3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WS

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Sixteen-year-old Chrissie’s first love is a girl.

But it’s the eighties, and she fears rejection from her rural community, so her relationship remains secret.

When her friend vanishes, Chrissie bears her heartache alone.

Decades later, her long-lost love resurfaces, but all is not as it seems. It takes a global pandemic and a brush with death to spark the resolution Chrissie craves.

Heartsound is a tale of unspoken truths, broken promises, almost-forgotten dreams, and hope.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

Heartsound

Clare Stevens

Published by Inspired Quill: March 2024

First Edition

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental. The publisher has no control over, and is not responsible for, any third-party websites or their contents.

Content Warning:

This title contains mentions of the following: Queerphobia, Hospitalisation, Death of Parent, Terrorist Attack (off-page), and Drug & Alcohol Use.

Heartsound © 2024 by Clare Stevens

Contact the author through their website: https://clarestevens.com/

Chief Editor: Sara-Jayne Slack

Proofreaders: David Smith & Peter Smith

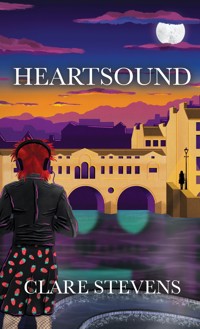

Cover Design: Rebekah Parrott (www.roseandgracedesign.com)

All Rights Reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner.

Paperback ISBN: 978-1-913117-23-8

eBook ISBN: 978-1-913117-24-5

EPUB Edition

Inspired Quill Publishing, UK

Business Reg. No. 7592847

https://www.inspired-quill.com

Praise for Clare Stevens

Blue Tide Rising

A debut novel that deftly steps between gritty reality and magic realism with an agility that many more seasoned writers would envy, this is a book that has a beating heart within its fascinating central character.

– Matt Turpin,Nottingham UNESCO City of Literature

A timely novel of mental health issues, of understanding when to cease blaming ourselves for other people’s actions, and of finding a safe home […] this novel is strongly rooted in a recognizably British reality so I think even readers who aren’t magical realism fans would enjoy this accomplished debut.

– Literary Flits

In a culture where staying ‘pure’ is still regarded as a woman’s ultimate virtue, in a system that prefers silence and secrecy to truth and justice; amidst a mindset that does not mind crushing a woman’s dreams if it feeds male entitlement, it feels novel to imagine that lives like Amy’s are getting redeemed somewhere out there. That voices like hers are being heard. That experiences like hers are being counted. Even if it is set in another land. Even if it is all fiction.

– The Hindu (Newspaper)

To JP, always my first reader. Thank you for the music.

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright Page

Praise for Clare Stevens

Dedication

Prologue

PART ONE: The Strawberry Girl

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

PART TWO: What Lies Within

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Chapter Forty-Seven

Chapter Forty-Eight

Chapter Forty-Nine

Chapter Fifty

Chapter Fifty-One

Chapter Fifty-Two

Chapter Fifty-Three

Chapter Fifty-Four

Chapter Fifty-Five

Chapter Fifty-Six

Chapter Fifty-Seven

Chapter Fifty-Eight

Chapter Fifty-Nine

Chapter Sixty

Chapter Sixty-One

Chapter Sixty-Two

Chapter Sixty-Three

PART THREE: Unboxed

Chapter Sixty-Four

Chapter Sixty-Five

Chapter Sixty-Six

Chapter Sixty-Seven

Chapter Sixty-Eight

Chapter Sixty-Nine

Chapter Seventy

Chapter Seventy-One

Chapter Seventy-Two

Chapter Seventy-Three

Chapter Seventy-Four

Chapter Seventy-Five

Chapter Seventy-Six

Dear Reader

Acknowledgements

About the Author

More From This Author

Prologue

24 March 2020

Stevie steals in by stealth. Through the back gate. Looking both ways to check for prying eyes. You can’t be too careful.

There’s an unseen menace out there. It’s everywhere. Even in the air.

An existential threat to the human race. As we cower, fearing death, the birds outside burst forth with life, louder than ever.

Stevie enters the garage, silently. I take a while to notice he’s arrived.

“How are you, darling?” Stevie blows me a kiss from a safe distance.

Just yesterday we were here, with Paul and Charlotte, drinking gin, beer and wine on our last night of freedom. Playing the juke box game, summoning Siri from his globular speaker placed in the centre of the table like a Ouija board. We played apocalyptical songs. The evening had a finality about it. The end of the world as we know it.

Stevie’s brought his own mug. It has a picture of the Welsh dragon on it and permanent coffee stains. I disinfect my hands, and fill the mug with a double shot of espresso from the machine. Stevie loiters in the garage, which isn’t, technically, in the house. The rules are hours old and already we’re bending them.

“Can we resurrect this?” he runs his finger in the dust along the edge of the table tennis table. Folded up to make room for all the boxes. “Could be the ideal lockdown pastime.”

I google the length of a standard table tennis table. 2.7 metres. Perfect for this thing called social distancing we’re all supposed to be doing.

“We’ll have to move the boxes.”

Stevie helps me shift them. “What’s in them? Why have they got dates on them?”

“It’s like my filing system. It’s all stuff from my life. Letters, photos, diaries You know, the emotional baggage you accumulate through the years.”

He picks up the biggest box. It’s made of heavy-duty cardboard, sealed in thick, black masking tape. “This one weighs a ton,” he says, squinting at the faded label with a date still visible. “Nineteen eighty-one must’ve been a heavy year.”

“I need to go through them, decide if anything’s worth keeping and bin the rest. I’m waiting for a rainy day.”

“Or a sunny lockdown day,” he says, looking outside to the blazing March sunshine.

Then he chuckles. “Christine Carlisle’s past in sealed boxes. I’ll help you if you like. Who knows what secrets they’ll unleash?”

I shake my head. This is something I must tackle alone.

PART ONE

The Strawberry Girl

I’m not ready to open the suitcase yet, the little pink case Nan gave me that was good for nothing else but storing letters – me being a rucksack girl. Instead, I dig out the framed photo of us all at Melcombe, taken the summer before we left. The class of ’81. Here we all are, in our navy and white uniforms with the red and gold school ties. There’s me and Claire in the middle, flanked by the boys. Andy, long and lean, still in his mod phase, opting for a razor-thin non-regulation black tie with his school blazer. The tie is knotted half way down his chest and slightly skewed. I think he’s trying to be Paul Weller. I’ve got cat-eye make-up, angular eyebrows drawn on in thick black pencil, and deep red lipstick. My hair, short and still dark from the remnants of black dye, is spiked up. Claire’s next to me, petite and pretty, pink streaks in her hair. And then there’s Mike, standing strong, legs apart, shoulders splayed, oozing testosterone. A bunch of hopefuls on the cusp of life. Whatever happened to all that youth?

I show the photo to Stevie. ‘“You look like a little Siouxie Sioux,” he says. That’s who I modelled myself on.

Chapter One

Hey Siri, play ‘Christine’ by Siouxie and the Banshees.

September 1981

I’m walking across the courtyard to the hotch-potch of buildings that make up Stoke College. I’m sixteen years old and on the brink of a new adventure. It’s the first day of term and the future’s looking bright, like the weather. Crisp, sunny, September.

I’m wearing the leather biker jacket my cousin brought back from New York with my fifties strawberry-print dress and docs. I’ve used the belt of the dress to make a head-band. I’ve got my retro leather satchel slung over my shoulder and my hair’s spiked up with orange mousse.

I missed the bus with the others because Mum had an urgent call-out this morning so I had to walk the dog. David, my brother, could have done it but he seems incapable of getting out of bed these days. It’s a two-bus journey to college. So now I’m late, and flustered, trying to remember the way to the common room, having only been there once when we came for the open day.

I’m smoking a rollup to steady my nerves, hoping I don’t get the legendary one pound fine for anyone caught smoking on college premises. I don’t usually smoke in the daytime, but these are exceptional circumstances.

Students in groups of twos and threes are approaching the buildings from various directions. I look around for familiar faces but there’s no-one I know. These people must all be from different schools. This day is just for us, this year’s intake, so everyone is new, I guess. But I’m alone.

I’m conscious of a couple walking near me on a parallel path. Both tall, beautiful and obviously moneyed. He has a Stray Cat quiff and wears an ankle-length black coat. She has long blonde hair with just the right amount of wave. They walk with confidence. They seem older. They have an air of sophistication.

I suddenly feel small.

There’s a shout from somewhere up above and everyone in the vicinity looks round. I see Andy and Mike framed in a window. They’ve opened it right out and they’re sitting on the sill. Claire appears between them and Ian behind her. Four faces, all mine. They whoop, and wave, then Andy dives inside and reappears with a giant speaker which he wedges in the window. It blasts out ‘Christine’ by Siouxie and the Banshees.

My song. The one that earned me the nickname ‘Strawberry Girl.’

I have a fleeting feeling that I’ve lived this scene before.

The tall girl with the long blonde hair looks from the faces in the window to me as the song bearing my name reverberates at volume across the courtyard. I have a sense of being noticed. Of being someone.

At this moment, I know I’ve arrived.

Stoke College, up on a hill just out of town, is a meeting of the schools. And in Bath there are so many schools, mostly private, each with its own distinctive uniform. It’s the college of choice for those of us from Melcombe Comp thought clever enough to go on to university. From Melcombe there’s me and Claire, Lisa Scott-Thomas, Andy Collins, Mike Fairfax, and the twins Ian and Sandy. (Oh, and four girls from the Knitting Brigade, but we don’t really talk to them.)

Our common room is in one of the grand old houses that form part of the complex. The room is massive. Someone said it used to be a ballroom. It has big bay windows and original fireplaces at each end.

As I enter, I see our lot have already colonised one end of the room, the end with the stereo. There’s vinyl spread over the tables along with copies of NME and Sounds. (We’re too cool for Melody Maker.) There’s a row of LPs lined up in the recess of the old fireplace. Someone’s even created a listening booth in the corner.

Andy’s brought in some of his avant-garde post-punk collection.

“Chrissieeeee,” they shout in unison as I walk in. Claire moves her bag and pats the sofa next to her. I sit down in the seat she’s saved for me.

Claire and I have stepped up together to sixth-form college. I’ve known her since I was nine when we bonded as best friends. Now, we sit side by side facing the room, flanked by our friends as other people, from other schools, take up the spaces in the room that will become their territory. There’s an energy in the place, part nervousness, part excitement. We’re at the start of something.

“What time’s Assembly?” asks Lisa, clutching her Blondie bag to her chest.

“It’s not called Assembly here. It’s induction,” says Claire, combing through her hair with her fingers.

“Induction – what’s that when it’s at home?”

“Posh name for Assembly,” I say.

The college is built partly on the site of an old entertainment complex, most of which has been knocked down to make room for the new block, but they kept the art deco cinema which is referred to as ‘The Theatre.’ This is where we go for our induction.

On the way, we stop at the notice board to scour the timetable of classes and a list of who’s doing which subjects. At Melcombe Comp, we could recite the register from memory. Claire and I were next to each other followed by Andy. It went, Christine Carlisle, Claire Cole, Andrew Collins. It’s strange to see the list of unfamiliar names. But somehow exciting.

“Aye aye, who’s this imposter?” says Claire. We are no longer adjacent on the list. There’s someone called Tara Clinton in between.

“How dare she?” I peer closer. “Whoever she is, she’s doing psychology.”

“Like you,” says Claire.

We arrive early at the Theatre, sit near the back and watch everyone file in. I nudge Claire as Dr Powell, the attractive music teacher, who’s also our head of year, appears on stage. We saw him at the open day and Claire said he was a good enough reason to apply.

He’s well known around Bath because he heads up various jazz bands, choirs and orchestras, as well as setting up a recording studio for aspiring college bands.

He’s wearing a dark suit with a black polo-neck jumper and slightly tinted glasses. Already he owns the stage.

“That guy’s just so cool,” says Claire.

“Ok, let’s play ‘Guess the School’,” I say, as groups of students arrive.

Claire stands up with her back to the seat in front of her to get a better view.

“Hayesfield,” she nods towards a bunch of girls with Banamarama hairstyles and ripped jeans.

“Oldfield?” I say as another group takes the seats below.

“Hmm. My money’s on Bath High.”

“What about this lot – they look posh?”

“Must be the Royal.”

“King Edwards,” I say, as a group of boys file into the row opposite. They’ve got that clean-cut, assured, rugby player look you’d expect from the place.

But Claire doesn’t answer. She’s staring at the boy at the end of the line and he’s staring back. It’s like a jolt of electricity has passed between them. I watch her face flush. I can almost hear her pulse pound, can almost feel the adrenaline shoot through her as Dr Powell taps the microphone to call the room to order.

“I have to know who he is,” Claire whispers as she sits down.

Already I sense I’ve lost her.

Powell’s speech, short and pithy, is lost on her now as she strains to see past me to the boy.

I’m closer, so I can get a proper look. The boy is short, but so is Claire. Good looking, granted, but he’s our year and I thought we agreed we were only interested in older boys. I thought we decided people our own age were immature.

“I have to meet him,” she says as we all file out.

She doesn’t need to wait long. The next evening, there’s a welcome party in the hall. Like grab-a-fresher night at university. A party to suss out the talent and size up the competition.

Claire and the boy gravitate towards each other like nobody else exists, then slip into the shadows. I glimpse them later at the back, snogging to Adam and the Ants while the rest of us dance. They snog all night. They leave together.

And now, it’s never just Claire any more. It’s Claire-and-Simon. Andy calls them “the couple who share a tongue”.

Chapter Two

A record sleeve from a seven-inch single. I lift the disc out, and run my fingers across its dusty grooves. It’s warped, but even if it wasn’t, I’d have nothing to play it on. Instead, I have the great juke box in the sky that is Siri.

Hey Siri, play ‘Echo Beach’ by Martha and the Muffins.

September 1981

We’re stacking up the singles on the stereo and it’s my turn to choose. I’ve brought in a copy of Echo Beach that I picked up from the ex-chart singles section in the shop next to Reg Holden. It’s playing now as the tall couple I saw on the first day enter the room. The girl clocks the music, glances at her quiffed companion and does a little understated dance move as they pass. I’m standing by the stereo and she looks directly at me. “I just love this song,” she says. And I feel a little swell of pride, like a teacher or someone in authority has complimented me.

They haven’t graced the common room until now, although we’ve spotted them driving up to college in his vintage open topped car, the girl wearing dark glasses and a scarf wrapped around her head like Jackie Onassis. “He drives a Triumph Stag,” said Mike. “There’s money there.”

We all know they’re from Kingswood. You can tell. There’s something lofty and confident about them. Of all Bath’s many private schools, Kingswood is the most exclusive. Kingswood kids are rare at college as they have their own A-list sixth form. Tara’s here to study psychology, a new A-level subject this year – most schools don’t offer it.

Tara wears skin-tight jeans on legs that go on forever and an expensive-looking shoulder-padded jacket. Her long blonde hair is perfectly crimped, probably done at a hairdresser’s, not plaited while wet, then moussed up, which is how the rest of us do it. She has a chiselled face and a pretty, upturned nose. She looks about six foot tall. She walks with style and self-assured elegance. Like a model.

When she walks in, all the girls hate her and all the boys want her.

“Jason, look at this!” she stops by the old fireplace, but she’s not looking at the records we’ve piled up in the recess, she’s admiring the architecture as she runs her finger over the marble top. She’s not from round here. She has an accent I can’t quite place.

“What period is this?” she asks her friend, who’s examining the frieze carved into the plaster.

“Georgian. I’d say early eighteenth century. Queen Anne design.” He has a smooth, velvety voice.

Tara and Jason glide through the room like a piece of performance art, then settle at the far end, the opposite end to us.

This first week is a whirl. Boundaries give and loyalties shift, and there’s a sense, particularly for me, as I watch my best friend disappearing into the sunset, that life will never be the same.

On Saturday, Claire brings Simon round to ours. They sit at either end of the sofa, for once not snogging or touching. Looking at them side by side it seems inevitable that they should be together. They look the same. Same build. Same symmetrical perfect faces. Him slightly taller than her, slightly darker hair. Like bookends, my mum says.

I feel a little lost without my best friend by my side. But it frees me up to be my own person. To hang out with the boys. To pursue my love of music. To meet new people.

I next see Tara the following week in psychology. She sits at the front and answers intelligently in her strange accent. Is she Irish? It’s different from Nan’s Cork accent but has a kind of lilt. She knows about Gestalt theory and Melanie Klein and Jung’s collective unconscious. I sit at the back with Lisa Scott-Thomas from Melcombe, who after two weeks drops out and transfers to Bath Tech. So the third week into term Tara and I are thrown together for a practical. Two oddballs without a partner.

“Are you Irish?” I ask, still trying to suss the accent. And because it’s something to say.

She looks at me down her chiselled nose and wrinkles it slightly.

“I’m part Canadian,” she says. “I was born there.”

“Oh really, how long have you been over here?”

“This last time?” she asks, like I’m supposed to know she’s lived here more than once. She then tells me she’s spent her childhood jetting between London, Hong Kong and Vancouver, never staying more than a few years in each. Now her parents have split up and she’s living with her mum in Bath.

I don’t know what to say. Her life is oceans apart from mine. We spend an hour not connecting as I wait for the session to be over so I can get back to my mates.

The next day I have a free period and decide to spend it in the common room. There’s nobody much around. I’m heading for our end of the room when I see Tara, sitting with her back to me on one of the comfy chairs in the middle, legs draped over the armrest, body twisted, head in a book. Even like that she looks a picture of poise and elegance. I’m about to walk past when she looks up and says, “Hi Chrissie.” Despite the awkwardness of yesterday, I feel a little shiver of pride. She’s remembered my name.

“Hi Tara.”

“How ya doin’?”

“I’ve got a free period. I’m supposed to be doing my French essay. How come you didn’t do French? Don’t you speak it over there?”

She shakes her head. “Wrong part of Canada. You’re thinking Quebec.”

Now I know she’s Canadian, I can clearly hear it in her accent.

“Anyway, I suck at languages,” she adds.

I laugh.

She nods towards the chair opposite. “Why don’t you sit?”

I sit.

“So what’re you reading?”

She shows me the book. Jean-Paul Sartre’s Nausea, English translation. It has a surrealist picture of a beachscape on the front cover.

“We’re doing him in French,” I say. “Did you know his eyes looked in two different directions?”

It’s the most unsophisticated thing to say to someone like Tara. But, to my surprise, she laughs.

“I did not know that. I’ve learnt something today. Maybe I can learn more from you than from the tutors.”

“I’ll try and come up with another gem of knowledge for you tomorrow,” I say, racking my brain for a way to keep the conversation going.

One of the knitting girls comes in, nods at me and scuttles off to a table in the corner.

“Did she go to the church school?” Tara asks.

“No. She went to our school, Melcombe Comp, but she didn’t hang out with us. We called her and her mates the knitting brigade.”

“Do they knit?” Tara’s voice is loud.

I keep mine muted. “They look like they ought to.”

Tara laughs out loud then. “I thought they might be convent girls.”

“Nah the Catholics have their own college. They don’t mix with the likes of us. And anyway, Catholic girls are all sluts – you’d be surprised.”

Tara laughs again. “I’m learning a lot from you, Chrissie.”

Why do I get a thrill when she says my name?

The door swings open and Andy, Mike and Ian appear. “Oi Strawbs! What’s going on?” says Andy when he sees me sitting somewhere different. Then he clocks Tara and the shock is palpable. The three of them swagger over. “Who’s your friend?” says Mike, jerking his head towards Tara.

“Mike – Tara, Tara – Mike,” I say. Tara merely says hi, then returns to her book.

Not a prayer, I think, as I watch Mike trying to big himself up. The three of them saunter off back to our end of the room.

“Why do they call you Strawberry Girl?” Tara asks when they’ve gone. “Your hair’s not strawberry blonde anymore.”

I’ve recently henna’d it a deep dark red.

“It’s a line from a song by Siouxie and the Banshees called Christine.”

She shrugs. “Punk kinda passed me by. You’ll have to educate me.”

When Claire-and-Simon show up, I leave to join the others. But a part of me feels pain at parting. And a part of me can’t help looking over at the back of Tara’s armchair.

“What you doing hanging out with her? Didn’t think she’d associate with us,” says Mike.

“Tara’s cool,” I say. “You’re just miffed ’cos she doesn’t fancy you.”

“Is she going out with that poof with the quiff?”

“You mean Jason?” I say. “Dunno. Think they’re just mates.”

“Mike!,” says Claire. “You smitten? She’s obviously out of your league.”

Chapter Three

A photo of us all leaning on the wall by Parade Gardens. Probably on our way to some gig. There’s Andy, man in black at the back, hair glued into vertical spikes. Apart from Ben who’s wearing a cap to hide his bald spot, we all have gravity-defying hair. I’m dressed in a square-shouldered man’s jacket I got from Oxfam and my old red and gold school tie is in my hair. My eyes, as usual, are outlined in thick black kohl. They look huge and rounded. I wish kohl had that effect on me now.

Hey Siri, play ‘The Velvet Gentleman’ by Erik Satie

September 1981

I’ve known Andy all through school, right from infants. He’s another West-Melcomber, like me and Claire. But it’s only since coming to college that we’ve had much time for each other.

He was a grubby kid with a runny nose who turned into a nerdy, spotty teenager with a lock of dark hair that fell into his eye. He developed a head jerk, almost a tic, to shake the stubborn bit of hair away from his face. He grew at an exponential rate, so he was always about a foot taller than everyone else, then started rounding his back to compensate. In 1978 when we were fourteen he turned punk overnight. He shaved his hair at the sides and glued the rest of it up into a Mohican which he dyed with red food colouring. His mum said all his pillows were pink. Then a year later he went mod. Short hair, long sideburns and a Parka. Now, in 1981, his hair’s black and gelled up, goth style. As the day wears on the gel wears off and once again his hair flops into his eyes. These days, he dresses all in black. Black drainpipe jeans with a studded belt worn loosely round the hips. And a black outsize shirt – that’s his signature attire. Despite his long bendy back he’s somehow standing taller, like he’s finally grown into his height. And I have to admit this is the best I’ve ever seen him look. Plus I’m developing an interest in music. And where music’s concerned, Andy’s your man. He’s somehow made his way to the cutting edge of the music scene. His ability to play the keyboard and to string together a lyric has got him into a band, and now he’s studying the subject for A-level.

As well as being a meeting of the schools, Stoke College is a meeting of the subcultures. There are goths, punks, post-punks, new romantics, plus still a few Cindy girls. Claire and I used to be very scathing about Cindy girls, with their bleached blonde hair and penchant for pink. Now, Claire’s starting to resemble one herself. She’s toned down her hair. Gone are the pink streaks and it’s now in a neat bob. Although she’s a natural blonde. Of course.

We maintain our spot by the stereo, but our circle’s widened to include a few people from other schools, the common factor being music. One of these is Ben, who – at the age of seventeen – is already balding. What hair he has is wispy and ginger and gelled up in the centre of his head so he looks like TinTin. But Ben’s cool. His older brother lives in London and writes for the NME and Ben got a byline on a review he wrote when The Psychedelic Furs played Bristol Locarno. I feel an instant affinity with him. There’s something reassuring and uncomplicated about Ben. All he’s interested in, all he ever wants to talk about, is music.

*

It’s Saturday, and Andy and I get off the bus at Bear Flat to pick up Ben, then walk into town for some serious record shopping. Ben knows the places to go for all the best bargains. First stop’s the shop next to Reg Holden with the ex-chart singles. I pick up a copy of Ghost Town by The Specials for fifty pence. Then it’s Southgate where we spend half an hour browsing the fabulous first floor of John Menzies, before heading up to Woolworths, Owen Owen and the one on the corner of the Corridor. We take in Milsoms, WH Smith and Duck, Son & Pinker – where Ben picks up an obscure punk album by a band even Andy’s never heard of. Then it’s up to Walcott Street market for bootlegs. On our way back we cut through the narrow street past Jaberwocky café, where there’s a tiny bookshop underneath the art gallery. I’ve never been in before, it sells mostly art books but they have a few records in the window, so we wander in. One of Mum’s social worker colleagues, Mo, is in there talking to the hippy guy who runs the place.

Mo is loud, and from London, and the only real-life lesbian I’ve ever met. She stands out in a crowd. Today she’s wearing bright orange leggings that hug her ample thighs, and a gigantic man’s jumper. Her girlfriend, whose name I don’t know, is in the shop too, browsing while Mo chats. She’s like a smaller, quieter, darker-skinned version of Mo. She’s wearing a khaki combat jacket with badges all over it that say things like ‘Make Love Not War’. I try to fade into the background so I won’t be recognised, but it’s impossible in a shop this small.

“Christine!” Mo hails me in her booming voice. “Just the person! Want a Saturday job? They need someone here!” Rob, the owner, interviews me there and then while my mates hover. He tells me I can start next weekend.

So I land myself a job, and at £10 a day it pays better than Sainsbury’s, which is where most of my friends end up working.

The place is fusty, low-ceilinged, and scruffy, with wonky floorboards and floor to ceiling shelving. My induction is laid back, like my employer. He demonstrates how to use the till. It’s as antiquated as the books and shuts with a satisfying ding, like the toy cash registers I played with as a child. He gives me a tour of the shelves so I can familiarise myself with the stock.

“Here we have the big fat art books,” he says. “This section is mostly art history. There’s society and politics along the back wall and photography books at the end. Things are mostly alphabetical. If someone comes in and asks for something you can’t find, take a phone number as we might be able to get hold of it.”

As well as books, there’s a single rail of clothes – mostly tie-dyed skirts and beaded kaftans that smell of petunia – and a tiny record section.

After showing me the kettle – which lives behind a purple curtain at the back – Rob says “How about some music?” puts a record on the turntable then leaves me to my own devices until lunchtime.

The music is classical, and atmospheric. I look at the sleeve. It’s ‘The Velvet Gentleman’ by Erik Satie. It’s not my kind of music, but there’s something haunting about it. Something dreamy.

I sit at my counter by the window, serve a couple of Japanese students and a university lecturer, and talk to a man who’s made the journey from Glastonbury for a specific avant-garde art book we don’t have. At one point there are four people in the shop and it feels crowded.

After a couple of hours, there’s a lull, so I put the record on again and dip behind the purple curtain to make myself a coffee, when the bell on the door signals customers. I hear a familiar voice saying “Jeez, Jason, I love this place, It’s so shabby.” I emerge from the back room to see Tara and Jason. They’re both studying art history, so of course they would come here.

“Wow, it’s you!” says Tara. “Do you actually work here?”

I swell with pride.

Chapter Four

A list of names on a yellowed A4 sheet. Four names picked out in orange highlighter. Christine Carlisle: French, Maths, Psychology. Tara Clinton: Art History, English, Psychology. Claire Cole: Biology, Physics, Chemistry. Andrew Collins, Maths, Physics, Music.

September 1981

After our conversation in the common room and our encounter in the shop, I don’t mind being paired up with Tara in psychology. In fact, I relish it. She sits at the back with me now in the seat vacated by Lisa Scott-Thomas. And I’m throwing myself into the subject, learning new stuff – seminal stuff.

The teacher is a Ms not a Miss or Mrs and she prefers us to call her by her first name – Imogen. She heads up the college debating society and she sets us off on a project to debate the merits of psychoanalysis versus behaviour therapy. Tara and I have been picked to lead the debate, on opposite sides.

Tara – perhaps because she’s North American – has grown up around the idea of everyone having their own psychoanalyst. She thinks you need to delve deep into people’s childhoods to get to the root of the problem.

I – perhaps because my mother is a social worker – believe that approach is a money-spinner that fosters dependency and keeps people in therapy. Behaviour therapy works, and it works fast.

We hold the debate in the Theatre at lunchtime and have invited the rest of our year. Tara and I sit on chairs at either side of the stage, with Imogen between us holding a stop-watch. It’s like we’re on Question Time or something.

I clock a line of my mates in the front row, rooting for me.

I kick off.

“Psychoanalysis has its roots in Freud, and we all now know him to be a fraud! Freud the fraud!” I pause for effect, liking my alliteration.

“Plus,” I add. “He was obsessed with sex. Everything, according to Freud, has to be about sex.”

Tara cuts in. “Everything is about sex.”

Titters from the audience.

“Chrissie, continue,” says Imogen.

“That’s as may be. But, Freud’s version of sex was at best naïve, at worst downright chauvinistic. Girls, do we really have that penis envy thing? Boys, how many of you can honestly tell me your deepest desire is to screw your mother?” More laughter. Louder this time.

I’m enjoying this. I use words that people can understand and I get kudos for saying the word “penis” on stage. I know there’s a certain prejudice against Tara – with her sophistication, her use of academic words and her alien accent – and right now, I’m playing on that.

Now it’s her turn.

“Freud is irrelevant to this debate,” she says. “He may be the father of psychoanalysis but the work has progressed hugely since his time.” She reels off a list of names, dates and academic studies.

“We now know that the causes of neurosis are complex. All behaviourism does is treat the symptoms. That’s like trying to cure cancer with a common cold cure.” Her turn to alliterate. “The only way is to cut the cancer out, right? It’s the same with a sickness of the mind. You have to get to the root cause.”

I have the final say and I use it to my advantage.

“There are cases in the States of people hooked on psychoanalysis. They’ve been going to see their therapist for twenty, even thirty years and they still haven’t got to the root cause! All that’s good for is the therapist’s bank balance. You could say this approach has fostered a nation of neurotics!

“I really hope we don’t go down that route in the UK. What we have in behaviour therapy is a cheap, effective, fast-working treatment that works! Which would you rather have?”

Imogen declares the result a draw.

“You won that debate hands down,” says Andy afterwards.

“It was a draw!”

“You won. She hid behind big words and statistics but you spoke to the people.”

I get the feeling he doesn’t like Tara. I’ve heard he and Mike tried to chat her up at the bus stop but she wasn’t interested.

Although opposites in the debate, the project draws Tara and I closer together. She won’t come to our end of the common room, preferring to sit in the ‘library’ end, which is quieter, so I divide my time between my mates from Melcombe and the other musos at our end, and my exclusive chats with Tara. We take to staying in the classroom after psychology, finding a quiet corner of the refectory or going to the library where we work and whisper together. We also go up to the art room on the top floor of the new block to see her friend Jason. He’s studying art and he practically lives up there, surrounded by large canvases.

“Why won’t your posh mate sit with us?” asks Mike, when Tara heads for the other end of the common room.

“We’re not good enough for her, obviously,” says Andy.

“She’s actually quite shy.” I say, but nobody believes me. How can someone so outspoken in class and confident with adults be shy? They can’t work her out. And I can’t work out what it is that makes me feel uncomfortable mixing her with my old mates. I have a feeling of jumping between two worlds and sense a need to keep them separate.

Tara remains someone I see at college, though. Evenings and weekends are taken up with hanging out with the old crew, going to gigs, exploring music. For now, our home lives stay unconnected.

Chapter Five

A cassette box. Labelled in my own writing with the wordsPsychology: interviews – Chrissie and Tara.It still has the tape inside. I turn to my local community Facebook site. Anyone still possess a cassette player? In among the laughing emojis and ironic comments there’s a message from some kind person offering to drop one off. I have it within the hour.

At first, I think there’s nothing on the tape, except the white noise of the cassette player whirring. I turn the volume up in case whatever is recorded is so quiet I can’t hear it. Suddenly there’s a loud click then my sixteen-year-old voice, deafening and stifling laughter, reels off the questions on our psychology interview sheet.

Chrissie: So, Tara, tell me about your childhood?

Now comes Tara’s voice, quieter. She must have been sitting farther from the mic. If we even had a mic.

Tara: My childhood was a mess. We were always on the move. We zig-zagged between continents. I was born in Canada. Then we lived in Hong Kong ‘til I was ten. When I was seven they sent me to boarding school in England.

Chrissie: On your own?

Tara: Yeah. On a twenty-one-hour flight. We stopped at places like Bahrain, Delhi, Calcutta, Karachi, and Tehran, and then Rome or Frankfurt for refuelling. With the time difference It felt endless. I had a sign around my neck saying “unaccompanied minor”.

Chrissie: Like Paddington?

Tara: What? Oh yeah.

Laughter.

Chrissie: What was boarding school like?

My accent was distinctly Somerset then. I rolled the ‘r’ in ‘boarding school.’

Tara: Pretty grim. Bullying was institutionalised. Prefects had too much power. You had to toughen up to survive. I survived.

Chrissie: How d’you think that affected you?

I’m pretty sure I’m going off script here, but I’m glad I did – this is fascinating.

Tara: It made me build a shell around myself, to shield my emotions. It gave me the ability to be two people. On the outside, calm and in control, on the inside, a gibbering wreck.

Chrissie: So what brought you to Bath?

I pronounce it Barrff.

Tara: After my parents divorced Mum moved back to the city where she grew up.

Chrissie: What’s your relationship like with your mother?

Back on script

Tara: We hate each other.

Nervous laughter on the tape.

Chrissie: You can’t mean that?

Tara: Chrissie, I do.

Chrissie: Ok, final question. If you could have a magical power, what would it be?

Tara: I’d be able to fly. Like a bird. Across oceans. Across continents.

Chrissie: So you wouldn’t have to sit on a plane with a label ‘round your neck?

The tape stops then, abruptly. Presumably Imogen called time. Then it’s my turn, with Tara asking those same scripted questions.

Tara: So, Chrissie, tell me about your childhood.

Her voice is languid, and she lingers over my name.

Chrissie: Boring compared to yours. I’ve always lived in Melcombe and I’d never been out of England until last year when we went on the French exchange. It’s just me, my mum and my younger brother at home.

Tara: What happened to your father?

Chrissie: Oh. Sorry, I didn’t say. He died when I was nine.

Tara: I’m so sorry to hear that. How did losing a parent so young affect you?

There’s a pause on the tape. Maybe I’m upset. Tara says “take your time.” I come back sounding slightly muffled.

Chrissie: It was still a shock even though he’d had cancer for a long time. Mum’s a social worker and she works funny hours, so me and my brother got farmed out to Nan’s house after school or to one of my aunties. I’ve got aunties all over the place as Mum’s one of seven sisters. Mum’s social worker friends all piled in and tried to counsel me and David. We had lots of therapy!

Laughter.

We went to this really awkward family counselling thing. Me, David, Mum and Aunty Shauna sat in a circle in a tiny room. Aunty Shauna started crying for no reason, then spent the next five minutes apologising. Then it all went quiet and the therapist said “Silence. What’s happening in this silence?” and I caught David’s eye and we both started giggling. Mum told us off later and we never went again.

Tara: It didn’t work then?

Chrissie: It made us laugh. So maybe it did.

Tara: Thank you Chrissie. Now tell me about your relationship with your mother.

Chrissie: It’s normal I s’pose. We argue.

Tara: Ok Chrissie, now to our last question – what’s your superpower?

Chrissie: Well I already fly, so it won’t be that.

Tara: What d’you mean you already fly?

Chrissie: Not with wings, like a bird. I kind of levitate, looking down on everything. I fly all around Melcombe. Sometimes as far as Bath.

Tara: So you, like, detach? In your dreams?

Chrissie: It’s not a dream. It’s pre-dream.

Tara: Like an out of body experience?

Chrissie: Sort of, but I’m not looking down at myself. I fly to other places and look in on other people. They never know I’m there. It started when my dad was dying. I wasn’t allowed to visit, but I looked down at him on his hospital bed. Mum was sat on a grey plastic chair next to him, holding his hand. There was a nurse with frizzy ginger hair and a sparkly pen in her pocket who came over and said something, then Mum knocked a glass of water all over the bed. Three days later my dad died in those exact same circumstances.

Tara: So it was a premonition?

Chrissie: Kind of. It happened a lot around that time. I’d see something, then it would happen. Claire and I cashed in on it by writing people’s horoscopes. We called ourselves the Claire Voyants and charged them ten pence a go!

Tara: You’re telling me as a child you were running a fortune-telling racket? How enterprising!

Chrissie: Yeah. You could write any old rubbish and they believed it. Then one time I predicted a bus crash involving a girl at school’s mum and it actually happened. After that the teachers closed down our little enterprise. But I carried on seeing things. My Aunty Nessa who’s psychic says it’s a special gift. Mum thought it was a delusion caused by the trauma of Dad dying. The counsellor said it was dissociation. But it’s not, because when you’ve got that you feel like you don’t exist. I know I exist.

Tara: I’m very glad you exist, Chrissie.

Chapter Six

Another cassette case. This one has “Sounds of Canada” written on the spine in precise, sloping handwriting. The writing is faded, but I can still make out most of the titles on the cover. Neil Young, Rush, Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen. The case is empty.

September 1981

“Anywhere in town we can get a decent coffee?” Tara pronounces it “carfee”. So instead of going to the common room after psychology we walk down into the city centre. But coffee shops – apparently common overseas – haven’t yet made it to the UK. We stick our heads into a quaint Bath tea-room where the waitresses dress as French maids, but although they do seventeen blends of leaf tea they don’t, evidently, do anything that qualifies as decent coffee.

“We could have tea instead,” I say. She wrinkles her nose. “I don’t get this English obsession with tea. Let’s go to the apartment.”

She leads me through town to a street around the corner from the city’s famous Pulteney Bridge, and stops outside a four-storey Georgian townhouse. She looks up, at an open first floor window, and says, “My mum’s in.” There’s a certain resignation in her voice, a weariness that I find hard to fathom. Inside, we climb a wide staircase covered in plush plum carpet. She pushes open the door to a first floor flat. A whiff of cigarette smoke meets our nostrils, mixed with the smell of wood-polish and the sort of incense aroma you get in hippy shops.

We enter a hallway where there’s an antique mahogany sideboard with a pile of glossy magazines on top. In the corner, hanging on a wooden coat stand, there’s a fur coat that looks real and a patchwork suede seventies-style jacket. We walk through into a dining room where a woman sits, smoking a cigarette and reading a magazine. The woman looks up. She has thick, straight, ash-blonde hair in a long bob. Her face, expertly made up, has a bronze glow and no visible wrinkles. It’s hard to guess her age. She has full lips glossed in a dark rose, her eyelids blended in shades of brown. Her eyes themselves are grey, not brown like Tara’s. Something about them seems dead.

She balances her cigarette on the ashtray then rises to her feet. She’s tall, like her daughter. She wears a long white house coat with square shoulders, and cropped, black trousers. Her clothes look tailored and expensive.

She looks nothing at all like a mum.

“Mum, this is Chrissie.”

I sense Tara’s mother sizing me up, assessing my thrown together outfit and finding me lacking. She stretches out her hand. “I’m Grace, Tara’s mother.” Her voice is posh, English – unlike Tara’s – and husky. Her handshake is brief, barely pinching my palm with cool fingers. She doesn’t smile.

She strides over to a sideboard against the wall and picks up an airmail letter resting on the top. She carries it over to us, holding it by one corner as though it’s on fire, then hands it to Tara.

“This arrived,” she says.

“Thanks,” Tara takes the envelope. Her mother stands in front of her, waiting.

“I’ll open it later.”

Grace sniffs, then resumes her seat at the table, picking up her cigarette and drawing on it. She blows the smoke vaguely in the direction of the open window. Most of it trails back into the room.

Tara looks at me. “Let’s go to my room.”

Tara’s room is spacious. The full-sized double bed is huge compared to my single at home. There are no posters on the wall, just a framed painting of a girl. It looks familiar. I wonder if it’s by a famous artist. Possibly even an original. Her desk is antique mahogany with a green leather top, like something you’d see in a country house. There’s even a two-seater settee in the room.

She has a decent stereo, of course. Silver turntable, separate tape deck and amp, which sits on a sideboard like the one in the hall. I thumb through her records.

“Put something on if you like, but my taste’s a bit old school.”

Dylan, Leonard Cohen, Neil Young, Beatles, Stones, some early Led Zep. It’s like a cross between my mum’s and my brother’s collection.

I scrutinise her row of cassettes, and pull out a compilation tape which has ‘sounds of Canada’ written on it in neat italics.

“How about some music from your country? I don’t know many Canadian bands.”

“You must know Neil Young? He’s Canadian. So’s Leonard Cohen. And Rush. Oh, and ‘Echo Beach’ by Martha and the Muffins, You’ve got the single in the common room. They’re from Canada.”

I put the tape on. The deck responds to the lightest of touches, opening slowly. Everything is smooth. Not like my clunky music system at home.

“Come and sit down,” she pats the sofa next to her. I sit. She peels off the edge of the airmail letter and starts to read.

“It’s from my dad,” she says, lowering her voice. “Mum’s very bitter.”

She’s told me before, that her dad “ran off with a Chinese woman,” when they were in Hong Kong. I look over her shoulder and notice the letter is signed “Roger” not “Dad” and in a different hand “Aisee”.

“He always had women on the side,” she says. “He had this thing about oriental women. Mum calls it yellow fever. But this time he acted on it, left mum and married her.”

“And don’t you mind?”

She shakes her head. “It’s his life. I’d rather he was happy living apart from us than unhappy living with us. Aisee’s cool.”

“Is it true your mum’s a model?” So says the word on the street at college.

“Not like a career catwalk model, although she was once featured on the cover of Vogue. There’s a print of it in the hall. She was more like a, what do you call it, an It Girl? A Debutante? Do they still have those?” She looks at me as if for confirmation. I can’t help her as I know nothing about such things.

“Before she met my dad she hung out with London’s elite artists and photographers. She knew people like Lord Snowdon – you know, Princess Margaret’s ex? Dad took her away from all that. That’s another reason for her to resent him.” Tara makes it all sound so matter of fact.

The tape plays at low volume, which seems strange given the capacity of the machine and the size of the speakers.

“Can I turn it up?” I ask.

“A bit, but if it’s much louder, she’ll be in,” Tara nods towards the living room.

Sure enough, after a couple of tracks, there’s a tap on the door and her mother appears in the doorway, eyebrows raised, visibly disapproving.

“Hi Mum,” Tara sounds bright, but defiant.

“Would your friend like to stay for dinner?” Grace looks from one to the other of us as we sit on Tara’s sofa.

“I don’t know. Would you, Chrissie?”

“I’d love to, but only if it’s convenient,” I feel gauche and unsophisticated in the presence of the two of them.

“It’ll be my pleasure to cook for my daughter’s guest,” she says, still not smiling. “It’ll be ready in about an hour. We don’t normally eat this early but I’m going out.”

I’m not sure whether she really wants me there or not.

“She’s a good cook,” says Tara after Grace has gone.

The aroma of cooking soon mingles with the cigarette smoke and fragrance of essential oils.

We have red wine with dinner, brought over from Bordeaux. The first course is chicken cooked in wine, with perfect new potatoes and green veg, served on plain white plates, bigger than the ones we have at home. It’s like a meal you’d get in a restaurant, not something your mum cooked.

Beyond asking me what subjects I’m doing and what school I went to before – she curls her lip slightly when I mention Melcombe Comp – Grace seems uninterested in me. I detect a hint of boredom when I answer. She becomes more animated over the wine, however, and starts to tell me things about herself.

“I used to live on Sloane Street.”

I’ve heard of Sloane rangers. This must be what they’re like.

Tara picks up the plates and takes them into the kitchen. Grace lights a cigarette which she holds in the hand not clutching the wine glass.

“I had so many men before I met Tara’s father,” she says. “I was in demand.”

“Really?”

This doesn’t surprise me. What does surprise me is that she sees fit to impart this information to me – someone she’s only just met.

“So many men,” she says, sighing a little. I wonder if she used to smile back in the days when men were abundant.

She turns to Tara, who’s reappeared with the pudding – three individually served chocolate mousses, in glasses with stems and frosted sides.

“What did your father have to say?”

“Not a lot. They’ve been back to Hong Kong. Aisee’s mother’s ill.”

Grace winces slightly, like she has toothache, then turns back to me.

“Are there any good-looking young men at college?”

“Um, dunno really. Maybe a few. What d’you reckon Tara?”

It occurs to me I’ve never talked to Tara about boys.

Tara laughs. “They’re boys, mother, not men.”

“Tara’s friend Jason’s probably about the best looking,” I say.

“But he’s queer,” says Grace.

This is news to me.

Tara bristles. “You say ‘gay’ mum, not ‘queer’.”

Tara’s mother frowns. “He’s no good to us, whatever he is.”

“Simon’s good looking,” I say, to brighten the mood. “But short. And taken, of course. Snapped up on day one of college by my friend Claire.”