Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

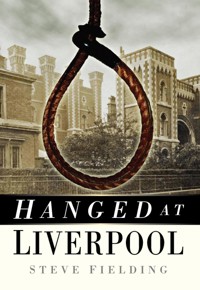

Over the years the high walls of Liverpool's Walton Gaol have contained some of the most infamous criminals from the north of England. Taking over from the fearsome Kirkdale House of Correction as the main centre of execution for Liverpool and other parts of Lancashire and neighbouring counties, a total of sixty-two murderers paid the ultimate penalty here. The history of execution at Walton began with the hanging of an Oldham nurse in 1887, and over the next seventy years many infamous criminals took the short walk to the gallows here. They include Blackburn child killer Peter Griffiths, whose guilt was secured following a massive fingerprint operation; Liverpool's Sack Murderer George Ball; George Kelly, since cleared of the Cameo Cinema murders, as well as scores of forgotten criminals: soldiers, gangsters, cut-throat killers and many more. Steve Fielding has fully researched all these cases, and they are collected here in one volume for the first time. Infamous executioners also played a part in the gaol's history. James Berry of Bradford was the first to officiate here, followed in due course by the Billington family of Bolton, Rochdale barber John Ellis and three members of the well-known Pierrepoint family, whose names appeared on the official Home Office list for over half a century. In 1964 one of the last two executions in the county took place at Liverpool. Fully illustrated with photographs, new cuttings and engravings, Hanged at Liverpool is bound to appeal to anyone interested in the darker side of both Liverpool and the north of England's history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 264

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2008

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

HANGEDAT LIVERPOOL

STEVE FIELDING

First published 2008

The History Press The Mill, Brimscombe Port Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

Reprinted 2010

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved © Steve Fielding, 2008, 2013

The right of Steve Fielding to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 5337 5

Original typesetting by The History Press

CONTENTS

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Research Materials & Sources

Introduction

1. ‘The Worst Species of Womankind’

Elizabeth Berry, 14 March 1887

2. ‘For a Good Cause’

Patrick Gibbons, 17 August 1892

3. A Positive Identification

Cross Duckworth, 3 January 1893

4. The Prisoner in the Attic

Margaret Walber, 2 April 1894

5. ‘For Her Unfaithfulness’

John Langford 22 May 1894

6. The Man with the Twitch

William Miller, 4 June 1895

7. The Railway Thieves

Elijah Winstanley, 17 December 1895

8. Mitigating Circumstances?

Thomas Lloyd, 18 August 1897

9. ‘No Other Man Shall Have Her’

James Joseph Bergin, 27 December 1900

10. Horror at Rose Cottage

John Harrison, 24 December 1901

11. The Estranged Husband

Thomas Marsland, 20 May 1902

12. The Veronica Mutineers

Gustav Rau & Willem Schmidt, 2 June 1903

13. The Maintenance Order

Henry Bertram Starr, 29 December 1903

14. The Sister-in-Law

William Kirwan, 31 May 1904

15. The Gambling Den Murder

Pong Lun, 31 May 1904

16. The Lodger

Charles Patterson, 7 August 1907

17. Rivals

See Lee, 30 March 1909

18. At The Second Attempt

Henry Thompson, 22 November 1910

19. The Old Sailor

Thomas Seymour, 9 May 1911

20. The Child-killer

Michael Fagan, 6 December 1911

21. The Drunken Husband

Joseph Fletcher, 15 December 1911

22. The Liverpool Sack Murder

George Ball, 26 February 1914

23. ‘That Terrible Thing’

Joseph Spooner, 14 May 1914

24. A Bucket of Dirty Water

Young Hill, 1 December 1915

25. The Stalker

John James Thornley, 1 December 1915

26. Entanglement

William Thomas Hodgson, 16 August 1917

27. The Man Who Came Back From the Dead

John Crossland, 22 July 1919

28. Suicide Pact

Herbert Edward Rawson Salisbury, 11 May 1920

29. The Valentine’s Day Murder

William Waddington, 11 May 1920

30. A Fatal Slip-Up

James Ellor, 11 August 1920

31. The Business Card

Frederick George Wood, 10 April 1923

32. Torn Between Two Lovers

James Winstanley, 5 August 1925

33. ‘What The Law Orders’

Lock Ah Tam, 23 March 1926

34. ‘My Best Girl’

James Leah, 16 November 1926

35. No Luck Anywhere

William Meynell Robertson, 6 December 1927

36. ‘Playing This Game For Too Long’

Albert George Absalom, 25 July 1928

37. Hypnotic Charms

Joseph Reginald Victor Clarke, 12 March 1929

38. ‘Poor Johnny’

John Maguire, 26 November 1929

39. ‘A Tissue of Lies’

Richard Hetherington, 20 June 1933

40. A Sailor’s Revenge

Jan Mohamed, 8 June 1938

41. The Wounded Thumb

Samuel Morgan, 9 April 1941

42. On a Weekend Pass

David Roger Williams, 25 March 1942

43. The Ladies’ Man

Douglas Edmondson, 24 June 1942

44. To Solve His Financial Problems

Ronald Roberts, 10 February 1943

45. The Woman in the Cellar

Thomas James, 29 December 1943

46. A Life for a Life

John Gordon Davidson, 12 July 1944

47. In the Basement Brothel

Thomas Hendren, 17 July 1946

48. Five-Day Love Affair

Walter Clayton, 7 August 1946

49. ‘My Lost Love’

Arthur Rushton, 19 November 1946

50. Beneath the Floorboards

Stanley Sheminant, 3 January 1947

51. ‘Operation Fingerprint’

Peter Griffiths, 19 November 1948

52. Chance Medley

George Semini, 27 January 1949

53. The Cameo Cinema Murders

George Kelly, 28 March 1950

54. The Alibi

Alfred Burns & Edward Francis Devlin, 25 April 1952

55. The Old Curiosity Shop Murder

John Lawrence Todd, 19 May 1953

56. Under a ‘Defect of Reason’

Milton Taylor, 22 June 1954

57. The Body in the Canal

William Arthur Salt, 29 March 1955

58. ‘Until the Other One Came’

Richard Gowler, 21 June 1955

59. The Wigan Child Murders

Norman William Green, 27 July 1955

60. The Last to Hang

Peter Anthony Allen, 13 August 1964

Appendix I. Public Executions outside Kirkdale House of Correction 1835–1865

Appendix II. Private Executions at Kirkdale House of Correction 1868–1891

Appendix III. Private Executions at Walton Gaol 1887–1964

Memo on how to carry out an execution. (Author’s collection)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Steve Fielding was born in Bolton, Lancashire in the 1960s. He attended Bolton County Grammar School and served an apprenticeship as an engineer before embarking on a career as a professional musician. After many years recording and touring, both in Great Britain and Europe, he began writing in 1993 and had his first book published a year later. He is the author of over a dozen books on the subject of true crime, and in particular hangmen and executions.

Hanged at Liverpool is the third in a series and follows Hanged at Durham and Hanged at Pentonville (both Sutton Publishing). He compiled the first complete study of modern-day executions, The Hangman’s Record 1868–1964, and, as well as writing a number of regional murder casebooks, is also the author of two titles on executioners: Pierrepoint: A Family of Executioners and The Executioner’s Bible – Hangmen of the 20th Century. He is a regular contributor to magazines including the Criminologist, Master Detective and True Crime, and is Historical Consultant for the Discovery Channel series The Executioners, and Executioner: Pierrepoint for the Crime & Investigation channel. Beside writing, he teaches maths and English at a local college.

Forthcoming titles in the series include:

Hanged at Manchester

Hanged at Leeds

Hanged at Birmingham

Hanged at Wandsworths

Hanged at Durham

Hanged at Pentonville

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank the following people for help with this book. Firstly to Lisa Moore for her help in every stage of the production, but mainly with the photographs and proofreading. I offer my sincere thanks to both Tim Leech, who once again allowed me access to his archives, and to Matthew Spicer, who likewise was willing to share information along with rare documents, photos and illustrations from his own collection. I would also like to thank Janet Buckingham for her help in inputting much of the original data and to Gillian Papaioannou who proofread and edited early drafts of the text. Thanks also to Stewart McLaughlin who helped with information and papers relating to HMP Liverpool.

RESEARCH MATERIALS & SOURCES

As with my other books in this series and with the subject of capital punishment and executions in general, a great number of people have helped with information, anecdotes and photographs. I remain indebted to the help with rare photographs and material given to me by the late Syd Dernley (assistant executioner) and former prison officer, the late Frank McKue.

Research on cases, which would eventually form this book, began many years ago, with extra information added to my records as and when it has become available. In most instances, contemporary local and national newspapers have supplied the basic information, which has been supplemented by material found in PCOM, HO and ASSI files held at the National Record Office at Kew. I also had access to the Home Office Capital Case File 1901-1948, along with personal information, papers, diaries, photographs etc. from a number of those directly involved in some of the cases.

Space doesn’t permit a full bibliography of books and websites accessed while researching this project. I have tried to locate the copyright owners of all images used in this book, but a number of them were untraceable, in particular those sourced from the National Archives. I apologise if I have inadvertently infringed any existing copyright.

INTRODUCTION

Work began on a new gaol in Liverpool early in 1850. Situated on Hornby Road, Walton, and covering nearly 20 acres, it took almost five years to complete, at a cost of almost £3,500, and a company named Furness & Co was tasked with carrying out work. Architects Charles Pierce and John Weightman based the plans on the radial or panopticon design that had proved a big success in several newly-built American penitentiaries and more recently at London’s Pentonville Prison. This new design allowed a warder a panoramic view of all the prison wings from a central area, and prisoners now had there own ‘separate’ cells with improved lighting and sanitation facilities.

At the time of completion, Walton was the most modern prison in the country and had been commissioned to replace the archaic New Borough Gaol. Situated close to the dockside, the old gaol had, at one time, been a holding pen for slaves bound for the West Indies and the Americas and had also held so many French prisoners of war during the Napoleonic Wars, it became known locally as the French Gaol.

Liverpool became an Assize town in 1835. Prior to this, criminals tried for crimes in the city were taken to either Chester or Lancaster for trial and execution. The first execution in Liverpool took place in August 1835, in public, outside the walls of Kirkdale House of Correction. Despite the construction of the more modern Walton Gaol, Kirkdale was still the main prison serving Liverpool, and in the latter years of the nineteenth century, it gradually became the main centre of execution for the county of Lancashire. All executions took place outside the prison walls and in some instances, crowds of up to 50,000 would congregate to witness the gruesome spectacle. (See Appendix I for a complete list of public executions at Kirkdale.)

The imposing courtrooms at St George’s Hall were opened in the 1854, and it was here, throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, that numerous infamous trials were held, many that filled the pages of the newspapers across the whole country. It was also here, where the majority of those hanged at Liverpool were sentenced to death.

Walton Gaol had originally been conceived to hold one thousand inmates and took both male and female prisoners. With executions of male prisoners still carried out at Kirkdale, following the Private Executions Act of 1868, it was decided that females sentenced to death would henceforth be hanged at Walton. Elizabeth Berry was the first to go to the gallows here (seechapter 1) and Mrs Berry’s terror as she heard the prison carpenters erecting the scaffold was also shared by the next inmate in the new condemned cell at the gaol.

In 1889, American born Florence Maybrick, convicted of the murder of her husband by poisoning him with arsenic, came within days of being included in the list of those hanged at Liverpool, before the intervention of the American authorities persuaded Queen Victoria to sanction a pardon. The Maybrick case returned to the headlines in the 1990s when a diary and papers found beneath the floorboards in a renovated house in Liverpool seemed to suggest that James Maybrick, the victim in the case, had in fact been the notorious London murderer Jack the Ripper. Maybrick’s untimely death had coincided with a halt to the reign of terror. Whether this is true or the diaries are a forgery is still the subject of debate.

In 1890, inmates from Kirkdale were transferred to Walton, being marched under armed escort from prison to prison, and although all prisoners were now sent to Walton to serve their sentences, executions continued at Kirkdale until August of the following year. Kirkdale closed completely in 1892 and was later demolished; a park now stands on the spot where the gaol once was. (A list of latter day executions at Kirkdale can be found in Appendix II.)

The first gallows constructed at Walton was situated in the coach house in the grounds of the prison. Following the passing of sentence of death on Mrs Berry, a dozen inmates were hurriedly detailed to dig a large pit, which was then bricked up and the trapdoor and beam assembly constructed on top. It was seemingly believed that the prisoner would not be hanged, or at least not hanged at Walton, and as a result no effort had been made to construct a scaffold until she was brought to the prison pending execution.

By the turn of the twentieth century, Liverpool was one of busiest centres of execution in the country, dealing with condemned prisoners from all parts of the north-west. In the years leading up to the First World War, there were several nearby prisons that housed a gallows: both Knutsford and Lancaster played host to the hangmen, as, of course, did Manchester’s Strangeways Prison. When Knutsford was closed down and Lancaster downgraded during the First World War, all subsequent convicted criminals went either to Liverpool or Manchester for execution. Likewise, when Stafford Gaol was similarly requisitioned as a military prison and detention centre in 1916, a number of condemned criminals from Staffordshire also found themselves in the condemned cell at Walton.

In line with Home Office recommendations, work began early in 1929 on modernising the execution suite, which was to now be situated on landing two, I wing, where it remained in regular use until abolition.

Like other gaols around the country, Walton did not retain its own executioner. The undersheriffs of the county in which the condemned prisoner had been sentenced retained a copy of the short Home Office list of hangmen and assistants and selected an executioner from that, with the prison governor being responsible for recruiting the assistant executioner. Initially the hangman had worked alone but by the turn of the century it became common, and then eventually a rule, to employ an assistant executioner.

The first hangman to officiate at Walton was former Bradford policeman, James Berry. Berry had been an executioner since 1884 and had been a frequent visitor to the city, officiating at Kirkdale on a number of occasions, and where he came into contact with Medical Officer Dr James Barr. The relationship between these two men was to become strained in August 1891 when they failed to agree on the correct drop for a man to be hanged for a brutal child murder. Berry wanted to give the prisoner a drop of under 5ft; Dr Barr insisted nearer 7ft was suitable. When the prisoner dropped to his death on the following morning, there was a horrendous squelch from the pit instead of a thud and the prisoner was almost decapitated, with blood squirting everywhere. On the following day Berry tendered his resignation and blamed the doctor’s interference in this execution as his reason for doing so.

James Billington succeeded Berry, and even though Billington had been carrying out executions on his own since 1884, he was still sent to Kirkdale to receive further instruction in carrying out executions from Dr Barr. Barr had given evidence at the Aberdare Report in 1886, which had been set up following a number of botched executions by James Berry. Following the retirement of Berry, the prison authorities began to take steps to make sure any future hangmen engaged or recruited to the list were suitable, both mentally and physically.

Billington carried out eight executions at Walton, often assisted in the later engagements by one of his sons. At the execution of Winstanley in December 1895, Billington was to have been assisted by Thomas Scott, a Huddersfield-born rope maker, who had acted as his assistant on a number of occasions across the country, and who had even carried out a number of jobs himself as a chief executioner. On arriving at Lime Street in good time, Scott decided to while away the afternoon in the company of a lady of dubious virtue. Scott and his companion, Winifred Webb, spent several hours together and their parting was the subject of a quarrel over a small matter of money.

Hangman James Berry, the first executioner to officiate at Walton Gaol. (Author’s collection)

Scott discovered he had been robbed of a pair of spectacles along with £2 9s 6d and contacted the police, only for the woman to counter this by saying he had given her the money as payment for her company. By the time the matter was resolved, Scott was too late to attend the prison and was unable to assist at the execution, leaving Billington to go to work alone.

Following James Billington’s death in December 1901, his son William officiated at the execution of John Harrison. The engagement had already been in his father’s diary, but responsibility was passed to William who carried out the execution assisted by his elder brother, Thomas. When William was next engaged at Walton five months later, Thomas had also passed away and William’s assistant on this occasion was his younger brother, John.

Henry Pierrepoint assisted William Billington on two executions at the gaol and during his reign as a chief executioner, he also officiated twice at Liverpool. His assistant on both occasions was his elder brother, Thomas. Thomas Pierrepoint also worked as an assistant to John Ellis in 1911 but it would be over fifteen years before he was next on duty at Walton Gaol.

John Ellis carried out twelve executions in thirteen years, including two doubles. Following his retirement in 1924, William Willis, who was living in Manchester, succeeded Ellis, but Willis was to officiate just twice at Liverpool before being struck off the Home Office list of hangmen. This short list was periodically updated, and it was the failure to use an up-to-date list that caused an unfortunate situation in 1926 when William Willis was engaged to execute James Leah.

Unbeknown to the hangman, he had been struck off the list following indiscretions at a previous execution at Pentonville a few months earlier, and when Willis received the letter he wrote accepting the engagement, only to receive a further letter withdrawing the offer of the job and telling the shocked hangman that he had been sacked. The engagement was then offered to, and accepted by Thomas Pierrepoint. Willis wrote several times to the Home Office asking for an explanation and begging for his job back but it was not to be.

Almost twelve months later when William Robertson was sentenced to death, Willis was contacted asking if he was free to officiate. Believing he must have served some suspension which had now been lifted, Willis wrote at once stating that he was available, but as before, he received a further letter several days later saying the offer had to be withdrawn, as he was no longer on the official list of executioners. The Home Office later wrote to the under-sheriff, haughtily reminding him that it was his responsibility to use an up-to-date list of hangmen when engaging an executioner and not one that was out of date.

Thomas Pierrepoint was the longest serving hangman at the gaol, executing thirteen men in a career that lasted almost forty years. Following adverse reports into his conduct during the early years of the Second World War, Tom Pierrepoint was subjected to a Home Office investigation, and an official report regarding the execution of Roberts at Walton in 1943 recorded that the aged hangman (he was 73 at the time and walking with a stick) deemed speed to be the basic requisite of an executioner’s capabilities. The memo noted that Pierrepoint was so swift in darting to the lever once the noose was in place, that assistant Harry Kirk barely had time to get clear of the trapdoors.

By this time Tom’s nephew and Henry Pierrepoint’s son, Albert Pierrepoint, was also an established executioner. Ten years earlier, in 1933, Albert had assisted his uncle at the execution of Richard Hetherington. It was Albert’s first bona-fide engagement as an assistant in a British prison, and over twenty years later, Pierrepoint’s career ended with an execution at Walton when he resigned a few months after hanging Norman Green.

Curiously, Manchester-born hangman Steve Wade, a rival to Albert Pierrepoint as a chief executioner in the post-war years, carried out just two senior executions at Walton, and on both occasions, the prisoners had been convicted for crimes that took place in Staffordshire.

Liverpool holds a place in the annals of criminal history as the scene of one of the last two executions to take place in Great Britain, when Robert Leslie ‘Jock’ Stewart hanged Peter Allen at the same moment that Allen’s partner-in-crime was hanged at Manchester.

Modern-day photograph of HMP Liverpool. (Author’s collection)

Walton had become an exclusively male prison in 1933. In 1941, parts of the prison were subject to damage from German bombs. Over twenty prisoners were killed in the raids, which demolished two of the eight wings of the gaol. In 1980 the prison was extended and extra cells were added, making its capacity of over 1,350 one of the largest in the country. Now covering an area of over 22 acres, it was officially renamed HMP Liverpool and continues to be in use as a prison to this day.

Here within its walls, over a period spanning seventy-seven years between 1887 and 1964, a total of sixty men and two women were to pay the ultimate penalty. This book looks in detail at the sixty cases in which the killers were all Hanged at Liverpool.

Steve Fielding, 2008

www.stevefielding.com

1

‘THE WORST SPECIES OF WOMANKIND’

Elizabeth Berry, 14 March 1887

On Saturday morning, New Year’s Day 1887, nurse Elizabeth Berry, a 31-year-old widow, was on duty at the Oldham Infirmary Workhouse. For the last three days her daughter, 11-year-old Edith Annie, had been staying with her at the hospital and that morning after Berry had prepared a pan of sago, her daughter ate a bowlful and became violently sick.

An hour later, with her daughter still vomiting, she asked one of the doctors to examine Edith and the child was prescribed a medicine, containing a mixture of iron and quinine. At lunchtime on the following day, the doctor examined Edith again and thought that she was over the worst, and would make a full recovery. Berry, however, told him that the girl was still being sick and showed him a towel stained with blood and vomit, which had a strange acid smell. The doctor asked for the key to the medicine cupboard so he could prepare a bicarbonate mixture. Mrs Berry had the only key to this cabinet and when the doctor opened it, he noticed a bottle of creosote on one of the shelves.

That night the child was again taken ill and this time the doctor noticed faint red blisters around her mouth. He consulted another doctor at the adjacent infirmary and the two decided that the girl must have taken a corrosive poison. She was given further medication, which she immediately vomited. The child began to weaken rapidly, and by the following day there was hardly any sign of a pulse and the doctors feared the worst.

Edith Berry died in the early hours of Thursday morning and because the cause of death was suspicious, an autopsy was ordered before a death certificate could be issued. With the help of a surgeon from Manchester Hospital, an autopsy was carried out which revealed the cause of death as by an acidic, caustic poison, similar in colour to creosote. Remembering the bottle he had seen in the medicine cabinet, the doctor informed the police and later that day, Mrs Berry was arrested for the murder of her daughter.

Her trial before Mr Justice Hawkins at Liverpool Assizes began on 21 February, and over the next four days, a number of medical experts all testified that the cause of death was corrosive poison.

The prosecution also suggested a motive claiming that in April 1886, Mrs Berry had received a sum of one £100 from an assurance society following the sudden death of her mother. It was found that later that year Mrs Berry tried to insure both herself and her daughter for £100 with the money to go to the survivor, after one or the other had died. Although she had not paid the full premiums, she had made a number of payments and would have expected the insurance to be settled. She was never to get a chance to make the claim.

The prosecution also suspected that she had poisoned her mother the previous year and five years before, had disposed of her husband in a similar fashion. In 1883, her son had also died suddenly and following this loss she had come to an arrangement with her sister-in-law for the upkeep of young Edith. Elizabeth was earning a yearly wage of £25, and she paid almost half of her salary to her sister-in-law for the child’s upkeep. With Edith’s sudden death, this payment ceased and helped support the prosecution’s claims that it was murder for greed and financial gain. The jury agreed and took just ten minutes to find her guilty as charged.

The execution date was fixed for Monday 14 March 1887 and Yorkshire hangman James Berry was engaged. On his arrival at the gaol, the governor met him with a smile. ‘I did not know you were going to hang an old flame, Mr Berry.’ he told the startled hangman. Berry insisted that he wasn’t and thought this was due to the confusion of their sharing the same surname.

‘Oh no, she tells me she knows you very well’ the governor said, ‘you had better go and have a look at her tonight. I will make the necessary arrangements.’

When Berry spied her in her cell, he recognised the woman as someone he had met in the past. They had been introduced at a policeman’s ball in Manchester, and after sharing refreshments and several dances, he discovered they were travelling home in the same direction, and invited her to join him in his cab. They parted with a friendly kiss when she alighted his train at Oldham railway station.

As there had not been an execution at Walton before, the prison did not have a designated condemned cell and Mrs Berry was housed in the female debtors’ wing, which was close to where the gallows was to be situated. She complained to the warders that she could hear the prison carpenters assembling the gallows in the adjacent coach house, and as a result, she was moved to a cell in another wing of the prison. With preparation for the scaffold completed, she was brought back to her original cell and it was here where Berry spoke to her on the night before her execution. When the hangman entered the cell she looked up and smiled.

‘Good evening Mrs Berry,’ he said kindly.

‘You’ve no doubt heard a lot of dreadful things about me, but it isn’t all true what people say,’ she told him, adding, ‘you need not be a bit afraid of me, Mr Berry. You don’t suppose I’d want to give you any trouble, do you?’

‘I hope you won’t give me any trouble,’ Berry replied, ‘I shall not prolong your life a single minute. Have you made your peace with God?’

As he left the cell, Berry was not convinced the prisoner would be true to her word and told one of the guards rather harshly: ‘That woman is one of the biggest cowards in the world.’

Snow was falling heavily on the morning of the execution, but despite this, the street outside the gaol was described in the local newspaper as being ‘black with people,’ eager to witness the black flag that signified an execution had been carried out, hoisted on the flagpole at Walton.

In company of the governor and prison doctor, Berry entered the cell at a minute before 8 a.m. ‘Is there anything I can do for you before you leave the condemned cell?’ Berry asked.

The prisoner shivered, slunk back into her chair and shook her head. With her arms pinioned, the governor led the way as the procession formed. The distance from the cell to the scaffold was around 60yd, and sand had been thrown liberally along the ground to prevent anyone slipping. Mrs Berry walked firmly until she turned the angle of the building and saw the gallows’ shed. At that, a cry of sheer terror left her lips.

‘Oh, dear!’ she wailed loudly, and slumped back as if in a faint. Berry rushed forward and steadied her. ‘Let me go, Mr. Berry,’ she begged, ‘let me go, and I will go bravely.’

Supported by two warders, she struggled to complete the final few yards until she reached the scaffold. ‘God forbid!’ she cried before collapsing into a faint. Warders held her beneath the beam as Berry completed his preparations and pulled the lever.

No sooner had the trapdoors crashed open, one of the wardresses approached the hangman. ‘There goes one of the coldest-blooded murderers. She must be the worst species of womankind to carry out the deeds she has carried out’ she spat bitterly.

2

‘FOR A GOOD CAUSE’

Patrick Gibbons, 17 August 1892

Following his discharge from the Lancashire Fusiliers in the summer of 1892, 33-year-old private Patrick Gibbons moved back to live with his parents on Water Street, Heyside, a small village on the outskirts of Oldham.

The homecoming was not a happy one and the family soon began to argue and fight almost daily. The root of the trouble was that both parents and son regularly drank to excess and this culminated in a drinking binge that was to end in tragedy.

By the morning of Saturday 9 July, Gibbons and his parents had spent the last three days in an almost permanent drunken stupor, and throughout that time, neighbours had heard constant raised voices, along with shouts and threats being made. Gibbons left the house before noon and went to a local pub where he consumed several drinks before returning home, and was seen by neighbours staggering along the street and clearly drunk.

His father was out at the time, leaving Patrick Gibbons’ 62-year-old mother Bridget alone in the house, sleeping off her hangover. Returning home, Gibbons picked up his razor, crept into his mother’s bedroom and as she slept he cut her throat. He then put the razor down and went to the house next door, asking a neighbour to come to their house.

‘Mrs Russell, go and look at my mother – I have done it,’ he told her. Asked what he had done, he replied that he had cut her throat. ‘Go and see for yourself’ he told her, before sitting down in a chair and waiting for her to come back. Mrs Russell entered the house, climbed the stairs and found Bridget Gibbons lying face down in a pool of blood. The body was still warm. The police were summoned and when Inspector Ormrod arrived and placed Gibbons under arrest, he said he had done it ‘for a good cause’ but did not elaborate.