7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Eye Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

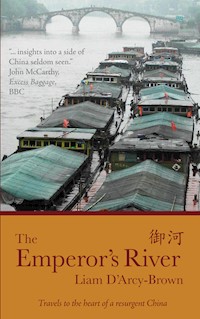

A look China's recent cultural reinterpretation of the oldest canal in the world, dug when Confucius was alive, along which has traveled not only cargo but ideas, customs, and dialects The face of modern China is changing. Liam D'Arcy-Brown travels the length of the Grand Canal, a symbol of national identity, Chinese pride, and cultural achievement. For those with an interest in China and its culture, people, or heritage, this book provides an exciting, fascinating, and well-written account of the navigation of the lifeblood of a rising powerâ€"the Grand Canal of China. At more than 1,100 miles long, and dating back to the 5th century BC, the Grand Canal of China is the world's longest artificial waterway and its oldest working canal. Though a source of great national pride to the Chinese, one of China's most economically important transport routes, and the possible savior of a rapidly desiccating Beijing, it has never been investigated by foreign writers and travelers. The first non-Chinese to have made this journey since the 1780s, Liam D'Arcy-Brown traveled from Hangzhou to Beijing along the Grand Canal by barges, boats, and road and here tells his tales.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

First published in Great Britain in 2010

by Eye Books Ltd

29 Barrow Street

Much Wenlock

Shropshire

TF13 6EN

www.eye-books.com

Copyright © 2010 Liam D’Arcy-Brown

Map by Lee-wan Jon

Cover design by Emily Atkins

Text layout by Helen Steer

The moral right of the Author to be identified as the author of the work has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-903070-70-3

Contents

Title Page

Map

Prologue

The Grandest of Canals

A Culture to be Proud of

Graffiti

Life’s Bitterness

Predictions of Change

Water, but no Boats

A Canal Reborn

Appendix & Author’s Note

About the Author

Prologue

When they were small our distant grandparents were terrified by tales of a skeletal French emperor called Boney, while across the Channel in France le Croque-mitaine skulked under the bed, ready to gobble up any child who misbehaved. The bogeyman still haunts children’s imaginations. But if ever there was a figure calculated to strike fear into young hearts it was Ma the Barbarous, a cruel mandarin of seventh-century China who was said to eat the flesh of infants. It’s rumoured that in parts of China to this day bad little boys are reminded of Ma’s taste for children, a craving so voracious that families with young sons once built boxes of wood bound with iron and each night locked them inside to keep them from his clutches.

But Ma the Barbarous was not just a mythical ogre. In real life Ma Shumou had been a civil servant under Emperor Yang – ruler of what proved to be the cruel and short-lived Sui dynasty – tasked with the job of digging a great canal from the Yellow River to the southern city of Hangzhou. Such a responsibility was not to be taken lightly: already the emperor had commanded that any mandarin who opposed the project was to be beheaded. A levy was made of all men aged fifteen to fifty, and any who went into hiding were executed along with their entire family to the third generation. By such gentle means of persuasion, 3,600,000 labourers were swiftly raised.

Excavating a canal across the marshlands of eastern China proved an onerous job, and the greater part of Ma’s workers were to die before it was complete. Exposed daily to the elements, even Ma himself became ill. His physician made a diagnosis: damp air had become trapped beneath his skin. The remedy, lamb fat mixed with almonds and herbs and cooked in the animal’s breast cavity, turned out to be so efficacious, so delicious, that what had begun as a cure became a preference. Those who wished to influence Ma had the dish prepared and offered up to him. Had matters ended there, Ma might have been remembered as a gourmand rather than a monster.

It was at this point that two wicked brothers, hearing that Ma’s canal was set to destroy their family tombs, murdered a young boy and cooked his dismembered torso in place of a lamb. The dish was even more delicious than before! As rumours circulated of Ma’s taste for child flesh, others who hoped to spare their own tombs began to kidnap boys for him to eat. Unfortunately, the effect of avoiding so many burial grounds was a canal with many unnavigable twists and turns, as Emperor Yang soon discovered when his magnificent dragon boats became grounded upon a shoal. Ma Shumou had made him look a fool, and for this most unforgivable of crimes he was chopped in two at the waist on the bank of the canal he had dug.

How far Ma deserves his gruesome reputation we cannot know, but what we are left with for certain is his legacy. His canal still exists, though its course was realigned long ago to serve Beijing, the capital city of the People’s Republic. Known as the Grand Canal of China, it stretches farther than the distance from London to Tunis or from New York to Miami. It is mankind’s oldest working canal: when Ma’s labourers started work at the dawn of the seventh century they often found themselves redigging even earlier channels cut with Iron-Age tools while Confucius himself was alive. Its very existence has shifted the centre of gravity of a whole nation. It has determined China’s history, its cargoes guaranteeing the power of the imperial elite. It has decided the fate of dynasties, and has dictated the site of the Chinese capital for much of the last millennium.

Today the Grand Canal means business. Two hundred and sixty million tons of freight pass along it each year, two-thirds the volume of the USA’s entire waterborne freight and three times more than Britain’s railway network carries. One hundred thousand vessels ply their trades upon it, and more than 100 million souls pass their lives along its banks. Since the start of Deng Xiaoping’s reforms in the late 1970s, the Grand Canal has been fuelling China’s economy. And if the Communist Party has its way, it might soon be the saviour of a country slowly dying of thirst as the earth’s climate changes.

Just as parents have always told their children stories, so too have nations. The stories of how we came to be who we are give us a comforting sense of identity. In recent years the Chinese have begun to tell themselves a story about their Grand Canal, a story that merges a rediscovered pride in their heritage with a boisterous – and often worrying – nationalism. The course that China chooses to navigate will go a long way to defining all our futures. We should listen to this new story that China is telling itself, and try to understand why.

The Grandest of Canals

from Hangzhou to the town of Tangqi

Cradling the city of Hangzhou in one of her broad sweeps, the Qiantang River breathes serenely in and out. Already that morning she had inhaled a huge sigh of water, the world’s largest tidal bore, deep into her lungs, and now a high tide lapped against her river walls. On her northern shore a mouth opened into that dangerous tideway. Willows shaded a pathway damp with brackish spray. There a scarlet pavilion, its roof like the capital “A” on a thousand-mile manuscript, marked the start of the Grand Canal of China. The confluence of these two waterways was more peaceful than I had imagined it would be, for the Qiantang was wide and the sound of her shipping simply dispersed into the vastness of the heavens. The buildings on the far bank shimmered through a mile of haze. A lone barge waited as the lockgates opened. It was a giant, its length hard to judge. One hundred and forty, one hundred and fifty feet long? The monstrous shiplock swallowed it whole with a silent gulp.

I took out a pen and made a rough calculation on the back of one hand. Beijing lay 1,115 miles away, and the canal here at its mouth was easily 50 yards across. Even assuming a minimal depth of twelve feet to float such great barges, 294 million cubic yards of spoil must have been excavated. But I had seen photographs of the canal further inland, where it could not have been less than three times as wide, and in places it was said to be eight yards deep. Those larger dimensions came to a staggering 2.4 billion cubic yards in total and left the back of my hand more ink than flesh. The two figures averaged out at 1.3 billion cubic yards. Scholars of the Great Wall had estimated that it had taken 236 million cubic yards of rammed earth to build. Even at a conservative estimate, the Grand Canal was far and away the greater achievement. It was only the conspicuous proof of the labour that had gone into the Great Wall, redoubled by its photogenic beauty and the wildness of its terrain, that had made it the more popular of those two siblings, the extrovert yang to the canal’s introverted yin.

For the moment, there in Sanbao Village, the Grand Canal of China was just a meek expanse of water. A string of coal barges was hitched like spent horses to the walls beyond the lock. There was chatter and laughter in their wheelhouses. The canal around them was motionless, ink-black with the run-off from a coal wharf. It skulked low that day as if condensed to liquid carbon by the heat of late spring. Then the ribbon of water turned west with the towpath, and factory walls became columns of pretty willows. I began to see other people out walking, watched cars slide along wide avenues, heard the babble of tourists aboard the shiny, new water buses. Hangzhou had become a modern city in the fifteen years since my last visit, a perky informality of apartment blocks. In the centre of town the temperature dropped so suddenly that passers-by looked up to the heavens as one and shivered. The sky, pregnant and lowering, began to spit. I hailed a taxi: a short drive away, a traditional waterside neighbourhood was rumoured to have survived the frenzy of reconstruction.

By the time our car reached Lishui Road the rain had strengthened. The driver turned his meter off while we waited for the worst to pass, more interested in spending the time in conversation than in charging the extra fare he was entitled to. He pointed to his licence, glued to the dashboard.

“My name’s Cong Bian. Are you married?” I told him I had married just a week earlier. “I congratulate you! I’m married too, with a daughter, ten years old. She’s living in Harbin while my wife and I are here working.” So he wasn’t from these parts? He waved his palm stiffly. “I’m from Heilongjiang. Can’t you hear?” He spoke, now I paid attention, the crisply correct Mandarin of a Manchurian.

“So you don’t understand the locals?”

“They speak Wu dialect. I can understand a little, after two years here, if they speak slowly.” I too found the speech of eastern China incomprehensible, I admitted: the disparate tongues that go under the name of Wu dialect are unintelligible to Mandarin speakers just as Spanish is to an Italian or a Frenchman.

“We’re both in the same boat in that regard”, he mused. “In China we might say we are tong shi tianya lunluo ren – two vagrants thrown together under the same corner of the sky.

“We moved down here to the coast after I lost my job,” he explained. “I’d worked in a factory, but the economic conditions in the northeast are poor. We’ve entrusted our daughter to her grandparents. This is the only way to earn money to put her through school, to save for our parents’ old age, for our own retirement.” But he did not want to talk about his old life in Manchuria, as though it pained him to be separated from his flesh and blood. The rain was easing off. Wiping away the condensation from a window he looked intently at our surroundings and changed the subject.

“This is Grand Canal Cultural Square, where the authorities have built the Grand Canal Museum. It’s cost the city more than 100 million renminbi. Over there is Bowing to the Emperor Bridge. Very beautiful.” Where were the old warehouses, the inns, the wharves and landing stages that had once stood where now there was an open plaza? “Chaichule,” Cong Bian shrugged. “Demolished.” He read my look of disappointment, and quickly added in consolation: “But Bowing to the Emperor Bridge is very old, the oldest structure in Hangzhou. Ming dynasty.”

In his former life he had been an unskilled worker, and in his industrial hometown there was nothing so old, he said, or so enchanting. The bridge’s triple arches soared, its steep granite steps reaching fully 50 feet in height before starting their descent to the far shore a hundred yards away. It was undeniably beautiful, even in rain that fell like water spilling from a calabash ladle (as the Chinese phrase has it), the last echo of the dozens which had once spanned the city’s waterways. We both stared in appreciative silence at this reminder of how lovely China could be. On the misted windscreen Cong Bian drew two thoughtful strokes with a forefinger, the second running off at a broad angle from the first. They formed the character ren: human.

“I remember how in the 1980s, just as we were beginning to rediscover our history after the Cultural Revolution, state television broadcast a long series of programmes on the canal. The first was called Two Strokes of the Writing Brush. I still remember sitting as a child in front of a TV in my parents’ work unit – they worked in a chassis factory – watching a man in a suit with a great map of China on the wall behind him. ‘This first stroke, here,’ he said, ‘is the Great Wall. And this one is the Grand Canal. Here, where the two lines join, is Beijing, our capital.’ The very character for ‘human’, you know, reminds us of what the Great Wall and the Grand Canal look like on a map of the People’s Republic. You understand, we Chinese built that wall, dug this canal, brought human civilization to this land with our bare hands.”

The rain eased, and soon we had said goodbye. The museum proved to be closed that day. Standing alone upon the bridge’s crown, the water far below was still, betraying its slow drift only by the chemical which bled scarlet-red from a drain. Then, as that stain merged into the ripples, the blunt nose of a barge appeared beneath my feet. Her hold followed, sliding gracefully upstream with a cargo of gravel, and presently there came her wheelhouse. Behind her the dull dishwater became a wake of white foam. As the barge’s bulk raised a bow wave from the meagre depths, the canal sucked at its own shallows to bring clouds of mud billowing to the surface like liquid smoke.

*****

So old are China’s canals that their origins fade into fables. The oldest is the legend of the folk hero Yu the Great, who calmed the flood that once inundated the world. Yu dug and dredged for thirteen years, channelling the water out to sea and refusing to return home to rest despite the birth of his son and heir. That legend is known to all Chinese, for Yu’s mass mobilization of Bronze-Age farmers can be seen as the true starting point of Chinese civilization. It is a civilization built upon a profound understanding of water and how to control it, as an unforgiving environment forced ingenuity upon the earliest ancestors.

For the pattern of rainfall in northern China was always intensely seasonal, with summer monsoons that filled watercourses to bursting and dry winters that tested the skills of reservoir builders. “Picks and shovels are as good as clouds, and opening a channel is as good as rain”, goes one age-old saying. Running through the birthplace of Chinese civilization, the Yellow River was ever a capricious creature, her water bearing a staggering load of silt which raised her bed and choked her path, causing devastating floods. Even in the wetter Yangtze valley, where later generations would learn to cultivate paddy, water had to be stored and released through laboriously maintained works to ensure that rice seedlings had all the moisture they demanded at just the right points in their life cycle.

The Chinese proved more than capable of controlling that challenging environment, and with good husbandry the plains of the Yellow and the Yangtze became amongst the most densely populated places on earth. Kings and emperors mobilized millions to share in the work of flood prevention; ditches were dug to draw water into the fields, deeper channels cut to connect these to the great rivers. Long, long before China was ever a unified nation, junks were sailing out across those lands upon a labyrinth of man-made waterways.

The Grand Canal became the greatest of them all, and Hangzhou at its southern terminus one of the richest cities not just in China but on earth, its populace so large, so wealthy, that their gowns struck visitors as a solid screen of silk. Its markets were said to be piled high with gold and silver, the masts in its harbour as thick as the teeth of a comb. Flowers that never faded gave the city an air of everlasting spring. Today the West Lake that lies at its heart is one of the most beautiful sights in all China. Pleasure boats glide out from the wharves, and at dusk the locals promenade, or sit in silent embraces. Lined with weeping willows, hemmed in by hills speckled with temples, they have good reason to call it the finest lake in the world. On that first day of my journey I found a bench by the lakeshore and sat deep in thought. I recognized this place from my childhood, as though I had been predestined somehow to be there.

Not long into secondary school, you see, I had read ahead in my French grammar, beyond the present tense and into the past and the pluperfect, so that when my classmates were introduced to avoir and être verbs I was instead dispatched to a store cupboard to translate French pop songs. But my mind wandered from the lyrics of Tous les Garçons et les Filles and I began to potter around shelves piled high with old textbooks. One, Beginning Chinese, was a university primer, half in Romanized script and half in Chinese characters. Upon its cover was a sketch of a lake.

I spent hours poring over that book, copying its characters inexpertly onto the bare walls of a new home, staring into its pen-and-ink illustrations as though awaiting some revelation. In Lesson One a besuited Mr Bai met a friend. Their meeting place overlooked a lake where people took tea on boats, and where a breeze ruffled the willows. A temple nestled in a fold of the hills, and a pagoda stretched up to heaven. Beginning Chinese became my subconscious template for China, a childhood ideal that did passable service for an entire country. It was just eight years later that I visited the People’s Republic for the first time, by then a second-year student of Mandarin, and the image of the lake shrank to become just one element in a growing collage. I returned time and again to visit new parts, studying in Shanghai just as that dazzling city was finding its feet after the torpor of Mao’s command economy. All the sights I saw, all the sounds and all the smells, became a sensual soundtrack to my life. But of all the memories, it was to the cover of Beginning Chinese that my thoughts turned as I sat on that bench in Hangzhou. The illustration had come to life, correct to the last detail as if it had been the artist’s very pattern. I slid into a jetlagged half-sleep. A young man sat down beside me.

“Mr Bai?” I asked dreamily. No, he answered, his surname was not Bai; had I mistaken him for somebody? Yes, I said, I had once come across a Mr Bai in a book, who wore a suit just like his. We talked about my reason for being in China.

“Weishenme?” he asked. “Why? Why this big Grand Canal journey? And why now, at such an important time?”

Yes, it was an important time: only five days earlier I had taken my wedding vows in a church in the English shires. Rebecca and I had been together for ten years, and it had felt right to marry before being parted for several months. A fair-weather traveller raised in temperate York, I wanted to set out after the worst of the spring rains had passed and reach Beijing before August’s heat. Our wedding day turned out to be a beautiful late-April afternoon, but we had spent only four days together before driving to Heathrow. Then Rebecca had had a nosebleed and spotted my shirt with blood, and our goodbyes had been of tender bewilderment.

“Why the Grand Canal?” I repeated distractedly. “Perhaps it would have been better if….” Uncertain, my voice trailed off. Glimpsed from the air the canal region had been a daunting tangle of threads teased out over the plains, each as fragile as a rivulet of rain upon a dirty window. I had taken in its sheer scale and wondered whether I had made the right decision. So why was I here?

It was apparent that the Chinese were increasingly focusing attention on their Grand Canal. With each new website and museum, with the completion of every canal-widening scheme and the founding of preservation societies up and down its length, China was beginning to look at the canal with fresh eyes. The sudden interest hinted at deeper currents, and I wanted to discover what these might be. Besides, just as in Chinese medicine the pulse is the most valuable diagnostic tool so there could hardly be a better place to gauge the state of the nation than upon this artery linking its economic heart to its seat of government.

Hearing of my plans to follow the Grand Canal, friends and relatives had joked and told me how much I would love Venice. Yes, and there were other grand canals – one more in Alsace, yet another in Ireland – but China’s was the very grandest. Why nobody had thought to follow it from source to terminus left me lost for an explanation. Since a gap had first opened in the bamboo curtain, writers had crossed China by train, sailed the Yangtze, bisected the country by road, walked the Great Wall. Only the Grand Canal, inconspicuous behind a workaday façade, remained a missing piece of the Chinese jigsaw. I suspected too that the journey would be a personal challenge, a test of that idealized China I still carried from the cover of Beginning Chinese.

In preparation I had read everything I could find on the canal, a scant library amounting to a few volumes in Mandarin and even less in English. I had pored over atlases, scoured libraries for the faded wayposts of earlier travellers, had memorized a list of nautical terms, but there my knowledge ended. And so, early the next morning, I caught a bus back to the Grand Canal Museum to learn more.

It unfolded like a Chinese fan across Grand Canal Cultural Square, a near semicircle of grey stone. A magnificent frieze swathed one wall in bronze, where slaves strained to haul Emperor Yang’s dragon boats. In the lobby a line of lights snaked across a great map of China. The world’s other great canals were stretched out beside it, even the longest of them a poor second; the Suez and Panama canals combined were less than one-seventh of its length. Then came the text of the Hangzhou Declaration, drawn up by a select group of cadres, academics and dignitaries. It proudly summed up the importance of the canal in Chinese eyes.

“The Grand Canal,” it began, “is a great engineering project created by our nation’s labouring people in ancient times, a precious article of material and spiritual wealth handed down to us by our ancestors, a living, flowing and vital piece of mankind’s heritage.” From its roots in the Spring and Autumn period, the Declaration went on, the canal had become a vital route for waterborne traffic, binding the north to the south and spanning five mighty river systems. Over the course of millennia it had contributed to China’s economic development, to national unity, to social progress. It was proof that China’s ancient technology had outshone other civilizations.

“With her own milk,” another panel waxed lyrical, “the Grand Canal suckles those who dwell on her banks.”

“Because of the Grand Canal we get rich!” boasted another.

The reason for the canal’s existence revealed itself as I ventured deeper into the museum. At its height as many as 18,000 imperial barges had shuttled 600,000 tons of grain – rice, barley, millet and others – to the capital each and every year. In fact the Chinese writing system still has a unique character – cao – which can only adequately be translated as “the annual transport of grain to the capital by water”. It was on that grain that China’s emperors relied for their very survival. They parcelled it out to their kinsmen, paid it as wages to their scholar-officials, used it to sate the bellies of their armies and so buy their loyalty, and to fill the Ever Normal Granaries to guard against famine and rebellion. Each of those strong dynasties familiar from the history books – the Tang, Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing – had been made possible by the Grand Canal. When it was functioning well, the grain flowed and the dynasty was secure; when the grain supply was interrupted through natural disaster or by war, decline was inevitable.

To the peasants who had provided the muscle power and grain for the annual cao, the Grand Canal was a terrible physical burden. Keeping it supplied with water took priority over the crop still in the ground; farmers had to wait until the barges had passed before their field sluices were reopened, and there were harsh punishments for those who tapped even the smallest spring. For others the canal brought unsurpassed riches. Merchantmen bore cargos from the south – porcelains from Jingdezhen, damasks, satins and silks from the Yangtze delta, ornaments of precious metals, carved ivories, pearls, wines, paper, tung oil, ironwares, alum, jadeite and other prized minerals – and the abundance of tropical field and mountain – sugar, liquorice, bananas, areca, tea, hardwoods, bamboo, medicinal herbs, incense. Thousands of tons of Yunnanese copper were delivered each year to the imperial mint. And southward there came in return the produce of temperate northern China, its cotton, wheat, soy, peanuts, sesame oil, pears, jujubes, almonds, melon seeds and walnuts. Like the Londoners who watched the fruits of Empire arrive at their own docks, the Chinese looked on in awe.

“A million dan of millet is carried to the capital,” wrote one fourteenth-century scholar. “Tribute from southeast China, those hundreds of categories of things presented to the emperor which yearly number in the billions, all must cross the Yangtze, the Huai and the Yellow. How innumerable are the objects the people rely on for their daily lives! Goods come and go, nowhere else under Heaven in such numbers. From across the seas come the exotic treasures of distant peoples, their divine horses and strange wares. Some are more than a year on their passage, all flowing along the Grand Canal to arrive beneath the palace watchtowers. This is truly a feat unknown in the annals through all the ages.” With those cargoes travelled ideas, customs, and dialects. Just as importantly as all the grain and silk, the Grand Canal was a force for unifying Chinese culture.

And in the twenty-first century? It is the Grand Canal that is bringing cheap coal to the power stations of the Yangtze delta, the sand, cement and bricks behind the futuristic skyline of Pudong, the tarmac that covers the motorways of wealthy Jiangnan, south of the Yangtze River. If its course dried up overnight, the building sites would be silenced and the lights would soon go out. The roads would be overwhelmed with the task of supplying the essentials of life to Shanghai – overwhelmed, that is, until tanks ran dry and there were no more barges bringing precious fuel. A permanent blockage in the canal would strike the local economy like a heart attack, and its effects would quickly be felt across China and eventually the world. It would be hard to exaggerate its importance to the economic life of the People’s Republic.

In the museum’s final room was hung a summary of its message:

If the Great Wall was the shield that defended our peaceful agricultural civilization, then the Grand Canal made possible the flow of traffic that poured forth into it an exhuberant vitality. Though born of military and political considerations, the Grand Canal has tenaciously manifested an independence of will, playing an immense role in the economic and cultural development of the Chinese people. With so many cities rising up on its banks, how can we see it other than as the Mother River of the Eastern Plains? The rich and profound connotations which it holds for the Chinese people will continue to stir us, to be for our cultural lives an inexhaustible wellspring.

The coming thousand miles would show how true those sentiments were.

The next morning I flung open the door of a taxi to escape the torrential rain. It was Cong Bian from the previous day who greeted me with a smile.

“Lin Jie, I knew it was you standing by the road as soon as I saw you. I told you yesterday that we were both to be found under this same corner of the sky. We’ve got yuanfen.” In a city whose nucleus alone was home to 3,000,000 people and 8,000 taxis, it did seem that we had yuanfen – fate – bringing us together. I told him of my plan to sail to Tangqi, a town a few miles to the northward: there could be no better way to understand the canal and the people who lived upon it. Did he know where I might find a barge? He did.

“Last night I told a friend you were travelling the Grand Canal,” he ventured as we drove through miles of suburban industry, past compounds of boxy concrete. “We talked about you. He said that it’s 1,800 kilometres long. ‘Ta you bing ma?’ he said to me. ‘Is he crazy?’”

Cong Bian did his best to dissuade, to make me stay in Hangzhou and meet his wife, to drink the finest Longjing tea from Lion Peak and eat West Lake fried shrimp. He looked me in the eye. “It’s not as simple as you imagine,” he impressed. “My friend understands these things.”

Sorely tempted by an easy life of tea and seafood, still I jabbed determinedly at the map. Cong Bian shrugged and chuckled. “You foreigners are very curious,” he conceded. “Let’s find you a boat.”

At a lonely wharf, a vessel was taking aboard fuel. She was tied fast to the filling station, itself a retired barge with steel plates welded over its hold. A gangplank gave ungainly access from the quay. Stretched over a frame of rusting pipework was a tarpaulin, and underneath this stood a pump. A woman watched as the counter ticked over, and a man in a grubby two-piece suit squatted on the deck. Cong Bian edged nervously along the gangplank and addressed them. After their greetings I lost the sense of what they were saying: Cong Bian’s adopted dialect was better than he claimed. The bargeman weighed me up.

“Tangqi? Two hundred kuai,” he said decisively. It was no small sum, 40 or 50 times the bus fare, but there was no other barge tied up within sight. “Pay now, before we cast off.”

“We’re a freighter, not a passenger boat,” the woman added. “And you haven’t a sailor’s permit. If the harbour supervisors see we’re carrying passengers we’ll be fined.”

My renminbi went toward the cost of the fuel, and then the hawsers were unhitched and tossed onto the deck. Two engines spluttered into life, the bargeman teased the wheel and opened the throttle, and a satisfying splashing from the stern told that the propellers were tearing at the water. Already ten miles from that scarlet pavilion on the Qiantang River, ahead of me stretched 1,105 more. My landsman’s stomach lurched as the barge swung into the stream.

“Aya, the price of fuel’s higher now than ever,” the woman muttered as she squeezed down the narrow gangway. How high? I asked, when they had both finished sucking their teeth in annoyance.

“It’s more than five kuai a litre now,” the bargeman complained. “And now and again there’s rationing at the pump.” Then he whistled softly at my quick calculation of the price back in England, where a litre of diesel was more than three times what he had just paid. “How do your scrap-metal bargemen make any money?” he asked innocently.

The 021 Cargo – this is all I remember of her name – was typical of the rusty tubs which busied themselves like restless scavengers, foraging at the bottom of the food chain for loads to shuttle from here to there. Try to imagine the antithesis of a brightly painted English narrowboat. Technically speaking she was a welded-steel self-propelled barge, flat-bottomed and double-hulled, most of her deck taken up by a cavernous rectangular hold. Ropes held car tyres close to her flanks, but despite them her ironwork was beaten and sunk from years of minor collisions, her hull so battered that her bulkheads showed through like the ribs of some starving creature. Her wheelhouse was just a makeshift shelter where Mr Yao and his wife took turns on a wooden stool. This faced a tarnished wheel, a throttle, and a few greasy buttons which remained untouched, their purposes obscure. Window panes and doors had been salvaged from somewhere or other and crudely nailed together to keep out the elements. The roof was of chipboard, oilskin-swaddled and lashed down to cleats, and with its bamboo pike-poles, its ropes, mops and buckets the 021 Cargo looked not unlike a scrapyard animated and set afloat. In flowerpots grew an emerald thatch of chives and some bolted garlic, a diminutive vegetable garden for a couple who lived on water. Aft of the wheelhouse a hatch led into a tiny compartment where the Yaos might snatch some sleep. A thin mattress ran the width of that lightless nook. Behind this, inimical to rest, the barge’s twin engines were exposed on the deck. Their bodies had oxidized to white with the heat, their exhausts to a livid red. Cooling water spat with their vibrations, and a pair of hefty flywheels span frantically, transmitting their powerful torque to the propellers.

Miles from that first listless shiplock on the Qiantang the day was growing busy. The other traffic that morning was mostly barge trains, floating convoys lashed together stern-to-bow with steel ropes and pulled by hardy tugs. The 021 Cargo came level with one.

“Yi, er, san, si, wu…” The rest trailed off uncountable into the distance.

“Shi’er sou,” interrupted Mr Yao, guessing what I was doing. “Twelve. They’re from the coalfields of Shandong province, carrying fuel for Hangzhou. There are normally twelve to a train.” Just as he had predicted, a dozen barges slowly passed us by. Their holds were swathed in taut tarpaulin, and traces of coal lingered on their russet decks. “These twelve barges, perhaps 4,000 tons of coal. How many lorries would you need to carry 4,000 tons of coal? Two hundred? It costs perhaps one tenth of the price of road haulage to carry coal by barge to the power stations where it’s needed, perhaps ten or twenty kuai per ton less than transporting it by rail. That makes the electricity cheaper, and the economy more competitive.”

“These must be the very biggest barges?” I commented. He smiled at my naivety.

“Bu, bu, bu. Others carry 1,000 tons each and more….” He talked impassively, as though it were a mere trifle. Before this, my only other experience of canals had been visits to beer gardens set beside rural English locks, of narrowboats designed to carry 30 tons of the Duke of Bridgewater’s coal. These behemoths were a world away from the slim vessels on the Grand Union Canal back home.

The convoy was approaching its distant power station at walking pace, but still the tug’s wake stretched back to envelop the first three barges in a skirt of white. On the barges’ decks the crews smoked, walked back and forth watching the other traffic, or mopped the gangways to pass the time. Children in life jackets played games. The smaller ones, some barely toddlers, were anchored to hitching posts. Mongrels stood sentinel, barking warnings at other vessels.

“You save fuel by buying in to a barge train,” said Mr Yao. “One tug can pull many barges, more slowly than travelling alone, of course, but they’re not in a hurry.”

Like the tiny 021 Cargo, some larger barges too chose to sail alone. Unladen they towered yards above the stream, the waves slapping on their bow rakes as they rode over them, their flat hulls drawing scarcely a foot of water. Others though were dangerously overloaded, their decks submerged and with water lapping against the coamings which protected their holds. A large wave, a glancing collision, might easily swamp them.

“They shouldn’t be sitting that low,” observed Mr Yao in a concerned tone. “Barges like that sometimes sink. People drown. In shallow stretches they can ground and block the way for days.” He steered a course along the right-hand lane, just as he would on a Chinese road. The bank rose beside us like a vertical mosaic, its irregular chunks of granite rough-hewn, now well-pointed, now a confusion prised apart by roots. Mrs Yao returned from the bow where she had stood watching the world go by.

“How many knots are we doing?” I asked, hoping to impress by using the Chinese for “knot” (it is jie, the character for the knuckles on a bamboo stem).

“We don’t talk about ‘knots’ on inland waterways,” she corrected. “We use kilometres per hour. We’re doing about fifteen. We’re limited to seventeen, you see, else the wake damages the banks….” On cue our wake struck the bank and slooshed into the cracks. “… But at this speed we’ll still be in Tangqi in less than two hours.”

For those two hours I sat hypnotized by the grey ribbon unfolding ahead. The city of Hangzhou seemed never to come to a conclusive end but continued in an unbroken sprawl that escorted us north. Factories and homes had unfurled like tendrils colonizing the margins of an endless source of nourishment. In the three decades since Deng Xiaoping had launched China’s economic reforms, this corner of the country had been transformed. The canal pulsated with life, here the narrow channel of Hangzhou, there a broad river wider than the Thames in central London. At such a distance, even the near bank became a blur through the morning drizzle….

“Lin Jie!” Mr Yao called me into the anonymity of the wheelhouse.

“Gangjian,” he explained nervously. We passed a squat watchtower. The Gangjian, Harbour Supervisors, were on the lookout for illegal cargoes, he said, and dangerous loads. We watched the cargoes drift past, all of them heavy but low in value, the kind of freight that made road transport uneconomic: scrap metal, coal, diesel, rolls of steel wire, dredged mud, heaps of sand, gravel and ballast, and orange bricks stacked so neat and so high that they looked from a distance like approaching buildings. They all bore well their rough handling, did not spoil when dumped without ceremony into a gaping hold. There were no more porcelains, no silks or cottons, no tropical fruits and fish for the emperor.

It had been a long time since such exotic cargoes were last carried. At the time of Liberation in 1949 the Grand Canal had been redundant for almost 50 years, superceded by locomotives and ocean-going ships. But what the fragile government of the new People’s Republic needed was not the tax grain, the luxuries and the gewgaws that had propped up old, feudal China, but instead coal to power a command economy, and materials to rebuild a war-ravaged country. The Grand Canal became a priority. Up and down its length, thousands were soon shovelling out the silt of decades, removing sunken boats and tree trunks, uprooting reedbeds. Timeless stone arches were replaced with pre-stressed concrete spans; primeval oxbows were recut and straightened. The Grand Canal faded with the imperial system it had made possible, but it was swiftly resurrected as a life-giving artery of what will soon be the world’s largest economy.

The 021 Cargo hove to outside town, where the chimneys of Tangqi became visible around a sweeping bend. Mr Yao could go no further upon the narrow old canal, and set off instead along a wide, new bypass.

“If I see you again, I’ll cry out,” he promised. After the reunion with Cong Bian the taxi driver, I half suspected we would meet once more.

The rain had stopped. In the centre of town the old canal was empty and unruffled, a mirror for the seamless white of the sky. The Good Works Bridge linked its two banks, hunchbacked, a dark rhombus pierced by seven circles of light. Its age merged into whispers of legends, already old when the English were defending their distant kingdom against Viking invasion. It had withstood the collapse of dynasties, Japanese occupation, civil war, even the vandalism of the Cultural Revolution. Then lumbering barges had struck it and its demolition had been discussed in high places. To the credit of the local Party Committee a bypass had been dug and the bridge spared, renovated as a civic centrepiece. Swallows brushed its marble cheek, swooping and veering to catch mosquitoes. An elderly couple sat in the day’s weak sunshine. Their home was humble, of whitewashed plaster crowned by a sagging jumble of black pottery, a style called fenqiang daiwa – white-powder walls and mascara tiles – as though each like a sing-song girl were presenting a carefully made-up face to the world. This was how I remembered Hangzhou, before urban planners had set about raising the city’s living standards. The only vessel on the canal was a blunt-nosed sampan from which a hunched figure spooned at the water with an oar. Now and then it would reach out with a sieve on a pole to fish a plastic bottle from the ripples. Every twenty would fetch more than enough for a bowl of rice.

A modest hotel on the town square had rooms to spare. Outside, a crowd had stood about laughing and offering advice as two men in leather jackets – bruisers with bull necks, gold chains and pork-pie hats – encouraged their dogs to mate. Any relief at being inside was momentary: there was a rap on the door; two plainclothes policemen were standing in the corridor.

“Mr Lin Jie?” said one. “We need to ask why you’re in Tangqi.”

*****

Tangqi lay only fifteen miles from the luxury hotels that encircled the West Lake, yet it felt as though it might not see a foreign face from year to year. In small towns like this, officialdom still required unexpected visitors to explain their business and register their presence. The owner of this hotel had no licence to accept foreigners and had put in a call to the nearby police station before word got to them by some other route.

The officers arrived in polyester suits and slip-on shoes, the everyday uniform of provincial detective constables. Cigarettes were surgically attached to their fingers. They made themselves comfortable on the bed and drank tea. One produced a sheet of questions: where had I come from? Where was I going next? The answers intrigued him. Why Chongfu? I told them of my plan and, not reflecting on the folly of truthfulness, about the 021 Cargo.

“Your Aliens’ Travel Permit, please.” He held out a hand. “There are no passenger services to Tangqi, you understand. Mr Lin, you can’t undertake a trip like this without first arranging it with the correct work unit and obtaining an Aliens’ Travel Permit. From the visas in your passport you’ve been to China many times before; you ought to know this.”

Of course I knew this: I had criss-crossed much of China with a rucksack and a notepad over the past sixteen years, had travelled to its islands and deserts and to its four most far-flung points. But I had only seldom informed the authorities: making such arrangements was complex, and their forced itineraries were often a suffocating blanket of handshakes and stupefying toasts in hard liquor.

“It’s dangerous to ride these barges. You might be robbed, or drowned. I’ll put ‘bus’ here in this box for your travel to Chongfu, hao ma?” I gave a forced smile of consent, and my immediate itinerary became set. “When you reach Chongfu, remember to register with the police.”

They closed the door behind them. There had been plenty of police launches tied up on the banks that day, and news of a foreigner would quickly filter through. I consoled myself that there were still more than a thousand miles left, only… what if in Chongfu, in Jiaxing, and in every place I wanted to see between here and Beijing it was already being decided in smoke-filled rooms how I could travel? Perhaps I should have done something about this before ever leaving home.

But I was here now, and so in that spartan room I set about planning the progress I hoped to make day by day. The task left the six provincial atlases I had brought along covered in scribbled notes. Along the length of the Grand Canal itself, an unbroken strip of sky blue from Hangzhou to Beijing, I scored lines of daily aspirations, destinations to aim for at fifteen-mile intervals. This done, I turned my attention to what had already been written by travellers who had gone before me.

By the very nature of a canal, millions of men had passed this way. Most were nameless, but amongst them was a handful who had recorded their experiences, and copies of their writings were squeezed into my rucksack. The oldest of them was a scholar-official named Lou Yue. In 1169, with China divided between Jurchen tribesmen in the north and the Southern Song dynasty in the south, the Chinese emperor sent a delegation to the Jurchen to wish their ruler well for the New Year. Lou Yue, secretary to the delegation, submitted his Diary of a Journey to the North to the emperor on his return. Part travelogue, part gazetteer, part espionage, it was rich with detail on conditions under Jurchen rule. Returning south, Lou Yue recorded his experience of the Grand Canal. This though was familiar territory to him and he wrote now as though mindful of the price of ink.

Next came Ch’oe Pu. In 1487 this 33-year-old Korean official had set sail from the island of Jeju for the Korean mainland to bury his late father. Instead, his ship had been tossed onto the coast of Ming China by a storm. Soon he was being escorted northward on the Grand Canal toward the Korean border. His family, he thought, must have assumed him long drowned.