Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

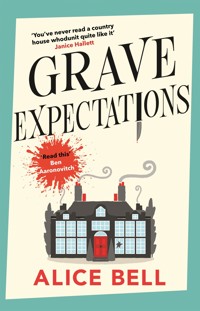

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Grave Expectations

- Sprache: Englisch

A BBC RADIO 2 BOOK CLUB PICK A KINDLE TOP 5 BESTSELLER 'Fast, funny and furious, this book has bags of humour, bags of heart and a proper murder mystery at its core' Janice Hallett Claire and Sophie aren't your typical murder investigators . . . When 30-something freelance medium Claire Hendricks is invited to an old university friend's country pile to provide entertainment for a family party, her best friend Sophie tags along. In fact, Sophie rarely leaves Claire's side, because she's been haunting her ever since she was murdered at the age of seventeen. On arrival at The Cloisters it quickly becomes clear that this family is hiding more than just the good china, as Claire learns someone has recently met an untimely end at the house. Teaming up with the least unbearable members of the Wellington-Forge family - depressive ex-cop Basher and teenage radical Alex - Claire and Sophie determine to figure out not just whodunnit, but who they killed, why and when. Together they must race against incompetence to find the murderer - before the murderer finds them... in this funny, modern, media-literate mystery for the My Favourite Murder generation. 'Read this fabulous book' Ben Aaronovitch 'A delicious mashup of grisly murder, country house and semi-helpful ghosts' Stuart MacBride 'Fresh, funny and hugely enjoyable' Catherine Ryan Howard Readers love GRAVE EXPECTATIONS 'Brilliantly funny!' ***** 'Witty and smart and just a joy to read' ***** 'A genuinely interesting mystery, cosy without being twee' ***** 'I laughed out loud throughout and hardly put it down, loads of clever twists' ***** 'Loved this book, it's fun and well written. Great new take on the genre.' *****

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 473

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

First published in the Great Britain in 2023 by Corvus,an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Alice Bell, 2023

The moral right of Alice Bell to be identified as the author of thiswork has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright,Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 83895 839 8

Trade Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 840 4

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 841 1

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For Colm. hello Colm! iluyu!

and for Jayave atque vale

PART I

You think you will die, but you just keep living, day after day after terrible day.

Charles Dickens, Great Expectations

1

A Dead Girl

The train was two carriages long in its entirety, with rattling single-glazed windows, and it wound its way contentedly along the country line at whatever speed it felt like. It stopped at every tumbledown station it passed through, and this one was so small – a half-length platform of pebble-dashed concrete, covered in ivy at one end and collapsing at the other – that Claire almost didn’t realize it was her stop. In the end it was Sophie who roused her from staring, unseeing, out of the window.

‘Hey,’ she said, waving a hand in front of Claire’s face. ‘I think this is it.’

‘Oh, shit!’

Claire grabbed the bags and clattered out onto the platform just as the engine revved up once more. They turned and watched the train chunter off into the gathering darkness, then took stock. The letters on the sign were starting to peel off, but this was Wilbourne Major all right.

‘Ohmigod,’ Soph commented, as Claire shrugged on her coat. ‘This place really is in the middle of nowhere.’

Claire turned round to look at her. Soph was in her usual bright turquoise velour tracksuit – Claire had almost forgotten what she looked like in anything else – the matching jacket and bottoms separated by a sliver of almost luminous midriff. Her chestnut curls were swept back into a high ponytail, and she had a few sparkly mini hair-claws in the shape of butterflies decorating the sides of her head. In fact it looked as if a giant butterfly had landed in the October gloom. Claire was struck, as she was more and more now that she was entering her thirties, by the strong protective urge she felt towards Sophie.

‘Aren’t we getting picked up? Where the fuck is the car?’ Soph swore a lot – like, a lot a lot.

‘Dunno.’ Claire checked her phone. ‘I haven’t got any signal, of course. Figgy said she’d be here, though.’

‘Let’s go this way…’ Sophie walked off the platform and through the hedge behind it. It turned out that the car park joined almost directly onto the platform, and there was indeed a car waiting on the far side of it. It was a very shiny black Audi.

‘Oof,’ said Sophie, as they walked towards it. ‘How rich are they, again? Maybe this weekend won’t be a total write-off.’

‘I know, right?’

‘Didn’t you say everyone who has an Audi is a dick, though?’

‘Yeah, they totally are. If you ever see someone driving like an arsehole, it’s, like, always an Audi.’

‘Isn’t that like saying everyone who’s rich is an arsehole?’

‘I’m comfortable with that generalization,’ Claire replied, picking at the loose threads in her coat. ‘But shh. That’s Figgy.’

‘Sure, don’t want to offend your rich arsehole friend. LOL.’ Sophie pronounced it el oh el.

Figgy Wellington-Forge opened the driver’s door and unfolded from the car like a sexy deckchair. She was very tall and was wearing a blue-and-white striped, figure-hugging woollen one-piece, as if she was off to an Alpine après-ski and not standing in mizzling rain in an English car park. She seemed exactly the same as she had been back in her university days with Claire.

‘Dah-ling!’ she cried, striding forward and bestowing Claire with four (four!) air-kisses. ‘So good to see you.’ Figgy was one of those people who stretched their vowels to breaking point, so what she actually said was: ‘Seeeeeooo good to seeeyeeew!’

Claire slung the battered rucksack and holdall into the back seat, and Soph slid silently in after them. She sat in the middle because she liked to see the road. Claire sat in the front and then leaned back to fuss with the position of her rucksack, as a pretext to shoot Sophie a warning glance.

‘Right!’ Figgy exclaimed brightly. ‘If we get a bit of a wiggle on, we should get to the house in good time for dinner. Mummy is doing shepherd’s pie.’

Claire considered this. She’d had worse Friday nights than someone’s mum making her shepherd’s pie. It was getting truly dark now. When Claire looked in the rear-view mirror all she saw was the occasional oncoming headlight sparkling off Soph’s lip gloss and her wide, dark eyes. Like most teenagers, Sophie’s emotions passed across her face as quickly and obviously as clouds in front of the sun, but sometimes she switched off entirely and became totally impassive. It was quite scary.

Figgy shivered and put the heaters on full blast, then broke the silence that Claire suddenly realized had gone on for some time. ‘So! How was your journey? God. It. Is. A. Nightmare getting down here, isn’t it?’

Claire opened her mouth to agree – the trip from London had in fact taken the entire afternoon and a good portion of the evening – but Figgy didn’t wait for an answer. She carried on chatting almost non-stop, while driving with the speed and abandon of someone who thinks they are a very good driver.

The car barrelled through the village of Wilbourne Major along back roads to Wilbourne Duces (an even smaller village that seemed more like a collection of houses around a pub and a postbox), and out into narrow lanes that twisted through fields. Claire found an opening eventually.

‘Who’s going to be here for the weekend, then? If you don’t mind me asking,’ she said.

‘Well,’ replied Figgy, intermittently taking her hands off the wheel to count off on her fingers, ‘it’s going to be almost all the family. There’s Nana, obviously. She’ll be hard to miss, she’s the old lady in the wheelchair. Eighty-four on Sunday! Then there’s Mummy and Daddy – Clementine and Hugh to you, I suppose. My sister-in-law Tuppence is here, too. She’s married to my oldest bro, and brought their kid Alex along. Oh, and Basher’s here, of course. He’s the middle brother and he used to be a proper police detective, but he totally quit after the party last year. Bit of a sore spot with the ’rents, so maybe don’t ask about it. Actually a huge sore spot. Massive drama.’

‘Sorry, did you say “Basher”?’

‘Ye-e-e-s! Sebastian, really, but nobody calls him that. I’m sure you met him. He came to a party at halls once.’ Claire vaguely remembered a grave, blond young man with grey eyes eating all the Chilli Heatwave Doritos at a weekend pre-game before what was definitely not a pub crawl for Figgy’s birthday (because pub crawls were unsanctioned by the uni, ever since a first-year chem student got alcohol poisoning).

‘That’s a load of people,’ said Soph, who always kept track better than Claire. She often had to give Claire name prompts. ‘Especially if more are turning up for the main party tomorrow.’

‘It sounds like heaps, but it’s actually less than last year,’ said Figgy. ‘Is it a problem?’

‘Nah,’ said Claire. ‘I’ve, um, had bigger groups.’ This was in fact untrue, but there was no reason to tell the truth.

‘Gosh, it’s so amazing you could come, you know – you really saved my bacon. Usually we take turns to arrange entertainment for the family get-togethers, and I totally forgot it was my go this time. But when I ran into you, I was just like: Oh. My. God! Perfect for Halloween, you know? You look fabulous, by the way,’ Figgy added, lyingly.

Claire was in the middle of what was turning out to be an indefinitely long lean patch. She was wearing battered trainers with holes in the heels, a pair of black jeans that were so worn through they were grey, and a fifteen-year-old wool coat over her one nice winter jumper, in deference to the fact they were visiting a rich family. Her dyed black hair was showing about three inches of mousy roots, in contrast to Figgy’s perfect white-blonde French plait. Figgy wasn’t totally unkind. This hadn’t stopped Claire asking for a fee about 150 per cent higher than her usual rate, to which Figgy had readily agreed. So readily that Claire realized she should have plumped for 200 per cent.

‘Yeah,’ she said, offering a smile. ‘It should be good. It’s a big old house, right?’

‘Mmm! It has wings. Grade Two listed, because of the library. Of course, really it all belongs to Nana. She keeps joking that she’s going to change her will and have Mummy and Daddy out on their ear. They’ve properly rowed about it a few times, so I hope it doesn’t kick off in front of you. That would be so embarrassing! It’s just, you know, such an expensive old place to run, and I think Nana is worried that Mummy and Daddy are struggling. But honestly, Mummy would rather sell a kidney than that house.’

There was a pause as Figgy changed up a gear, releasing the clutch so abruptly that Claire jerked forward about six inches and heard one of the bags in the back fall off the seat.

‘Whoops! Anyway, you don’t need to worry about all that. It’s a lovely place, really. I think the house is a couple of hundred years old or something. And the land used to have a monastery, so there are some ruined bits of wall and things that are much older. That’s why the house is still officially called The Cloisters.’

‘There’d better not be any grim dead monks hanging about,’ interjected Sophie from the back.

‘There’s supposedly heaps of ghosts,’ said Figgy happily. ‘Including this very creepy monk. Every time there’s a death, he’s meant to appear to the next member of the family who’s going to pop their clogs! Although nobody has ever actually seen him – at least not for hundreds of years. Monty made Tristan dress as the monk and hide in my wardrobe once, though, the beast.’

She gave no explanation of who either Tristan or Monty was. Claire imagined some boisterous cousins who visited every summer to have adventures, like the extremely smug children from The Famous Five. Boys in knee-shorts and long socks who said ‘Rather!’ and drank loads of ginger beer and lemonade to wash down doorstep-sized ham sandwiches.

Figgy suddenly swerved right, onto a neat dirt road that sloped downwards. Unidentifiable trees knotted their arms together overhead. The car began scrunching over gravel, and Claire got a glimpse of an imposing grey stone portico, before Figgy swung around the side of the building and came to a stop at the back. There were lights on here – Figgy explained that the family spent most of their time in and around the old kitchen.

‘All these bits used to be for, you know, looking after the house,’ she said as she got out of the car. ‘Pantries, and rooms for some of the important servants, that sort of thing. It’s been converted into the family home, so the rest of the place can be used for’ – Figgy waved her hands vaguely – ‘weddings and corporate away-days and shooting parties, and so on.’

She led them through a heavy green wooden door, which opened directly into a large room with a flagstoned floor and whitewashed walls. Claire was immediately disorientated by the bright light, the explosion of savoury smells and an assault of loud hooting from the family. It was a kind of wordless, elongated vowel noise in place of an actual greeting, to herald their arrival.

A shorter, squatter, older version of Figgy bustled over, though where Figgy’s skin was a delicate white porcelain colour with perfect blush cheeks, this woman was more bronzed, as if she spent most weekends gardening. She had a perfect feathery blonde bob and a deep pink cardigan with a string of neat pearls hanging around her neck, but she also had a powerful welly-boots aura. This was not just a mum. This was an M&S mum.

‘Hellooooo, dahlings! I’m afraid we couldn’t wait to eat, but there’s plenty left,’ said – presumably – Clementine, giving out air-kisses that left a strong rose-scented perfume in their wake. ‘I’ll make up some plates. Come in, come in! Say hello. Hugh was just going into the other room to watch the rugger.’ Here Clementine gave an exaggerated eyeroll, as if to intimate that they were all girls here – ha, men and their balls!

‘That woman never met a Laura Ashley print she didn’t like,’ said Sophie, talking quietly in Claire’s ear. ‘I bet she has a knitting circle of dearest friends and hates every one of them. I bet she has a plan to kill each of them and get away with it.’

Sophie had a habit of being unkind about people when she first met them (and also after she’d first met them), but in this case Claire had to admit she was right. Clementine had an intensity to her kindness that hinted at a blanket intensity to all her actions.

They paused to look around. The room they were in was clearly the old kitchen, but had been converted to an all-purpose family room. It had a high ceiling hung with bunches of dried flowers and herbs, and was bright and warm. In front of the door where they’d come in were a couple of creaking armchairs, and a much-loved sofa faced a smouldering fire. A sturdy wooden table ran off to the left, taking up almost the whole length of the rest of the room, towards a large blue Aga at the far end. The table still held the remnants of a family meal, as well as a few remnants of family, who were getting up to be introduced.

In contrast to his wife’s crisp consonants, patriarch Hugh’s voice was a kind of Canary Wharf foghorn. It went well with his vigorous handshake and his job ‘in finance’. He had a ruddy complexion, the pinkish-red inflammation of a white man who drank a lot of red wine and ate a lot of red meat. His watery blue eyes squinted out of a once-handsome face that was losing its definition at the edges, like a soft cheese.

‘Hugh looks like a man who never misses an episode of Question Time,’ murmured Sophie, cocking an eyebrow.

Claire bit on the inside of her cheek, and managed to give a non-committal ‘mhmm’ in response to Hugh’s greeting. He was folding up a broadsheet paper. There was a story with the headline ‘I Don’t Care What the Wokerati Say, I Won’t Stop Putting Mayonnaise in My Welsh Rarebit’, and she looked at this in disbelief and confusion for long enough that Hugh noticed.

‘Ridiculous, isn’t it? Can’t do or say anything these days. Corporate political correctness is running amok everywhere, and you can’t even bloody eat food how you want!’ he said, misreading her expression. ‘Now people are complaining that if you make rarebit with mayo, it’s cultural appropriation! Can you believe it?’

Claire considered the best way to answer this.

‘No,’ she said. ‘I cannot believe people are doing that.’ She was aware that: a) she would probably fall into this newspaper’s definition of wokerati; and b) if she was able to conceal this from Hugh like a ratfuck coward, she might be able to get a bonus for good behaviour on top of her already-inflated fee.

‘“Putting some mayo in your Welsh rarebit” sounds like a sex thing anyway,’ commented Soph. ‘Newspaper columnists are all perverts.’

Claire bit the inside of her other cheek. Fortunately, this conversation was rescued by the introduction of a third new family member. Hugh gave an awkward side-arm hug to the newcomer, a woman in her forties. ‘This lovely creature is Tuppence. M’boy Monty, my eldest, had the good sense to tie her down!’

Everything about Tuppence was meek: meek ponytail, a swathe of meek pashminas and layered cottons in various browns, and a meek, limp handshake. Even the cold she appeared to have was meek. She kept mopping her nose with tissues that were overflowing from her sleeves, rather than blowing it once, to have done with it.

But when she said, ‘It really is nice to meet you!’ Claire decided Tuppence was her favourite person in the world. ‘My husband can’t be here this weekend,’ she said, answering a question that Claire had not in fact asked. ‘He and Tristan are working on an important case at their firm.’

‘Er, sorry – who is Tristan?’

Figgy elbowed in and took Claire’s coat. ‘Sorry, should have said, darling. Tris is my youngest bro, youngest of the four of us. He’s an absolute brat, honestly.’

‘They’re both lawyers at Monty’s firm in London,’ said Tuppence. ‘But we’ll have to make do without them this time, I suppose.’

‘Interesting,’ whispered Sophie, close to Claire’s ear. ‘Tuppence actually sounds quite pleased to be rid of Monty. This family is definitely going to turn out to be a mess, I love it. LOL.’

‘Most families are a mess,’ replied Claire, with an apologetic grimace. ‘Uh, I mean… um, organizing events for families, you know – a nightmare.’

To Claire’s surprise, Tuppence covered her mouth at this and looked at the ceiling. ‘As long as we don’t put mayonnaise in the rarebit,’ she said, as she looked back at Claire. Claire couldn’t have sworn to it, but she thought Tuppence might have winked.

That seemed to be all of the family present in the kitchen. Of Nana, Tuppence’s child or the improbable Basher, there was currently no sign. Clementine reappeared, putting down a loaded plate and leading Claire to sit at the table. Sophie stuck her tongue out at the back of Clem’s head and declared that she was going to look around – which meant roaming the house to nose through as much of people’s private lives as possible.

‘So, Claire!’ said Hugh, who had conjured a bottle of wine from nowhere. ‘Last name Voyant, yes? HA!’

Claire loaded an exploratory forkful of pie, as Figgy sat down next to her. ‘Nope. Hendricks. Good one, though.’ This was her polite stock response to a joke she had heard about a million, billion times.

Hugh was struggling manfully with the corkscrew, and Clementine took the bottle without speaking and opened it for him. Her expression was dispassionate.

‘Terribly exciting, though,’ said Clementine, giving a jovial little shrug. ‘Very unusual kind of entertainment to do, you know. I was really interested when Figgy said she’d hired you.’

‘Mhmm. This pie is really great, thank you,’ said Claire, shovelling it down. She was quite hungry because she’d only had a thing of Super Noodles for lunch before she got on the train. In contrast, Figgy was taking small and delicate mouthfuls and savouring each, as if she were a judge on Masterchef.

‘Claire and I were at university together, d’you remember me saying, Mummy?’ said Figgy. ‘And I ran into her and, when she told me her job, I thought it would be so quirky and spooky. I was only saying to Claire in the car, it’s perfect for Halloween. Didn’t I say that, Claire?’

‘Yes, you did. And yeah, this is usually quite a good time of year for me.’

Claire noticed that everyone in the room was sort of hanging around, watching her. It was a strange feeling. She didn’t think they were trying to be rude, but it seemed a bit like they were privy to a rare zoological exhibit. Just as she thought of them as common-or-garden posh dullards, Claire realized that they saw her as the lesser-known drab weirdo. It wasn’t that people didn’t think she was weird quite often, but they were usually more subtle about it; or, having hired her, were more engaged with the weirdness. And she had seen enough horror films to know that a bunch of upper-class people inviting you to their family home for Halloween weekend, and then examining you like some sort of game bird, was a potential recipe for disaster. She looked around, but Sophie was still off exploring.

Perhaps realizing that everyone was staring at Claire in silence, Clementine abruptly announced that there wasn’t a pudding, but there was fruit, which made Hugh grumble under his breath. He sidled off to watch the rugby. Figgy finished eating and started helping her mother to tidy up, which made Claire feel awkward. She concentrated on her plate instead. Her wine glass kept magically refilling as she ate, and soon she was feeling quite hot and sick from all the carbs and alcohol that she had hoofed into her stomach.

As if sensing this, too, Clementine led her away to a neat twin bedroom. Clementine’s powers of observation and/or telepathy were unnerving, but the fact that it was a twin room pleased Claire, because it meant there was enough room for Sophie to keep herself entertained. All the furnishings were cream or white, and the walls and roof were a bit higgledy-piggledy. The walls didn’t join up where you’d expect them to – like something a child had tried to make out of Play-Doh. There was a little en suite shower and toilet, though, which was probably more complex than a Play-Doh house would allow. It was very nice. A lot nicer than her flat in London.

Claire opened the window to cool down and suppress her nausea. She was leaning out, collecting deep lungfuls of clean country air, when she realized it wasn’t as clean as she’d expected. The dense and delicious smell of weed was wafting through the autumn night. Then she caught the sound of quiet talking and, remarkably, Sophie laughing.

It took her a few minutes of self-consciously creeping around cold corridors in the dark, but eventually Claire found a heavy curtain that was concealing a set of French doors. On the other side of these was a discreet patio, with a couple of tables and chairs and one of those big garden wood-burner things.

Sophie was staring into the flames. Next to her, a teenager with blue hair was clutching an asymmetrical black cardigan around themself and holding about two-thirds of a massive joint.

‘All right?’ said the teenager, jerking their head up in greeting. They were a good few inches taller than Sophie, looked maybe a couple of years older – enough to legally buy a pint, at least – and appeared to have shaved stripes into one of their eyebrows. ‘I’m Alex.’

‘Huh, I assumed you were younger. Figgy made it sound as if you’re, like, twelve. Are you -andra or -ander?’

‘Neither. Does it matter?’

‘Nope,’ said Claire.

‘Cool. Don’t tell Granny Clem about the weed.’

Claire thought about this. ‘Er. I won’t if I can have some.’

‘Mutually assured destruction,’ said Alex, whilst breathing out another thick herbal cloud. ‘I like it.’ They passed her the joint and moved away from Sophie to get closer to the fire. Claire took the joint, but exclaimed, ‘Fucking Christ!’ and nearly dropped it when someone else entirely said, ‘You must be Claire.’

Claire leaned over to peer at the other side of the wood-burner. There was a very old lady sitting in a wheelchair, wrapped (as is traditional for little old ladies in wheelchairs) in a couple of tartan blankets. Her eyes were twinkling and she looked very much like she was about to laugh. Leaning on a table near her was a man Claire just about recognized as the Dorito-eater from Figgy’s party years ago. He had shaved all his messy blond hair off, which made him look gaunt and tired.

‘That’s Basher and Nana,’ said Sophie. ‘They’re all right. I like them.’

‘I’m right, aren’t I?’ Nana said. ‘You’re Claire. Figgy’s friend from university.’

‘Yeah, that’s me,’ said Claire. She took a modest hit from the joint and passed it back to Alex. It felt weird smoking weed in front of someone else’s granny – great-granny, even. ‘Um. Basher and I have actually met before.’

‘Hmm,’ said Basher. ‘I think I remember.’

‘Wait, you’re the medium?’ said Alex, suddenly interested. ‘Cool. That’s cool. So you can talk to ghosts then.’

‘Yup.’

‘You really expect us to believe that?’ asked Basher.

‘Erm, no. Not really. Most people don’t, obviously,’ said Claire.

Nana laughed and her eyes twinkled again. ‘Very good answer. She’s got you pegged, Bash, dear.’

‘You don’t look like a medium,’ said Alex, passing the joint again.

Emboldened by the positive reception, Claire took a healthier pull this time and spent a few moments looking up at the sky. It had become a very clear night, and this far from a city she could see all the stars scattered everywhere, like broken glass in a pub car park.

‘I dunno,’ she said after a bit. ‘What are mediums supposed to look like?’

‘Yeah, all right, fair enough. Do you have a – a what-chamacallit. A spirit guide?’

‘Yup, I do.’

Basher snorted at this.

‘I do, though!’ Claire protested.

‘Yes,’ Basher said. ‘I expect he’s some Native American chieftain. Or a poor Victorian shoeshine boy?’

‘No, actually,’ said Claire, who was feeling the effects of what really was very good-quality weed. ‘Ah – nah, I don’t know if I should tell you.’

‘You know you have to now!’ cried Alex.

‘Yeah, g’wan. It’ll freak ’em out,’ said Sophie.

‘Okay, okay. She’s a girl in fact.’

‘Ah yes,’ said Basher. ‘With long dark hair, and she is going to crawl out of the TV?’

‘That’s a whole other thing. That’s a movie – that’s not real. Duh,’ Claire replied.

‘Of course, I apologize. So what is your ghost’s tragic back-story? A Georgian waif who died at Christmas? A poor misfortunate who pined to death in the fifties?’

‘Don’t be boring, Uncle B,’ said Alex. ‘You sound like Dad when you get all smug.’

‘She’s not a Victorian waif,’ said Claire, who was starting to get a bit annoyed by Basher and was keen to prove him wrong. ‘She’s from the noughties. She died when she was seventeen.’

‘Ah, very convenient,’ said Basher. ‘No historical research required with a ghost from your own generation.’

‘Well, joke’s on you, because I studied history, so if I wanted to make up a period-accurate ghost I could. But I don’t need to,’ said Claire. She was trying to freak them out a bit, but it wasn’t really working.

Sophie rolled her eyes.

Claire looked up at the diamond sky again and started laughing. ‘It’s funny – she’s not anything. She’s just normal really.’

‘Am not, weirdo,’ said Sophie. ‘I’m exceptional.’

‘She’s annoying,’ Claire corrected. She looked over the flames at her friend, bright-eyed and smirking, standing in the clothes she had been murdered in. ‘Her name’s Sophie and she’s been eavesdropping on you for, like, half an hour already.’

2

A Quick Bit of Seance

The truth was that Claire was not a very good medium. Her figure was not suited to maxi-dresses, incense made her sneeze and she couldn’t be arsed with smoky eyeshadow. She also wasn’t good at coming up with significant but vague things to say about the afterlife, like ‘Ah, the energies from the Other Side are strong here.’ The only part she was good at was that she could genuinely see and talk to dead people, but as it turned out, that bit was the least important.

When Claire had turned to freelance mediuming on a full-time basis she’d swiftly discovered that nobody ever wants a real seance. Attempts to do genuine ones usually ended in disappointment and bad reviews on Tripadvisor. Really, punters just wanted something they could tell their friends about.

They did not actually want to talk to their dearly departed grandad who, even if he was still hanging around, would be more likely to ask about Tottenham’s form, and complain that they never visited enough when he was alive, than say that he loved them and was happy where he was, in heaven with Jesus and all the angels. In fact the two were mutually exclusive: a ghost could not be both in heaven (or whatever came after dying) and able to have a chat on Earth.

Claire didn’t have an especially scientific mind, but as far as she could tell some people simply stayed hanging around after they died, and that was that. It was usually someone who had regrets, either about how they had lived or how they died. Maybe they didn’t get to say goodbye to their loved ones, or their cupcake business didn’t get as much recognition as they felt it deserved, or one of their family managed to get the standing lamp they’d said they absolutely couldn’t have. If they resolved that – if they realized their family loved them anyway, that their cupcakes weren’t actually that great, or that the standing lamp was fugly – then they would disappear. If not, they just hung around, making the air cold and sometimes moaning at other ghosts (particularly the case in churchyards, where there were usually a few ghosts corralled together, nurturing petty ghost grievances that were the dead person equivalent of a neighbour not returning a borrowed casserole dish, but sharpened to acuteness over hundreds of years). Unless they made an effort to keep their shit literally together, older ghosts could get fuzzy, and eventually became nothing more than a little cloud of misty unhappiness.

That was how it was; that was what Claire had observed. In the extremely online debates about whether a hot dog was a sandwich, Claire would be the sort of person to say that a sandwich was what got put in front of you when you asked for one in a greasy spoon. Evidence suggested that a ghost was a person capable of annoying nobody except, specifically, Claire, and this rendered the metaphysics of the situation more or less a moot point for her.

Over the years, Sophie and Claire had, using a lot of trial and error, developed what were fairly good versions of fake seances, with a bit of real communication with the dead thrown in – which Claire editorialized and expanded upon, if the ghosts weren’t saying anything that interesting or nice. Technically, Claire didn’t need Sophie’s help to talk to ghosts, but the process (which involved Sophie yelling loudly to attract as many spirits as possible) went more smoothly when they worked together. Claire had an advantage over her spiritualist ancestors: cold-reading was pretty easy when everyone shared everything online, plus Sophie was able to have a good nose around their hosts’ houses without anyone knowing.

Their seances were sufficiently skilful now that Claire had a client bench deep enough at least to eat and pay the rent. But she did feel aggrieved that her ability to see and talk to dead people – which was actually a pretty bloody impressive thing to do, when you thought about it – was basically good for nothing. By rights she should be mega-rich and have a syndicated television show. But she wasn’t and she didn’t, and even if someone offered her a TV gig, she would get scared and turn it down, partly for reasons she didn’t like to talk about which had left her afraid of public exposure, but also because she didn’t have the natural confidence around people that Sophie did. Sometimes, in very quiet moments at two o’clock in the morning, Claire wondered if it would have been better if she had died and become the ghost. Sophie would probably have had a recurring guest spot on This Morning by now. All Claire had was this gig at Figgy’s parents’ weird old house.

And she was possibly jeopardizing even that by chuckling like a gibbon after describing how a girl had died at seventeen and was now her invisible companion.

‘Sorry, sorry,’ she said, getting herself under control. ‘It’s just funny that you’re saying she doesn’t exist, when she’s right there.’

Alex, Basher and Nana looked, variously, alarmed, incredulous and sympathetic.

‘Seventeen! That’s no age,’ said Nana. ‘I’m sorry to hear that, Sophie dear.’ She looked towards where she assumed Sophie was standing, and Sophie obligingly moved so that she wasn’t wrong. ‘Did you two know each other when you were alive?’

‘No-o-o. No. Nope,’ said Claire. She had learned from experience that people didn’t respond well to her spirit guide being her best friend from school, a real person whose memory Claire was – to the outside observer –exploiting for money. ‘We would have been born around the same time, but that’s it. Never knew her. She just, uh, turned up one day. It was when I was a teenager, too, so we suspect it was something to do with hormones and, er, moon energies.’

Sophie grimaced. ‘You know, I still hate it that that line actually works on people.’

‘A bit like the X-Men,’ said Alex, snickering. ‘In the films a lot of them got powers around the age of sexual maturity. Is seeing ghosts also a metaphor, do you think?’

‘I think I understand that. I got a lot of stretchmarks when I turned sixteen. I grew about a foot overnight, I remember,’ said Nana.

‘Oh, come on, Nana. You don’t seriously believe any of this is true?’ said Basher, who seemed to be getting annoyed. He would be the useful sceptic, Claire could already tell. ‘Not the stretchmarks. The talking to ghosts.’

‘Well, I’m very nearly dead, dear, and you’re talking to me,’ Nana said.

‘Before you arrived,’ Sophie told Claire, ‘they were talking about how the family should just sell the house to a hotel chain that’s sniffing around. Du-something. Du Lotte Hotels, I think.’ Claire repeated this.

‘That doesn’t prove anything!’ said Basher, his eyes flashing in the firelight. ‘You probably heard that yourself. And by the way, it’s bloody rude to listen in to private conversations.’

Sophie moved around to blow on his neck idly and make him shiver, and giggled when he did.

‘That’s her. She’s blowing on your neck.’

‘Give over. It’s cold out here – I am cold.’

Sophie next started tickling the side of Nana’s face. Nana raised a hand to her cheek.

‘Yeah, that’s her,’ said Claire, before Nana could ask. ‘She’s tickling your face.’ Claire elaborated, explaining: Sophie wasn’t a poltergeist, she couldn’t pick things up or rifle through your knicker drawer, but if you’d left your knicker drawer open or a private letter out somewhere, she’d have a proper good look. She’d been naturally nosy even before she’d died; being invisible only made it easier. If she blew on your face, it felt like you were looking into a freezer; and if she tickled your cheek, you might think a cold spider was walking across it. But that was all she could do, unless she was getting help from Claire.

‘That’s jolly interesting, isn’t it?’ said Nana. ‘Do you know, I’m quite looking forward to dying now. I’m sure ghosts don’t get swollen feet.’

‘First of all,’ said Basher, ‘can we stop talking as if you’re going to shuffle off your mortal coil tomorrow morning? And, second, have we just accepted the existence of ghosts now? Is that all it took?’

Alex shrugged and carefully put out the joint. ‘We should do a seance. Can we do a seance? I’ve never done one before, I wanna do one.’

‘Doing one tomorrow night. S’what I’m here for. What we’re here for. When all the other guests have arrived. Midnight seance: bell, book and candle, the whole thing. Well spooky. Proper seance business.’

‘I mean we should do one tonight. Now.’

Claire looked over at Sophie.

‘I don’t care if we do one now,’ Sophie said. ‘Figgy was right: there are a load of deados hanging around, for me to drum up for conversation. An old lady was having a blazing row with a little Frenchman in one of the rooms in the big house. Also a pervy old gardener, like, you know, a really shit version of Sean Bean in that TV series about a woman shagging her gamekeeper. On the other hand, they seem quite boring, they might not turn up, and you’re pissed and also high, so I dunno if you’ll be much use at cold-reading, if the ghosts are rubbish. It’s a gamble. But one I’m willing for you to take. LOL.’

Alex misinterpreted the long pause while Claire listened to Soph, because they tipped their head on one side and said, ‘I’ll pay you extra, if that’s what you’re worried about. Half fee on top again, right? Exclusive preview for the family, which all our horrible godparents and Grandad Hugh’s mates from work don’t get when they turn up tomorrow.’

Claire had not been worried about getting paid extra, and then worried that she hadn’t worried about it, because that meant she really was quite high.

‘That means,’ added Basher with a slight smile, ‘Alex is going to persuade someone else to pay you extra.’

‘Potato, potahto’s rich lawyer dad,’ said Alex, flapping their hand impatiently.

Claire opened her mouth to object, then shut it again, and Alex took advantage of this indecision. They bundled her back inside and into the kitchen, and before long had convinced Clementine and Figgy that they could have what Clementine called ‘a quick bit of seance’ before bed, as long as Nana didn’t get too worked up. They went to crowbar Hugh from his game (‘For heaven’s sake, it’s a recording, Hugh! You can just pause it!’) and Claire went to her room to try and prepare as best she could.

She filled the sink with cold water and stuck her face into it, while Sophie lay on one of the beds and watched.

‘You’re such a train wreck. You haven’t done one of these while you’re pissed since like, what… 2013? This is going to go terribly – it’s going to be amazing.’

‘“Bit of seance”,’ Claire muttered. ‘It’s not a sugar-free fizzy drink. You can’t do a… a fucking “seance lite”. Christ, I hate rich people.’

‘You know, I’m not even sure they’re that rich, really,’ said Soph, thinking out loud. ‘I mean obviously they are, in a relative sense, but if you look around at this place, you start to notice all the bits where it’s falling apart.’ She pointed out cracks in the plaster around the window, and patches of rot in the wooden frame itself.

Sophie was much better at noticing things. All she did now was watch, of course, but she had watched when she was alive, too. She had noticed, for example, the introverted, mousy girl nervously waiting alone at the bus stop on the first day of Big School at the turn of the millennium, and although Soph had been alone as well, she had not been nervous. It was an emotion that was beyond her, even aged eleven. She had gone up to Claire and said, ‘Hello. Let’s be friends.’ And so they were. Claire had never been sure why she’d been chosen, but it had happened. And Sophie was pretty, and knew how to plait her hair and do make-up, and already shaved her legs, and pretended not to try in class, even though she secretly did. Her association threw a shield around Claire, who suspected she would otherwise have been consigned to the weirdo kids who wore bow ties and wrote poetry at lunchtime.

In return, Claire helped Sophie with homework –which was the sort of thing Sophie never had the patience for – and made her laugh, and bared her secret innermost thoughts and listened to Sophie’s, and drank blue WKD in a field until they were sick, and swung on children’s swings on frosty nights until they went so high that Claire was afraid of what would happen if they fell.

Soph was never afraid. She would always have kept going.

As they got older, Sophie decided her favourite drink was Bacardi, and that was what she was like, too: strong, sweet, clear, overwhelming. (Claire was rosé wine, something a bit childish masquerading as almost adult.)

When Sophie vanished, Claire had lost touch with who she was as a person. The disappearance had given her, by association, a layer of grim, Gothic mystique. The missing girl’s best friend! The enfant tragique! But after a while everyone had tired of that and had dropped Claire, for her rapidly increasing strangeness: the talking to herself, the covering her ears to block out inaudible sounds, the wearing of layers and layers of clothes even indoors, and then the eventual embracing of the cold. Because Sophie had come back. Like she had chosen Claire all over again. Sophie was the first friend Claire had, and the first ghost she saw. After she returned, Claire saw dead people everywhere.

Secretly she had been relieved at Sophie’s return – even in her ghostly state. But lately, although she’d never share the thought, Claire had begun to wonder how much she and Sophie really had in common, apart from the fact that they’d been friends for so long. Perhaps, under normal circumstances, their friendship would not have survived the test of adulthood. Luckily – or, technically unluckily, she supposed – any testing was now moot. They were stuck together. Almost literally, because unlike most ghosts who were tethered to a place, Sophie was tethered to Claire, and when they got far enough apart Claire could feel it like tension on a lead.

Worse, perhaps, was that Sophie was stuck as a person, too: she had the lifetime of experience of an adult, but assessed it like a teen. She was quick to anger, quick to invent and point out injustices, as swift and as casual in her insults as she had been when part of a tribe of adolescents, picking sides and drawing battle lines at house-parties and pubs. More and more, Claire worried that she herself was the same. Perhaps she had never got rid of her worst, most immature impulses because they were given voice and form every day. They were there when she woke up and when she got into bed, and they watched her while she dreamed.

*

Left alone in her guest bedroom, Claire changed into what she thought of as her work clothes: a sober black dress and, retrieved reverentially from a plastic baggy that years ago had held a small quantity of terrible cheap cocaine that was later snorted off a toilet in a student union bar, one of Sophie’s real-life butterfly hair-claws. Claire carefully fixed it into her own hair, pinning back the wonky bit of her fringe left from where she’d tried to trim it herself. Then she gathered her equipment: a big brass hand-bell, a heavy silver candlestick with impressive wax dribbles, a plastic Bic lighter and a large, old Bible.

The main house would normally have been hosting guests or some kind of event, but was kept free on birthday weekends so that the Wellington-Forges could pretend it was still all theirs. That they had the run of the whole place and bossed servants about, like their ancestors used to. The bit of seance was going to be held in the library, an impressive room with floor-to-ceiling shelves on one wall, full of leather-bound books with gold-printed spines: bottle-green, wine-red, earthy brown tomes. Opposite these was a bank of huge leaded-glass windows.

The clouds peeled back from the moon outside, and the room was filled with little diamonds of black and white. Claire felt her skin tingle, like she was being watched. She breathed in and, instead of the dry air of a room full of books, she tasted mud in the back of her throat. Her heart rate spiked in sudden panic and she was struck with a wave of fear and nausea – a nausea distinct from the churning red wine sickness she already felt. Sharp pain flashed behind her eyes and she groped for the back of a chair to lean on.

There was a sudden rattle as Figgy started to pull the curtains shut, and Clementine switched a lamp on. The moment was over, and nobody seemed to have noticed. Claire looked at Sophie, who nodded grimly.

‘I felt it too,’ she said. ‘I’ll keep an eye out for any buzz kills.’ Some spirits stayed bitter. The mean ones did try to ruin things sometimes.

The family were arranged around a large round table. Nana patted a seat between her and Basher. Claire went over, placed the candle and book in front of her, then bent to put the bell under the table in a slow, exaggerated fashion.

‘Hold on,’ said Basher, on cue. ‘I read about this. Houdini showed how you can just ring the bell with your foot and we wouldn’t know.’

Claire tried not to smile. She could always count on one person knowing about Houdini. ‘Of course,’ she said and put the bell in the middle of the table. She nodded to herself, turned the lamp off and then regretted the order in which she’d done things, as she blundered back to the table in darkness to light the candle.

The room narrowed to a point as the darkness became darker. As if they knew what was expected of them, everyone took the hands of the people on either side of them.

Sophie knelt in the centre of the table, her pale face illuminated from below by the flame. She crawled forward until she was on top of it, and the candle burned inside her. Everyone else saw the candle begin to burn blue at the edges and throw strange, refracted shadows that danced on the ceiling and walls where they had no business being. Claire saw her friend glowing like a paper lantern. She saw the pink hair-claw that she now wore mirrored in Sophie’s hair, the ghost of a hair-clip. It was here, but also there. It was in two places at once. This always made her feel weird.

Claire leaned forward and bowed her head, and Sophie reached out and put her hand on top of it. It was like someone had plonked a bag of frozen peas on the crown of Claire’s head, and she couldn’t help shivering. She felt the zip of the connection between them, like she was a battery pack and Sophie was an iPhone that had just been plugged in. She fought the urge to yawn.

‘Line!’ said Soph.

‘Mmm? Wzt?’

‘It’s your line, weirdo. “Sophie, spirit guide, lost souls of this place, yadda-yadda, and so on.” You are useless.’

Claire stifled a burp. ‘S-Sophie. My spirit guide. Please – ugh – please connect us to the lost souls of this place. Help us speak with them. Is there anybody there?’

Sophie reached in front of her and, by using Claire’s strength, was able to lift the bell about half an inch. She began ringing it gently, but rhythmically. Claire was pleased to hear several gasps from around the table. They would have been less impressed by the mystic forces at work if they could hear Sophie’s yelling: ‘COME ON THEN! BRING OUT YER DEAD! LET’S GO! TALKING TO THE LIVING, RIGHT HERE! ROLL UP, ROLL UP –I’VE NOT GOT ALL FUCKING NIGHT.’

A few foggy shapes began to seep through the walls –the really old dead, who couldn’t remember who or what they were any more. Only one ghost who turned up still looked like a person: an elderly white man with a green flat cap, a big white moustache and yellow corduroy trousers. He was leaning on a pitchfork.

‘Here,’ he said, in a strong Cornish accent. ‘Can us really talk to them? Ask about the girl who visited last year. Where’s she to? She had a cracking pair of—’

‘Ohmigod, shutthefuckup, you old perv! I think he’s your lot tonight, to be honest,’ Sophie told Claire, apologetically. ‘Go with an old standby. I haven’t discovered anything properly juicy yet.’

They fumbled through a few cold-reads, based on family photos that Sophie described, and the people round the table were more or less impressed by the whole thing (mostly less, if Claire was being honest with herself). Sophie kept laughing and suggesting she reveal that Tuppence was going to cheat on Monty and abscond to the Lake District with her lover and all the family’s money. Getting desperate, Claire tried intimating that Clementine’s father gave the family their blessing to sell the house, which went down extremely poorly. Basher’s hand tightened angrily in her own. But at that point the old gardener, who was still hanging around, got bored. He hobbled forward and grabbed Sophie’s ankle with an experimental air. Claire felt another zip as the drain on her doubled, and then a ghostly argument rang out across the silent room, for everyone to hear.

‘How does this work? Tell them we don’t like all the young lads who comes here and has big parties and pisses in the rose garden. Ruins the soil.’

‘Ohmigod, let go, that is so rude!’

Claire craned to try and see what was happening, because no ghost had done this to Sophie before. None of the family around the table had leapt from their seat in alarm, so she was fairly sure the ghosts weren’t visible to anyone else, but the old man was definitely pulling energy from her through Sophie, because she could feel herself getting more tired by the second.

Claire could just about see that Hugh and Clementine, off to her left, were looking around to try to locate the source of the voices. Normally dead people sounded sort of two-dimensional – not without emotion, but flat, appearing in Claire’s ears without bumping into any air in between. It was hard to tell, but now it was as if someone had turned on an invisible speaker above the table, so that Sophie’s and the gardener’s voices were being pumped into the room, echoing off the walls, crossing over one another and wavering in volume.

‘Also, please tell Her Majesty congratulations on the birth of her son. I would have written, but I couldn’t, on account of being dead.’

‘Okay, well, you could mean literally, like, three different people by that, so I don’t know—’

‘You button up, young lady. Trouble is that young people like you got no respect for their elders, so you just let me talk—’

‘Claire, this grotey old perv won’t let go of my foot.’

Nana started laughing.

‘Well! Is that Miss Janey?’ asked the gardener, ignoring Sophie’s attempts to kick him off her. ‘You know, I always took an interest in you – a very particular interest. Bright as a button you were.’

‘Hello, Ted! I’m glad you still seem to be in good form. For a dead man,’ said Nana.

‘Ar, good form, Miss Janey, good form.’ Ted was starting to look alarmingly solid.

Claire felt light-headed. Basher was leaning forward.

‘And may I say you looked beautiful on your wedding day. You were a fine girl and, if I may add, meaning no disrespect, you grew up into a very fine young woman—’

Sophie shrieking ‘Ohmigod, put a fucking cork in it, Ted!’ was the last thing the party heard, before Claire jerked her head back from Sophie’s reach. It was like unplugging a really strange and specific radio. But she could still see and hear the ghosts. Sophie was kicking at Ted while he cackled heartily.

‘The, uh, the circle is broken, or whatever,’ said Claire vaguely. She blew out the candle. The darkness was reassuringly normal and gave her a few moments of cover to slump back in the chair. She would say it felt as if she’d just run a marathon – if she had ever done any recreational running whatsoever.

Around her she could hear the Wellington-Forges reacting. Figgy was doing happy piglet squeals, enjoying being scared in a safe way. Hugh kept rumbling, ‘Very good. Bloody good, I thought.’ Nana was humming. Clementine immediately began bustling, and soon had the lights on again. This revealed that Alex was on their hands and knees under the table, and Basher was pulling large books off a shelf at random.

Alex poked their head out and looked up at Claire, unabashed. ‘No wires,’ they said, with a grin.

‘That does not rule out wireless technology,’ said Basher. He continued feeling along the shelves and checking books.

‘Ah,’ said Claire. ‘You’re, er, looking for a speaker.’ At least she tried to say this, but the word ‘speaker’ disappeared into a yawn.

‘You should go to bed,’ said Sophie. ‘This idiot properly wiped you out. Could have hurt you. D’you hear me? Look at her.’ She glared at Ted, who took his cap off and wrung it in his hands in such a cartoonishly subservient way that it looped round into sarcasm. He walked out into the garden through the wall.

‘Well now, that was fun!’ said Clementine. ‘But you look tired, darling. Don’t let us keep you up before the big day tomorrow! And you too, Mum,’ she added, turning to Nana.

‘Yes, I do think it’s time for me to turn in,’ agreed Nana. ‘I’ll be up past my bedtime tomorrow, too!’

They all started to troop out of the room. Claire thought she was last out and pulled the door almost to behind her, but then Soph gave her a nudge. ‘Here, look,’ she said and pointed back into the library. Claire peered around the door.

Basher had lingered and was standing by the table. He looked around and, satisfied that nobody was watching, waved a hand cautiously through the air where Ted the gardener had been standing during the seance. Then he sighed and seemed to sort of pull himself together. Claire hurried away before he spotted her.

Nana insisted that Claire escort her to bed, although Basher caught up and followed them suspiciously.

‘Ted was the gardener here when I was little,’ Nana said. ‘He died in the middle of turning over potatoes. How extraordinary!’

Claire helped her into bed, while Sophie sat on the end of it, looking at her. Nana had hair like very fine silvery cobwebs, and her skin had shrunk close to her bones, which felt light and breakable like fine china. Claire looked at the veins on the backs of her hands and saw that Nana had very bad arthritis, too. She must be in quite a lot of pain all the time, but didn’t show any sign of it. And her eyes, stormy and grey, flashed quick with intelligence. Nothing got past Nana.

‘I’m so pleased we’ll be doing another one of those tomorrow, dear. That was fantastic! Don’t you think so, Basher?’

‘Hmm. Yes, fantastic. Unbelievable, one might say,’ said Basher, hardly dripping with sincerity. ‘But you should get some sleep now, Nana. You have your party tomorrow.’

‘Yes, yes. Because, apparently, I won’t sleep when I’m dead! Ha-ha!’

‘I don’t think Nana will become a ghost,’ said Sophie. ‘She’s too content. She seems quite ready to go. Whenever it happens.’

Claire relayed this, and Nana agreed.

‘I do wish, though,’ she said, ‘that I had sold this place when I had the chance. I kept trying to arrange it, and Clemmy kept putting me off. “The estate agent people couldn’t come today” – that sort of thing. It’s a millstone in this day and age, you know, a big place like this. Well, I still have time to get it done. I’m going to really push for it. It’s still my house, after all.’

Basher carefully tucked his nana in and she snuggled down into the pillows. As she was leaving, Nana grabbed Claire’s hand. ‘You’re a nice girl, Claire. Let’s talk more tomorrow.’

Basher helped Claire find her way back to her room, which she was happy about because the corridors all looked the same to her. At one point she tried to open the wrong door, and Basher steered her away, one hand on her elbow. His fingers were long and fine, and his grip was firm but careful – gentle.

‘Um. Thank you,’ she said.