Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

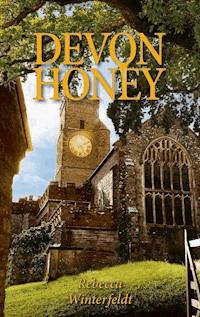

David and Sarah - an artist couple, live with their children in pitoresque Devon - South England. Sarah is considered one of the most important contemporary painters meanwhile David is struggling for success as an actor and playwright. The headmaster of the language school calls it »good luck« that accommodation could be offered with David and Sarah as a host family to the German woman Rebecca and her daughter. The pair spend their summer in that little village in Devon to learn English. But Rebecca, having escaped her passive-aggressive ex-husband, has to learn soon that appearances can be deceiving. Still suffering from her own past, she feels the shadow of emotional abuse within her host family. When Sarah leaves the idyllic house in Devon for a vernissage, Rebecca becomes closer to ambivalent David. However, the more she learns about his life, the more reality becomes distorted.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 52

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

David.

Forgive me. I had to write it. For the others on our path.

Don’t worry, I have changed the names and the places, no one will find you here.

With love, Rebecca

D avid entered the house. Fog had condensed into droplets on his dark curly hair. The floor creaked under his down-at-heel disintegrating leather boots. The dog shook itself and walked through the narrow kitchen into the sitting room. David went over to the kitchen table, hesitated for a moment, and then followed the dog into the room at the back. Sarah did not look up.

‘Good morning,’ said the German woman, as she entered the kitchen. ‘Toast will be ready in a moment,’ Sarah answered. ‘Thank you.’ The German woman sat down next to David, and poured some coffee into the chipped cup with the blue polka dots. ‘May I give you some too?’ she asked David. He looked at her.

‘David only drinks chicory coffee.’

David looked down at the steaming porridge in his bowl. Reflectively he took the honey spoon from the jar and let the golden-yellow honey flow over the porridge. He’s making waves, thought the German woman, and shifted a little closer to see the result. There was a smell of almonds. Someone pushed a plate onto the table at her side. ‘Your toast.’ Sarah looked down at her. Pale red strands fell over her haggard cheeks. ‘Thank you.’ They ate in silence.

The German woman looked at the porridge bowl, where the waves of honey were slowly dissolving into the mass. ‘You like porridge?’ she asked into the silence.

‘David eats porridge because he is of Scottish descent.’ The toast was hard.

‘What are you doing there?’ asked Sarah, and looked at the sheet of paper on the table next to David’s bowl. The page was completely written over, like a letter, with solid words, royal blue ink, very neat, with curiously ornamental letters, row after row.

And on the left half of the page, painted over the words – a half sun. Looking like a flower, a half-circle with rays made up of pointed petals.

It’s beautiful, thought the German woman. Sarah picked up the sheet and read what was written there. Then she looked down at her husband with a serious expression.

T hey stood in the sunny garden behind the house. The garden walls seemed to absorb the warmth. The scent of blossoming flowers over the grass mingled with the hum of bees. In the vegetable patch yellow pumpkin flowers gleamed; soft green leaves and tendrils grew towards the light. The first fruits, though tiny, were already visible. An antiquated wooden fence was still capable of preventing them from overspilling into the next door garden.

Behind the fruit trees of the other gardens was the medieval church. Here and there the coppery red of its sandstone could be seen through the leaves.

‘Tea?’ The German woman started. Sarah was looking at her, so she knew that she was addressed. ‘No thank you. I’d like to go into the church. They’re singing hymns.’ She thought of the transparency saying ‘Everyone invited’. And had to smile. Smiling, she turned to Blair. He was standing with his father in the shade on the terrace. Without meaning him, she asked, ‘Would you like to come? Do you like singing?’ ‘No thanks.’ The boy made a shy dismissive gesture. ‘I don’t like the Church of England.’ The seventeen-year-old had his mother’s slanting eyes and thin lips. David looked her in the eyes. But said nothing.

‘Well, I’m going then!’ the German woman exclaimed, with genuine cheerfulness, because things were actually different from usual. The breeze fresher, the scent more intense and the poppies an almost painfully bright red.

She took her little girl by the sticky hand, and moved off. ‘Let’s go to church, Schatz, quick, we can sing hymns, it’s just about to begin!’ she told the child, stumbling hastily down the overgrown path through the lush summer garden to the church. She ran. But it was too late.

The church bells started to ring, the vicar in his black cassock stood smiling in front of the heavy oak door, which was open. Two elderly women in pastel colours were standing in the entrance. ‘So, do you want a hymn book?’ The girl extended sticky fingers and took it from her.

The coolness of the church enveloped her. Like the many others who had been before her, in hundreds of summers long gone.

At the front there was a free pew. The second one, directly facing the altar. The German woman was pleased – they had a clear view of the church’s bright and airy spaces, the ancient stained glass windows. These were cracked in places, having failed to stand up to the pressure of the iron frames, which had rusted and lost their shape over the centuries. Only in the east window, above the altar, there was a colourful spectacle of mosaics – scenes from the Bible and kneeling knights, waiting for the blessing with bowed heads. The cross gleamed red on their capes. The white-haired clergyman stood calmly facing the grey altar. For three breaths she inhaled the stony air and looked forward to the lightness the music would give her.

The organist adjusted his position. The stool creaked. The vicar turned from the altar to face the congregation.

At this moment the heavy church door was thrown open. A man stood in the entrance, reached for a hymn book and made his way resolutely to the second pew. He stood next to the German woman. Surprised, she looked up at him.

The vicar looked across at him with an astonished expression, which a wave of minor chords flooded out.

‘I would like to welcome you to this memorial service for the dead. For those who died in the First World War, fighting against Germany.’ The organ raged, her knees gave way, the girl looked up at her mother with irritation.

She asked him, ‘Should I leave?’ David looked down at her: ‘No, it’s all right, Rebecca.’