0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: BookRix

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

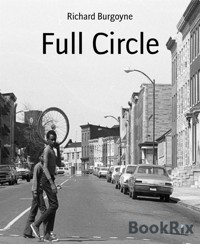

A murder, a rescue and the ultimate act of love: Full Circle chronicals the Taylor family's triumph over violence and chaos.

Rural Virginia, 1958: "For a Saturday night it was quiet, even for Slocum, a place Buddy thought no one in their right mind would choose to be."

Educated by years of domestic chaos, the Taylor children must adapt after their mother is shot by their father. Clarence, the new head of the family at twenty-two, steals a moving van and smuggles them from their rural Virginia home to a life in Baltimore, a monumental challenge for a Black family in the 1950s.

Though society conspires against them, the Taylor children are not without allies: Leo and Anna Antanucci are the owners of the moving company where Clarence Taylor works. Leo and Anna, alone and banished from their own families, have struggled to start their business and family, when a moving van filled with five children is unexpectedly unloaded on their doorstep.

Buddy, Cherise, Billy, Roy and Otis learn how to survive - and thrive - in a turbulent 1960s and 70s Baltimore, while Leo and Anna find the family they had been denied. The extended Taylor/Antanucci family makes their way through the many triumphs and tragedies thrown their way.

Cherise, the Taylor family prodigy, finds professional success in adulthood, but ultimately realizes that her life is not complete. She takes a page from Leo and Anna and works to sponsor and bring a semi-orphaned family from Iraq to Baltimore, smuggling them over the border not in a moving truck but a mini-van.

Full Circle explores issues of race and national identity, gender equality, and the ultimate triumph of love and gratitude in a hard world.

You will come to love the characters and miss them terribly when you finish the last page.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Full Circle

Thank you to Hope, my treasure at the bottom of Pandora's Box. Great thanks to my friend John who announced after reading this, "Wow, this is a real book." His comments were invaluable. Thanks too for my twin Bob who red-penned my draft into readable shape. BookRix GmbH & Co. KG81371 MunichFULL CIRCLE, by Richard Burgoyne

Those who educate children well are more to be honored than they who produce them; for these only gave them life, those the art of living well.

-- Aristotle

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.

-- Martin Luther King, Jr.

Buddy, 1958

Buddy sat alone in the amber glow of a single overhead bulb, on one of the two benches that served as the bus station for the once-a-day Greyhound that connected Slocum to the outside world. Both worn benches were pushed up against the peeling clapboard side of the general store and featured identical endorsements for sliced white bread: Merita Bread! with an enthusiastic golden-haired boy holding a peanut butter and jelly sandwich up like a prize. Buddy had seen these benches a thousand times and he frequently wondered about the happy boy wearing blue overalls, and what a sandwich like that might taste like.

There were no cars or pick-ups parked in front of the store, nor any foot traffic during the hour or longer that Buddy had been patiently waiting for anything to happen. He watched the activity above his head, as bats fed on the moths circling the bulb; there was little else to distract him. On this night he had chosen to sit on the bench with White Only stenciled above, though in truth he preferred the Colored bench because it sat higher and he could swing his feet freely as he waited and watched the rare comings and goings on Highway Thirteen.

For a Saturday night it was quiet, even for Slocum, a place Buddy thought no one in their right mind would choose to be. He briefly turned and gazed into the darkness to his left, looking south. He knew that there was little of interest that would come from that direction: the end of the world as far as he knew, a skinny arm of tired-out farm land and marsh that ended in a finger of sand tentatively poking into the Atlantic Ocean, yielding to the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. Shifting his head and body to the right he felt a subtle alteration in mood and even a flicker of hope: if a body could travel north on that two lane highway he must eventually find everything and everyone else in the deeply mysterious but promising world beyond Slocum.

Though beat up and worn thin in places, those two Merita Bread benches had represented the greater world to Buddy and his eventual escape from the Eastern Shore of Virginia for as long a he could remember. He routinely came to this sandy patch between the store and the highway, the the final stop for the Greyhound Bus, turning around in the lot behind the general store before releasing travelers from all points north. Even luckier travelers would then board for the trip back north; a ticket purchased from the store cashier could get you over the new Bay Bridge at Annapolis and on to Baltimore – and then the rest of the world.

When he could sneak away from home Buddy would walk the two miles to watch the silver and blue bus come and go at mid-day, keenly noting what the travelers wore and what they carried to and from the city. Mostly white folks, the travelers seemed to be from a different planet than the one he inhabited, always dressed up like they were going to church, and having the near miraculous capacity to depart and return to the Shore at will. Even more amazing to Buddy were the tears of sadness or joy that they elicited as they boarded or exited the idling bus. It was a spectacle the boy never tired of.

Often, on clear nights, Buddy would also walk to the store after what had passed for supper at home, restless and wanting to get away from the mess and constant noise at the falling-down shack the Taylors called home. Whether he could have explained it or not, Buddy was searching for any clues about the world beyond Slocum -- cars and trucks with passengers who might be marked in some way by their knowledge and experiences beyond the flat, sandy end-of-the-line patch that was his world.

This particular April evening was warm but too early for mosquitoes: nice out, the air yet unburdened by summer’s humidity, crickets and cicadas maintaining a steady background hum that would have yielded to a deafening silence if absent. Buddy leaned back, relaxed on the bench, his arms extended to either side, working the dry sand between his bare feet and pushing little piles up to then smooth and comb with his toes. He noted a car approaching from the south and stiffened, alert and slightly anxious as the green Plymouth slowly drove by his perch and then stopped before reversing. He did not think that sitting on the White Only bench was really against the law but it could probably lead to a beating depending on who was in that car. He did not change his posture but was now tightly coiled and ready to run if the need arose.

Buddy's muscles released their tension as the car stopped a few feet in front of him and the passenger window rolled down to reveal one of their neighbors, Mrs. Jenkins. The worst that would happen now was a scolding for being out late or sitting on the wrong bench. The heavy middle aged woman squinted at him and shook her head once the window was down.

“You one of them Taylor children, ain’t you?” Buddy could hear liquor in her voice and imagined he could smell it as well.

“Yes ma’am.”

“Lord, chile. I have some bad news for you.” She pushed backwards at the driver who was tugging at her shoulder, then leaned further out the car window and continued: “I’m sorry to be the one to tell you, but your daddy shot your momma dead, down at the roadhouse. In a car with another fella.”

Buddy’s feet were still now. He made no sound as Mrs. Jenkins resumed, as if he had asked for more details, “No sir, did not shoot the other fella, just your momma, and right in her pretty face.” She shook her head, seeming to disbelieve the details she was reporting.

“All of them drunk. Uhn huh. Other man run off and Leroy just sat down right next to your dead momma in that car, waiting on the po-lice.” She concluded in a conspiratorial tone, as if Buddy would understand, “We got outta there quick as we could. Didn’t want to get involved no more than we was,” then turned and said something sharply to the driver before concluding, “I’m so sorry baby doll. You best go and tell your people.”

As the Plymouth drove off Buddy heard sirens approaching from the north. He slowly got up and set off at a trot for home, to tell the others.

Cherise, 2017

“Still no sign of them, other passengers all gone,” I text to Anna back at our hotel room.

It has been over an hour since Air Canada 2544 from Paris had landed. All the other passengers have come and gone, though a few suitcases continued to circle forlornly on the baggage carrousel. I had started out standing with my hand-lettered “Amir” sign held high as passengers came to collect their bags, though now I am sitting, my homemade sign on the seat beside me. It is cold and drafty with the doors to the street opening and closing frequently, and I start to wonder for the first time if maybe Anna and I are in over our heads. Maybe we were hurting the Amir family? Perhaps they were now in more trouble than before we got involved. I could feel my body tightening up, ready for the What Now.

“See them yet?” Anna texts again.

Lord, I am starting to be sorry that I taught her this modern communication convenience and then got her a phone with a large enough keyboard to accommodate her arthritic fingers.

“Not yet. Sure they will be here soon,” I text back with false optimism.

Anna replies immediately, “Go to immigration office and find out where they are. Has Buddy heard anything? Did he say they got on the flight?”

We had been over this before, but I reassured her, again, “Yes, as far as Buddy knows they boarded in Paris. Will go and see what I can find out.”

When I get to the airport Customs and Immigration office, they seem to be expecting me, which both reassures and alarms me. A young female officer shows me to a small room with a few chairs and a table in the middle – one of those rooms you see in movies where suspects are interrogated. There is no one else in the room. She invites me to sit and asks if I would like some water.

“This will probably take a while,” she explains, and suggests that I get as comfortable as possible. I accept this small kindness, take off my coat and drape it over a chair and sit down at the table, my “Amir” sign face down; I now realize that it will no longer be needed.

One more text to Anna, mostly to get a little peace and think things through: “Something going on. Think they are here. Will let you know,” then put my phone away and settled in for the wait. How is it I came to be sitting in a tiny windowless room in the Montreal Airport, prepared to break international law and anxious to meet complete strangers who I have already started to think of as family? It is hard not to smile despite my worry, as I think about the long winding road that led me to this stuffy little room in Canada.

Cherise, 1958 and 2017

Buddy delivered the news flat and quiet, like he was telling us it might rain tomorrow: “Mamma’s dead. Daddy shot her.”

A neighbor lady had informed our brother of this momentous event soon after it happened, down at the highway grocery and feed store where Buddy liked to sit and watch the world go by.

It was dark in our house, except for a flickering kerosene lantern. And quiet too, no wind off the water on the one side or rattle from the bare cornfields on the other. All four of us younger kids were jammed onto the broken-down couch in our shotgun shack, asleep in a big pile just a few minutes before. We looked expectantly up at Buddy, who did not seem upset or even sad, though he bore a slight hint of urgency in his eyes.

We sat quietly, Peanut on my lap, his constant dusty-urine smell blending into the usual wood stove and kerosene odor that we all knew as home. Roy and Billy were on either side, looking from Buddy to me, faces blank, waiting for the what now.

Though I can recall the smells and the flickering light clearly, I do not remember Buddy giving us any more details about how or where or why our father had shot our mother. The essential facts as shared by Mrs. Jenkins were enough, and by this point in our lives we all had a pretty good idea of how things worked with our parents. That night probably just seemed like the inevitable conclusion to the slapping and yelling and crying that defined their marriage and our every-day lives. If it hadn’t happened that night it would be some other night, sometime soon, after too many drinks and too far along for either to turn back. We all also knew that the where and why details of what had transpired at the roadhouse certainly would not change anything moving forward and so did not much matter.

Roy started to whimper a little and I stopped this by cutting my eyes at him, then I told Buddy, “You best go call Clarence.” Our big brother would be the only one to tell us what we would need to do.

As I think back these many years to when, at thirteen years old, I first learned of the instantaneous loss of both parents, in our beat-up shack of a house in a beat-up little village on the beat-up hot and dusty southern end of the Eastern Shore of Virginia in 1958, the only thing that surprises my adult self is how not surprised I actually was at the time. Or even really that scared. That my father shooting my mother in a drunken rage was not exceptional to any of us kids was a testament to how well they had prepared their children to live with chaos and violence, the unexpected and unpredictable.

Mamma and Leroy had blessed us with the adaptive skill to move quickly from the terrible to the what now, not a bad life lesson when you take a few giant steps back and think about it. I can almost laugh out loud, thinking that those two could or would have cooked-up this grand parenting scheme in order to help us deal with an unpredictable world, and that their final lesson, staged at a roadhouse with a twenty-two caliber pistol, was planned for our ultimate benefit.

Of course those two did not plan anything beyond what to have for breakfast on any given day once they finally woke up -- if some kind of edible fixings were even available in our pitiful kitchen. Neither one of them read the Good Housekeeping “How to be a Good Parent,” handbook, that is for sure. I remember how they would both act completely surprised and put-out when someone – from school or church, or heaven forbid, one of us – expected something resembling whatever it was that a loving or even just responsible parent might provide for their spawn. We were routinely sent to school with nothing to write with, much less eat. Thank goodness for the pitying teachers and school secretary who looked out for us once we got there.

But, irony of ironies, it turns out that Momma and Daddy actually did give us this one lasting gift, the skill to turn on a dime in the face of tragedy or pain, of being able to look away from the turmoil, violence or just plain bad news and prepare ourselves for what comes next. The big thing is, once you ask the question you have to answer it your own self. No hand-wringing or woe-is-me nonsense from the Taylor children. We learned early to get on with life, good or bad, though of course none of us kids would understand this strange gift as we sat on that busted couch that night, hearing that Daddy had shot Momma in the face.

I cannot say exactly how well this granite-hard lesson has helped Buddy, Billy, Clarence or Otis, though I think it did. And for me, I have harvested those carelessly sown seeds every day of my working life, helping myself and others put one foot in front of the other in the struggle that is life. Thank you Mamma and Leroy.

Poor Roy was another story altogether, the only one who did not seem to benefit much from Momma and Daddy’s parenting style. He was one to be thrown off kilter at the least little thing, even after we left home and the Shore - though to be fair Roy was maybe deeper than the rest of us in some ways. And maybe he did not have the gift of being able to fool himself when things looked bad, like most folks can. Everything mattered to Roy and he was somehow programmed to hold onto more of his everyday burdens than the rest of us, a heavy bag of stones getting bigger and bigger over the years. He had more to wrestle with than the rest of us combined.

I often wonder about Roy and what made him so different and maybe if he had had a little more time he would have figured out that he did not need to drag that sorry sack of rocks with him everywhere he went. Momma and Daddy’s unintended educational process was certainly a little too much for his tender heart, that's for sure.

Me and the others have come through to the other side, somehow benefiting from the hard, slap-in-the-face lessons of our parents, not better exactly, but stronger. We came up expecting little from the world and other people, beyond that most folks weren’t to be trusted and any situation could get messy and uncertain, if not downright violent. In that mean crucible we kids did learn to depend on each other in ways that most children probably never dream of. And in the process of managing all the what nows that have fallen in our paths, we also came to learn that a hard shell was survival’s most important ingredient, though it keeps the rest of the world, and frequently love in its many forms, at arm’s length. I am still learning how to live with this hard side of myself, even after all these years.

Life’s lessons are not like a final exam, over when the bell rings and you put your number two pencil back on your desk. They keep coming at you, those lessons, and it helps to wake up every day and remember who you are and how you got made the way you are and that you have gotten through worse before. It’s a daily trial that can almost wear a person out.

Leo, 1958

“Is this Mr. Antanucci? We got a young colored boy driving your truck trying to cross the bridge, says he works for you.”

Leo re-positioned himself on the side of the bed, sensing that he was going to need to be sharp, and listened to the caller, who continued, “Is this Mr. Antanucci?”

“Yep, this is me,” Leo acknowledged and cleared his throat.

“This colored boy work for you? What work is he doin’ at two a.m.? Truck’s empty by the way.”

These words finished pulling Leo from a deep sleep. Anna was wide awake too, as she had pulled herself up to sit in the bed next to him, switching on the bedside light as she did so, knowing they would think more clearly in the light.

Leo had loved to box as a kid growing up in South Philly, a useful skill he had learned in the basement gym of the Parish Hall and one that he frequently used at school and in the neighborhood. He had even dreamed of growing up to be a professional boxer one day, though this had been quickly snuffed once he was sent to work for the family moving business at seventeen years old. He did retain some of the skills he learned in the ring and on the streets though. He knew to change directions quickly, to feint and attack, and to give a potential opponent a little room to show what he had – time to even figure out if it would be fighting or talking that would resolve the conflict. As the last of nine children he had also learned to be quiet when others were yelling, and wait out the louder voices in the room before he committed his words, or his fists. Though awoken by the plaintive two a.m. ring phone and very much in the dark regarding circumstances, Leo could tell that the man on the other end of the line was definitely foe, not friend.

Leio stiffened as he finished waking-up, and was ready to deal with whatever this was all about as he did with any confrontation: methodically, waiting for the other guy to commit to his next move before speaking or acting. This is how he, and now he and Anna, had arrived at this grand point in life, the struggling owners of a small moving company in Baltimore, Maryland: a refugee from his sprawling and controlling family in Philadelphia, the real Antanucci and all five of his other Sons, a loud and pushy group who he loved and hated in equal measure.

Leo was able to surmise a few things in the first few seconds of the call. The man on the phone was likely a person of minimal authority, maybe not so smart and likely prone to bad decisions and easy prey to flattery. He also knew that Clarence had access to his one and only truck, so the, “colored boy,” was likely Clarence. “The Bridge,” was probably the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, since that is how folks referred to it after it had opened a few years ago, marvel that it was. He started to get his footing.

“Well thank you for calling me sir!” he said as cheerfully as he could muster. “Can you give me some more specific details? Who are you exactly?” Leo paused, and not getting a response continued, “And about my truck and this man who is driving it? Do you have a name? Are you sure it’s my truck? Is anyone else in the truck?” Still no reply though he could hear voices in the background on the other end of the phone line. Leo pressed on, “Which way was he headed when you stopped him?”

The caller took a deep breath, impatient with having to explain himself: “Toll Police, Bay Bridge. Stopped him after he paid the toll for the bridge. Going to the Shore. Truck says 'Antanucci And Sons, Baltimore, Maryland,' big as life, this phone number underneath. How do you think I knew where to call?” His volume increased as he continued, “Clarence Taylor is the nigger, no one else with him. Truck’s empty. Says he works for you, seems like he is hiding somethin’,” and then with a hint of accusation in his voice, “and sounds like you don’t know that he is supposed to be over our way.”

Leo now had a picture in his mind’s eye: he could see Clarence standing next to the truck in the dark, pulled over past the bridge toll booth, uniformed officers, nearby. The caller is in a small lighted office with other officers who think they are more important than they really are, excited that they are finally onto something more serious than an unpaid toll, probably even breaking up a case of grand larceny. Clarence is no doubt standing dead still, calm, watching everyone closely, his face blank as always - like the Sphinx, Anna has described him, unreadable as stone. Clarence did indeed work for Leo, and that certainly sounded like his one and only truck. But Leo did not have any idea why Clarence was headed east on the Chesapeake Bay Bridge at two a.m. on a Sunday morning in April. It was very clear to Leo, however, that what he said next could change his employee’s life inexorably.

Doing the cost-benefit calculations in his head, Leo took a deep breath as he got his footing.

While he did not know what Clarence was up to, he did know that he had worked hard as the only employee for the son-less Antanucci And Son’s Moving Company for over a year, never missing a day of work or complaining about overtime and weekend work, and never taking anything that did not belong to him. The two of them had humped a lot of furniture up narrow brownstone stairways, with one of them taking the dead man side of a dresser or side board and trusting the other. On a couple of occasions Leo had seen scars peeking out from Clarence’s wife beater as they coaxed something big up a few flights of stairs, Leo on the low end; something private and painful under that shirt. Clarence was tight lipped about his family and his past and Leo had quickly learned not to press for details when making conversation.

There were other things that Leo had learned over the past year that Clarence had worked for him, details shared in small measure, sometimes to Leo’s surprise. One day Clarence climbed into the truck and had wordlessly placed a manila envelope on the seat between them. Halfway through the workday Leo finally asked, “So what’s in the envelope?” And Clarence had carefully, almost reverentially removed a newly minted high school equivalency diploma with, “Clarence Taylor,” printed at the top. By way of explanation Clarence had only said, “I thought you might want to know about your employee’s education level,” and Leo could see the smallest hint of a smile on Clarence’s face.

Leo also knew that Clarence had a very pregnant wife, Vonda, who had been presented to him in a similarly understated manner, in her pre-pregnant state. One morning as the work day was about to start, he found Clarence standing next to the truck with a thin and very beautiful girl he had never seen or heard mention of before. She was introduced by Clarence: “Mr. Antonucci, this is Vonda, my wife. We got married yesterday.” Vonda had smiled at Leo and after a few seconds of silence tentatively reached her hand out to shake his. Leo looked from Clarence, who again sported only a slight lopsided grin, to Vonda, who was a bit more generous with her smile. When his surprise had abated, Leo finally reached up, engulfing her thin hand in both of his, conveying his warmth and congratulations, then took Clarence’s and did the same. Leo had suggested to Clarence that he take the day off to celebrate, but he and Vonda both shook their heads, Clarence only saying, “No sir. We got a job today don’t we?”

And finally, Leo knew that Clarence and Vonda lived in a back corner of Antanucci And Son’s garage, a hole-in-the wall he used for storage and a place to park the truck in downtown Baltimore. Clarence and he had banged up some very thin walls around the only window in the place, and the partitions, made of patched together plywood, two by fours and cardboard had been decorated on the inside by Vonda like it was a real home, even though it was open to the noise and smells of the rest of the Antanucci And Son’s garage. Leo guessed that Vonda was there right now, in their cardboard bedroom on the narrow bed, wide awake, and that she was no doubt even more worried about whatever it was her husband was getting up to than him. It was clear that something truly serious must be on the line for Clarence.

Beyond these thoughts about Clarence and Vonda, Leo also knew that that a bigger reality loomed over all other calculations: that in 1958 a black man with a stolen moving van in the hands of a white man with authority -- and the less real authority the worse it would be – would not fare well. It would not matter to the toll cop if there even was such a thing, or the real police or even to a real judge, that Clarence was a reliable employee who kept a clean nose and loved his wife and made a home out of a dusty and drafty garage, if it was revealed that Clarence had, technically, stolen the truck. Leo took a deep breath, sat up a little straighter, then delivered a dose of bullshit that he hoped would lead to the least amount of damage to the fewest people, even if he never saw that truck again.

“Yes sir! Thank you for doing such a great job,” he declared. “Why yes, Clarence Taylor is in fact my most valuable employee and he is headed to the Shore for an emergency pick-up. I was dead asleep when you called and wasn’t putting two and two together at first.” Leo paused, heard a grunt in his ear and continued, “ Thank you very much! Didn’t know my employee would be leaving so early, but that is just like him! I told the lady we would be there Sunday morning and I guess Clarence wanted to be there at sunrise.” Leo paused, heard another grunt, and continued, “Just like him. Thank you for your concern, but Clarence can go on his way.”

On the other end of the line Leo could hear more background conversation and then disappointment in the man’s voice when he spoke: no more fun tonight. “Awright, we’ll turn him loose. You might want to give him a letter or somethin’ next time to save us all a lot of trouble.”

Although this was the stupidest thing this stupid man had said so far, Leo responded with a honey-dipped, “You are so right sir, good idea. Sorry I did not think of it this time around, will do so next!” he ended brightly, but simultaneously imagined giving the man a short sharp punch to his mid face.

After hanging up the phone, Leo turned to where Anna was sitting up in bed, waiting. She had heard his end of the call and likely had figured out most of the story. She searched his face but did not speak. “Clarence took the truck and is headed east on the Bay Bridge,” he sighed. “Not stealing it, I don’t think. Truck is empty and he is alone.” Leo rubbed his head with both hands, and shook it slightly to banish the rest of the sleep from his brain. “There is something going on with Clarence and I don’t want to jump the gun, but sure do wish that boy had told me what he was going to borrow the truck for a midnight run.” Leo rose and put on his green Antanucci And Son’s uniform slowly and leaned down to kiss Anna on the forehead. “I better go down to the garage and check on Vonda.”

Cherise, 2017

It has been an hour in this hot little room. I wish someone had thought to ask me if I needed to go to the lady’s room before I plunked down in this uncomfortable chair.

“Anybody need to pee?” Ha! A simple question that get asked in my family with some regularity and always with a laugh. And it’s a question with a simple solution. I should not have accepted that glass of water and now my passport, driver’s license and cell phone have been seized without a good explanation, just, “No, you don’t need a lawyer, ma’am,” and no way to get Buddy’s help unless Anna has figured out that we need him. Next stop may be the Canadian FBI.

Boy, do I need to pee. I performed a thought exercise in my head, to kill time but also to distract me from both my bladder and the worry of the moment. If I were to write the story of my life what kind of a story would it be that had me end up in this little room? A novel would be more fun than a biography, but what kind of novel? It was Shakespeare I think who said there were only seven stories that man could tell: comedy, tragedy, rags to riches, kill the monster. Can’t remember the rest. Not sure what my plot line could be of those I can remember? Maybe all of them?

An account of my life could be a coming-of-age kind of story. Problem is, most of these types of stories only chronicle a very short period in a person's life, usually a child or teen who gets some tough lessons and then comes through on the other side a little wiser and one step closer to adulthood. And adulthood usually implies a certitude about life despite its many crazy curve balls that has somehow eluded me for many decades. My life – and probably most folk’s lives – just aren’t that formulaic.

It has always seemed artificial and downright untrue when I watched a movie or read a novel with this story line, that somehow we get to a place where we are absolutely sure of ourselves, our world and how we fit in it. I am in my seventies now and still don’t have it figured out, though ninety-nine out of a hundred on-lookers would guess that I had a rock solid sense of self and place in the world. My life still feels like a work in progress, and yet I would have thought I would have arrived at that certitude place by now.

My theory is that we all – all of us pitiful people in the world – remain a little unsure, insecure about who we are and how we fit in, throughout our entire lives. But it is the rare person who can admit this, even to themselves. We just get better at faking our assuredness, using bluster or the bully pulpits of age and financial security to bluff our way through the confusing daily mess that is life. Anyway, who wants to hear about how an old lady comes of age? Sounds like a boring story, that in this case involves a weak bladder and a poorly conceived plan to make a difference to someone or something bigger than her own little world.

<h2> <h2> <h2>Clarence, 1958

Clarence let his breath escape slowly, not letting any of the officers see a crack in what he thought of as his Wall – the face, posture, clothing, walk, tone of voice – all the things he had to do every day that helped keep him safe from the world at large, and particularly from white men in charge of something he needed or somewhere he needed to be, or worse, angry at him for simply being a negro who had the audacity to want or need, or to travel at will. The game was always rigged and he knew that his life and family could be changed forever at the whim of such a stranger.

He turned to face them, smiled and said, “Thank you sir,” when one of the two toll policemen said, “Boy, you can get out of here now.” He then whispered a more sincere second thanks for Mr. Antanucci, who clearly had enough faith in him to allow his ill-formed plan to proceed.

Clarence quickly climbed back up into the cab of the truck and cranked it up. He released a bigger sigh when he put the truck in gear and started up the long ramp to the bridge. It was the darkest part of the night and there was no breeze, which he appreciated as the Bay winds could push cars around on the bridge. More than once he had read stories in the Baltimore Sun about head-on collisions when a vehicle got blown into oncoming traffic in the next lane. People still weren’t used to driving on the bridge, and, like him, many were making their first nervous crossings.

He remembered the wind jostling the Greyhound bus around the only other time he had been on the bridge, traveling north and west, when he had left the Shore two Christmases past. There had been nervous laughter by some of the passengers as the bus swayed, but he and the only other negro passenger didn’t laugh. Clarence could not tell if the other man was nervous or had made the trip a hundred times and was used to the wind pushing the bus like a toy. His Wall was up too, looked like, safest to keep even another negro outside and guessing.

As he now crossed the apex of the bridge Clarence hoped the wind would hold off for a good four or five hours. The moving truck had a tall profile and he did not want to get blown around on the trip back. That first crossing seemed like a lifetime ago now, and though he had expected to one day return home to the long finger of the Delmarva Peninsula, he thought and hoped that it would be after he finished making his new life, when he had become the new Clarence Taylor, so he could be like a tourist visiting his old town and friends and family, rather than as himself, the boy who grew up in that dust and heat and on the worn-out tired dreams that seemed to be the only thing that kept people there living from one day to the next.

Events earlier that evening had conspired against this imagined future though, when Buddy called on the Antanucci And Son’s garage phone line, the number he had sent to Cherise and Buddy when he and Vonda had first moved into the garage. The only calls they had ever gotten were from Leo or Anna, until this night, and Clarence’s surprise quickly yielded to worry.

The details shared by Buddy did not surprise him any more than it had his siblings. Once again his damaged, crazy, beautiful mother and angry, mean spirited and generally sorry stepfather had put him on a path that was not of his choosing. What now, he thinks, not a question but a statement. Questions have answers. There was no answer tonight except to head east until he got to the ocean, then south until he reached the end of the world that is the Eastern Shore of Virginia.

He would do what he usually did when life threw him onto a dark path into a darker forest: figure things out as he went, try to do the right thing at each turn, and hope for the best. Until tonight he would say of his choices and his stab at manhood and independence, “So far so good.” It did seem like he picked the right path most of the time, that he moved forward and toward becoming the new Clarence Taylor, his own Clarence Taylor.

Tonight he was not so sure, how to deal with a Now that had been thrown by a drunk Leroy onto his brothers and sister like a bucket of stinking, muddy water from the low tide creek behind the shack they called home. This murky mess had then splashed right onto him as well, and the only thing he was certain of now was that he had to get to Cherise, Buddy, Billy and Roy before the police and some social worker got to them first. He knew that they would be pulled apart and thrown to the winds and that the only people that he loved and called family, beside Vonda, would be lost.

When Buddy had called a few hours earlier and had finished sharing his grim news, Clarence walked from the greasy garage desk, sat down on the narrow bed next to Vonda and took her hand in his, looking down at his bare feet. He shared the news with her in much the same way that Buddy had shared it with the younger kids, but added the only plan he could imagine: “My momma is dead; Leroy shot her. I gotta go see to the kids.” Vonda nodded, gripped his hand more tightly, and had said only, “Baby, go. But come back, we need you,” as he left the garage. Clarence knew she meant go and do what he needed to do, and then come back. Neither of them had any idea what this could or would entail.