0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Reading Essentials

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Earth and High Heaven was the first Canadian novel to reach #1 on The New York Times bestseller list in 1944 and stayed on the list for 37 weeks, selling 125,000 copies in the United States that year.

Set during World War II, the novel portrays a romance between Erica Drake, a young woman from a wealthy Protestant family and a Jewish lawyer and soldier. The young lovers are forced to confront and overcome the anti-semitism of their society in their quest to form a lasting relationship.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

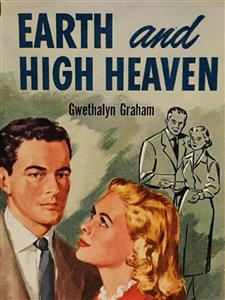

Earth and High Heaven

by Gwethalyn Graham

First published in 1944

This edition published by Reading Essentials

Victoria, BC Canada with branch offices in the Czech Republic and Germany

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except in the case of excerpts by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

For

I

One of the questions they were sometimes asked was where and how they had met, for Marc Reiser was a Jew, originally from a small town in northern Ontario, and from 1933 until he went overseas in September, 1942, a junior partner in the law firm of Maresch and Aaronson in Montreal, and Erica Drake was a Gentile, one of the Westmount Drakes. Montreal society is divided roughly into three categories labeled “French,” “English,” and “Jewish,” and there is not much coming and going between them, particularly between the Jews and either of the other two groups; for although, as a last resort, French and English can be united under the heading “Gentile,” such an alliance merely serves to isolate the Jews more than ever.

Hampered by racial-religious distinctions to start with, relations between the French, English and Jews of Montreal are still further complicated by the fact that all three groups suffer from an inferiority complex—the French because they are a minority in Canada, the English because they are a minority in Quebec, and the Jews because they are a minority everywhere.

Thus it was improbable that Marc Reiser and Erica Drake should meet, and still more improbable that, if by some coincidence they did, that meeting should in any way affect the course of their lives.

Leopold Reiser, Marc’s father, had emigrated from Austria to Canada in 1907 and owned a small planing mill in Manchester, Ontario, on the fringe of the mining country five hundred miles away; Charles Sickert Drake, Erica’s father, was president of the Drake Importing Company, a business founded by his great-grandfather which dealt principally in sugar, rum and molasses from the West Indies. Marc was five years older than Erica; when she was beginning her first term at Miss Maxwell’s School for Girls in Montreal, he was starting his freshman year at a university in a town about halfway between Manchester and Montreal. When he entered law school four years later, the original distance of five hundred miles had shortened to nothing; on the night of her coming-out party at the Ritz, he was within three blocks of her, sitting in his room in a bleak boardinghouse for Jewish students hunting down the case of Carmichael vs. Smith, English Law Reports, 1905. They must have passed in the street or sat in the same theatre or the same concert hall more than once, yet the chances of their ever really knowing each other were as remote as ever, and it was not until ten years later when Erica was twenty-eight and Marc thirty-three, that they finally met at a cocktail party given by the Drakes in their house up in Westmount.

During those ten years their lives had ceased to run parallel; some time or other, Erica had jumped the track on which most people she knew traveled from birth to death, and was following a line of her own which curved steadily nearer his. When she was twenty-one, her fiancé had been killed in a motor accident, two weeks before she was to be married; not long after, she awoke to the realization that her father’s income had greatly shrunk as a result of the depression and that it would probably be a long time before she would fall in love again. She got a job as a reporter on the society page of the Montreal Post and dropped, overnight, from the class which is written about to the class which does the writing. It took people quite a while to get used to the change. In the beginning, there was no way of knowing whether she had been invited to a social affair in the ordinary way, or whether she was merely there on business, but as time went on, it was more often for the second reason, less and less often for the first. When, at the end of three years, she became Editor of the Woman’s Section, she had ceased to be one of the Drakes of Westmount and was simply Erica Drake of the Post, not only in the minds of others, but in her own mind as well. She had no desire to get back on the track again, but it was not until the war broke out that she realized how far it lay behind her.

In June, 1942, she met Marc Reiser.

None of the Drakes had ever seen him before; he was brought to their cocktail party by René de Sevigny, whose sister had married Anthony Drake, Erica’s older brother, two months before he had gone overseas with the R.C.A.F.

Almost everyone else had arrived by the time René and Marc got there. Having caught Erica’s mother on her way to the kitchen, where the Drakes’ one remaining servant was having trouble with the hot canapés, René had introduced Marc, then got him a drink and went off in search of Erica, leaving Marc with no one to talk to.

He found himself all alone out in the middle of the Drakes’ long, light-walled drawing-room, surrounded by twenty or thirty men and women none of whom he knew and all of whom appeared to know each other, with René’s empty cocktail glass in one hand and his own, still half full, in the other. At thirty-three he was still self-conscious and rather shy, and he had no idea what to do or how to do it without attracting attention, so he stayed where he was, first making an effort to appear as though he was expecting René back at any moment, and when that failed, trying to look as though he enjoyed being by himself.

He finished his drink, having made it last as long as he could, and then attempted to get his mind off himself by watching the other guests gathered in small groups all around him. When you look at people, however, they are likely to look back at you. Marc hastily shifted his eyes to the plain, neutral-colored rug which ran the full length of the room, transferred one of the glasses to the other hand so that he could get at his cigarettes, and then realized that he needed both hands to strike a match. He put the package of cigarettes back in his pocket and went on standing, feeling more lost and out of place than ever.

He had had an idea that something like this would happen, and when René had phoned to ask him to the Drakes’ he had first refused, and then finally agreed to go, only because René said that he had already told Mrs. Drake that he was bringing him. Marc disliked cocktail parties, in fact all social affairs at which most of the people were likely to be strangers; if the Drakes had been Jews he would have stayed home regardless of the fact that they were expecting him, but the Drakes were not Jews and that made it more complicated.

A dark girl of about twenty suddenly turned up in front of him asking “Aren’t you George . . . ?” then broke off, smiled and murmured, “Sorry,” and disappeared just as Marc had thought up something to say in order to keep her there a little longer. There was another blank pause of indefinite duration, then a naval officer swerved, avoiding someone else and jarring Marc’s arm so that he nearly dropped one of the glasses, apologized and went on.

The scene was beginning to assume the timeless and futile quality of a nightmare. He glanced at his watch and found to his amazement that it was only six minutes since René had left him, which meant that, adding the ten minutes spent in catching up with their hostess on her way to the kitchen and finding their way to this particularly ill-chosen spot in the middle of the room, they had arrived approximately a quarter of an hour ago.

What is the minimum length of time you must stay, in order not to appear rude, at a party to which, strictly speaking, you were not invited, and where it is only too obvious that no one cares in the least whether you stay or not?

“Excuse me,” said Marc, backing up and bumping into an artillery lieutenant in an effort to avoid someone who had bumped into him. He turned and said, “Excuse me” again, and then identifying the lieutenant as a former lawyer who had been at Brockville on his O.T.C. in the same class as himself, although Marc could not remember ever having spoken to him, he said with sudden hope, “Oh, hello, how are you?”

The lieutenant looked surprised, said “Hello,” without interest or recognition and went on talking to his friends. It did not occur to Marc until later that if, like himself, the lieutenant had happened to be out of uniform, Marc would not have recognized him either. Having been turned down cold by the only human being in the room who was even vaguely familiar, Marc abruptly made up his mind to go, only to find when he was halfway to the door that René had vanished completely and that Mrs. Drake was blocking his exit, standing in the middle of the hall talking to an elderly man in a morning coat. He would either have to wait until she moved, or until the hall filled up again so that he could get by her without being noticed. To return to the middle of the room and the lieutenant’s back was unthinkable.

“. . . glasses, sir?”

“What?” asked Marc, jumping.

“Would you like me to take those glasses, sir?” asked the maid again.

“Yes, thanks. Thanks very much.” He put the two glasses on her tray, lit a cigarette at last, and having worked his way around the edge of the crowd, he finally reached the windows which ran almost the full length of the Drakes’ drawing-room, overlooking Montreal.

The whole city lay spread out below him, enchanting in the sunlight of a late afternoon in June, mile upon mile of flat gray roofs half hidden by the light, new green of the trees; a few scattered skyscrapers, beyond the skyscrapers the long straight lines of the grain elevators down by the harbor, further up to the right the Lachine Canal, and everywhere the gray spires of churches, monasteries and convents. Somehow, even from here, you could tell that Montreal was predominantly French, and Catholic.

“Hello, Marc,” said René’s sister, Madeleine Drake. “What are you doing here all by yourself?”

“I don’t know, you’d better ask your brother. How are you, Madeleine?”

“I’m fine, thanks,” she said, but she looked tired, and sat down on the window-seat with a sigh of relief. She was twelve years younger than René, with fair hair and a quiet, self-contained manner; her husband had been overseas since late in January and she was expecting a baby in August.

“Where is René?”

“Out in the dining-room.”

“Oh, so that’s where they all went,” said Marc. “I was wondering. Can’t I get you a chair?”

“No, thanks, don’t bother. I can’t stay long. Have you had anything to drink?”

“I had a cocktail when I came in. It’s all right,” he added quickly as she made a move to get up again. “I don’t drink much anyhow, and I’d much rather you stayed and talked to me.”

“You must be having an awful time,” said Madeleine sympathetically. “These things are not amusing when you don’t know anyone.” Her parents had died when she was a small child and she had grown up in a convent, so that her English was more precise and less easy than her brother’s. She smiled up at Marc and said, “It’s a long time since you’ve been to see us—could you come to dinner on Tuesday next week?”

“Yes, thanks, I’d love to.”

“About seven?” He nodded and she asked, “Have you met any of my husband’s family?”

“Just Mrs. Drake. That’s a Van Gogh over the fireplace, isn’t it?”

“Yes, ‘L’Arlésienne.’ ”

“It must be one of those German prints, it’s so clear.”

From the Arlésienne his eyes moved along the line of bookcases reaching halfway up the wall, across the door, past more bookcases and around the corner to a modern oil painting of a Quebec village in winter, all sunlight and color and with a radiance which made him think of his own Algoma Hills in Ontario. Walls, furniture and rug were all light and neutral in tone; Marc liked their room so much that he knew he would like the Drakes when he got to know them. Apart from all the strangers clustered in groups which were constantly breaking up and re-forming as some of them drifted out into the hall and the dining-room beyond, and others drifted back again, and apart from the fact that he would be stranded again with no one to talk to as soon as Madeleine left, he was beginning to feel quite at home. More at home than he had ever felt in the bleak rooming house for Jewish students where he had continued to live from a combination of inertia and indifference to his own comfort, ever since he had arrived in Montreal to go to law school thirteen years before. The rooming house was large and dusty, with high ceilings, buff walls trimmed with chocolate-brown like an institution, and uncomfortable, leather-covered furniture; during the college term it was so noisy that he usually worked in his office downtown at night, and during holidays it was like a graveyard. About twice a year the place got on his nerves and he determined to do something about it, but after spending several evenings looking at other rooming houses which were worse, and apartments which were not much better and had the added disadvantage of having to be kept clean some way or other, he always gave up and went on living where he was. Now it was no longer worth-while moving in any case, since he would be going overseas in a short time.

“It’s nice to be in a house again,” he said to Madeleine. “Most of the people I know live in apartments. I was brought up in a house.”

Out in the hall, Madeleine’s brother, René de Sevigny, was starting his fourth cocktail, while waiting for Erica to return from the kitchen. He was about Marc’s age but looked older, with dark hair, an aquiline nose, and fine, highly arched eyebrows which gave him a slightly satanic expression. At the moment he was leaning against the staircase with his long legs crossed, staring thoughtfully into his Martini and doing his best to overhear as much as possible of a conversation between two men and a woman in the doorway leading to the library. They were obviously English Canadians, not necessarily because they were speaking English, but because they had devoted most of the past quarter hour to a discussion of Quebec and the war in language extremely unflattering to French Canadians.

“I don’t understand them,” said the woman, who was wearing a red hat, which, René had already decided, would have looked much better on Erica, who was several inches taller, a great deal thinner and who had hair which was naturally blonde. Except, thought René, sighing inwardly, that Erica took no interest in hats, even very chic red hats with coq feathers; she never wore one except in winter or on the regrettably rare occasions when she went to church. “Surely they must know that the war is going to be won or lost in Europe and the Pacific, so why all this ridiculous talk about being perfectly willing to fight for Canada provided they can stay on Canadian soil?”

“Because they don’t want to fight for Canada,” said the man on the right, yawning.

The man on the left was a young officer with a good-looking, but not particularly intelligent face. What he lacked in intelligence however, René realized, he made up in prejudice, and he now rendered judgment. “I’ll tell you what’s at the bottom of it,” he said. “Quebec knows that the war isn’t going to be lost if they don’t fight. But, on the other hand, if enough English Canadians make suckers of themselves and get killed, then the French who had enough sense to stay home will be that much nearer a majority when it’s over.”

“Tiens,” observed René admiringly to himself. “Now why didn’t I think of that? Eric!”

“Yes?”

“Wait for me.” He caught up with her just inside the drawing-room door and asked, “By the way, where’s your father?”

“Upstairs in his study. He always gives up after the first half-hour.”

“Have you seen Chambrun?”

“Who on earth is Chambrun?” asked Erica, taking advantage of the pause to sit on the arm of a chair for a moment. She was one of the few women René had ever seen who could wear her hair almost to her shoulders and still look smart. Seven years of working on a newspaper with erratic hours had given Erica a strong preference for tailored clothes; she wore her fine, well-made suits on all possible occasions and on some which, like the recent large, and very formal wedding of one of his innumerable cousins, to René were definitely not possible.

“He’s just arrived from Mexico—escaped from France two years ago on a coal boat.”

“Why must it always be a coal boat?” inquired Erica, closing her eyes.

“He’s a de Gaullist. I think he hopes to do propaganda in Quebec for the Free French.”

“What an optimist,” said Erica, and then asked hastily, “Friend of yours?”

“Well,” said René cautiously, “I’ve met him a couple of times.”

“Don’t tell me you’re committing yourself to something. . . .”

“Certainly not,” said René, looking amused. “Your mother knows him and said she was going to invite him today. I just thought you might have seen him around somewhere,” he added with a vague gesture which included the drawing-room, the hall, the dining-room and the library.

“Maybe he’s hiding,” suggested Erica.

“Are you asleep?”

“Practically.” She opened her green eyes wide, blinked, gave her head a shake, and asked, “What does he look like?”

“Like a Michelin tire with a drooping black mustache,” answered René, after due consideration.

“Oh, there are dozens of those running in and out of the woodwork in the dining-room,” said Erica. “You might go and see if one of them is your Free Frenchman—and bring me a drink, will you, René?”

“Rye and water?”

“Yes, please. You haven’t got a ‘Do Not Disturb’ sign on you anywhere, have you?” He shook his head and she said sadly, “I was afraid you hadn’t.”

She stood up for a moment when René had gone, looking over the room to see if everyone had drinks and someone to talk to, then collapsed into the chair with her legs straight out, and closed her eyes again.

She was aroused a minute later by her mother’s voice saying, “Oh, there you are, Erica. I’ve hardly seen you since you came in. I’m so glad you were able to get away in time for the party, darling.”

“I have to go back to the office after dinner,” said Erica, yawning. “Special Red Cross story—they sent us the dope but the morning papers will use it as it is, so we’ll have to re-write. After that there’s a Guild meeting.”

“I didn’t know you’d joined the Guild,” said her mother, looking startled.

“I joined last month, as soon as they really began organizing.”

“Why?”

“Partly on general principles and partly because Pansy Prescott fired Tom Mitchell after he’d been on the Post for ten years, because he went on a five-day drunk after his wife died of T.B. up at Ste. Agathe.”

“Well, I suppose . . .”

“It wasn’t just because of the bat,” interrupted Erica. “Or because Pansy doesn’t like women interfering with his arrangements, even indirectly after they’re dead—it was mostly because Tom was the chief organizer for the Guild. I thought if Tom could stick his neck out, so could I. The Post is all for unions provided their employees don’t join any,” she explained. “They have to put up with the linotype operators and the . . .”

“Mr. Prescott will object to your joining, then, won’t he?”

“You bet,” said Erica placidly.

“When I was your age, I didn’t even know men like that existed!” remarked her mother irrelevantly. In appearance, although not in temperament or in outlook, she and her daughter were very alike. They were about the same height, and Margaret Drake was still slender, with light brown hair which had once been even fairer than Erica’s and which she wore rather short and waved close to her head. She was intelligent, practical and unusually efficient, born and bred in the Puritan tradition. She had very definite and inelastic convictions and had had the character to live up to them, and yet you could see in her face that somehow, it had not come out quite right, although she herself was largely unaware of it, consciously at any rate. She never realized that the expression at the back of her blue eyes did not quite bear out what she said with such certainty and so little room for argument; it never occurred to her that there could be anything wrong with her system, but only, on the rare occasions when she had the time, and the still rarer occasions when she had the inclination to think about Margaret Drake, that there must be something wrong with herself.

“You didn’t know Mr. Prescott,” said Erica.

“It seems funny to think of your joining a union. The Guild is a union, isn’t it?”

“Oh, yes, it’s a union. Or it will be someday if the Post doesn’t fire us all first.”

Her mother glanced over the room, remarking absently, “I’m glad you got home in time, Eric,” and then remembering that she had said it before, she added, “I wouldn’t know how to give a party without you any more. You don’t know how much it means to Charles and me just to—just to have you around,” she said, smiling down at Erica. “All the same, you can’t spend the rest of the afternoon in that chair. Get up and be useful, darling.”

“Where shall I start?” asked Erica without much enthusiasm.

“Start by doing something about that young man over there by the window. Madeleine was talking to him a while ago, but she seems to have disappeared.”

“Who is he?”

“I don’t know. He looks like the one René phoned about. His name sounded foreign so I suppose he’s a refugee.”

“I don’t think René knows any refugees,” said Erica.

“Well, do something about him, Eric!”

“All right,” said Erica, struggling to her feet.

The strange young refugee was tall and very slender except for his shoulders; he had slanting greenish eyes, high cheekbones, a square jaw, and to Erica, looked more Austrian than anything else.

She said, “Hello, I’m Erica—one of the invisible Drakes. I’m afraid I got home rather late. . . .”

“My name’s Marc Reiser,” he said, shaking hands.

“Austrian?”

“Native product,” said Marc.

“Oh, Reiser—of course, you’re René’s friend, he’s often talked about you.” She sat down on the window-seat and inquired, “Have you seen René recently?”

“Not since he disappeared half an hour ago.”

“That’s what I thought,” said Erica. “How long have you been standing here?”

“Well, I . . .”

“And of course he didn’t bother to introduce you to anyone, he never does.” She said, looking amused, “Once he deserted me in the middle of an enormous party, all French Canadians, where I didn’t know anyone, even my hostess. . . .”

“What did you do?” asked Marc with interest.

“I just left. I don’t think anyone would have noticed if René hadn’t come to a couple of hours later and started running around in circles wanting to know where I was. I refused to phone and apologize next day, so he had to, because they were rather important people and he’d made quite a fuss about bringing me. Now, whenever we go anywhere, he’s scared to take his eyes off me, for fear I’ll do it again. Wouldn’t you like a drink?”

“Not if you have to go and get it. I’ve spent most of the past half hour trying to look like a piece of furniture and all I want is not to be left alone.”

“All right, then, I won’t leave you if I can help it,” said Erica, smiling up at him.

There was a pause, during which he looked back at her with a curious directness, and finally he said, “This is an awfully nice room. . . .”

“Yes, it—it is, isn’t it?” said Erica lamely. Something in the way he had looked at her had thrown her slightly off balance. He was leaning against the window-frame, half-turned away from her, with his eyes back at the Van Gogh print over the fireplace again, and after another pause she asked, “You’re a lawyer, aren’t you?”

“Yes. I’m with Maresch and Aaronson. I was articled to Mr. Aaronson in my first year at law school and I’ve been there ever since.”

“What about Mr. Maresch?”

“He’s dead.” Marc glanced at her and then said quickly, “I’m not doing much law at the moment, I’m just sort of hanging around at Divisional Headquarters waiting for my unit to be sent overseas.”

“Army?”

“Yes, reinforcements for the first battalion of the Gatineau Rifles—unfortunately,” he added.

“Why unfortunately?”

“We’ve just been pigeonholed for the time being, apparently. It doesn’t look as though the first battalion is going to need us until they go into action somewhere. They’ve been sitting in England for almost three years doing nothing.”

The naval officer and his wife were coming toward them and Erica got up to say good-by. When they had gone, she remarked, “I didn’t introduce you, because I never have seen any sense in it when people are just leaving.”

“Cigarette?” asked Marc.

“Yes, thanks.”

He felt through his pockets and finally produced a folder containing one match. As he held the flame to the end of her cigarette he said, “Your father isn’t here today, is he?”

“He was here for a while at the beginning and then he evaporated. He always does. It’s not shyness, exactly; he’s just not interested in people in general, he’s a rugged individualist. It’s Mother who keeps up the social end of things. Charles can’t be bothered, except at his club. Why? Do you know him?”

“I’ve seen him once or twice, I’ve never met him.”

“If you’d like to meet him, I’ll take you up to his study and introduce you to him. . . .”

“Oh, no thanks,” said Marc hastily. “I’m sorry,” he added, rather embarrassed, “I didn’t mean to sound rude, but I’m no good at meeting people, I never know what to say to them. The idea of barging in on your father just . . . well, I’d rather not, if you don’t mind.”

Erica was looking up at him with interest. Finally she remarked involuntarily, “You and René are not a bit alike. . . .”

“Why should we be?”

“You’re one of his best friends, aren’t you?”

“No,” he said, “I don’t think so. I’ve known him for about ten years, but in all that time I doubt if we’ve ever had a really personal conversation. We usually talk law when we’re together. He’s a very good lawyer. . . .”

“Not politics?” interrupted Erica.

“No, not politics,” said Marc. “We stick to law. I suppose he’s told you that he’s going to run in the by-elections. . . .”

“Is he?” asked Erica, surprised. She said with a faintly amused expression: “One of our difficulties is the fact that René refuses to stop being funny about everything that really matters. Probably it’s just as well,” she added reflectively. “I don’t like quarreling with people.”

“René wouldn’t quarrel with you. He’s too good a politician.”

She could see René across the room talking—French, she realized by his gestures and his expression—to Mrs. Oppenheim, the Viennese refugee. Although she was not in love with him, the very sight of him moved her a little, and she said, her voice changing, “René’s not just a good politician. He’s really brilliant, he studied in France, and even though he disapproved of the French, it isn’t as though he’d been stuck in Quebec all his life! He’s an awfully good speaker and he knows what this war’s all about. . . .”

“Does he?” asked Marc.

“Don’t you think he does?”

“I’m not sure,” said Marc noncommittally.

Between the Drakes’ house and the house on the street below, the steep slope was planted with rock gardens, squat pines and cedars, flowers and flowering shrubs, and halfway down there was a cherry tree in blossom. Beyond the cherry tree and the lower houses half hidden by green leaves, the skyscrapers and church spires were turning to gold and the city was full of long blue shadows.

“What a marvelous place to live,” said Marc.

“Wait another hour when the lights are on and it isn’t quite dark. I’ve lived up here all my life and I still haven’t got used to it. I’ve been in love with Montreal ever since I can remember.”

He was watching a ship which was moving slowly up the Lachine Canal, and thinking of Erica, only half-hearing her voice as she went on talking, softly and unselfconsciously as though she had known him for years. She was not only lovely to look at, she was also the sort of person whom you liked and with whom you felt at ease from the first moment. Her character was in her fine, almost delicate face, in the way she talked and listened to what you had to say; there was nothing put on about her and nothing hidden. You could tell at a glance that she had a good brain, that she was generous, interested and highly responsive. Her manner was neither arrogant nor self-deprecating; it was as though she had already come to terms with life and had made a good bargain, asking little on her side, except that she might be herself. She was wearing a gray flannel suit and very little make-up, sitting on the window-seat with the light falling on her long fair hair, and he knew that she had stirred his imagination and that if he never saw her again, he would not forget her entirely.

Erica was staring at René, who, with his shoulders against the mantelpiece, his hands in his pockets and his eyes squinting against the smoke rising from the cigarette in the corner of his mouth, was listening to the talkative Mrs. Oppenheim with a polite expression, but not much interest. She was actually thinking of Marc, however, for there was something not only preoccupied but remote about him, as though he had spent half his life learning how to withdraw into himself and observe the world from a safe distance. He had an unusually fine body and a physical grace which reminded her of her sister Miriam; he was obviously sensitive and very intelligent, and she realized instinctively that his disconcerting remoteness and preoccupation were both a kind of defense. Defense against what?

Another thing that was interesting about him was the structure of his face. High cheekbones usually went with a light skin, but Marc Reiser was rather dark; his eyes were the same greenish mixture as her own but set quite differently, and although he did not look particularly Jewish nor particularly foreign, at the same time, it would have been a shock to discover that his name was Brown, or Thomas.

“Where do you come from?” she asked suddenly.

“From Manchester. It’s in northern Ontario.”

Erica had spent a night in Manchester once, it was on the transcontinental line, but all she could remember was the sweetish smell of rotting lumber down by the docks, the brilliant blue of the lake with the sun cutting across the outer islands from the west, and the magnificent sculptured forms of the Algoma mountains, lying across a stretch of fields and bush behind the town. Of Manchester itself, she had only a hazy recollection of an interminably long main street which looked like all the other main streets of North America—the inevitable collection of groceterias, hardware and drug stores, gas stations, vacant lots, show windows containing approximately ten times too many unrelated objects, soda fountains, airless beer parlors and three-story office buildings.

She made an entirely unsuccessful effort to visualize the obviously civilized individual beside her, against a background of hardware stores, beer parlors and vacant lots, and finally asked, “How on earth did you get there?”

“I was born in Manchester.” He seemed rather proud of it.

“Where were your parents born?”

Marc grinned. He said, “You remind me of the man named Cohen who changed his name to O’Brien and then wanted to change it to Smith, and when the judge asked him why, he said, ‘Because people are always wanting to know what my name was before.’ ” He paused and then told her, “My parents were born in Austria.”

“Oh, that explains it,” said Erica.

“Explains what?”

“When I first saw you I thought you were Austrian. Why did your parents choose Manchester, of all places?”

“Partly because they didn’t want to live in a city, and partly because the Reisers had always been mixed up with lumber in some form or other and my father heard there was a planing mill for sale there. I like it,” he said, looking down at her. “I’d far rather spend the rest of my life in Manchester than in Montreal.”

“Why?”

“Because in a small town you have a chance to do something. You can be . . .” He broke off, searching for the right word, and went on, “You can be effective. I suppose that’s the only criterion of ‘success’ which isn’t somehow associated with the idea of making a lot of money.”

“Aren’t you interested in making a lot of money?” asked Erica, regarding him curiously.

“Not particularly. I wouldn’t know what to do with it.” He paused, looking off down the room, and remarked, “I’d like to make enough out of law to be able to have a farm someday, though.”

“Why?” asked Erica again.

“Because I like horses. I’ve always done a lot of riding, and I like living in the country—not out in the middle of nowhere, of course, but near enough to a town so that I could go in to the office every day. You ask an awful lot of questions.”

He didn’t appear to mind her questions and she said, “It’s the only way to get anything out of you. Besides, if you know what a person wants most, you usually have a pretty good idea what he’s like.”

“What do you want most?”

“Just what every other woman wants,” said Erica. “I’m afraid I’m not very original. What else do you dream about besides horses?”

“That sounds rather Freudian,” said Marc, grinning, and then answered, “Nothing much. I’d like to be able to buy all the books I want and . . .” He paused for thought and added, “Oh, yes. I want a custom-built radio-phonograph with two loud-speakers and a room full of good records.”

“Do you like music too?” asked Erica.

“What do you mean, ‘too’?”

“Never mind,” said Erica. “I was just wondering where you’d been all these years. What kind of music do you like?”

“Almost everything.” He said quickly, “I don’t know anything about it; almost every time I go to a concert or turn on the radio I hear something that I haven’t heard before. I’m still at the beginning stage.”

She told him about her father’s custom-built radio-phonograph and his record library and said, “You must come with René some evening and we’ll play whatever you like. Charles has almost everything from Corelli to Shostakovich.”

Afterwards she was to remember the way his face lit up, and the way he said, “I’d like to awfully, if your father wouldn’t mind.”

And the utter confidence with which she had answered, “Charles wouldn’t mind at all, once he’d recovered from the shock of meeting someone who was really interested. He doesn’t get much encouragement from most of the people we know. Music is all right in its place, of course, but its place is the concert hall, once or twice a month, and Charles has no sense of proportion. He even interrupts bridge games and rushes home from the golf course in order to hear the first North American broadcast of some symphony written by some crazy modern composer, which nobody in their senses would call ‘music’ in any case. I think a lot of our friends feel that it isn’t quite normal or in very good taste, for a man otherwise as sound in his opinions as C. S. Drake to know so damn much about music and take it so seriously.”

She said with amusement, “My father is incapable of being even moderately polite about a bad performance, regardless of how successful it was from a social standpoint.”

“What sort of music does he like?”

“Almost everything, except that, in general, he’s anti-romantic. He has a passion for Bach and the very early composers and for some of the moderns, particularly Mahler.”

“Do you always call him ‘Charles’?” asked Marc.

“Yes. We have a very odd relationship, I guess. We even lunch together downtown once or twice a week, as if we didn’t see enough of each other the rest of the time!”

“How does your mother feel about music?”

“Mother?” said Erica. “Oh, she has far more sense of proportion.”

People were beginning to go. Erica got up and crossed the room to say good-by to someone, and then came back and sat down on the window-seat beside Marc again, hoping that no one else would notice her. Their guests were almost all friends of her mother’s, with the exception of a few who had been friends of Erica’s but who belonged to the period which had come to an end after she went to work on the Post and in whom Erica had gradually lost interest. Unlike her mother, who refused to believe it, she knew that the loss of interest was mutual; it was as disconcerting for them to discover that in any discussion involving politics or economics, Erica was likely to be on the side of Labor, as it was for her to realize that they were not. She had tried to explain it to her mother but it was no use. Margaret Drake had invited some of Erica’s former friends today because she still felt that Erica was being “left out of things” and remained convinced that the mutual lack of interest was partly the product of Erica’s imagination, partly due to a temporary upset in her daughter’s sense of values, and partly due to the fact that Erica simply would not make any real effort to see them.

Having done her duty and made the rounds before she had discovered Marc, Erica had no intention of moving again if she could help it, at least until the general exodus got under way. No one else in the still crowded room showed any sign of being about to leave, and she turned to Marc, who was still leaning with one shoulder against the wall looking down at her, having watched her all the way across the room and back again with an expression which told her nothing except that he was as absorbed and as oblivious to everyone else as she was herself, and asked, “What did you mean a while ago when you said you didn’t want to go on living in Montreal indefinitely, because you couldn’t be ‘effective’?”

“I meant that I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life in a place where no matter how bad social conditions are, I can’t change anything.”

He paused and then said, “I don’t know whether I can explain it or not,” wondering if she realized that he had never even tried to explain it to anyone else. “It’s this feeling of being completely helpless, of having to watch people suffer, through a combination of bigotry and stupidity and sheer backwardness, without ever being able to do anything about it.”

His eyes left her face and looking out over the city again, he remarked, “I don’t know which is worse, the feeling of not knowing what’s going on behind all the barred windows and high walls of these so-called ‘welfare’ institutions run by the Church, or the feeling that it wouldn’t make any difference if you did. You’re up against a colossal organization that interferes everywhere, in the life of its own people, but which must never be interfered with—even by its own people. In its treatment of the poor and the sick, of orphans, illegitimate children, juvenile delinquents, adolescent and women prisoners, unmarried mothers, and in fact almost everyone who gets into trouble—it is responsible to no one and nothing but itself. What it chooses to tell you about the way it deals with these people, you are permitted to know; what it does not choose to tell you, is none of your business. And of course, if you’re not a Catholic, it’s none of your business anyhow.”

His oblique, greenish eyes came back to her face and he said, “I suppose it all boils down to the one question of just how you want to live, or what you think you’re living for. You can make a lot of money in Montreal, you can be a big success, but you can’t change anything outside your own little racial category. You have to adjust your conscience so that it doesn’t function, except in relation to people who bear the same label as you do, and then spend most of your life passing by on the other side of the road, minding your own business.”

She could not think of any way of telling him that she knew what he was talking about, because he was talking from the same point of view as her own. Instead, she looked up at him and smiled, and then realized that there was no need to tell him. He already knew.

Marc offered her another cigarette, then found he was out of matches and as Erica started up to get them, he said quickly, “No, I’ll do it. If you go, someone else will stop you and start telling you the story of his life. Where are they?”

“Over there on that little table at the end of the sofa.”

Her eyes followed him as he made his way through the groups of people toward the fireplace, and she said to herself that he would stop to look at the Arlésienne. He did.

When he returned with the matches she asked him where he lived.

“In a rooming house on Sherbrooke Street.”

“Is it a nice one?”

“No, it’s awful. You don’t know where I could get a furnished apartment, more or less central, on a month-to-month lease, do you?”

“Well, there’s that new building on Côte des Neiges. I don’t know whether it’s open yet or not—I think it’s called ‘The Terrace.’ ”

“I know, I’ve been there.”

“Didn’t they have any vacancies?”

“Yes, they did have then, but the janitor told me they don’t take Jews.”

He said it so matter-of-factly that Erica almost missed it, and then it was as though it had caught her full in the face. There was an interval during which she was simply taken aback, and then she looked up at him, her expression slowly changing, and found that he had begun to draw away from her, to recede further and further into the back of her mind until finally she no longer saw him at all. He said something else which she did not even hear; she was listening to other voices repeating phrases and statements which she had heard all her life without paying much attention, because they had been said so often before and were so tiresomely unoriginal, but which had abruptly become significant, like a collection of firearms which have been hanging on the wall for years unnoticed, and then are suddenly discovered to be fully loaded.

The voices were talking against a background of signs which she had seen in newspaper advertisements, on hotels, beaches, golf courses, apartment houses, clubs and the little restaurants for skiers in the Laurentians, an endless stream of signs which, apparently, might just as well have been written in another language, referring to human beings in another country, for until now she had never bothered to read them.

She had met a good many Jews before Marc, but in some way which already seemed to her inexplicable, she had neglected to relate the general situation with any one individual. Evidently some small and yet vital part of the machinery of her thought had failed to work until this moment, or worse still, she might have defeated its efforts to function by taking refuge in the comfortable delusion that even if these prejudices and restrictions were actually in effective operation, they would only be applied against—well, against what is usually designated as “the more undesirable type of Jew.” In other words, against people who more or less deserved it.

Now she saw for the first time that it was the label, not the man, that mattered. And even if it had been the man, there was still the good old get-out, “Yes, so-and-so’s all right, the very best type of Jew, and we’ve nothing against him personally, but first thing you know, he’ll be wanting to bring in his friends.” And so “the best type of Jew” was thereby disposed of.

That human beings, regardless of their own merit, should take upon themselves the right to judge a whole group of men, women and children, arbitrarily assembled according to a largely meaningless set of definitions, was evil enough; that there should not even be a judgment, was intolerable.

It made no difference what Marc was like; he could still be told by janitors that they didn’t take Jews, before the door was slammed in his face.

“Hello,” said Marc. He smiled at her, then the smile faded. He stared at her, straightening up so that he was no longer leaning against the window-frame, without taking his eyes from her face, and then he said with an undercurrent of desperation in his voice, “You did realize I was Jewish, didn’t you?”

“Yes, of course,” said Erica, appalled. “Of course I did!”

“I’m sorry, I thought . . .”

“Yes,” said Erica. “Well, you thought wrong. If you’ll sit down, I’ll try and explain it to you.”

He sat down beside her on the window-seat and after a pause she went on, “You see, the trouble with me is that I’m just like everybody else—I don’t realize what something really means until it suddenly walks up and hits me between the eyes. I can be quite convinced intellectually that a situation is wrong, but it’s still an academic question which doesn’t really affect me personally, until, for some reason or other, it starts coming at me through my emotions as well. It isn’t enough to think, you have to feel. . . .”

“I see,” said Marc, as Erica stopped abruptly, somewhat embarrassed. He took her hand without thinking and held it for a moment, then remembered where he was and quickly let it go again, remarking, also embarrassed, “That makes us even.”

Erica laughed and said, “You’re very tactful, anyhow.”

“I wasn’t being tactful.”

“How long have we known each other?” asked Erica, after a pause.

“What difference does it make?” He glanced at his watch and remarked, “Three quarters of an hour. You’re very honest, aren’t you?”

“It seems to me my honesty is rather belated. Anyhow,” she said, smiling at him, “if I never meet you again, Mr. Reiser, you’ll still have done me a lot of good.”

“You can’t call me Mr. Reiser when I’ve just been holding your hand. And what makes you think you’re not going to see me again? You’ve already invited me to come and listen to your father’s records,” he pointed out, and then asked, “What do you do on the Post?”

“I’m the Woman’s Editor—you know, social stuff, fashions, women’s interests, meetings, charities, and now all the rules, regulations and hand-outs from the Wartime Prices and Trade Board that have to do with clothes, house furnishings, food, conservation of materials—that sort of thing.”

“How many pages?”

“Three or four, usually. Depends on which edition it is. I have an awfully good assistant, a girl named Sylvia Arnold from Ottawa, and an office boy named Weathersby Canning, known as ‘Bubbles.’ ”

“Is he any relation to the stock-broking Cannings?”

“Yes, he’s one of their sons—younger brother of the one who got the D.F.C. in April. ‘Bubbles’ is waiting to get into the Air Force too; he’s got another year to go before he’s old enough.”

“Do you like your job?”

Erica paused, and said finally, “Yes. I like working on a newspaper because I like people, particularly newspaper people, but I’m not a career woman, if that’s what you mean.”

She broke off as René appeared, sauntering toward them with a glass in either hand. He asked, “Is there room for me to sit down?” and then remarked, glancing from one to the other, “I see you’ve met each other. Do I have to give him my drink?” he asked Erica as he lowered himself to the window-seat beside her.

“It’s about time you did something for him besides leave him alone. I thought you were drinking Martinis, René. . . .”

“I was,” said René.

“Then stick to them,” advised Erica, removing the glasses and handing one to Marc. “How do you like Mrs. Oppenheim?”