Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Salt

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

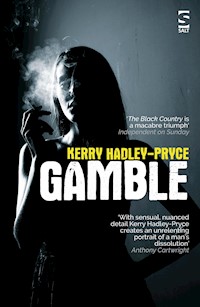

Greg Gamble: he's a teacher, he works hard, he's a husband, a father. He's a good man, or tries to be. But even a good man can face a crisis. Even a good man can face temptation. Even a good man can find himself faced with difficult choices. Greg Gamble: he thinks he can keep his head in the game. He thinks he's trying to be good. Until he realises everyone is flawed. And for Gamble, trying to be good just isn't enough.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 303

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

GAMBLE

by

KERRY HADLEY-PRYCE

SYNOPSIS

Greg Gamble: he’s a teacher, he works hard, he’s a husband, a father. He’s a good man, or tries to be. But even a good man can face a crisis. Even a good man can face temptation. Even a good man can find himself faced with difficult choices.

Greg Gamble: he thinks he can keep his head in the game. He thinks he’s trying to be good. Until he realises everyone is flawed.

And for Gamble, trying to be good just isn’t enough.

PRAISE FOR THIS BOOK

‘You’ll say, after you’ve read it, that you had no sympathy for him at all, for any of them, perhaps, and were not complicit in any way, but you’ll be lying, of course. And it’s that sense of complicity, of being pulled into the intense, claustrophobic disintegration of this selfish man, and the people around him, that makes reading this novel such a vivid experience. I found Greg Gamble’s thoughts sticking to my own like towpath mud. With sensual, nuanced detail Kerry Hadley-Pryce creates an unrelenting portrait of a man’s dissolution into the dark waters of the Stourbridge Canal. Gamble’s unnerving syntax of justification and exoneration – reminiscent in style of Antonio Tabucchi’s Pereira Maintains or Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist – builds on the Black Country edgeland noir of her first novel, with painful psychological honesty and bite.’ —ANTHONY CARTWRIGHT

PRAISE FOR PREVIOUS WORK

‘This is an addictive book that deserves to be up there with the likes of Gone Girl and Girl On The Train it’s as good, if not better, than both. A dark and unsettling read that leaves you feeling like a voyeur of a car crash relationship (where you wouldn’t look away even if you could), I really enjoyed it – 9/10 stars’ —ANDREW ANGEL, Ebookwyrm’s Book Reviews

‘A couple whose uneasy relationship seems as unreliable as that in Gone Girl are driving home, a little the worse for drink, when they accidentally knock someone over, someone they know – but they choose to drive quickly on. The story, and their relationship, becomes increasingly bizarre ...’ —CrimeTime

‘The Black Country is a macabre triumph, whether you read it as a horror fable about love or a meditation on the controlling character of the artist. Either way, this ambitious and memorable first novel loiters like a rotting fish left behind the fridge. I mean this in a good way. The Black Country really is something else.’ —JAMES KIDD, The Independent on Sunday

‘Every so often a novel lands from out of nowhere and grabs you by the eyeballs. Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl was one such, but at least Flynn had some previous form. Kerry Hadley-Pryce’s haunting and unnerving The Black Country is a debut of gothic ambition. The cover hints at David Lynch, and this twisted portrait of a marriage in continual breakdown, of distrust, paranoia and love turned to contempt is a little as though Gone Girl had been reimagined by Lynch.’ —JAMES KIDD, South China Morning Post

‘The Black Country is an excellent book, written in an astonishing voice by a very good writer, and deserves a wide audience.’ —GRAEME SHIMMIN

Gamble

KERRY HADLEY-PRYCE was born in the Black Country. She worked nights in a Wolverhampton petrol station before becoming a secondary school teacher. She wrote her first novel, The Black Country, whilst studying for an MA in Creative Writing at the Manchester Writing School at Manchester Metropolitan University, for which she gained a distinction and was awarded the Michael Schmidt Prize for Outstanding Achievement 2013–14. She is currently a PhD student at the University of Wolverhampton, researching Psychogeography and Black Country Writing. Gamble is her second novel.

Also by Kerry Hadley-Pryce

The Black Country (2015)

§

To him, she’d taste of vanilla, or cucumber, or raw chives, perhaps. She looked like that kind of girl, he thought.

He’ll say he’d watched her arrive, and how the van was parked across his driveway. It would have bothered him before, anyone parking across the driveway; that day though, he’d stood at his living room window (the ‘lounge’, his wife, Carolyn, called it. He hates that word: lounge) and he’d watched her, this girl, through the gap in the mesh of net curtain, and he’d wondered what she’d taste like. He felt a little bit sick – sometimes standing for too long did that to him – but he was trying to ignore all that, and anyway, it was Monday, and he’ll say he always felt the cloy of nerves at the start of another week of teaching. So, watching the girl was taking his mind off all that. Words like ‘willowy’, ‘asymmetrical’ and ‘seemly’ mixed with ‘uncareful’, ‘wild’ and ‘brash’ in his mind as he watched her. Her hair, he noticed, was almost blonde – some bits of it were rapeseedy, he decided – and she seemed to have a habit of pushing stray strands behind her ear. She did that a lot, he noticed. He counted. Fourteen times. There seemed a regularity to her way of doing it, and it reminded him of poetry, the way she kept repeating it. She was carrying cardboard boxes into the building opposite and, as he stood watching her, he came to realise he’d never really noticed it, that building. It was a building, and it was just there opposite his 1950s semi. Looking back now, he questions all that. But he was noticing the girl, just then. She wore, he thought, very red lipstick, and that made her look odd, or the lips look odd, like she had a permanent pout, or had been punched, and he found he was forming an opinion about that. He watched her enter the building and then reappear, and became aware that, with every appearance of her, he’d suck in his stomach, straighten his back. Becoming aware of it made him feel somehow ineligible and a little despairing. He’ll say he realised then, he needed someone to talk to. Just to talk.

He’d taken to sighing a lot. His wife had mentioned it, picked him up on it, so had his daughter. The two of them had begun, he thought, to behave like a coterie. There had begun to be times where one had finished the other’s sentence, or so it had seemed to him. Depressing really. He tried not to think about that, watching this girl. Instead, he tried to guess her age. What would she be? Early twenties? She had enough graceless harmony. Set against the size of the building, she appeared, to him, to enhance the space somehow. The geometry of it made her, or it, look unreal. He’ll say she seemed to make the building seem experimental, with absurd angles. Morning shadows, he thought, had created all sorts of distortions. They made the building look very high, for a start, he thought, and made bits of the brickwork glitter like there were sequins, or little pearls, somewhere there. He’d started thinking like this again, thinking poetically. Sometimes, he’ll say, he thought it was eating him alive, the poetry. He’d lost touch with his Music Club pals a couple of years back, he’d heard on the grapevine that a couple of them had died of cancer, but he’d started thinking about maybe writing some songs, some lyrics.

In the shower that morning, he’d looked at the muscles of his arm, his biceps, which he could still flex if he clenched his fist. He’d thought that wasn’t bad for a fifty-two year old. He’ll tell how he removed the plaster a nurse at the hospital had put on the vein in the crook of his arm, had looked at the little rash it had left behind, had thought he must have been allergic. And he’d watched it, the plaster, spiral away down the drain, he’ll say he’d wondered if it might eventually cause some sort of blockage he’d have to deal with. He’ll say he wanted to cup his hand around his balls, to check, re-check, re-examine, but the thought of doing that made him dizzy, sick. He’d thought, briefly, about the terms ‘bloods’ and ‘biceps’. He’d thought they were odd plurals, a bit of an error perhaps. Now, looking at this girl, this building, though, he did wonder whether there was error in pretty much everything, but he just hadn’t noticed before.

A voice from the hallway made him jump, and he realised he’d been holding a mug of tea all the time. Cold by then.

He’ll describe how his daughter stood, one hand on her hip. The skirt of her school uniform, he noticed, short, bunched up at the waistband.

‘Isabelle, love,’ he said. ‘That skirt. It’s . . .’

He remembers placing his mug down on the arm of a chair, and making chopping motions on his thigh.

‘Yeh, yeh,’ Isabelle was saying, and she’d begun retreating down the hallway, away from him.

He sighed, thought about moving his mug from the arm of the chair. But it was only a thought. He knew he’d need to move it before he left because he knew, for sure, that Carolyn would be irritated if he didn’t.

When he looked out of the window again, he’ll tell how the girl and the van were gone, and the lighting had changed, he thought, so the building seemed less big, less pristine, more like a Victorian factory – what had it been? A workhouse that backed onto the canal? The water there is dark and flat, as only that water in Stourbridge Canal can be. He’ll say he was thinking, it’s alive though, and that’s something.

And looking out, just then, he’ll say how he realised he could feel it, this building with all that girl’s things in it, bearing down on him, that’s what he’ll say. He let it. He let himself identify with it. He breathed it in. He said, or seemed hear himself say, ‘Yes.’ In the distance, he could hear his daughter’s voice saying something about being late, getting into trouble. He felt for his keys in his trouser pocket, his cigarettes, lighter, small change. And he’ll say he felt what had become by that time a dull ache, a thump of a pain in his groin. He’ll tell how he knew then he’d need someone to talk to at least. He sighed, said, ‘I’m there now.’

On his way out, he picked up the pile of exercise books – his weekend marking – from the bookcase in the hall. He’ll say how he looked briefly at the way his year nines had written his name: ‘Gamble’. Not even ‘Mr. Gamble.’ He’d sighed, again – he remembers doing it.

The car started on the second go, and he’d turned left onto the dual carriageway, he’ll say, before he’d remembered leaving the mug of cold tea on the arm of the chair.

The canal contains lots of things. Things from the past that have sunk right to the bottom and are embedded in the silt and soil and mud, if that’s what it is; things that linger in the dark water, suspended, perhaps. Stuck. And the water is greasy with things from the present: oil from Black Country factories, long tall tin cans, cigarette ends, reflections of trees in the shape of people and people’s faces. Weeds grow in the canal, yet when they reach the surface, when they appear, when they break through, their death is quick, and their hardened brownish stems poke up and remain still. Only the horizontal image of them moves on the surface of the water, and that only slightly. It’s like the air has petrified them, or the water has, and what they could have been has been stolen away.

That day, there’d been a smell. Not the urban smell of dust and smoke. Not the grit and fumes from the ring road. Not just that smell. But a smell of something acidic. No. Not acidic. Something sharp, like pear-drops, maybe. Pear-drops and metal and bone and blood. And sap. The smell that sap makes when it’s bleeding from a branch. That sticky, piny smell. As well. Even the rain hadn’t washed that smell away.

And there’d been clicks, like the sound of knuckles cracking. Clicks and pops. Childish sounds. Like the sounds you might expect ivy to make, or a twisting vine might make as it grows and burrows its way into walls and round trees; like a tree might make as its branches flex against a weight, maybe; as the bark of the branch of that tree might make as it gives way a little, as it separates from the flesh of the branch, as it squeaks as it bends. Maybe. There were no leaves to rustle, just yet, not on this tree or that day. But had there been, they would have been of the smallish, darkish variety, soon polluted with rain and with dust on the underside.

That day, there’d been an echo of a breath from somewhere, a feel of hair falling across a face and of skin stretching to a break – a tear. There’d been a mouth, open and wordless, and something valuable, lost. And hands with fingers uncurled and heavy.

The school was full of the vocal fry of the young, or immature, or stupid, he’ll say. The corridors echoed with it, the stupidity. Gamble was always struck by that. Isabelle was right, they were late. She’d rushed off to class, and Gamble had speculated about how that had changed between them, that rushing off she did. Gone, it seemed, were the days when she’d hug him and tell him to have a good day. The car journey, he noted, was now silent, except for the scratch of noise from her ear-phones. Did she listen to music? He wondered about that. What exactly did she listen to? Their parting had begun to be instant – it had been that morning. He’d barely parked up and she’d been out, as if to avoid the question of even a word. He’d felt a thought begin to run away with him: she’d be doing her GCSEs in the summer, he’d thought. And then what? What then?

Inside the school, as he set foot inside, he felt as if he’d lost his bearings, just slightly. There followed an acute moment of depression, yes, depression, before he realised exactly where he was – what he was – there. Then, he’ll say, he seemed to be suddenly in role, as if the energy that was, essentially, him had begun to leak out, and something else was leaking in. There was all that noise and bother. And stupidity. He’d missed the morning’s staff meeting, again, and seemed to be walking – struggling to walk – against the tide of pupils massing in the corridor. He’ll say he felt his stomach beginning to churn without really knowing why. He looked at the exercise books he was carrying, at the way his fingers curled round them. Without reason, the fingertips didn’t look like his own that day. They looked generically male: square, with the odd hang-nail, a bit dirty. But they didn’t look like his. He felt a swell of absent vision that seemed to be enlarging as he walked, or moved, more like. And he felt himself tilt, and then the feel of the cold of metal on his shoulder. Was he leaning then? He wondered if he was leaning against one of the lockers. He felt his mouth fill with spit, and from somewhere, a voice, adolescently chinking, saying ‘Sir’ and then he was somehow sitting, or being sat, on a plastic chair, the back of which strained when he leaned on it. Something, or some things, fell onto the floor, out of his pocket. He’d felt it happen, but his breath was too short, too thin, to concentrate on anything but himself. Christ, he thought, I’m dying. He’d felt like he was a fish, just beneath the surface of cold water, that’s what everything seemed to look like, too. Christ, he thought. He might even have said it. Carolyn flashed into his mind, as she is now: heavy around the hips, the chin, with that look that used to be earnest, enticing, and now is just grave. He worked his fingertips across his forehead and felt it like a smear of warm grease. And something seemed to be happening in his neck, his throat, particularly: bubbles, flutters that made him want to cough, and he felt like his heartbeat had reached there and was floundering. ‘Jesus,’ he heard himself saying. ‘I’m dying.’

‘You’re not dying,’ a voice all around his head said, and something, what was it? A paper bag? It was shoved over his mouth.

He smelt his own breath, the metal of it. Carolyn’s face retreated, disappointed, as ever, unnatural, black and white, into dead air. He seemed to surface, to come back. And then his mouth was dry. In front of him, when he blinked, when he fluttered back, a collection of interested year eights were being shooed away by the Head Teacher. She seemed to be saying something about getting to lessons, or something about sitting quietly. It was all just a jumble of words to Gamble.

‘I’ll get to my lessons, Miss Henshaw,’ he said, or tried to say, but his tongue was big, dry, like a separate entity.

Miss Henshaw squinted at him. He’ll say he saw, he noticed, because she was so close, that she was wearing mascara and he felt an involuntary moment, a flicker of something like want. Either want, or need. He’ll say there seemed no-one he could talk to then. It was automatic when he placed his hand on his crotch. The little overhang of flesh above his belt seemed hard, at least, but there was that constant, nagging pain just there. Somebody, some child, somewhere, laughed loudly, he was sure he heard that.

‘Go home, Mr. Gamble,’ Miss Henshaw said, and it sounded to him like the beginning of an incantation.

Off and away at the back of a thinning crowd, he spotted Isabelle, and the look on her face, it made him feel liquefied.

Miss Henshaw handed him his lighter, some change. She’d picked them up off the floor, had placed them into the palm of his hand, had closed his fingers round them, as if they must have been precious to him. She said, ‘Go on, Greg. Just go home.’ But, even though he’d wanted to, he heard no kindness in the words.

Gamble didn’t argue about going home. There was, is, a heaviness under his eyes; the students, the job, life; they’ve all done that to him, he thought. His mouth was still dry. He couldn’t work out why he was feeling somehow more diminished, lately. Less happy, for certain. I should try feeling elated, he thought, I should just tell myself that I’m perfectly fine, really.

In the car, he’ll tell how he adjusted the rear-view mirror, caught sight of himself. He’ll say that what he was thinking was written in deep lines on his face. He examined his skin like a forensic exercise, stretching it in places with the tips of his fingers. He thought, I’m getting jowly, and something is happening to my mouth. He was thinking, I look like an animal, not a human. He was wondering where his forties went, whether his fifties would disappear as quickly. And that made him feel intensely sad. He saw within his eyes a collaboration of people – his father, mainly, but Isabelle, too – so the sight of himself in the mirror revolted him. He thought it’s odd how it’s possible to intuit expressions like that, and before starting the engine, he breathed in and out a couple of times, tried to calm, tried to change, literally, but the car smelt of Isabelle’s shower gel or perfume or whatever, and it was distracting, and the longer he sat, the quicker the day outside seemed to end. The low light of it dazzled him. It was like some kind of horrible metaphor. In front of him, when he looked, the school, its flat roof, flat car park, flat notedness, became mottled with spits and spots of rain. He shook his head, as if that would cancel the plummeting sensation he was feeling, and swallowed back the notion that life is very short. The very existence of that thought struck him like a thunderclap, but that did not stop it from developing. He tried to rationalise by telling himself he was nearing the end of a hard term, that it would soon be Christmas. Everyone had continued to panic about Ofsted and data and league tables, and most of his students had yawned their way through pretty much all of his lessons. ‘Bored,’ they’d said, with faces full of spite, unblinking, a terrible confidence about their narrow mouths and eyes.

Christ, he thought. It’s killing me. I really am dying.

In the rear view mirror, he caught sight of his jaw, set tight, as he drove away.

Everything had been still. The weather had washed all colour away. Water in the canal had looked like melted wax – like a picture, a photograph. A figure, slim, wearing trousers – jeans, perhaps, a heavy jacket, had stood looking at the water. The reflection, exact, not distorted. The hand, the forefinger of the hand, horizontally across the mouth, the lips. The elbow, held, cupped, by the other hand, tucked right into the body. And down, the feet – smallish – in boots, had made temporary imprints in the mud of the canal towpath. Behind, factories, Victorian – rolling mills, steel stockholders – long-since closed – had stared out with layers of corrugated, half-rusted tin on roofs separated from tall breezeblock walls in places. Glass from the windows was jagged and grey with wetness. A faded paper sign, small, stuck in places, had offered a ‘warning to the public’, something about authorisation and dangers and trespassing and consequences. And beneath it, and round the corner on a different wall, someone had painted the block outlines of cats, black, standing, sitting, in the process of jumping. Feline silhouettes. Some graffiti by some local art student, most likely. You might say the scene was peaceful. You might. But you’d be wrong.

Across the bridge, in the near distance, a man had walked. Quickly. And as he’d come into view – his head, his neck, his shoulders, his body had come into view – he’d flicked a half-smoked cigarette sideways into the water without looking. And there’d been a hiss. And the figure standing next to the water’s edge had seemed to click into motion like a mechanical doll: moving the hand from the face, straightening the jacket. And the look on the face. How to describe it? A lightening of features, eyes widened, a mouth stretched, skin pinkened. From a distance, it had been hard to say. But the man, when he saw the figure waiting, had quickened his step until . . . until he was almost within touching distance. It had been like he’d given himself an enforced moment of inhalation, like he’d wanted to savour that exact second for whatever reason – sometimes you have to allow yourself to – and he’d seemed to be allowing himself to be momentarily vulnerable, and then that’s when she’d moved to him, and they’d embraced. No, not embraced, exactly. More hands against shoulders, against arms, against elbows. Cheek against cheek against lips against lips. Shadow noises of movement. To begin with. A pelagic zone of touching. Something and nothing. And then a conversation. Short. Painful. And the intensity of light all around had seemed to change then, become bluer, as if the entire supply of oxygen had been, or was being, used up in the few words they’d been speaking. And their voices had carried along the surface of the water. And the water had been like an unsutured wound.

He’ll admit to buying wine instead of painkillers on the way home, from a shop decorated for Christmas. Two bottles. He wasn’t much of a drinker, not really. The girl behind the counter, an ex-pupil, asked for proof of age, as if it was the funniest joke.

‘You have to look twenty-one, sir,’ she said, and her voice was sickly-sweet. ‘Or I’ll lose my job if I serve you.’

Gamble didn’t, quite, recognise her. He’ll say, with good reason, it was more than just an occupational hazard, bumping into ex-students. In some ways, it still makes him feel like a minor celebrity, but that’s Gamble for you. He’ll say he found himself twisting his wedding ring, but looking straight at her. This one, this girl, though, he could tell, would have been a troublesome one. Her hair and nails were blue and she had thick lines of black on her eyelids. In that light, she looked like she was dressed for Halloween. But there was a look in her eyes, he thought, something like adoration, or tease. He instantly fumbled in his bag for his driving licence and then stopped, flushed red from the neck up.

‘Oh,’ he said. ‘I see. It’s a joke.’

He tried to laugh, but it came out like a sneeze. It didn’t stop him feeling a flicker, though, like he was a teenager, or just a bit younger, again and he’d just heard the name of his secret girlfriend. Of course, he’ll say he’s just trying to be honest.

Just before he paid, he asked for cigarettes, and when the girl gave them to him, the tips of their fingers touched, and Gamble wondered. He always wondered. In truth, he was weakened, already, then. The girl, he thought, blushed, and gave him a look. How old is she? he thought. He tried to remember what year she’d have left school, but couldn’t. She’s young, but old enough, she must be, is what he was thinking.

He contemplated asking for something else, the painkillers perhaps, so as to stay there a little longer, but didn’t. When he left the shop, he’s sure he saw her, through a thick reflection in the window, watching him go. He’ll tell how the beginning of a little fantasy involving himself and her flickered into his head. It made him feel daring, sexy, and he’ll say he needed that. He felt like loosening the tie, undoing the top button of his shirt, in front of her. He considered going home, getting changed and returning to the shop, just to see if his instincts were right, just to see what might happen. He couldn’t help it, Gamble couldn’t. He knew he shouldn’t think like that, he just couldn’t help it, despite everything. But as he walked towards his car, his hands full, the bottles gently knocking against each other, the pack of cigarettes held against his chest, he heard first, then saw a van, white. It was the exhaust, something about it, it was rattling, and it made the engine sound, what, he couldn’t find the word, then he did: like a brute approaching, he decided. It made him jump, the suddenness of its approach, and his shoes tapped at the pavement like a clock, ticking, or a bomb. They saw each other at the exact same time, Gamble and the girl in the passenger seat. He recognised her, even in that split second. It was the girl’s red lips. It was something about the redness of the lips, he thought it was, the kind of pout it gave her. He became aware of the familiarity – not familiarity, more the recollection – of the girl’s hair: the colour of rapeseed in places. It was the girl from that morning, the one going in and out of the building. And who was beside her? A thug, by the look of him, Gamble decided, a thug with a baseball cap on sidewards and a grin that wasn’t a grin. Even as quickly as the van passed him by, the girl’s eyes traced the outline of Gamble’s face, or seemed to, then lower, to the pack of cigarettes, the wine he was carrying. The weight of judgment fell like a blade between them, or at least, that was the feeling Gamble had. And it was that feeling that was the decider: he’d drink a bottle of that wine, he thought, maybe both of them, by himself. And anyway, he was just starting to feel the twinge of soreness and slight fever he was getting used to having. Life, he thought, was too short to be disapproved of.

He did not go home. Not straight away. He remembers rain coming fast and heavy, all of a sudden, and the wipers of his car didn’t seem to keep up with it, instead smearing water across his vision. He’d opened a bottle of wine as he drove, pleased with himself that he’d accidently chosen screw-top lids. Carolyn, he thought, would be appalled. She’d have been even more appalled to know he’d swigged at the bottle, almost finished it off, as he drove. It had left that taste of vanilla and cucumber lingering on his tongue. He’d tell you, if you asked, that he wanted to feel plucky, carefree. He’d reduce it to that. It’s more complicated, obviously. He’d been heading out towards Worcestershire – for no other reason than it’s not home – and his head, of course, had become filled with harmonic tension, one sound, one thought, competing with another. Through all of that, he could make out hills in the distance – is it Clee, or Clent? – and there were fragments of lightning, flashing red across the horizon. He could smell the ozone of it, even inside the car, even above the taste of the wine, and that – all of that – seemed to distil into a well of aggressive need. He felt it collecting inside him. Carolyn had always dismissed it, this aspect of him, as his ‘freak-out moment’, and Gamble had always wondered about that, whether it wasn’t simply a tactic, a way of somehow marginalizing him and what he felt. He turned on the radio and fumbled with switches and buttons to find music, but everything he found put different colours in his head and made his chest strain. All it seemed to do was emphasise some emptiness. He had days like this. He’d tell you about them: days when even music – especially music – could not act as a salve or a distraction. Carolyn, he thought, most likely had some theory about that.

He was, momentarily, tempted to drive fast, faster, round the lanes there. For the dare of it. But just the thought seemed to bring on his nervousness, seemed to overlay the fearlessness brought on by the wine. So, he had a tactic he tried to use at moments like this: he tried to take in the ‘moment’. He’d overheard one of the Psychology teachers talking about it in the staff room, taking in the ‘moment’, so he’d tried it, and sometimes it worked, this absorption of the everyday. He tried to take in the feel of the warmth from the heater, the comfort of the seat, the look of the trees, the sound of the rain. He did this and tried to re-calibrate his thoughts by noticing the undulations of the road, and he aligned that with the steady pitch of the engine. The road was thin, little more than a single track in places with a dangerous camber that forced him to hold onto the steering wheel tightly with both hands. Alongside, weather had flattened tall grasses and weeds so that it all looked, to him, just then, defeated. He tried, he really did, to take in the moment, but it was hard and the nervousness, the old anxiety crept back at him. For a fleeting second, he wondered what would happen if he were to close his eyes – how long he could close them for before . . . anything should happen. The thought surprised him, sent a thud through his head, seemed to make him more aware of himself, of the stretch of seatbelt across his chest. It was like he’d woken up from a half-sleep and everything felt like a big surprise, everything looked sharper. And his attention was taken by a field beyond a hedge. The rapeseed flowers had long been cut, but there was still a yellowing that seemed to linger low, and he could see it. And it reminded him of the girl from that morning. Her hair. That brassica yellow. And the slowing raindrops against the windscreen, to him, just then, were like sequins. And thinking of that made him wilt and tense at the same time. And he might remember this next part with more precision than he’d like: he’ll say he changed down a gear because there’s a bend in the road, a left hand one. He heard water, puddles, shlush against the tyres but felt in control, steady. And as he rounded the bend, the grass verge seemed wider, higher. He could see the sandiness of the soil there, made even more jaundiced by the damp, and it made him think of family seaside holidays, ones he and Carolyn and Isabelle had gone on, but only for an instant, because it was then he saw it. It was all in low resolution – wine-soaked, he might think now: a van, white, parked up on the skew on the grass verge, just there. The exhaust, he noticed, hung low, was almost on the floor. And there, standing next to the far hedge away from the road – hawthorn, he thought, the hedge – was a man. He was wearing his baseball cap sidewards this man, and Gamble could make out the existence of an emblem, but not quite what the emblem was on the cap. He could see this man wore a denim jacket, and seemed to be facing the road. He was gesticulating, this man was, jabbing a pointed finger, which made the sleeve of his jacket ride up revealing a line of blue tattooed script – very blue against skin so white it looked palsied. Beside him – no, in front of him, with her back to the road, a girl. The girl, Gamble could tell. He could tell by the hair, he just could. As Gamble passed, he was slowed by the corner and the uncanniness of it, the very fact of the look of the scene forced him to try to interpret what was happening. The man’s hands, he noticed the skin of them, seemed bright white. There might have been a cigarette between the fingers. Maybe not. It was like he was waiting for something, an answer, maybe, not yet due, or impossible to give. The girl raised her head as Gamble passed, and, as the angle of her changed, he saw her eyes, and her lips. It was like he knew her from somewhere – not just from that morning, not exactly, but knew of her, the essence of her. And behind her, that miasma of yellow from the field. He felt something odd in the car, like the beating heart of a frightened child, and heard the bottles of wine, one as good as empty, one full, clink together in the footwell. They didn’t break, but instead rolled around dangerously, seductively. Gamble felt the warning of them. There was a moment, a split second, really, when he braked. It was an automatic action, a co-location of thoughts, and as he did, simultaneously, he saw it happen. He saw the man grabbing the girl. He wasn’t simply grabbing her, this man, he was grabbing at her. Plucking at the air around her, and occasionally catching her, or bits of her clothes or the bare skin of her neck, her face. It was, Gamble thought, as if he was sprinkling something over her. She, meanwhile, stood, rooted, it seemed, but swaying around his touch – a sparring partner, or his property, perhaps. Gamble slowed down, watched it all happening, no, saw