5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

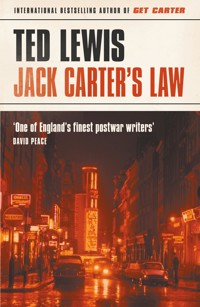

THE NOVEL BEHIND THE CULT FILM STARRING MICHAEL CAINE Doncaster, and Jack Carter is home for a funeral - his brother Frank's. Frank's car was found at the bottom of a cliff, with Frank inside. He was not only dead drunk but dead as well. What could have made sensible Frank down a bottle of whisky and get behind the wheel? For Jack, his death doesn't add up. So he decides to talk to a few people, do some sniffing around. He does, but is soon told to stop. By Gerald and Les, his bosses from the smoke. Not to mention the men who run things in Doncaster, who aren't happy with Jack's little holiday at home. They want him back in London, and fast. Now Frank was a mild man and did as he was told, but Jack's not a bit like that ...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 340

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Get Carter

TED LEWIS

CONTENTS

Get Carter

THURSDAY

The rain rained.

It hadn’t stopped since Euston. Inside the train it was close, the kind of closeness that makes your fingernails dirty even when all you’re doing is sitting there looking out of the blurring windows. Watching the dirty backs of houses scudding along under the half-light clouds. Just sitting and looking and not even fidgeting.

I was the only one in the compartment. My slip-ons were off. My feet were up. Penthouse was dead. I’d killed the Standard twice. I had three nails left. Doncaster was forty minutes off.

I looked along the black mohair to my socks. I flexed a toe. The toenail made a sharp ridge in the wool. I’d have to cut them when I got in. I might be doing a lot of footwork over the weekend.

I wondered if I’d have time to get some fags from the buffet at Doncaster before my connection left.

If it was open at five-to-five on a Thursday afternoon in mid-October.

I lit up anyway.

It was funny that Frank never smoked. Most barmen do. In between doing things. Even one drag to make it seem as if they’re having a break. But Frank never touched them. Not even a Woody just to see what it was like when we were kids down Jackson Street. He’d never wanted to know.

He didn’t drink scotch either.

I picked up the flask from off the Standard and unscrewed the cap and took a pull. The train rocked and a bit of scotch went on my shirt, a biggish spot, just below the collar.

But not as much as had been down the front of the shirt Frank had been wearing when they’d found him. Not nearly so much.

They hadn’t even bothered to be careful; they hadn’t even bothered to be clever.

I screwed the cap on and put the flask back on the seat. Beyond fast rain and dark low clouds thin light appeared for a second as the hurrying sun skirted the rim of a hill. The erratic beam caught the silver flask and illuminated the engraved inscription.

It said: ‘From Gerald and Les to Jack. With much affection on his thirty-eighth birthday.’

Gerald and Les were the blokes I worked for. They looked after me very well because that’s what I did for them. They were in the property business. Investment. Speculation. That kind of thing. You know.

Pity it had to finish. But sooner or later Gerald’d find out about me and Audrey. And when that happened I’d rather be out of the way. Working for Stein. In the sun. With Audrey getting brown all over. And no rain.

Doncaster Station. Gloomy wide windy areas of rails and platforms overhung with concrete and faint neon. Rain noiselessly emphasising the emptiness. The roller front of W. H. Smith’s pulled hard down.

I walked along the enclosed overhead corridor that led to the platform where my connection was waiting. There was nobody else in the corridor. The echoes of my footsteps raced before me. I turned left at a sign that said Platform Four and walked down the steps. The diesel was humming and ready for off. I got in, slammed the door and sat down in a three-seater. I put my holdall down on the seat, stood up, took off my green suede overcoat and draped it over the holdall.

I looked down the carriage. There was about a dozen passengers all with their backs to me. I turned round and looked through into the guard’s van. The guard was reading the paper. I took my flask out and had a quick one. I put the flask back in the holdall and felt for my fags. But I’d already smoked the last one.

At first there’s just the blackness. The rocking of the train, the reflections against the raindrops and the blackness. But if you keep looking beyond the reflections you eventually notice the glow creeping into the sky.

At first it’s slight and you think maybe a haystack or a petrol tanker or something is on fire somewhere over a hill and out of sight. But then you notice that the clouds themselves are reflecting the glow and you know that it must be something bigger. And a little later the train passes through a cutting and curves away towards the town, a small bright concentrated area of light and beyond and around the town you can see the causes of the glow, the half-dozen steelworks stretching to the rim of the semicircular bowl of hills, flames shooting upwards – soft reds pulsing on the insides of melting shops, white heat sparking in blast furnaces – the structures of the works black against the collective glow, all of it looking like a Disney version of the Dawn of Creation. Even when the train enters the short sprawl of backyards and behinds of petrol stations and rows of too-bright street lights, the reflected ribbon of flame still draws your attention up into the sky.

I handed in my ticket and walked through the barrier to the front of the station where the car park was. A few of my fellow passengers got into cars, the rest made for the waiting double-decker bus. Rain drifted idly across the shiny concrete. I looked round for a taxi. Nothing. There was a phone box near the booking office so I got in it, found ‘Taxis’ in the directory and phoned one. They said five minutes. I put the phone down and decided I’d rather have the rain than the smell of old cigarette ends.

Outside I stood and stared across the car park. The bus and the cars had gone. Directly opposite me was the entrance to the car park and beyond that was the road with its loveless lights and its council houses. It all looked as it had looked eight years ago when I’d seen it last. A good place to say goodbye to.

I remembered what Frank’d said to me at our dad’s funeral, the last time I’d seen the place.

I’d been eating an egg sandwich and talking to Mrs Gorton when Frank had limped over and asked me to pop upstairs with him for a minute.

I’d followed him into our old bedroom and he’d taken a letter and he’d said to me, ‘Read it.’ I’d said, ‘Who’s it from?’ He’d said, ‘Read it.’ Still eating the sandwich, I’d looked at the postmark. It had come from Sunderland. The date was four days earlier. I’d taken the letter out of the envelope and I’d flicked it over and looked at the signature.

When I’d seen who it was from, I’d looked at Frank.

‘Read it,’ he’d said.

The cab swung into the car park. It was a modern car with a lit-up sign in the middle of its roof. It stopped in front of me and the driver got out and walked round and opened the passenger door.

‘Mr Carter?’

I walked towards the car and he took my holdall and put it on the back seat.

‘Lovely weather,’ he said.

I got in and he got in.

‘Where was it?’ he said. ‘The George?’

‘That’s right,’ I said.

The car began to move. I felt in my pocket and pulled out my packet of fags but I forgot it was empty. The driver pulled a packet of Weights out of his pocket.

‘Here,’ he said, ‘have one of these.’

‘Thanks,’ I said. I lit us both up.

‘Staying long, are you?’ he asked.

‘Depends.’

‘On business?’

‘Not really.’

He drove on a bit more.

‘Know it round here, do you?’

‘A bit.’

We were driving along the same road we’d been on since the car park. The lights were getting brighter. In front of us was the main street.

It was a strange place. Too big for a town, too small for a city. As a kid it had always struck me that it was like some western boom town. There was just the main street where there was everything you needed and everything else just dribbled off towards the ragged edges of the town. Council houses started immediately behind Woolworths. Victorian terraces butted up to the side of Marks & Spencer’s. The gasworks overshadowed the Kardomah. The swimming baths and the football ground faced each other only yards away from the corporation allotments.

And really it was a boom town. Thirty years ago it had been just another village hiding in the lee of the Wolds. Then they’d found the sandstone. Thirty years later what had been a small village was a big town and would have been bigger if it hadn’t been for the ring of steelworks hemming in the sprawl.

On the surface it was a dead town. The kind of place not to be in on a Sunday afternoon. But it had its levels. Choose a level, present the right credentials and the town was just as good as anywhere, else. Or as bad.

And there was money. And it was spread all over because of the steelworks. Council houses with a father and a mother and a son and a daughter all working. Maybe eighty quid a week coming in. A good place to operate if you were a governor who owned a lot of small-time set-ups. The small-time stuff took the money from the council houses. And there were a lot of council houses. Once I’d scrawled for a betting shop on Priory Hill. Christ, I’d thought, when I’d happened to find out how much they took in a week. Give me a string of those places and you could keep Chelsea. And Kensington. If the overheads were anything like related to what that tight bastard I’d been working for had been paying me.

We pulled up outside The George. It said ‘The George Hotel’, but all it was was a big boozer that did bed and breakfast. It was all snowcemed and the woodwork was painted blue and the windows were fake lattice but I knew inside it was crummy. When I first started going in pubs when I was fifteen, The George was the one boozer I daren’t try. It looked so respectable on the outside. Later I learnt different. I still didn’t go in, but for different reasons. But at this moment it suited all right.

The driver whipped round the front of the car and opened my door. I got out. He opened the back door and got the holdall.

‘How much is that?’ I said.

‘Five bob,’ he said.

‘Here you are,’ I said. I gave him seven and six.

‘Thanks, mate,’ he said. ‘All the best.’

He made to take my bag towards the hotel.

‘That’s all right,’ I said. ‘I can manage.’

He gave me the bag. I began to turn away.

‘Er,’ he said, ‘er, if you’re off to be about during next few days and you need owt, driving anywhere, like, give us a ring. Right?’

I turned to look at him. The blue of the neon and the dead yellow of the high street light made him look as though he needed an oxygen tent. There was an earnest helpful look on his face. Rain looked like sweat on his forehead. I kept looking at him. The earnest helpful look changed.

‘I told you,’ I said. ‘I can manage.’

He looked at the holdall then at me, tracing back my words. He tried to frown, but the little bit of fear made him look more hurt than angry.

‘I was only being helpful,’ he said.

I smiled at him.

‘Goodnight,’ I said, and turned away.

I walked towards the door marked ‘Saloon’ and opened it. I didn’t hear him close his.

Amateurs, I thought. Bloody stinking amateurs. I closed the door behind me.

You had to give the landlord credit. He’d really tried to make it look the kind of place that married couples in their forties would like to come to for the last hour on a Saturday night.

There was that heavy wallpaper in panels, the relief stuff that tried to look as though it was velvet. There was a photo-mural of Capri. There were wall seats in leatherette that looked as though they’d been put in a couple of years ago. There was formica on all the tabletops and also on top of the bar. There was some plastic wrought iron creating a pointless division. There was also a clean shirt on the landlord.

There were a couple of yobbos playing a disc-only fruit machine. There was an old dad with a half-a-bitter and the Racing Green, and sitting next to him there was a very old brass in a trouser suit leaving her lipstick all over a glass of Guinness. But no sign at all of the person I was looking for.

It was quarter past seven.

I walked over to the bar. The landlord was looking at something in the till and thinking. The barman was leaning against the mirror at the back of the bar. He had his arms folded. His hairstyle was Irish Tony Curtis. Farther down the bar was a man of about thirty in a Marks & Spencer cardigan with a lovat green shirt open at the neck. He was sitting on a stool and looking at himself in the mirror.

I put my holdall down and looked at the barman. He didn’t move.

‘Pint of bitter,’ I said.

He let his arms unfold, reached out for a pint mug and made his weary way to the pumps and without putting anything more into it than it needed he began to pull the pint.

‘In a thin glass please,’ I said.

The barman looked at me and the bloke down the bar looked at the barman.

‘Why didn’t you bloody well say?’ said the barman, slowly putting the brakes on the beer.

‘I was going to, but you were too fast for me.’

The bloke down the bar threw back his head and gave a short hard laugh.

The barman looked at the bloke and then looked back at me. The movement took him about thirty seconds. It took him another thirty seconds to decide not to call me a clever sod. Instead he found a thin glass and poured what was in the mug into it and topped it up from the pumps. After another fascinating minute the drink was in front of me.

‘How much?’ I said.

‘One and ten,’ said the barman.

I gave him one and ten and went and sat down on one of the leatherette seats as far away from everybody else as possible. I took a long drink and settled down to wait. I was expecting her any minute.

Quarter of an hour passed and I got up and went over to the bar and got Speedy to pull me another pint. I walked over to my seat again, and out of sight, up a flight of stairs, a phone began to ring. The landlord stopped looking at what was or was not in the till and came round the bar and went up the stairs. I sat down and took a sip of my pint and the landlord reappeared at the foot of the stairs.

‘Is there a Mr Carter in the bar?’ he said, looking straight at me with that expression all publicans have when they answer the phone for somebody else.

I stood up.

‘That’s me,’ I said.

He walked back to the bar without bothering to go into any further details. I walked over to the foot of the stairs and followed the distant sounds of the Coronation Street music until I arrived on the landing where the receiver was dangling from the payphone. I picked it up.

‘Hallo?’ I said.

‘Jack Carter?’ she said.

‘You were supposed to be here quarter of an hour ago.’

‘I know. I can’t come.’

‘Why not?’

‘Me husband. He’s changed shifts. Ten to two.’

I didn’t say anything.

‘I’ve made all the arrangements,’ she said.

‘What time?’

‘Half-past nine.’

‘Did you get the flowers?’

‘Yes.’

I took out a cigarette.

‘Is Doreen at the house?’

‘No. She’s staying with a friend.’

‘Who’s with him then?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘He’s not on his own, is he?’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Well you’d better go round and find out then.’

‘I can’t.’

‘Why not?’

‘Same reason as I couldn’t meet you.’

Silence.

‘Look,’ I said, ‘when can I see you?’

‘You can’t.’

‘Will you be there tomorrow?’

‘No.’

‘Now look …’

‘Door’s on the latch,’ she said. ‘He’s in front room.’

She rang off. I looked at the dead receiver for a few seconds, then put it back on the hook and went down the stairs and finished my pint standing up. Then I picked up my holdall and went out into the rain.

I walked away from The George, turning left down a dark street of terraced houses with narrow front gardens. Above the rain and the blackness low clouds touched with pink from the steelworks sidled across the sky. I turned left again into another street exactly the same as the first except that at the end of it was a stretch of narrow road that ran out of the town between the steelworks and up into the wolds. I walked to the end of the street and opposite me on the other side of the exit road was Parker’s Garage And Car Hire.

I crossed the road and tapped on the office door. Nobody was in sight. I tapped again, harder. A door beyond the filing cabinet opened. A man in overalls and a woollen hat with a bobble on top appeared. He crossed the office and opened the door.

He looked into my face and waited for me to tell him what I wanted.

‘I’d like to hire a car,’ I said.

‘How long for?’ he said.

‘Only for a few days,’ I said. ‘I shan’t be staying long.’

I drove up through the town but via the back routes that paralleled the High Street until I came to Holden Street, a street in which I knew every other house did bed and breakfast; after Frank had been buried I didn’t want to operate from the house, not with Doreen around. I didn’t want her involved unless I could help it. I found one with a garage and parked the car in front of the house, walked up the path and knocked on the door and waited.

The house had gabled windows and a mean little porch. The top half of the front door was panelled in opaque glass with a border of little squares of coloured glass running along the top and the two sides. On either side of the door there were two more panels exactly the same except that they were narrower. Inside the hall a shadow approached the front door and opened it.

She wasn’t bad. About forty, probably the right side of it, hair permed, squarish face, well powdered, big tits, open-necked blouse shoved tight into her skirt. No nonsense with the wrong people but what about the right ones?

She looked as though she might be pleased to see me.

‘Am I in luck?’ I said.

‘What for?’ she said.

‘A room. Have you any vacant?’

‘We have.’

‘Oh, good,’ I said. She stepped back to let me in. I hesitated.

‘Look,’ I said, ‘the point is, I don’t actually need one right now, tonight that is, it’ll be tomorrow and Saturday, maybe Sunday.’

She altered her stance, resting all her weight on one leg.

‘Oh, yes?’ she said.

‘Yes, you see. I’m staying with a friend for tonight, but you know how it is, it won’t be convenient tomorrow, you know.’

‘Her husband changes shifts tomorrow, does he?’

‘Well, er, it’s not exactly like that,’ I said.

‘No,’ she said, beginning to turn away, ‘it never is.’

‘There’s one other thing,’ I said.

She turned back and adopted the stance again.

‘See, I’ve got a car, and I know it’d be all right if I left it in the road, but I notice you’ve got a garage and I was wondering if it was empty if maybe I could put it in there. Tonight, like.’

She carried on looking at me.

‘I mean,’ I said, ‘I’ll pay.’

She looked at me a bit longer.

‘Well, you can hardly park it outside her house, can you?’ she said.

‘Thanks,’ I said, following her in, ‘that’s very nice of you, it really is.’

‘I know,’ she said.

She began to go up the stairs. Her legs were all right, and so was her bum, muscular but not as big as it would have been if she didn’t look after herself. When she got to the top of the stairs she turned round while I was still watching her.

‘Traveller are you?’ she said.

‘You could say that,’ I said.

‘I see,’ she said.

She crossed a landing and opened a door.

‘Will this do?’ she said.

‘Oh yes,’ I said. ‘Just the job.’ I looked all round to show her how much I appreciated it. ‘Just the job.’ I took my wallet out. ‘Look, I’ll pay now and if you like I’ll pay for tonight just to keep the room open.’

‘That’d be a bloody silly thing to do,’ she said. ‘You’re first one since Monday.’

‘Oh, well, if you’re sure,’ I said. ‘How much?’

‘Fifty bob for two nights. Bed and breakfast. A pound’ll do for garage. Let us know Sunday morning if you’re staying.’

I took out the money and gave it to her. She folded it up and pushed it in her skirt pocket. It was a tight fit.

‘And as I say,’ I said, ‘I’ll pop round tomorrow tea-time and move it then if that’s all right.’

‘Whenever you like.’

‘Good,’ I said.

We walked down the stairs. At the door she said:

‘I’ll open garage for you.’

I got in the car, reversed it and drove it up the bit of drive and sat there. She pushed up the sliding door. I drove in and got out.

‘Look,’ I said, ‘will you be in all day tomorrow?’

‘Why?’

‘Well, I might need the car tomorrow afternoon and I’d like to collect it if you’ll be here.’

‘I’ll be here all day after twelve,’ she said.

‘Oh, good,’ I said. ‘Fine.’

I walked out of the garage. I turned to face her.

‘And thanks again.’

She just stared at me with no expression on her face although there was something there way back that might have been a smile, although if she’d have allowed it to surface it would have been a sarcastic one at that. She stopped staring and began to close the garage door.

I walked down the drive and on to the pavement and turned in the direction of the High Street. I smiled. It amused me, the picture she’d got of me, the way she thought she’d got me weighed up. It might turn out to be helpful.

As I got closer to the High Street I noticed it wasn’t raining any more.

I turned left and walked up the High Street. I passed the Oxford Cinema and Eastoes Remnants and Walton’s sweetshop. When we were lads Walton’s doorway was where we always used to stand and watch the world go by. It was the best doorway in the High Street. Big enough to accommodate about twelve lads and in winter it was the least draughty. Pecker Wood, Arthur Coleman, Piggy Jacklin, Nezzer Eyres, Ted Rose, Alan Stamp. We all used to congregate there before the pictures and if we didn’t have the money for the pictures we’d stand there until it was time for us to go home. Jack Coleman, Howard Shepherdson, Dave Patchett. I wondered what had happened to them all.

And of course Frank. But I knew what had happened to him.

And that was something I was going to put right.

Now I was at Jackson Street. On the corner where Rowson’s Grocers used to be was the same shop with the same thirties front but it had been painted yellow (the woodwork, the window frame) and instead of Rowson’s Family Grocer on the fascia it said Hurdy Gurdy in Barnum and Bailey lettering and behind the glass instead of Dandelion and Burdock bottles on faded yellow crêpe paper and instead of Player’s Airmen showcards and Vimto signs there were poove clothes and military uniforms and blow-ups of groups. The shop butted up against the row of villa-type bay-windowed houses that ran down one side of Jackson Street and up the other. At the end of the street a long way away was an iron railing fence and beyond that there used to be the waste ground, the browny yellow grass that led you to the drain, the narrow soggy dyke where Frank and I and others would go up and drop down out of sight of the villas and do anything we wanted to do. At least, I used to, and some of the others, but when Valerie Marshbanks showed everybody her knickers and charged a penny a wank, in the bushes, one at a time with Christine Hall who liked to watch, Frank would never be there, but he’d know what was going on, and when I’d get home, he’d be reading his comic, and he wouldn’t say anything to me, he’d just make me feel fucking awful, and very often he’d keep it up so long that Mam would tell him to straighten his bloody face up else get to bed and he’d just pick up his comic and go up, not looking at me. And when I’d go up, the light would be off, and I’d know he was awake, and that would be worse, having to get in bed in the dark listening to him thinking. I wouldn’t be able to get to sleep for ages because he’d be there awake and I’d be awake because I hardly dared breathe knowing he was thinking about me.

I walked along Jackson Street. Now at the end the railings were still there and some of the grass, but the dyke wasn’t, it had been filled in and there was a small light engineering works, yellow brick under the street light with a lathe on overtime inside.

I got to number 48. The curtains were drawn, of course, but there was a light on in the hall illuminating the frosted glass panels and the privet hedge four feet away from the bay windows.

I opened the front door.

There was new wallpaper on the wall, contemporary, with lobster pots and fishermen’s nets and grounded single-masted yachts, all light browns and pale greens. He’d hardboarded the banisters in, and painted the hardboard and put pictures going upwards below the rail. There was a crimson fitted carpet on the hall and going up the stairs and the light fitting was triple-stalked in some fake brassy material.

I went into the scullery.

On either side of the chimney breast he’d built units in tongue and groove. On one side there was the TV neatly boxed in and some little open compartments with things like framed photos and glass ornaments and fruit bowls in them. One compartment had newspapers, the TV Times and the Radio Times neatly slotted into it. The unit on the other side was for his books.

There were rows of Reader’s Digest, of Wide World, of Argosy, of Real Male, of Guns Illustrated, of Practical Handyman, of Canadian Star Weekly, of National Geographic. They were all on the bottom shelves. Above were the paperbacks. There was Luke Short and Max Brand and J. T. Edson and Louis L’Amour. There was Russell Braddon and W. B. Thomas and Guy Gibson. There was Victor Canning and Alistair Maclean and Ewart Brookes and Ian Fleming. There was Bill Bowes and Stanley Matthews and Bobby Charlton. There was Barbara Tuchman and Winston Churchill and General Patton and Audie Murphy. Above these were his records. Band of the Coldstream Guards, Eric Coates, Stan Kenton, Ray Anthony, Mel Tormé, Frankie Laine, Ted Heath, This is Hancock, Vaughan Williams.

His slippers were on the tiled hearth. A black leather swivel chair was angled to face in the direction of the television.

There was no fire in the grate.

I looked through into the kitchen. It was tidy. The cherry-red formica-faced sink unit had been given a wash down. There was no rubbish in the rubbish bucket. There was an empty dog bowl on the floor.

I went back into the scullery and opened the adjoining door to the front room. On the mantelpiece there was a small lamp with a crimson shade and I switched it on.

There were not many flowers. There was my wreath, and a lot of flowers from Margaret, and another wreath from Doreen.

The head of the coffin was dead centre to the middle of the bay window and the coffin cut the room in half. Next to the coffin and facing it was a dining-room chair. I went over to where the chair was and looked into the coffin. I hadn’t seen him for such a long time. Death didn’t really make much difference at all; the face just reassembled the particles of memory. And as usual when you see someone dead who you’ve seen alive it was impossible to imagine the corpse as being related to its former occupant. It had that porcelain look about it. I felt that if I tapped it on the forehead with my knuckle there would be a pinging sound.

‘Well, Frank,’ I said. ‘Well, well.’

I stood there for a bit longer then sat down in the dining chair.

I said a few words although I don’t know what I said and bowed my head on the edge of the casket for a few minutes then I sat up and undid my coat and took out my fags. I lit up and blew out the smoke slowly and looked at the last of Frank.

Looking at him I found it hard to realise I’d ever known him. All the things about him that I remembered in my mind’s eye didn’t seem real. They seemed like bits of a film. And even when I saw myself in the flashbacks, as you do, you get outside yourself, I didn’t seem real either, neither did the settings or the colours or the way the clouds rushed across the sky while we were doing something particular underneath them.

I took the flask out and had a pull. I looked back at Frank. I stayed there for a minute, looking at him like that, then I screwed the cap back on and walked into the scullery closing the door behind me.

I went into the hall and up the stairs. I opened the first door on the landing. It was Doreen’s room. It used to be mine and Frank’s. The wallpaper had guitars and musical notes and microphones as a pattern. There were pictures of the Beatles, and the Moody Blues, and the Tremeloes and Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Tich; centre-spreads from beat magazines sellotaped on the walls. There were records and a record player in a cupboard unit next to her single bed which was made up to look like a divan, pushed against one wall. There was a whitewood dressing table opposite the bed and next to that a rod and curtain across the corner made a wardrobe. A drawer of the dressing table was open and a stocking was hanging out. I went into Frank’s room. It used to be Mam and Dad’s. There was a pre-war bed and a pre-war tallboy and a pre-war wardrobe and patterned lino on the floor. Everything was very tidy. On the mantelpiece was a framed photograph of me and Frank as lads in our best suits outside the Salvation Army. We hadn’t been Salvationists but we used to go on Sunday mornings and sing because we used to enjoy it as a change.

I sat down on Frank’s bed and it creaked and sagged. The lino was green and cold. I dropped my cigarette on the floor and put my foot on it. I sat there for quite a time before I went downstairs and got my holdall and brought it back upstairs with me.

I began to get ready for bed when I remembered something. I looked round the room and wondered if he’d kept it. Why should he? But then, why should he give it away? I walked over to the wardrobe and opened the door just on the off-chance.

The stock gleamed beneath the hanging line of Frank’s clothes. I squatted down and reached inside and took hold of it just above the trigger. The barrel clattered against the back of the wardrobe. The sound was hollow and it echoed coldly on the patterned lino. I pulled the gun out of the wardrobe. Where the stock had been, tucked behind a pair of shoes, there was a box of cartridges. I took that out too. I carried the gun and the box over to the bed and sat down again.

I looked at the gun. Christ, we’d sweated to save up for it. Nearly two years, both of us. No pictures, no football, no fireworks. We’d made a pact: if one of us broke it, the other was to take all the money and spend it on whatever he wanted. I knew Frank wouldn’t break the pact. But I thought I might. And so did he. Somehow, though, I’d stuck to it.

And then we’d sweated when we’d finally got it. Sweated in case our dad ever found out. He would have broken it in two and made us watch him do it. We used to keep it round Nezzer Eyres’s and pick it up on Sundays when we wanted it. But once we’d collected it we never felt safe until we’d biked at least half a dozen streets away from Jackson Street.

We used to take turns at carrying it. When it was my turn, I always used to think my time went quicker than when Frank was carrying it. We went all over with it. Back Hill, Sanderson’s Flats, Fallow Fields. But the best place was the river bank. It was a nine-mile bike ride but it was worth it. The river was broad, two miles in parts and the banks were always deserted, and we used to like it best in winter when the wind raced up the estuary under the broad grey sky, and we were all wrapped up, striding along in front of the wind, carrying the gun, popping it off at nothing.

Those times were the best times I ever had as a lad. Just alone with Frank down on the river. But that was before he’d begun to hate my guts.

Not that I’d exactly been full of brotherly love for him before I’d left the town.

He’d been so fucking po-faced about everything. Siding with our dad all the time, although never hardly saying anything. He’d just let me know by the way he’d looked at me. Maybe that’s why I’d hated him sometimes; I could tell how right about me he’d thought he was. Well, he was right. So bloody what? There’d been no need for him to be that way. I’d been the same person after he’d started hating me as before. It was just that he’d got to know a few things. And just because he didn’t see them my way that was it as far as I was concerned. The less said about me and to me the better. He couldn’t see that the dust-up I’d had with our dad was mainly because of the way Frank was towards me.

But all that was past history. As dead as Frank. Nothing could be done about it now. But there were some things that I’d be able to put straight. Just for the sake of the past history.

FRIDAY

I could tell it was windy out before I could hear the wind. It was the daylight, what bit that was getting through the cracks of the curtains. I knew it was windy because of the kind of daylight it was.

I rolled on to my back and looked at my watch. It was quarter to eight. I reached out and grabbed a fag and smoked it looking up at the reflected light on the ceiling getting depressed with the greeny-brown gloom, getting impatient with myself for not getting up but lying there anyway, just smoking, balancing the packet on my chest for an ashtray.

Finally I swung out of bed and went into the cold bathroom and got ready for the day. The wind swished about outside beyond the bright frosted glass.

I went downstairs and switched on the wireless. While Family Choice warmed up I went into the kitchen and found the tea caddy and put the kettle on the gas. I made the tea and began to put my cufflinks in.

The back door opened and Doreen came in. She was wearing a black coat, a nice-looking one, short, and she had something on the Garbo lines on her head. Her pale gold hair was long and some of it was placed so that it fell down in front of her shoulders, between her shoulders and neck, almost on her breasts.

She looked at me for a minute before shutting the door. After she’d shut it she didn’t move except to take her hat off and put it on the drainer and then just stood there with her hands in her high pockets and feet together looking at the floor. She looked more bad tempered than unhappy.

I finished doing my cufflinks.

‘Hello, Doreen,’ I said.

‘’Lo,’ she said.

‘How are you feeling?’ I said.

‘How do you think?’

I began to pour out the tea.

‘I’m very sorry about your dad,’ I said. She didn’t say anything. I offered her a cup of tea but she turned away.

‘Enjoying the music, are you?’ she said.

‘The house seemed cold,’ I said. ‘Besides …’ She shrugged and went into the scullery and sat down on Frank’s chair, her hands still in her pockets, her feet still together. I followed her in and sat on the arm of the divan, sipping my tea.

‘I really am sorry, Doreen,’ I said. ‘He was my brother, you know.’

She didn’t say anything.

‘I don’t know what to say,’ I said.

Silence.

I didn’t want to ask her anything outright before the funeral so I said:

‘I couldn’t believe it. I just couldn’t believe it. He was always so careful.’

Silence.

‘I mean, he only drank halves.’

Silence.

‘And not turning up for work.’

Two tears began rolling down Doreen’s face.

‘He wasn’t worried about anything, was he? I mean, something on his mind, like, that’d make him careless, through worry, like.’

Silence. The tears rolled further.

‘Doreen?’

She whirled up out of the chair.

‘Shut up,’ she shouted, the tears coming faster. ‘Shut up. I can’t bear it.’

She ran into the kitchen and stopped in front of the sink, head bowed, shoulders heaving, her arms by her side.

‘Can’t bear what, love?’ I said standing behind her. ‘What is it you can’t bear?’

‘Me dad,’ she said. ‘Me dad. He’s bloody dead, isn’t he?’ She turned towards me. ‘Isn’t he?’

I put my arms up and she fell against me. I pressed her to me and let her get it over with.

After a while she straightened up and I poured her a fresh cup of tea. This time she took it. I sat down on the red leatherette-topped high stool next to the sink unit and watched her alternately drinking out of and looking into the cup. I wondered if it had all been just because her dad was dead through in the front room or was there something else. I couldn’t really tell. Last time I saw her was eight years ago and then she’d been seven so I didn’t know what she was like. I could guess though.