Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

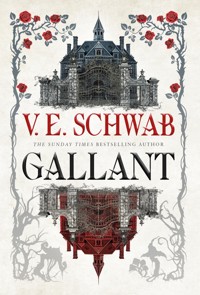

The Number 1 Sunday Times-bestselling novel, from the author of The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue, and A Darker Shade of Magic. A darkly magical and thrilling tale of a young woman caught between the world and its shadows, who must embrace her legacy to stop the approaching darkness. The Secret Garden meets Crimson Peak, perfect for fans of Neil Gaiman, Holly Black and Susan Cooper. Fourteen-year-old Olivia Prior is missing three things: a mother, a father, and a voice. Her mother vanished all at once, and her father by degrees, and her voice was a thing she never had to start with. She grew up at Merilance School for Girls. Now, nearing the end of her time there, Olivia receives a letter from an uncle she's never met, her father's older brother, summoning her to his estate, a place called Gallant. But when she arrives, she discovers that the letter she received was several years old. Her uncle is dead. The estate is empty, save for the servants. Olivia is permitted to remain, but must follow two rules: don't go out after dusk, and always stay on the right side of a wall that runs along the estate's western edge. Beyond it is another realm, ancient and magical, which calls to Olivia through her blood…

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 320

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Also Available from V.E. Schwab and Titan Books

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

Part 1: The School

1

2

3

4

Part 2: The House

5

6

7

8

9

10

Part 3: Things Unsaid

11

12

13

14

15

Part 4: Beyond the Wall

16

17

18

19

20

21

Part 5: Blood and Iron

22

23

24

25

26

27

Part 6: Home

28

29

30

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

ALSO AVAILABLE FROMV.E. SCHWAB AND TITAN BOOKS

The Near Witch

Vicious

Vengeful

This Savage Song

Our Dark Duet

The Archived

The Unbound

A Darker Shade of Magic

A Gathering of Shadows

A Conjuring of Light

The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue

ALSO AVAILABLE FROMV.E. SCHWAB AND TITAN COMICS

Shades of Magic: The Steel Prince

Shades of Magic: The Steel Prince – Night of Knives

Shades of Magic: The Steel Prince – Rebel Army

ExtraOrdinary

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

GALLANT

Hardback edition ISBN: 9781785658686

Forbidden Planet edition ISBN: 9781803361284

Waterstones edition ISBN: 9781803361260

Illumicrate edition ISBN: 9781803361291

WHS edition ISBN: 9781803361581

Export edition ISBN: 9781789098938

Australian export edition ISBN: 9781803360355

Eire export edition ISBN: 9781803361277

Indian export edition ISBN: 9781785658709

E-book edition ISBN: 9781785658693

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: March 2022

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

© V.E. Schwab 2022. All rights reserved. V.E. Schwab asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

To those who go looking for doors,are brave enough to open the ones they find,and sometimes bold enough to make their own.

The master of the house stands at the garden wall.

It is a grim stretch of stone, an iron door locked and bolted at its center. There is a narrow gap between the door and the rock, and when the breeze is right, it carries the scent of summer, sweet as melon, and the distant warmth of sun.

There is no breeze tonight.

No moon, and yet he is bathed in moonlight. It catches the edges of his tattered coat. It shines on the bones where they show through his skin.

He trails his hand along the wall, searching for cracks. Stubborn strands of ivy follow in his wake, questing like fingers into every fissure, and nearby a bit of stone breaks free and tumbles to the ground, exposing a narrow slice of someone else’s night. The culprit, a field mouse, scrambles through, and then down the wall, over the master’s boot. He catches it in one hand, with all the grace of a snake.

He bends his head to the crack. Fastens his milk-white eyes on the other side. The other garden. The other house.

In his hand, the mouse squirms, and the master squeezes.

“Hush,” he says, in a voice like empty rooms. He is listening to the other side, to the soft chirp of birdsong, the wind through lush leaves, the distant pleading of someone in their sleep.

The master smiles and picks up the bit of broken rock and nestles it back into the wall, where it waits, like a secret.

The mouse has stopped squirming in the cage of his grip.

When he opens his hand, there is nothing left but a streak of ash and rot and a few white teeth, little bigger than seeds.

He tips them out onto the wasted soil and wonders what will grow.

Rain drums its fingers on the garden shed.

They call it a garden shed, but in truth there is no garden on the grounds of Merilance, and the shed is barely even that. It sags to one side, like a wilting plant, made of cheap metal and moldering wood. The floor is littered with abandoned tools and shards of broken pots and the stubs of stolen cigarettes, and Olivia Prior stands among them in the rusted dark, wishing she could scream.

Wishing she could turn the pain of the fresh red welt on her hand into noise, overturn the shed the way she did the pot in the kitchen when it burned her, strike the walls as she longed to strike Clara for leaving the stove on and having the nerve to snicker when Olivia gasped and let go. The white-hot pain, the red-hot anger, the cook’s annoyance at the ruined mash, and Clara’s pursed lips as she said, “It couldn’t have hurt that much, she didn’t make a sound.”

Olivia would have wrapped her hands around the other girl’s throat right there if her palm weren’t singing, if the cook weren’t there to haul her off, if the gesture would have gained her more than a moment’s pleasure and a week’s punishment. So she’d done the next best thing: stormed out of the stuffy tomb, the cook bellowing in her wake.

And now she’s in the garden shed, wishing she could make as much noise as the rain on the low tin roof, take up one of the neglected spades and beat it against the thin metal walls, just to hear them ring. But someone else would hear, would come and find her, in this small and stolen place, and then she’d have nowhere to get away. Away from the girls. Away from the matrons. Away from the school.

She holds her breath and presses her burned hand against the cool metal shed, waiting for the ache in her skin to quiet.

The shed itself is not a secret.

It sits behind the school, across the gravel drive, at the back of the grounds. Over the years, a handful of girls have tried to claim it as their own, to smoke or drink or kiss, but they come once and never come back. It gives them the creeps, they say. Damp soil and spiderwebs, and something else, an eerie feeling that makes the hair stand up on their necks, though they don’t know why.

But Olivia knows.

It is the dead thing in the corner.

Or what’s left of it. Not a ghost, exactly, just a bit of tattered cloth, a handful of teeth, and a single, sleepy eye floating in the dark. It moves like a silverfish at the edge of Olivia’s sight, darting away every time she looks. But if she stays very still and keeps her gaze ahead, it might grow a cheekbone, a throat. It might drift closer, might blink and smile and sigh against her, weightless as a shadow.

She has wondered, of course, who it was, back when it had bones and skin. The eye hovers, higher than her own, and once she caught the edge of a bonnet, the fraying hem of a skirt, and thought, perhaps, it was a matron. Not that it matters. Now, it is only a ghoul, lurking at her back.

Go away, she thinks, and perhaps it can hear her thoughts, because it flinches and draws back into the dark again, leaving her alone in the grim little shed.

Olivia leans back against the wall.

When she was younger, she liked to pretend that this was her house, not Merilance. That her mother and father had just stepped out and left her to clean up. They would be coming back, of course.

Once the house was ready.

Back then, she’d sweep away the dust and cobwebs, stack the pot shards and make order of the shelves. But no matter how tidy she tried to make the little shed, it was never clean enough to bring them back.

Home is a choice. Those four words sit alone on a page in her mother’s book, surrounded by so much white space they feel like a riddle. In truth, everything her mother wrote feels like a riddle, waiting to be solved.

By now, the rain has slowed from pounding fists to the soft, infrequent tapping of bored fingers, and Olivia sighs and abandons the shed.

Outside, everything is gray.

The gray day is beginning to melt into a gray night, thin gray light lapping against the gray gravel path that surrounds the gray stone walls of Merilance School for Independent Girls.

The word “school” conjures images of neat wooden desks and scratching pencils. Of learning. They do learn, but it is a perfunctory education, spent on the practical. How to clean a fireplace. How to shape a loaf of bread. How to mend someone else’s clothes. How to exist in a world that does not want you. How to be a ghost in someone else’s home.

Merilance may call itself a school, but in truth, it is an asylum for the young and the feral and the fortuneless. The orphaned and unwanted. The dull gray building juts up like a tombstone, surrounded not by parks or rolling greens but the gaunt and sagging faces of the other structures at the city’s edge, chimneys wheezing smoke. There are no walls around the place, no iron gates, only a vacant arch, as if to say, You’re free to leave, if you have somewhere else to go. But if you go—and now and then, girls do—you will not be welcomed back. Once a year, sometimes more, a girl pounds at the door, desperate to get back in, and that is how the others learn that it’s well and good to dream of happy lives and welcome homes, but even a grim tombstone of a place is better than the street.

And yet, some days Olivia is still tempted.

Some days, she eyes the arch, yawning like a mouth at the gravel’s edge, and thinks, what if, thinks, I could, thinks, one day I will.

One night, she will break into the matrons’ rooms and take whatever she can find and be gone. She will become a vagabond, a train robber, a cat burglar, or a con artist, like the men in the penny dreadfuls Charlotte always seems to have, tokens from a boy she meets at the edge of the gravel moat each week. Olivia plans a hundred different futures, but every night, she is still there, climbing into the narrow bed in the crowded room in the house that is not, and will never be, a home. And every morning she wakes up in the same place.

Olivia shuffles back across the yard, her shoes sliding over the gravel, with a steady shh, shh, shh. She keeps her eyes on the ground, searching for color. Now and then, after a good hard rain, a few green blades will force their way up between the pebbles, or a stubborn sheen of moss will latch onto a cobblestone, but these defiant colors never last. The only flowers she sees are in the head matron’s office, and even those are fake and faded, silk petals long gone gray with dust.

And yet, as she rounds the school, heading for the side door she left ajar, Olivia sees a dash of yellow. A little weedy bloom, jutting up between the stones. She kneels, ignoring the way the pebbles bite into her knees, and brushes a careful thumb over the tiny flower. She’s just about to pluck it when she hears the stomp of shoes on gravel, the familiar rustle and sigh of skirts that signal a matron.

They look the same, the matrons, in their once-white dresses with their once-white belts. But they’re not. There’s Matron Jessamine, with her tight little smile, as if she’s sucking on a lemon, and Matron Beth, with her deep-set eyes and the bags beneath, and Matron Lara, with a voice as high and whining as a kettle.

And then, there’s Matron Agatha.

“Olivia Prior!” she booms, in a breathless huff. “What are you doing?”

Olivia lifts her hands, even though she knows it’s futile. Matron Sarah taught her how to sign, which was well and good until Matron Sarah left and none of the others bothered to learn.

Now it doesn’t matter what Olivia says. No one knows how to listen.

Agatha stares at her as she shapes planning my escape, but she’s only halfway through when the matron flaps her own hands, impatient.

“Where—is—your—chalkboard?” she asks, speaking loud and slow, as if Olivia is hard of hearing. She is not. As for the chalkboard, it’s wedged behind a row of jam jars in the cellar, where it has been since it was first bestowed upon her, complete with a little rope to go around her neck.

“Well?” demands the matron.

Olivia shakes her head and picks the simplest sign for rain, repeating the gesture several times so the matron has a chance to see, but Agatha just tsks and grabs her wrist and hauls her back inside.

* * *

“You were supposed to be in the kitchen,” says the matron, marching Olivia down the hall. “Now it’s time for dinner, which you have not helped to make.” And yet, by some miracle, thinks Olivia, judging by the scent wafting toward them, it is ready.

They reach the dining room, where girls’ voices pile high, but the matron pushes her on, past the doors.

“Those who do not give, do not partake,” she says, as if this is a Merilance motto and not something she’s just thought up. She gives a curt little nod, pleased with herself, and Olivia pictures her stitching the words onto a pillow.

They reach the dormitory, where there are two dozen small shelves beside two dozen beds, thin and white as matchsticks, all of them empty.

“To bed,” says the matron, though it isn’t even dark. “Perhaps,” she adds, “you can use this time to reflect on what it means to be a Merilance girl.”

Olivia would rather eat glass, but she just nods and does her best to look contrite. She even curtsies once, bobbing her head low, but it is only so the matron cannot see the twist of her lips, the small, defiant smile. Let the old bat assume that she is sorry.

People assume a lot of things about Olivia.

Most of them are wrong.

The matron shuffles away, clearly not wanting to miss dinner, and Olivia steps into the dorm. She lingers at the foot of the first bed, listening to the rustle of receding skirts. As soon as Agatha has gone, she emerges again, slipping down the hall and around the corner to the matrons’ quarters.

Each of the matrons has her own room. The doors are locked, but the locks are old and simple, the teeth on the keys little more than simple peaks.

Olivia draws a bit of sturdy wire from her pocket, remembering the shape of Agatha’s key, the teeth a capital E. It takes a bit of fussing, but then the lock clicks, and the door swings open onto a neat little bedroom cluttered with pillows, little mantras embroidered across their fronts.

Here by the grace of God.

A place for all things, and all things in their place.

A house in order is a mind at peace.

Olivia’s fingers trail over the words as she rounds the bed. A little mirror sits on the windowsill, and as she passes, she catches a glimpse of charcoal hair and a sallow cheek, and startles. But it is just her own reflection. Pale. Colorless. The ghost of Merilance. That’s what the other girls call her. Yet there is a satisfying hitch in their voices, a hint of fear. Olivia looks at herself in the mirror. And smiles.

She kneels before the ash wood cabinet beside Agatha’s bed. The matrons have their vices. Lara has cigarettes, and Jessamine has lemon drops, and Beth has penny dreadfuls. And Agatha? Well. She has several. A bottle of brandy sloshes in the top drawer, and beneath that, Olivia finds a tin of cookies, iced with sugar, and a paper bag of clementines, bright as tiny sunsets. She takes three of the iced cookies and one piece of fruit, and retreats, silently, to the empty dorm to enjoy her dinner.

Olivia lays the picnic out atop her narrow bed.

The cookies she eats fast, but the clementine she savors, peels it in a single curl, the sunny rind unraveling to reveal the happy segments. The whole room will smell like stolen citrus, but she doesn’t care. It tastes like spring, like bare feet in grassy fields, like somewhere warm and green.

Her bed is at the far end of the room, so she can sit with her back to the wall as she eats, which is good, because it means she can keep her eye on the door. And the dead thing sitting on Clara’s bed.

This ghoul is different, smaller than the other. It has knobby elbows and knees and an unblinking eye, one hand tugging on a tatty braid as it watches Olivia eat. There is something girlish in the way it moves. The way it pouts, and tips its head, and whispers in her ear when she’s trying to sleep, soft and voiceless, the words nothing but air against her cheek.

Olivia scowls straight at it until it melts away.

That is the trick with the ghouls.

They want you to look, but they can’t stand being seen.

At least, she thinks, they cannot touch her. Once, in a fit of frustration, she flung her hand out at a nearby ghoul, but her fingers went straight through. No eerie draft against her skin, not even the breath of something in the air. She felt better then, knowing it was not real enough, not there enough, to do more than smile or scowl or sulk.

Beyond the door, the sounds are changing.

Olivia listens to the shuffle and scrape of dinner ending down the hall, the rap of the head matron’s cane as she stands to give her nightly lecture—on cleanliness, perhaps, or goodness, or modesty. Matron Agatha will be listening too, no doubt, ready to stitch the words onto a cushion.

From here, the speech is nothing but a rasp, a rustle—Anothermercy, she thinks as she brushes the crumbs from the bed and hides the sunny ribbon of the orange peel under her pillow, where it will smell sweet. She reaches for the trinkets on her shelf.

Every bed has a shelf, though the contents change. Some girls have a doll, passed on as charity or sewn themselves. Some have a book they like to read, or a bit of embroidery on a hoop. Most of Olivia’s shelf is taken up with sketchpads and a jar of pencils, worn short but sharp. (She is a gifted artist, and if the matrons of Merilance do not exactly nurture it, they don’t neglect it either.) But tonight her fingers drift past the sketchpads to the green journal sitting at the end.

It was her mother’s.

Her mother, who has always been a mystery, an empty space, an outline, the edges just firm enough to mark the absence. Olivia lifts the journal gently, running her hand over the cover, worn soft with age—the closest thing she has to a memory of life before Merilance. Olivia arrived at the grim stone tomb when she was not yet two, dirt-smudged in a dress trimmed with tiny wildflowers. She might have been out on the step for hours before they found her, they said, because she never cried. She doesn’t remember that. Doesn’t remember anything of the time before. She can’t recall her mother’s voice, and as for her father, she only knows she never met him. He was dead by the time she was born, that much she’s gleaned from her mother’s words.

It is a strange thing, the journal.

She has memorized every aspect, from the exact shade of green on the cover, to the elegant G scripted on its front—she has spent years guessing what it stands for, Georgina, Genevieve, Gabrielle—to the twin lines not pressed or scraped but gouged below it, perfect parallel grooves that run from one edge to the other. From the strange ink blooms that take up entire pages to the entries in her mother’s hand, some long and others only a handful of words, some lucid, and others cracked and broken, all of them addressed to “you.”

When Olivia was small, she thought that she was the “you,” that her mother was speaking to her across time, those three letters a hand, reaching through paper.

If you read this, I am safe.

I dreamed of you last night.

Do you remember when . . .

But eventually, she came to understand the “you” was someone else: her father.

Though he never answers, her mother writes on as if he has, entry after entry full of strange, veiled terms of their courtship, of birds in cages, of starless skies, writing of his kindness and her love and fear, and then, at last, of Olivia. Our daughter.

But there her mother begins to unravel. She begins to write of shadows crawling like fingers through the dark, and voices carried on the wind, calling her home. Soon her graceful script begins to tip, before tumbling over the cliff into madness.

That cliff? The night her father died.

He was ill. Her mother spoke of it, the way he seemed to wane as her belly waxed, some wasting sickness that stole him weeks before Olivia was born. And when he died, her mother fell. She broke. Her lovely words went jagged, the writing came apart.

I am sorry I wanted to be free sorry I opened the door sorry you’re not here and they are watching he is watching he wants you back but you are gone he wants me but I won’t go he wants her but she is all I have of you and me she is all she is all I want to go home

Olivia doesn’t like to linger on these pages, in part because they are the ramblings of a woman gone mad. And in part because she’s forced to wonder if that madness is the kind that lingers in the blood. If it sleeps inside her, too, waiting to be woken.

The writing eventually ends, replaced by nothing but a blank expanse, until, near the back, a final entry. A letter, addressed not to a father, living or dead, but to her.

Olivia Olivia Olivia, her mother writes, the name unravelling across the page, and her gaze drifts over the ink-spotted paper, fingers tracing the tangled words, the lines drawn through abandoned text as her mother fought to find her way through the thicket of her thoughts.

Something flickers at the edge of Olivia’s sight. The ghoul, nearer now, peers sheepishly over the mound of Clara’s pillow. It tilts its head, as if listening, and Olivia does the same. She can hear them coming. She shuts the journal.

Seconds later, the doors swing open and the girls pour in.

They chirp and chime as they spill across the room. The younger ones glance her way and whisper, but as soon as she looks back, they skitter past, like insects, to the safety of their sheets. The older ones do not look at all. They pretend she is not there, but she knows the truth: They are afraid. She has made sure of it.

Olivia was ten when she showed her teeth.

Ten, and walking down the hall, only to hear her mother’s words in someone else’s mouth.

“These dreams will be the death of me,” it said. “When I am dreaming, I know that I must wake. But when I wake, all I think about is dreaming.”

She reached the dorms to find silver-blonde Anabelle sitting primly on her bed, reading the entry to a handful of snickering girls.

“In my dreams, I am always losing you. In my waking, you are already lost.”

The words sounded wrong in Anabelle’s high lilt, her mother’s madness on full display. Olivia marched over and tried to take the journal back, but Anabelle darted out of reach, flashing a wicked grin.

“If you want it,” she said, holding the journal aloft, “all you have to do is ask.”

Olivia’s throat tightened. Her mouth opened, but nothing came out, just a rush of air, an angry breath.

Anabelle snickered at her silence. And Olivia lunged. Her fingers skimmed the journal, before two more girls pulled her back.

“Ah, ah, ah,” teased Anabelle, wagging a finger. “You have to ask.” She sidled closer. “You don’t even have to shout.” She leaned in, as if Olivia could simply whisper, shape the word please and set it free. Her teeth clicked together.

“What’s wrong with her?” sneered Lucy, scrunching up her nose.

Wrong.

Olivia scowled at the word. As if she hadn’t stolen into the infirmary the year before, hadn’t scoured the anatomy book, hadn’t found the drawings of the human mouth and throat and copied every single one, hadn’t sat up in bed that night, feeling along the lines of her own neck, trying to trace the source of her silence, trying to find exactly what was missing.

“Go on,” goaded Anabelle, holding the journal high. And when Olivia still said nothing, the girl flicked open the book that was not hers, exposing the words that were not hers, touching the paper that was not hers, and began to tear the pages out.

That sound, the ripping of paper from seam, was the loudest in the world, and Olivia tore free of the other girls’ hands and fell on Anabelle, fingers wrapped around her throat. Anabelle yelped, and Olivia squeezed until the girl could not speak, could not breathe, and then the matrons were there, pulling them apart.

Anabelle sobbed, and Olivia scowled, and both girls were sent to bed without supper.

“It was just a bit of fun.” The other girl sulked, collapsing onto her bed as Olivia silently, painstakingly, tucked the torn pages back into her mother’s journal, holding close the memory of Anabelle’s throat beneath her hands. Thanks to the anatomy book, she’d known exactly where to squeeze.

Now she runs her finger down the journal’s edge, where the torn pages stick out farther than the rest. Her dark eyes flick up as she watches the girls file in.

There is a moat around Olivia’s bed. That is what it feels like. A small, invisible stream that no one will cross, rendering her cot a castle. A fortress.

The younger girls think she is cursed.

The older ones think she is feral.

Olivia doesn’t care, so long as they leave her alone.

Anabelle is the last one in.

Her pale eyes dart to Olivia’s corner, one hand going to her silver-blonde braid. Olivia feels a smile rise to her lips.

That night, after the torn-out pages were safely back inside their book, after the lights were out and the girls of Merilance were all asleep, Olivia got up. She crept into the kitchen, and took an empty mason jar, and went down into the cellar, the kind of place that is somehow always dry and damp at once. It took an hour, maybe two, but she managed to fill the jar with beetles, and spiders, and half a dozen silverfish. She added a handful of ash from the head matron’s hearth, so the little bugs would leave their mark, and then she crept back into the dormitory and opened the jar over Anabelle’s head.

The other girl woke screaming.

Olivia watched from her bed as Anabelle pawed at the sheets and tumbled out onto the floor. Around the room, the girls all shrieked, and the matrons came in time to see a silverfish wriggle out of Anabelle’s braid. Nearby, the ghoul watched, shoulders bobbing in a silent chuckle, and as Anabelle was led sobbing from the room, the ghoul held up a bony finger to its half-formed lips, as if vowing to keep the secret. But Olivia didn’t want it to be a secret. She wanted Anabelle to know exactly who’d done it. She wanted her to know who made her scream.

By breakfast, Anabelle’s hair had been lopped short. She looked straight at Olivia, and Olivia stared back.

Go on, she thought, holding the other girl’s gaze. Say something.

Anabelle didn’t.

But she never touched the journal again.

It’s been years now, and Anabelle’s silver-blonde hair has long grown back, but she still touches the braid every time she sees Olivia, the way the girls are told to cross themselves or kneel at service.

Every time, Olivia smiles.

“Into bed,” says a matron—it doesn’t matter which. And soon the lights go out, and the room is still. Olivia climbs beneath the scratchy blanket and curls her spine into the wall and hugs the journal to her chest and closes her eyes against the ghoul and the girls and the world of Merilance.

Olivia has been buried alive.

At least, that is how it feels. The kitchen is such a stuffy place, in the bowels of the building, the air clogged with pot steam and the walls made of stone, and whenever Olivia is forced to work in here, she feels as if she’s been entombed. She wouldn’t mind it so much, if she were alone.

There are no ghouls down in the kitchen, but there are always girls. They chitter and chat, filling the room with noise, just because they can. One is telling a story about a prince and a palace. One is moaning about cramps, and the other sits on the counter, swinging her legs and doing absolutely nothing.

Olivia tries to ignore them, focusing instead on her bowl of potatoes, the paring knife glinting dully in her palm. She studies her hands as she works. They are thin, unlovely but strong. Hands that can speak, though few at the school bother to listen, hands that can write and draw and stitch a perfect line. Hands that can part skin from flesh without slipping.

There is a small scar, between her finger and thumb, but that was a long time ago, and it was her own doing. She had heard the other girls holler when they hurt themselves. A sharp cry, a long wail. Hell, when Lucy tried to jump between the cots one day and missed and broke her foot, she bellowed. And Olivia had wondered, almost absently one day, if her voice lay on the other side of some threshold, if it could be summoned forth with pain.

The knife was sharp. The cut was deep. Blood welled and spilled onto the counter, and heat screamed up her arm and through her lungs, but only a short, sharp gasp escaped her throat, more emptiness than sound.

When Clara saw the blood, she yelped, a high disgusted noise, and Amelia called for the matrons, who assumed it was an accident, of course. Clumsy thing, they tutted and tsked, while the other girls whispered. Everyone, it seemed, so full of noise. Except Olivia.

She, who wanted to scream, not in pain but sheer exasperated fury that there was so much noise inside her, and she could not let it out. She’d kicked over a pile of pots instead, just to hear them clang.

Across the kitchen, the girls have turned to talk of love.

They whisper as if it’s a secret or a stolen sweet, palmed and kept inside their cheeks. As if love is all they need. As if they have been placed under a curse and only love will set them free. She does not see the point in that: love did not save her father from illness and death. It did not save her mother from madness and loss.

The girls say love, but what they really mean is want. To be wanted, beyond the walls of this house. They are waiting to be rescued by one of the boys who linger at the edge of the gravel moat, trying to lure them across.

Olivia rolls her eyes at the mention of favors and promises and futures.

“What would you know?” sneers Rebecca, catching the look. She is a reedy girl with eyes too small and too close. More than once, Olivia has drawn her as a weasel. “Who would want you?”

Little does she know, there was a boy that spring. He caught her coming from the shed. Their eyes met, and he smiled.

“Come talk to me,” he said, and Olivia frowned and withdrew into the house. But the next day, he was there again, a yellow daisy in one hand. “For you,” he said, and she wanted the flower more than his attention, but still she drifted across the moat. Up close, his hair caught like copper in the sun. Up close, he smelled of soot. Up close, she noticed his lashes, and his lips, with the distance of an artist studying her subject.

When he kissed her, she waited to feel whatever her mother had felt for her father, the day they met, the spark that lit the fire that burned their whole world down. But she only felt his hand on her waist. His mouth on her mouth. A hollow sadness.

“Don’t you want it?” he’d asked when his hand grazed her ribs.

She wanted to want it, to feel what the other girls felt.

But she didn’t. And yet, Olivia is full of want. She wants a bed that does not creak. A room without Anabelles or matrons or ghouls. A window and a grassy view and air that does not taste of soot and a father who does not die and a mother who does not leave and a future beyond the walls of Merilance.

She wants all those things, and she has been here long enough to know that it does not matter what youwant—the only way out is to be wanted by someone else.

She knows, and still, she pushed him away.

And the next time she saw the boy, at the edge of the yard, he was leaning toward another girl, a pretty little wisp named Mary, who giggled and whispered in his ear. Olivia waited for the flush of envy, but all she felt was cool relief.

She finishes skinning a potato and studies the little paring knife. Balances it on the back of her hand before flicking it gingerly into the air and catching the grip. She smiles, then, a small private thing.

“Freak,” mutters Rebecca. Olivia looks up, holds her eye, and wags the knife like a finger. Rebecca scowls and turns her attention to the other girls, as if Olivia is a ghoul, something to be ignored.

They move on from boys, at least. Now they are talking about dreams.

“I was at the seaside.”

“You’ve never been to the sea.”

“So what?”

Olivia takes up another potato, slides the knife under the starchy skin. She is almost done, but she slows her work, listening to them prattle.

“So how do you know it was the seaside and not a lake?”

“There were seagulls. And rocks. And besides, you don’t need to know about a place to dream of it.”

“Of course you do . . .”

Olivia quarters the spud and drops it in the pot.

They talk of dreams as if they’re solid things, the kind you might mistake for real. They wake with whole stories impressed upon their minds, images committed to memory.

Her mother spoke of dreams as well, but hers were crueler things, filled with dead lovers and clawing shadows, sharp enough that she felt the need to warn her daughter they were not real.

But her mother’s warning is wasted.

Olivia has never had a dream.

She imagines things, of course, conjures other lives, pretends she is someone else—a girl with a large family and a grand house and a garden bathed in sun, fanciful things like that—but not once, in fourteen years, has she been visited by dreams. Sleep, when it comes, is a dark tunnel, a shroud of black. Sometimes, right after she wakes, there is a kind of filament, like spider silk, clinging to her skin. That strange sense of something just out of reach, an image bobbing on the surface before rippling away. But then it’s gone.

“Olivia.”

Her name cuts through the air. She flinches, fingers tensing on the knife, but it is only the thin-faced matron, Jessamine, waiting at the door, lips pursed as if she’s got a lemon on her tongue. She crooks her finger, and Olivia abandons her station.

Heads swivel. Eyes follow her out.

“What has she done now?” they whisper, and honestly, she doesn’t know. It could have been the lockpicks she fashioned, or the sweets she stole from Matron Agatha’s drawer, or the chalkboard buried in the cellar.

She shivers a little as they climb the stairs, trading the stuffy kitchen for the chilly halls beyond. Her heart sinks at the sight of the head matron’s door. Never a good sign, to be summoned here.

Jessamine knocks, and a voice answers from the other side.

“Come in.”

Olivia clenches her jaw, teeth clicking softly together as she steps inside.

It is a narrow room. The walls are lined with books, which would be welcoming if they were stories of magic or pirates or