“It was divine, Father. His body, so close to mine, the things he did. I never knew I could experience such sensations. It was so pleasurable, I screamed, Father and that is when the soldiers came. They burst into the little barn he’d taken me to, half expecting to find a murder taking place, I shouldn’t wonder. There were furious words before Tostig managed to send them away. He was laughing out loud, head thrown back, and he stood over me, confident of his magnificent body. I was thrilled at the sight of him. He put his fists on his naked hips, licked his lips, and said, ‘How would you like to come away with me? I’ll love you every night and every morn and you will be so filled you will never wish to leave.’ I am ashamed to say, I consented.”

“It was as if you were drugged,” said Antony from the corner.

This time I did not admonish him. His words were exactly what I myself was thinking.

“Yes. I was. Drugged by him, his ardour. I could not resist. So, he took me down to the port and introduced me to his crew. They were a fearful lot, but Tostig had such command over them that none dared approach me. Set off-centre stood a little covered shelter and it was into this that he put me, supplying me with numerous fur skins and woollen blankets. I did not know what was to become of me but so consumed was I by his insatiable loving that I cared not. He took me there and then, ravishing me repeatedly. Afterwards, he stepped outside. I heard his great booming voice calling the men to their oars and soon we set off.”

“The king has banished Tostig from these shores,” I explained. My throat tight with her retelling. “No good can come from any liaison with him.”

“I know that now, Father. But what could I do at the time? I was lost to him.”

“It is the absence of his love-making that gives you fever?” asked Antony.

“You carry his child?” I gasped, dreading her answer. If she bore Tostig’s child, King Harold would seek her out and put her to death. There could be no doubt about that.

She shook her head. “Dear Lord, no! I cannot, Father. I am barren.”

“And there you have it!”

It was Beadwof, bursting into the hovel, face alive with fury. Clearly, he had been listening outside the door.

“How dare you interrupt my meeting,” I snapped, getting to my feet.

Antony stepped forward, to block Beadwof’s approach. Without a thought, the big villager swatted him away like a fly with a swinging, back-handed blow, sending my novice crashing to the ground.

Breathing hard, barely able to control himself, Beadwof railed like someone possessed, “I knew it! Barren. That’s God’s punishment on this whore, Father! I thought perhaps she was possessed, that was why I came for you, to banish the demon inside her. But now I know the truth of it, so help me. Leave us now, Father. Your prayers have no use here. She is a whore, and we shall deal with her in our own way.” He drew a knife from his belt. “Step aside, Father.”

“I shall not,” I said, my words sounding stronger and more assured than the twisting and rolling sensations in my guts made me feel. I saw the look on Beadwof’s face and was sorely afraid.

“So help me, Father, I’ll take you with her if needs be.”

He brandished the knife.

I stood my ground whilst behind me, Claennis struggled to her feet.

All at once, Antony reared up and landed the quarterstaff he’d managed to find in a corner with bone-crushing force across the back of Beadwof’s head, knocking him face-first to the ground. He lay there making no sound as the blood plumed around his inert form.

I got down next to him to check for any life signs. I froze in horror, rocked backwards, and made the sign of the cross. I slowly raised my head to look deeply into Antony’s face. “He’s dead,” I said.

Claennis, crumpling, wailed and Antony, the staff falling from his fingers, staggered backwards, his face at first ashen. Shortly, however, he rallied himself and grew defensive. “Better it is he who is dead rather than you, Father.” He showed no remorse, his face tense, hard.

We had come to this bedraggled place to give aid to a poor, confused girl. Instead, we had committed murder and now must face the consequences.

Together, Antony and Claennis manhandled the body over into the far corner and covered it with all sorts whilst I sat in a daze, still not ready to believe what had happened. I could not face that Antony had murdered Beadwof with such breathtaking indifference. A novice, devoting his life to God, to dispense death in so casual a manner caused me to question everything we stood for.

“We have to go,” he said, standing over me, showing great resolve, transformed into the more confident of us both, taking control as all I could do was sit and stare. I looked up at him. Struck dumb, as I was, I could barely mutter a reply.

“Come on,” he said, pulling me to my feet by the sleeve of my habit. “If we’re lucky they won’t discover the body until we are well gone.”

“But Antony…” I managed in a feeble-sounding voice. I wanted to harangue him, pound at his chest with my fists, demand he took responsibility for his murderous actions, but I could not. There was no strength left within me, not anymore. I turned to where Beadwof’s body lay, covered over like a discarded piece of rubbish. Mere moments ago, he was a warm-blooded, living person, now a lifeless heap of nothing. “What are we to do?”

“We’re to leave,” said the girl, brushing past me, features hard. For her, this incident was nothing out of the ordinary. No doubt, she had experienced death in all its aspects many times before. This was the life she had come to know. Brutal and fleeting, Beadwof’s murder a trivial episode, nothing to cause her concern.

“We shall return to the Priory,” said Antony, as if he’d planned all this. A premeditated act. A sin.

I baulked at his suggestion. How was I to face Father Grenwald with the knowledge of what we’d done? This ghastly place! We’d come to aid a young girl, seized by demons, so they had said. Her story said a lot more. Tostig proved to be the demon. And now this. Murder. How had everything gone so wrong so quickly? Pressing my thumb and fingers into my eyes, I did my best to rid myself of the horrific images racing through my mind. I failed.

“Father,” insisted Antony, his voice verging on the frantic, “we have to leave!”

“We must pray,” I said, “pray for forgiveness.”

“We can do that on the road.”

“No,” I snapped, glaring at him, “we pray now, before God and ask for forgiveness and guidance.”

I dropped to my knees and Antony, after a slight hesitation, joined me.

The Guilt And Shame Of It

Claennis was adamant we free the man in the cell. Already villagers were looking at us with suspicion as we stepped out into the daylight. One approached Antony, asking where Beadwof was, and the novice eloquently dissuaded them from investigating the hovel. His confidence and ease at using an invented storyline brought me considerable unease, I have to admit.

I harangued a passing villager and demanded he open the cell. He did not take much persuading, my furious expression enough. He ran off to fetch the key, returning a few moments later with two others.

“I am Eadward,” announced the first of these men. “I am an elder of this village, together with Beadwof. Has he given permission for this man to be freed?”

“He has,” put in Antony immediately.

Grunting but thankfully not arguing, Eadward duly opened the cell. The others bundled the prisoner into the open. The rain lashed down, soaking us all through, making the scene into a deeply macabre one.

“We shall take him from here,” I said.

Frowning, Eadward shifted his weight from one foot to the other, “Are you certain, Father? He is dangerous, I am certain of it.”

“We shall be careful,” I said.

With much bowing and fawning, we left the village, all of us doing our utmost not to rush. The poor fellow we had helped release, hung in our arms as Antony and I carried him towards the village entrance, Claennis striding ahead of us. I studied the man's face as we went across the square and saw, with a shock, how much his body appeared punctuated with cuts and bruises from the severe beating he had taken. In some perverted way, the sight calmed me, making me realize that we had done him a great service by releasing him. I did not know what he had done, and perhaps I was grasping at anything to ease my conscience, but I believed this was the Lord’s doing, His hand guiding us in our actions.

We did not look back but continued on, heads bowed. I shot a sideways glance towards Antony, whose face remained as cold and emotionless as ever. Had I misjudged him, I asked myself. Arriving at the Priory gates in the back of an old hay cart some years before, he appeared frail, frightened, pleading with us to help him. We took him in and gradually, over the months and years, he emerged as a thoughtful and hardworking member of our community.

And now this.

Killing a man without conscience, as if Beadwof were nothing more than an irritating insect. Antony was not the man I believed him to be.

Later that evening, under the shade of a small, wooded glade, we dried out our clothes. I again prayed for forgiveness, but no amount of praying was ever going to erase the horrors of what I had witnessed. For his part, Antony appeared relaxed and unaffected, treating everything with disdain.

“He would have killed you,” he said as we huddled around a small campfire. We had little to eat. A few biscuits and pieces of hard bread we had managed to salvage from our saddlebags. Most of it was nothing more than a mush but Antony, displaying further talents, managed to fashion the congealed mess into flat cakes and, placing them on hot stones, baked a most digestible supper.

“Father,” he said after a long pause, “you must not blame yourself.”

“I do not.”

“I see it in your face that you do.”

He was right, of course. I should have done something, shouted a warning, pushed Beadwof aside. Anything.

“If I had not struck him, you would not be here now. None of us would be here now.”

“You cannot say that for certain, Antony.”

“His intentions were obvious, Father. They would have executed Claennis in the village square.”

I looked askance at where the girl sat out of earshot, so close to the rescued man, who we now knew as Artry, they could have been joined at the hip. She giggled and nuzzled into his neck. It was clear to me, despite my naivety in such matters, that they were lovers. “Perhaps.”

“There is no perhaps about it, Father.”

“You talk as if you know a good deal about such things.”

He dropped his gaze and stared into the fire’s crackling embers. “I was little more than fifteen summers when I first came to the Priory. My parents were killed before I was ten and it wasn’t long before I fell in with a band of brigands. They brought me up and it was a violent, uncompromising world to which they introduced me. We robbed travellers, attacked official baggage trains, looted rich homesteads. We feasted on the best venison, drank the finest ale. As the years passed, I became skilled in the ways of the bandit. I never stopped to question anything, until the day one of the gang, a man I only knew as Sten, set a small croft alight. Soon the air was filled not only with acrid smoke but with the screams of a child. Without thinking, I fought my way inside, struggling through the blaze, and found her. A tiny child, no more than a few months old. God was with me that day. Holding her close, wrapped in my undershirt, I brought her out. Sweyn grew angry, berating me for being a fool, saying that I should have let the child die. He strode forward and went to wrench the babe from my arms. I whirled and kicked him, hard, between the legs. He fell, throwing up over the ground and before I knew what I was doing, I took my dagger and plunged it into him. The babe instantly stopped her crying, perhaps as stunned as I was.”

“You murdered him?”

“I would not use that word, Father. The man was a beast. Worse than a beast. A vile, thoughtless killer. I had no regrets, not then and not now. The parents, who had found a safe place in which to hide, rushed to me, took their child, blessed me for what I’d done. The faces of the others in my gang, however, told me everything I needed to know. I left. I had no choice. I wandered aimlessly across the land until an old trader, delivering goods to a nearby town, helped me into the back of his cart and took me to Saint Anselm’s. You know the rest.”

“I had no idea of your background.”

“If you had, would it have made a difference to your decision to let me stay with you?”

“It may have done.” Thinking back to how happy Antony had been when I showed him into the Priory dormitory, his face alight with gratitude, I could not reach a decision. He seemed so innocent, wide-eyed, a vessel to be filled with the grace of God.

I wondered what other future miscalculations I would make.

My initial thought was not to press the man sitting across from us. Artry appeared a most ferocious fellow, long straggly hair hanging down to his shoulders, a weather-beaten face encased with a tangled beard, the eyes of a demon glaring out under his heavy brows. I doubted he was Saxon. As Claennis explained, my suspicions proved correct.

“Artry here,” she said, munching on her pancake with relish, so ravenous I did not think she had eaten for days, “he served on Tostig’s ship. He helped me, brought me to my village in the hope of curing my sickness. Instead of praising him for helping me, they locked him in that horrible cell, with no food or water.”

“He rescued you from Tostig?”

She caught my bewildered look and nodded. “On that first voyage, Tostig changed. From being so attentive and kind, he grew impatient, brutal, forever demanding things of me I knew were wrong. It was when he beat me that Artry came to my rescue. One night, after we raided yet another small coastal village, Artry spirited me away. People from the first village we came to were afraid of us and drove us away, but we managed to find sustenance in a tiny hamlet a little way inland. It was from there that we managed to find the way to my village.”

“But why,” put in Antony. “Why would he help you?”

Artry cleared his throat, looked down, spoke in a small, uncertain voice. “I worshipped her. Tostig, he treated her as if she were his plaything, his property. I swore to help her, to show her another way.”

“Artry is kind where Tostig was an animal. I made such errors, such mistaken decisions, believing I would live a better, more meaningful life. But all Tostig wanted was to use me. His thoughts and ambitions lay in only one direction – to overthrow his brother, seize the northern lands, and put Hardrada in the king’s place.”

Frowning, I looked across at Antony. “Hardrada?” Antony shrugged and shook his head.

“King of Norway,” said Artry. “He has a claim to the throne of England, one promised to him by Harthacnut many years ago.”

“I do not know of these things,” I admitted. “His claim is supported by Tostig?”

“So he can rule,” said Artry, “and reap revenge upon his brother. It is a shameful ambition. I know Hardrada well, served with him on his journey from Miklagard.”

“You speak names of which I know nothing.”

“Then let me try to enlighten you, priest.”

I acquiesced and settled back to listen to what this rough, ill-mannered brute had to say.

“I shall tell it without comment or judgement,” began Artry. “I was loyal to Hardrada, although he was not yet known by that name, and remain so to this day for he was a great man, a legendary warrior. I served him well in the great city for many years as a member of the Varangian Guard. Adventures, the like of which I could tell for a hundred years, were numerous and rewarding.” He drew in a breath and as he recounted the tale, I was transformed to that distant and curious place. New Rome. Miklagard. Many know it as Constantinople. As he told his tale, Artry’s voice reflected the golden spires of that fabulous city, slipping like honey from his coarse mouth.

“We landed in Fornsigtuna almost twenty years ago,” he began. “I was with him…”

My First Introduction To Hardrada

The Skald stood on the headland, the wind wrapping the hem of his long, coarse robe tight around his legs, legs which were planted wide like pillars to bolster him against the brewing storm. His head was adorned by a twisted crown of thorns, interlaced with greenery, berries, and acorns, and his name was Hekkr. People from miles around travelled to listen and marvel at his words. Poems, which ran well into the night, and remained in the memories of the listeners for ages to come, were where his finest talent lay. Tales so vivid and inspiring it reduced the strongest to tears. Such songs, such deeds. The greatest Skald of his age.

As he stood and watched the far-off boats anchoring in the comparative safety of the cove far below, he composed the words that would paint the pictures of this most improbable of days.

Hardrada’s return. The man of legend who fought and almost died to save the life of his brother, who sailed towards the horizon to serve and love the golden empress of Miklagard. A true Viking, an adventurer without equal, come again to the Norse to reclaim his birthright and rule the kingdom. Rich, strong, a warrior of renown, with so many tales of his own to tell. If he agreed to tell them, of course. Share them, at least, with Hekkr, so the tales might reach across the vast empty plains, to the west and the open sea, to the north and the expanse of snow.

Head bowed, he picked his way along the steep path, nothing but a trickle of grit running between thick outcrops of gorse and heather. With each step, the sound of voices drew closer, of men savouring their first experience of home for so long. Men who had served, without question, the towering giant of the man standing amongst them, his golden hair whipping across his face, who turned his dazzling blue eyes in Hekrr’s direction, his hand curling around the hilt of his sword.

“Welcome Son of Sigurd,” cried Hekrr, his voice piercing the wind, causing them all to stop and squint. “I am Hekrr, here to bid you welcome.”

“How do you know it is I?” asked Hardrada, grim-faced, ready to draw his blade, and Hekrr knew the Viking was alert to danger, the threat of ambush. This land may be his homeland, but it was one he no longer knew, one filled with mystery and possibly danger.

“Your coming was foretold,” said Hekrr, drawing up close, his bare feet splayed on the cold, winter sand.

“Who by?”

“None who wish you harm, my lord.” Hekrr lowered his head. “Ordinary folk, both far and wide, have long lamented your parting. They have held on to the hope that one day you might return, their prayers now answered at last.”

“Prayers?” Hardrada shook his head. “It is not their prayers which have led me here.”

“You do not believe?”

I could see how Hardrada struggled to keep his temper in check. Over the many years of dealing with people from every level of society, he’d learned, often painfully, that forbearance and patience were his best allies when listening to the ramblings of others. “I’ve lived a lifetime surrounded by death, betrayal, lies, and suffering. I haven’t taken much belief from any of that.”

“I’ll describe the words of God to you, my Lord.”

Around them, the last of the crew, of which I was one, clambered from the nearest draker and made their way along the path, stretching weary limbs, flexing knotted muscles. Hardrada stared towards the sky and took in a huge breath. Another man, not as tall but equally as broad, came up beside him.

“We have our welcome, Ulf,” said Hardrada.

Ulf grunted. “Doesn’t take them long, does it.”

Hardrada returned to his former, impassive self and took in the sight before him. “I know you for what you are,” he said. “A skald, or court poet. Perhaps something more. A shaman. Holy man, mixing tales of the old ways with those of the White Christ. That way you appeal to all who struggle to find meaning in a world of uncertainty and dread. But I have no need of you, so be on your way … in peace.”

“He means for you to go away,” said Ulf through gritted teeth, hand dropping to his sword, “I can always help you if you so wish it.”

Ignoring Hardrada’s friend, Hekrr moved closer, tipping his head slightly. “I will not keep you, only to say this. Welcome home, my Lord Harald. We have all waited long for your return and now you have set foot upon our land again, we can rest easy. For salvation is here.”

He lowered himself to one knee, smiling, face turned upwards as if drinking in the grace of his long-awaited lord.

Ulf guffawed, “By the gods, you do not want to send this one away – he loves you!”

Hardrada shot him a sideways glance. “Don’t mock the afflicted.” He eyed Hekrr, considering the man’s words. “Salvation? You talk in riddles, skald. I’m not one of your audience, so temper your flowery language and say what you need to say.”

“You went south in search of answers,” continued the Skald, undaunted, “and your people have longed for your return. The tales of your exploits have reached our ears and the sagas have been sung.”

“Sagas? What sagas?”

“Of you, my Lord. Your fame has reached far. How you served the emperors of Miklagard, found the love of the empress, smote your enemies. The halls have rung with tales of heroism, love, betrayal. And now you are here, with a new wife, come back to the bosom of your people, to lead us once more to greatness.”

“Sounds like something from the old days,” continued Ulf. He leaned forward and jabbed at the skald with a thick forefinger. “Nothing like a Christian tale, eh? What are you, priest or shaman?”

“I am as our lord has stated; a poet, a singer of songs. The people still have desires for such things. Listening to stories around a campfire, or huddled together in a longhouse, we all have need of stories, a chance to escape from the world.” He stood up. “You have returned, to be our king.”

Ulf grunted and made a face, but Hardrada stopped, his eyes narrowing. “A prophesy?”

“Songs.”

“Songs based on what? Who else knows of my return?”

The air grew cold and still. Even the last few men who worked taking supplies from the ships stopped on their way toward the nearby harbour town and looked. Everyone waited, only the skald appeared relaxed, indifferent to the growing sense of threat, anger, looming violence.

“We have always known.”

Hardrada and Ulf exchanged a look. “More riddles,” said Ulf at last.

“Tell it straight,” said Hardrada, his patience at its end now. This poet, this singer of songs riled him, ignited the anger he always struggled to keep under control. “You said people who knew of my coming do not mean me harm.”

“That is so … but soon, this news will spread. You must be wary, my lord. For there are many who are jealous of you, of what you have achieved.”

“Well, I have still much to achieve, as you probably know, given who you are.”

“To be king in your own right,” said Hekrr, nodding. “Yes, I know it, but to succeed you must first defeat Magnus, the king who rules, and to do this, you will need help.”

“I need no help,” snarled Hardrada. “I have money enough to raise an army. Money enough to—”

“And enemies enough to thwart your every move.”

Ulf sucked in his breath, “By the gods, I’ll not suffer this insolence!”

Ulf’s hand curled around the hilt of his sword, but as he drew it, Hardrada’s hand closed around his old friend’s. “Stay, Ulf. I’ll know who these enemies are.”

“From your past, Harald Sigurdsson,” continued Hekrr, his voice even, without hesitation or fear. “Men such as Kalv Arnesson and Thorir Hund. Women such as Zoe, the empress of Byzantium, whose reach is long. And someone from your past who will end your future.”

“What nonsense is this,” spat Ulf, tearing his hand free of Hardrada’s. “You have the gift of prophecy, as well as the telling of stories, for that is all they are – stories!”

“How do you know all this,” said Hardrada, ignoring his friend’s outburst, all of his attention on the skald. “Have the stories about me circulated throughout the entire world?”

“Almost, my lord. I do not prophesise; I tell of things that will be. That is all. The only way to smite your enemies is to join with the Dane, Sweyn Estridsson, make common cause and bring peace and prosperity to the land of the Norse.”

“You are an emissary of his, is that who you truly are? Sent by him to gain my comradeship?”

“You told me how once you saw in the sky a draker, sailing across the firmament, a sign you are and always will be a Viking.”

Hardrada gaped, his mouth falling open, the blood draining from his face. “How can you know such a thing?”

“Estridsson did not send me, Lord. You did.”

Hardrada’s face revealed nothing of the confusion raging around inside him. “You must have overheard this tale. How else could you—”

“I know you saw such a thing, a longship sailing through the clouds. Now I would ask you to look again.”

He gently took the giant Norseman by the arm and steered him away from the others who stood, transfixed, as if all of them were struck by the enormity of what was about to happen, of something unseen, powerful.

By the lapping waterside, they stopped. Hekrr’s voice came as if from out beyond the water, from a distant, unfathomable place. “Look towards the sky, my lord, and see what lies within your heart, what you know to be true.”

Despite himself, Hardrada slowly turned his face skyward and there, within the clouds, he thought he saw a vague collection of figures, of places, of mountains and forests, and a blighted plain, stretching out beyond a bridge. A bridge upon which men fell and died. And one man. A man he knew.

“Destiny,” whispered Hekrr, “your destiny, my lord. But before this, you have much to do, to secure your kingdom, your place in history. And it begins this very day.”

Alone, Hardrada’s face moved towards the water, and he gazed upon the gently rippling surface. For years, after his return from Constantinople, Kyiv passed for home, a place where he could forget, make plans, take Elisiv for his wife and all the while preparing himself for the journey home. He always knew obstacles stood in his way, that he would need more strength, more guile than ever before to win through and become king of the Norse. But he never considered his past might be his eventual undoing.

Lost in the images he had seen, he did not hear Ulf’s approach until his old friend laid a hand on his arm. “Harald? What is wrong?”

Hardrada’s eyes remained fixed on the water as he spoke. “I saw him, as clear as if he were standing here, right next to me.”

“Who, Harald? The skald? He has gone, taken as if by the wind, without a sound. What did he say to you?”

“He showed me …” Hardrada shook his head, becoming lost amongst his thoughts again.

Ulf waited.

At long last, a shuddering breath and Hardrada straightened his back, seeming to grow even taller. “I have much to do, Ulf. I must tread carefully, overcome those who seek to thwart my right to be king and I must seek vengeance on those who have wronged me. It will be a hard struggle, but I will prevail until … Until I stand beside a bridge, a bridge I do not yet know. But there I will meet him, and the story will end.”

“Meet him? It is you who now talk in riddles! Meet who?”

“My bane.” Hardrada turned and stared into the wide eyes of his friend. “Andreas.”

Return To Saint Anselm’s

I am in seclusion. As the daily life of St Anselm’s carries on around me, I spend my time in prayer, prostrate on the floor of the church, head bowed, the statue of Christ looking down at me, those piercing, unblinking eyes judging me.

We rode hard, the return journey to the Priory taking a mere two days. As we camped that final night, I pulled Artry aside, quizzing him about his tale.

“You recount what happened with Hardrada as if it were a story.”

“In many ways, it was, Father. It falls from my mouth with ease, and I cannot help but embellish and invent to make it more alive. But every word is true, I swear it.”

“You are no mere pirate, Artry. You may have sailed with Tostig to raid and loot coastal villagers, but you have a gift. The gift of the bard.”

He shrugged. “My father before me earned his living as a travelling teller of tales. My brother took it up, accompanied him and when he died of sickness, father took me with him. For several years we tramped the land, and the people would give us food, sometimes money, their eyes alight with wonder as my father told stories of Greece, of Rome, and sometimes Old Norse sagas. It was a craft I learned thoroughly.”

“You have lost none of your skills, Artry. I hope you will tell me more.”

“I will,” he said, his eyes settling on the distance. “My next part of the story I relate will travel to the present as Tostig himself becomes one of the leading players.”

“The king’s banished brother.”

“Yes. King Harold has declared him an outlaw and has sentenced him, and all who sail with him, to death if he returns to this land.”

“Then you were indeed wise to leave his service.”

“That was an unconscious happening, Father. Without Claennis, I would be with Tostig still.”

“Then we have much to thank her for. Your story is one which should be widely told.”

His jawline reddened and he squirmed a little under my gaze. He did not receive praise easily, and I did not press him further.

The following day brought us within sight of St Anselm’s. However, setting eyes upon the tall steeple of the Priory, a view that should have filled me with joy, all I felt was a horrible trepidation. After stabling our mounts, Antony showed our companions where they could stay whilst I sought out Father Grenwald to explain to him what had occurred.

He sat in his high-backed chair, face inscrutable, hands clasped together on his lap, eyes staring towards the floor as he listened intently. I waited, standing before him in his small chambers set beside the Priory cloister, in the west wing. It was a simple room, cramped, dark, a small writing desk set in the corner and, opposite, his bed. The Rule and various volumes of scripture were neatly arranged beside the desk. A well-burned-down candle was the only means of illumination save for a sliver of daylight trickling through a crack in the single, tiny, shuttered window.

I did not tell him the whole story. How could I? Antony, perhaps even myself, would be instantly ejected from our community. Instead, I told it as if it were an accident, that Beadwof had tripped and split open his skull as he fell. I said nothing of Antony’s indifference to the killing, preferring instead to focus on Artry’s tale.

“This man, Artry as he is called, is a renegade then, Ranulph,” Father Grenwald said, his voice soft, like himself. A kind, hugely intelligent, and learned man. A man whom everyone looked to for spiritual guidance, a man I admired and respected without question. “Do you trust him and his story?”

“I do, Father. I believe his heart is changed, that he had turned his back on the life he followed whilst under Tostig’s control.”

“You know anything of Tostig?”

“Only what Artry has told me, which isn’t much. His words were all of Hardrada, king of Norway.”