0,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

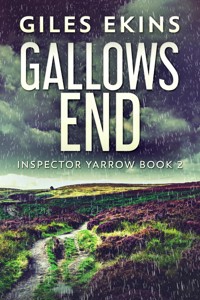

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

In 1950s United Kingdom, West Garside is a small, rather uneventful town. That is, until a bungled bank robbery leaves two people dead.

Former Battle Of Britain pilot and now detective, DI Christopher Yarrow is called in to lead the manhunt. Soon, a burnt out getaway car and some vital clues reveal more about the gunman's identity.

With every step, the killer seems to be a step ahead of Yarrow and his team. Can they find him, and bring him to justice before more lives are lost?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

GALLOWS WALK

INSPECTOR YARROW BOOK 1

GILES EKINS

CONTENTS

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Chapter 59

Chapter 60

Chapter 61

Chapter 62

Chapter 63

Chapter 64

Chapter 65

Chapter 66

Chapter 67

Chapter 68

Chapter 69

Chapter 70

Chapter 71

Chapter 72

Chapter 73

Chapter 74

Chapter 75

Chapter 76

Chapter 77

Chapter 78

Chapter 79

Chapter 80

Chapter 81

Chapter 82

Chapter 83

Chapter 84

Chapter 85

Chapter 86

Chapter 87

Chapter 88

Chapter 89

Chapter 90

Chapter 91

Chapter 92

Chapter 93

Chapter 94

Chapter 95

Chapter 96

Chapter 97

Chapter 98

Chapter 99

Epilogue

Dear Reader

Next in the Series

About the Author

Copyright (C) 2020 Giles Ekins

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2020 by Next Chapter

Published 2020 by Next Chapter

Cover art by CoverMint

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author’s permission.

For Patricia, as always

PROLOGUE

WEST GARSIDE. WEST RIDING OF YORKSHIRE, CIRCA 1954.

It was the same nightmare, the same nightmare he always had.

Trapped inside his doomed Hurricane fighter as it spiralled down towards the unforgiving, fatal ground below. The air flailed through the smashed canopy, battering his bloody face. He hauled back on the joystick, desperately trying to pull the stricken plane out of the deathly spin. Blood streamed down his face and into his eyes, and he could tell that bullets from the Messerschmitt 109 fighter had smashed into his cockpit, wounding his left leg and hand, the pain a searing, throbbing immensity of agony.

Desperately trying to control the spin, he screamed in pain as the crippled Hurricane slowly pulled out of the spin and into a shallow dive.

But the aircraft was still mortally wounded, and the reprieve was only temporary, a crash inevitable. The canopy was smashed and buckled, jammed tight, immovable; his goggles were shattered, impacting his vision as he vainly tried to wipe the blood away with his gloved hand.

The ground rushed beneath the plane as he frantically searched for a flat landing site, but the Hurricane was now unflyable, totally unresponsive to damaged controls and was headed straight towards a coppice of tall oak trees atop a mound, the only hillock, the only trees in an ocean of green Kentish fields.

The gallant, wounded Hurricane flew straight towards the trees, and there was nothing that Yarrow could do to avert the crash, when, as if guided by a Divine hand, the plane suddenly veered to the right, avoiding the menacing trees. He screamed as the plane smashed to the ground between the trees, entangled in tree trunks and branches—and all was blackness.

He awoke from the nightmare, waking as always in a heap of tangled sheets and blankets, his heart pounding, his body damp with sweat, his sightless eye throbbing with dull pain.

It was still dark as he stumbled across the bedroom and into the bathroom, fighting the urge to vomit. He washed his face in cold water and made his way downstairs. The house was still and quiet, but full of memories—memories of joy and the painful memories of loss, the ache still raw and crushing.

Detective Inspector Christopher Yarrow of the West Garside CID lit a Players cigarette, drawing the smoke deep into his lungs. He was a heavy smoker, even though he was aware of the dangers, having read a story in The Guardian newspaper confirming the Ministry of Health’s recent warnings that there was a link between smoking and lung cancer.

He filled the kettle and then brewed a pot of tea. There was a time when he would have reached for the whisky bottle rather than a teapot, but those drink-sodden days were now past. He now rarely drank—occasionally a beer or a glass of wine—but always with the realisation of how easy it would be to sink back into the slough of despond, to wallow in self-pity and misery.

After drinking his tea, he washed his cup and saucer, emptied the teapot and swilled it out, watching intently as the tea leaves swirled in rotation around the plughole, mimicking the deathly spiral that had so nearly killed him, and he pondered on the quirk of fate that had guided that mortally crippled plane to avoid those killer trees—the second time that he had been shot down during the Battle of Britain in the late summer of 1940.

If fate did intervene, what did fate now require of him? He did not know; fate had not been so very kind to him since.

CHAPTERONE

DI Yarrow lived in a stone-built, bow-fronted Victorian semi-detached house in Carling Green, to the west side of West Garside on the upper slopes of Monksbane Hills, the rolling bank of hills stepping up from the River Gar around which West Garside had grown and expanded.

Nobody seemed to know why the town was called West Garside when there was no North or East or South Garside, but ever since the founding of the town in the mid-18th century as an offshoot of Sheffield’s steel and cutlery business, it had been called West Garside.

The hills continued westwards through a series of valleys and ridges before rising up into the Pennines themselves, the stretching vistas of heather-clad moorland and deep, shrouded valleys with villages untouched by time since before the war—a harsh country of rugged farms and equally rugged farmers—whilst to the northeast, coal mines provided another major source of employment.

To the side of Yarrow’s house stood a lean-to wooden garage in need of painting, and every morning when he came to get into his car, Yarrow told himself he would do the painting on his next free weekend. But somehow that never seemed to happen, and Yarrow knew that, since the death of his beloved wife Marie-Hélène, he had allowed the house to deteriorate.

The garden was unkempt and overrun with weeds, and although he cut the lawns when the grass got too long, the rose beds, once his wife’s pride and joy, had not been pruned or weeded. He chided himself, as he did every morning, for allowing her memory to be diminished by his apathy.

‘This weekend for sure, Marie-Hélène,’ he promised. ‘For sure.’

By contrast, his car—a creamy white 4-door 2.5-litre 1952 Riley RME saloon—was immaculate. He regularly washed and polished the bodywork, the chrome bumpers, door handles, headlight and side lights all glinting and sparkling in the sharp morning light. The interior leather of the seats was redolent with the tang of lemon-scented leather polish, the burred walnut dashboard wax-polished to a mirror gleam, and he knew that the time he lavished on his car was at the expense of his house and garden.

He slowly backed out of his garage and drove down the hill towards the town centre and Endeavour House, the home of West Garside police and CID.

Parking the Riley in the yard behind the red brick police station—a building so ugly that someone had once remarked that a brick shithouse would look prettier. Constructed in 1928, it was a brick and stone purpose-built police station on four storeys and a basement with cast-iron columns and beams, small casement windows, slow elevators, poor ventilation and insufficient toilet facilities—facilities which always smelled of sewage, no matter how often the cleaners put bleach down the sinks and urinals.

Almost as soon as it was built, it had proved inadequate for purpose, with cramped quarters, limited parking and insufficient storage for the mountain of paperwork that a police investigation generates.

As Yarrow walked into the station, he stopped by the front desk to have a chat with the duty sergeant, Dave Armitage, whom Yarrow had known for many years. When Yarrow had first joined the force, it had been Armitage who had looked out for him, as he did all new green coppers. Armitage brought Yarrow up to date on the night’s events, although there was nothing of any great consequence, and then he turned away to answer the telephone as Yarrow made his way upstairs to the CID department.

It was 7.35 in the morning. As usual, he was the first in. He did not sleep well and had been awake since long before dawn, disturbed as usual by the ferocity of his nightmare. Because his sleep pattern was so regularly broken, he had got into the habit of getting to work early, finding that the half hour or so before the other officers arrived helped clear his mind for the business of the day.

Christopher Yarrow, aged 36—the widower and partially blinded ex–Battle of Britain fighter pilot and now Detective Inspector with the West Yorkshire Constabulary—was of medium height and build, with rugged good looks. Looks seemingly enhanced by the web of faint white scars around his damaged eye, and more than one female admirer had remarked that he looked a lot like Richard Todd, the popular film actor best known for his role as Robin Hood in the 1952 film The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men. And like Todd, Christopher Yarrow had also been born in India, the son of a missionary in Peshawar, in the north-west of India, now in the recently created country of Pakistan.

But despite attention from several women—mainly widows—Yarrow remained faithful to the memory of his beloved wife Marie-Hélène.

CHAPTERTWO

1940

The first time he had been shot down, he had been lucky.

He had just shot down a Dornier Do17 ‘Flying Pencil’ bomber (so called because of its long, sleek and narrow airframe) when the Me 109 came out of the sun and shot away large pieces of his tailplane. ‘Green 2 baling out!’ he called through the RT, then undid his harness and disconnected the RT and his oxygen mask.

The canopy slid back easily and, flipping the Hurricane onto its back, he fell out of the cockpit without difficulty, his parachute opening in a bloom of white silk above him. The Me 109 came round again and Yarrow thought the German was going to machine-gun him as he swung helplessly in his parachute—it was not unknown for pilots to be shot in that way. Alan Bird had died like this, and Polish pilots in the RAF routinely shot at German pilots dangling in their parachutes or flew so close above the parachute that the canopy would collapse from the backwash, sending the pilot plummeting to his death.

Polish pilots were even known to strafe German aircrew in dinghies after being brought down in the Channel—retribution for the destruction and dismemberment of their country. But this time, the German pilot merely waggled his wings in acknowledgement of a fellow warrior of the skies and then turned away, fleeing back across the Channel before his fuel ran out.

The fields of Kent spread out before Yarrow like a Turkish carpet: bright greens and the gold of ripening corn, the red clay roof tiles of a village, a silver curl of a sunlight-reflected river, a stand of dark green trees swaying lightly in the summer breeze, cows stolidly chewing their cud, the grey-blue haze of the Channel dotted with ships away in the distance, and above, a criss-cross pattern of contrails from the aerial battles shivered against the brilliant azure sky.

He landed safely in a turnip field but was immediately surrounded by farmers with pitchforks and scythes, thinking that he might be a German agent dressed in RAF uniform. Foolishly, he had scrambled without his wallet and identity card and, unable to convince the farmers that he was English, had been marched away to the nearest police station—luckier than at least one pilot he knew of who had been stabbed to death by farmers with pitchforks under suspicion of being a spy.

Still unable to convince anyone that he was an English pilot rather than a German spy, he was put in a cell with four Germans. They were the crew of a Dornier Do17 bomber, quite possibly the one that Yarrow had just shot down—the second kill to his name. He gave his squadron telephone number to the duty sergeant, asking him to contact the airfield to verify his story and expected to be freed as soon as somebody arrived to pick him up.

The Germans were friendly enough. One of them, Franz the bomb-aimer, spoke good English, and they bore him no animosity for possibly shooting them down. They had not been injured and had been able to safely bail out well before the bomber crashed to the ground in flames.

They were, they told him candidly, attached to Luftflotte 2, I Gruppe, stationed in Cormeilles-en-Vexin, just across the Channel in the Pas-de-Calais area. However, despite the open friendliness of the Germans, Yarrow was far less forthcoming about his own squadron and airfield, making no mention that he flew with 249 Squadron out of Boscombe Down airfield in Wiltshire, not far from Stonehenge.

The five airmen, four German and one Englishman, shared cigarettes, swapped names, and Werner the pilot—slightly older than the others—showed Yarrow photographs of his wife, a dumpy, dough-faced woman staring wide-eyed into the camera, and two surprisingly beautiful daughters dressed in Hitler Youth uniforms, their long blonde hair in plaits, open faces shining in fervent adoration of the Führer.

The Germans were philosophical about their impending incarceration in a British prisoner of war camp, eagerly telling Yarrow that it was only a matter of time before Germany invaded England and they would be released.

Strange, he thought, the Germans have no difficulty in believing me to be English, but I can’t persuade my own people that I am.

‘Spitfire pilot, ja?’ asked Franz as they shared cigarettes.

‘No, Hurricane.’

‘Hurricane! Nein, nein.’ There was a heated discussion amongst the German aircrew before Franz turned back to Yarrow. ‘For us to be shot down by Spitfire, sehr gut, very good. Hurricane, no, not so good. Big shame,’ but this was said with a smile on his face, and Werner went on to explain that among German fighter pilots—not bomber pilots—it was considered somewhat shameful to be shot down by a Hurricane.

Yarrow tried to explain that he had flown both Spitfires and Hurricanes and found the Hurricane the better fighter of the two—not quite so fast or so tight in the turn, but a very stable gun platform, able to absorb considerable punishment.

It was more than two hours later when the cell door opened and the Adjutant, Sq. Ldr Willoughby, peered in. He took one look at Yarrow and shook his head. ‘No!’ he said, ‘I never saw this man before,’ and the door slammed shut again.

‘Sir, it’s me—Pilot Officer Yarrow, Christopher Yarrow,’ he shouted, but to no avail. The cell door remained resolutely closed, solid and unyielding.

The Germans thought it highly amusing. ‘Now you are one of us,’ Franz, the English speaker, chortled. ‘You come with us to prison camp. We make you German pilot.’

Another hour went by before the door opened again and the Adjutant beckoned Yarrow out. ‘Next time,’ he admonished as they got into his MG to drive back to the squadron airfield, ‘make sure you carry your Identity Card.’

CHAPTERTHREE

1954

Taking a cup of tea from the station canteen to his office, Yarrow began to read through the files on his desk. He had sorted them into two piles: New Inquiries and Inquiries Proceeding. Investigations Completed files were sent down to Archives in the basement—a realm guarded by a troglodyte called Sergeant Maurice Capstone, of whom it was rumoured had rarely, if ever, left the archives since his appointment as Archives Officer seventeen years ago, and had certainly never ever been seen outside Endeavour House in daylight.

However, Maurice Capstone had an encyclopaedic knowledge of just about every single case file amongst the hundreds that had been deposited there over the years—case files that filled the endless yards of dusty shelving that lined the walls and down the narrow aisles of the archives section. Ask for a file for a crime committed fifteen years ago and, after a moment’s contemplation, Capstone would raise his ponderous bulk and, counting off the rows on pudgy fingers, would make straight for the file in question.

Not that there was ever much serious crime. Garside was generally a quiet town, relatively crime-free compared to its big sister Sheffield, 16 miles away on the A629.

Yarrow read a file picked out from amongst the New Inquiries pile.

The file concerned an allegation of assault—a Marjorie Forrester had accused an ex-boyfriend of assaulting her during an argument outside a pub.

‘Marcus,’ he called to DS Marcus Harding, recently promoted following the retirement of one of the senior detectives, DS Arthur Millward. He passed the flimsy file to him.

‘Go and interview these two—Marjorie Forrester and Norman Craig—and sort out the truth of the matter. My feeling is that she’s aggrieved over the break-up of their relationship and is looking for some cheap revenge. If so, read her the riot act, let her know she is lucky not to be charged. OK?’

‘Yes, sir.’

Yarrow then read the file on an alleged theft of jewellery by a cleaner from the house of her employer. The cleaner, Adelaide Milburn, had been accused of stealing a pair of diamond stud earrings from the home of Mrs Christina Wallace—an accusation she strenuously denied.

Not without some misgivings, he assigned the case to DC Harry Rawlings. He did not think that Rawlings would handle the issue with sensitivity, but he had little option, being short-handed after Arthur Millward’s retirement. Rawlings, he knew, was bitter and angry, resentful that he had been passed over for promotion, but Yarrow hoped that the passage of time would mollify Harry Rawlings somewhat and make him work that much harder to achieve promotion when the next vacancy arose.

But no. DC Harry Rawlings still seethed with anger—permanently in a fuming rage of resentment and umbrage. Furious. Knotted up so tight with bitterness, anger, frustration and resentment that he could barely bring himself to even speak to Marcus Harding.

Even though it was almost three months since he had been passed over, Rawlings still held deep-rooted resentment against Harding. That resentment had grown and gathered strength like an oncoming storm rather than abating. He, Harry Rawlings, should have been made up to DS rather than Harding. He had more years in the job than Harding, had made more arrests than Harding, and knew more about local villains than Harding ever would. Harding. Still wet behind the ears and he wasn’t even English.

OK, he might have British nationality because his Nazi mother managed to hook up and snare an English guy, but that doesn’t make him British and never will. No fucking way. He’s German, for God’s sake. A Nazi. He even looked like a Nazi—tall and blond, he was the double of Reinhard Heydrich, author of the Final Solution.

In fact, Marcus had lived in England for almost eighteen years. His natural father, Heinrich Müller, had been the editor of an anti-Nazi newspaper in Munich. One day in 1936, he had been beaten almost to death by a gang of Nazi brownshirts and later imprisoned in Dachau concentration camp, where he had died from typhus.

His wife Magda and her two children, Marcus and Magdalena, had fled to England in 1937, Magda eventually marrying Paul Harding, a roofing tiler, who adopted and raised both children as his own.

Marcus loved his stepfather unreservedly, could barely remember his own natural father, and considered himself as English as anyone. Not a Yorkshireman, of course—nobody born outside the County borders could ever be accepted as a Yorkshireman—but he was English and spoke English without a hint of a German accent. He was not German, and most certainly not a Nazi—the Nazis had murdered his father, so how could he ever be considered a Nazi?

Ironically, during his National Service he had been posted to Germany and, as his mother had insisted on him speaking German as well as English, he had been seconded to Military Intelligence, helping process suspected Nazi war criminals.

After completing his service, he joined the police force, having never wanted to do anything else.

His promotion to DS at age 25 had come as a surprise to him. He had always assumed that Harry Rawlings, 34, who had more years in, would get promotion first. But when DS Arthur Millward had retired to grow prize leeks, DI Yarrow had put Marcus up for the job and station chief, Superintendent Trevor Bullock, had agreed.

Yarrow had seen too much of the Harry Rawlings style of policing—learned from his mentor, a DCI called Terry Mason, who was, in Yarrow’s view, the very worst type of policeman. Mason was arrogant, sarcastic, bullying and condescending to his subordinates, but creepily obsequious and fawning to his superiors, lazy and slipshod at his job; preferring to cut corners rather than do the legwork.

Yarrow was sure, but could not prove, that innocent men had gone down because Mason planted evidence or perjured himself in order to obtain a conviction, and he could see that Harry Rawlings was headed down the same path.

Marcus Harding had tried to placate Rawlings after the promotion, but he had seethed in anger from the day he had been overlooked, and nothing that Marcus Harding could say to him could overcome that furious, boiling sense of outrage and resentment.

‘Look, Harry,’ Marcus had said, ‘I didn’t ask for this promotion. OK, I’ve sat the Sergeants exam the same as you, and you should likely have got it before me, I know—but there it is. We’ve just got to get on with it and move on.’

‘Fuck off, Sergeant,’ and with that, Rawlings gave a Nazi salute, shouted ‘Sieg Heil’ and stomped off, refusing to speak to Marcus (whom he called Mucus behind his back) unless it was strictly necessary.

Yarrow could see all of this, and Rawlings’s sullen, stubborn anger and childish petulance only proved to Yarrow that he had made the right decision in strongly recommending Marcus for the vacant DS slot over Rawlings. Harry Rawlings would just have to live with it or put in a request to be transferred to Sheffield, where promotion opportunities might be greater.

Yarrow worked through the rest of the paperwork—the bane of every copper’s life—sending most of the routine cases downstairs for uniform to handle.

CHAPTERFOUR

1940

The next time!

The squadron had been scrambled to intercept a large force of bombers and escorts heading for the airfields of Kent and Essex, and he was closing in on the Heinkel 111 bomber. He knew the Me 109 fighters were high above, but he ignored that. His job, and that of the rest of his squadron, was to shoot down the bombers making such devastating attacks on the fighter airfields. If the bombers got through and damaged the airfields beyond repair, the war was lost. Let the Glory Boys in the Spitfires take care of the German fighters.

He closed in on the Heinkel, watching as the target grew larger in his gunsights.

Green One, David Clarke, the section leader, was ahead to his right tracking another bomber, part of a massive fleet of over 200 Heinkels and Dorniers from all of the Luftflotte 2 Staffels, escorted by several Jasta of Messerschmitt 109s. The third pilot in B Flight, Edward Morrisey, the Tail-End Charlie, was behind to the left. The other planes from the squadron were lost to sight amongst the confused melee of fighters and bombers, and from the corner of his eye he saw a Dornier going down in flames, followed down by a spiralling, smoking Hurricane—but not from 249 Squadron.

He lowered his seat as far as possible to reduce his profile and give him more protection. Switch on the guns, then the Aldis gunsight, fixing the calibration for a Heinkel 111 so that when the target filled the sight, wing to black-crossed wing, the range was right—three hundred yards. The Hurricane juddered as he fired, and he noted the check in airspeed as the sun-bright yellow tracer from the eight wing-mounted Browning machine guns streaked across the airspace like an electrified hose, and bits of the Heinkel began to fly away. He closed in, all eight guns firing straight into the circle of his gunsight, wanting to bring the range down to two hundred yards. He aimed for the wing root of the bomber—weaken the root sufficiently and the wing would fold in, bringing the bomber down.

The next time!

‘Break, break, break,’ he heard Morrisey shouting through his headset. ‘Chris, 109 on your tail. Break!’

Immediately he spun away, diving to the right, but the Me 109 followed him down in a tighter turn. A loud bang—the plane shuddered as each bullet from the Messerschmitt struck, and the crippled plane spun away into the death-spiral. The canopy had shattered in the attack, and he felt the shards of acrylic striking his face, blood streaming down, sharp needles of pain where broken glass from his smashed goggles pierced his left eye.

He fought the spiral, retarding the engine to idle since the power of the engine only increased the speed of the spiral. He neutralised the ailerons and, despite the agony in his wounded leg and hand, brought the plane out of the spin by applying full rudder opposite to the rotation. But he could not control the crippled plane as it ploughed into the coppice, narrowly avoiding a fatal direct impact into the trees but smashing into the ground between the age-old trunks. By good fortune, the plane did not catch fire—had it done so, he would have been incinerated where he sat, unable to move, his legs broken in the impact. He passed out.

Pain. Intense pain, memories of pain, vague memories of being lifted from the wreck of his plane. Blackness.

CHAPTERFIVE

‘It’s as you suspected, sir,’ Marcus Harding said, consulting his pocketbook.

‘Marjorie Forrester did make up the whole story to get back at Norman Craig. She claimed he slapped her face and punched her in the stomach whilst they were arguing outside the “Hammer and Tongs” on Oakbrook Road. Quite an appropriate location, really, because according to witnesses, the two were going at it like hammer and tongs, but nobody saw any punches thrown—lots of yelling and swearing, but no fisticuffs.

‘Seems that Marjorie saw Norman with Helen Dudley, and even though Norman and Marjorie broke up a couple of weeks ago, she was still angry with him for leaving her. Presumably to be with his new woman.

‘As you instructed, sir, I did read her the riot act, making sure she understood the seriousness of a false accusation of assault. She apologised but said she was so angry when she saw them together that she just lost it. Norman’s OK with it all—he does not want her charged, and it’s all water under the bridge as far as he’s concerned. A storm in the proverbial, kiss and make up—well, not that they’ve made up, exactly.’

‘Good, thank you, Marcus. Good job.’

‘Thank you, Guv, but it wasn’t too hard to sort out.’

‘Nevertheless, good job.’

DC Harry Rawlings looked on furiously as he overheard Yarrow’s praise through the open office door. ‘I’ll show Yarrow what a good job looks like—better than that pissing tiddly job Mucus has just done, anyway.’

CHAPTERSIX

1940

Pilot Officer Christopher Yarrow spent many months in hospital recovering from his injuries. Both legs were so severely broken below the knee that surgeons considered amputation, but as a final resort before that drastic step, both legs were placed in a Thomas splint, elevated and then put in traction before the plaster casts could be applied.

He had also broken several ribs, which fortunately did not puncture his lungs, but made breathing extremely painful for several weeks.

Additionally, he broke three fingers and his left wrist.

The wound to his left leg proved not to be as serious as first feared—the bullet had passed through his calf but did not hit either the tibia or fibula. The wound therefore healed without complication, leaving only a bullet-sized scar. The wound to his left hand also healed, but there was damage to some of the nerves, and he never recovered full feeling in the hand.

The most serious injury proved to be that to his left eye. The sliver of glass from his broken goggles, probably smashed by a piece of metal from the shattered canopy, had entered his eye in the lower quadrant and sliced deep across his retina at the rear of his eyeball, shredding it virtually in two.

The eyeball had filled with blood, making it impossible to remove the sliver until the blood had been reabsorbed into his optical bloodstream—a process that took several months. Until the blood was absorbed and the eyeball had cleared, surgeons could not properly examine the eye and remove any glass fragments. Once the initial bandages had been removed from his face, all that Yarrow could see through the damaged eye was a brilliant orange and black kaleidoscope, like a fluorescent tiger, shimmering with the change in light—brilliant in bright daylight, a dull receding grey at night.

When the blood did eventually clear, and an eye surgeon could at last see into the eyeball and remove the glass sliver, it was apparent that nothing could be done to save the sight. From the day of the crash in his Hurricane, PO Yarrow had been permanently blind in his left eye.

When his broken legs had sufficiently healed, albeit still in plaster, Yarrow was transferred to Bellington Hall, some four miles from West Garside, there to continue his extensive recuperation.

The hall was the former residence of the Bellington family, who had made their fortune from the manufacture of sweets and chocolate. Sir Howard Bellington had turned the property over to the Government for the duration of the war for use as they thought fit, and moved into his apartment in Belgrave Square in London and took an advisory position with the Ministry of Food. (After the war, to avoid crippling Death Duties, Sir Howard donated Bellington Hall to the National Trust.)

Initially used as a training base for local regiments, Bellington Hall was now a hospital for recuperating wounded airmen. Most of the wounded men would return to active service, although there were those so severely injured that they could never return to active duties. It was here, whilst waiting for the blood to clear from his punctured eyeball and for his legs to regain their full strength, that Christopher Yarrow met Marie-Hélène Fayolle, an orthopaedic nurse at the hospital.

Marie-Hélène had fled from France just days before the invading German army entered Paris, where her family had lived for generations. With German forces drawing ever closer, her family decided that, apart from Madame Fayolle—Marie-Hélène’s mother—who elected to remain in Paris to care for elderly and infirm parents, they would try to escape to England.

Even though non-participating and only partly Jewish, they had few illusions as to Nazi attitudes towards those with Jewish blood, seeing all too clearly the foul wind of anti-Semitism blowing ever stronger across Hitler’s Germany.

However, in their worst nightmares they could never have imagined that those family members who remained behind—parents and grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins—would all perish in the gas chambers of Auschwitz or Treblinka. Or that their arrest and deportation to the death camps would be assisted by their former neighbours, wartime France being almost as anti-Semitic as Germany.

Marie-Hélène, with her lawyer father and two brothers, had driven their Citroën Traction Avant, firstly to Rouen and then onwards to the Channel Coast, the entire route filled with laden refugees fleeing the German onslaught. Cars, lorries, horse-drawn carts, bicycles, wheelbarrows, prams—an endless procession of fleeing, fearful humanity which, together with scattered units of the British BEF, straggled along the road, all fleeing the Nazi terror.

The fearful columns were frequently strafed by Me 109s and Stuka dive bombers, leaving a harrowing trail of dead and dying. Just beyond Rouen, they came across two young children—a boy of about five or six, and a girl of three—crying and wailing beside the bodies of their parents and an older sibling killed in one of the strafing raids. Fleeing families and troops had passed them by, too concerned with reaching their own safety to give any thought to rescuing two orphaned children standing by the roadside.

‘Oh, Papa, those poor, poor children—we cannot leave them here, leave them to the mercies of the Nazis,’ Marie-Hélène said angrily, sweeping an arm around to take in the death and destruction all about them; bodies, smoking cars and lorries, dead horses, and an overturned pram with a child’s doll alongside it. Wanton destruction and death for no other reason than that the marauding Germans could do so.

‘Papa, we must take them with us—in England they will be safe. Who knows what would happen to them if left here?’

‘We have very little room, Marie-Hélène. We are already four, and our luggage,’ her father protested mildly, torn by the obvious need to care for the children but concerned with practicalities.

‘They can have my seat—I shall walk,’ Marie-Hélène said stubbornly, comforting the youngest child in her arms. ‘Papa, we must, must take them.’ Her brothers joined in, further reinforcing her pleas to rescue the sobbing children, afraid, uncomprehending and so very vulnerable.

‘Very well, we shall take them. We’ll manage somehow.’

‘They are only small, will not take up much room, or they can sit on our knees.’

And so it was settled. The children, still dazed and in deep shock, meekly allowed Marie-Hélène to lead them to the Citroën, and with barely a backward glance, they climbed into the rear seat.

‘Will Maman and Papa meet us later?’ the boy, called Henri, asked, whilst the girl, Josette, curled up on Marie-Hélène’s lap and, sucking her thumb, slept in the blissful ignorance and innocence of childish dreams.

After enduring another strafing raid, they eventually reached Le Havre. There they abandoned the car and purchased their passage from a grizzled fisherman who made more money in a week ferrying refugees across the Channel than he had made in a lifetime of fishing. He landed them at Newhaven on 14 June 1940, with the great mass of Beachy Head their first sighting of England and freedom, leaving Le Havre in smoking ruins behind them—the day that German troops marched into Paris.

After initial internment, interrogation and screening to ensure that they were not planted German spies, the Fayolle family were allowed into the community, whilst Henri and Josette were taken into care. Josette clung in tears to Marie-Hélène’s skirts, sobbing and sobbing as Marie-Hélène, also in tears, handed them over to the authorities.

‘At least now, they are safe,’ her father comforted her.

‘I know, Papa, but what is to become of them? Poor Josette is heartbroken.’

‘I wish I could say, but they will be well taken care of, you can be sure of that.’

(Henri and Josette spent several weeks in an orphanage for refugee Jewish children before he was able to convince authorities that they were not Jews, but Catholics. They were later adopted by a childless French couple and, in 1947, the family emigrated to Montreal in Canada. Beyond that, no further information is available.)

Marie-Hélène Fayolle had trained in orthopaedic nursing at the famous Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital in Paris, and as soon as she was able, contacted the Ministry of Health and offered her services. She was given a trial in St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London, where her expertise in treating patients with severely broken bones was recognised, and she was transferred to Bellington Hall to assist in the recovery of injured airmen, and where she met and nursed Pilot Officer Christopher Yarrow.

As well as supervising the recovery of strength to his legs, she encouraged and helped him to come to terms with his partial blindness. Their developing closeness grew into love, and in April 1942 they were married, their marriage held in the private chapel of the Bellington estate.

CHAPTERSEVEN

1954

Adelaide Milburn looked up nervously as DC Rawlings andPC Pink entered the interview room. Rawlings had interviewed Adelaide the day before and had now arrested her on suspicion of theft from the house of her employer.

She was very fearful and apprehensive. When Rawlings had questioned her at home, he had shouted and bullied her, accusing her of stealing from Mrs Wallace whilst she was cleaning there. He had refused to accept her protestations of innocence, shouting, ‘You people, all thieves, all of you, you only come over here to take our jobs and steal when you can.’

For Adelaide Milburn was from Antigua in the West Indies and had migrated to England with her husband and children, arriving on the MV Empire Windrush at Tilbury Docks on 22 June 1948.

Her husband, Maynard, had fought with the Eighth Army in North Africa during the war. He had been briefly stationed at Catterick Barracks in North Yorkshire, where he had been welcomed and made to feel accepted. After demobilisation, he returned to the West Indies to fetch his wife and family and bring them to England.

They had lived for a while in Leeds before moving to West Garside, where he worked as a mechanic in Jack Purgreaves’ garage, whilst Adelaide worked as a cleaner for various families around the town. She had built up a good, solid reputation for hard work and honesty, and word of mouth from satisfied customers meant that there were always more job offers than she could manage, and so she could afford to be selective.

Which was why the accusation of theft from a house where she worked was so distressing; the years of building up a solid reputation could be destroyed in an instant, and the offers of cleaning jobs could vanish overnight.

Rawlings sat down opposite her and leaned over, his face close to hers. She tried to back away, but PC Eustace Pink (known as Useless Eustace around the station, even to his face), standing behind her, pushed her forwards again. She could smell cigarette smoke on Rawlings’s breath and an underlying reek of old, stale beer. He said nothing for a long, drawn-out minute or two.

‘What are you doing here?’ he suddenly barked in a loud, overbearing manner.

‘You… you brought me here.’

‘Nah, I mean, what’re you doing in this country?’

‘I… we came here to work. To live.’

‘Why, they run out of bananas where you come from?’

Behind her, Adelaide could hear the other policeman snigger.

‘Bananas?’

‘That’s what monkeys eat, isn’t it?’

Useless Eustace sniggered again. He was not especially racist—he had nothing against coons or wogs, as he called them—but he was secretly afraid of the rabid intensity of Rawlings’s rage, not just against the unfortunate West Indian woman, but against the world at large. Useless, within two years of retirement, asked only for a peaceful life without too many headaches, and going with the flow was easier than butting his head against it. Anyway, he was sure the woman had stolen the earrings; no other possibility seemed to exist, and so if a bit of bullying got the result, so be it.

‘Why you calling me a monkey? I’m no monkey,’ Adelaide responded indignantly.

‘You look like a monkey to me. She look like a monkey to you, Useless?’

Pink loomed over Adelaide. ‘Yeah, looks like a monkey to me, Harry.’ He sniffed loudly. ‘Smells like one an’ all.’

‘See, even Useless Eustace thinks you’re a monkey, a little wizened chim–pan–zeeee. Monkey see as monkey do. Monkeys steal stuff all the time. Well-known fact, that, isn’t it, Eus?’

‘Says so right there in the Encyclopaedia Britannica.’

‘See, says so in the Encyclopaedia Britannica—monkeys steal, it says—and you can’t go against what it says in the Britannica. Against the law, that is. Unpatriotic! But then you aren’t English, don’t know the meaning of patriotism.’

‘My husband, Maynard, he fought in the war.’

‘Who for? Hitler?’

‘No, for the British. In the Army.’

‘What in, the Royal Chim-pan-zeees? Been all right fighting the Japs in the jungle then.’

Rawlings was enjoying himself; he had no doubt he would soon force a confession from the woman, get a quick result. That would show Detective Inspector bleeding Yarrow how much of a mistake he had made promoting that fucking Nazi Mucus Harding over him.

He leaned back in his chair to light another cigarette, pointedly blowing the smoke in Adelaide’s face, who turned away, just as Rawlings anticipated.

‘Where’d you hide the earrings, Adelaide?’ he shouted suddenly, causing Adelaide to start back in abrupt panic.

‘Where’d you hide them? They’re not in your house, not in your monkey cage, so where’d you put them? You can’t have sold them already, so you must have hidden them. Where? Where’ve you hid them? Answer me, you black bitch.’

Rawlings was clenching his fists as the latent rage built up, and Eustace Pink began to feel apprehensive. He could go along with a bit of bullying and shouting, a bit of abuse—all part of the game—but physical violence to a woman, that was out of order. But he had no idea how to restrain Rawlings if he got really out of hand.

‘Come on, love, tell us where you hid them earrings, save a lot of bother,’ he said placatingly.

‘I tell you, I told you before, I didn’t take anything from Mrs Wallace’s house. Nothing. No earrings. Nothing.’

‘See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil—that’s what you monkeys do,’ Rawlings shouted, spittle flying from his mouth.

‘Come on, love, be better if you tell us, make it easier, make it easier for the judge to go lightly,’ Pink tried again.

‘I’ll see to it you get deported if you don’t cooperate,’ Rawlings said softly, but with far more menace in his voice than when shouting. ‘You got kids?’

‘What?’ Adelaide responded, confused and very disturbed. How could this happen? She was an honest, church-going, God-fearing woman.

‘You got kids, little baby chimps?’

‘Yes, yes, I have three children. Why?’ she asked fearfully, the nightmare getting worse by the minute.

‘They’ll have to go into care. You get convicted without an admission of guilt; you’ll get deported for sure. You’ll never see them again. Ever! Think on that,’ Rawlings said, thrusting his face once again into hers.

Even Eustace Pink was disturbed now. This was definitely a route he did not want to go down, but he saw the manic gleam in Rawlings’s eye and knew that nothing now could divert Rawlings from this path. But threatening the woman with losing her children was a step too far. Eustace wished he had never agreed to sit in on the interview, but knew in his heart that the reason he had been asked was because he was too readily compliant with bullying and strong-arm tactics. He felt ashamed and weak but knew he would do nothing to ease the poor woman’s anguish.

Adelaide began to cry, softly at first, the tears trickling slowly down her face, and then the dam of her emotions burst, and she began to weep intensely, sobbing loudly into a scrap of lace handkerchief she took from her handbag.

Harry Rawlings leaned back in his chair, a look of smug satisfaction on his face. He had broken the woman, and it would only be a matter of time before she confessed, and the case could be wrapped up.