Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Honford Star

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Set in 1940s colonial Korea and Japanese-occupied Manchuria, Endless Blue Sky tells the love story between Korean writer Ilma and Russian dancer Nadia. The novel is both a thrilling melodrama set in glamorous locations that would shortly be tragically ravaged by war, and a bold piece of writing espousing new ideas on love, marriage, and race. Reading this tale of cosmopolitan socialites finding their way in a new world of luxury hotels, racetracks, and cabarets, one gets a sense of the enthusiasm for the future that some felt in Korea at the time. Honford Star's edition of Endless Blue Sky, the first in English, includes an introduction and explanatory notes by translator Steven Capener.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 495

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

praise for endless blue sky

‘Set against the glittering background of 1940s Harbin and Seoul, colonial Korea takes centre stage in this page-turning melodrama. Endless Blue Sky comes with a new vibrancy and presents a new world; utterly pro-European in its ideology and peppered with avant-garde ideas on love and marriage, on success, fulfilment, and happiness.’

—kevin o’rourkeTranslator of Our Twisted Hero by Yi Mun-yol

‘Endless Blue Sky depicts the complex identity and dreams of a colonial Korean traveling to Manchuria to find the West. There, he attempts to overcome his identity as a colonial subject, the influence of the Japanese empire, and the culture of the East. The novel vividly depicts various aspects of East Asia circa 1940; opium addiction, kidnapping, Russian refugees, Harbin dance cabarets, and symphony orchestras. This novel deepened the spatial and cultural imagination of Korean novels in the colonial period, raising issues of globality and locality.’

—lee kyounghoonAssociate Professor, Dept. of Korean Language and Literature, Yonsei University

‘Devotees of Korean literature in English translation tired of reading the same handful of canonical short stories by colonial period writers will welcome Steven Capener’s new annotated translation of Endless Blue Sky. Finally we have another full-length novel available to us in English from this period, and by one of modern Korea’s greatest lyricists and stylists.’

—ross kingProfessor and Head of the Dept. of Asian Studies,The Univeristy of British Columbia

ENDLESS BLUE SKY

a novel by lee hyoseok

Translated and Introduced bysteven d. capener

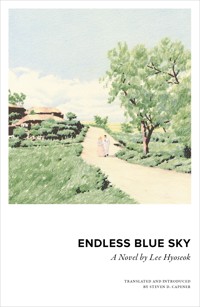

This translation first published by Honford Star 2018honfordstar.comTranslation and Introduction copyright © Steven D. Capener 2018All rights reservedThe moral right of the translator and editors has been asserted.ISBN (paperback): 978-1-9997912-4-7ISBN (ebook): 978-1-9997912-5-4A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.Cover illustration by Lee KyutaeBook cover and interior design by Jon GomezPrinted and bound by TJ InternationalThis book is published with the support of the Literature Translation Institute of Korea (LTI Korea).

INTRODUCTION

Lee Hyoseok was born in 1907 in Pyeongchang, Gangwon province, Korea. He graduated from the prestigious Gyeongseong 1st High School (Now Kyunggi High School) and then entered the English Literature Department of Gyeongseong Imperial University where he distinguished himself, writing his graduation thesis on the Irish poet John Millington Synge. He debuted as a writer while still a college student, publishing ‘The City and the Ghost’ (1927) about the increasing number of homeless people (ghosts) in the city of Seoul. After graduating in 1928, he continued to publish short stories that often depicted characters with socialist leanings, earning him the reputation of a ‘fellow traveller’ writer sympathetic to the socialist cause.

In 1931, he married Lee Gyeongwon, the daughter of a middle-class family. In 1933, he joined the modernist coterie the Group of Nine along with fellow writers Yi Taejun, Park Taewon, and Yi Sang. In 1934, Lee was hired to teach literature at Sungshil Technical College in Pyongyang. He lost both his wife and his youngest son in 1940 and met an untimely death in 1942 at the age of thirty-six.

In the mid-1930s, Lee’s writing moved away from proletarian themes to embrace a distinctly modernist style. His short stories after 1935 were characterized by a lyrical tone and an emphasis on the primacy of nature over human artifice. Works such as ‘Mountains’ and ‘Fields’ are representative of this shift; however, there were two other palpable thematic shifts that accompanied this new natural lyricism: bold depictions of sexuality that were ahead of the times (and which included extra-marital sex and homosexuality) and a privileging of Western (European) high culture.

One of the aspects of Lee’s depictions of sexuality that was extraordinary for the times was that he gave female characters a high degree of sexual agency, depicting them choosing sexual partners for pleasure (‘Bunnyeo’) and fantasizing about homosexual encounters with other female characters (Hwabun). Lee seemed to enjoy turning the tables on the patriarchal mores of Korean society in the 1930s by creating sexually liberated femme fatales such as the one in ‘The Sick Rose’ that gives both of her partners syphilis. Such sexual freedom seemed to be part of a larger desire on Lee’s part to be free from the conformity that he felt was strangling Korean society. In Endless Blue Sky, a novel serialized in the Maeil Daily newspaper in 148 installments from 25 January 1940 to 8 July 1941,Lee expresses his frustration with Korean orthodoxy when his protagonist laments that Koreans adopting the traditional white clothing signalled the death of colour in the country.

Lee stated in an essay that he felt no particular emotional attachment to any one place in Korea, that he had no ‘hometown’. Furthermore, several of his protagonists, in what are clearly authorial interventions, state that they feel their spiritual home to be the cultured West. He was personally fascinated with the music, art, dress, and food of the West and, according to one of his students, kept a bar of butter in the desk drawer of his office. He was a coffee lover and stated in an essay that he would gladly travel miles on a rocking bus for a cup of mocha coffee. His literature was also shaped by foreign literary influences from Chekhov, Blake, and Mansfield to Walt Whitman. All of these characteristics helped to form his literary style and themes, and Endless Blue Sky is, undoubtedly, the culmination of all of these influences.

In this novel, Cheon Ilma, in many ways a personification of Lee, travels to Harbin in Manchuria (a surrogate Europe for Lee) where he very literally marries himself to the West in the form of the beautiful Russian woman, Nadia, who speaks English, plays classical music on the piano, and clearly represents the means to fulfil Lee’s longing to transcend the limitations of the time and place of his birth, whether it be the fascism of the imperial colonizer Japan or the stultifying conformity of the Korean Confucian tradition. It is significant that the novel does not end with Ilma leaving Korea to live with his Western bride in a European country but with him bringing Nadia, this symbol of Western beauty and culture, to live with him in Korea. She wears hanbok, studies the language, and loves the food. This can be seen as Lee’s belief that Western culture, if combined with that of Korea, could serve to help the country overcome the difficulties it was experiencing due to colonization and backwardness.

Lee was a cosmopolitan who was overtly antagonistic to expressions of ethnic nationalism. In the story, while in Harbin, Ilma’s friend Byeoksu reacts with disgust at hearing another Korean say how nice it is to meet a ‘compatriot’. Byeoksu responds with the word ‘idiot’ and refuses the proffered handshake. In Endless Blue Sky, Lee also makes clear his belief that love transcends blood. He emphasized that love and mutual understanding can overcome minor differences, such as food and language.

‘… whether one’s hair is black or red, whether one speaks the same language or not, all sit at the banquet of life as equals, and there is nothing remotely unnatural about this. Differences in lifestyle are not fundamental obstacles to harmony. Whether one eats bread or rice is an inconsequential difference. When love is strong enough, the assimilation of the human race is as simple as can be.’

At the same time, Lee was not immune to the effects of assimilation himself. While he was obliquely critical of Japanese imperialism, he had clearly internalized some of its logic. In an essay titled ‘The Shell of the Continent’, he talks about the backwardness of the residents of the colonized Manchuria (which we are supposed to understand represent the Chinese). Lee, while being extremely critical of how Koreans lived in Manchuria (implying most of them were involved in drug dealing and prostitution), makes his views clear when describing virtually the only Manchurian to appear in the text. While marvelling at the ‘grand readjustment’ that was sweeping across Manchuria (colonial modernity), Ilma spies a Manchurian relieving himself in full view of the train:

‘Of course, this grand readjustment was still in its infancy; it would be some time yet before its completion. For example, when the train departed and passed by a long stretch of slums bordering the station, something suddenly brought a smile to Ilma’s face. At the base of an embankment, squarely facing the train, a Manchurian had removed his pants and was leisurely relieving himself. One might call it a humorous scene in the fresh morning air. In any case, it was a far cry from the rather solemn scene at the station. It was difficult to say just how many generations would have to pass before such behaviour also might be readjusted.’

That these somewhat disparate characteristics co-exist within the same novel (and writer) speak somewhat to the complex nature of world in which Lee Hyoseok lived. What can be said about him was that his belief in the healing power of art and love, his universalism, his empathy for the empty husks of the world, and his vision of the possibility of happiness were all sorely needed as the clouds of war were gathering over the Pacific.

In the end, Lee was a dreamer. His alter ego Cheon Ilma uses the word ‘dream’ some seventy-seven times in the novel. Lee dreamt of beauty, art, love and freedom – all obvious themes in Endless Blue Sky. Lee died before seeing whether his dreams would ever be realized. He succumbed to meningitis in 1942 at the age of thirty-six. He was at the height of his literary powers, and one is left to imagine what his contributions to Korean (and world) literature would have been had he enjoyed a longer life and been able to write in a better world.

Steven D. CapenerSeoul Women’s University

ENDLESS BLUE SKY

1. A Bouquet

It seemed as if the late summer sun had stopped moving in the sky, making the heat of the afternoon even more oppressive.

The torpor that lay over the grounds of Seoul Station was in sharp contrast to the ringing clamour inside, indicating the imminent arrival of the 3.30 express train bound for Xinjiang. A single hired sedan made its way to the fore of the countless black automobiles arrayed in front of the station, and from it emerged a man holding a bouquet of flowers. It was the novelist Mun Hun, rather plainly attired. After checking the time on the station tower clock, he entered the building. He smiled somewhat self-consciously at the awkward appearance he knew he was presenting by holding such a large bundle of flowers that was attracting so many stares.

‘Bloody flowers, it’s not as if I’m seeing off a woman or anything …’

While walking through the lobby, Hun ran into the young medical doctor Pak Neungbo, who was also roaming the premises as if in search of something. He was one of the all too many freshly-minted doctors, little black tuft of a moustache and all, that one could see on the streets these days.

‘You bought flowers. Good thinking.’

‘A bit embarrassing, but I figured it was okay between close friends.’

‘What should I get?’

They exited the lobby and paced about in front of the station store.

‘I know. Whiskey. You’ve got to be drunk to venture out on to those Manchurian plains. No one goes to Manchuria sober.’

‘Splendid.’

The two of them – one holding a bottle, the other a bouquet – continued to look for Cheon Ilma, the mutual friend they had come to see off, but he was nowhere to be found.

They went through the lobby once more, looked inside the tearoom, and then ran up to the eatery on the second floor, all without success.

‘I guess spending too much time in Manchuria begins to affect one’s sense of time.’

‘This trip’s different though; I’m sure a lot’s going into his preparations.’

‘If he keeps this up, Ilma may just settle down in Manchuria.’

Ilma had a reason for being late. The regular coach ticket to Harbin he had purchased a few days ago had unexpectedly been upgraded to a deluxe first-class ticket today. Thanks to the patronage of the president of the Hyundai Daily newspaper, with whom coincidence had recently brought him into dealings, the present trip was dubbed a commission. Such work carried with it preferable treatment with regard to travel expenses, as well as considerations relating to the company’s image, and, as such, the order was put in for a deluxe first-class ticket.

By the time he had gone down to the agency, turned in his original ticket, and gotten the new one, the train was getting ready to depart.

There were only thirty minutes left before departure when Ilma and Kim Jongse, a fellow newspaperman who the president had ordered to see him off, finally got in the car for the station. A certain satisfaction welled up in Ilma as he ordered the driver to step on it while sinking back into the plush seat.

‘It’s my first time in deluxe first-class. With a press pass you probably ride in the deluxe cars all the time, but it’s a first for me.’

‘You happy? Don’t waste this chance to turn your life around.’

‘Having my regular coach-class life bumped up to deluxe-class status is almost too much to take in.’

‘I wish you’d quit constantly crying about how poor you are. If they put you in the ultra-deluxe first-class you’d probably faint. You’ve been given the job of a distinguished cultural envoy by the paper – why are you so worried about something so small as a rail ticket?’

‘Cultural envoy – at least the title sounds nice.’

‘Just get up there and successfully close this deal. If things go well, the company, for its part, will certainly reward you, and you’ll be on your way up in the world.’

‘For some reason, I have the feeling things are going to go well.’

Ilma’s duties as a cultural envoy were actually quite simple. He was to go to Harbin and negotiate the invitation of a symphony orchestra. Although there was no mention of an occupation on Ilma’s business card, while writing commentaries on current cultural topics and critical essays on music, he had naturally come to be considered, by himself and others, as a culture mediator. Recent displays of his talents in the field, including successfully arranging for the performances of renowned theatrical and dance troupes from Tokyo, had brought Ilma to the attention of certain people. One of them was the president of the Hyundai Daily, who now had his sights set on the Harbin Symphony Orchestra and had hired Ilma as his representative in the negotiations for a performance. It was something Ilma could have arranged on his own, but, knowing the newspaper’s backing would prove advantageous, he immediately accepted the president’s terms and began preparing for the trip.

‘Anyway, now that I’m a cultural broker, I can rub shoulders with you newspapermen.’

The truth be told, today Ilma felt a sort of pride regarding the work he was now doing for society.

‘In any case, there is no one who would consider you a mere cultural broker.’

Jongse’s reply was, of course, not meant derisively.

‘There may be some who privately don’t like the fact that I received a liberal arts degree and yet am engaged in this sort of work, but I’m not the least bit ashamed. In fact, I’m quite proud of it. I guess everyone’s different, but even when I hear that most of my classmates have risen to become department directors and doctors, I still feel that what I’m doing is right for me.’

‘It would be impossible to enjoy your work without that pride. Honestly speaking, I found the performance you arranged by that theatrical troupe from Tokyo a lot more culturally significant for the common people than all the doctoral dissertations being published these days.’

‘I’m not exactly sure why, but I feel really proud to be going on this particular trip. I’ve been all over Manchuria. I’m so familiar with it that it feels like an outing in my neighbourhood, but I’ve never felt both so anxious and happy about going.’

‘You’re already thirty-five, right? You’ve lived more than half your life; isn’t it about time you started to really make something of yourself?’

‘When I think of my age, I do feel a bit embarrassed, but I’m pretty sure there will be some good things ahead. I can’t keep going on like this …’

As the car stopped in front of the station, so did their conversation.

When Ilma got out he was holding a trunk. The thought of the long trip before him suddenly caused his baggage to feel like it weighed a ton. On this day, he entered the deluxe first-class waiting room imposingly – shoulders, back, and chest out. Compared to the times he had slunk in with an economy ticket, the atmosphere could not have been more agreeable. Hun and Neungbo, who had been running around with their flowers and whiskey, ran up to him and blocked his way.

‘How do you feel about going to Manchuria?’

‘Why are you two making such a fuss? Is it right that I should see two such close friends together at the station when I haven’t heard from either of them in months?’

Ilma, who had spent such a long time in solitude, was in fact gladdened by this small expression of friendship.

‘Isn’t this trip particularly important? I’m your friend, but I’m also a citizen. I can hardly wait for you to return with good news and plenty of quality performances, as well.’

‘What do you think of my present?’

As he took the bouquet Hun thrust toward him, Ilma, despite his indifferent countenance, was rather thrilled. A bunch of flowers so pure could mean nothing but sincere concern for his happiness. He was touched by the humanity of the gesture.

‘Must novelists always give such novelistic presents?’

‘It might have looked better coming from a woman’s hand. At any rate, there’s something awkward about a man holding a bouquet.’

‘Do you know how many years it’s been since I’ve thought of a woman?’

‘I’m no novelist, so here’s a doctor’s present.’

As Ilma finished tucking the bottle of whiskey from Neungbo into his trunk, the following message rang over the loudspeaker:

‘The train for Xinjiang is now boarding!’

Standing up to join the crowd heading for the gate, he could not help comparing the serenity there to the utter congestion of the economy class waiting room. Though Ilma had certainly never longed for class advancement or the complacency that comes with extravagance, this simple realization of the differences between the two waiting rooms made a deep impression on him.

‘You look about ten times better today.’ Jongse, in either complete awareness or complete ignorance of Ilma’s feelings, laughed heartily.

When Ilma, having grabbed a window seat in the deluxe first-class car, came back out on the platform, he looked upon the three friends before him with a feeling of promise and satisfaction. The robust figures cut by Neungbo, Jongse, and Hun – or, put another way, a medical doctor, a newspaper reporter, and a novelist – stood in bold relief against the crowd. When he considered the importance to society of each of their stations, he found them even more impressive and was suddenly overcome with a sense of pride at being their friend. And immediately following his happiness at having such companions, the realization arose in him that he must somehow distinguish himself in order to feel equal to them.

‘You’ll pay for that nose someday.’

Jongse had said this in jest, but Ilma took it to heart. There was Chunhyang’s nose and Lee Doryeong’s from the classic Joseon-era love ballad. It was not insignificant that to these he had decided to add his own and measure himself against his friends for one more push forward.

‘Three people, and one person, and …’

The three people seeing him off and him, the one person leaving. Though he was leaving to bridge (to the degree it was possible) the gap separating them, he also felt it appropriate that he do his all not to fall short of their expectations and solicitations.

Are all these merely the useless musings leading up to a journey?

This was the state of Ilma’s mind today: much too nervous to erase such thoughts.

‘The one regrettable thing, as I mentioned earlier, is that we have no women with us. This is a meaningful send-off. It certainly wouldn’t do any harm to have a bit of colour.’

Hun, as if trying to follow up on what he had said in the waiting room, brought the topic of conversation back to women. It appeared as if he were disappointed that, among the colourful groups of women about the platform, theirs was the only group that stood alone, isolated like a band of Puritans.

‘At this point, what use do I have for women?’

‘That stubbornness will get you nowhere. No matter what the occasion, women always brighten up a scene.’

‘Spoken like a true novelist.’

Neungbo took it upon himself to answer. ‘Ilma said he’s going to find the best woman in the world and have the finest love affair with her. Until then he’s going to cover his eyes and ears; he’s determined not to play around. It will take a very special woman to get his attention. A merely average woman showing up for this send-off would have done nothing for him.’

‘Do you think it’s right to be so stubborn just because you failed in your first attempt at love? I don’t know how you can live so rigidly.’

‘Don’t you worry. Someday I’ll have a woman who’ll surprise you. You can say whatever you want till then.’

‘A world-class love, do you mean like the Duke of Windsor?’

‘Who knows what will happen?’

‘As long as you’re going on this trip, you might as well bring back love along with art.’

‘I hope all goes according to my wishes, but who knows what the future holds?’

While all of them were laughing heartily, an announcement for departure came over the loudspeaker, followed by the ring of a bell.

‘It’s only a brief parting. I may look different upon my return.’

‘We’ll be counting the days till you get back.’

Ilma got back on the train and looked out on his friends through the window. Now, as he was departing, he felt the distance between them widen and the feeling that he was the one leaving deepen.

Be brave. A real man can redraw the map of the world. One, two, three!

As soon as the train began moving, Ilma steeled his nerves and waved out of the window. The figures of his three friends waving their hats faded into the distance.

The blue silk seats were immaculate, and their backrests were draped in white cotton, but these were not the only things different about this car; the appearance and bearing of its passengers also set it apart from standard class. Whether soldiers, government officials, businessmen or ladies, their attractive and smart appearances silently boasted of their places at the top of society.

Ilma could not help but wonder where he ranked among them. And though he had purchased his place among them merely by adding a bit of money to his standard-class fare, he could not help but feel it was all sort of magical. He had made this trip so many times, only a month ago in fact, and on the very same train, but that day was his first with a business ticket.

Having no vase, he put Hun’s bouquet, still wrapped in waxed paper, on the windowsill. When he looked about the car, the pleasant movement of the train brought with it a stream of thoughts about his voyage. With those flowers and in that car, he felt he was happy; he certainly wasn’t unhappy.

He thought of the title ‘On a Journey with a Bouquet of Flowers’. Even though he had taken the path of the wanderer frequently over the past few years in search of he knew not what, never had a trip felt this right; this time felt like nothing less than the road to happiness.

Happiness – for the first half of his life, just how well had the goddess of fortune looked after him? The sixteen years he’d spent in school had been by no means favourable. Rather, they were a time of uncertainty and anguish. Even once he had finished school, it was not a path to easy advancement and success that awaited him. Following his own path in search of work to his liking had brought him to try his hand at today’s unconventional and somewhat absurd business. But it was a wholly original and arduous path with neither predecessor nor guide. Far from smooth, the first half of his life had been crooked and thorny. Even failing at his first love paled in comparison to the tragedy he had suffered just a few months ago – the loss of his mother, the last living member of his immediate family, had dealt his spirit a crushing blow. He felt it was his final misfortune.

He’d gone to her as soon as he received the telegram, but she was already in critical condition. Being alone, she’d gone to live with a close relative, and it was there that she’d fallen ill. The fact that Ilma had put off living with his mother until his own life became more stable, at which time he had planned to bring her to Seoul to finish her life in peace, made his grief all the greater. He was beside himself and merely cried inconsolably at her sickbed for several days. His crying turned to wailing when, in her final hours, he realized the depth and consistency of his aged mother’s love. In her will she had left him a small plot of land; though too insignificant to be called a fortune, she had held onto it for all those years. Trifling as it was, it pained Ilma to his bones. But as death is a natural part of life, he simply had to deal with his feelings and wipe away his tears. Putting the past behind him, Ilma summoned all his courage. He sold off his inheritance, said farewell to his relatives, and returned to Seoul as if being chased by something. He was now truly alone, with no one to care for and no one to care for him. But even amidst suffering and death, life goes on. He gritted his teeth and was swept back out into life.

That’s all in the past. I hope this is the end of my misfortunes as well.

In fact, Ilma began to feel a keen premonition that this would spell the end of his ill fate. When he stepped out into the streets with the money from his inheritance, the desire to embark on some new enterprise welled up within him. This was partially what brought him to agree to his present duties as a cultural envoy with an unprecedented combination of anxiousness and expectation.

In the deluxe first-class car today, his expectations once again soared, and he thought this trip, begun holding a bouquet, was headed straight for happiness.

A new heart, a new beginning …

This thought kept coming to him, making the scenes passing his windows all the more to his liking.

*

It was seven in the morning when he awoke after a night in the sleeper car. The train was stopped at Bongcheon station.

We’re all the way into Manchuria now.

Rubbing his eyes, Ilma looked out the window onto the dim platform. He had passed this way many times before, so nothing struck him as particularly curious, which is why he had slept so soundly. But when he saw the gang of coolies working lazily in the station yard and the attitudes of the station attendants supervising them, he could not help but feel the change in the times and the movement of history. Something about it was imposing and serious so that it gave a distinctly different impression from that of six or seven years ago. This was because the old had been replaced by the new, and a grand readjustment had begun. Ilma could not look upon the tremendous changes over the past several years without a combination of wonder and lamentation. He experienced these emotions whenever he travelled this road.

Of course, this grand readjustment was still in its infancy; it would be some time yet before its completion. For example, when the train departed and passed by a long stretch of slums bordering the station, something suddenly brought a smile to Ilma’s face. At the base of an embankment, squarely facing the train, a Manchurian had removed his pants and was leisurely relieving himself. One might call it a humorous scene in the fresh morning air. In any case, it was a far cry from the rather solemn scene at the station. It was difficult to say just how many generations would have to pass before such behaviour also might be readjusted.

Unable to rid himself of the smile from the morning’s scene, Ilma washed, tidied up a bit, and then had breakfast in the dining car, after which he returned to his white-backed seat. His mind clear, today felt like yet another enjoyable day on his journey. He looked out upon the broad Manchurian plains. The boundless plains had neither mountains nor streams but were covered in green vegetation and abundant grain. Here and there, clusters of sunflowers ripened yellow, strong and splendid as if having drunk in the very essence of the sun. If any man looked after these plains he was now hiding, for not even his shadow was visible upon the great expanse. Ilma could not contain his sense of wonder at the thought that on these fertile plains, though infinite time had passed, history was now, unbeknownst to any man, being rewritten.

It is not the innocent plains that change but the men who rule them, the masters. Truly, only men can change.

Other thoughts followed this one like a runaway horse and galloped along the plains.

The train had passed Chollyong, and Sipyongga was almost in sight. It appeared that a railroad police officer had begun making his rounds. Ilma immediately recognized him, though he was dressed in plain clothes, as he began checking seats from the far end of the car. Once he had received a business card, the officer usually moved on without saying much. He remained a bit longer in front of Ilma’s seat, however, because there was no mention of an occupation on his name card.

‘Where are you going?’

‘To Harbin.’

He had gone through the same routine twice already, once with a police officer and once with a customs agent when crossing the border the night before. And he had also been through it innumerable times on his previous trips, all of which allowed him to maintain an attitude of composure.

‘What for?’

‘I’m on my way to Harbin to invite a symphony orchestra, but I’m not sure what to call my job. Though it’s a type of cultural work …’

As he made his way through this awkward explanation, the thought occurred to him that he should have had some business cards printed for this work with the newspaper, even if it was only temporary. In order to produce the card he had received from the president of Hyundai Daily to show that he was, in fact, affiliated with a newspaper, he reached into his pocket and pulled out his organizer.

‘How much money are you carrying?’

‘I only brought a few hundred won.’

He pulled out his notebook as he gave his reply. The many cards he had placed between its pages fell and scattered, but a single piece of paper, folded many times over, stood out among them.

There was no need to pick it up and unfold it, for it was a lottery ticket, nothing special to Ilma, the officer, or anyone, for that matter, who had spent considerable time in Manchuria. It was a single National Prosperity Lottery ticket, issued by the government of Manchuria.

‘What’s with the lottery ticket?’

Ilma smiled as he replied to this question from the plain-clothes officer, ‘I bought it on one of my many trips to Manchuria.’

‘But only residents of Manchuria are allowed to purchase these.’

‘Well, I’m not a resident, but I may as well be. I am here so often that I buy a few each year.’

‘Have you ever won?’

‘Ha, I wish. No, I lose every time.’

It appeared a single lottery ticket had been enough to put the policeman’s mind at ease.

‘Why don’t you pick some numbers for the 10,000wonprize?’

‘Having your numbers drawn from among the hundreds of thousands out there doesn’t happen to just anyone. It’s the kind of luck you might happen to see once in a lifetime. You make it sound so easy.’

‘There’s not a single Manchurian who doesn’t buy one each month. Some even say they live in Manchuria for the pleasure of buying lottery tickets. In fact, I have one too.’

‘We’re just the same, you and I.’

‘If I had 10,000 won, you think I’d be a goddamned cop?’

Considering the policeman’s own confession, it seemed that all those living on the plains were exceedingly familiar with the dream of the lottery. All men carried the desire for good fortune in their hearts; it could hardly be considered a crime.

Truth be told, no Manchurian could resist the temptation of the lottery. The government, using the great fortune associated with winning as bait, divided its financial burden among hundreds of thousands of citizens. With the money thus gathered, it awarded a few tens of thousands ofwonto winners, while using the remaining several hundreds of thousands ofwonfor national relief projects. But, much more than from a clear conception of such important relief works, the average citizen’s impression of the lottery came from the allure of, and excitement at, the possibility of winning. They had no need to consider the precise relief project from which the benefits of this huge sum, to which they had each contributed, would trickle down to them. Rather, people in the city bought tickets there, while farmers in the countryside quietly asked those venturing to the city to buy them tickets with a fewwonof their hard-earned money, and travellers like Ilma bought a couple for amusement on their journeys and kept them crumpled in their pockets. It was enough for all of them to await the announcement on the fifteenth of the following month and, discovering whether they had won or lost, to laugh or cry accordingly. Whether they tasted the great fortune of winning or the pain of losing, what was truly important were the dreams and worries brought by the thirty days of excitement and stimulation leading up to the fifteenth of the coming month. The rich dreamt the leisurely dreams of the rich, while the poor felt the desperate desire of the poor, but the inspiration and stimulation of the experience was the same for all. When they were fortunate enough to win, they could dance with joy, and when they lost they could just choke back their tears, quietly buy another ticket, and keep it with redoubled excitement while awaiting the results of the coming month. They might spend an entire lifetime being deceived, but, if they could live in constant anticipation, was it not a bargain?

‘It’s a sort of national gambling.’

Ilma had no reason to be overly critical of this national event for he, like a Manchurian, purchased that month’s happiness for a fewwoneach time he passed by Shingyeong.

Now that he thought of it, even the officer who had come to question him admitted to participating in this gambling. It appeared that all people took pleasure in the same sorts of things.

The officer had begun quite sternly, but, thanks to the ticket, his face had softened, and, without asking any further questions, he disappeared toward the rear of the car with a smile. Ilma was so pleased that he even purposefully unfolded his ticket for another look. It was composed of five sheets, each of which had the following numbers clearly printed on it: 3 7 5 2 5. He smiled again and mumbled to himself.

‘3 7 5 2 5, thirty-seven thousand five hundred and twenty-five – is this a lucky number, or an unlucky one?’

*

Having passed Sipyongga and arrived at Gongjuryeong – or Princess Pass – Shingyeong was now no more than an hour away. The feeling of excitement at the unexpected good fortune brought by the lottery ticket still fresh, Ilma basked in a proud feeling of pleasure at the trip.

Gongjuryeong – the name was beautiful no matter how many times he heard it. In front of its rustic station lay flower beds with crimson salvias in full bloom and a sparse elm grove, beyond which he remembered its quaint streets. As he imagined the residential area, with its roads lined with old Russian-era buildings, on the far side of this small city, it brought him pleasure to consider just what sorts of lives were being lived there.

Was it named Princess Pass after the legend of a princess?

Lost in such thoughts, Ilma was still looking out his window in wonder when the train began to move.

‘What are you staring at?’

Someone had suddenly appeared at Ilma’s side and covered his eyes with her hands, depriving him of Gongjuryeong’s scenery.

Even though she did not give off the warm air and fragrance of spring, her soft hands and voice were enough to tell him she was a woman, but, beyond that, Ilma was powerless to guess who she was. That said, he also felt no need to push her hands away and so, softly questioned her.

‘Who are you?’

‘Why don’t you guess?’ the woman replied in a clearer, higher voice, after which she affected a laugh.

‘Are you a nymph fallen from the heavens?’

‘Why not say I’m a princess come down off the pass?’

‘But I don’t know a single person in Manchuria.’

He did not know any women in Manchuria, and it would have been impossible to get to know one on such a short train ride.

‘I followed you all the way from Seoul. I’m sure you never dreamt that I slipped onto the same car as you yesterday afternoon. Although now you should know who I am.’

She removed her hands, but, of course, Ilma was able to speak her name before turning to face her.

‘Is it you, Danyeong?’

Upon actually seeing her, his eyes opened wide in surprise.

‘What are you doing here?’

‘I was certain when I boarded the train, but I worried the whole night through about whether what I was doing was right or wrong. I didn’t sleep a wink.’

As she plopped down listlessly in her seat, Danyeong’s face, which should have been happy, was filled with gloom.

‘Just where do you think you are going, following me like this? I think you’re lying.’

Ilma stared straight at Danyeong, who was dressed rather extravagantly, his shock not abated in the least. With her hair permed and cut in a bob, her make-up heavy, and her impeccable Western-style outfit, she brought a singular splash of colour to the otherwise dreary car. People took notice, though no one needed to say a thing; her appearance made it obvious she was an actress. Perhaps due to her having agonized through the night, to Ilma, who saw her quite regularly, she appeared a bit haggard.

‘I have no idea what I’m doing. Even though I’m afraid of what might happen, I just can’t seem to control myself. I knew you were travelling deluxe first-class, of course, and even saw you from a distance at the station with Hun and the others but actually coming to see you proved to be difficult. I tossed and turned all night, then, as we got close to Shingyeong, I forgot my pride and just came running to you. You must be surprised, but please forgive me. Now that I see you, I feel ashamed again, but last night I could think of nothing else.’

‘Following me here is no good. As I’ve told you so many times before, my mind is set. I couldn’t change it even if I wanted to. What use do I have for women? I am determined to stay absolutely focused until I achieve my goals.’ There was an unmistakable tone of reproach in Ilma’s voice.

It seemed proper to call Danyeong an actress. After all, she was under exclusive contract with Bando Studios and appeared on the silver screen in a couple of new films each year. Most knew her as a femme fatale, and she was quite famous in the struggling movie industry. On screen she received applause, while on the street she was recognized by fans, often becoming the topic of conversation. But Ilma paid much more attention to her sordid private life than to her social position as an actress and, as a result, was left with the impression that she was unwholesome. When he became aware of her chaotic personal life and frequent liaisons, he began to consider her not as someone beneficial to society, but rather as a noxious insect poisoning it. Of course, he knew that this unsound society was capable of producing at least one such pathological individual, but the more he thought about it, the greater his disgust grew, albeit not without a touch of pity.

Although he had long been aware of Danyeong’s adoration for him, Ilma had remained aloof. For one, beyond his criticisms of her character, she simply was not his type. And, secondly, he really had no use for women at the time. Having rebuffed her on numerous occasions in Seoul, he’d had no idea she would follow him, let alone appear so far along on the journey. Ilma could not help but be taken aback.

‘When we are apart, I become brave. When we meet, my courage fades, only to return when we are apart again. At this rate, I may follow you my entire life.’

Such sultry displays of passion only made Ilma more uncomfortable.

‘Think of Hun. Aren’t you ashamed?’

The novelist longed for her, but Danyeong hardly acknowledged his existence.

‘I can’t help it if I don’t like him. For some reason I could never love Hun. Though I do appreciate that he’s interested in me.’

‘I feel the same way about you. Hun is my friend. Just thinking of what it would do to him is more than enough reason why I could never be with you. Look, he’s the one who gave me this bouquet.’

Danyeong just hung her head, not saying a word.

In the midst of the silence, the train pulled into its final destination of Shingyeong. Ilma felt relieved at the release this provided from the awkwardness of sitting there with Danyeong.

‘What are you planning to do? I’m going to take the afternoon train to Harbin, so why don’t we say goodbye here?’

Danyeong went back to the third-class car, retrieved her things and walked with Ilma out of the station. The sight of her walking along like a kicked dog bothered Ilma.

‘We will say goodbye, but why don’t you stay in Shingyeong for one night? You still have a long way to go.’

‘I’m too busy to dawdle. I’ll stop by on my way back.’ Closing his ears to Danyeong’s suggestive offer, he steeled himself against the temptation.

‘Then can we at least go somewhere and have a meal together?’

‘Let’s eat here.’

By the time he had wrangled her into the crowded station restaurant and found a seat, Danyeong was crying. She wiped her eyes with a handkerchief and then blew her nose into it. Even this seemed seductive and so Ilma said, in as cold a voice as he could muster, ‘If you don’t have any special plans, why don’t you go back to Seoul on the next train? I don’t think it’s a good idea for you to be all the way out here by yourself.’

This was too much for Danyeong and her face blazed red in anger.

‘Are you trying to insult me? And why do you care anyway? Isn’t that a completely different problem?’

‘It’s just that I’m worried about you, and …’

‘Just please stop … I get it. After you’ve been hurt by your first love you can’t let another woman in. Miryeo? Is Miryeo the only woman in the world? Is she better than all other women? If you happen to see her, please let her know how I feel.’

By bringing up the name Miryeo, Danyeong was intentionally rubbing salt in a deep wound, and this instantly set Ilma off.

‘How dare you!’ he shouted, but Danyeong didn’t even flinch.

‘I know all about it,’ she said with a great show of irritation.

Deciding that further argument would be pointless, Ilma clenched his teeth and began to write a telegram on the restaurant table.

Arriving Harbin at 6 p.m.

The telegram was going to his good friend Han Byeoksu, a reporter for the Harbin Daily newspaper. He would separate from Danyeong here and leave by himself for Harbin on the one o’clock train.

2. A Certain Family

The editorial offices of the Hyundai Daily newspaper.

*

True to its status as a major newspaper in a capital city, the external appearance of the building was impressive, and the scale of the spacious, bustling interior of the editorial offices was no less imposing. It was late in the morning, and dozens of employees were toiling at their assigned desks to prepare the evening edition of the paper. Pens were racing across manuscripts, desktop phones rang incessantly, and there was a continuous drone of voices.

A young woman came out of the president’s office, wound her way through the maze of desks and stopped in front of the entertainment desk where Kim Jongse was absorbed in his manuscript. At one time, Jongse had made a name for himself at the social affairs desk, but he had since moved to the entertainment desk.

A man that possessed both of these talents was very useful to the newspaper. It was the day after Ilma had been sent off to Manchuria; Jongse’s excitement had cooled, and he was now able to concentrate.

‘The president would like to see you.’

In response to the office girl’s words, he looked up and, brushing a wisp of hair out of his eyes, said, ‘I’m quite busy, what’s this about?’

‘He says it’ll just take a minute.’

Throwing down his pen, Jongse followed her to the president’s office. His first thought was one of annoyance.

The president, who had been talking with the editor-in-chief, quickly offered Jongse a seat.

‘Sorry to bother you when you’re busy. Sit down for a moment.’

Whether the reason for this summons was something irritating or pleasant, when Jongse was busy he didn’t like to be disturbed.

‘Give the article you’re working on to someone else; I need you to go somewhere.’

Seeing the smile on the normally illiberal president’s face put Jongse at ease.

‘It seems like this project is going to be a success.’

Jongse immediately intuited what this was about. ‘Are you talking about the plan to invite the symphony orchestra?’ he asked, guessing what was coming.

‘Not only was this the right time for this plan but your recommendation to send Ilma was good work as well.’

‘Well, there’s no doubt Ilma will do a good job.’

‘We’ll have to wait to see how it all turns out, but the praise and positive responses have been rolling in. By phone and letter.’ The editor-in-chief appeared pleased as he looked through the postcards and letters on the desk, ‘We just got a phone call from someone who is in discussions with the editor to unconditionally sponsor the event, but we wanted to hear what you think since you’re involved in this project.’

‘If they want to sponsor it we should accept. The project will thrive, and we’ll get good PR from it.’

As if Jongse’s amiable response was just the answer he wanted, the editor-in-chief said, ‘We agree on this, then. In fact, this is not a small undertaking for the paper, and the early positive responses are very reassuring.’

The president added, ‘You know who it is. His name’s Yu Manhae of the East Asia Trading Company. He just called from his home offering to sponsor us and said if we send someone over he’s ready to come to an agreement.’

‘Yu Manhae? Even though he’s a businessman, he’s quite familiar with cultural entrepreneurship. His proposal is a decent one.’

‘Yu Manhae is a clever person who intends to make a profit in this project, that’s why he accepted the offer.’

‘Foreign trade may not be doing well, but I’m sure he has made several hundred thousandwonin metal goods and gold mining. He’s said that he’ll invest a thousand, or even ten thousand in a cultural enterprise, but that won’t even put a dent in his pocket. There’s no reason to turn down such a rare offer.’

‘I want you to go and meet him.’

‘Of course, I’ll go. Since I’m already involved in this project, I’ll wrap this up no problem.’

Jongse’s answer pleased both the president and the editor-in-chief.

*

Yu Manhae. I suddenly get to go see Yu Manhae. This should be good.

Muttering to himself after returning to his seat, Jongse hastily wrapped up the article he had been writing, handed it over for editing to a colleague sitting next to him, and left the office.

Even if this is fate, it’s somewhat incredible. It seems I run into him every time I turn around.

In addition to the excitement of being assigned to go see the young businessman Yu Manhae, the unexpected events of the morning held another hidden significance for Jongse. Yu Manhae was of interest to Jongse not only because he was a well-known businessman but, truth be told, also because he shared a strange bond with Jongse’s friend Ilma. When seeing Ilma off at Seoul Station, Ilma had been going on about the failure of his first love; and the name Miryeo, which Danyeong had vexed him with in the Shingyeong station restaurant, was not only the name of that first love but was also the current wife of Manhae. For people who knew about this strange connection between Ilma and Manhae, it was a topic of clandestine conversation, and the memory of that time was still enough to upset Ilma. Of course, as Ilma’s friend, the situation was of great interest to Jongse. The concern of Ilma’s friends over this situation was widely talked about, and, of course, the way things had turned out between Ilma, Manhae, and Miryeo had been affecting Ilma ever since.

Ilma and Manhae were a year apart in school and Miryeo had been the object of both of their desires. In the mundane world, they say the best weapon with which to win in love is wealth. Victory between Ilma and Manhae was decided by this commonplace criterion. Ilma’s defeat was attributable to the fact that he was a lowly scholar who had graduated from a college of liberal arts, while Manhae’s victory was due to the fact that he was a law graduate who had inherited a large fortune. Only time would tell whether Miryeo had made the right choice or not, but while things had turned out the way Manhae had wanted and he was happy, Ilma’s disappointment had been immense. Ilma was invited to the wedding, where he hid himself in the crowd and cried softly like a movie actor. Seven or eight years had passed since that dramatic scene. While Ilma had, up until this very day, been making his way along a rocky path, Manhae had been utilizing his substantial capital to get into the trading business, which had flourished to the point that he could enter the steel and gold mining industries, thereby increasing his fortune and making a name for himself as a young entrepreneur. The obvious distinction between the two of them was a continuing source of public attention and had captured Jongse’s interest as well. It was as if there were two lives being played out in the same city, one happy and one sad, and the vicissitudes of these two lives were secretly a topic of interest to their friends. This was the cause of the excitement that Jongse felt upon being given this unexpected responsibility.

This is no ordinary stroke of fate.

This was just too delicious to keep to himself, and so Jongse looked for Hun in their favourite teahouse, but it had not opened yet. Feeling vexed at not being able to sit and indulge in some juicy gossip with anyone, Jongse, partly to look more dignified, changed his mind about taking the trolley to Seodaemun and caught a taxi instead.

‘To Yeonhuijang, and step on it.’

Feeling the same sense of adventure as when going out to cover an accident while working in the social affairs division, he sat back in the seat.

The comfortable, shiny car ran along the trolley line, went up the street to Geumhwajang and then entered the street to Yeonhuijang. Pointing out the fancy red roof of the Western-style house that stood out even in this neighbourhood, Jongse once again gave Yu Manhae’s name to the driver.

*

In the parlour of Manhae’s red-roofed Western-style house earlier that morning, there was a discussion under way between him and his wife. After finishing a late breakfast and retiring to the parlour to leaf through the morning edition of the paper, Miryeo brought her husband’s attention to one of its pages.

It was the Hyundai Daily. He took in the article with one glance.

‘That’s quite a project,’ Manhae exclaimed. It was an article about the symphony orchestra invitation. The project was reported in block letters in a five-column article.

‘Joseon’s1 music society is quite something if they can bring in a foreign symphony orchestra.’

Miryeo could not suppress her delight at the news.

‘How many people do they think can appreciate such music?’ asked Manhae.

‘What are you talking about? Don’t you know that in the last few years the average person’s level of musical sophistication has vastly improved?’

‘How much could it have improved? Do they really know anything about it? They’re just acting as if they do.’

‘If you’re not careful, you’ll be the only one who doesn’t know anything about it. Soon you’ll be the only one who could be called modern that doesn’t know who Beethoven or Chopin is. Do you actually think there are people who wouldn’t like to hear such music?’

When it came to things like music or art, the couple never agreed. Miryeo was a thoroughly modern woman who, having received a specialized college education, was extremely cultured with an especially good knowledge of art and culture. On the other hand, Manhae, in spite of the excellent education he had received, had a lower than average, superficial understanding of such things and was unyieldingly conservative in his views.

‘The project is proceeding after taking account of the general populace’s level of cultivation. Would they attempt such a large project recklessly? It’s an extremely valuable undertaking. We aren’t the only ones who’re happy to see this kind of project get off the ground.’

However, Manhae, not fully comprehending, had a different opinion. ‘Simply put, it’s nothing but vanity. The project is vain and to approve of it is vain. They are trying to drive simple citizens into the same pit of vanity.’

‘What do you mean, vanity? Why is it vain? Is it fair to label as vanity the citizen’s attempts to understand art?’

For some reason on this particular morning, Miryeo just couldn’t abide her husband’s opinions and ended up losing her temper. As her tanned face took on a look of aggravation, she stared into her husband’s equally tanned face. It had only been a couple of days since they had returned from a two-week vacation at the beach.

As they went to the same place every year, their vacations did not provide any novel sense of happiness to the couple. That said, the trips were not unpleasant either. After returning from the annual event that played out as if scripted, the couple was lazily spending a few torpid days at home experiencing a completely new sense of fatigue. As it was the height of summer, there was no particularly pressing business, and Manhae had not gone to his office but was resting up at home. As far as a family goes, it was just the two of them and the hired help; the small household meant that Miryeo spent every day with her husband, which she found tiresome. When people feel stifled, they are apt to give vent to their feelings for no apparent reason. On this particular morning, that unexpected newspaper article was the thing that ignited the explosion.

Miryeo’s face turned red and blood rushed to her temples. Compared to her husband, whose straight nose and shining eyes gave off a softness that concealed a lively nature and, therefore, gave off no particular impression other than amiability, Miryeo’s face possessed a strong tenacity. She had been the talk of the town before she was even thirty, and her exceptional countenance was without a blemish, like a genial flower. Was it that a beauty who can control her aggravation seems even more attractive? The knitted brow on her tanned face made her seem exceptionally beautiful on this morning.

‘Vanity, you say. You are only insulting yourself with such talk by displaying how little you know.’

‘If it’s not vanity, then what is it? One’s belly has to be full before worrying about culture. If pursuing music or art without being able to feed yourself is not vanity, tell me what is.’

Manhae too was not going to give in easily, and an unexpected confrontation developed between the couple.

‘It seems you think that food is the only thing people need to feel satisfied. Music is a kind of nutrition as well. You talk only about the stomach but forget the soul.’

‘So music alone can fill an empty stomach. Why don’t you try living on nothing but music then?’

‘Ha! You go on like that, all the while pretending that you’re engaged in some big enterprise when you’re just a merchant. You use the word “businessman” and think the world is yours, but do you know that behind your back people call you a miser? Why is it that cultural projects can only happen after one is living well? Can’t you see that even the poor desire such things?’