Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

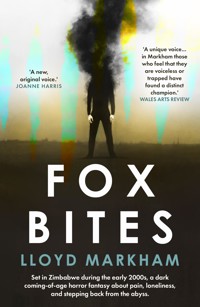

'a new original voice' – Joanne Harris 'A unique voice... in Markham those who feel that they are voiceless or trapped have found a distinct champion.' – Wales Arts Review When Taban wishes for the world to end something out there . . . hears him. Soon the young boy is being stalked by a fox whose salivating jaws drag him into strange dreams. Dreams where he is a revolutionary with ancient psychic powers fighting against a tyrannical regime. He awakes with glowing scars that only he can see and the lingering embers of telekinetic abilities. Honing this flicker of power over years he plots revenge on the bullies who've abused him. In exchange he will become the conduit for the world's end. But what if he changes his mind? Surely we can all come back from the edge? Can we? Set in Zimbabwe during the early 2000s, amidst a backdrop of political turmoil, Fox Bites is a dark coming-of-age horror fantasy about pain, loneliness, and stepping back from the abyss.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 361

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Content WarningOn a couple of occasions characters use ableist and homophobic language. There is also one instance of racist language. This is unfortunately accurate to the time and setting of the story. We provide this information in advance in good faith so readers can be prepared.

iii

FOX BITES

Lloyd Markham

Acknowledgements

Funded with help from The Literature Wales Writers Bursary

With Special Thanks to Crystal Jeans and Chris Winters for their feedback on various drafts and redrafts of this story

Desmond Barry, Rob Middlehurst, Philip Gross, and Chris Meredith for their guidance during the early days of this book’s inception

Alex Haagaard for providing a fount of interesting medical knowledge and great suggestions

Emily Rose Harrison for her wonderful illustrations and support

And Susie and Rich for their patience and encouragement

v

Dedicated to the people of Zimbabwe, my family, and childhood friends

Particularly those no longer with us

I have never stopped missing you

vi

The following is a work of fiction

It is inspired by events from the author’s life, but it is not an account of it

Nor are any of the characters veiled depictions of people the author has known

It’s a bad dream, friend

Step into it with love and know there is light on the other side x

xi

Our greatest mistake was believing that knowing was the same as understanding.

– Brother Antal of The Bronze Cast, extract from The Final History Of The Triumvirate of Metals.

Contents

Black Diamond Fox BiteorA Giant Rests Beneath A Hateful Sun2

Caleb is everything Taban is not. Tall. Tanned. Muscular. Possessing wide blue eyes full of expression and light. Wide blue eyes that are weeping.

Pale, short, sickly, Taban has never wept. In his fifteen years alive his face has been an uncrackable mask. Neutral or neutral-smile. A little dash or minus sign. Sometimes with a slight curve, but usually like this → ‘–’

His narrow eyes are near-black brown. They don’t let the light in. They don’t let anything out. Even when Taban wants them to.

Caleb’s mother, Gertrude, stands next to her grieving son, hands shaking, sharply inhaling, containing something violent inside. Her shark-fin quiff has gained new streaks of grey.

‘Sorry we’re late,’ Taban’s mother says. ‘Traffic was a nightmare.’

‘It’s okay.’ Gertrude squeezes Ann’s hand. ‘We’ve still got fifteen minutes. Catch your breath.’

A dusty wind blows. Ann’s auburn mane flickers up like flames and for a moment the stagnant smell of oil from the nearby petrol station is displaced by the heavy stink of cattle shit.

Ann’s nose curls. ‘Yuck.’

‘Probably a farm upwind,’ Gertrude says.

They turn to face the structure behind them. The Harare Fifth Church of Saint Maurice. White and green – the paint could use a touch up. The little cross sticking out from the top of its triangle roof is the only indication it’s a church and not a farmhouse.

Apart from the TOTAL petrol station opposite, The Fifth Church of Saint Maurice is the last building before the city breaks up into rural expanse. Pockmarked tarmac, brick, and concrete give way to sun-bleached grass. Lonely 2-to-4 lane highways melt into the horizon.4

Ann smiles sadly. ‘Don’t know why we’re doing a service at this old place really. My brother was quite godless.’

Gertrude doesn’t register the statement. Her mind has been re-abducted by grief.

Ann’s smile dissolves into a grimace. ‘I guess Mom and Dad would be glad. Weird seeing the old place after all this time.’

Seeing a break in the conversation, Taban attempts to say something to Caleb, who is staring at his shoes, face wet with tears. He wants to say, ‘I’m sorry. I love you.’

Instead his mouth hangs open for a moment, then quickly shuts. He wanders a few metres back to the car, where his father, Cormack, is having a smoke.

Cormack points across the road. ‘Check out the old madala.’

On the sidewalk by the petrol station, a craftsman sat on a grass mat – soapstone sculptures splayed around him – is focused on a prowling tsetse fly. The bug affects disinterest – like a cat slinking nearer and nearer its master’s plate. The man doesn’t buy the act. Bony fingers twitch. Thwap. A rolled-up copy of the Daily News flattens the blue buzzing orb against the head of one his sculptures.

The old man spots Taban and Cormack watching. He waves – smile surfacing from his greying bristle beard.

Cormack waves back. His thick moustache crests – revealing a smile awkward and unequal to the old man’s sincere toothy beam. Looking both ways, he crosses the street.

A short conversation follows sprinkled with Shona and slang: Shamwaz. Mushe. Tatenda.

Cormack returns with a nyaminyami necklace. ‘Heard these little snakes are meant to bring good luck.’ He places the charm around Taban’s neck.

‘Why didn’t you get one for yourself then?’ he asks.5

No answer. Another awkward smile.

Taban stares at the sculpture splatted with diseased insect guts.

It’s of a jackal.

Or maybe a fox.

Even here it is laughing at his pain.

Perhaps it is right to.

A voice, not his own, quiet, internal: You asked for this.

Ann calls to them, ‘We better go in. It’s starting now.’

Taban heads towards the church. Cormack stubs out his half-finished cigarette, pops it into his top pocket, and follows after.

A priest, tired, overworked, greets them by the door and hurries them to their seats at the front where the seven-foot-long casket of the gigantic Uncle Athel dominates the room. He is dressed like his mourners – formally, in a manner he would’ve hated were he still alive. His face, usually earthy and red, is drained – the only face that isn’t sweaty in the freakish off-season heatwave.

Gertrude, Ann, Taban, and Caleb each take a seat. Taban in the middle, Ann is to his left, Caleb to his right, Gertrude at the end of the row, by the aisle – closest to her beloved Athel. Cormack hovers. There is no room for him. Someone rushes over with a chair, apologises for the mix up in the seating arrangement. He sits down – an awkward appendage to the row, obstructing the aisle.

The priest stands at the podium and attempts to transmute the life of the man who lies silent and boxed before the congregation into a story – into a sequence of soothing words. His tone is distant and professional. He is in a rush. He has many more funerals to get through. 6

Caleb raises his hands to his face as if trying to shield his eyes from a searing, painful light. His gentle weeping turns into a howling sob.

Taban tries again to say something, but cannot. Instead he lightly squeezes his cousin’s shoulder. He thinks that this is something he should do. A way of performing his love for Caleb who he admires more than anyone. A way of performing his sorrow for the loss of Athel who was dear to him. A way of suppressing his shame – his guilt.

Taban feels guilty.

He is responsible for this tragedy. Most here believe that Athel’s death was an accident – that he’d accidentally overdosed on his medication after having one too many drinks the evening before. Others whisper that it was an intentional act. That he just couldn’t bear losing the old family farm – after spending so much effort and treasure to repurchase it. But Taban knows the truth. It is all his fault. Athel’s death was the result of a curse that is running out of control – a curse he let into the world.

Taban can feel the presence of the swollen moon above them. Ever since that horrible evening it has hung brazenly in the daylight sky. Though no one else seems to notice. Every morning he wakes to find it larger.

The Black Diamond Fox Bite by his collarbone itches.

It smells of charcoal.

It looks like this → 7

The text describes three ‘casts’. 1

There are the Bronze Cast – who are gardeners. Though ‘gardener’ is a bit euphemistic. ‘Geo-engineers’ would be a more accurate analogy given the abilities described. Their symbol is the Sickle & Tree.

There are the Silver Cast. They are ‘guardians’ and sometimes ‘metallurgists’ – soldiers and scientists. Their symbol is the Snake & Dagger – which in the past has unfortunately led to a lot of spurious and culturally insensitive speculation. In the 1990s some academics from our country noted that the fragment was found in the Zambezi and predated known records of the Tonga people’s Nyami Nyami legends. Based on this and this alone they leapt to theorise that their serpent guardian legends must have originally been ‘inspired’ by this tablet or perhaps ‘passed down’ from the people who made it.

To these theories we simply say: the tablet also predates all Viking myths by thousands of years and features extensive descriptions of a ‘World Tree’ and yet no one has attempted to claim that this must mean that all Norse Mythology must be credited to the makers of this strange broken slab. Some academics reveal more about themselves than their subjects when they use amazing discoveries like the Zambezi fragment as a pretext to explain away the accomplishments of other cultures.9

Finally, there are the Gold Cast – ‘overseers’ and artists. ‘Overseer’ here seems to be a role that combines administration, diplomacy, and regulation. Bureaucrats and painters essentially, with a slight mystic air, and some allusions to supernatural abilities. Their symbol is an eye within an eye.

The fragment insists that all three casts are equal in stature, but placed separately into roles best suited to their skills.

Funnily, it is this and not the heavenly trees or miraculous powers which we find most difficult to believe.

1. There is an interesting ambiguity as to whether the author of the fragment is talking about social classes or beings literally ‘cast’ from molten metal.

– Extract from Psychopomps & Heavenly Portals by Casper and Birgitta Andreassen.

Six years earlier

In a cupboard

Under a

Sink

Amber Altar Fox Bite orHeavenly Insects Dissolve Our Pain12

Cupboard Boy Blues

Taban is awakened by a burning in his throat and a stinging in his toe. In the corner where the moths dwell something glimmers. A tiny being. Six gold wings wrap around its body like a cocoon. It hangs upside down – its gnarled twig-like leg hooked into a crack in the door. It sways in front of the keyhole, the only source of illumination in the cramped cupboard where Taban is imprisoned.

‘Hey,’ Taban whispers. ‘Did you nip me, little bug … person?’

Silence. The boy wonders if he is seeing things.

Then a single yellow eye pops out from behind the veil of folded wings.

‘No,’ says a voice that comes from all around. ‘A fox did that. Naughty creature. Comes and goes where it pleases. Bites who it pleases.’

‘Oh,’ says Taban. The drum of his left ear throbs. He’d had a bad infection when he was little. Doctors pulled a thick congealed candle of black blood-wax right out of his head. Ever since then his left ear hears – or rather feels – frequencies that others cannot.

‘Say,’ continues the being. ‘You seem sad. Why don’t you make a wish? I have a master – a king – in another world who can grant wishes even in this one. So long as they’re made sincerely.’

‘Would you please talk quieter, Sir? Ms Cowley might hear you.’

‘Only the selected can hear my voice, boy. No need to worry.’ The being flutters down from its perch – two wings flapping, four covering its face. It leans in close. A spindly cobalt-blue hand waves, beckons. ‘Why not make a wish? You can whisper if you like. So no one will hear.’14

‘No. I don’t want anything. Please go. You’re going to get me in trouble.’

‘My, my. This Cowley seems to cause you much discomfort. Why don’t I make her disappear? I can do that. As a demonstration. I get the impression there are a lot of people you’d like to—’ The creature clicks its silver-tipped fingers. ‘Disappear.’

Taban shakes his head, covers his ears. For a moment he thinks he hears a rasping bark-like chuckle behind him.

The little winged being backs away. ‘Perhaps now is not a good time. But, consider what I have offered. Should you change your mind, merely say so with all your heart. King Solomon answers all prayers. Farewell. For now.’

The creature bows and is gone – sliding through some curtain-like fold in the shadows.

Taban shivers. The pipe that digs into his back has gone cold. Someone is running the tap – probably washing the paint brushes. How long has he been in here? His mind always goes funny when it’s locked in this cupboard.

The school bell rings. The door unlocks.

Taban unfolds himself from under the sink and stands up. He dusts off the grit in his blonde hair and straightens up his grey school uniform.

‘I hope you have learned your lesson, Taban Grayson?’ Mrs Cowley scowls. ‘No more disrupting art class.’

Dressed in her usual funeral-black outfit, Ms Cowley is slim and has a mousey face that Taban has never once seen smile.

‘Yes Ms Cowley,’ replies Taban, his voice pitched at its usual near-monotone flatness. ‘I promise not to paint the ocean purple when the instructions say blue again.’ He does not bring up that the only reason he did this is because he is colour-blind 15and cannot see the difference between some purples and some blues. One time he had tried to explain his condition, but she got very angry and told him he was making up excuses. So the boy knows not to try reasoning with her.

Ms Cowley’s eyebrow twitches. ‘That defiant expression of yours is infuriating,’ she says. ‘Just because your mother is a teacher don’t think I won’t send you to be caned by the headmaster.’

Ms Cowley always finds these deep meanings in Taban’s face. He does not know what to do. It’s just his face. He doesn’t know how to make it move in a way that will please her.

Taban skirts past the other children – who are rapidly exiting the classroom – to his desk. It is an old thing. Still has a hole for an ink pot. That and two decades of graffiti. He lifts the lid and takes out his pencil case – checks it. Someone has snapped his colouring pencils in half. As expected. Eleventh time since Cousin Caleb moved away. He closes the case and puts it in his school bag. Then a soft, ‘What?’ reverberates around the classroom.

Taban turns to see Hilde, the only other child still in the classroom, staring at her feet.

Ms Cowley’s face is performing its most dangerous expression – betrayal.

Hilde is both a swot and good at sports. The latter should make her popular at Highveldt, but she is almost as unpopular as Taban. This is because she doesn’t talk much and when she does she is often blunt in a way people think is mean. And even though she’s more expressive than Taban she often chooses not to be – giving neutral looks when people expect smiles. Also she is a black girl with white parents – which the other kids insist is weird even after learning how adoption works and everything. And there was a nasty rumour going around that 16she was found in a coffin as baby. Which wasn’t true. It was a quarry – which is where they get metal and rocks.

Her, Taban, and Caleb all used to be friends.

Since Caleb moved away she’s stopped talking to him.

Such is the way.

‘What do you mean you forgot your swimming costume?’

‘I really thought it was in my kit bag, Ms Cowley, I don’t know what has—’

Ms Cowley sweeps her hand as if pulling shut a little zipper on Hilde’s mouth.

The child falls silent.

Cowley smiles. ‘This afternoon was our last opportunity to practise before the Swimming Gala this weekend, Hilde.’ Her voice is gentle and calm. ‘Jackal House is behind this year and this event is our only chance to catch up. We’re hardly going to manage that if our star swimmer can’t remember her costume.’ Cowley closes her eyes, rubs her temples. ‘I expect this sort of carelessness from the other students,’ she adds, voice cracking a little. ‘But not you!’ She gives Hilde a strange look. Sad, angry, but full of affection. The sort of expression a more typical adult might make before forgiving a remorseful child.

Cowley snatches Hilde’s arm.

‘Taban, get the ruler.’

Taban pretends not to hear. He knows what comes next. He doesn’t want it to happen.

‘Taban!’

He crumbles. ‘Y-Yes, Ms Cowley.’ He runs to the teacher’s desk and fetches the wooden ruler from the top drawer. It is at least a generation old – numbers long since faded. Taban wonders if Cowley had, in her own school days, used this same ruler to draw straight lines where straight lines needed to be. 17

If he knew how to make a face that performed remorse Taban would do so. Instead he wears his usual neutral mask as he hands Ms Cowley the ruler. She takes it, raises it, slowly guides it through the air until it is just above Hilde’s arm – like a golfer preparing a swing.

Hilde scrunches her face, squirms.

‘Girl! Look at me! Look at me!’

She complies. The two lock eyes. Ms Cowley’s expression is wistful, nostalgic. It seems like some small light of mercy might break through its hardness. Instead a low growl rattles up from her throat.

‘You stupid!’ Crack.

‘Stupid!’ Crack.

‘Girl!’ Crack.

Hilde flinches with every strike.

‘Remember your swimming costume this weekend.’ Ms Cowley releases her raw, red arm. ‘Now get going!’

‘Yes, Ms,’ says Hilde, bolting out of the classroom.

A part of Taban wants to run after her, wants to say, ‘I’m sorry.’

A tiny part even wants to add, ‘I love you,’ – a phrase he hasn’t said aloud for a long while.

The boy used to say, ‘I love you,’ to his friends and family all the time. Because it is true and something he feels. But a little over a year ago he said it to Caleb in front of some older boys Caleb was trying to impress and Caleb became so angry that he did not talk to Taban for over a week. Taban had asked his mother why this was. She explained that it was not so much what he had said so much as how and when he had said it. That as he grew older he would understand when it was okay to say, ‘I love you,’ and how to say it in a way that wouldn’t disturb or 18embarrass the people he loved. Based on this information, Taban concluded that he should simply not tell anyone he loved them until he was absolutely certain he could do it properly. Now the words sound strange – dying in his chest before they reach his lips.

Such is the way.

He nods and leaves as if it didn’t happen.

He pretends it didn’t happen.

It didn’t happen.

Caleb wouldn’t have let it happen.

As Taban is about to step out the door, Ms Cowley’s voice pins him in place. ‘Taban, before you go …’ The words are spoken slowly, quietly, with the confidence of someone who knows they do not need to project their voice to make their audience listen. She bites a loose strip of skin from her nail, and then continues. ‘I’ve passed along what you said to Headmaster Horlick and we’re going to put a stop to it. Thank you for speaking up. One thing we absolutely don’t tolerate here at Highveldt is bullying.’ She suddenly claps her hands together. As she pulls them apart moth dust and moth limbs fall to the floor. ‘Bloody pests!’ she says, waving her hand to dismiss him.

As soon as Taban steps outside the room, a hand shoves his face against the red-brick wall of Room 32B and holds it there. The hand in question belongs to Hendrick Eugene Boeker. Hendrick has sea-green eyes and blonde hair. He’s very athletic. His father was once a professional rugby player. His four older brothers all excel at sport. Rugby, cricket, soccer, swimming, cycling, running – the Boekers are good at all of it.

‘Howzit, Tabby! What colour is my uniform?’

‘Grey.’19

‘Sut! Wrong, it’s blue!’

‘It’s grey, Hendrick. Colour-blindness doesn’t work like that.’

‘Na, Tabby, it’s blue. Hey everyone! This is blue, right?’

Some other kids have stopped to watch. ‘Ja,’ says one of them, smirking. ‘Looks blue to me, Hen.’

‘You hear that, Tabby – it’s blue.’

Taban knows his only escape is to play along.

‘Okay. I guess it’s blue then.’

‘Stupid! Everyone knows it’s grey, Tabby!’

Some of the other children laugh. Others roll their eyes. They’ve seen this routine before.

Satisfied, Hendrick unpins Taban and walks off in the direction of the Central Grounds.

Taban’s face stings, bleeds. He closes his eyes, sucks in air, and flushes the event from his mind – squashing it down into some deep pit in his stomach.

It didn’t happen.

Caleb wouldn’t have let it happen.

He continues on his way – walking around the corner to the Southern Grounds where, ever since Caleb changed schools, he sits on the veranda outside the school library and eats his lunch alone. The veranda is made of blackish-grey stone that gets searing in the hot-dry season. It overlooks the Southern Grounds – a sparse patch of unkempt grass and paper thorns that gently slopes towards a fence shrouded in haggard bushes, beyond which are the school swimming pools.

It’s a desolate view. Apart from one small bit of green sprouting from the centre – an acacia sapling – branches spread like two open palms, raised to catch as if the sun was a falling cricket ball. Its bough is painted white to shield it from sunlight and the termites. Taban wonders if that actually works 20or is just a superstition. He’s been observing the tree for months – wondering if it will die. And, if it dies, could he tell just by looking?

He sits on the edge of the veranda and eats his potato chip sandwich – the only way he can eat chips because getting grease on his fingertips makes him anxious. He thinks of next Monday – the first day of the summer holidays when he will be going to the Mana Pools game reserve with his mom. There he will get to see his cousin for the first time since Caleb’s family moved out to the farm nearly a year ago. He can’t wait to talk to him. He needs to talk to him. He needs to tell him how things have changed. Maybe he will even figure out how to properly say that he loves him, that he misses him.

Taban hears footsteps. He turns to see Hilde emerging from the toilets next to the library. She looks like she’s been crying. She does not acknowledge him. Instead, she too sits on the edge of the veranda – a metre or so away. She picks up a stick and scratches pictures in the dry dirt by her feet. Taban has seen these pictures before. Back when they were friends Hilde had explained to him that these pictures were old Viking letters called Runes. She had found them in a book owned by her adoptive parents – who both taught at the university near Taban’s house.

As Hilde draws, sunlight bounces off the bruises blossoming on her arm – making them look shiny, rubbery.

Taban again feels the urge to say something – to indicate his regret, his sorrow. ‘I’m sorry the teacher hit you,’ he says. ‘I’m sorry I brought the ruler.’

‘Shut up,’ she replies.

Taban shuts up.

The scratches in the ground by Hilde’s feet are almost 21entirely a mystery to him. He does recognise this one symbol though → ‘<’. Hilde told him once that it means ‘injury’ or ‘pain’.

Around Hilde’s feet there are rows and rows of ‘<’.

Taban packs away his now empty lunchbox and leaves her to her runes.

After meandering for a minute, not really sure where to sit since his preferred spot was taken, he settles on the edge of the Central Grounds – sitting on one of the benches that line its southern perimeter.

A person that used to play with him and Caleb way back in Grade 1 is sat on another bench several metres away talking with Hendrick. Daisy. Blonde. Pretty. Outwardly normal – though back then she secretly liked to eat ants. She would spit on her finger and spear them – trapping them in her sticky saliva. Taban and Caleb used to help by riling up the nests with chongololo carcasses and drawing the insects to her. But then one day the teacher caught them and they all went home with red arms. After that she didn’t speak to them any more.

Once Taban had asked Daisy why she liked to eat ants. She said it was because they were alive and she liked living things. Eating dead things was gross – like filling yourself with death. She also confessed that one day she would like to eat a really big ant – the size of a baby if possible. To punch a hole through its eye, pull out its black-green guts, and devour it.

Taban’s toe begins to itch again.

< < <

An Omen Veiled In Moth Dust & Paper Clippings

That night Taban dreams that Ms Cowley disappears. That one day during school she vanishes in a cloud of moths, leaving only dust and scuffed glasses.

In the dream, the shy insects that inhabit the cupboard under the sink – the ones the other kids call gross, whose wings they rip off in fits of idle cruelty – swarm out of the cupboard and cover her head to toe. She is not bothered by this. She does not seem to even register their presence as she continues marking homework.

Then, one by one, the moths fly up and out of the window, taking pieces of her with them. The pieces of Ms Cowley look like torn bits of paper – flat, weightless, two-dimensional. Each one a puzzle-piece fragment. The gap between her eyebrows. The knuckle of her left index finger. Her right nostril. As the last scraps of her are removed, Taban thinks he sees relief on Ms Cowley’s face – which is now nothing more than an eyeball and some lips. She looks like she is achieving some blessed release. Taban also feels relief. Relief that he is not going to be put in the cupboard any more. Relief that he, Hilde, and all the other children will no longer get whacked with rulers.

When he awakes from this dream it is still dark out and he experiences three immediate sensations. The first: disappointment that the dream is not real. The second: a strange sense of shame about that disappointment. The third: the itch in his toe. He pulls the covers off his bed and in the moonlight spots a mark. An orange wound. Its edges are crisp and clear and glow like they have been drawn into his flesh with glittering ink. The wound is shaped like something he saw in a church once – when their neighbour and family friend, Eve, got married.

Like this →23

24Putting aside the hotly debated issue of whether the fragment predates the invention of cuneiform, what can be translated from the ancient fragment is deeply mysterious. The text has all the content of a great myth. In fact some of it even feels like quite precise, calculated echoes of Viking and Christian mythology. Shadows of Yggrassil, Fenrir, Loki. The apple tree of Genesis. Seraphim.

All the more perplexing that it would be found deep in the riverbed of the Zambezi – a continent away from the cultures most associated with these mythologies.

But the content of the fragment is not as inscrutable as its stylistic form.

It doesn’t read like a poem or religious verse, but like an instruction manual or engineer’s schematic. Dare I say that some parts even read a bit like a sales pitch? It implores the reader to build the gateway it describes and promises all sorts of heavenly boons. Eternal life. Universal knowledge. Etc.

At least most of it reads like this.

Parts of the fragment are overwritten. It’s as if someone hurriedly scratched something new on the tablet – like you might jot a note on an old receipt.

These parts are mostly unintelligible. But there is a fearful urgency.

These sections read like a warning.

– Extract from Psychopomps & Heavenly Portals by Casper and Birgitta Andreassen.

Red Spiral Fox Bite or On Your Naked Back, In The Heat of Alien Saliva26

Long Dogs Under The Hot-Eyed Heavens

The sun’s gaze sweeps over the ragged midday wilderness of the Mana Pools National Park. The air hangs hot and heavy over everything like a see-through plastic film. The Grayson family car weaves past a large pile of disintegrating animal shit. Taban’s not sure what creature it came from. Something big. Buffalo maybe? Or perhaps elephant? He hopes not. One year, at night, a bull elephant ransacked their camp and had to be driven away by rangers with rock-salt shells. ‘Old Gandanga’ was a known menace in these parts. Grown mad and violent with age, he’d been ostracised from his herd, and had taken to raiding camps for sweet-smelling fruit. Apparently, that’s just something that happen to old bulls sometimes. Taban recalls Gandanga’s eyes, lit up by campfire – sad, dark pearls in a roiling ocean.

The car makes a metallic gurgle. Something within rattles. Fourth time since they left Harare. This pea-green 1950s Beetle was not built for deep potholes and dirt-track roads. ‘It’s going to break down any minute now,’ Taban’s mother mutters. ‘Any minute now.’

Taban ignores this. He is staring out the window at the passing trees and imagining a different world: caverns of clear crystal deep beneath the earth spiral down in criss-cross patterns before coalescing in a vast hall, in the centre of which the molten core of the world is suspended – held in place by a network of lights that emit mysterious energies. Around this hovers a halo of floating platforms. Buildings shaped like globular stalagmites cover the surface of each. One by one people drip from the strange houses and gather in the streets. Men, women, some who are neither, all of dark complexion 28dressed in white robes. Together, in accordance with the morning ritual, they sing.

Is there a point to this ritual? Taban hasn’t seen that far ahead yet. It is just an idea – a lingering image that rises to the surface of his mind when things are quiet. He has a lot of ideas like this. He doesn’t know what to do with them. They leave his brain feeling clogged and slow. This one is reminiscent of a show he watched that morning. What is it called? Spartakus and the Sun Beneath The Sea. That was it. That old French cartoon had captured his imagination. Now his imagination has captured it back, cannibalised the bits it liked, without him even asking it to. His mind is greedy. It wants to swallow everything.

Taban’s forehead aches. His skull buzzes – as if a fly is trapped inside. He winces his eyes closed. When he opens them he sees a figure out in the bush. An animal. It looks a bit like a fox, but unlike any fox Taban has ever seen. Tall as a man. Unnaturally long and thin – as if its grey flesh and patchy white fur have been stretched over a skeleton that is not its own. Its mouth is wide – twisted into what looks like a smile. The animal stares unblinking at Taban. A command forces itself into his mind.

Become Conduit.

Taban tries to turn away from the window but his head is heavy, his neck stiff. It’s like he’s pulling against some magnetic energy.

Must look away.

He wrenches himself from the animal’s gaze. All around there is the sound of sporadic gushing wind. Then he realises – it’s not the wind but his breath.

His mother has stopped the car. 29

‘Taban, are you okay?’ she asks.

‘There’s something out in the bush.’

‘Where? I don’t see anything, my boy.’

Taban points out the window to the spot where he’d seen the creature. There is nothing there now.

A sickly iron taste lingers on his tongue. He puts a finger in his mouth.

Red.

His gums are bleeding.

< < <

Horned Up & Saintly Boy Blues

As they pull into the campsite, Taban is surprised that Caleb does not come to greet him and his mom. Only Aunt Gertrude and Uncle Athel are there smiling and waving as Ann parks the car. Gertrude wears the unspoken dress-code of Dehannas matriarchs – polo shirt, flip-flops, and cargo shorts. She has a glass of wine in one hand which she narrowly avoids spilling as she pulls Ann in for a hug.

‘How was the trip up?’

‘Okay. Was a bit worried that the car was going to crap out but it all worked out in the end.’

‘And Cormack?’

‘Oh. Yes. He couldn’t come. Work stuff.’

‘Typical. Your husband is a workaholic, Ann.’

The two women share a knowing look. Taban recognises that they are engaged in a performance where they pretend to not know the truth – that his father always finds an excuse to avoid these annual camping trips regardless of how busy things are at the recording studio. Ann once told Taban that this was because Cormack didn’t like the bush. During the war for independence there was an incident where he got separated from the other soldiers and ended up lost in the wilderness for several days. The experience ‘spooked’ him.

Uncle Athel, smiling, laughing, scoops Taban up onto his shoulder.

‘How is my boy?’ he asks.

Uncle Athel is a giant with long muscular arms, big hands, a bulbous nose, and thick eyebrows. His skin is tanned and veiny. He is dressed as ever in khaki shorts, a sleeveless vest, 31and a broad-brimmed hat. Indiana Jones as performed by the BFG – as Cormack once described him after a few beers.

‘I’m good,’ says Taban, ‘Where’s Caleb?’

Athel’s smile strains – like a ship that’s been rocked by a sudden wave.

‘He’s sulking!’ Gertrude points to a red two-person tent at the far end of the campsite. ‘Why don’t you go and say hi? Maybe you can snap him out of his sour mood.’

‘Okie doke.’

Athel puts him down and Taban darts in the direction of the tent on the very edge of the clearing. It is a long way from the big green tent that serves as the kitchen and the long blue one where Gertrude and Athel are staying. Even its entrance is faced away in an obvious statement of protest. One thing Taban appreciates about Caleb is his lack of subtlety – he isn’t difficult to read.

He unzips the tent and peers inside.

Caleb is lying on his back looking at a magazine with a half-naked woman on the cover. He looks different from when Taban last saw him several months ago. His limbs, while still gangly, are more muscular and his skin is almost tanned as brown as his thick bush of hair. The biggest change though is his expression. He is frowning. It is a sad, heavy frown that appears to have resided on his face for a long time.

‘Hey.’

‘Jasis!’ Caleb jumps up and quickly stuffs the magazine under his roll-up mattress. ‘Taban? It’s just you, is it?’

‘Yup.’

‘Yurrrrr. Don’t sneak up on me like that. If Ma had seen this I would’ve been in big trouble.’

‘Why? It’s just a magazine.’32

‘Ja, but it’s real naughty. One of the Grade Seven Prefects gave it to me.’

‘What’s so naughty about it?’

‘The girls in it are naked.’

‘So? Girls are naked all the time.’

‘Ah. When you’re older you’ll get it, Tab.’

‘You’re only nine months older than me.’

Caleb rolls his eyes. ‘Don’t worry about it. Anyway how have you been? How’s Highveldt?’

‘Rubbish.’

‘Oh.’

Caleb is silent.

Taban wonders if he is expecting him to elaborate, but doesn’t know where to even begin.

Caleb sighs. ‘Well it isn’t Saint Vitus so it can’t be that bad.’ He stands up, brushes past, and walks in the direction of the green kitchen tent. ‘Come, let’s get cokes.’

Taban nods. Before following after he looks in the direction of where Caleb has hidden the magazine. He feels a strange urge to rip it up.

< < <

End Of The Dino War

Bedtime. Back in the tent. Taban unpacks a box of plastic toys from his satchel and spreads them out in front of Caleb. The little electric light Athel engineered for them makes the toy soldiers and dinosaur figurines cast twisted, amalgamated shadows – plastic bodies merging into dark forms.

‘Do you want to play Dino War?’

Dino War is a game Taban and Caleb have been playing since they were six. Although it is less a ‘game’ and more a long-running collaborative story they act out with toys. Taban has aspirations of turning it into a strategic computer game one day with a campaign mode that would take the player through the key battles of the war.

‘Na.’ Caleb doesn’t look up from the comic he is reading. ‘Tab, that stuff is for dorks. Also the game is over. The green guys won.’

‘I was thinking we could begin again many years later with a twist – the Arcosaurs have now become corrupted by power and the surviving Terrorsaurs must redeem themselves by overthrowing them.’

‘Slow down. What does “redeem” mean? What does “corrupted” mean?’

‘They’re words from the bible. “Redeem” means “become good”, “corrupt” means “become bad”.’

‘You use too many big words. And didn’t we already make the Arcosaurs bad at one point?’

‘No, that was just when a spy had taken over their army from within.’

‘I can never follow your stories, Tab.’

‘Please, Cal.’34

‘No.’

‘Come on!’

‘No! Don’t whine. It’s weird when you whine in that robot voice of yours. You sound like a retard.’

Externally, Taban wears his neutral mask. Internally he is in pain. ‘Retard’ is the sort of thing Hendrick would call him. He packs away the box, takes a book out of his satchel, and curls up in his sleeping bag. But he can’t focus on the words. All he can think about is how weird Caleb is acting.

‘You talk differently now,’ he says.

‘How?’

‘You sound older.’

‘Ja, well at Saint Vitus you’ve got to talk like the big guys or you have a rough time.’

‘You sound like Hendrick and all the other bullies at school.’

‘Little Hen? Really? That guy? He didn’t seem so bad. Always nice to me. Anyway, God, you’re a wuss – just hit him and he’ll leave you alone. I know his type – all show. You don’t know what real bullies are like, Tab. Highveldt is soft.’

Taban feels an urge to reach over and put his hands around Caleb’s neck and squeeze. Then, as suddenly as the urge came it is gone, leaving only a lingering sense of shame.

‘Is it okay if I turn off the light?’ Caleb asks. ‘I’d like to go to sleep now.’

Taban wants to explain to Caleb how he is wrong. He wants to explain how much nastier Highveldt has got since he left. How isolated he has become. How much he misses him. How he wishes everything could just be restored to the way it was. How much he loves him. But he doesn’t know how to make a face that expresses that or a voice that rises 35