Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: BoD - Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

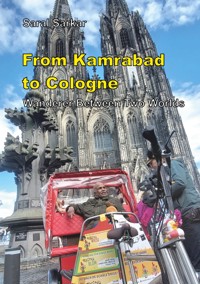

In his autobiography, Saral Sarkar takes us along on a journey through his interesting and eventful life. He is one of the few persons who experienced the first full half of his life in a poor third world country, India, and the other half in a very developed European country, Germany. And he experienced these two countries intensively. Unlike so many other immigrants, he did not come to Germany for economic reasons, but initially, in the 1960s, because of his love for the German language (being trained there as teacher for German), and then later in the 1980s he stayed there because of his love for his wife Maria Mies, a famous German feminist and sociologist. From an early age, he was very interested in political issues and movements, initially mainly from the left spectrum, but later (from the early 1970s on) his concern for ecological issues came to the foreground. The famous book The Limits to Growth (from 1972), which influenced an entire generation and served as an important impetus for the ecology movement, was also a turning point in his personal thinking. He experienced the rise of the green movement (and the Green Party) in Germany at first hand, but also left the Greens in disappointment in the second half of the 1980s. But it was not only political activism that shaped his life. From the 1980s onwards, he became an increasingly prominent author on environmental and political issues, with his two major works: "Eco-Socialism or Eco-Capitalism? A Critical Analysis of Humanity's Fundamental Choices" and "The Crises of Capitalism - A Different Study of Political Economy". It is no exaggeration to say that he is one of the most important contemporary thinkers on eco-political issues; one who coined the term "eco-socialism" in a consequent and clear way.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 365

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To Biggi and Jakob (Brigitta and Jakob Perings),

without whose multifarious help in leading my everyday old-age life, with Maria and alone, writing this autobiography would not have been possible at all.

Table of contents

Preface

Chapter 1: Childhood, Fatherland, Motherland, Family Background

Chapter 2: Growing Up, Coming of Age

Chapter 3: Going to College, Becoming Political

Chapter 4: The Great Disillusionment

Chapter 5: Going to Germany

Chapter 6: Arrival In Germany

Chapter 7: As Student in Munich

Chapter 8: Back To India – Via Egypt

Chapter 9: Fifteen Years in Hyderabad – Part 1

Chapter 10: Fifteen Years in Hyderabad – Part 2

Chapter 11: The Last Five Years in Hyderabad – Prelude to Living in Germany

Chapter 12: Living in Germany – Part 1

Chapter 13: Living in Germany – Part 2

Chapter 14: The Plagues of Old Age

Chapter 15: The Last Days of Maria

Chapter 16: My Life After Maria’s Death

Preface

Now that I have finished my last serious book*, but am still living, some of my friends have been telling me that I should now write my memoirs or my autobiography, whatever I would like to call it. I have been hesitating, because I am now 88 years old, and my health is fragile. I do not know how long I would still live, nor how much time I still have to write about my modestly eventful life. Nor do I know whether my life-story would interest anybody. These friends say it would, because I am, as they express it, a rare person who has spent half of his 88 years long life in India – in spite of all economic development, still a poor and backward country – and half in Germany, one of the richest and most modern countries of the world. I have experienced, have had intimate knowledge of, life in the East and the West, in the North and the South. I have taken part in political and social movements in both, thought, studied and written about these. One of the friends said, history should better be written by people who lived it.

I have now acceded to their pleadings, started writing this life story. I have nothing else to do, so why not. I cannot possibly commit suicide out of boredom. But, in my mind, the doubt remains: Will it be regarded as just a pastime of an old man? I remember Nirod Chaudhury, a Bengali intellectual, much more known in his active days in his native West Bengal than I am today in Germany or even Cologne. Chaudhury wrote his autobiography – at which age I do not remember – and called it "Autobiography of an unknown Indian". Maybe he was too modest or only pretended to be modest. But the title encourages me. I think I have also many interesting political matters to narrate about.

I have given much space to my childhood, because it lies now so far back in time, more than 80 years. It is as if I am describing a journey to an almost different, till now unknown country. Moreover, my nephews and nieces and their children ask me often about my childhood days. They are eager to know about their heritage.

But I have not neglected to describe the thorny road I have had to traverse to reach my present life and my present thoughts and conclusions. I hope, apart from being interesting, it would also be useful for all young and old political activists.

Finally, I want to remind the readers that an autobiography is not an history of the particular decades. It is the story of the decades as perceived by the author. It is mainly centered around his life-story. The quality of the story depends entirely on the quality of the perceptions of the author.

And just another word, with age, my memory has also blurred a lot. Many details, which could have been interesting, are missing. I hope the sympathetic reader will excuse me for this shortcoming of the text.

Last but not least, I want to take this opportunity to express my heartfelt thanks to my Viennese friend Ernst Schriefl, who has edited and typeset this text, not only this text, but all my other writings that have seen the light of day since August 2023.

* Sarkar, Saral (2024): Factors of Conflict and Conditions of Peace. An Essay, Books on Demand

Chapter 1: Childhood, Fatherland, Motherland, Family Background

My early childhood was not so interesting. I was born as the fifth child of my parents. I cannot say whether I was a desired child, because my parents already had two sons and two daughters. Nowadays, we would think, already the fifth child is going to be a burden. In Germany, in the recent past, I have often heard, having a child is a “poverty factor” (“Armutsfaktor”) – in Germany, one of the richest countries of the world. A few years ago, I read a report on 10 young German women who wanted to have a child, but could not find a suitable young man as a willing partner. But I do not know how people thought in those days – be it in India, be it in Germany. Apparently, in India as well as in Germany, children were regarded as products of God’s wish. They had therefore to be welcomed, gladly or grumpily.

When I studied German and later married Maria, my German fiancé, I came to know more about the situation in Germany in those days. Maria, born in 1931, was the seventh child in a small peasant family of 12 children. I, in contrast, also a product of the 30s of the 20th century, belonged to a six children family.

In my childhood, our family consisted of six children and the two parents. That was the average family size around us. When I was eight years old, I came to know families that consisted of as many as ten children, two parents, and one or two grandparents. And, moreover, some relatives, near or distant, used to live as members of the family. In our family too.

In an average family, children used to be brought up carelessly, and often sons were treated very badly, they were even beaten by the fathers, sometimes even by the mother, for allegedly bad behavior. I cannot say, probably my eldest brother and my eldest sister were treated lovingly. After all, they must have been well desired children. But I do not remember having ever been taken on my parents' arms or cuddled by some of my parents and elder siblings.

Father’s Land

My father came from a family that originally lived in what is since 1971 called Bangladesh. They were administrators by tradition; his father was employed in the administration of a tax-collecting landlord (Zamindar) of East Bengal. The village where they lived was situated roughly at the confluence of two great rivers – the Padma, which is the name of the main arm of the Ganges when it passes through East Bengal, and Yamuna, which is the name of the other big river which comes from the North-East, i.e., Brahmaputra.

River scene in Bangladesh. Photo credit: Saral Sarkar

Together, they transport the whole rain- and snowmelt on both sides of the Himalayas and Northern India to the Bay of Bengal. In the dry summer months, they are fed by the Himalayan glaciers. Try to imagine a village in such a location in East Bengal in the year 1900, when my father was born. There were no dikes on the banks of the two great rivers. That meant, every year, in the rainy season, as a matter of routine, the village and all the surrounding areas were flooded by the waters of the two rivers. My father told us how they went to school (just primary school, of course) wading through flooded village roads/pathways. The mud-hut buildings, [clay-built] big or small, in which they lived, of course, were built on raised platforms, also built of mud [clay], so that they were not flooded. Children who went to school, before they came down on the flooded village pathways, had to take off their clothes and hold them on the head, so that they would not get wet.

My father also told us, that peasants in their region planted a special species of rice that grew in height simultaneously, when the water level on the fields rose, so that the ears of corn always remained above water. The corn generally ripened before the water had receded from the fields. And the peasants had to do the harvesting in knee-deep water.

Before I could see with my own eyes one of these two mighty rivers of my home country (Desh, Pitribhumi, in Bangla; Heimat, Vaterland, in German), I had the opportunity to see the two “mighty” rivers of Western Europe: the Rhine and the Danube. I saw the Rhine already as a student in Germany in the 1960s. And now I am living in Cologne for the last 42 years. Impressive, of course. But then, sometime in the 1990s (I have forgotten, in which year exactly), Maria and I had an invitation from a best female friend of hers, a native of Bangladesh (Farida Akhtar), to visit her and her NGO establishment in Dhaka and the adjacent rural areas, where their development projects were located. I expressed the wish to see one of the two mighty rivers of my fatherland (“Desh”). They fulfilled this wish of mine on our way back from one of their projects. I stood on the east bank of the river Yamuna. On the west bank was my “desh” (fatherland), the region where my father came from. It was afternoon of a clear sunny day in late August. Yet I could not see the west bank. There was nothing but the river in front of me, a vast expanse of water. It was as if I was standing on the shore of a peaceful sea. It was almost the end of the rainy season. Our hosts told us, when the water level goes down at the end of the rainy season, one can see some large uninhabited sandbanks (called “Char” in Bangla) in the middle of the river. These Chars were probably not just useless sandbanks. They must have been useful for something, maybe for cultivating melons. For I heard from one of our young “uncles” (a relative of father, who came to live with us) that big landlords used to try to occupy Char-lands when they emerged. Often their respective “armed” groups fought it out.

From the unsystematic and rare narrations of my father, some relayed to me by my eldest sister in later years of my life, I could gather that life at the confluence of the two large rivers had another problem, namely, the two rivers used to gnaw away land at the banks. Oftentimes, whole villages (or parts thereof) were eroded away by the currents of the two mighty rivers, and the residents of the destroyed villages had to move further away from the banks and build new houses. Sometime in my childhood, I heard a song on this phenomenon – composed, however, by a city-dwelling poet. The first two lines of the song read: “The river breaks this bank and builds up the other. That is the game of the river.” From the narrations of my father, I could further gather that the family lived in three different villages in that region: Kurhigram, Bagmara, and Sonapadma. The reason, I guess, was this phenomenon of erosion. Once he also spoke of a huge fire that destroyed their house. No wonder, in those days, the houses in Bengal villages were mostly thatched with rice straw.

Father did not tell us (or I did not get it) in which of these three villages he went to his first school. But one story I vividly remember. It was surely about going to the secondary school. His elder brother was already in secondary school in the town nearby. I cannot say exactly in which town that school was. Maybe it was called Rangpur or Berhampur. Both are situated in North Bengal. My grandfather had to send money to the elder son for his school, boarding, and lodging expenses. He once asked my father, the younger of the two sons, to bring the cash to his elder brother in the town where this school was. My father resented that only the elder son was sent to the secondary school and not he too. After reaching the town (let me suppose it was Rangpur), he said the money was for both the brothers to go to school. Father did not go back home after that, stayed back in the town and went to the same school.

There, father used to tell us very proudly, Kalidas Roy, who later became somewhat famous as a poet, was one of their teachers. I remember having read a poem by this poet as a part of our reading material on Bangla literature. Many years later, when father had retired from service and we had settled down in Calcutta, he heard that also poet Kalidas Roy, had left East Bengal and was living then as an old man in Calcutta. Father took up contact with his former teacher. He also invited poet Roy to the party he gave on the occasion of the marriage of his eldest son, my eldest brother.

I did not get it directly and clearly, but somehow, mostly by asking my eldest sister, who knew more, that after finishing high school, father went to college in the town of Berhampur. He did his intermediate arts (a certificate after 12 years of school) there. After that he emigrated to Calcutta, like his elder brother before him.

I do not know exactly whether he did a B.A. degree course. If yes, it was at a short-lived National “University” which was founded by the leaders of our independence movement. But I do not have any clue as to whether he could also complete that course and get his degree. I guess not. Anyway, such a B.A. degree would not have been recognized by anybody.

My uncle, father’s elder brother, did indeed get his B.A. degree from the University of Calcutta and became a school teacher. He had a very interesting episode in his career, which I heard from my mother: In the far west of India, in the province of Punjab, there was a shortage of graduate teachers for the schools that were being newly founded there. So, a delegation came from the town of Hissar to Bengal to recruit a headmaster for a school there. My uncle, who was an ordinary teacher, accepted the offer, and went to Hissar. That must have been in the 20s of the 20th century. In the distant Hissar, my uncle and his wife must have felt very lonely among the Punjabi population. So they invited his brother, i.e. my parents, to visit them. I did not hear much from my mother about these holidays in Hissar, except that it was an adventure and everything was at the beginning so strange. My uncle apparently did not relish that job as a headmaster and came back to Bengal to again become (I guess) an ordinary teacher.

My father’s career also had been interesting. As a young man, he had to start doing something. His first profession was teacher of spinning and weaving. He had joined the independence movement as a volunteer. Under the leadership of Gandhiji and in the wake of the Non-Cooperation Movement, people were to be inspired and taught how to spin yarn from cottonwool and to weave cloth that could be made into self-made “swadeshi” clothes. I did not get to know whether it was a paid job, nor, if paid, who paid his wages. In pursuance of this vocation, he had to go to several villages. And in one of these, called Dakshin Barasat, he saw my mother, then a 15 – 16 years old girl, with whose eldest brother he became friends.

The Non-Cooperation Movement did not result in India winning independence from British rule. What happened then is part of India’s history, but what I want to tell here is what happened to my father. He went back to Calcutta. What he did then I did not get to know. One thing I heard from father himself was that he was working as some sort of a salesman or sales agent. Of which company and for which products, I did not get to know. Many years later, when, as a boy, I was rummaging in an old trunk containing useless things, I found pieces of skins of leguaans. Father was probably an agent for an exporter of such things.

The next thing I heard about his efforts to make a livelihood was that he found a job as a cashier in a company called Indo-Swiss. This job gave him, it seems, a little stability and security in life, and he started thinking of marrying. Then, the next thing I heard was that he met mother's eldest brother who had become a friend. He told this man, Kalidas Chaudhury, that he wanted to marry his sister, whom he had seen in their Village (Dakshin Barasat).

Mother’s Land Dakshin Barasat. Her Family Backgrounds

I had the opportunity to see my mother's home village, Dakshin Barasat, for the first time when I was nearly 8 years old, and several times later on. It was (is) connected to Calcutta by railway. It took in 1944 about one hour train travel from Calcutta to reach that village. In the first trip to the village, it was already late afternoon when we reached it. On the way to our mother's ancestral home, I had the first glimpse of the village. It was a foot march on narrow pathways between ponds – a pond on the right and a pond on the left. Later I came to know that all villages in southern Bengal were villages of many ponds. I would understand later why it had to be so. Southern Bengal was the huge low-altitude delta area formed by the silt content of the waters of all the rivers of northern India that flowed into the Bay of Bengal. In this area, whenever one wanted to build a house, one had first to dig out earth from a place, use the same for building a raised platform and then building one’s house. The byproduct of the exercise, a large hole, was soon filled up with ground water and rainwater in the rainy season.

The ancestral house of my mother was a solid two-story burnt-brick house. One of our maternal uncles was living in one part of it, with some other relatives who were living in their own households in other clearly designated parts thereof. On arrival, we children were very tired. After having our evening meal, we soon fell asleep. Waking up next morning, the first thing I heard was that Dilip, my brother, who was only two years older than I, had sighted a snake that was lying across a step of the stairs and prevented him from going to the ground floor. Somehow, the snake was made to give way.

Next day we started learning about life in a southern Bengal village. That was necessary, because in the nearly eight years that I had till then lived in this world, I, also my siblings, had always lived in towns of northwestern India, where my father had been working as a government employee. The learning was especially necessary, because a week or so later, we had been scheduled to go to another southern Bengal village, called Kamrabad, to live there permanently in our own house.

Let me here close the gap in the narrative that has opened up, because I am not following a strictly chronological order in it: After marrying, my father worked for some more time in the same company, Indo-Swiss. But then his in-laws thought that this job in a small private company was not good enough and did not give any job-security, which was and still is very important for a married man in India.

How he got it I do not know, but his next job was some sort of an accounts clerk in the military accounts department of the central government. It offered job security and prospects of rising up in the hierarchy, but it had the disadvantage that the employee could be transferred to an office of the same department anywhere in India. For this reason, father, and along with him his whole family, never in our early youth had a really settled life anywhere. In the course of the first eight years, I remember and heard, I lived in six different towns: Meerat, Jhansi, Ramgarh, Danapur, Patna, and then in the village Kamrabad – the first three in Uttar Pradesh, the next two in Bihar, and the last one in southern Bengal.

The first lesson came the next morning. My brother Dilip told me that there was no toilet in the house, that people had to go to the bamboos forest near the house to empty their bowels. He further said, while doing his shitting, he was visited by a fox. He was afraid, but succeeded in shooing it away. I was surprised, and afraid too. But I also had to go to the bamboos forest. All the houses, in which I had lived till then, had an old-style pit toilet in the farthest corner of the inner courtyard. We were used to that system. But that was all in towns, some in cantonment towns, no foxes, but many swine from the poor people’s quarters. But Dakshin Barasat was a village in southern Bengal, in the midst of thick lush greenery. For years thereafter, this trouble was the main reason for my reluctance to go to the maternal uncle’s house. Later, however, I was told that grown-up women of the house did not have to go to the bamboos forest. For them there was a separate arrangement in the house, which I too would be allowed to use.

The second lesson I learnt there was that one takes a bath in a pond and not in a bathroom. The villagers had selected two or three ponds with relatively clean water for that purpose – one for men and children, and another for grown-up women. One or two deep-dug wells were also there in rich people’s houses. Water from them were used as drinking water. It was common tradition that owners of such wells allowed their neighbors to draw drinking water from them. One was not fussy about neighbors entering the courtyard and have a free view of the inner parts of the house.

It may be in this first week of my life in southern Bengal that I learnt basic swimming. But it may also have been in Kamrabad, where we subsequently went to live in our own house, which father had bought.

But let me first finish the story of my mother’s family backgrounds. She was born in a quite educated family. The railway connection and the location in the vicinity of Calcutta – in those days still the Capital of the British Indian Empire – made it possible for her father and the uncles to get modern western higher education. Her father graduated as an engineer from the most renowned engineering college of those days (Shibpur Engineering College). One uncle became a chemist, and another a school teacher, whom we often saw when he, as a very old man, visited his niece, my mother.

My grandfather, the engineer, was sent to the Shal* forests of southwest Bengal to work in the project to build a railway line there that would connect that region with Calcutta. He went there with his family and lived somewhere near what is known as Jhargram. My eldest uncle from mother’s side (her eldest brother) told us that his father, being the engineer-in-charge of the Jhargram section of the project, got from the railway company an elephant as means of transportation along with a driver (the mahut). He also remembered that his father often took his son along on elephant’s back when he went to the work site. He was very proud that in the railway station building of Jhargram, a portrait of his father still hung as the builder. Mother’s chemist uncle used to make talcum powder for the women of the house.

The good luck of the family ended however with the sudden death of the father. The widowed mother returned with the children to Dakshin Barasat. There they managed to survive. How? – I could not get to know that. Maybe they just became part of the extended joint family, as was (still is) the traditional social security system of India. My mother was sent to her maternal uncle’s house in south Calcutta (Ritchi Road, Ballygunge) to grow up there with the children of the family. There she went to school to get some primary literacy education. Her three brothers did not get any high school education, or they could not finish it. I do not know why. All three learnt a technical trade – the older two became electricians, the youngest became a radio mechanic. Such qualifications must have been in great demand in those days, when application of these technologies was spreading in Calcutta. And, as I wrote above, Dakshin Barasat lay in the vicinity of Calcutta. These maternal uncles took charge of all the electrical work in our house, when father bought a half-finished house in south Calcutta (Ballygunge) and shifted home from Kamrabad to Calcutta.

I must here also narrate the story of my maternal aunts. My mother had good luck. It was my father who proposed to marry her. But her two sisters, being daughters of a penniless family dependent on relatives, were not so lucky. My eldest aunt, mother’s elder sister was married to a widower, who already had a daughter from his first wife. But for mother’s younger sister, although she was a very beautiful woman, her relatives could not find a suitable match. My father, the son-in-law of the family, was also trying. And it was he who found, believe it or not, a “prince” who was willing to marry her. It was a “prince” of “Shovabazar.” His father was actually a very big rent-collecting landlord (zamindar), who had command over the land of several villages, but who lived in Shovabazar, a locality of old Calcutta. Such landlords used to be given the title “raja” (king) by the British, whose king in London was the Emperor of India.

This prince had in his youth lived as an ascetic monk. That meant only that he did not marry, but he was rich and carried on with his high lifestyle in a villa in Dehra Dun (on the foothills of the Himalayas). But later he did want to marry and start a family-life – at what age, I did not come to know, nor did I ever ask. The couple did not get a child. My eldest sister told us that, as a child, she had spent 3 to 4 months in the house of this couple. From mother I heard that they wanted to adopt her as their child. But my parents did not agree. What remained from this sojourn in the mind of my sister were happy memories and a life-long penchant for a beautiful life-style, which she later always missed in our ordinary middle-class household.

This prince-uncle of ours died relatively early. So our aunt became a widow. She left Dehradun and came back to West Bengal and thereafter lived in Howrah, the twin city of Calcutta, where a brother of hers also lived. She must have been a rich widow, having inherited her deceased husband’s property. But I did not come to know how rich. We visited her once or twice, and she showed us two very thick albums of postage stamps of many different countries and a collection of coins of different countries. She often visited us in Kamrabad. And even I, still a child, could see that she put on airs.

My father had no sisters, or they may have died very early. But we came to know a cousin sister of his. Her fate was also mixed. She too was bestowed in marriage to a relatively rich land-owning widower in a village of West Bengal. This man already had 6 children from his first wife, and he fathered six more with this second. I heard from father that he had two brothers. About his elder brother I have written above. But a younger brother died in his boyhood. He had climbed a tree to pluck some fruits. And he got bitten by a red ant of a vicious type, whereupon he lost his grip, fell to the ground, got severely injured and died.

Generally speaking, in those days in India, in the absence of modern medicine, people used to die early. Octogenarians were quite rare, I think.

Kamrabad

Before we shifted to Calcutta, we lived about three and a half years in Kamrabad. These years gradually formed my consciousness. I started noting things and happenings around me more intensively. I became aware of many things, also became politically aware, and developed political sympathies and antipathies. Unknowingly, I also became worried about the ecological predicament of mankind. But I shall come to these points a little later.

Kamrabad was not a poor village. Because of job and small-business opportunities in Calcutta, there were (or had been) quite a few well-to-do families there. That could be seen in the numerous well-built burned brick houses (although many were somewhat dilapidated). Two houses were very big. One was, however, shared by many families. But higher education was a rare commodity.

My father was a respected person because of his professional status of a higher-level central government officer. There was, in those days, just another college-educated person in that village, who was very proud of being a graduate.

My mother too was a respected person, but for other things: for her tailoring and sewing skills, which were totally lacking in the village. She also did some social work in that she offered to the local girls to teach them sewing. I remember them meeting on the roof terrace of our house for the purpose. I do not remember whether she already had her hand-driven sewing machine in Kamrabad or got it in Calcutta. But I remember some poor neighbors occasionally coming to her and requesting her to do some tailoring work for them.

In such a village, relations between neighbors could not but be very informal. Our house, like all other neighboring houses, was an open-access one. That is, the compound doors of the houses were never closed to visitors except in the night. Anybody, immediate neighbor or not, could enter the house compound and come up close to the veranda, where they always met somebody or the other from the usually large families. Or else, they would simply call out for the chief of the household.

Our house was particularly open in this sense. It was situated in the middle of the locality where we lived. And the pathway from one corner of that locality to the diagonally opposite corner was around a few houses and a big pond, making it somewhat longer than the diagonal distance between the two corners. Since our house had two compound doors – one at the front and one at the backside of the compound, and both were open from morning to evening – people who wanted to go from one corner to the other made a shortcut through our house compound. Sometimes, even strangers made use of it. We, having earlier lived in towns of Western India, were not used to so much openness. I remember I told mother of this unusual thing. But she had learnt about this a few days earlier and told me we have to tolerate that. This was a traditional right of all people including strangers.

Like all south Bengal villages, Kamrabad too was full of ponds. We also owned a pond with foul water, but only half of it. The other half belonged to another house. This pond was full of two-three special kinds of fish that apparently thrived in foul water. Here I discovered (by observing other boys) the technique of angling, which I at first did not understand. I made a fishing rod with a bamboos twig and some thread from mother’s sewing box. Then I tied a small and thin piece of wood at the far end of the thread. When I first used this self-made fishing rod and hoped that some fish would remain hanging on it, nothing happened at all. Again, it was my mentor Dilip who explained the technique to me. Later on, we both became “expert” anglers.

My brother Dilip (left) and I. Photo credit: Saral Sarkar

Apropos of foul ponds of the village, they of course belonged to some house, but it seemed to me that they too were open-access things. Once a poor man came to our house with some foul-water fish (maybe caught from our pond) and requested mother to “buy” them in exchange for some rice. Otherwise, he said, he would have to grow hungry that day. Mother had to “buy” them.

My father developed our living standard a little, because it was embarrassing for mother to use our pit toilet in the outhouse situated at a distance of some 15 meters from our house. He let a sanitary closet built attached to our house. He also let a borewell dug on our courtyard so that we could always have clean drinking water. This latter action had the side-effect of increasing the number of neighbors who visited our compound.

Like our uncles’ house in Dakshin Barasat, our house in Kamrabad too had a house snake. When I first saw it, I had already learnt that not all snakes were dangerous. Our house snake was a nonvenomous one. But it had the bad habit of lying straight across the doorway on the backside of our compound. We were not afraid of it, but we did not dare disturb its sleep. So we had to jump over it when we wanted to go to our garden. Actually, snakes were ubiquitous in south Bengal villages. My father told us, once a snake even crawled through the kitchen of his in-law’s house in Dakshin Barasat, when he was taking dinner there sitting on the floor. The snake was apparently chasing a mouse. That was of course in the 1920s or 1930s.

In Kamrabd, under a big banyan tree, there was a small temple of goddess Sitala. She was worshipped regularly on particular days. It was said that she guaranteed protection for the devotees against small pox, which was in those days a deadly epidemical disease. The vaccine against the disease was already there. But some people did not have faith in it. For protection against it, they relied more on consecrated water from the Sitala temple.

During our residence in Kamrabad, we became witness to a tragic failure of goddess Sitala. A neighbor who had absolute faith in the efficacy of the consecrated water from the temple, had always refused to get his family vaccinated. But this time, the water failed him. The two eldest children of the family died of the disease. A third child, a teenage daughter, survived, but was left with a face full of pockmarks. Most people in the village had however got themselves vaccinated. Nothing happened to them, but that did not mean that they ceased going to the Sitala temple. There was no harm in having oneself doubly protected.

In Kamrabad, I also witnessed a case of practice of magic. Somebody in the village had lost something valuable. He thought it had been stolen and suspected that the thief lived in the village. He requested some magic practitioners to find out the thief. When I heard of the event and rushed to the courtyard where it was taking place, it was already in progress. Two grown-up men were playing (so it seemed to me) with two ca. 4-metres-long pliable pieces of bamboo (which were made by longitudinally splitting a bamboo into 4 equal parts). One of them was holding in his hands one end each of the two long bamboo pieces, the other man the other two ends of the two bamboo pieces on the opposite site. Both men were forcefully pushing the bamboo pieces toward the other side, as a result of which the bamboo pieces were bending and twisting and making otherwise funny movements. When after sometime this “play” came to an end, one of the two “players” said with a grave face that he knew now who the thief was or rather the house from where the thief came, but that he could not say that, because the family was known to many. The whole thing appeared to me to be a damp squib.

Scene from rural India. Photo credit: Saral Sarkar

An attraction of Kamrabad was a snack stall in a thatched-roof mud hut. It used to be opened only on Sunday mornings. Its proprietor was an old emaciated man. He was called Bhonda Ghosh. He must have had a proper first name, but hardly anybody knew it. Ghosh was his family name, but Bhonda meant in Bangla unsmart, unintelligent man. Whether he deserved this epithet, I could not know. But his only item of snack, “Beguni”* was famous in the village. Many grown-up Kamrabadi men gathered there for a chat and to enjoy Bhonda Ghosh’s Beguni. The especially articulate men among them (yes, only men!), who were fond of discussions and debates indulged in their hobby there. The graduate Kamrabadi I have mentioned above was especially articulate. He appeared to know a lot, and he also spoke a lot. And if anybody doubted the solidity of what he said, he used to reply with the sentence: “I am a graduate and my father was an officer.” My father didn’t go there. Often, I used to be sent there to fetch some Begunis for the family.

There was a small family-owned grocery shop in the village. But the range of goods offered there was small. For most necessary goods, fish and fresh vegetables, and services, like e.g., haircutting saloon and tailoring shop, we had to go to the market, which was situated in Sonarpur, already then a small town. A badly asphalted road, on which a sort of a share taxi or small bus plied, connected the town with Rajpur, its twin small town. I had my first experience of a ride on a motor vehicle on this road and with this share taxi. It was probably the only motor vehicle in this region, and it was in a very bad shape. I heard from an acquaintance that once, when he was travelling with this vehicle, suddenly it sagged on one side and stopped moving. He could see that one of the wheels, which had separated itself from the vehicle, continued to role on forward.

Sonarpur was (is) also the railway station for Kamrabad. We could reach the station in 10 minutes by walk. There we learnt a special kind of walk: walking on the wooden sleepers of the railway track, which were placed at uneven distances from each other. This kind of walk was necessary, because the railway track was the shortest way from Kamrabad to the railway station. One could of course take a proper pathway to the station, but that was much longer, and moreover muddy in the rainy season. I never saw this pathway.

In the towns in which we had lived till then, most people used their feet for going from A to B. We too. But later, maybe it was in Jhansi, father bought bicycles for my elder siblings. When we came to Kamrabad, they were hardly used, because it was a small village, and every place we needed to reach, was within a short radius. But there was one exception. My eldest sister, then 14 years old, needed to go to a girls’ school in Rajpur, because it had higher classes, which the Kamrabad school did not have. For her ride to her school, she used her bicycle. My parents may not have had any thoughts about it. But, I remember, it was a subject of talk in the village. A teenage girl wearing skirts and riding a bike. The only other time I saw someone riding a bicycle there, it was a grown-up man, very corpulent. And I thought, the thin tires would burst, but they did not.

Another thing was striking for me there. In the towns where we had lived before, horse carriages were the means of transport for people of importance and people with money. I had seen some of them. In Bengal, however, I never saw one. Not in Kamrabad, not even in South Calcutta, when we were going there to school. I saw there buses and trams, but no horse carriages. I heard of bullock carts in Kamrabad, but never saw one until many years later. The first time I had a bullock cart ride, was when I travelled to a rural area in North Bengal to bring father’s old widowed aunt to her daughter’s house. The latter was the wife of a wealthy landowner. This son-in-law, who lived in a village, quite far away from the railway station, sent a bullock cart to pick up his old mother in-law. It was rainy season. The unmetalled roads for such travel were just muddy tracks full of potholes between rice fields. It was a difficult ride, an experience.

The most pleasant and enjoyable spot in Kamrabad was the Jhil, the largest of all ponds in the village. Its water was not foul, because there was no tree on its banks, from which leaves would fall in it and rot. It was popular among the villagers of all age groups – for taking bath and for swimming for enjoyment. On one side of the Jhil, almost hugging it so to speak, ran the railway track. On the other side – between the Jhil and the next pond was an open level space, just large enough for children and teenagers to play “football” on it. I use here inverted commas, for the ball we played with our feet was not at all of the usual size. It was actually a used and discarded tennis ball. That was all the village youth could afford to buy. A real football, the usual size, was too dear for them.

After each game of such football, particularly in the football season – the summer and the rainy season – the players used to sweat. After the game it was such a pleasure to take a dip in the Jhil and wash away the sweat. Some of my playmates straight away jumped into the waters, some took off their shorts and jumped naked into it. In the late afternoon many elderly people came there just to enjoy the fresh breeze. For their benefit, the owner of the big house that stood close to the Jhil, had built a cement-paved platform (ca.5m x 4m) and two cement-built longish benches.

One peculiarity of the Jhil was its shape. Unlike all the other ponds of South Bengal, it was not roughly round-shaped. From a child’s perspective, it was exceptionally long and comparatively short in width. It was the ambition of many children to be able to swim the whole length. I did that once, and was very proud of my achievement. I later fathomed the reason for its longish shape. The Jhil was dug to get earth for raising the ground level of the railway track. This explained for me the formation of all the ponds on the two banks of the railway track.

Education

Before coming to Kamrabad, my elder siblings had gone to school, where Hindi, naturally, was the medium of instruction. I did not go to school in those towns. I was a child, not yet a boy, and kindergartens were an unknown entity in those days. I stayed at home and played with our neighbors’ children, all the while speaking Hindi. But I learnt my ABC at home. I was fortunate to have a private teacher, a young man, who had come to Jhansi in order to search for a job, and was staying in our house as guest. Father was to help him get a job. He gave me the first lessons in English and arithmetic. I cannot say how old I was then, maybe somewhere between 6 and 7.

I do not know how I learned to read Bangla. But I remember that my father, when he went to Calcutta for some office work, brought for us Bangla children’s books. And I could read the story books presented to me. I read it them loudly to show the others that I could read Bangla.