13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

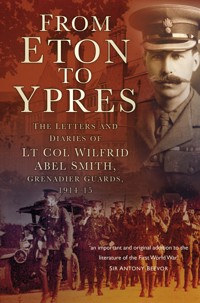

Regarded as one of the most outstanding commanding officers on the Western Front, Wilfrid Abel Smith commanded an elite unit of 1,000 of the finest soldiers in the British Army. Educated at Eton and Sandhurst, Smith was a career soldier who led his battalion of Grenadiers with distinction through the First Battle of Ypres and the winter trench warfare of 1914–15. He died of wounds received at the Battle of Festubert in May 1915. The letters and diaries provide a vivid, first-hand account of the fighting and suffering on the front line, written by a compassionate commander and affectionate family man. Most of his brother officers were Old Etonians, including his brigade commander, Lord Cavan, and his second-in-command, George 'Ma' Jeffreys. Smith's account offers a poignant insight into the way in which the privileged world of a Guards officer responded, with the highest sense of duty and courage, to the unprecedented demands of industrial warfare. From Eton to Ypres is edited by his great-grandson, Charles Abel Smith.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

To my children, Marina, Nicholas and Edmund, so thatthey and their generation may continue to remember

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to Lord Carrington for agreeing to write a foreword.

I must also record my thanks to Henry Hanning for all his support in helping me to produce this book. He is the last serving Grenadier descendant of Wilfrid and was for many years a regimental historian, publishing the much-acclaimed 350-year history of the regiment, The British Grenadiers, in 2006. Many thanks also to Robert and Anne Abel Smith for their support and encouragement.

Philip Wright, the Grenadiers’ Regimental Archivist, has been tireless in his assistance and I would like to thank him for his permission to print various extracts of his research together with photographs from the Grenadier Guards collection.

I am very grateful to Dorothy Abel Smith, John Abel Smith, Sue Kendall, Gordon Lee-Steere, Edward Gordon Lennox, Jane Jago, Celia Lassen, Jerry Murland, Michael Maslinski, Sir Timothy Ruggles-Brise and Mark Wagner for providing me with information about their forebears and allowing me to print letters and photographs from their collections.

In addition, I would like to thank Roddy Fisher, Keeper of the Eton Photograph Archive, for his help in providing me with photographs from the Eton collection.

I owe a debt of gratitude to Michael Leventhal for his faith in this book and the production team at The History Press, including Chrissy McMorris, Lauren Newby and Andrew Latimer, for turning it into the finished article.

Finally, a big thank you to my wife, Julia, for all her support in helping me to write this book.

Contents

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Wilfrid’s Family Tree

Abbreviations

Introduction

1 Wilfrid’s Early Days

2 Outbreak of War and Promotion

3 Wilfrid Takes Command of his Battalion

4 13 October to 22 November 1914 – First Battle of Ypres

5 December 1914 – Rest, Refit and Christmas in the Trenches

6 January 1915 – A Miserable New Year

7 February 1915 – Strengthening the Line at Cuinchy

8 March 1915 – Rest in Béthune and Transfer to Givenchy

9 April 1915 to 17 May 1915 – Strengthening the Line at Givenchy and the Emergence of New Hazards

10 Wilfrid’s Death at the Battle of Festubert

11 Wilfrid in Memoriam

Appendix

Bibliography

Biographical Index

Plates

Copyright

Foreword

I was invited to write this foreword because Lieutenant Colonel Abel Smith was a cousin of mine and I spent six years of the Second World War in the 2nd Battalion Grenadier Guards.

The letters and diaries of Lieutenant Colonel Abel Smith are a vivid reminder, more than 100 years since the start of the First World War, of the particular horrors of that conflict. Trench warfare must have been one of the most appalling manifestations of war and this comes over very clearly in Lieutenant Colonel Abel Smith’s diary entries. What also comes through clearly is the courage, stamina and determination needed through those long periods in the trenches and the resolution and discipline to keep going.

An example, on Christmas Eve 1914, he records: ‘We are in a beastly place. We took over the Indian trenches last night. It is all slush and water, in some places up to your waist. Tonight it’s freezing hard, to make it worse and plenty of bullets flying about.’

He must have been an outstanding commanding officer and a very brave man, as clearly demonstrated by the moving tributes to him from his colleagues and battalion.

Lord Carrington

29 September 2015

Wilfrid’s Family Tree

Showing Main Characters

Abbreviations

AA

Assistant Adjutant

AAG

Assistant Adjutant General

BEF

British Expeditionary Force

C. Gds

Coldstream Guards

CIGS

Chief of the Imperial General Staff

C-in-C

Commander-in-Chief

CMG

Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George

C-of-S

Chief of Staff

Coy

Company

DAAG

Deputy Assistant Adjutant General

d.o.w.

died of wounds

DSO

Distinguished Service Order

EEF

Egyptian Expeditionary Force

G. Gds

Grenadier Guards

GOC

General Officer Commanding

GOC-in-C

General Officer Commanding-in-Chief

GSO 1, 2 or 3

General Staff Officer 1st, 2nd or 3rd Grade

I. Gds

Irish Guards

k.i.a.

killed in action

MC

Military Cross

OC

Officer Commanding

Ox. L.I.

Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry

QMG

Quartermaster General

S. Gds

Scots Guards

W. Gds

Welsh Guards

Introduction

Wilfrid Abel Smith was regarded as one of the finest commanding officers on the Western Front. He took over 2nd Battalion Grenadier Guards in September 1914 whilst they were fighting on the slopes of the River Aisne. This had followed the first encounter of the BEF (British Expeditionary Force) with the Germans at Mons and the ensuing Battle of the Marne. His battalion was one of the elite units of the British Army with 1,000 of the finest soldiers the country could produce. It went to France in August 1914 with great optimism that the war would be over by Christmas. By the end of November, it had held the line during the First Battle of Ypres and, periodically reinforced, had suffered nearly 1,000 casualties. Thus began the stalemate and the horrors of the trenches, in which Wilfrid was to lead his men over the next six months until he died of wounds during the Battle of Festubert on 19 May 1915.

Had he survived that battle, contemporary accounts make it clear that he would likely have soon been promoted to brigadier general and given a brigade. His second-in-command, George Jeffreys, retired as a full general and his brigadier, Lord Cavan, rose to become a field marshal.

Wilfrid went to France aged 44, a father of three young children and a devoted and loving husband to Violet, granddaughter of Lord Raglan of the Crimea. A career soldier, educated at Eton and Sandhurst, he was the epitome of a Guards officer. He had enjoyed a privileged and comfortable life as the son of a wealthy banker. His soldiering had included the full range of ceremonial duties that would have been expected of a Grenadier, with the occasional foray into colonial wars and a stint in Sydney, as aide-de-camp to the Governor of New South Wales.

Wilfrid arrived in France to take over a battle-weary battalion under constant attack. His officers and men knew that they owed their surviving the retreat from Mons to his predecessor, who had been recalled home for retreating without orders, thereby saving the battalion from annihilation. Wilfrid quickly gained the deep respect of all who served under him.

In the midst of continuous fighting he managed to write to Violet most days, in the most challenging conditions. She compiled the volume of letters and diaries that form the core of this book. These were typewritten and bound by John & Edward Bumpus, Ltd in 1917. Although correspondence from the Western Front was heavily censored, Wilfrid was remarkably frank. He painted a vivid picture of the constant shelling and trench conditions through the winter of 1914–15. As a professional soldier, he carried out his orders to the best of his ability, but he was rarely complimentary about his high command. He respected his professional German adversary, but was disgusted at the way in which the Germans conducted their war. He despaired at the loss of the men under his command and of the many friends and relations who fell before he did.

There were some moments of light relief: the arrival of gifts, such as a cake from his children, or a pheasant from his sister-in-law, was always welcome in the mess. Visits by the Prince of Wales to the battalion were something to write home about, particularly when he managed to fire a shot at a German or was conveying a delighted German officer prisoner of war in the back of his car.

England was not far away. Wilfrid was able to get The Times the day after publication. As a soldier on the Western Front, he was interested in the other theatres of war. His increasing frustration with Churchill’s ill-fated campaign in Gallipoli is clear. Developments on the Eastern Front were also closely followed.

Wilfrid chronicles a nine-month period during which the western world experienced fundamental change. The industrialisation of war saw the annihilation of Britain’s professional army. Violet had to deal with the implications of this at home, and constantly worried about her husband. This was an age of nascent technology, which we now take for granted: the development of aerial and submarine warfare, the use of chemical warfare and the beginning of electronic communications. Cavalry charges and the sword became redundant and Britain found itself on the front line with the threat of attack by airship. The need for industrial-scale munitions production brought about labour unrest and helped bring down the British government.

Britain and the rest of Europe would never be the same again.

As a commanding officer, Wilfrid assumed responsibility for his nephew, Desmond Abel Smith, who later considered that he owed his survival through the war to his uncle. Wilfrid’s letters describe how Desmond was sent out to his battalion in December 1914. He was transferred to another Guards regiment en route and Wilfrid describes how he fought hard with his high command to get him back. Desmond was swapped for another subaltern, who was dead within a month. His account of his uncle’s death describes the loss he felt.

Wilfrid’s letters to Violet do not convey the full horror of war, as he wrote them in a matter-of-fact way so as not to alarm her unduly. I have included letters that he wrote to fellow soldiers that describe the brutal reality of the front more vividly and complement his battalion diaries. His accounts of the First Battle of Ypres have been much quoted. He records his deep disapproval of the 1914 Christmas truces that were made on other sections of the line but not his. He experienced some of his most difficult trench combat over this period. I have incorporated quotes from historians of the war to complete the picture.

As would be expected of a commanding officer of the Grenadiers, Wilfrid had very high standards and was a strict disciplinarian. But his letters also show a deep sense of compassion for his men and a desire for their advancement. His leadership inspired a devoted following shown in the condolence letters that Violet received after his death.

Wilfrid was a devoted father and wrote regularly to his children. It was not easy carrying out the role of father from the front. His letters clearly mark the holidays that he missed with them. Wilfrid’s understanding and support comes across strongly, no more so than when he writes to his eldest son, Ralph, about coming bottom of the class, when his younger brother, Lyulph, had done rather better. But he did not shy away from telling his sons what he expected of them and how they should support their mother over Christmas while he was away. Wilfrid’s letters to his daughter, Sylvia, highlight the love that he felt for his children and for the family dog, an Airedale terrier called Jack. He treasured the letters he received from his children, the last of which was found in his pocket on the day he was fatally wounded. Ralph’s account of being fired at with corks from a friend’s anti-aircraft pom-pom gun must have lightened the mood in battalion HQ.

In transcribing Wilfrid’s letters, I have sought to retain his punctuation and abbreviations, only amending them to make it easier for the contemporary reader to follow. His letters to Violet only contain the text that she had transcribed in 1917. His other letters have been transcribed in full.

I have got to know Wilfrid well. I wish I had known him in person. His letters remind us of the sacrifice that he and so many others made, and that we and future generations must never forget.

1

Wilfrid’s Early Days

Wilfrid Robert Abel Smith was born at Goldings, near Hertford, on 13 September 1870, the eighth of twelve children and the third of five sons of Robert and Isabel Smith. Robert Smith was a successful banker descended from Thomas Smith of Nottingham, who founded the first English provincial bank in about 1658. Smith, Payne and Smith was well known in the City of London with premises at 1 Lombard Street. Robert was a God-fearing, philanthropic banker of the kind more often to be found in Victorian times than in the present day. Born in 1833, he had married Isabel Adeane in 1857, when she was only 18. The young couple lost no time in producing a large family. Their first child was born nine months and three days after their marriage. At the age of 30, Isabel found herself with eight children. Four more were to follow by 1879. There were six to nine years between each of the surviving four brothers, one having died at the age of 9, so it seems that none of them will have been at the same school together.

Wilfrid spent his infancy at the old house at Goldings in the village of Waterford near Hertford, where he had been born. When he was 6, the family moved into the enormous new Goldings built higher up the hill away from the damp of the river below. This house still stands but has been divided into apartments. It was designed by Thomas Devey, one of the most successful but least-known domestic Victorian architects. It is described by Mark Girouard in The Victorian Country House as ‘One of Devey’s largest and most depressing houses’.1

Robert did not undertake this project until he had built Waterford’s first parish church in 1872, where there is now a memorial to Wilfrid. He employed Morris & Co. to fit out the church’s interior and it contains one of the finest collections of Pre-Raphaelite stained glass with windows designed by William Morris, Edward Burne-Jones and Ford Madox Brown.

Wilfrid followed his two elder brothers to school at Cheam, near Newbury (according to his mother, ‘the only good private school then in existence’),2 and then to Eton and the Royal Military College at Sandhurst. It was at Eton and Sandhurst that his ears apparently suffered from battering in the boxing ring, resulting in some deafness; it was a characteristic (the deafness, not the boxing) later possessed by his daughter Sylvia and her son. He was fond of music and took up the cello.

His taste for a soldiering career was almost certainly sparked by his father’s younger brother, Philip Smith, a tall, finely built bachelor who had a distinguished career in the Grenadier Guards and retired as a lieutenant general. Philip was close to Robert and Isabel and would have seen much of the children. In 1882 he took the 2nd Battalion of the regiment (which Wilfrid was himself destined to command) to Egypt where, under Sir Garnet Wolseley, the expedition scored a startling victory at Tel el-Kebir over a far superior force of insurgents by a brilliant little battle lasting thirty-five minutes. One can well imagine the pride and delight of the 12-year-old nephew at the triumph of his uncle, who was rewarded with a CB (Companion of the Order of the Bath).

Wilfrid’s Lent Term school report from Eton in 1885 gives little indication of the 14-year-old’s true potential. Whilst he came first out of thirty-two, his class was Division XVIII, so his peer group would have been amongst the least academic of his year group. His conduct report read, ‘a terrible fidget: lacking in power of concentration: very fairly punctual’, and his overall summary was, ‘Deserves credit for steady industry, often against the grain. Is not a clever boy, and takes a long time in mastering new ideas, but retains them well when he has made them his own. Ought to make more effort to get the better of his flightiness.’

Wilfrid’s Eton school report, Lent 1885, when he was 14. (Author’s collection)

Wilfrid’s exam results at Sandhurst suggest that he was not a candidate for the Sword of Honour (his marks placed him at the top of the bottom quartile for his year), but his riding prowess earned him a special certificate of proficiency. He was commissioned into the Grenadiers in 1890, joining the 1st Battalion in Dublin and moving the following year to London. He spent the following seven years in and around the capital. His adjutant (a ‘head boy’ role responsible for the young officers) was Charles Fergusson, a fierce and terrifying man later to reach great heights, who would have seen that Wilfrid behaved himself and learned his business swiftly and well. That apart, he must have had a wonderful time.

It was a good life for anyone fortunate enough to have been born into a prosperous family when the British Empire was at the height of its confidence and prestige, and never more so than when fashionably placed in society. Military duties were humdrum, largely confined to ceremonial, administration, sport and home-grown entertainment. From time to time, there were camps for rifle shooting (described as ‘musketry’) and marches and manoeuvres still conducted in scarlet tunics and bearskin caps. Leave for the officers was plentiful and could amount to several months of the year so long as it was spent in developing military virtues of courage and skill in the hunting field or killing pheasant and grouse. Dinners, balls, levées and parties of all kinds were numerous. Wilfrid returned to Goldings often and there were other fine houses to visit. His fun, however, will have been much marred by the death in 1894 of both his father Robert and his uncle Philip (his mother lived until 1913).

Curiously, though he used ‘Abel’ as part of his surname in bookplates and elsewhere, his military records invariably show him as W.R.A. Smith. His wife was always ‘Violet Smith’ or ‘Mrs Wilfrid’. It was the succeeding generation that first adopted ‘Abel’ as a matter of course. His bookplate also identifies his chosen profession as a soldier with a bearskin and a sword in the bottom right-hand corner.

Wilfrid’s first service abroad came in 1897, when the 1st Grenadiers went to Gibraltar. They were refused permission to take bearskin caps. Whilst the stay cut short Wilfrid’s shooting season at home, it gave him the opportunity to go after different quarry from the usual fare of pheasant, partridge, hare and rabbits. His game book records a five-day shooting expedition to Seville and the River Guadalquivir in search of bustard and geese with two fellow officers, the Hon. Edward Loch and Edward Verschoyle. Wilfrid was to write to Loch’s sister, Lady Bernard Gordon Lennox, seventeen years later following the death of her husband, Lord Bernard Gordon Lennox, during the First Battle of Ypres.

Wilfrid recorded at the end of the trip:

The weather throughout was glorious, just like June, and we all enjoyed it enormously, the only blot being that Verschoyle never hit a thing the whole time. He was very seedy and had jaundice badly when we got back. We had to pay 1 Peseta for each bustard and 30 cents per goose to get them into Seville, and 10 pesetas to get them onto Gib. It was a great trouble, but they kept well and ate first rate. Total 57 Head.

The first real excitement arrived in 1898, when Wilfrid’s battalion was given notice to join Kitchener’s Sudan expedition, designed to bring an end to the persistent Dervish activity and to avenge the death of General Gordon in 1885. Kitchener achieved his purpose in decisive fashion. The 1st Grenadiers travelled up the Nile by rail and riverboat, arriving at Omdurman where, on 2 September, at derisory cost to the British and Egyptian force, over 10,000 Dervishes, mostly armed with primitive weapons, were mown down by rifle, machine gun and artillery fire without getting anywhere near the firing line. What part did Wilfrid play? In 1973 an account of Omdurman was published by Philip Ziegler, who asserted that, at an early point in the battle, there had been a messy and inglorious scuffle in front of the line between a Dervish and one of Kitchener’s staff, ‘Lt Smith of the Grenadiers’.3 Not so. The offending officer was Smyth of the Queen’s Bays, who was rewarded with the Victoria Cross. Wilfrid was in charge of the battalion transport and looking after mules in the rear. But it must have been exciting nonetheless. Press cuttings of the campaign, including several drawings, were collected at home and Wilfrid later pasted them into an album which survives.

The following extracts from a letter that he wrote to his mother on 5 September 1898, following the fall of Khartoum, give a flavour of his experiences on the expedition:

My dearest Mother,

So it’s all over and our flag is once more over the Government House at Khartoum side by side with the Egyptian flag. We had a desperate fight, it lasted five hours, and is said to be the biggest fight ever fought in the Soudan. I suppose you will want to know all about it, and as I have nothing to do and time hangs rather heavily on our hands, I will tell you a certain amount …

At 6.45 by my watch the first shell went, and then for an hour and 50 minutes we fought. Their first line came rather to the right of my Battn. led by the Kalifa’s son. As soon as they appeared the Artillery began. Their first shot went too far, the second a little short, the 3rd got them exactly over the big banner carried by the Kalifa’s son. Down went the banner and Heaven knows how many men. I saw all this beautifully through my glasses, and then I had to set to work getting up ammunition, as the Battn. began to do a bit of execution. At last they retired and we got ready to advance. They never came nearer to us than 700 or 800 yards …

The Town stinks worse than any place I could imagine, and if we stay here long I am afraid there will be a lot of sickness …

Not long after returning home, Wilfrid was given a plum appointment as ADC (aide-de-camp: personal assistant) to the Governor of New South Wales. This was the only time he served away from his regiment and it had momentous consequences. The Governor, William Lygon, 7th Earl Beauchamp, was, at 27, younger than his own ADC. A glittering political future was forecast for him and he had been appointed to acquire some experience of public service (as it happened, it was later discovered that he was rather too fond of liveried footmen and his prospects collapsed in ruin).

How Wilfrid came by the appointment is not clear but such affairs were often handled on a personal basis and he will certainly have known Beauchamp’s younger brother, Edward Lygon, a Grenadier who was fated to be killed in South Africa in May 1900. Comfortably installed at Government House in Sydney, Wilfrid was responsible for the Governor’s personal and social affairs. The seating plan for a large dinner in January 1900, written in his own hand and including his own name, was on show to tourists in 2012. His time in Australia involved travels across the continent and a visit to New Zealand in March 1900. Here Wilfrid experienced the traditional welcome, the Haka. He was also able to enjoy the novel experience of shooting godwits at Onehunga, a port on the edge of Auckland.

A visitor arrived in the form of Violet Somerset, Beauchamp’s cousin and the daughter of the 2nd Lord Raglan. In the beautiful gardens and Scottish baronial splendour of the Government House, she fell in love with the ADC and he with her. They were engaged on 17 September 1899. A handsome portrait was painted in Sydney of Wilfrid as a captain. Promotion could be very slow as it depended on vacancies being created by death or retirement.

Wilfrid returned home on 1 November 1900 and on 3 December he and Violet were married at Holy Trinity Church, Sloane Street, by the Reverend John Mansel-Pleydell, his brother-in-law. The honeymoon was spent at Goldings, at Longhills near Lincoln with his second brother Eustace and his family and at Normanton near Nottingham, one of the seats of the Earl of Ancaster, before they settled in London.

Violet’s diary for 1901 is a delightful record of some of the joys and agonies of a young bride, as well as a few of the great events of the time: 22 January – ‘Queen died at 6.30 pm. Wilfrid shot at Papplewick.’ Wilfrid’s game book recorded a bag of fifty-nine for the day. It was his last day of the season and his summary of it read: ‘Did not get home from Australia till 1st Nov. and so got no shooting to speak of.’

Violet’s husband’s routine does not seem to have been more irksome than in earlier years, but when Wilfrid had to spend nights away on guard or in camp, she wrote, ‘Oh how I miss him,’ though he wrote to her every day and sometimes also sent a telegram. They lived quietly though many visits were made and returned and they enjoyed a variety of London entertainments. Wilfrid’s younger brother, Bertram, was a frequent visitor and the two hunted together when in the country. Curiously, there is no mention of the tragic death of his eldest brother Reginald and his 13-year-old nephew Cyril (Reginald’s son) in that year. There was cello in the evenings (Violet was a good pianist), piquet and even the new game ‘bridge’.

He often went to work by bicycle, which did him credit in an era when an officer of the Guards was not supposed to be seen on a bus or carrying his own shopping. On occasion he would ride to Goldings while his wife travelled by train. The first evidence of their possessing a car comes in 1903, when Wilfrid’s accounts show a new category of expenditure, ‘Motor’, starting with an entry of £179 12s paid to Locomobile Co., for the purchase of a car.

And despite the ominous news on 18 December, that ‘Wilf was told that he is to take the next draft to S. Africa next month,’ Violet’s diary ends with, ‘What a happy year 1901 has been,’ followed by a memorandum, ‘House-parlourmaid, Annie Smith, Bladon, £20 a year, 1/6 washing, no beer’.

On 16 January 1902, Wilfrid sailed from Southampton to South Africa to join the 3rd Battalion. The Boer War had already been running for over two years and both the 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the Grenadiers had been out for most of that time. But the battles of the early months, which had often proved more painful for the British than for the Boers, were long past and the war had become a matter of manning strongpoints, blockhouses and barbed-wire lines along the railways, and launching drives to round up the Boer guerrillas while their farms were burnt and their families moved into the now notorious concentration camps.

Wilfrid’s company was responsible for a part of the railway line. It attracted little attention from the hard-pressed Boers, who made peace on 1 June. Wilfrid is recorded as having left for England on 27 June, which was fortunate as the main body of the battalion was not home until October, having been away for more than three years.

In July 1903, back with the 1st Battalion, Wilfrid was appointed Captain of the King’s Company, traditionally containing the tallest men in the regiment. This was a coveted post that he held until the end of 1906 and would have been approved personally by the king. One of his albums records Wilfrid being received by the king on 27 June 1905 and presented with ‘a pair of Sleeve Links bearing the Badge of the Company’. In fact, the only special role for the company was to find the bearer party at a monarch’s funeral and thereby attract some little glory for its captain. Wilfrid would no doubt have reflected somewhat ruefully on the timing of his tenure, which lay squarely between the deaths of Victoria in 1901 and Edward VII in 1910, but he had the consolation of a coronation medal in 1911.

During this time the family started to arrive: Ralph in 1903, Lyulph in 1905 and Sylvia in 1908. At some point they moved to Upton Lea in Slough (telephone Slough 62).

On relinquishing the King’s Company at the end of 1906, Wilfrid was promoted major and went again to the 3rd Battalion. Here he stayed for eight years, until the outbreak of war in August 1914. War clouds were gathering well before that time and training had taken on a new urgency. There were reforms in the army. Fitness and discipline were further improved. Long marches were frequent. Above all, the sharp lessons taught by the Boers were learnt and shooting skills reached a level that was probably never to be surpassed. They were to be needed in spades.

Wilfrid was a meticulous man and kept detailed accounts of his income and expenditure. His first account book is dated 1883 when, aged 13, he would have started at Eton. His banker father presumably encouraged him to account for his money from an early age. The 1883 accounts itemised the money he received throughout the year, mainly from his father, which totalled £19 10s. His later accounts provide an interesting insight into the lifestyle of a Guards officer of the day. In 1907, his net army pay as a major was £411 10s 10d, an amount comparable to what a major would earn in 2015. Out of this he had to cover regimental expenses of £137 12s. These included £2 2s for a wedding present to Lord Bernard Gordon Lennox (who was to die on 10 November 1914 in the First Battle of Ypres). The net balance of his army pay covered only a small proportion of his family’s living expenses, which totalled £1,568 4s 6d. A Guards officer required a significant private income. Perhaps the most surprising significant category of expenditure was ‘Subscriptions’ which, at £162 18s 10d, accounted for over 10 per cent of the family budget. While this included subscriptions to a large number of regimental and sporting clubs, together with The Travellers Club, nearly £100 was paid out for life insurance. Wilfrid’s accounts go into great detail, itemising, under ‘Sundries’, numerous purchases of dog biscuits, a dog collar and chain and even a drill book, which cost 3s.

Notes

1. Girouard, Mark, The Victorian Country House (London and New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1979), p. 407.

2. Abel Smith, Dorothy, And Such a Name …: The Recollections of Mrs Robert Smith of Goldings (Knebworth: Able Publishing, 2003), p. 89.

3. Ziegler, Philip, Omdurman (London: Collins, 1973), p. 162.

2

Outbreak of War and Promotion

On 9 September 1914, Wilfrid was promoted lieutenant colonel and appointed to command the 2nd Battalion in France. At the time of his promotion, he was Senior Major (second-in-command) of the 3rd Battalion, where he will have been largely occupied in drawing in and training reservists. This battalion remained in London until the formation of the Guards Division in July 1915, though many of its members would by then have been sent to make up for the heavy casualties incurred by the other two battalions. The 2nd Battalion (known in the regiment as ‘the Models’) had been one of the first to go out in the BEF in August.

Michael Craster explains in Fifteen Rounds a Minute that:

This was not quite an ordinary Battalion of course. The Brigade of Guards, the modern Household Division, did not have a monopoly of discipline, smartness and professionalism in the BEF, but as an élite they did believe in the highest standards in all three, believe in them, demand them and maintain them, whatever the cost. They might be matched, but never beaten … Approbation was not given lightly, either within or without the Brigade, but when given it was well merited …1

Formed in 1656, the Grenadiers are the most senior regiment of foot guards. They have a friendly rivalry with the Coldstream that goes back to the Restoration of Charles II. The Scots Guards, who trace their origins back to 1642, are the third regiment of the original guards trinity. The Irish Guards were still very new, having been formed in 1900 by order of Queen Victoria to commemorate the Irishmen who had fought for the British Empire in the Boer War. They had seen their first action at the Battle of Mons in August 1914.

Whatever their regiment, men of the Brigade of Guards felt a common bond as members of what was, in effect, a large family. The officers formed a close, tight-knit community and many could count numerous generations of service in their family. They knew each other well and were frequently related. Wilfrid’s letters talk about his nephews, cousins and friends in the Grenadiers and other Guards regiments. Only guardsmen could command guardsmen and they would happily respond to orders of any officer in the Brigade. The Guards had a very strong tradition of welfare for their men, a concept not common at the time. Officers were trained to put the comfort of their men before their own personal needs.

Guardsmen came from a wide variety of backgrounds. Their minimum height restrictions and strong sense of discipline made them fearsome adversaries. Their effectiveness as soldiers was further enhanced by their loyalty to the regiment and an unrivalled pride in their conduct and appearance that went beyond simple discipline. By the beginning of the First World War, soldiers could sign up for three years of service followed by a commitment to serve for nine years in the reserves. Britain had a relatively small standing army of about 250,000 men at the beginning of the war but the reserves enabled battalions to be brought up to fighting strength very quickly in August 1914.

When war came to Britain on 4 August 1914, the 2nd Battalion was at Wellington Barracks. It was well trained and its equipment was all ready when mobilisation orders were received. By 6 August, nearly 3,000 Grenadier reservists had reported, been examined, clothed, armed and equipped, and joined their battalions.

Training was still being carried out and the king and queen came down to the gates of Buckingham Palace as the 2nd Battalion was returning to barracks from a route march. The men marched past in fours and saluted the king, their colonel-in-chief. The battalion, then commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Noel Corry with twenty-nine officers and 1,000 men, crossed over to France on 12 August. It disembarked at Le Havre and marched out of the town to an overnight camp 5 miles away. The following day it entrained to begin the journey to the outskirts of Mons to meet the German threat.

A Grenadier Guards private holding up his 1908 pattern webbing ‘marching order’. This consisted of 150 rounds of .303 ammunition in the front pouches, water bottle, entrenching tool (on his right), haversack, bayonet and entrenching tool handle (on his left). The pack with great coat, ground sheet and personal items is in the centre. (Grenadier Guards)

The 2nd Battalion marching past Buckingham Palace, watched by the king and queen. (Grenadier Guards)

Lieutenant Colonel Corry leading 2nd Battalion out of Le Havre. (Grenadier Guards)

The BEF, which went to France in August 1914, comprised about 86,000 men in two army corps, under the command of General Sir John French. The 2nd Battalion Grenadiers was placed in 4th (Guards) Brigade with three other battalions, 2nd and 3rd Coldstream and 1st Irish Guards. The 4th (Guards) Brigade was one of the three brigades of the 2nd Division under Major General Charles Monro. This division was one of two in I Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General Sir Douglas Haig.

Military Units during the First World War

Unit

Composition

Commander

Army

Two or more corps

General

Corps

Between two and five divisions with supporting arms and services

Lieutenant General

Division

Four brigades plus artillery, engineers and support services, totalling 12,000–20,000 men

Major General

Brigade

Four battalions, approximately 3,000–4,000 men

Brigadier General

Battalion

Building block of the army: four companies, 1,000 men at full strength

Lieutenant Colonel

Company

Subunit of a battalion, usually about 250 men

Major or Captain

Platoon

Subunit of an infantry company. Four sections of about sixteen men

Lieutenant or Second Lieutenant

Section

Subunit of an infantry platoon, usually about sixteen men

Corporal.

In the first few months of the war, the battalion took part in the confusion of the withdrawal from Mons, the 190-mile march to south of the Marne achieved in two weeks under the late August sun and the cautious pursuit of the German Army to the Aisne.

After the Marne, the battalion’s commanding officer, Noel Corry, had been sent home. Judging correctly that his battalion had been told to hold an untenable position at Mons, and that he had a better understanding of the situation than his commanders further back, he had courageously defied his orders and withdrawn his men. Happily, he was later vindicated and given another command in 1915.

Philip Wright, the Grenadiers’ Regimental Archivist, describes the patrolling on the Aisne:

Fighting on the steep heavily wooded slopes of the Aisne valley eventually congealed into trench warfare with the armies of both sides locked in the mud of their static positions. ‘No man’s land’ between the trenches was covered in unburied bodies.

The trenches were gradually improved and deepened despite intense shelling from field guns and heavy howitzers. Rabbit netting was procured from the neighbouring woods and converted into wire entanglements. Raids were periodically made to stalk the enemy’s snipers hidden in trees, haystacks and wood stacks, which had been hollowed out and loop-holed. The skill of the highly trained soldiers with the Lee Enfield .303 rifle – fifteen aimed rounds a minute minimum (the so-called ‘mad minute’) – was used to great effect, although the losses sustained by the battalion were also considerable.

Two patrols on the Aisne within a few days of each other illustrate both the effectiveness of this rapid firepower, which the Germans often mistook for machine guns, and the initiative and resourcefulness of the junior NCOs in command.

Lance Corporal P H McDonnell led a patrol with two men to reconnoitre a small wood a few hundred yards in front of the battalion lines. They discovered a large party of about thirty Germans in an advanced trench at the forward edge. The enemy thought they had captured the three men and began to walk forward to take them prisoner. At this point McDonnell gave a sharp order to fire and the resulting hail of bullets from the patrol caused a considerable number of casualties. Before the Germans could recover from the confusion the three Grenadiers had escaped. McDonnell was awarded the DCM. His citation read: ‘On 27th September made a first class reconnaissance and discovered an unsuspected German trench.’ He later transferred to the Welsh Guards (formed in 1915 largely from Grenadiers, Wales having been a regimental recruiting area) and was promoted to sergeant.

The citation for the DCM awarded to Lance Corporal W Thomas is more detailed: ‘On 1st October went with three men through a wood to burn a wood stack from which sniping took place, and meeting a patrol of fifteen Germans fired at them and drove them off. After waiting they went on and successfully lighted the stack.’ The battalion war diary records that two Germans were killed and that Thomas himself was badly hit. He was subsequently promoted to sergeant. On 3rd December, the King, accompanied by the Prince of Wales in Grenadier uniform, inspected 4th (Guards) Brigade at Méteren. It was his first visit to the front and he presented DCM medal ribbons to McDonnell and Thomas and five other members of the Battalion.

Thomas was killed in the trenches a few days later on Christmas Eve 1914 and is buried in the Guards’ Cemetery, Windy Corner, Cuinchy. An extract from a letter sent to his sister by the men of 4 Platoon of 1 Company reads: ‘He was killed instantly by a shot in the head on the afternoon of 24th December. It may be a relief to you to know that he died fighting to the last. The Germans were in our trenches and he barred the way shooting down every man that came his way. He saved many of us and we greatly sympathise with you in your loss.’

Wilfrid, as his Commanding Officer, wrote to Regimental Headquarters: ‘You will be sorry to hear that Sergeant Thomas was killed the other day. He got the DCM for good work on the Aisne and never received the medal. He came out as a Private and has worked his way up to Acting Sergeant by sheer merit. He was a gallant man and a great loss to No. 1 Company.’2

In his letter of 10 December, Wilfrid sent Violet a copy of the battalion’s diary for the first half of September before he took command.

DIARY

2nd BATTALION GRENADIER GUARDS

September 1st, 1914 To September 18th, 1914

Sept 1st

Marched from Soucy 4 a.m., fighting rearguard action. Hotly engaged at Villers Cotteret, 4 Officers Missing, 2 N.C.O’s [sic], and Men w., 122 Missing. Halted at midnight. Bivouacked in parts of Betz and La Villeneuve.

Sept 2nd

Marched at 2 a.m. Halted for breakfast at 9.30. Marched to Rolenter, near Meaux, and bivouacked.

Sept 3rd

March at 7 a.m. to Pierre Levée, and occupied position on Pierre Levée-Ligny Road.

Sept 4th

Marched at 9.30 a.m. Battalion engaged. Marched to La Bertrand, arriving at 11 p.m., and bivouacked.

Sept 5th

Marched at 5 a.m. to Fontenoy. Halted at 10 a.m. for 2 hours. Bivouacked at 3 p.m.

Sept 6th

Marched at 5.30 a.m. to Tonquin. Bivouacked at 8.30 p.m., and entrenched.

Sept 7th

Marched at 4 a.m. Halted at 9.30 a.m. to 2.30 p.m. Battalion joined Advanced Guard. Bivouacked at …

Sept 8th

Advanced at 8 a.m. Battalion engaged in wood fight. Stephen and 18 w. Bivouacked 8.30 p.m. near Les Peauliers.

Sept 9th

Ready to advance at 5 a.m. Moved at 9 a.m. about half a mile, and halted till 1.30 p.m.

Bivouacked at Domptier about 8 p.m.

Sept 10th

Ready to advance at 5.30 a.m. Moved at 7.30 a.m. Bivouacked 8 p.m. at Breuil.

Sept 11th

Ready at 5.30 a.m. Marched at 7.15 a.m. Very wet.

Battle of the Marne, position of the British Army on 8 September 1914. (Ponsonby, Vol. I, p. 46)

Sept 12th

Ready at 5 a.m. Marched at 9 a.m. Marched 3 miles and halted till 12 noon. Advanced and billetted at 8 p.m. Very wet.

Sept 13th

Ready at 5 a.m. Marched at 8.30 a.m. Attacked position after heavy Artillery fight. Advanced and billetted at 8 p.m. Very wet.

Sept 14th

Advanced at 5.30 a.m., and crossed the Aisne at Pont Arcy by pontoon bridge. Battalion took and held position near farm La Cour de Soupir, after a heavy fight. Entrenched and remained in position.

Des Voeux and Cunliffe k. Gosselin, Walker, Mackenzie, Stewart, Vernon, Welby w. 17 k. 67 w. 77 m.

Sept 15th

Remained in position – heavily shelled.

Sept 16th

Remained in position – heavily shelled.

Passage of the Aisne, 14 September 1914. (Ponsonby, Vol. I, p. 58)

Sept 17th

Relieved by Oxford L.I. [Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry], and billetted at Soupir.

Sept 18th

Relieved the 3rd Battalion Coldstream Guards at La Cour de Soupir farm at 4.30 a.m. Entrenched.

· BACKGROUND NARRATIVE ·

Wilfrid corresponded with his three children, Ralph (then aged 11), Lyulph (aged 9) and Sylvia (aged 5) throughout his time on the Western Front. In September, they went to stay in Deal. Ralph and Lyulph soon went to their boarding school, West Downs, near Winchester, and Sylvia stayed in Deal until December:

Sept 8th 1914

Sandown Road

My dear Father

We arrived about 6.00 yesterday. There is a cruiser and a gun boat guarding the coast here, and there is a hospital ship here too, we saw a wreck on the Goodwin Sands today, it had four masts, and we saw the coast of France too. We could see the light ship on the Goodwin Sands. We heard the guns at Dover, and saw the harbour. There are eleven thousand sailors outside Walmer Castle. It was very hot here yesterday, but it is much cooler here today. They say that they have not had much rain here since the first of August. There were wrecks here last month two of them were Spanish ships. There were three German ships here yesterday, but there is only one here today. Cargo ships are passing here all day going to Dover. There is a very big pier here. We went on the beach before breakfast for twenty minutes this morning. We are three minutes’ walk from the sea here. Everybody thinks it is quite safe here, because of the Goodwin Sands. There is no sand here, but only big and small stones. It is very shallow water here, and seems quite safe for bathing, as people bathe all day here, and some at 5.00 in the morning. Lyulph and Sylvia send their love to Mummie and you.

Your loving son

Ralph

Notes

1. Craster, Michael, Fifteen Rounds a Minute: The Grenadiers at War 1914 (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 2012), pp. 2–3.

2. Wright, Philip, For Distinguished Conduct: Warrant Officers, Non Commissioned Officers and Men of the Grenadier Guards awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal in the Great War 1914–1918 (London: Blurb Publishing, 2010), pp. 15–17.

3

Wilfrid Takes Command ofhis Battalion

Wilfrid travelled to France with the Earl of Cavan, a Grenadier friend, who was taking command of the 4th (Guards) Brigade. Cavan, Viscount Kilcoursie, had joined the Grenadiers in 1885, after attending school at Eton. He served with the 2nd Battalion in South Africa and had no ambitions beyond a command in his own regiment. This he achieved in 1908, when he was given command of the battalion. He retired from the army in 1913 and became Master of Foxhounds for the Hertfordshire Hunt. He was recalled at the start of the war and was given command of the brigade succeeding Brigadier General Scott-Kerr, who was wounded on 1 September at Villers-Cotterêts.

As Henry Hanning explains in The British Grenadiers:

it was the view of Sir Henry Wilson that [Cavan] ‘doesn’t see very far, but what he does see he sees very clear’. It was by no means a bad verdict, for nothing could have been more important than clarity of vision, particularly in the desperate days of autumn 1914 …

In September 1915 he was appointed the first commander of the new Guards Division, though he did not approve of the concept. He was horrified to hear that all four Grenadier battalions were planned to be joined together in a single brigade and managed to persuade Kitchener against the idea. He also refused to allow the division to be put into another assault on the Somme in November 1916, saying, ‘No one who has not visited the trenches can know the extent of exhaustion to which the men are reduced.’1

Cavan was promoted in 1916 to lead XIV Corps, which fought first in France and then on the Italian front. In 1922 he succeeded Sir Henry Wilson as Chief of the Imperial General Staff and was appointed field marshal later that year. He retired in 1926. His nickname ‘Fatty’ reflected, in good army tradition, the fact that his physique was very much the opposite.

On the Aisne, the 2nd Grenadiers had been led by their second-in-command, George Jeffreys, a man of outstanding capacity and determination. Jeffreys was the son of a rural landowner in Hampshire and descended from the brother of the notorious seventeenth-century judge of the same name. His nickname ‘Ma’ was derived from a Mrs Jeffreys, known as ‘Ma’, who had kept a house of ill repute in Kensington in the 1890s.