Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

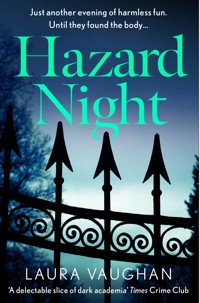

'A delectable slice of dark academia' Times Crime Club Cleeve College is not for everyone... When Eve's husband is appointed housemaster at his old boarding school, Cleeve College, she gives up her life in London to join him. But the isolation and loss of autonomy threaten both her happiness and her marriage. The arrival of Fen, an enigmatic artist and wife of the new Classics teacher, is a welcome distraction. Fen doesn't play by the rules, and she and Eve enter into a game of escalating dares, disrupting the delicate balance of school life. Then, the morning after Hazard Night, a tradition that allows the students to run wild and play pranks for one day, a body is found. Someone has been murdered. And it seems everyone has something to hide... 'Dark and devious, immersive, compelling ... wonderfully absorbing read' - Andrea Mara 'Atmospheric and sinister'- Observer

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 356

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Laura Vaughan grew up in rural Wales. She got her first book deal aged twenty-two and spent several years working in publishing, followed by a behind-the-scenes role at the English National Ballet. She lives in South London with her husband and two children. Hazard Night is her third novel for adults.

Also by Laura Vaughan

The Favour

Let’s Pretend

Published in trade paperback in Great Britain in 2023 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2024.

Copyright © Laura Vaughan, 2023

The moral right of Laura Vaughan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 710 0

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 709 4

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For my mother.

One day I’d like to be as good a reader as you.

EVE

The first Arrivals Day, Eve had felt exactly as she was supposed to. She hadn’t had to fake the warmth in her voice or the welcome on her face. Even her nervousness was the kind to be approved of: it showed a proper sense of responsibility. Of course, it was Peter’s day, marking his debut as Wyatt’s housemaster. But, as everyone kept telling her, Eve was to be the power behind Peter’s throne. And she’d found the idea flattering as well as amusing because everything had seemed possible, exactly as it was supposed to on the first day of a new school year.

Arm-in-arm, she and Peter had waited brightly on the steps of Wyatt House, watching as the funeral procession of SUVs slunk up the chestnut avenue. In the car park, each new student stood nervously by the family car as parents unloaded luggage, already looking abandoned despite themselves. This batch of eleven year olds were children still, but only just, already lumbered with braces or out-size feet or with legs spindly from a recent growth spurt. Some jittered and fidgeted. Others waited with numb acceptance, as if stunned.

The next day, the older boys would return and take possession of the place. The dorm of sixty boys would reverberate with drumming feet and pounding music, whoops and yells echoing in the stairwells. There would be wrestling matches and water fights, the shrilling of the single payphone by the common room. But for now the place held on to the orderly hush of the holidays. The new boys murmured rather than spoke, cowed by the sense of occasion and its limitless scope for embarrassment. The parents kept up a cheerful patter, one or two mothers trying to hide a treacherous welling in their eyes.

Eve had felt a tenderness, then, for all of them. She had felt it towards even the most peevish of the mothers and pompous of the fathers, towards even the most sly-eyed of the boys. It didn’t last. Now, three years later, when she sees the littlest boys haul their luggage up the stairs … fragile, hopeful, trying to be brave … yes, she feels a pang. But she doesn’t trust it, or them, because she knows how soon they will begin to coarsen and harden like the rest.

Charm, of course, is what the public school system is known for. It’s the most expensive of polishes and burnished onto every Cleeve alumnus. But Eve thinks of the accumulated years here as like the cheap varnish on wooden desks, underlaid with the print of sweaty hands, obscene graffiti and wads of greying gum. It’s this gnarly carapace that lies beneath the gleaming Cleeve veneer. So when Eve glimpses – very occasionally – a trace of childhood softness in a student, she finds it unsettling. She doesn’t intend to be disarmed by these boys.

Cleeve is not for everyone. Full boarding is an all-embracing existence, and our staff are expected to involve themselves in every aspect of college life. But if you are excited by the chance to help shape lives, have energy and ambition, and are willing to throw yourself into our hard-working and vibrant community, we would love to hear from you.

Cleeve is not for everyone. Surely that’s the whole point, Eve had said to Peter, laughing, when he first showed her the ad. Cleeve is only for those who can afford it. And, even better, those who are born to it. Those who grow up in expectation of a life lived amidst velvety lawns and aged brick and confident masculine voices in wood-panelled rooms. The boys even sang about it in chapel. The rich man in his castle, / The poor man at his gate; / God made them, high or lowly, / And ordered their estate.

All things bright and beautiful indeed.

Eve should have paid more attention. She should have wondered about the tightening of that ‘all-embracing’ grip and at what point it might leave one gasping for air. But the warning was lost amid a flurry of enticements. Everything was generous – Salary! Accommodation! Benefits! Access to outstanding sports and leisure facilities, a rich and varied cultural programme – all to be enjoyed in five-star scenic surrounds. And then there was her husband’s face as he read and re-read the advertisement. Peter looked hopeful, yes, but also stern with purpose. The slackness of the last few months was suddenly gone, and he was handsome again. He’d had his call to arms.

Long before Eve came to Cleeve, she knew it intimately.

The Lake. The Lawn. The Hall. Simple words, as from a child’s storybook. The Avenue. The Chapel. The Clock Tower. Words that assumed the unshakeable authority of an archetype.

These words and the landscape they possessed (all three hundred acres of it!) had been the backdrop to the best years of Peter’s life. He’d said this to Eve not in a burst of nostalgia, but as an admission of pain. As the only child of a depressive alcoholic and his explosively volatile wife, school had been Peter’s only escape. A lost boy, he had found sanctuary at Cleeve. There had been a kindly housemaster, to whom he still wrote regularly; a cricket coach who helped him channel his rage into sportsmanship. He had been uplifted by the friendships and anchored by the old-fashioned value system. ‘Cleeve saved me,’ he said simply. ‘It protected me. Sheltered me. It believed in my best self.’

Peter knew his privilege. He knew that in a different setting the bewildered child he’d been would have grown up to be an irredeemably broken, perhaps dangerous, adult. That’s why he spent the early years of his teaching career in schools where many of his students came from homes blighted by poverty and chaos, or worse. He sincerely believed that the ideals of the public school system – the honour code, the respect for authority, the veneration of fair play – could raise both the standards and spirits of schools without any of the resources of a place like Cleeve.

But Peter, with his earnest face and guileless smile, his soft RP tones, was easy prey. In the classroom, he was faced with indifference or rebellion – and indifference was the more relentless of the two. In the staff-room, he was met with weary tolerance. A naive idealist of a conservative bent was, at best, a curiosity. At worst, he was a Tory stooge. Either way, Peter’s colleagues were not prepared to waste their near-exhausted energy on coaching him in survival tactics. Night after night, he’d come home to the cramped Kentish Town flat he shared with Eve and his face would be grey with exhaustion, his shoulders slumped with defeat.

The irony is, she was the one who pushed him to go private.

‘The world’s full of unhappy kids from broken homes – in all sections of society. You know that better than anyone. If you want to make a difference it shouldn’t matter where you do it.’

And then an old school pal passed on the news that Wyatt’s was looking for a housemaster and sealed both their fates.

Public schools were alien territory for Eve. She’d grown up in a bog-standard 1930s semi in the bog-standard suburbs of a bog-standard Midlands town and had never met anyone truly posh until she went to university. There, she and her friends would occasionally recoil from a honking pack of floppy-haired boys in red trousers, cashmere blondes braying at their sides. The wider student body regarded them as exotic irritants, but Eve could tell these people didn’t mind being the punchline to a joke. Why should they? Their birthright was predicated on having the last laugh.

Peter was not like this in any case. He was twenty-eight and Eve was thirty when they met. Eve’s previous boyfriends had been scruffy and argumentative, displaying the assorted chips on their shoulders like badges of honour. They were men who travelled adventurously and worked creatively; the more untrustworthy ones described themselves as feminists. She was introduced to Peter at a house party, where her friend pointed him out as ‘the world’s only Tory sin-bin teacher’. He was sandy and freckled, solidly built and attractive in a way that suggested bracing walks on wet hillsides. Not her type. And yet …

Despite Peter’s diffidence, he had an old-fashioned courtliness that Eve was secretly rather thrilled by. When he looked at her, his happiness was unselfconscious and open for all to see. His decency made her feel protective, a better version of herself.

Eve’s parents were dead. They had both died within a year of each other while she was at university – her father of cancer and her mother of an epileptic seizure not long afterwards. She told Peter on their first date that she was an adult orphan, trying to sound wry rather than self-pitying, but he had taken her hand in his and his own eyes were wet. He understood. When his old headmaster had died, he told her, he’d gone to the funeral and wept like a child, not just out of grief, but from the guilt of knowing that when his own parents passed he would be dry-eyed.

Peter’s parents still lived in the same ramshackle Salisbury house he grew up in, still entwined in a knot of mutual loathing; Peter and Eve’s visits there were as brief and infrequent as decorum would allow. Cleeve was the closest thing Peter had to a family home, and on their first visit, six months after they married and the day before Peter’s final-round interview, a part of Eve wondered why it had taken him so long to introduce her.

Certainly, he was nervous. He’d had anxiety dreams about the application process, and she’d heard him mumbling unhappily in his sleep. ‘It’s been so many years. I hope I’m doing the right thing,’ he said more than once, brow furrowed. ‘I hope this isn’t going to be a mistake.’ And she felt a rush of tenderness towards him.

As they drew near to their destination, Peter apologised for the local town, whose quaint olde-worlde centre had been swallowed up by an ugly shopping development and boxy estates. The road narrowed as they left the desultory outskirts behind and then, just a couple of miles further on, the woods began. The breeze pushed gently through the heavy trees, their closeness oppressive even in early summer. It was easy to miss the plain white sign between two stone posts: Cleeve College. Now the dark wall of trees had mown grass at its feet, a pristine lawn lining either side of the road until it curled over the Bridge and became the Avenue.

Everything was as Peter had described. The wide sheltered bowl of the playing fields. The stately red-brick mansion crowning the hill. Sunlight melting against the Chapel windows, the sonorous tolling of the bell in the Clock Tower. Even the students, seen from a distance, seemed to have a scholarly sense of purpose as they to-and-froed. Eve realised her sense of recognition wasn’t simply because of Peter. It struck her with new force how much institutions like Cleeve have become part of the English collective unconscious: whatever one thinks of them, everyone inherently knows what they are like. ‘Are you still frightened of the Clock Tower ghost?’ she asked, and Peter looked at her in surprise. How did she know? And Eve had laughed. Places like Cleeve always have a Clock Tower ghost.

Admittedly, the boarding houses weren’t so picturesque. They were mostly 1930s institutional gothic, with the exception of the sixth-form girls’ dorm, a modern block at the far edge of the campus. Wyatt’s had prime positioning near to the Hall; the housemaster’s quarters was a large annex, with three bedrooms and its own generous garden. Peter and Eve stayed there overnight as guests of the incumbent housemaster and his wife, who were retiring after eleven ‘wonderful, wonderful’ years.

In her naivety, Eve didn’t realise that their chatty kitchen supper was an unofficial part of the assessment process. It was probably just as well, because when she was nervous she could be abrasive. That night, however, the usual pleasantries flowed. ‘You’ve made a lovely family home,’ she said to their hostess. ‘It must be a great place for children.’ Eve didn’t mean anything particular by it, but husband and wife exchanged archly approving smiles and Peter blushed over his potatoes.

To change the subject, she asked about the washing line of lace panties she’d spotted strung between two trees on the Lawn. The housemaster’s wife had rolled her eyes. ‘It’ll be one of the leftovers from Hazard Night.’ Eve knew, hazily, what Hazard Night was – Peter had described it as a night of pranks once exams were done. She would come to look back on those leftovers as an omen, yet another of the warning signs she’d been so wilfully blind to. Wisps of lace fluttering among the leaves. A spill of bright paint along the ground. A blow-up doll, deflated and mangled in the mud. But – ‘I always knew it was a mistake letting girls into the sixth form,’ said their host, shaking his head with mock solemnity. ‘Place has gone downhill ever since.’ And they’d all laughed.

Girls aside, little appeared to have changed since Peter’s school days, though their tour took in the new facilities for science and sport. These additions had been expensively designed to maintain visual harmony within the eighteenth-century parkland and were named in honour of the Old Boys who’d funded them or had otherwise distinguished themselves. The Clitheroe Centre for Science and Technology, an oval structure set around a paved quad, was thus linked to the modern languages block by a covered walkway named Havod’s Walk. Jack Clitheroe had made a fortune in biotech; Maurice Havod had been a nineteenth-century explorer.

Later, Eve learned that the boys had rechristened these structures in line with the iconic simplicity of other landmarks.

The Clit and the Slit.

ALICE

I think I knew from the start that the new beard at Wyatt’s was a hopeless case.

(Beards are what the boys call the campus wives. Gogs – as in pedagogues – are the teaching staff. God is the name for my father, the chaplain. Fishface is what they call me.)

I’d been roped in to help on the Winslows’ first Arrivals because the kitchen was short-staffed and so Pat B – head of catering – asked if I’d lend a hand at Wyatt’s welcome tea. These teas are always served in the housemasters’ gardens, and although the kitchen staff do most of the baking and serving, it’s a tradition that the housemaster’s wife makes her own contribution. When Mrs Winslow unveiled her Tupperware boxes of gingerbread men, she flushed defensively. ‘I’m not much of a cook,’ she said, attempting a laugh, ‘but icing covers a multitude of sins.’

The biscuits were lavishly smothered in pink and blue frosting, presumably an approximation of the school colours of claret and navy. It must have taken her hours, putting in the little currant eyes and those tiny little silver balls for buttons. Anyway, the gingerbread gave her away. Not because the biscuits were blackened and misshapen and tasted like burnt sawdust, or because they were more appropriate for a kid’s birthday party than a public school induction. It was because she was already resenting having had to make them. It was obvious from the stiffness with which she got them out of the box. Later, I watched her mingle with the parents and boys, making self-deprecating remarks over her tray of mangled little men, and I thought: I give it a year.

I don’t know. Maybe I didn’t think this at all. It could just be hindsight. After all, who could have possibly predicted the Winslows’ tenure would end with two dead bodies and a tabloid sex scandal? And even that was only the half of it.

My father was one of the old-timers who’d been at Cleeve since Peter Winslow’s schooldays. He’s known as God because he looks like one in an old-master painting, with his flowing grey hair and lordly eyebrows. And his clothes do billow as he walks. But the nickname’s not an accolade and it’s not particularly affectionate, either. Other school chaplains promote Jesus as everyone’s big brother, his arms always open for a celestial hug. Their Jesus is as matey as he’s omnipotent. But the God of my father is the Cloud of Unknowing variety, and gets cloudier by the year.

Anyway, Pa remembered Peter Winslow. ‘Sad and angry at first, like a lot of the boys from difficult homes,’ he said, after such a long pause I thought he wasn’t going to speak at all. ‘Then keen and grateful. A little fervent. I thought he might fall hard for religion, as it happens. His type often do.’

I waited for more. But, as is usual with Pa, it wasn’t forthcoming.

Anyway, there they were: Mr Winslow, tanned and freckled and Tigger-ish, and his narrow, dark wife with the guarded smile. She was easy to spot among the Cleeve mothers, who are generally variations on a theme of Princess Di in mummy mode. The new wife was too plainly dressed for that and a bit too long in the face, maybe, for prettiness. Still, I could tell the boys were bound to jerk off to her. Eve Winslow was attractive enough for that.

The boys don’t jerk off to me. I’m a fixture of the place in the same way Pa is – but I’m more of a curiosity than an institution. Like the Hall gargoyle with the painted red nose. Or the ever-present smell of weed in the passage behind the Laundry.

My mother died when I was born, which if I was a different kind of girl would make me tragic and interesting. Here I am, raised by an ancient priest in an ivory tower, amidst a sea of blue-blooded testosterone. A squalling baby, flailing my fists in the Chapel vestibule … A squat toddler, pissing all over the Lawn … A moony ten-year old, dawdling along the Avenue …

A dour teenager, trudging back and forth from the bus stop in my cheap school uniform. Flat-chested, goggle-eyed, my mouth permanently downturned. Fishface.

‘It will be so nice for Alice to have some other girls on campus,’ one of the beards had exclaimed brightly at a faculty barbecue, shortly before the debut of the Monstrous Regiment, which was what some of the staff – only half-joking – had christened Cleeve’s first intake of female students in a hundred and sixty years.

‘There are girls at my school,’ I’d mumbled.

‘Yes, but this will be a very different sort of girl,’ said the beard. I think it was Mrs Riley, from Hawkins House, the latest in a long line of campus busybodies who had tried and failed to take me under their wing. ‘More of a kindred spirit, don’t you think?’

I was eleven at this point and the oldest campus brat after Mrs Riley’s own boys (both Cleevians, thanks to the generous staff discount on fees). A couple of the younger kids went to a private prep the other side of town. Meanwhile, I had attended the local state primary and was about to start at St Wilfred’s, the big comprehensive in town. My enrolment was assumed to be some quixotic gesture of my father’s (What Would Jesus Do? Send his children to the comp!). Actually, it was my choice.

Quite a few of my classmates also have parents who work at Cleeve. Or else uncles and aunts and older siblings. Cleeve is one of the biggest employers in these parts. But the locals aren’t teachers. They’re cleaners, laundry maids, dinner ladies, groundsmen. They’re the people who looked out for me as I was growing up. They let me tag along, do odd jobs and ask stupid questions. Put plasters on my knees when I fell down the Library steps, saved me an extra helping of chocolate pudding.

This is why I’m tolerated at school. I’m not a posh twit like the Cleevians who strut through the town centre on Saturday afternoons, taking up the entire width of the pavements, sucking up all the oxygen in the shops and cafes. No. But I’m not a townie, either, living as I do in a Hansel and Gretel cottage on the school estate with my dad, the weird vicar. At school, I am known to be clever and assumed to be odd. Back at Cleeve, meanwhile, I’m just … odd.

I knew from the start that having more girls around wouldn’t make any difference, at least not to me. Two or three times every term bus-loads of girls are imported from neighbouring public schools for socials in the Hall. These visitors, I observed, uniformly wore crushed velvet sheaths that barely skinned their arses and all had huge quantities of hair which they were constantly flicking about into lopsided quiffs. And they were always pawing each other, mouths nuzzling at each other’s ears. Breathy whispers, breathless giggles. An occasional shriek of hilarity or disdain. As they tottered out of the coaches, I’d watch them peep out at the waiting Romeos from under their silky manes, some coy, some malicious and all with the same sort of pretty-kitten face. They were as alien to me as the swarm of scuffling, swaggering males I’d grown up with. More so.

The first year’s intake were treated like celebrities. That was inevitable. But they were like celebrities who had suffered some kind of public fall from grace. Sure, they were coveted and venerated and gossiped about … but also somewhat despised. ‘Desperate virgins or mad slags’ was the verdict at St Wilf’s and maybe they had a point, because why else would these girls be pioneers? It can’t have been for the academics. Cleeve is what’s known as a ‘solid’ educational establishment, which essentially means that Oxbridge offers aren’t in great abundance.

Anyway. After five years of lady sixth formers the novelty’s mostly worn off. I watch them, sometimes, sunning themselves on the Lawn or idling by the Lake, and they’re not a part of the landscape yet. They’re too aware of the effect they’re having, or trying to make. I don’t envy them. It looks exhausting.

EVE

For her first few months at Cleeve, Eve commuted to her job in London four days a week. It was a slog, no doubt about it – first the bus, then the train for an hour, finally the Tube. But she liked her work as a copywriter at a small liberal think-tank, and her boss was accommodating. And though the days were long, and the hours she spent travelling were generally cramped and unpleasant, she felt her heart lift as she took her first steps through the glimmering, whispering arch of the Avenue.

Soon, of course, the nights drew in. But even then, Eve had loved to see the trees rise like plumes of smoke against the waning light. Never having lived in the countryside before, she was quietly amazed by the vastness and gentleness of its nights. She used to dawdle outside of Wyatt’s, taking a moment before going in to look at its grid of lit windows like an opened-up Advent calendar. She would listen to the hiss of the showers, music from competing stereos, the laughter. Someone might be practising a violin or flute, and a stammer of Mozart would turn into a ripple, then a soar of sweetness through the dark. That was the point when Eve would push open the door to the Private Side – it was never locked – and there would be supper, kept hot in an actual Aga, from the school kitchens.

True, she and Peter saw very little of each other. Peter’s day started before seven and usually finished around eleven, when he did a final check on the boys, and by which time Eve – exhausted from her commute – was already in bed. In addition to Peter’s housemaster duties, he taught a reduced timetable in his subject, history, and coached cricket on Saturday afternoons. There were sports fixtures and socials and cultural outings to be chaperoned too.

Eve told herself they just needed to settle in. The assistant housemaster, a gawky twenty-something who lived in a tiny flat at the top of the building, would gain in confidence and Peter would be able to delegate more. He’d stop volunteering at quite such an enthusiastic rate. He was still the New Boy, she reasoned, looking to prove himself.

Then Eve fell pregnant. It was not an accident, exactly, but it was certainly a surprise. Her morning sickness was violent and lasted most of the day; quite early on, it was obvious the travel would be impossible, never mind the job. Eve didn’t know anyone who ‘telecommuted’: by Christmas, she was officially unemployed.

Never mind, Peter told her. Cleeve was a wonderful place to raise a child: she’d said so herself. Why not take a year or two out to have the baby and enjoy motherhood on her own terms? Then she could look around, hopefully find something local, or maybe even retrain. They’d work it out.

They decided to keep the sex of the baby a surprise, but Eve was secretly convinced she was carrying a girl. When Milo was finally torn out of her, in a furious, frantic birth, her disappointment that he was a boy was something she worked to hide; at the beginning, she even hid it from herself. It might have been easier if he’d taken after her. There were people who looked at Eve’s slanting dark eyes and sallow skin and assumed some intriguing ethnic mix (if so, it must be a very distant ancestral throwback). Milo, however, was pure Peter. He was stolid, freckled, with a frank, open gaze.

‘An angel baby,’ said the health visitor, for Milo was from the start contented and plump. The first months, which everyone told her were the hardest, were the easiest for Eve. She took simple pleasure in her baby’s swaddles of fat, in his miniature velociraptor cries, the vinegary tang of his excretions. Even once Milo was on solids, the smell of his shit was a secret delight. She would press her nose to his wiggling backside and breathe in through the nappy the warm reassurance of his stink.

Motherhood changed when Milo was about eight months old. He would no longer entertain himself or stay safely put when placed on the floor. His three naps a day shrank to one. He wanted her, desperately, all the time. To rattle shakers and turn cogs and stack rings; to remove items from cupboards and turn pages of books. Whenever she left the room he exploded into howls of primal anguish. One morning Eve felt tears prick her eyes and realised she was, quite literally, crying with boredom.

Eve had always found other people’s children tedious or faintly alarming. She had assumed this changed once you had your own. She’d quite liked the idea of a child, or at least assumed she did. Peter, meanwhile, had longed for one. ‘He’ll make the most wonderful dad,’ people kept telling her, and this had reassured her when faith in her own maternal instincts faltered. But Peter was already a parent: to sixty teenage boys. Somebody was always crying or sick or fighting, playing pranks or on the verge of a breakdown. Somebody’s parents were always on the telephone.

Soon all of Eve’s time was spent waiting, waiting, waiting for the day to pass. The long hours had no landmarks except chores; when she did them, she felt resentful; when she neglected them, the house filled with a depressing slurry of toys and laundry and half-eaten food.

Worse, she had the lurking dread that she herself would never outgrow this phase – that from here on she would always find her child a burden. She looked into Milo’s eyes, and the bright expectancy of his gaze was frightening. The development of likes and dislikes, of moods and personality, all these things a parent rejoices in … they made her heart quake with love, yes, but they were also the terms of a new imprisonment.

She couldn’t shake off the feeling that somewhere, somehow, a terrible mistake had been made.

‘I think it’s a mistake,’ said Nancy Riley righteously, over coffee in Eve’s living room.

Cleeve’s latest bid to ingratiate itself with the local populace was to open up the school swimming pool for family swims on Sunday mornings. It was the hot-button topic du jour but Eve found herself distracted by a stain on the wallpaper just above Nancy’s head. It was rust-coloured, in the shape of a spider, and its position meant it appeared to be squatting on a blowsy pink rose. Their predecessors had be-sprigged the house in Laura Ashley-style florals, and although there was a redecoration allowance, Eve and Peter had agreed to put off home improvements until Milo was of a less destructive age. Milo was now nearly three and Eve was still staring at the same faded spread of fat, smug roses. But the spider-stain was new. Or was it?

It took an effort of will to turn her attention back to her visitor.

‘Sundays are so special at Cleeve,’ Nancy was lamenting. ‘Convivial yet quiet. It’s when school life feels the most intimate, don’t you think? All that will be spoiled with strangers tramping all over the place – those dog walkers in the woods are more than enough to contend with. There’ll be litter too. And,’ she said darkly, ‘I dread to think what will end up in the water.’

‘Mm.’ Eve found it hard to believe the purity of the pool was under threat – not when one considered the pustule-laced adolescents who usually marinated in it. ‘Do you know the First Lady’s view?’

The First Lady was Mrs Parish, the headmaster’s wife. She was cosy and diminutive, with round pink cheeks and twinkling blue eyes. Uptight parents, and fathers in particular, immediately softened in her presence. Eve had soon learned that the twinkle was actually a chip of glittering ice. It was rumoured that nothing official at Cleeve happened without her say-so.

‘Oh, Madeleine’s very supportive publicly, of course. Privately I’m sure she feels the same as we do.’ Nancy deferred to the headmaster’s wife in all things, but Eve suspected she chafed a little under her sovereignty. Nancy herself had the appearance of an attractive squirrel: bright-eyed and toothy with bristling reddish hair. The more helpful she was, the more squirrelly she became.

And Nancy had been exceedingly helpful to Eve, especially when Milo was first born. She’d held a welcome tea-party for Eve and another one close to her due date and had been generous with baked and knitted goods, not to mention advice, once Milo was born. It was she who’d prompted Eve to put Milo’s name down for the ‘only acceptable’ nursery in town. And she’d helped Eve get her current job – working part-time in the archivist’s office.

Since then, she had been assiduous – or relentless, depending on how you looked at it – in involving Eve in extracurriculars. Game nights. Charity bakes. Supper parties. Eve would have felt beholden in any case, but she had a nagging feeling that Nancy was positioning the two of them as particular friends. She was only five or six years older than Eve but had recently waved the youngest of her two boys off to university and was, Eve could admit in her more charitable moments, probably feeling somewhat at a loss. Meanwhile, Eve was mourning her old friends back in London, who, on the increasingly rare occasions they met up, seemed to want nothing more from her than smutty and amusing anecdotes about life in her ‘posh Borstal’.

Nancy didn’t only have updates on the swimming pool wars: a new head of Classics had been appointed. ‘Gabriel Easton, the name is. He’s terribly grand and an actual Cambridge don. He’s written several books. Quite a coup for the school.’

‘This man left Cambridge for Cleeve? Why?’

‘Apparently his wife wanted a change of scene. Nobody’s met her yet – she’s a bit of a mystery. Let’s hope she’s not one of those snobby bluestocking types.’ Nancy gave a toothy smile.

Eve had never considered herself an intellectual, but she found it frustrating how determinedly the faculty wives set themselves apart from anyone – and especially women – of even modest academic ambition. There were only three female teachers, two of whom lived out and one who taught (Music) alongside her husband (Geography), who was in every way her whiskery fuss-pot twin.

Eve thought of her old friends again, with their ooh-err jokes about matrons and fagging. She wondered if Nancy had come up against this too. Perhaps that’s why she and the other women here huddled so determinedly together. They were like forgotten colonialists in some unfashionable backwater of the Empire, congratulating each other on their good works and frontier spirit. Meanwhile, the natives went on about their business, completely ignoring them. Or possibly fomenting revolt.

The students are revolting! Eve had a hazy memory of scenes from If …: of floppy hair and starched collars and public school boys with machine guns, insouciantly mowing down the establishment from the school roof. They should remake the film, perhaps, but put the teachers and support staff on the roof instead – the wives could lead the charge. Now, that would be subversive.

‘What are you thinking about, Dolly Day-Dream?’ Nancy asked.

‘Firing squads,’ said Eve, and went to fetch the shortbread.

ALICE

The day the Eastons arrived was a significant one for me, in any case, because it also marked my third meaningful encounter with Henry Zhang.

Henry was one of the recent wave of Hong Kongers who’d been packed off to British boarding schools by parents anxious about the upcoming handover of the territory to China. There were a smattering of such students at Cleeve, but they seemed resigned to their foreignness, which was of the intrinsically unglamorous sort. Their shoulders were permanently slumped and their eyes were anxious; the furtiveness with which they spoke to each other in their native tongue only seemed to confirm their alien status. Henry Zhang, however, was different. One of his grandfathers was English, which helped; then he was captain of the cricket team, which helped even more. Plus he was six-foot tall with cheekbones that could cut glass. Once, I overheard somebody refer to him in passing as ‘the Yellow Peril’, and one of the other boys had drawled, ‘Yellow? Nah, that dude is golden.’

Still, he didn’t start off that way. When Henry first arrived, he was bespectacled and skinny, wearing an obviously second-hand uniform. This represented everything the two alpha male types on campus were not. Type Ones had lions’ heads, all tawny manes and gnashingly bright teeth. They captained sports teams and were a regular feature of both the school prospectus and the Bystander pages of Tatler. Type Twos were druggy and piratical, with baggy clothes and shadowed eyes. They were permanently on the verge of expulsion. Both types were referred to by their peers, without irony, as legends. Even in his golden age, Henry was more … circumspect.

Our first encounter was in his first term at Cleeve, which was the spring term of Henry’s and my third-form year. I’d seen him being dropped off at Wyatt’s, and the only reason I noticed him was the same reason everyone else did – because his mother, a very small and very exquisite Chinese woman, was 1) bundled up in a slightly woebegone fur coat instead of the usual cashmere, and 2) sobbing loudly and uncontrollably while hanging on to his neck. Few boys would have recovered from this in a hurry, and especially not some Hongky joining Cleeve halfway through. I suppose I might have felt sorry for him if I’d bothered to think about it.

Anyway, exeat weekend came up and the school abruptly emptied. I love exeat weekends even more than the holidays. During the holidays, the place is pimped out to language schools or music festivals or drama courses, and throngs of strangers with clip-boards are endlessly traipsing about. Maintenance work steps up and something is always being noisily built or demolished. But on exeat weekends nothing much happens. It’s as if the bricks and lawns and trees exhale a long, slow breath. The dorms are dark at night, and the paths and passageways are mostly empty except for shadows and a flurry of leaves. Best of all, hardly anyone’s around to use the swimming pool.

Swimming’s my thing. I started late – I was nearly seven when the rowing coach took pity on me and taught me alongside his four year old on Sunday afternoons. It’s thanks to him I have good technique. And, OK, I’m not strictly allowed to be in the school pool by myself, but I know the codes to get in, and the staff are generally fine to look the other way.

This particular Saturday, I let myself into the pool just before four. It was a late January afternoon, dank and cold, and the sky outside the windows was leaden. I hadn’t bothered turning on the main lights, so most of the illumination came from the pool, which shimmered a chemical turquoise. I was cruising up and down, luxuriating in the easy roll of my shoulders and hips. Catch, pull. Flow. Breathe. I came up for a pause at the shallow end and rubbed the steam from my goggles. That’s when I realised there was somebody – a boy – a student – one of the Asians – standing by the side.

He was in his navy school trunks, a white towel slung around his shoulders. He cleared his throat. ‘Hi. Hello. I, uh, thought we had to wait for the lifeguard?’

His voice echoed off the tiles. It was cut-glass, but also slightly old fashioned somehow.

I shrugged. Rudely. I was pissed off by the intrusion.

We looked at each other for a moment, each clearly wondering what on the earth the other was doing there. I saw a quiff of black hair and strong black brows. Reflected water dappled his face: not yellow, not yet tanned to gold. Ivory. He was frowning a little, trying to work me out. Or maybe he was just struggling to see without his specs.

Whatever relative or friend he was supposed to be staying with for the exeat must have fallen ill or had some kind of emergency, and he was still too much of an unknown to be scooped up by one of the other boys. I didn’t care. The swimming pool’s probably the one place in the world where I don’t get self-conscious. I like the sleekness of my body in my sports costume, the way my straggly mouse hair is tucked safely away, and my skull feels hugged by my swimming cap. And I know how well I move through the water. With grace, with strength. He was the interloper here, not me.

Perhaps he sensed this. He blinked. ‘You know, uh, you’re a really good swimmer.’

‘Yeah. Thanks.’ I spread my hands out in the water. Was this boy going to swim too? Or was he just going to wait and watch me until the lifeguard they’d found for him turned up? The dim lighting, the humid warmth of the air, made our solitude oddly intimate. Water rippled suggestively. Around us, there was a sense of pipes and filters thrumming away. The boy made an awkward gesture, and I realised he didn’t know what to do either.

He cleared his throat for a second time. ‘I’m Henry, by the way.’

‘Alice.’

‘You look familiar … I’m sorry … have we …?’

I smiled. ‘I’m the child of God.’

Now he looked really confused. I guess he hadn’t yet picked up on my father’s nickname. I bit back a spurt of laughter.

I was fourteen and had, up until then, always been indifferent to Cleeve boys. The lions, the pirates. The beastly and the nerdy and the nice-but-dims in between. The boys at school, too, with their gelled hair and tracksuits, their quick eyes and surly mouths. But now I looked back at Henry Zhang – at his long, smooth body, at his hair and his skin. Ebony and ivory. Soon, I knew, he’d get over his hesitancy. He’d stop clearing his throat before he spoke. He’d fill out, learn how to compensate for his foreignness and his second-hand clothes. Soon he’d build up some ease, then some popularity, and he’d disappear into it.

What was I waiting for? I pushed off, swimming down the lane at a furious rate. Let him look at me. I wasn’t Fishface – I was a water nymph, a mermaid. Daughter of a sea god! But when I came up for air again, the boy had gone.