4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

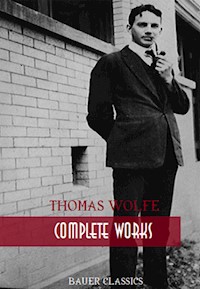

- Herausgeber: Bauer Books

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

Godfrey Morgan: A Californian Mystery (French: L'École des Robinsons, literally The School for Robinsons), also published as School for Crusoes, is an 1882 adventure novel by French writer Jules Verne. It tells of a young adventurer, Godfrey Morgan, and his deportment instructor, Professor T. Artelett, who embark on a round-the-world ocean voyage. Their ship is wrecked and they are cast away on a remote island, where they rescue and befriend an African slave, Carefinotu.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Jules

Godfrey Morgan: A Californian Mystery (Illustrated Edition)

Table of contents

“Going! Going!” CHAPTER I.

IN WHICH THE READER HAS THE OPPORTUNITY OF BUYING AN ISLAND IN THE PACIFIC OCEAN.“An island to sell, for cash, to the highest bidder!” said Dean Felporg, the auctioneer, standing behind his rostrum in the room where the conditions of the singular sale were being noisily discussed.

“Island for sale! island for sale!” repeated in shrill tones again and again Gingrass, the crier, who was threading his way in and out of the excited crowd closely packed inside the largest saloon in the auction mart at No. 10, Sacramento Street.

The crowd consisted not only of a goodly number of Americans from the States of Utah, Oregon, and California, but also of a few Frenchmen, who form quite a sixth of the population.

Mexicans were there enveloped in their sarapes; Chinamen in their large-sleeved tunics, pointed shoes, and conical hats; one or two Kanucks from the coast; and even a sprinkling of Black Feet, Grosventres, or Flatheads, from the banks of the Trinity river.

The scene is in San Francisco, the capital of California, but not at the period when the placer-mining fever was raging—from 1849 to 1852. San Francisco was no longer what it had been then, a caravanserai, a terminus, an inn, where for a night there slept the busy men who were hastening to the gold-fields west of the Sierra Nevada. At the end of some twenty years the old unknown Yerba-Buena had given place to a town unique of its kind, peopled by 100,000 inhabitants, built under the shelter of a couple of hills, away from the shore, but stretching off to the farthest heights in the background—a city in short which has dethroned Lima, Santiago, Valparaiso, and every other rival, and which the Americans have made the queen of the Pacific, the “glory of the western coast!”

It was the 15th of May, and the weather was still cold. In California, subject as it is to the direct action of the polar currents, the first weeks of this month are somewhat similar to the last weeks of March in Central Europe. But the cold was hardly noticeable in the thick of the auction crowd. The bell with its incessant clangour had brought together an enormous throng, and quite a summer temperature caused the drops of perspiration to glisten on the foreheads of the spectators which the cold outside would have soon solidified.

“An island! an isle to sell!” repeated Gingrass. “But not to buy!” answered an Irishman, whose pocket did not hold enough to pay for a single pebble. “An island which at the valuation will not fetch six dollars an acre!” said the auctioneer. “And which won’t pay an eighth per cent.!” replied a big farmer, who was well acquainted with agricultural speculations. “An isle which measures quite sixty-four miles round and has an area of two hundred and twenty-five thousand acres!” “An isle with forests still virgin!” repeated the crier, “with prairies, hills, watercourses—” “For two years?” “To the end of the world!” “Beyond that?” “A freehold island!” repeated the crier, “an island without a single noxious animal, no wild beasts, no reptiles!—” “No birds?” added a wag. “No insects?” inquired another. “Pass it round!” said a voice as if they were dealing with a picture or a vase. And the room shouted with laughter, but not a half-dollar was bid. It was hardly likely that any one would be mad enough to buy it on the terms. And all the time the crier was heard with,— “An island to sell! an island for sale!” And there was no one to buy it. “No,” answered the auctioneer, “but it is not impossible that there are, and the State abandons all its rights over the gold lands.” “Haven’t you got a volcano?” asked Oakhurst, the bar-keeper of Montgomery Street. “No volcanoes,” replied Dean Felporg, “if there were, we could not sell at this price!” An immense shout of laughter followed. “An island to sell! an island for sale!” yelled Gingrass, whose lungs tired themselves out to no purpose. Perfect silence. “If nobody bids we must put the lot back! Once! Twice! The crowd, suddenly speechless, turned towards the bold man who had dared to bid. HOW WILLIAM W. KOLDERUP, OF SAN FRANCISCO, WAS AT LOGGERHEADS WITH J. R. TASKINAR, OF STOCKTON. A man extraordinarily rich, who counted dollars by the million as other men do by the thousand; such was William W. Kolderup. But was it probable? Was it even possible? “Going at twelve hundred thousand dollars!” repeated Gingrass the crier. “You could safely bid more than that,” said Oakhurst, the barkeeper; “William Kolderup will never give in.” “He knows no one will chance it,” answered the grocer from Merchant Street. “Nobody speaks?” asked Dean Felporg. Nobody spoke. “Once! Twice!” “Once! Twice!” repeated Gingrass, quite accustomed to this little dialogue with his chief. “Going!” “Going!” “For twelve—hundred—thousand—dollars—Spencer—Island— com—plete!” “For twelve—hundred—thousand—dollars!” “That is so? No mistake?” “No withdrawal?” “For twelve hundred thousand dollars, Spencer Island!” The public could not have been more absorbed in the face of a summary application of the law of Justice Lynch! But before the sharp rap could be given, a voice was heard giving utterance to these four words,— “Thirteen—hundred—thousand—dollars!” But who was the reckless individual who had dared to come to dollar strokes with William W. Kolderup of San Francisco? It was J. R. Taskinar, of Stockton. “Thirteen hundred thousand dollars!” Everybody as we have seen turned to look at him. “Fat Taskinar!” It was the voice of Dean Felporg which broke the spell. “For thirteen hundred thousand dollars, Spencer Island!” declaimed he, drawing himself up so as to better command the circle of bidders. “Fifteen hundred thousand!” retorted J. R. Taskinar. “Sixteen hundred thousand!” “Seventeen hundred thousand!” “Seventeen hundred thousand dollars!” repeated the auctioneer. “Now, gentlemen, that is a mere nothing! It is giving it away!” And one can well believe that, carried away by the jargon of his profession, he was about to add,— “The frame alone is worth more than that!” When— “Seventeen hundred thousand dollars!” howled Gingrass, the crier. “Eighteen hundred thousand!” replied William W. Kolderup. “Nineteen hundred thousand!” retorted J. R. Taskinar. “Two million, four hundred thousand dollars!” he remarked, hoping by this tremendous leap to completely rout his rival. “Two million, seven hundred thousand!” replied William W. Kolderup in a peculiarly calm voice. “Two million, nine hundred thousand!” “Three millions!” Yes! William W. Kolderup, of San Francisco, said three millions of dollars! After a long pause, however, his voice was heard; feeble it is true, but sufficiently audible. “Three millions, five hundred thousand!” “Four millions,” was the answer of William W. Kolderup. “I will be avenged!” muttered J. R. Taskinar, and throwing a glance of hatred at his conqueror, he returned to the Occidental Hotel. THE CONVERSATION OF PHINA HOLLANEY AND GODFREY MORGAN, WITH A PIANO ACCOMPANIMENT. “Good!” he said. “She and he are there! A word to my cashier, and then we can have a little chat.” “Are you listening?” she said. “Of course.” “Yes! but do you understand it?” “Do I understand it, Phina! Never have you played those ‘Auld Robin Gray’ variations more superbly.” “But it is not ‘Auld Robin Gray,’ Godfrey: it is ‘Happy Moments.’” Her dreams were when she was asleep, not when she was awake. She was not asleep now, and had no intention of being so. “Godfrey?” she continued. “Phina?” answered the young man. “Where are you now?” “Near you—in this room—” “If we must part, it had better be before marriage than afterwards!” And thus it was that she had spoken to Godfrey in these significant words. “No! You are not near me at this moment—you are beyond the seas!” Phina had understood him, and without more discussion was about to bring matters to a crisis, when the door of the room opened. “Well,” said he, “there is nothing more now than for us to fix the date.” “The date?” answered Godfrey, with a start. “What date, if you please, uncle?” “The date of your wedding!” said William W. Kolderup. “Not the date of mine, I suppose!” “Godfather Will,” answered the lady. “It is not of a wedding that we are going to fix the date to-day, but of a departure.” “A departure!” “Yes, the departure of Godfrey,” continued Phina, “of Godfrey who, before he gets married, wants to see a little of the world!” “Yes; I do, uncle,” said Godfrey gallantly. “And for how long?” “For eighteen months, or two years, or more, if—” “If—” “If you will let me, and Phina will wait for me.” “Wait for you! An intended who intends until he gets away!” exclaimed William W. Kolderup. “What!” exclaimed William W. Kolderup, “you consent to give your bird his liberty?” “Yes, for the two years he asks.” “And you will wait for him?” “You are serious,” he asked. “Quite serious!” interrupted Phina, while Godfrey contented himself with making a sign of affirmation. “You want to try travelling before you marry Phina! Well! You shall try it, my nephew!” He made two or three steps and stopping with crossed arms before Godfrey, asked,— “Where do you want to go to?” “Everywhere.” “And when do you want to start?” “When you please, Uncle Will.” “All right,” replied William W. Kolderup, fixing a curious look on his nephew. Then he muttered between his teeth,— Perhaps Phina’s heart was nearly full, she had made up her mind to say nothing. It was then that William W. Kolderup, without noticing Godfrey, approached the piano. “Phina,” said he gravely, “you should never remain on the ‘sensible’!” And with the tip of his large finger he dropped vertically on to one of the keys and an “A natural” resounded through the room. CHAPTER IV. IN WHICH T. ARTELETT, OTHERWISE TARTLET, IS DULY INTRODUCED TO THE READER. “He was born on the 17th July, 1835, at a quarter-past three in the morning. “His height is five feet, two inches, three lines. “His girth is exactly two feet, three inches. “His weight, increased by some six pounds during the last year, is one hundred and fifty one pounds, two ounces. “He has an oblong head. “His hair, very thin above the forehead, is grey chestnut, his forehead is high, his face oval, his complexion fresh coloured. “His nose is of medium size, and has a slight indentation towards the end of the left nostril. “His cheeks and temples are flat and hairless. “His ears are large and flat. “His mouth, of middling size, is absolutely free from bad teeth. “A small mole ornaments his plump neck—in the nape. “Finally, when he is in the bath it can be seen that his skin is white and smooth. “As you think best!” answered the professor. “Sir,” answered Tartlet, “my pupil, Godfrey, will do honour to the country of his birth, and—” “I thought,” continued the latter, “that you might feel a little regret at separating from your pupil?” “The regret will be extreme,” answered Tartlet, “but should it be necessary—” “It is not necessary,” answered William W. Kolderup, knitting his bushy eyebrows. “Ah!” replied Tartlet. “You will go!” answered William W. Kolderup like a a man with whom discussion was useless. “And when am I to start?” demanded he, trying to get back into an academical position. “In a month.” “And on what raging ocean has Mr. Kolderup decided that his vessel should bear his nephew and me?” “The Pacific, at first.” “And on what point of the terrestrial globe shall I first set foot?” And thus was Professor Tartlet selected as the travelling-companion of Godfrey Morgan. IN WHICH THEY PREPARE TO GO, AND AT THE END OF WHICH THEY GO FOR GOOD. In short, Godfrey was enchanted. Phina, anxious without appearing to be so, was resigned to this apprenticeship. “Ah! you want to travel,” muttered he every now and then; “travel instead of marrying and staying at home! Well, you shall travel.” Preparations were immediately begun. But it was not thus that the nephew and heir of the nabob of Frisco was to travel. “May five hundred thousand Davy Joneses drag me to the bottom if ever I had a job like this before!” “Good-bye, Phina!” “Good-bye, Godfrey!” “May Heaven protect you!” said the uncle. “Never, Uncle Will! Good-bye, Phina!” “Good-bye, Godfrey!” IN WHICH THE READER MAKES THE ACQUAINTANCE OF A NEW PERSONAGE. The voyage had begun. There had not been much difficulty so far, it must be admitted. Professor Tartlet, with incontestable logic, often repeated,— “Any voyage can begin! But where and how it finishes is the important point.” During the morning of the 12th of June a very unexpected incident occurred on board. “Captain!” he said. “What’s up?” asked Turcott, sailor as he was, always on the alert. “Here’s a—Chinee!” said the boatswain. “At the bottom of the hold!” exclaimed Turcott. “Well, by all the— somethings—of Sacramento, just send him to the bottom of the sea!” “All right!” answered the boatswain. Captain Turcott made a sign to his men to leave the unhappy intruder alone. “Who are you?” he asked. “A son of the sun.” “And what is your name?” “Seng Vou,” answered the Chinese, whose name in the Celestial language signifies “he who does not live.” “And what are you doing on board here?” “I am out for a sail!” coolly answered Seng Vou, “but am doing you as little harm as I can.” “Really! as little harm!—and you stowed yourself away in the hold when we started?” “Just so, captain.” “So that we might take you for nothing from America to China, on the other side of the Pacific?” “If you will have it so.” “And if I don’t wish to have it so, you yellow-skinned nigger. If I will have it that you have to swim to China.” “I will try,” said the Chinaman with a smile, “but I shall probably sink on the road!” “Well, John,” exclaimed Captain Turcott, “I am going to show you how to save your passage-money.” “Captain,” he said, “one more Chinee on board the is one Chinee less in California, where there are too many.” “A great deal too many!” answered Captain Turcott. His presence on board put into Captain Turcott’s head an idea which his mate probably was the only one to understand thoroughly. “He will bother us a bit—this confounded Chinee!—after all, so much the worse for him.” “What ever made him stow himself away on board the ?” answered the mate. “To get to Shanghai!” replied Captain Turcott. “Bless John and all John’s sons too!” CHAPTER VII. IN WHICH IT WILL BE SEEN THAT WILLIAM W. KOLDERUP WAS PROBABLY RIGHT IN INSURING HIS SHIP. Godfrey bore the trial of the ship’s motion without even losing his good-humour for a moment. Evidently he was fond of the sea. But Tartlet was not fond of the sea, and it served him out. “Air! air!” he gasped. “Dunno! barometer is not very promising!” was the invariable answer of the captain, knitting his brows. “Shall we soon get there?” “Soon, Mr. Tartlet? Hum! soon!” “And they call this the Pacific Ocean!” repeated the unfortunate man, between a couple of shocks and oscillations. “No,” said he with a lifeless look at his pupil, “it is not impossible for us to capsize.” “Take it quietly, Tartlet,” replied Godfrey. “A ship was made to float! There are reasons for all this.” “I tell you there are none.” Towards midnight then Godfrey dressed, and, wrapping himself up warmly, went on deck. The men on watch were forward, Captain Turcott was on the bridge. “Has the wind changed?” he said to himself. And extremely glad at the circumstance he mounted the bridge. Stepping up to Turcott,— “Captain!” he said. “You, Mr. Godfrey, you—on the bridge?” “Yes, I, captain. I came to ask—” “What?” answered Captain Turcott sharply. “If the wind has not changed?” “No, Mr. Godfrey, no. And, unfortunately, I think it will turn to a storm!” “But we now have the wind behind us!” “Wind behind us—yes—wind behind us!” replied the captain, visibly disconcerted at the observation. “But it is not my fault.” “What do you mean?” “I mean that in order not to endanger the vessel’s safety I have had to put her about and run before the storm.” “That will cause us a most lamentable delay!” said Godfrey. The mate on the poop, his telescope at his eye, was looking towards the north-east. Godfrey approached him. “Well, sir,” said he gaily, “to-day is a little better than yesterday.” “Yes, Mr. Godfrey,” replied the mate, “we are now in smooth water.” “And the is on the right road!” “Not yet.” “Not yet? and why?” “Because we have evidently drifted north-eastwards during this last spell, and we must find out our position exactly.” “But there is a good sun and a horizon perfectly clear.” “At noon in taking its height we shall get a good observation, and then the captain will give us our course.” “Where is the captain?” asked Godfrey. “He has gone off.” “Gone off?” “How long ago?” “About an hour and a half!” “Ah!” said Godfrey, “I am sorry he did not tell me. I should like to have gone too.” “You were asleep, Mr. Godfrey,” replied the mate, “and the captain did not like to wake you.” “I am sorry; but tell me, which way did the launch go?” “Over there,” answered the mate, “over the starboard bow, northeastwards.” “And can you see it with the telescope?” “No, she is too far off.” “But will she be long before she comes back?” “She won’t be long, for the captain is going to take the sights himself, and to do that he must be back before noon.” Two hours passed. It was not until half-past ten that a light line of smoke began to rise on the horizon. It was evidently the steam launch which, having finished the reconnaissance, was making for the ship. At a quarter-past eleven, Captain Turcott hailed and boarded the . “Well, captain, what news?” asked Godfrey, shaking his hand. “Ah! Good morning, Mr. Godfrey!” “And the breakers?” “We are going ahead then?” said Godfrey. “Yes, we are going on now, but I must first take an observation.” “Shall we get the launch on board?” asked the mate. He jumped out of bed, slipped on his clothes, his trousers, his waistcoat and his sea-boots. Almost immediately a fearful cry was heard on deck, “We are sinking! we are sinking!” The whole crew were on deck, hurrying about at the orders of the mate and captain. “A collision?” asked Godfrey. “I don’t know, I don’t know—this beastly fog—” answered the mate; “but we are sinking!” “Sinking?” exclaimed Godfrey. “I’ll look after him!—We are only half a cable from the shore!” “But you?” “My duty compels me to remain here to the last, and I remain!” said the captain. “But get off! get off!” Godfrey still hesitated to cast himself into the waves, but the water was already up to the level of the deck. All this was the work of a minute. A few minutes afterwards, amid shouts of despair, the lights on board went out one after the other. Doubt existed no more; the had sunk head downwards! WHICH LEADS GODFREY TO BITTER REFLECTIONS ON THE MANIA FOR TRAVELLING. He began again, many times, turning successively to every point of the horizon. Absolute silence. “Alone! alone!” he murmured. Nothing appeared through the mist. Up to the present, however, there was no sign of any shore. Nothing yet indicated the proximity of dry land, even in this direction. “Land! land!” exclaimed Godfrey. And he stretched his hands towards the shore-line, as he knelt on the reef and offered his thanks to Heaven. From the place which Godfrey occupied, his view was able to grasp the whole of this side. “To land! to land!” he said to himself. Nothing. The launch even was not there, and had probably been dragged into the common abyss. No! Nothing along the whole length of the breakers, which the last ripples of the ebb had now left bare. Godfrey was alone! He could only count on himself to battle with the dangers of every sort which environed him! As he called up these remembrances his heart swelled, and in spite of his resolution a tear rose to his eyes. Who else but he had already touched the shore, seeking a companion who was seeking him? “Let us get on!” said Godfrey to himself. Godfrey was not ten paces away from it, when he stopped as if rooted to the soil, and exclaimed,— “Tartlet!” It was the professor of dancing and deportment. Godfrey rushed towards his companion, who perhaps still breathed. Godfrey spoke to him. Tartlet shook his head, then he gave utterance to a hoarse exclamation, followed by incoherent words. Godfrey shook him violently. “Tartlet! My dear Tartlet!” shouted Godfrey, lightly raising his head. The head with his mass of tumbled hair gave an affirmative nod. “It is I! I! Godfrey!” “In place, miss!” IN WHICH IT IS SHOWN THAT CRUSOES DO NOT HAVE EVERYTHING AS THEY WISH. That done, the professor and his pupil rushed into one another’s arms. “My dear Godfrey!” exclaimed Tartlet. “My good Tartlet!” replied Godfrey. “At last we are arrived in port!” observed the professor in the tone of a man who had had enough of navigation and its accidents. He called it arriving in port! Godfrey had no desire to contradict him. “Take off your life-belt,” he said. “It suffocates you and hampers your movements.” “Do you think I can do so without inconvenience?” asked Tartlet. “Without any inconvenience,” answered Godfrey. “Now put up your fiddle, and let us take a look round.” “Yes! to the first restaurant!” answered Godfrey, nodding his head; “and even to the last, if the first does not suit us.” “I don’t see the town,” remarked Tartlet, who, however, remained on tiptoe. “That is perhaps because it is not in this part of the province!” answered Godfrey. “But a village?” “There’s nothing here.” “Where are we then?” “I know nothing about it.” “What! You don’t know! But Godfrey, we had better make haste and find out.” “Who is to tell us?” “What will become of us then?” exclaimed Tartlet, rounding his arms and lifting them to the sky. “Become a couple of Crusoes!” At this answer the professor gave a bound such as no clown had ever equalled. “Yes, my gallant Tartlet,” answered Godfrey. “Reassure yourself. But in the first place, let us think about matters that are pressing.” “If there are no inhabitants on this land, are there any animals?” asked Godfrey. “Look there, Tartlet!” he exclaimed. And the professor looked, but saw nothing, so much was he absorbed with the thought of this unexpected situation. “And the fire?” said the professor. “Yes! The fire!” said Godfrey. “Doesn’t it do?” he asked. “No,” answered Godfrey. “But in that, as in all things, you must know how to do it.” “These eggs, then?” Tartlet could not make up his mind to imitate him, and contented himself with the shell-fish. It now remained to look for a grotto or some shelter in which to pass the night. “Let us look,” said Godfrey. Tartlet and he then remounted the first line of sandhills and crossed the verdant prairies which they had seen a few hours before. IN WHICH GODFREY DOES WHAT ANY OTHER SHIPWRECKED MAN WOULD HAVE DONE UNDER THE CIRCUMSTANCES. On the morrow, the 27th of June, at the first rays of the rising sun, the crow of the cock awakened them. Godfrey immediately recognized where he was, but Tartlet had to rub his eyes and stretch his arms for some time before he did so. “Is breakfast this morning to resemble dinner yesterday?” was his first observation. “I am afraid so,” answered Godfrey. “But I hope we shall dine better this evening.” “To vary our ordinary,” he said, “here are some shell-fish and half a dozen eggs.” “I should say that nothing was not enough,” said Tartlet drily. Nevertheless, they had to be content with this repast. Tartlet agreed to remain alone, and for several hours to act as shepherd of the flock. He made but one observation,— “If you lose yourself, Godfrey?” Besides the position of the sun, always in the south, rendered it quite certain that the had not crossed the line. A tiny cone, obliquely truncated, overlooked this rugged line and joined on with its gentle slope to the sinuous crest of the hills. A last effort was made! His head rose above the platform of the cone, and then, lying on his stomach, his eyes gazed at the eastern horizon. It was the sea which formed it. Twenty miles off it united with the line of the sky! He turned round. Still sea—west of him, south of him, north of him! The immense ocean surrounding him on all sides! “An island!” In any case, no other island, large or small, high or low, appeared within the range of vision. Godfrey then occupied himself in trying to ascertain if the island was inhabited in the part which he had not yet been able to visit. This was to be looked into on the morrow. It was a false hope. Godfrey took a last look in its direction, and then seeing nothing, glided down the slope, and again plunged beneath the trees. An hour later he had traversed the forest and found himself on its skirt. “Well,” he shouted as he perceived Godfrey some distance off—”and the telegraph office?” “It is not open!” answered Godfrey, who dared not yet tell him anything of the situation. “And the post?” “It is shut! But let us have something to eat!—I am dying with hunger! We can talk presently.” IN WHICH THE QUESTION OF LODGING IS SOLVED AS WELL AS IT COULD BE. “An island!” exclaimed Tartlet. “Yes! It is an island!” “Which the sea surrounds?” “Naturally.” “But what is it?” “I have told you, Phina Island, and you understand why I gave it that name.” “Let us make a start,” said Godfrey. Nothing! always nothing! Well, try it! “At last,” he exclaimed, “there is something which will be a change from our eggs and mussels.” “What? Do you eat those things?” said Tartlet with his customary grimace. “You shall soon see!” answered Godfrey. And he set to work to gather the manzanillas, and eat them greedily. The site was well worth the trouble of looking at, of visiting, and, doubtless, occupying. One of these specimens of —one of the biggest in the group—more particularly attracted Godfrey’s attention. And the young man, catching hold of his companion, dragged him inside the sequoia. The base was covered with a bed of vegetable dust, and in diameter could not be less than twenty feet. “Eh, Tartlet, what do you think of our natural house?” asked Godfrey. “Yes, but the chimney?” answered Tartlet. “Before we talk about the chimney,” replied Godfrey, “let us wait till we have got the fire!” WHICH ENDS WITH A THUNDER-BOLT. “Crusoe before Friday, Crusoe after Friday; what a difference!” thought he. It was evident that there would be no difficulty in catching these fish, but how to cook them? Always this insoluble question! “Ah!” he said. “We have got some roots to-day. Who knows whether we shall have any to-morrow?” “Well, Godfrey, and the camas?” “Of the camas we will make flour and bread when we have got a fire.” “Fire!” exclaimed the professor, shaking his head. “Fire! And how shall we make it?” “I don’t know yet, but somehow or other we will get at it.”Lesen Sie weiter in der vollständigen Ausgabe!