Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Gill Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

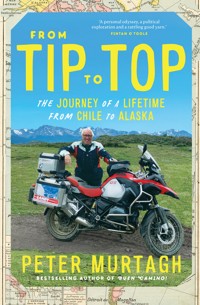

Peter Murtagh decided it was time to embark on 'The Great Retirement Project' - riding a motorbike from Tierra Del Fuego at the very southern tip of South America, to the most northerly point in Alaska, alone and without the pressure of any deadline. Aged 69, just him, a tent, a bike and a sleeping bag. En route, Peter explored magical, wonderful and extraordinarily out-of-the-way parts of our bruised world, met incredible people from all walks of life and observed a great swathe of the Americas. Travelling alone on the 45,000km journey allowed him a rare opportunity to disconnect from hectic daily life and to embrace the solitude, challenge and peace-of-mind of the road less travelled. From Tip to Top is a story of optimism and hope and the adventure of a lifetime, and is a ground-level portrait of the Americas as we rarely see them.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 546

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

For Ian Broad1944–2021

And also in memory of Patricio Corcoran1954–2023

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Map

Dedication

Introduction

SOUTH AMERICA

Chile and Argentina

Bolivia

Peru

Ecuador

Colombia

CENTRAL AMERICA

Panama

Costa Rica and Nicaragua

Honduras and El Salvador

Guatemala

NORTH AMERICA

Mexico

Texas and Arizona

California

Oregon and Washington

British Columbia and Alberta

Yukon

Alaska

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Copyright

About the Author

About Gill Books

Praise for the Author’s Works

Photo Section

INTRODUCTION

IN 2019, after nearly forty years working full time as a journalist, I retired from formal employment and faced all the anxieties that confront many retirees. Do I have a reason to get out of bed on Monday morning? What do I do with the rest of my life?

I had been a reporter and an editor, spending most of my career at the Irish Times and the Sunday Tribune (also in Ireland) and about a decade in the United Kingdom, working in London, briefly for the Sunday Times but mostly, for eight years, for the Guardian. I’m also a husband and a father and have lots of interests outside journalism. But still, for most of my life up to that point, the question ‘What do you do?’ – and the answer to it – was what defined me, to myself as well as to others. So now, entering retirement, what would the answer be? ‘Well, nothing, actually. I’m retired’? The prospect induced a mild degree of terror in me. I wasn’t ready to give up journalism. I didn’t want to stop doing what had been my passion for all my adult life: reporting, getting out and about, meeting people, finding things out and telling others all about them.

The end of my formal career came on 11 April 2019, shortly after 5 p.m. in the Irish Times newsroom in Dublin, two days after I had turned sixty-six. I chose to work the extra year after sixty-five and also right up to my last day, eschewing the option of winding down by working one day a week less each month over several months, to the point where I would hardly be doing even one day a week. The idea of the wind down was that the cut-off moment, when it came, would seem less abrupt. Or so the reasoning went. No, I thought, I’ll just carry on as normal right up to the end, and when it comes, well, that’s it; it’s over. I’ll walk out the door and simply won’t be working the next day.

Before I retired I attended a short course that included a lot of genuinely useful practical advice about pensions and other entitlements. There was also a pep talk about exercising. ‘Practise picking yourself up off the floor,’ said a Pilates lady. ‘You’ll find it easy enough now, but the day will come when you’ll fall over and find it very hard to get back up without help. So practise now …’

I remember wondering gloomily, ‘Is this the future? Am I but an enfeebled stagger away from sitting in a winged armchair in the corner of a crowded old people’s home, being spoon-fed puréed food by a care assistant?’ I was, and remain, determined to be as active as I can, for as long as I can.

Within a few days of my final shift, I headed to south-west France to walk 350km of the Camino de Santiago, crossing the Pyrenees into Spain and going as far as the small town of Frómista, west of Burgos. I try to walk the Camino, or a good chunk of it, every year because of the great pleasure it gives me, a lapsed Protestant-cum-atheist, and because it’s also a terrific way to keep fit. My wife and I then flew to America for the wedding of the son of some good friends. We tacked on a holiday during which I did some hillwalking in New Hampshire, and we roamed around Maine, enjoying the coastal beauty of that state. In July, with some friends, I went climbing in Switzerland, scaling three mountains in a week, each about 4,000m high, in support of a cancer research fund, the Caroline Foundation. But even with all this frenetic activity, at the back of my mind was another trip I wanted to undertake. It was one that had captured my imagination for a couple of years: riding my motorbike from the bottom of South America right up through the Americas to the very top of Alaska, to Prudhoe Bay and a place named Deadhorse, where the road ends and you can go no further. Far from being the first to undertake this journey, I would nonetheless be joining a select band of adventure bikers to have done it.

I was not a seasoned adventure biker, skilled in off-road riding (though I had done two brief off-road courses in Wales and Scotland), neither was I sufficiently mechanically minded to be able to fix the bike should it break down. I had gone to two demonstrations in emergency puncture repairing and bought the necessary equipment, but that was about it. However, I had been biking for over ten years and had ridden long distances around Ireland and the UK as well as several parts of Europe, including the Balkans, and also Chile and Brazil. The special feeling of freedom that comes with biking, of moving through the landscape but not being separated from it by travelling inside a metal box, is very seductive. And adventurous travel – the idea of just going, of coping with whatever happens along the way – appeals to me enormously and is a long-suppressed part of my make-up, going back to my twenties.

In 1979, while living in Denmark in my late twenties and working as a painter and decorator and as a gardener, I was asked by a woman whose garden I was doing whether I wanted to crew on a small wooden yacht owned by a man across the road who was sailing to Africa in three days’ time. I jumped at the chance even though I had not sailed before, a detail that didn’t seem to worry the boat owner or indeed me.

There were five of us: Lars, the captain; his friend Peter; Peter’s wife; their son, aged about ten; and me. Soon after we left Copenhagen harbour, we were hit by a horrendous storm, forcing us to shelter in one of Denmark’s many islands. After that we went through the Kiel Canal to Helgoland, where Lars caulked the yacht’s timbers to seal several leaks. Later we rested in Dunkirk and in Guernsey’s St Peter Port before crossing the Bay of Biscay in one go. We crewed by rota – a couple of hours on, then the same off for sleep – and my pulse still quickens remembering sailing alone at night, setting our course with the compass and then staying it by keeping the mast aligned with the stars. In our wake the sea was lit up by phosphorescence, glistening magically in the deep night blackness.

When we arrived in Vigo, north-west Spain, I left to go my own way, hitchhiking to North Africa and mostly sleeping rough. In Morocco I hated the hassle and constant pestering and, after Tetouan, got a bus east to Oujda, by the border with Algeria. The contrast between the two countries was immediate: whereas Morocco was desert burnt and poor, Algeria was irrigated and green, and the people were genuinely interested in who I was. They wanted to know what Ireland was like and took pride in telling me about themselves and their country.

I hitched to Oran (about which I remember absolutely nothing) and then south, in a great loop across the northern Sahara, taking in Laghouat and Ghardaïa, where I chickened out of going deeper into the desert, wheeling round instead to Touggourt and El Oued and on into Tunisia. There I got a lift in a Norwegian camper van heading for Genoa, where the Norwegian Seaman’s Church served waffles daily to the homeless … and to young travellers chancing their arm. That adventure ended with the best hitch I’ve ever achieved: a single lift from outside Genoa to the central train station in Copenhagen, not far from where I lived. The driver was a Yugoslav shipyard worker on his way back to Sweden.

So adventure – and coping with the things that just happen, the people one meets, the other lives and the scenery – has a magnetic attraction for me. Retirement would not be an end but a beginning, a renewal while there was still time, a determination to keep grabbing life with both hands and living it to the full. That’s why I did this journey.

This book is a compilation of my weekly reporting for the Irish Times, blogs written for my website, Tip2Top.ie, and extracts from my road trip notebooks. I hope you enjoy it and that it encourages others – especially anyone faltering at the thought of doing something similar – to steel themselves and just go for it!

Greystones, Co. Wicklow, and Louisburgh, Co. Mayo, October 2023

SOUTH AMERICA

ON 10 NOVEMBER 2022, American Airlines flight 723 took off from Dublin Airport, bound for Philadelphia and with me on board. I was anxious and excited in equal measure – anxious about the adventure I was resuming but excited also finally to be doing it. It had been aborted in late March 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic then sweeping the globe. Now that was all but over, conquered by vaccines. In Philadelphia I would catch another flight to Miami and, finally, a third to Santiago, capital city of Chile, arriving just before nine the next morning, Friday 11 November. A few days later I would fly further south, to Punta Arenas.

As the plane took off from Dublin, I thought to myself, ‘At last, at long bloody last.’ I had just one piece of luggage – my rucksack – packed with not very much: a sleeping bag and a change of clothes. Not a lot, considering I planned to be away for at least seven months. Everything else I reckoned I would need was with my motorbike, my Irish-registered BMW R1200 GS Adventure, which I hadn’t seen since April 2020. A few weeks before that date, the bike had been airfreighted to Buenos Aires via Mexico City, and that February I had followed it to the Argentine capital. From there I rode 3,000km south, across the Patagonian Desert and over the border into Chile, to Punta Arenas, the capital of Chile’s southernmost province, Magallanes y la Antártica Chilena.

In those early months of 2020, as I crossed the Pampas and was buffeted by the austral winds of Patagonia, I could sense the virus also creeping up behind me. In Buenos Aires everything seemed fairly normal: no one was wearing masks and there was little sign of hand gel, soon to be ubiquitous. But by the time I got to Río Gallegos, about 70km from the southern border with Chile, even the teenagers who hung round petrol stations, hoping to earn a few pesos helping motorists, were wearing masks and surgical gloves. At one station there were several bikers, and the word among them was that the frontier was closing at midnight. It would stay closed for at least two weeks, it was said, but that would be okay, I thought: there was enough for me to see and do for a fortnight in Chile’s far south. So while the other bikers turned back, I sped on to the border and got to Punta Arenas just as the sun set on 16 March 2020.

Taoiseach Leo Varadkar’s St Patrick’s Day address the next day on the scale of the Covid crisis hit home and prompted anxious text messages to me from my wife. Within days it was clear that South America’s borders wouldn’t be reopening any time soon. After closing its border, Chile banned foreigners from using the country’s ferries, meaning I could neither go further south within Chile, to Puerto Williams, nor turn north, using the Pacific Ocean to bypass the Southern Patagonian Ice Field and get into the rest of the enormously long country.

I was trapped in the far south, and even though life still seemed normal – people walked the streets or went to the supermarket, even if shops spot-checked shoppers’ temperature – TV news reports told a different, and increasingly alarming, story. The dying had started and had reached Punta Arenas, including the house next door to my hostel. One day Eliana Valencia, the woman who ran it, was hosing down the entire exterior of the building, in the belief that she would wash away any virus that might be there. Inside, we were becoming inmates – Eliana and me, a young midwife named Anni, and Marcos, a chef from Ecuador.

The final nail in the coffin of my great adventure came soon after, on 22 March, when the Chilean government announced a nationwide curfew from 22:00 to 5:00, amid suggestions that it might be extended until June and become a twenty-four-hour curfew. During the curfew, no one would be allowed out of their accommodation save for medical emergencies or to get food. People were starting to lose their jobs as businesses, especially in hospitality, began shedding staff. It was obvious that I needed to get out of the country – if I could.

It took a few days to arrange, but I got standby on a LATAM flight from Punta Arenas to Santiago for 1 April and a seat on the last British Airways flight to London on 3 April. Eliana and Marcos drove me to the small airport in Punta Arenas, which was chaotic, as residents of other places in Chile, tourists and contract workers all tried to get home before the curfew came into force. Eventually, I got one of the last seats to Santiago, where I stayed two nights in a hostel near the airport, before getting the last BA flight to London. Both flights were crammed and I felt certain that I would catch the virus.

I got home to a virtually empty Dublin Airport, where my wife, Moira, and our children, Patrick and Natasha, threw me the keys to a second car so I could escape to our holiday home in Co. Mayo to isolate. On the way there, a garda stopped me near Croagh Patrick and asked where I was going.

‘To Louisburgh,’ I said.

‘And where are you coming from?’

‘Chile.’

He looked at me blankly, paused, and then, apparently deciding not to probe further, said, ‘Grand, so. Carry on.’

Miraculously, I didn’t catch the virus during my escape, but during the pandemic, 5.3 million Chileans would, with more than 62,000 of them dying.

Back home and safe, I was relaxed: my bike was secure, locked in a Punta Arenas warehouse owned by my new friend there, the Chilean Irish rancher, supermarket owner and local Kerrygold agent Patricio Corcoran.

I thought I’d be back in Chile after a few months at most, when all the fuss had died down, resuming my adventure. The naivety of it! It would be over two and a half years before I could return.

CHILE AND ARGENTINA

12–17 NOVEMBER 2022, PUNTA ARENAS, CHILE

The flight from Santiago began its slow but steady descent, wheeling left across the Strait of Magellan, the windows on the right side tilting upwards to give me a glimpse of the snow-capped Andes.

The Andes! Again, and at last, so close I could almost touch them – the same feeling I had two and a half years previously when mask-wearing soldiers stopped me just outside Puerto Natales to say, politely, no, I could not go further. ‘Covid,’ they said, as if I needed telling.

Now, with the curse lifted for almost everyone everywhere, I was back, a bundle of excitement and anxiety. Excitement because this was the resumption (resuscitation?) of the ‘great retirement project’, riding a motorbike from Tierra del Fuego to Alaska, alone and without the pressure of any deadline to get to place X by such and such a time or date. This would be no race, no ‘lads together having a blast’ expedition. I wanted this to be a journey of encounter and exploration, a journey partly along the famed Pan-American Highway – or the Panamericana, as it is known in much of Latin America – but one with the freedom to go this way or that as the mood or the moment took me.

But there was also more anxiety this time. Maybe it was post-Covid angst; maybe it was appreciating better than the previous time the anxiety I was causing in others – in my wife and children and among my wider family and friends – by doing this. But my selfish self was still doing it. Maybe it was the gnawing realisation that, nearly three years on, I was in my seventieth year and no longer had the strength or fitness I had as recently as 2020. I had by then developed a touch of arthritis in the joints where my thumbs join my wrist. Sometimes I can’t twist the lid off a jar. My doctor has me on statins (a low dose, but heart pills nonetheless) and also something for blood pressure, and when I told him about the trip, he commented, ‘Ballsy,’ half admiring (I suspect), half thinking (I also suspect) that there’s no fool like an old fool.

So what made me think I would be able to upright a toppled BMW R1200 GS Adventure, a vast machine by any measure – weighing over 250kg, luggage excluded – when, inevitably, somewhere along the way to Deadhorse, Alaska, it would indeed topple over? I didn’t know, but I’d find out!

The Magellan Strait waters looked unusually calm from a few thousand feet up, but the bent-over trees around the airport reminded me that this is a place of extreme winds, the great south wind that blows, and blows and blows, seemingly without end. It was late spring in the Southern Hemisphere, but the ground below was visibly burnt and bone dry, showing little evidence of winter growth for grazing sheep.

When I came through the airport, there was no sign of Eliana, who said she might be there to meet me and bring me into town. Eliana runs the El Patagónico Hostel, on the way into Punta Arenas. I stayed there last time for no reason other than that hers was the first bed-for-the-night sign I saw. I thought then that I’d be there for two weeks, the initial period for which the border was due to be closed. In the almost three years since then, Eliana and I had kept in touch via Facebook Messenger. She’s a hoot is Eliana – friendly and kind, funny and playful. Her hostel is an Aladdin’s cave of stuff – stuff everywhere that hasn’t been opened or used for yonks, broken-down stuff and other things that will probably never be used. It’s like living in the centre aisle of Lidl.

I jumped into an airport taxi, and on my arrival the hostel door burst open. Eliana threw out her arms to give me a great big hug, laughing a laugh that said, ‘Well, isn’t this just gas?’

‘Peeeeeeter! Cómo estás, amigo?’

‘Grand, just grand. Great to be back!’

Inside, everything was much the same as before, except that the massive TV – it must be at least sixty inches across – that in March 2020 was blaring out the end of the world from its wall mounting now lay flat across the breakfast table, smothering it almost entirely. ‘Muerta?’ I asked. ‘Sí, muerta,’ she said. Never mind, I thought, feeling sure that it would be kept nonetheless … finding a home with the two dead cars out back and the other bits of debris, a bicycle, some class of Husqvarna compressor and lengths of timber and plastic. Later, out there, Eliana showed me a small corner that had been cleared and wooden pallets that had been laid down to give an even, solid surface while leaving enough space for two plant beds along a rear and side wall.

‘Tomates?’ I asked.

‘Sí, maybe,’ she said.

On the way to my bedroom, at the turn in the creaking stairway, there was a three-foot pound-shop Santa Claus, smiling and wishing me a feliz Navidad … and I got the eerie feeling that he had been there too when I stayed here first in March 2020.

After I unpacked my rucksack and caught my breath, I went back downstairs. Eliana had news for me: beaming, she told me that she had a new man. Two and a half years before, she was still in mourning for her then recently deceased husband – ‘my best friend’ she would say, eyes welling up. She said she thought of him every day but would try to lose herself in her hobbies: painting, photography and birdwatching.

‘Alex!’ she announced to me, simultaneously summoning the new man for presentation. He was a little stocky (Eliana herself is small in stature) but broad-shouldered and muscular. He had a big smile and shook my hand warmly. He told me that Eliana had spoken a lot about me. I asked whether they were married, pointing to my wedding ring to supplement my appalling Spanish. But, no, they were just together, they said. ‘Living in sin,’ I pronounce, and they both laughed uproariously.

‘Es un hombre muy excelente,’ Eliana said proudly of Alex, adding that he was her ‘compañero de viaje’, her travelling companion, and that this was how they had got to know each other.

I went for a stroll to a nearby supermarket to acquire vital supplies, such as wine. It was strange to see spring flowers in suburban gardens – dandelions, millions of them everywhere, but also peonies, laburnum and yellow broom, sometimes fashioned into bright hedging. When I returned with the wine, Eliana invited me to join her and Alex’s late-afternoon Sunday lunch of empanadas and pickles. The wine went down well, and I went to bed wondering what tomorrow would bring.

*

When in late March 2020 the Chilean government announced a curfew, it was clear that my plans were scuppered. I had just interviewed a local Chilean Irishman, Patricio Corcoran, who ran a food distribution company and three mid-sized supermarkets. I suspected that he had warehouses, or at least access to one, and might be able to store my bike for a couple of months, as I then expected I would need.

Patricio was quietly proud of his Irish heritage. In his office he kept two old British passports belonging to his grandfather and father, both of which show Irish birthplaces. His grandfather, Charles Peter Corcoran, was born in Co. Cavan but lived in Dublin. Patricio’s father, Arthur Bartholomew Corcoran, was born in the city in August 1919 – a difficult time in Ireland, politically and economically. So when the Chilean sheep-farming company La Sociedad Explotadora de Tierra del Fuego recruited among the Irish and Scots for pioneers who would emigrate to Patagonia, Charles Corcoran signed up, taking with him his one-year-old son, Arthur.

When I met him, Arthur’s son Patricio was the embodiment of the successful immigrant. He and Sylvia, his wife of forty-three years (she’s a Blackwood, with lineage going back to Scotland), had three children and ten grandchildren. Apart from the food business, Patricio also owned a farm near Punta Arenas, which had some 2,500 sheep (the local average was closer to 5,000) and 500 Angus beef cows. The calves were matured on another farm near Puerto Montt, north of the Patagonian Ice Field, from where they were sold for slaughter.

Patricio was something of a local contact for the Irish embassy in Santiago, which put me in touch with him. My plea for his help in March 2020 was answered with an immediate and generous yes, and so I left my wonderful, almost-new bike on 31 March in a Corcoran Express warehouse, under a cover and with various bits and pieces stuffed into two bags and hoisted on a pallet up onto the top shelf of the huge building.

Now, two and a half years later, I really didn’t know what to expect. The bike’s battery would surely be dead, but could it be revived? And the tyres, had they deflated, and had the rubber cracked and perished? The petrol and oil would have to be drained. I’d have to get the whole bike serviced, surely.

I emailed him. ‘Patricio! Am finally in Punta Arenas. Would it suit if I called around at 11 tomorrow morning?’

‘Peter’, came the reply, ‘your bike is ready. We have to pick it up in a garage I sent them. 11.00 am would be great …’

Down one of the roads near my hostel, Alejandro Lago runs a workshop where he services machines used by an adventure-biking company specialising in motorcycle tours of Patagonia. Patricio drove me there, and it was obvious from the workshop – from the equipment, the bikes being worked on, the big Dakar sign over his workbench and all the stickers left by visiting long-haul adventure bikers – that Alejandro knows his stuff and is a mechanic well trusted by bikers.

Mine was there – gleaming clean, fully serviced at Patricio’s request. When I pressed the starter button it snapped into life with that deep-throated, satisfying GS purr. The years of enforced inactivity were blown away in an instant, and with them all my worries. A spin north, out across the Patagonian Desert by the airport and on towards the Argentine frontier, proved that everything was running perfectly. Everything I left behind in Patricio’s care was retrieved: all the biking gear, the camping gear (an MSR Hubba Hubba NX tent – the most expensive item I took with me, after the bike and my laptop and phone – and as yet unused) and all the related equipment.

That night Patricio invited me to dinner in Sotito’s, one of the best restaurants in Punta Arenas. Over locally caught king crab, octopus, abalone, grilled fish, pisco and wine, we talked Chile, Ireland, England, politics, family and climate change. The absence of new-season grass I had noticed from the plane was due to a lack of rain, he said. The relative lack of water meant that he was now drilling to get some, with pumps using solar power. From the actions of the restaurant owner and staff, it was clear that Patricio was well known and well liked. As we exited, he paused at one or two other tables to chat briefly with friends who were also dining.

I walked on slowly so as not to intrude. The waiter sidled over to me and smiled, gesturing towards Patricio. ‘Rock star,’ he said.

I could not but agree.

22 NOVEMBER 2022, PUERTO WILLIAMS, ISLA NAVARINO, CHILE

The main ferry port out of Punta Arenas was just down the road from Eliana’s hostel, and that’s where I headed in my quest to get as far south as I could before turning round and heading north. Ferry rides are generally perfunctory affairs. You get on board and do what you have to do to get through the tedium of the journey – play cards, fill in crosswords, read a book, whatever – except when you’re on the Austral Broom’s ferry Yaghan from Punta Arenas to Puerto Williams, the place farthest south in Chile that it’s practicable to go, south of Argentina’s Ushuaia, the better known ‘most southern town in the world’, which it really isn’t. On this overnight journey, you don’t need distractions because there’s just far too much to see: epic seascapes churned up by the southern winds, seabirds performing aerobatics over the waves, raw and edgy landscapes and place names straight out of childhood adventure stories and geography class.

We set sail down the Strait of Magellan at about six in the evening, passing Cape Froward and its lighthouse, the final tip of the continental landmass of South America. In 2020 I had ridden there, and I did so again a few days before sailing, revisiting the grave of the luckless Pringle Stokes, captain of the first Beagle voyage, whose depression caused him to take his own life in August 1828. His grave overlooks the strait near Port Famine (Puerto del Hambre), about 50km south of Punta Arenas and near where the most southerly road on continental America ends a little further on, at Cape San Isidro.

As the ferry sailed past, in the far distance and in the fading gunmetal light of the night sky, I could just about make out the snow-capped mountains of the islands that make up the network of land and sea channels that comprise the toe-shaped formation of Tierra del Fuego and Cape Horn. It’s an exhilarating sight. Not for no reason did the travel writer Bruce Chatwin describe the strait as a case of nature imitating art.

The Yaghan is a workhorse, a giant version of the sort of landing craft used on D-Day, with a bow door that opens down, creating a slipway for vehicles to gallop ashore. It’s primarily a cargo vessel that also caters for passengers, and its deck was crammed with containers, vans and four-wheel drives, oil drums, wooden pallets, a dozen ton-bags of cement, lengths of steel and mesh for fencing. And now also my bike.

During the night, the ship threaded its way south like a darning needle, passing between islands and through channels whose names tell the story of the discovery of this place from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries. We avoided fully entering the Pacific, passing instead on the inside of Isla London and into the Ballenero Channel, north of the islands of Stewart, Gilbert and Londonderry. The channel is squeezed narrow as it passes between Londonderry to the south and O’Brien Island to the north, before passing Darwin Island and entering the Darwin Channel.

North of us is Tierra del Fuego and the dark, brooding mountain range of the Cordillera Darwin – a set of snow-capped peaks and glacier tongues flowing off them but not quite dipping into the sea. They once did, before global warming began to eat away at them, as is evident from photographs taken a mere decade ago.

The ferry moved slowly, providing passengers – some locals and also some tourists, from France, Italy, the Far East and the United States – with ample time to take in the sights. The island scenery is astounding. Gigantic in scale and inhospitable in nature, the weather-beaten land masses are a shade of deep grey just short of black, their peaks white and their flanks broken by blotches of snow above the treeline. Despite some vegetation and forestry, there’s no visible evidence of habitation. Seabirds abound and the star performer by a long shot is the petrel. Often flying solo, the bird moves upwards in graceful arcs, falling again to the water to glide at great speed and with seeming effortlessness, its wingtips almost brushing the tops of the waves.

We entered the Beagle Channel, which separates Chile and Argentina, and docked briefly at Yendegaia on Chilean Tierra del Fuego. Tierra del Fuego is an island that is split between Chile and Argentina; the Argentine town of Ushuaia, southernmost destination of most adventure bikers in the region, is a little further east of our landing place. At Yendegaia there’s a small slipway but nothing by way of a settlement, save for a small Chilean Army presence and a rough road north, connecting ultimately with Porvenir, a Chilean town on the opposite side of the Strait of Magellan to Punta Arenas.

I walked about a bit while some building materials were offloaded, but I wanted to go further south still and stay with the ferry as it resumed its journey. A little further on through the channel, we docked at Puerto Williams about midnight. Foot passengers alighted, but all remaining cargo stayed put, my bike included. ‘Mañana,’ said a crew member, adding that I shouldn’t worry: I could sleep on the ferry. In the meantime we returned into the channel and dropped anchor, and I went to sleep for the night in a reclining chair.

Next day and back at the slipway, I disembarked and parked the bike immediately outside the Refugio El Padrino, a brightly coloured wood-and-tin hostel beside the harbour. But I had to move it almost at once. I was, apparently, taking up Cecelia’s place. She was another larger-than-life hospitalera, who greeted me like a diva, proffering both cheeks for a kiss and administering a warm hug at the same time. ‘Come in, come in,’ she insisted, telling me that I was to have eggs and cheese and bread and coffee before we discussed matters. ‘Sit!’ she commanded, and who was I to question her?

The hostel kitchen–living room was typical: an amiable clutter of posters, maps, photographs and flags. There was a beaver pelt nailed flat onto the wall. The place was named in honour of Eduardo Mancilla Vera, an otter and sealion hunter who came to Puerto Williams in the 1940s and stayed until his death, aged eighty-one, in 2003. He spent his life helping create the town and championing its cause, lobbying the authorities for facilities and investment. He was so respected by the inhabitants that many of them named him as godfather to their children – hence his nickname, El Padrino (‘the Godfather’). Eduardo was Cecelia’s dad.

Puerto Williams has a real pioneer town feel to it: gritty, dusty and unkempt. Some roads are concrete but most are just compacted earth and gravel. They kick up dust when a vehicle passes. The original houses, those closest to the harbour, have a run-down, paint-peeling, shanty-town appearance. They’re jumbles of plywood and sheet metal, often with satellite dishes nailed onto their fronts. Gardens, as generally understood, are virtually non-existent. The areas in front and around the sides of the houses are car parks and places for piles of timber, chopping blocks and other stuff. There are dogs everywhere. Many other homes further back from the harbour are owned by the Chilean Navy and are better kept. The best buildings in the town are invariably associated with government. Puerto Williams as a town didn’t come into being formally until November 1953 (the year of my birth), and there was to be an anniversary marked in the town the next day.

For now, however, I attempted my trek across the island to Lake Windhond, which is about 25km directly south from Puerto Williams and where there’s a shack, the Refugio Charles, the most southerly place I could sleep before turning north and heading for Alaska, some 40,000km away. This was the bottom-most tip in this Tip2Top adventure.

The hike started at a small settlement named Villa Ukika, where the Ukika River enters the sea about 2km east of Puerto Williams. Villa Ukika is populated almost entirely by the surviving members of the Yahgan people, the Indigenous people who were ‘transferred’ there by the Chilean military in the 1960s. It’s where they continue to live today in about a dozen wooden houses. I was curious about the Yahgan and the Ona, or Selk’nam, people of Tierra del Fuego, who had all but ceased to exist in any meaningful way outside of images on tourist tat. Recent scholarship has found evidence that the Sociedad Explotadora de Tierra del Fuego funded the murder of Selk’nam in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, paying £1 for every person shot dead, the evidence for payment being the presentation of a severed hand or ear.

I walked to Villa Ukika from Puerto Williams and set off down the Ukika River valley through dense woods, on a trail indicated initially by two parallel red lines on a white background painted onto tree trunks. There was no road, just this trail. My compass bearing showed exactly 190 degrees, pointing precisely south. But after perhaps four kilometres, the trail marker signs disappeared, and soon I became hopelessly lost. For the moment, I was able to confirm my direction not just by my map and compass but also by following the skyline of the mountain ridges on the side of the valley. But what should have been a simple enough trek with these aids became more and more difficult as the woods thickened and fallen trunks and debris slowed progress to a painful crawl – sometimes literally. An ant would make faster progress through a ball of wire wool. I become increasingly concerned that if anything untoward happened – a fall, a sprain or, worse, a break – no one would know where to find me. The trail itself had disappeared, so how could they?

Forward movement became more and more arduous and, having zigzagged up and down the side of the valley, trying to relocate the trail, I descended to the valley floor. If nature does dystopia, this is maybe close to it. While it looks beautiful, the area is strewn with timber wreckage created by beavers chomping away at everything in their path. The creatures were introduced into Tierra del Fuego from Canada in the 1940s in the hope of creating an Argentine beaver fur industry, but it didn’t work out. Some of the animals escaped, swam the Beagle Channel and populated Isla Navarino. Now the entire Ukika Valley floor is a maze of dams, lakes and swamp, of gnawed-off stumps and timber debris. Any trees left standing are dead, and the whole landscape looks not unlike bomb-blasted no man’s land at the end of the First World War.

By 4 p.m., after some five hours’ hiking, I had covered only about 12km – half the distance to the lake. I decided to give up and pitch my tent where I was, on a dry mound sandwiched between the forest and the swamp. I will sleep with the beavers, I thought to myself. At night, however, all I heard was the sound of bats and of wild dogs barking, four or five of them further up the valley – where no one lives …

I awoke to find a lone goose, a Magellanic bustard, a grey-headed fellow with a lovely rust-coloured chest, standing by the beaver lake, just feet away. We sized each other up for a few moments before it waddled off, unfazed by my presence. I decided not to risk further trekking alone and, knowing the river would reach the sea, started to follow it back downstream. Wild horses had done the same and conveniently flattened out a path – not to Lake Windhond, unfortunately, but back to Villa Ukika.

Next day, back in Puerto Williams, they were getting ready in Plaza Bernardo O’Higgins to mark the town’s sixty-ninth birthday. The school band, the Banda de Guerra, led the parade, followed by a marching column of about sixty naval ratings and a dozen or so officers, who were formally inspected by the regional governor, George Flies, and the commander of the navy’s Beagle Channel operation, Comandante Cristián Yáñez. Flags of the town, the region and the country were raised and the national anthem was sung. The governor and the mayor, Patricio Fernández, made the sort of speeches governors and mayors make on such occasions, praising the people and their town for all they have accomplished and for the bright future that awaits them. Medals were presented to naval servicemen and servicewomen and local worthies; kindergarten and school children paraded.

Wearing a Sandeman port–style, broad-brimmed black hat, poncho and black leather boots with spurs, the traditional Chilean dancer Pablo Suaso led his troupe through several foot-stomping, skirt-and-handkerchief swirling numbers by the bust of Bernardo O’Higgins, Chile’s liberator from Spanish rule. ‘My hero,’ said Pablo when I chatted to him. Bernardo O’Higgins was the illegitimate son of Ambrose (later Ambrosio) O’Higgins, late of Co. Sligo and Co. Meath, forced off his lands by Oliver Cromwell. Ambrose would become a servant of the Spanish crown, a merchant prince made viceroy of Peru, governor of Chile and marquis of Osorno.

Before leaving Isla Navarino the following day, I decided that, since I couldn’t hike south, I should ride the road west as far as the island lets me. The way out of Puerto Williams is a dusty, gritty trail that wends its way hugging the south coast of the Beagle Channel. Up, down and over hillocks, on and on it goes for over 50km. Biking on dirt roads involves real concentration: front and rear wheels take on a life of their own when hitting a patch of loose gravel. But take it handy, stay under forty and you’re okay. Besides, on this road, there’s far too much to see, far too much beauty, to be rushing.

On that early summer’s day, the water in the Beagle Channel was still and glistening in the sunlight. The sea is a mirror to all the world above it. The mountains of Argentine Tierra del Fuego on the far side were jet black and snow-capped; the sky was filled with big frothy clouds but sufficiently broken for there to be large patches of blue too. In the water of the channel, the world was displayed twice over.

On my side, the vegetation was surprisingly lush coming from ground so apparently dry and poor. There were banks of Chilean firetrees, with their bright orange-red flower. A group of condors circled above – wheeling in huge arcs, their wings outstretched and unmoving but held aloft on the wind, gliding effortlessly, as though by magic. As I biked along, I passed numerous apparently abandoned farmhouses – timber-and-tin shacks, for the most part, and pretty; but they’re hard places in which to live, I suspect, in the winter. There’s no question of electricity out here: gas if you haul the cylinders from Puerto Williams, logs otherwise.

Around a corner I came to a sign, Cementerio Indígena de Bahía Mejillones. In the graveyard, large plots were enclosed by low picket fencing, but there were no individual markers or names, save for one plot in which a weathered board announces that the plot was for the Familia Torres, with occupants dating from 1931 to 1946 and one later interred but with the date indistinct.

At the back of the graveyard there was a single grave, a new arrival in a plot delineated by fresh timber edging and newly planted flowers, some plastic. Behind the grave was a tiny glass-fronted shrine with a small pitched roof. Inside were more flowers, a statue of the Virgin and a framed photograph: a picture of a woman glancing sideways and showing a wonderful face, weathered and lined but alert and with glistening eyes.

A cross states that she was Cristina Calderón Harban and gives her dates as 24 May 1928 to 16 February 2022. She lies in one of the most beautiful places I have seen. I didn’t know it when I stumbled upon her grave, but Cristina Harban was the last full-blooded Yahgan, known to all as Abuela Cristina (‘Grandmother Cristina’). She was a basket-weaver, ethnographer and cultural activist who lived in Villa Ukika and had ten children and nineteen grandchildren. One of her daughters, Lidia González, was elected to the Chilean Constitutional Convention and served as deputy vice-president.

The convention was designed to write a new constitution for Chile, replacing the 1980 one that was devised by the Pinochet regime and amended no fewer than fifty-two times since. The new body had 154 elected members, and it was heavily politicised, unlike Ireland’s Citizens’ Assembly, on which it was partly modelled and which comprises ninety-nine randomly selected citizens and the chairperson. In September 2022 the Chilean electorate, by a convincing margin of 62 per cent to 38, rejected the new convention-drafted constitution. One of the main reasons (among many) was a sense that, by saying Chile should be a ‘plurinational’ state, thereby recognising the rights of its 13 per cent Indigenous people, a nightmare of disputes over land and resources could be opened up.

At the celebrations in Puerto Williams marking the town’s sixty-ninth birthday, I noticed that the regional governor, George Flies, gave a particularly warm embrace to an elderly woman, a member of the Indigenous community, leaning down to hug her warmly – a gesture she reciprocated with equal warmth.

On the overnight ferry back to Punta Arenas on the Yaghan ferry once again, the walls of the cafe area were lined with sepia photographs of Yahgan people: naked and semi-naked people living in the wild, their bodies painted, and carrying simple tools and weapons. A photo portrait had been added recently – that of Cristina Harban. A tribute to the last native speaker of the Yahgan people, says the inscription under a shot of her looking sideways over her spectacles, out on a world of which she is no longer part.

26 NOVEMBER 2022, EL CALAFATE, ARGENTINA

The ferry from Puerto Williams didn’t stop again at Tierra del Fuego, which was a pity. Had it, I’d have been able to offload my bike at Yendegaia and ride it back to Punta Arenas, via Porvenir. Instead, I had to stay on board, all the way back to Punta Arenas, where we docked about midnight. But unlike at Puerto Williams, the crew would not allow passengers without accommodation in the city to sleep the night on the ferry. I settled down instead on the ferry terminal building floor … Surprisingly, alone, in full biker gear, minus the helmet, I got some sleep.

At 5:15 the sun, not yet quite over the horizon, was nonetheless brightening the sky, and it was time to start the trek north. The 250km road to Puerto Natales was empty – not even a guanaco in sight – and the wind only slight. The guanaco, first cousin to the llama, is ubiquitous in Patagonia, especially to the east of the Andes and right across the Patagonian Desert steppe to the Atlantic. An attractive animal, with its brushed-rust brown coat and pert tail, it is, however, easily spooked as well as rather shy. This does not discourage it, however, from gathering in large numbers beside busy roads. Whenever a vehicle approaches, your average guanaco will look up and start fretting. Despite there being millions of hectares of desert scrub on each side of the highway, the guanaco will observe the approaching vehicle and, taking decisive action to get away from it, run straight onto the road in front of it!

For this reason, dead guanacos are not uncommon sights, distressing as they are for all concerned, save for the grateful birds of prey and insects, whose work ensures that soon all that is left of the late guanaco is an empty hide flapping in the wind and bones rapidly bleached white in the sun. There was no sign either of the flock of flamingos I observed at a lake last time I passed this way in March 2020.

By the time I got to Puerto Natales, breakfast was calling and the wind had whipped up. I ate at Noi Indigo Patagonia, a hip restaurant and hotel with great views over the sea. The town, one of the main set-off ports for vessels touring the many islands off Chile’s west coast and venturing as far as Antarctica, is flat, weather-beaten and rather dull-looking. It too has a frontier feel about it, but the most abiding feature was, without doubt, the wind, which was churning up the sea and battering everything in its path. The westerlies blow in from the Pacific, whipping round Cape Horn as well as over the Andes. As they reach the mountain range, moisture is released as rain and snow, so that, by the time the wind swoops down the eastern side of the range and onto the Patagonian steppe, it’s bone dry but fierce in its intensity. Throughout the spring and into the summer, the wind speed increases at times to 120km/h.

It felt like that on the road out to Torres del Paine, the Chilean national park that has become a Mecca for hikers because of its striking granite peaks (the ‘Towers’) and glaciers that feed a series of lakes and rivers, one of them the River Paine. The park is 181,400 hectares and attracts a quarter of a million visitors a year, half of them foreigners who pay a premium surcharge compared with Chilean visitors. On my visit, they included a busload of tourists for whom I was seemingly far more interesting than the Cordillera Paine mountain range rising above Lago Nordenskjöld, at which we were all, at least initially, gazing.

The Cordillera is the star of this place. I baulk when I hear someone describe a half-decent cup of coffee as ‘awesome’, but the mountains here truly are awesome in that they inspire awe in those who gaze upon them. It’s not just their Tolkienesque appearance – black, brooding and snow-capped – it’s their massive bulk, their scale and their imposing presence, as opposed to their mere size (the tallest is only 2,884m above sea level; for reference, the Matterhorn is 4,478m). The impression they make is due to the scale and the sense that, when standing even hundreds of feet away, one is in the presence of something truly massive. It was all a little overwhelming.

The lakes – Nordenskjöld, Pehoé and, nearby, the glacier-fed Grey Lake – are a striking azure. Their beauty appears somehow unreal, but there they were, one after another, right in front of me. Rivers flowing off the snow-topped mountains, or straight out of glaciers, are blue-grey. Add to that the effect of a clear blue sky, and all the waters became a pure, painted blue.

I rode on and later crossed the frontier into Argentina, heading for El Calafate, a small resort town and playground for the country’s well-heeled younger set and for backpackers. The main attraction for me was the Perito Moreno Glacier, the largest in the country and the second-largest in South America. It’s unusual in that it’s melting and accumulating ice at roughly the same pace, and so it’s classified as stable in terms of the effects of global warming. It flows out of the Southern Patagonian Ice Field, which contains an astonishing one-third of the Earth’s reserves of fresh water. The glacier is 30km long and 3km wide at its mouth, where it’s also some 70m tall.

Directly opposite the mouth, on a slope of land facing it, a series of gantry walkways and platforms allows visitors to get to within what seems like touching distance of it. The front nudges into Lago Argentino, and slowly but inexorably the ice dies. Every now and then the silence is broken by a great cracking noise, sometimes a thunder-like snapping, that sends a sharp splitting sound through the air. Sometimes it’s more a dull thud, as if a shotgun is being discharged in the distance. And with the noise, another giant shard of ice falls into the water, sometimes moving as though in slow motion, the way giant things sometimes seem to – slow and powerful, even in death. I cannot stand before such a sight except in silence, scanning the details of it, the size of the mass in front of me, and just taking in what I’m seeing.

I jumped on the first available bus back to the car park from the edge of the glacier. There you can wander down to the shore of Lago Argentino and scan the blue water all the way back across the lake to the glacier. Standing there for a while, I knew before long that this was the right place to do something that I had resolved would be part of this trip.

I had brought with me some of the ashes of the man to whom this book is dedicated. Ian Broad was my geography and geology teacher in my secondary school, the High School, Dublin. Ian had a profound influence on me, and on the things I grew to love, second perhaps only to that of my mother. He fired in me an interest in buildings and building materials and, through his imaginative, field-trip-led teaching of geomorphology and glaciation, in the natural forces that have shaped Ireland and the world. He taught me how to read landscape, which I do all the time, however inadequately, and this has been a source of pleasure my whole life. Geography and geology have enriched my time, something of which I’m conscious almost every single day and was especially so on this trip.

But Ian was so much more than a teacher, so much more than a figure in a classroom who would drill us sufficiently to get us through the Leaving Certificate and on into whatever it was we chose in life. He was an inspiring educator, an irrepressible and sometimes chaotic force of nature himself. He had us climbing up the sides of the valley in Glendalough in Co. Wicklow looking for galena and garnets or rummaging for amethyst among the rocks above Keem Bay on Achill Island. He took us potholing in Co. Fermanagh and Co. Clare, where we would break open rocks looking for fossils, and to Connemara beaches to examine coral. He brought the streets of Dublin alive by showing us the visual effect of different natural materials used in walls – coloured bricks, limestone, chert and granite – and the quietly pleasing effect when marble, granite and oolitic limestone or Portland stone are combined with Victorian red brick. The multiple rock types inside the Museum Building at Trinity College were to me like an Aladdin’s cave of treasures. To this day, I marvel at the skill and artistry of the O’Shea brothers, John and James, and their nephew Edward Whelan in their extraordinary rose carvings that encircle that whole building.

Ian taught us about town planning, about the evolution of architectural style from medieval to Georgian to Victorian and how to look at details in a wider picture. He revealed to us that a streetscape – the building facades and roofs, doors and windows, seating, lamp standards, railings, granite flagstones and kerbs and coalhole covers – comprises a unified whole and that if a part is damaged or removed the whole ensemble is diminished, if not ruined. Ian fought many battles to try to save Dublin’s heritage, taking part in 1970 in the Hume Street Occupation, an unsuccessful struggle to prevent the demolition of Georgian houses on the corner of Hume Street and St Stephen’s Green. For a time he ran the Dublin Arts Festival, on which I also worked, with others, including the publisher Michael O’Brien and the future presidential advisor Bride Rosney. All of these interests, these passions, helped form much of my own outlook – and that of others, I have no doubt. The rage I feel at the destruction of heritage in Dublin goes right back to Ian inculcating in me an appreciation of all that surrounded me as a boy. That several of Ian’s pupils became geography teachers speaks to the impact he had on others as well.

Ian was gay and was never entirely at ease, if that is the appropriate term, with his sexuality. None of that was known to us when he was our teacher; but I learnt later that it tortured him and that he lived in terror of being forced to quit his job if anyone found out and took against him. That fear was the main reason he quit High School, in the early 1970s, and went to work as a teacher in China, then in Bhutan and finally in South Africa. He eventually came home to an Ireland that had changed but that still had some way to go in treating gay people without prejudice. But it was too late for him. He spoke of his sexuality sometimes with the obsessiveness of someone you knew had been damaged by the world, but at least he could now be open. He never found the love he so deserved, or at least I don’t think he did, but he did find spiritual solace with the Quakers.

Covid killed Ian. He died a horrible death in February 2021, doctors and nurses doing everything they could to get oxygen into his lungs, including puncturing his neck and chest in a desperate but ultimately futile effort to inflate them. He was seventy-six.

His sister Pamela offered me some of his ashes, and I knew immediately that I had to take him with me on this journey. I like to think that he would approve of the place of their scattering. At the Perito Moreno Glacier the Argentine authorities have worked hard to present the spectacle as an educating experience, explaining the forces that created the glacier and how it works. If some of that rubs off on visitors and helps them appreciate the natural world around them, I think Ian would approve. So I knelt down at the edge of the lake, unscrewed the lid of a small jar and tilted Ian’s ashes out and into the water. They floated gently and then sank to the bottom. They will be washed through the great lake and eventually, somewhere, will form a tiny part of the Earth. I was pleased to have done this – pleased for Ian and grateful for all that he had given me.

I rode back to El Calafate and camped for the night in a site just off the main drag. A man about my own age wandered over to my tent and introduced himself as Jaime. He looked at me, my tent and the bike as though he was about to cry. He used to ride bikes, he told me. There was mention of a Kawasaki. ‘But this,’ he said looking at mine while holding both hands to his chest, palms open, before gesturing to the machine itself. ‘This …’ He wanted to know where I was from and where I was going. I told him and he immediately hugged me, a sort of comfort hug as though I had suffered a great loss. But I realised that the loss was his. He hugged me, and implored the blessings of God upon me, because of what I was doing. And because of what he was not.

Next day I rode north out of El Calafate. The wind was ferocious, battering and buffeting me constantly. You have to lean well into it as you ride just to stay upright and, even though you get used to it, regular gusts produce scary moments. I eventually rode onto an unpaved part of Route 40, a road idolised by bikers that runs north–south for almost the length of Argentina. The gravel stretch was about 70km long and the stones were rounded; they hadn’t been steamroller-crushed into angular rocks, thereby binding them into a hardened surface. They were mostly loose and in places were many inches deep, almost like you’d find on a beach. Inevitably, I took a slow-motion tumble as the front wheel veered and the bike skewed over onto its side. Thankfully, there was no injury (to man or bike), and I discovered that I had the strength to upright the machine – which isn’t bad considering my age and its weight.

29 NOVEMBER 2022, PUERTO GUADAL, CHILE

I spent the night in a smart but inexpensive hotel in the town of Gobernador Gregores and the following one at a dingy truck-stop joint named Bajo Caracoles in Argentina’s Patagonian Desert. The mangy dogs that hung about it were better presented than the place itself. I slept on the bed fully clothed. Had I entered the shower, I reckon I would have emerged dirtier. The toilet was to be avoided entirely. I stayed there because, having thought about a particular unpaved road west – out of Argentina and back into the Chilean Andes – and having tentatively set out on it at about 4 p.m., the wind was so ferocious that I thought better of it and reversed.

I tried again next day, but after perhaps two kilometres into a stiff headwind, I admitted defeat again, turned round and resumed the (longer) tarmac route north to another border crossing. I eventually turned west off Route 40 and left Argentina at Los Antiguos.

The Chilean town on the other side, Chile Chico, is a pretty lakeside affair and noticeably more prosperous than many similar places on the Argentine side, with the exception of El Calafate. I couldn’t help wondering what role stiffing the international banks, a policy driven by populist politics, had played in Argentina’s current down-at-heel state. There was an air of decay to much of the country. Many cars still on the roads there were old, bashed and dusty. Homes looked dishevelled; people appeared poorer than they should be. Public spaces were shabby and unkempt. Chile, on the other hand, looked and felt different, more prosperous. The place had a spring in its step.