Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

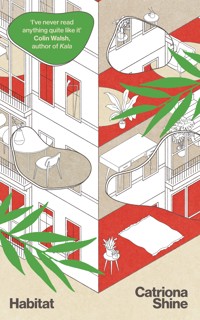

Habitat follows seven neighbours over the course of a surreal and life-changing week as their mid-century apartment building in Oslo begins to inexplicably break down around them. Connected by familial ties, long acquaintance, simmering feuds and longing glimpses, the residents of the building are bound to one another in more ways than they know. As each inhabitant is touched by strange and sinister phenomena, and their apartment-sized worlds begin to fray at the seams, they struggle to grasp that this is a shared crisis that cannot be borne alone. This remarkable debut novel from one of Ireland's most promising emerging talents is a startling parable of our uncertain age, as well as a beautiful and inciteful examination of how we deal with seismic events beyond our comprehension and how we can only truly find meaning through shared understanding. 'In this unsettling contemporary fable, which is a brilliant analogy for our collective apathy in the face of environmental destruction, Shine depicts a disparate group of characters, each of whom is isolated in their struggle to manage impending chaos in an apartment block in Oslo. Lucid and uncanny, the story lingers long in the mind.' Cathy Sweeney 'Truly uncanny – a novel that marries the cosmic nightmare of Darren Aronofsky's Mother! with the sociological portraits of Ken Loach. Chapter by chapter, in the face of forces that are undeniable and elemental, Habitat's domesticated world of rules and regulations deforms itself into something unsettling and eerily recognisable. I've never read anything quite like it.' Colin Walsh 'Shine's gaze is fresh, observant and unsettling. Habitat is an inventive and compelling read, a remarkable debut from an immensely talented writer.' Danielle McLaughlin 'Habitat is an uncanny fable of, and for, a disintegrating world – a bold and strikingly original debut from a sophisticated new voice in Irish fiction.' Lucy Caldwell

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 417

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Habitat

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to the Arts Council for their financial support; to my editor Seán Farrell and everyone at the Lilliput Press for their precision, care and ambition with this novel; to Jo Minogue for reading early on; to fellow writers for ongoing discussions.

Habitat

Catriona Shine

THE LILLIPUT PRESS DUBLIN

First published in 2024 by

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

62–63 Sitric Road, Arbour Hill,

Dublin 7, Ireland

www.lilliputpress.ie

Copyright © Catriona Shine, 2024

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the publisher.

A CIP record for this title is available from The British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ISBN 978 1 84351 8877

eBook ISBN 978 1 84351 9010

Set in 12.5pt on 17pt Fournier MT Std by Compuscript Printed in Sweden by ScandBook

Monday

We settled slowly from bones and shells. Our particles pressed down on one another. There are deep troughs in coastal woods where our skeletal grains once lay. Descended from rock, we are also a careful proportion of clay. We were pulverized, heated to the point of vitrification, fused. We were then ground down once more. Part stone and part sand; water was once mixed into our dust. Poured into moulds, we set, gripping rods of steel. It is this clinging that keeps us in place, where you set us, far enough apart, one above the other, so that you can walk between us without knocking your skulls. We cling, but it is you who fear, who must be kept apart from members of your species who are not your family. We rest our edges on walls of bricks, transferring our load, the load of you and your possessions. You have no plan for us after this. Your thoughts will crumble with us.

Knut

Knut and his grandson woke to one another’s noises and met in the hallway. Knut bent over, with the intention of planting a kiss on Teddy’s head, but, feeling a pull under his right shoulder blade, he contented himself with ruffling the boy’s hair.

Good morning, little prince, he said. Where’s Mamma?

Teddy pointed in the direction of the bedroom.

The door was held open by Teddy’s trailing blanket. Knut edged the blanket back in and closed the door with only the faintest click of the handle. This had been his own room as a child, and he knew from the deep snug inside him that Bibbi would be safe there. He could not even feel guilty for letting his own mother move out to make room for them. This way, they could stay close.

Knut put a finger to his lips.

Let Mamma and Granny sleep, he said.

Bibbi had slept like a log the past week and, if she did, she needed it. Her marriage to that executive should never have gone ahead at all, if you asked Knut. But no one did, and if anyone had asked him, if Bibbi herself had asked him at the time, he would have said, What do I know? It’s your own choice.

Still, it was hard to regret it all when little Teddy was there, making music with marbles on the floor. Only a completely useless father would abandon his own son outright, but it was a good thing, for Bibbi, that he was gone. He made no marks, but that man had left a trace on her. Being an attractive young woman brought as much trouble as good. Knut worried about how often she went out at night ever since she came back. Staying in touch with friends, she called it, but before he knew it she would have a new partner. It never seemed to take long. Then she would be gone again, along with Teddy this time.

Apissu, apissu, all fall down, said Teddy.

Knut didn’t mind getting up in the morning anymore. Teddy’s little voice did something to him. It was like a breeze which blew his eyes wide open, a string which pulled him up to standing. Still, to appreciate Teddy fully at such an early hour of the morning, he needed a cup of black coffee in his hand. In the kitchen, he spooned ground coffee into the filter bag, added water and turned on the Moccamaster. He heard marbles rolling along the wooden floor as he measured out oats and milk. Enough for two, because Teddy ate like a man. He snuck out one cup of coffee before the brew had finished and heard Teddy saying, Ball, ball, with increasing frustration.

Knut turned on the wall lamp in the hallway.

There, he said, will we have some porridge?

Ball, said Teddy.

He had managed to pull Une’s knitted jacket from the coat stand and was, with some success, removing the spherical buttons.

No, no, no, Teddy, they are Granny’s buttons, you see? Buttons. What have you done with your marbles?

Ball, said Teddy, and Knut decided that the harm was done and there was no point in waking the others with the child’s screams, which were sure to erupt if he took away the jacket without a replacement.

Where are the little coloured balls? he said.

It was with considerable difficulty he got down on his knees and felt along the skirting boards, around the mat and under the hall stand.

What did you do with the lovely small balls? he said, getting a bit worried now. He could hear the porridge spitting, needing to be stirred and turned down.

You didn’t eat them, did you? We don’t eat small balls, do we?

Gone, said Teddy, his palms raised in proof.

Knut put two fingers into the boy’s mouth and felt along the inside of his chubby cheeks – huge muscles – as Teddy squealed.

Say ah, he said, and then the screaming started.

Bibbi appeared, bleary eyed.

What happened?

I think he swallowed a marble.

Who gave him marbles? He’s only just turned three, Dad. Did you give him marbles? Teddy, say ah.

Ball, said Teddy.

He found them himself, said Knut. They’re from the game of solitaire. I’m surprised he could reach them.

Of course he could!

I can’t find any, Bibbi. He had them just now. He must have hidden them. He can’t have swallowed them all. It’s not humanly possible.

He put his ear against Teddy’s round belly, listened for clinking, and Teddy patted his bald patch like a drum.

Bibbi had the wooden solitaire board in her hands.

Nine – no: six, twelve, eighteen, twenty-four, she said. There were thirty-three of them, I think, no thirty-two.

We’ll find them and count them, said Knut. Teddy, where are all the little balls hiding?

Teddy pulled at the buttons on Une’s jacket, and Une came out in her dressing gown.

The porridge is burning, she said, and look what he’s doing to my jacket.

We think he ate the marbles, said Bibbi. All of them, said Knut.

It’s not possible, said Une, taking the game of solitaire from Bibbi. Knut, you can’t let him out of your sight. We’ll have to bring him to the A&E.

I’m sure he hid them, said Knut. I was only in the kitchen for a few minutes.

Bibbi and I will go, said Une. Let me just get dressed, and you can search, Knut. Ring us if you find them, all right?

Linda

Flink had been pawing the balustrade at the French windows for a good hour. He stood upright like a trapped human with his forepaws as high as they could go on the steel banisters, his wiry tail pivoting between ginger hind legs. Linda stayed in bed. She didn’t think he had it in him to scramble up.

He teetered a moment with all four paws on the top rail, before flinging himself into the bushes below.

The hurried struggle to the window set Linda’s old head reeling. The railing pressed against her lower ribs and loose flakes of rust-backed paint clung to her nightdress, black on white.

It had been a sultry night for early May, reminding her of that summer a lifetime ago when Leif gave her his first gift, a folding fan, and she kept it tucked into the waist strap of her apron.

She always slept with the bedroom window open: a small gap in the winter and open wide in the summer. Up in her top-floor apartment across the way, that had always been fine. She could see her old home from where she stood. Knut and his family would still be in bed. Her bedroom up there opened onto the roof terrace via a pair of French windows just like these.

Down here, she lived like an insect. She felt she might be trampled on, and there was always someone looking in.

The other problem, of course, was the dog, little Flink, who had spent his entire life up on the fourth floor, where he could wander freely out to the terrace.

It was Leif who found Flink, brought him in one Saturday morning while Linda was scrubbing a buttery grit of mackerel skin off the pan. He was uncharacteristically quiet coming in, so Linda rushed out to him without taking the time to dry her hands on the tea towel. She was dripping water on the floor, and there was Leif with a cardboard box in his hands and Flink’s tiny puppy head sticking out. Flink was ginger, like Leif himself, and Linda fell instantly in love.

Leif! she’d scolded, because he was always springing surprises on her. She never admitted how much she liked it.

She repeated his name aloud now: Leif, Leif. She had read somewhere that we die our final death the last time we are remembered.

Flink was almost twenty years old now, on his last legs. That’s probably what they said about her. That architect couple – what were they called? – Frida and Fritjof, yes. They always waltzed past her with a hasty hello when they came down to walk their own dog. Perhaps they thought Flink was too old to sniff Rocky’s rump, or that he wouldn’t be able to reach, or that Linda couldn’t keep up if they walked together.

Flink was running around the rectangular pond, whose fountain was turned off this early in the morning. That awful Hildegunn’s silver cat was stalking the back garden for small birds. It was that idiot cat who drew her own Flink outside, though how the slinky feline managed to descend from the third floor, Linda couldn’t say. There was nothing to climb down, unless it hopped from one balcony to the next – a difficult task, since they were directly over one another.

The cat jumped out of the rose bushes, up onto the edge of a garden-level balcony. It slipped in under the wired glass balustrade by way of a tiny gap no animal should fit through. It was all fur, no substance.

For over half a century, Linda had lived with Hildegunn underneath her, hating her. Now she had nothing but a basement under her, crammed full of outdated possessions that would be difficult to get to if anyone remembered they existed. It was only when she moved here that she realized she had always walked across her old floor with unease. Of course Hildegunn had hated her after the affair – Hildegunn was the injured party – but she had already hated Linda before that, out of prejudice. The floor was fairly soundproof, but Linda had always left a room if she noticed a noise right below her. Blame rose, seeped through the painted ceiling, the concrete slab and the wooden floor, and it chased Linda’s heels all day. She had Hildegunn to thank that she had been so active all her later years, never sitting still, rising early, going out cycling.

There was a movement at the window directly opposite hers and – Bibbi, she thought, could that be you? She wondered what her poor granddaughter could be doing down there at this hour of the morning. Bibbi might be having an affair with whoever lived there, but then she realized that, no, old eyes deceive – it was only her worry that brought Bibbi to mind – and the person she saw was that quiet young woman she used to chat to when she lived over there. What was her name again? Solveig. No: Mette. No, of course, it was Sonja, like the queen.

Linda used to spy on birds on her terrace and compare notes on her sightings with Sonja. Now they had the same angle on birds, so there was no point in comparing. They lacked an excuse to talk, as well as the opportunity.

Sonja, like the queen: Linda tagged everyone’s name like this now. In her old head, everything worth remembering was still there, but the doors were sometimes locked, and the hinges creaked. She called her granddaughter Baby-Bibbi, though she had her own baby now. That girl had depths, dark and murky, that called to her, ever since her year in London. There were meanings behind Knut and Une’s silences whenever she brought it up. They didn’t want to upset Linda, to agitate her. They thought upset and agitation were fatal to old people.

Flink!

There was no puff in her whisper. The word got barely past her lips. If she called out in earnest, her old voice would fly, ricocheting back and forth between the buildings. She saw Flink in the rose bushes from which the cat had leapt. Poor Flink had not the agility to follow it further.

The earth outside was a good metre below the floor at her feet. Add to that the safety balustrade, and she was certain that Flink would not come back this way. When you were old like her and Flink, you had to go the long way round. She reached out her hand in a stay-where-you-are-boy gesture and pulled back inside, pushing the French windows closed. This was an awkward enough manoeuvre in itself: she had to hold two latches open, one high up and one down low, as she slammed the frame. It banged right into her elbow joints, but it wouldn’t shut. In the warmth and humidity of this tropical night, the window, she presumed, had expanded and no longer fit into its frame.

Linda had known many a sultry night up in her old apartment, but this had never happened to the windows there. It must be the height that made a difference. Up on the fourth floor, the breeze sped past, unhindered, cooling. Down here at garden level, draughts seeped, plants sweated and the air was almost a liquid. She had sunk too low. She had gone underwater.

The back garden was full of honeyed light when Linda came out, and the birds in the big bush were going crazy. Some sort of delirium washed over those small brown balls of feathers at dawn. Every morning, without fail, off they went, equally surprised each time. Was that what they meant when they called you a birdbrain? She heard them more intensely these days, from her bush-level bedroom. She lived with the birds now, though she was further from the sky. Sometimes she wondered if it would be better to start going deaf. The peace of old age.

There was a movement in the bushes at the other end of the garden that had something of Flink’s swagger in it, so she walked in that direction and allowed herself to click her tongue to call him. Surely that couldn’t wake anyone; surely that was quieter than the dawn chorus.

Flink’s tail was sticking out of a bush, wagging so the leaves made the sound of plastic. She clicked her tongue again and he came out. The bushes caught her attention because it was the wrong time of year for berries. Bending down, she saw that the leaves were covered with hundreds of ladybirds. It must be a year for greenfly. She picked one up and let it crawl along her palm. She would need her reading glasses to count its spots. As she hooked the leash onto Flink’s collar, the ladybird spread its red-armour wings and flew back to gorge itself green.

She heard a child crying not far away and thought of Bibbi, of Teddy.

Sonja

Sonja woke in the twittering dawn. A breeze rubbed over the hairs on her calf, tickling them upright. She tucked the edges of the duvet underneath her, so there was no flow of air into or out of her upholstered bubble. A strand of out-grown fringe blew over her eyelid.

For heaven’s sake, she said.

She toed her slippers the right way and went to the French windows. The whole long winter it was fine and now, in the month of May, on this most critical of nights, air decided to leak in. She pushed the curtains aside and felt along the edge of the window to locate the gap, but she felt no draught.

Across the way, Linda, her elderly counterpart in the opposite block, was also awake, standing at her wide-open window in only a nightdress. This selfless old woman had moved from the big top-floor apartment three floors above Sonja last month so her son, Knut, and his family could move in. Sonja missed having Linda in her own block, missed being waylaid on her way in or out to chat about birds in the old days, the original gardener or who had said what about whom in the gardening committee. She saw Linda more often now, out on her balcony, but they were too far apart to speak.

She still had Hildegunn to chat to, the second eldest resident, but the two old ladies were arch-enemies, so it felt like a minor betrayal. Hildegunn had lived directly under Linda for decades and claimed to know everything there was to know about her neighbour. Hildegunn once told Sonja, in hushed tones, that Linda was nothing more than a maid. She had moved into the building when it was newly built, when she was only fifteen, and, soon after, had married her employer. That woman had married into the building, and there she sat, in the best apartment, like a queen bee all these years. According to Hildegunn, a tramp was a tramp, no matter where they lived.

Linda was leaning over her railing now, a hand out-stretched towards the swaying branch of a hibiscus bush. It was clearly out of reach. Sonja marvelled at the gnarled directionlessness of the ancient arm. She wanted to sketch that branchy limb.

Though Sonja was behind two layers of glass, she must have made some sudden movement, as Linda’s smoky gaze flicked across to her. Sonja’s hand went up in the gesture of hello, but Linda withdrew, just as swiftly, into the shadows of her bedroom.

I didn’t mean to startle you, said Sonja.

Since she moved to this apartment, she had a garden right outside for the first time. She had to go down the stairs and around to the gate to access it, but even the visual closeness fostered in Sonja a new love of nature. When she moved in, the garden was concealed in a thick layer of snow, but she had seen it come alive this spring. At the living-room window, she set up a desk and let windborne seeds and insects disturb her at will. She was illustrating a volume on endangered birds, her first book project. If she had lived somewhere else, she might have stayed in advertising for-ever. The leap into freelance illustration, which she would take today, was spurred by how she felt when she opened these curtains every morning. She hadn’t joined the garden committee, but she enjoyed what they cultivated, and it was the birds she delighted in the most – her skylarks and goldfinches. She learned that you could make as much noise as you wanted, but sudden movements would startle them and cause them to fly away. Sonja learned to keep completely still while she observed birds, and so she was disappointed with herself now when Linda noticed her and took flight. Sonja was not some stranger. This was a contact-seeking old woman, so it was hurtful to see her pull back and slam the window shut without even saluting.

Sonja went back to fondling the window frames in search of the air current. These were the original windows and were composed of a crude form of double glazing, made by screwing an extra window frame to the first, on the inside. There was certainly no insulating vacuum between the layers of glass, because flies and ladybirds had found their way in there, years or perhaps even decades before, and their bleached bodies remained, a testament to some passage the air might also take. Sonja found no draught, for all her searching, but she took some towels and socks from the washing basket and packed them along the edges of the window all the same. Dispensing with the tug of frugality, she turned on the radiator full blast and went back to bed.

Somewhere above her, a child was crying, probably little Teddy on the top floor. In a weak and desperate moment, Sonja had considered asking them if they needed a babysitter. Things were tight now, but it wouldn’t last forever, and she owned this apartment, which was the main thing. It had been worth staying with the office until her loan was approved and she got set up here, but she longed for this freedom. Today was her last day in advertising – ever, maybe. Tomorrow she would be a full-time freelance illustrator.

The draught was still there.

She got up and rooted in the bottom drawer where she kept the bulk of her odds and ends. She found nail scissors and a roll of gaffer tape.

She sealed the window meticulously, but, when she moved away, the airstream was strong as ever.

Why now? She needed eight hours of undisturbed sleep before her final day. She wanted to walk out of that stifling office beaming and fluttering free.

She ran her hand over the wall, a centimetre from the surface, and – there it was: cold air pushing against her palm. This wind was blowing through the wall itself.

She rubbed her palms briskly against her thighs and tried again. It was the same: air, coming right through the wall. She placed a cheek close by the surface and real wind blew over her skin.

She looked out the window to the top floor of the opposite building, where the architect couple lived: Frida and Fritjof, she could ask them. They seemed approachable. They had been keen to chat at the garden clean-up that spring, though perhaps keener on chatting than working.

She noticed that all the windows on that block were open, every single one. It was a Norwegian thing. They were mad about fresh air. She had grown up in Ireland, where a window opened for any length of time inevitably brought in flies or spiders.

Her room was being aired, whether she liked it or not. She had used paint that let the wall breathe, the safest, most environmentally friendly variety on stock, the one with low vapour emissions, but breathable paint was meant to allow residual moisture to escape from the wall. It was not meant to facilitate this level of deep yogic breathing.

She checked the other walls in her bedroom, the internal walls and the party wall, and they were all fine. This one was the problem: the exterior wall that separated Sonja’s bedroom from the back garden. She went out to the living room where this wall continued, and there she found the same cool rush of air.

It was not the same all over. It seemed to be seeping through specific patches. Perhaps these were the positions of old vents that had been sealed up badly, though she could make no sense of the spread. As far as she could make out, standing on a chair and checking the whole surface, there seemed to be seven, possibly eight patches that were leaking air. There could hardly have been so many vents.

She looked at the brickwork and plasterwork on the opposite building and particularly at Linda’s apartment, directly opposite hers, her mirror image. There was only one vent on Linda’s façade, and that was under the living-room window. Sonja had one in the same position, with a little lever to open or close the damper inside. It let air in behind the radiator. It seemed to be working fine, despite the chirping she heard there a month ago, when a family of sparrows moved in for a week. Sonja mentioned this to Eva Holt, the proud head of the board of residents, so they could put in a net before next year or check if the birds were actually doing any harm. The birds didn’t bother her. She found their twittering heart-warming. But the noise was gone the next day, and she was too scared to ask Eva if she had made the caretaker get rid of them. Eva was an action-oriented leader. She should really ask her about the wall. External walls were the common responsibility of the board.

Sonja had a sudden sense of urgency, some mounting fear she couldn’t name until she realized that she could hear an ambulance. It was not far away and coming closer. Maybe all worry was a Doppler effect.

Knut

A key scratched and clicked in the lock, and Knut looked up from the floor. He had the drawers out and emptied, and all the shoes lined up. Une held the door open for Bibbi, who was carrying Teddy in her arms. His face was full of chocolate.

You look like you licked a bear’s bum, said Knut.

God, I’m starving, said Une.

Did they get them all out?

No, said Bibbi, he hadn’t swallowed any. They did an ultrasound and an X-ray. Did you find them all?

Knut looked around him.

It’s either old age that’s catching up with me, he said, or …

Did you put them up high this time? said Une, taking off the jacket with the missing buttons.

I didn’t find any marbles, said Knut, not one. I’ve checked everywhere.

He looked at the line of shoes, the rolled-up doormat.

Une and Bibbi cracked into laughter simultaneously. It was the kind of cheer that came out as strong as tears, maybe because it felt deserved.

He’s lost his marbles, said Une.

This was the first time Bibbi had laughed properly since she came back to them, so the whole ordeal was worth it, in a way. Even Teddy joined in, but when they stopped Bibbi said, Well they’re here somewhere. We’ll have to keep our eyes on him.

As Knut rose from the floor, he thought he was having a dizzy spell, because blue lights reflected in flashes on the ceiling. He went to the window in Bibbi’s room and looked down onto the street.

Why did you call an ambulance? said Une.

She opened the door to the stairwell, and they all waited as footsteps came up the stairs. From the floor below, there were three thuds and the sound of splintering wood.

Hildegunn, said Knut, going down to the half-landing. He could hear her screaming and moaning quite clearly. He went past Hildegunn’s broken door and down to the entrance, where a paramedic was holding the front door open with his back.

Keep the passage clear, he said, pointing to where Knut could stand. Do you know the woman on the third floor to the left?

That’s Hildegunn Lofthus-Lund, said Knut. We live right upstairs from her.

Any family we can contact?

They’re all abroad, said Knut. Her husband passed away. I’ll ask the head of the board of residents though. I think there’s a nephew in Oslo.

He broke off then as two paramedics manoeuvred a narrow stretcher down the stairs. Knut was in no doubt it was her hip that had gone, swelling her slacks on one side. Even though Hildegunn’s arms were fixed in place, the tendons on her wrist strained against the strap and she managed to point a wizened finger at Knut as she passed.

It was him, she said. It was those Klevelands with their marbles. They did this. They’ve been plaguing me for weeks. They did it. Vengeful tramps. Son of a tramp! she called out, her eyes latched onto Knut, even as they slid her into the back of the ambulance.

Hildegunn’s door was hanging open when Knut went upstairs, the wood splintered around the lock and the hinges distorted. He knew he shouldn’t, but he pushed it in.

It smelled distinctly of old woman in there, the same cobwebby smell that still had not left their apartment upstairs. Linda and Hildegunn had a long-term feud going, which Knut had never understood, but he had to admit that Hildegunn’s apartment was more stylish. Everything he saw, from the Arne Jacobsen lampshades to the Vitra coat stand, was fifties-style, light and industrial, and well designed. His own apartment seemed like a cluttered cabin in contrast.

He shuffled further into the apartment with the odd idea that this rare opportunity should not be missed.

A deep, rolling sound, followed by a click, caused him to look down at the polished wooden floor. Strewn about, and along the edges of the hallway, he saw dozens of glass marbles.

He gathered them quickly into his pockets, counting as he went. He tried to picture the game of solitaire, to know how many he should collect. He found twenty-eight.

In a wide wooden bowl on the hall table he found two others, along with some spherical buttons he recognized from Une’s knitted cardigan.

Is she all right? said Une, when he came back upstairs.

Broken hip, poor woman, he said.

Bibbi was changing Teddy’s nappy in the bathroom, an operation he was audibly resisting.

I’d better call Eva, said Une, to get in touch with her family. I told Eva we should have a digital file with all the information about the building and residents, but she’s holding those cards close to her chest.

They’ll have to fix her door. Come here.

Une followed him into the kitchen, where he emptied his pockets into the general waste bin.

They were strewn all over her hallway, he said. You went in?

Knut looked at her. He took the pot and wooden spoon, scraped the coagulated porridge on top of the marbles and buttons, and tied the bag closed.

Were those my buttons? I could have sewn them back on.

I’ll take this out, he said, and can you put that jacket in a plastic bag? I’ll bring it to the recycling.

My jacket? I can get new buttons.

You’re missing the point.

You don’t actually think she came up and stole our marbles?

No, but they were down there, on her floor.

She probably has her own game of solitaire.

No.

You found my buttons downstairs?

They both stared at the plastic bag of rubbish.

They were all over her hallway, said Knut. Will you give Eva a ring?

Maybe we shouldn’t.

Just ask about her nephew. Say she broke her hip, that’s all.

Did they really break her door in?

It was well they did, said Knut. She was out of her mind with pain. Tell Eva that. Tell her Hildegunn was saying crazy things.

Eva

What was that smell?

Eva was still wet from the shower when her mobile rang, but she answered immediately. She presumed it was someone from the office, an emergency only she could address: some information she alone was privy to, some encouragement needed before a meeting with a tough client that Eva would know how to handle. Her helpline, she affectionately called it. She clocked up all the time she spent on the phone when out of office. It was hours some days. She didn’t mind helping. She just needed her efforts to be acknowledged, in monetary terms.

Hello, she said, Eva Holt.

The strangest thing happened – I mean the most terrible. Poor Hildegunn seems to have broken her hip.

It was Une Kleveland, and there was something suspicious about the way she spoke. Eva had asked her to email, but ever since Une joined the board of residents last year, she rang all the time, usually prefacing whatever it was with, I’m not sure if this is something for us. She thought she had joined a club and wanted the full induction programme. Eva appreciated that the other board members deferred to her, but, instead of helping out, they seemed to increase her own workload.

That terrible smell though … She checked the loo.

Doesn’t she have a nephew in Oslo? said Une. I know her own children moved abroad.

If Hildegunn’s apartment came on the market, Eva was interested. She had been inside a number of times. Their two third-floor apartments were approximately the same size, but Hildegunn’s was at the end of the opposite block and so had windows on three sides. Eva’s was a one-sided apartment, facing onto the garden and the opposite block. She could never look away from her neighbours. Eva had grown up in a traditional detached house in the outer suburbs, and these modernist blocks had always given her the feeling that she was missing out on something, some avantgarde, freethinking ideal that had been denied her. She was in now, just not so completely as Hildegunn. Hildegunn’s apartment was a homely museum, a testament to the ambition and optimism of the fifties.

A nephew? said Eva. Let me just check here.

It was like falling in love with yourself, this feeling that came over her when she observed a desirable life. She wanted to be the one living it. Even the knowledge that Hildegunn was gone off to hospital with a broken hip did not deter her imaginings. To be young in the fifties, to live in a home made of light, floating elements, with thoughts and musings stacked behind each piece of furniture, which should be placed just so. Eva imagined that Hildegunn’s apartment could live all by itself, that even without occupants it would continue its ideal life: coffee brewing, flower boxes receiving a trickle of water from a stainless-steel watering can, a silver cat leaping onto a windowsill to stretch out in the sun.

Did you hear me? said Une. I said they broke the door into Hildegunn’s apartment.

I have a spare key! said Eva. There was no need to ruin the door.

We didn’t know what was happening. Hildegunn rang for the ambulance herself, so she must have told them to kick in the door. It was a medical emergency, you know. She was out of her mind with pain, talking absolute nonsense, poor woman.

Eva put Une at ease, told her not to worry, that she, Eva, would sort it out. She asked Une to look out for Hildegunn’s cat, in case it escaped.

When Eva hung up, the awful smell seemed to jump at her again, as if it had retreated to the background, out of politeness, while she was occupied on the phone.

Before she put down the phone, it buzzed again, with a message from Sonja Flynn. Despite the fact that her contributions were in arrears, she was asking for an insurance assessment. If it wasn’t something as serious as an exterior wall, Eva might have told her to pay up first.

The smell was horrible. It was shit; that’s what it was. There was no denying it, but it wasn’t coming from the toilet. The windows were all open, though Eva could not remember opening them. She must have done it during the night and forgotten. It had been so warm, so clammy.

If they were digging up pipes she should have been informed, as head of the board of residents. She unlocked the door to the balcony, to check if there was a leakage from the sewage system down on the street.

The five-metre-long flower box was full of earth to weigh it down and prevent it from blowing off, but it contained no plants yet. It was she who had ordered these copper flower boxes, reproductions of the originals which had been replaced by boxes made from asbestos in the seventies. She would get Ellie, her cleaner, to plant heather at some stage. Heather mostly took care of itself, she had read. She allowed herself this practical consideration for a prolonged moment, and then her attention was drawn downwards to the middle of the balcony floor slab. A wretched coil of excrement – dog poo, in fact – lay there, reeking and taunting.

She leaned over the edge of the balcony and looked up and down at the apartments above and below. It was impossible. She was on the third floor and there was no way for any dog to climb up here. At the other end of this block there were ivy creepers, which some superhero dog might plausibly have climbed, but here, by her apartment, the walls were of fair-faced brick. This was not a façade that anyone, human or canine, could climb. She had only one theory, and it was so extreme it baffled her. Magic seemed almost more likely, but it was the only possibility: on the floor above, in the best apartment in the block, with 150 square metres of internal area, a large roof terrace and a balcony, there lived a couple of architects who had a dog.

There was always something strange about Frida and Fritjof, like they were not entirely present in the conversation. They were beautiful people, maybe that was it, and, critically, they had a beautiful dog, a Rhodesian ridgeback. It was the colour of the shit on her balcony. Even this thought could not make Eva dislike the dog. It was sleek and svelte, and, if she ever decided to get a dog, it would be a breed she would consider, solely for its looks – and its demure nature.

That dog was huge. It must weigh as much as herself. Frida and Fritjof were tall, so the dog seemed the right size for them, but – there was no way that huge animal could have climbed down. If the faeces did belong to the beautiful dog, it was its owners who, out of some deeply concealed contempt, had managed to lower the stinking pile down here.

She craned her neck to see up to the nearest window above her and the balcony right over her own. Could they really have done it? The physical feat and the audacity were equally perplexing. If the poo had lain along the edge of her balcony, on the bare flower boxes, it would at least make physical sense. They might have somehow brushed it off. But this was not something that had splattered down. It was a perfectly formed piece of excrement, coiled in a direct depiction of the colon it came out of. It was provoking. It was absolutely enraging. Really, she should just clean it up, but she was so astounded she could hardly move. Could it be some bird, she wondered, who left droppings like a dog? She had once seen a crow eating a cowpat, a most revolting sight. It ruined crows for her, despite their purported intelligence. She considered whether a crow could have eaten some dog’s excrement down on the street, then flown up here and thrown it up.

No. This was dropped right here from a crouching hound. It was the only thing that made sense, and it made no sense at all.

Raj

It was almost 10 pm as Raj neared home, his research in digital technology and leadership still tinkling connections and potentials in his head. The forty-minute walk from the university was like descending a mountain of knowledge. The fact that he concluded the descent in a basement flat contributed to this impression. His was a cerebrally intensive existence. The research institute he worked at was beside the university so, when the workday ended, he could go, via dinner in the student canteen, to the lab or the library to work on his postdoc: convenient, but physically slothful. He needed these two daily walks. His body was the benevolent host to his brain, a rich aunt who would support you if you toed the line. Sidewards glances from women he passed on campus suggested he was not doing so bad a job on corporal maintenance. If these women came too close, though, they might smell his apartment off him.

For the last week, after noticing that some of his colleagues talked to him from a greater distance, or just waved where they would previously have come over and fist-bumped, Raj had started taking his showers in the changing room at work.

A fortnight earlier, his flatmates, Krishna and Pradeep, had found a notice in their letter box about the smell, telling them to use the ventilator when they showered, to consider their neighbours when preparing food, to use, or indeed install, an extractor fan over the cooker, to keep the door to the stairwell closed at all times, especially when food was being cooked. When they received this recipe for civilized living early one morning – that is to say, it had been placed in their letter box late at night – Raj noticed that neither the part-time dad on their storey nor any of the others had a similar note folded and sticking out of their letter box. None of his neighbours were suspects.

Not only were Raj and his flatmates extracontinental foreigners – who, it seemed, needed to be told the basic rules that allowed Europeans to live side by side – not only this, but they were also tenants. Eva Holt, head of the board of residents, had not-so-casually bumped into Pradeep soon after they moved in and told him that they were the only tenants. All the other apartments were owner-occupied, so she just wanted to say that they had only to ask if there was anything they were unsure of, and had their landlord given them the house rules? If not, she happened to have a copy on her.

All the other residents came down to his storey from time to time to get to their storage rooms, and they inevitably complained about the smell. It was probably one of them who had stashed away something horrendous, a slaughtered elk in a malfunctioning freezer, though it was not the smell of rotting flesh. There was certainly nothing Indian about the smell, a fact that should have exonerated Raj and his flatmates. There was nothing particularly foreign about it even, whatever that meant. It was not a spicy, aromatic or pungent smell. It smelled of basement to a factor of ten. It smelled wet, or damp, even though the surfaces were dry. He had looked up dry rot and fungal growths and checked along the floor and behind the furniture. There were no characteristic black spots; there was no rotting wood. It looked fine – but it smelled intense.

It hadn’t always stunk. When they moved in it had been all right – a fact that made the whole situation worse, since there was a temporal link between their tenancy and the smell. Worried about their deposit, they had been eating salads and taking cold showers to avoid steam for the past fortnight, but the smell only got worse.

They paid a three-month deposit when they signed the tenancy contract, all three of them, but they had only lived there for one month. The other two were as tightly strung on student loans as Raj was, otherwise they would have looked for a place somewhere else. Next time he would rent somewhere on a higher storey. He could probably get something cheaper closer to the university, and he could get his exercise by jogging. He didn’t benefit from the central location of his apartment. It was just expensive.

There must be something they could do about the smell. He was the only son of scientists and maybe that was why he could not let it rest, why he needed to understand.

Raj, Pradeep and Krishna all worked in IT, worked by day and researched in the evenings, or the other way round in Krishna’s case, since he was still contracted to a Delhi-based company. Dealing with smells was not within their skill sets. Scent and taste were still way off on the edges of virtual reality, the last unconquered senses.

As he walked down the street he saw Krishna inside, attempting to open his bedroom window to a greater angle. They shrugged at each other. There were bushes directly outside the windows, so Raj always felt he was peeping out of a hiding place when he looked out. They mainly kept their curtains drawn, however, as people – strangers as well as neighbours – tended to gape in as they went by. It could be that some people thought single flatmates were in a public sphere with each other, not being related, so it was less of an intrusion to stare in at them, less provocative to suggest they stank. Perhaps these people believed that families lived in homes, whereas young single males, especially academic migrants, never lived in more than a flat or apartment. Raj did not think of that stinking hole as his home. It was just a place to stay and, increasingly, a place he was glad to leave every morning.

It was called a basement apartment, but the floor inside was only a couple feet under the level of the narrow garden along the street. Because of how the streets sloped, whoever designed these buildings had managed to shoehorn Raj’s apartment and one other in under the rest of the apartments, in front of the basement storage rooms. For all he knew, the apartment they rented might once have been part of the cellar, and he and his flatmates were in temporary storage.

The part-time dad’s red-nosed face leered at him through his basement window, and Raj wondered if this meant he too was one of those who dared look in at ground-floor residents, if he was entitled to do so since others did the same to him, or if it was the movement of the man, right behind the glass, which had caught his attention. Raj averted his gaze as neutrally as he could.

As he came through the glass doors, a silver cat darted slipper-silent up the stairs. Even cats could not abide the smell – or this cat might be in the habit of urinating down there. This beautiful feline might not be so beyond reproach and thoroughly refined as one would expect from her graceful movements and the dazzling gloss of her fur.

His red-nosed neighbour was peering from his door as Raj came down the half flight of stairs to his apartment. A whiff of whiskey tinctured the overwhelmingly subterranean odour.

Was that your cat? said Raj.

I want you to know, said the man, that I have a little daughter, a seven-year-old girl, a pure princess, who I bring to my home from time to time, for the weekend. Do you know what it is like to have your own daughter say your home stinks? I tell you, young man, I am meticulously clean. It is simply not fair, what you’re doing: you and your chums stinking out the whole floor. You know the rules; you’ve been given notice. Now, just show some respect, can’t you?

His monologue complete, the man slammed the door.

Not your cat then, said Raj.

As he came inside, a noise drew his glance inwards along the floor. Mice, four at least, shuttled in various directions and disappeared, hidden who knows where.

He checked under his own bed. That would be the worst. He closed his bedroom door, but opened it again, because he didn’t want to block them in.

He heard a low meowing out in the stairwell. In his hurried mouse chase, he had left the door unlocked.

Pss-pss-pss, he said. Here, pussy pussy.

He held the door open and stood well back so as not to frighten the animal. She kept her eyes on him as she passed and then made straight for the kitchen.

Pradeep came out of his room, and Raj put a finger to his lips.

We have mice, he said.

Krishna came out too.

Is that your cat? he said. It is not allowed.

We have mice, said Pradeep, putting on his jacket. I’m going out to get a trap.

We’ll need a few, said Raj, but the hardware stores will all be closed now.

I’ll try the shopping centres.

I’ll come with you, said Krishna. There are humane traps we could get.

Stay with me, said Raj. We should tidy up and seal all the food. Get some tape too, Pradeep, will you?

Text me if there’s anything else, said Pradeep, already out the door and tapping up the half-flight of stairs at speed.

Raj heard squealing and hissing from the kitchen.

Where did you get the cat? said Krishna.

It just came in.

He held the door ajar and allowed the cat to go out with a small mouse in her mouth – alive or dead, he couldn’t tell – and to come back to fetch another and another.

They waited quietly as this happened. Raj stood aside in the hallway, so he would hear anyone coming on the stairs. He didn’t show himself at the door, in case the alco-dad could see him through his spyhole. If anyone came and saw the door ajar, they would be accused anew of spreading their dinner odours into the stairwell. This despite the fact that none of them had cooked dinner and none of them would have the appetite to eat anything now.