7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

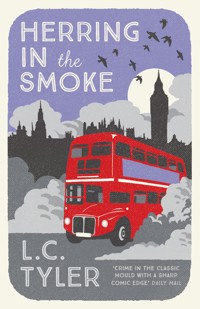

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: The Herring Mysteries

- Sprache: Englisch

Roger Norton Vane is dead. Twenty years ago he went for a walk in the Thai jungle with his partner and never returned. After years of wild speculation and fruitless searches, finally his death is to be made official and somebody will inherit his accumulated wealth. Ethelred Tressider, crime writer and Vane's biographer, attends the memorial service, but little does he expect to find himself talking to Vane himself, apparently returned from the dead. Chaos ensues and while trying to complete the biography it becomes clear that many people wish the man calling himself Vane had stayed dead, and that his anecdotes had died with him...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 353

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Herring in the Smoke

L. C. TYLER

In memory of Uncle Len

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

It was at his own memorial service that I first spoke to Roger Norton Vane.

I had arrived slightly late, being less used than I once was to London’s Byzantine one-way systems and parking regulations. By the time I had found a more or less legal place to leave my car within walking distance of the church, I was uncomfortably aware that I might not get a seat. Vane had been well known and (at least with the general public) popular. I ended up being ushered into a pew at the very back, along with an amiable old gentleman dressed incongruously in beige cotton trousers, open sandals and a heavy, navy-blue overcoat, who was equally late but either unaware of the fact or not much bothered.

At first he ignored me, craning his neck one way and another to see who occupied the seats in the many rows in front of us. Occasionally he nodded, as if approving of what he saw. Now and then he pulled a face. Once he rather theatrically held his nose. Then finally he turned in my direction.

‘Just flew in this morning,’ he said, at a volume that suggested the whole church deserved to know. He jabbed with his thumb at his thick woollen lapels. ‘I’d forgotten how cold it was back here. Isn’t March supposed to be spring or something? Daffodils? Easter bonnets? Fluffy little lambs, waiting to be turned into chops? Flew over with not so much as a sweater in my suitcase. Certainly nothing for this weather. So, I asked the taxi driver to stop off at’ – he named an outfitter who had gone out of business some fifteen years before – ‘and the damned fool said he’d never heard of it. Took me to Marks and Spencer. Said they had loads of overcoats there. Actually they’d already switched to their summer stock. Still, they had this little number in pure English wool on the Reduced rail. Quite natty. Made in Vietnam, oddly enough. Funny, when you think about it. Vietnam. Right next door to us.’

‘Ah …’ I said. I glanced nervously towards the distant lectern in case things were about to begin. I wasn’t sure we had time for a long explanation about how he got his new coat, or why Vietnam was just next door to Islington, and I didn’t want to find myself in lone mid-conversation as an otherwise respectful silence descended.

My companion, however, was clearly not worried that he was in danger of interrupting anything important. He looked knowingly at me and then uttered something in a language I didn’t understand – lilting, musical but at the same time slightly harsh.

‘Sorry?’ I said.

He repeated it with a grin. ‘I live in Laos, you see,’ he added. He pronounced it ‘Lao’, without the final ‘s’, which I’ve always regarded as a bit of an affectation; but maybe not if you actually live there and speak the language, as he apparently did. ‘Decent little country, all things considered. Still twenty years behind Vietnam and at least forty behind Singapore. But comfortable enough these days. And well run. No hint of democracy, thank goodness. No human rights to speak of. Absolutely top place. Do you know it at all?’

I smiled apologetically and looked again towards the far end of the church, but there was no indication that anyone had plans to begin on time. A very famous writer, who was due to speak at the service, was leaning against a pew, checking his notes in an unhurried way. Vane’s niece, whom I had got to know well over the past month or so, was standing and chatting to guests. It was all remarkably relaxed; but this was, I kept having to remind myself, not a funeral but a joyous celebration of the life and work of Roger Norton Vane. There was no need for solemnity. It seemed impolite not to introduce myself to my talkative neighbour.

‘I’m Ethelred Tressider,’ I said, holding out my hand.

The gentleman in the glossy new overcoat responded with a remarkably firm handshake.

‘But I usually write my novels as Peter Fielding,’ I added. ‘I’m a writer, you see …’

He shook his head. He hadn’t heard of me. I felt I was losing his attention.

‘And sometimes I write as J. R. Elliott,’ I added anyway. ‘Historical crime set in the fourteenth century. Maybe you might have …?’

He shook his head again. Sometimes people make an initial pretence, purely out of politeness, of trying to remember whether they’ve read one of my books; but his look made it crystal clear that he couldn’t be even remotely arsed. I decided not to enquire if he’d come across any of the lightweight romances I write as Amanda Collins. I had just turned back to my service sheet when he said something that I was sure I must have misheard.

‘Sorry,’ I replied, looking up, ‘I thought just for a moment that you said you were Roger Norton Vane.’ I smiled at my error.

‘No, that’s what I said,’ he replied.

‘You mean you’re some relative of the writer …’

‘No, I mean I am the person in whose honour today’s festivities are being organised. I am Roger Vane. The writer. Recently deceased.’

I looked at the photo on the order of service that I had been handed as I came in, and then at the gentleman next to me. I knew the photo well. I had actually supplied it to the organisers myself. If this was Roger Norton Vane beside me, he had aged considerably since the picture was taken. But twenty years is a long time.

‘You don’t believe me, do you?’ he asked.

‘I don’t know what to believe,’ I said. ‘It’s just that …’

‘You thought I was dead?’

‘Everyone thought that,’ I said. ‘That’s why we’re all here. In this church. It’s your memorial service. What I was going to say was: it’s just that I’m your biographer.’

‘Are you? You’ll probably be wondering what I’ve been doing for the past twenty years, then.’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘When writing the final chapters I did wonder a bit.’

‘Bet you did. So, I have a biographer now, do I? I’ve clearly gone up in the world since I died. Who did you say you were?’

I told him again. Just the Tressider bit this time.

‘Well, maybe not that far up,’ he said. ‘Were you the best they could manage?’

‘I’m not sure I was the publisher’s first choice,’ I said apologetically.

‘I certainly hope you weren’t,’ he said. ‘Still, we are where we are. We’ll need to have a chat. Properly. Now I’m back in the Smoke. I’ll have plenty of stories to tell you, and not just about my time in the East. Let the literary world tremble in its kitten heels. I could spin you a yarn or two about him … and her.’ His thumb indicated a prominent television presenter and the CEO of a big publishing house. Neither was actually trembling at that moment, but I appreciated that they might be soon. Like the rest of the congregation, they were tied up in their own conversations, exchanging platitudes, swapping lies about sales figures. Nobody had felt it worthwhile to listen to us – the loud-mouthed man in a blue overcoat and his tall but slightly nervous companion.

‘So you mean you’ve been in Laos for the past twenty years?’ I asked.

Roger Norton Vane gave me a broad smile. ‘There and other places. And unfortunately not quite as dead as everyone thought,’ he said. ‘They’re all going to look a bit silly, don’t you think? Everyone except you and me, Ethelred.’

He gave me a conspiratorial wink. Then, finally, the organ finally began playing and the human voices around us were stilled, one by one, as if by a vast wave rolling inexorably from the front to the back of the packed church. At the same moment the sun suddenly burst through the great stained glass window above the altar, sending a bright technicolour dawn into the chancel. We both turned towards the renascent glow, each curious, in our own way, to see what would happen next.

CHAPTER TWO

It had been twenty years before the memorial service that Roger Norton Vane had vanished without trace. Twenty years to the day.

Vane had, when I first came across his work, been a moderately successful writer of crime novels set in the nineteen fifties – which at that time just about qualified as historical fiction. Later the books were turned into a television series and his face became as familiar to the public as his well-illustrated covers. One of my reasons for believing that he had indeed now returned from the dead was that I recognised the voice – I’d heard it often on television and radio and, as guest of honour, at crime writing conferences. I told you that I’d never spoken to him, which is true, but I’d listened to him more times than I could recall. I started to read his books because everyone else was doing so and continued because they were genuinely very good – not pastiche fifties, but quirky modern novels that evoked the period wonderfully well. His rise seemed unstoppable. Then, quite suddenly and at the height of his fame, he had disappeared without trace.

He had gone on holiday to Thailand, with his then partner, Tim Macdonald. One afternoon they had set off from their hotel on a walk through the jungle. Adventurous though this may sound, the mountain forest path was in fact much used and well signposted. An averagely fit person could complete the circular route, as described invitingly in the hotel brochure, in just over two and a half hours. The path was surprisingly flat, for the most part an old logging road, hugging the contours of the adjacent slopes. Many walked it in trainers in the dry season. Both men were fit and more than capable of a gentle stroll of this sort. They had, according to the hotel, been advised to stick strictly to the trail, though Macdonald later denied that any such warning had been given. It was subsequently agreed by all that they had left at two o’clock and had a very adequate four hours of daylight to complete their circuit. Macdonald returned alone at quarter to five, saying that his friend had decided to continue a bit further alone, but should be back shortly. That was his entire explanation. Macdonald went to their room to take a shower. At five-thirty he came to reception to return the walking stick he had borrowed and to enquire whether his partner had shown up and perhaps gone straight to the bar. He hadn’t. The receptionist noted that Tim had a scratch on his face, which he claimed was from a thorn. Since there were in fact thorns in the jungle, the receptionist did not think to probe any further. With hindsight, he subsequently admitted, perhaps he should have done.

Later – very much later – the official enquiry into the matter established that a proper search did not begin until well after dark, for which Macdonald and the hotel blamed each other with equal enthusiasm. Hotel staff had retraced Vane’s journey, their small handheld torches casting a feeble light on the trunks of the huge, vaulting forest trees and none at all into the vast black expanses beyond. They were not helped by the fact that Macdonald was unclear at exactly which point the two had parted company, especially since the torch batteries were by that stage nearly exhausted and one liana-clad tree looked much like another.

A second attempt was made at first light, with every spare staff member – for the most part city-bred and unfamiliar with the scary green waste around them – now urgently scouring the jungle. The police were finally called in towards midday, over twenty hours after Vane and Macdonald had set out. The local chief superintendent would eventually tell the investigating committee that by then it was far too late – Vane had already perished or wandered well beyond the area they were searching. There were, he hinted, one or two scrawny tigers still in the area who might arguably have been looking for breakfast at a time when the police had yet to be alerted. The hotel manager counterclaimed that if helicopters had been deployed straight away, as he had frantically demanded over the phone, they could have covered the larger search area that the chief superintendent rightly referred to. In seven years at the hotel he had never seen a tiger. He said that poachers had hopefully shot the last of them years before. The one pictured in the brochure lived in Bangkok Zoo and was for illustrative purposes only. Both implied, as much as they dared, that Macdonald had been negligent of his friend’s welfare – that he should not have left him in the first place and that he should subsequently have been less amenable to the suggestion that nothing untoward had happened in the possibly-tiger-haunted jungle. He should not have gone to the bar and ordered a Singapore gin sling with fried cashew nuts on the side. Had bitter recriminations alone taken the investigation forward, Vane would have been located at once. But he wasn’t.

When three days of searching had come to a fruitless conclusion, Macdonald was briefly and very publicly arrested for murder and flown to Bangkok for questioning, the almost-healed scratch on his face now being regarded as incriminating in the extreme. His explanation that his friend had decided to continue alone was minutely dissected – to where would Vane have continued on a circular path, other than back to the hotel? Did Macdonald mean that he had turned back and Vane carried on round the path? Or did he mean that he had carried on and Vane retraced his steps? Or something else entirely? Macdonald seemed unsure which he meant, raising further doubts in the mind of the police. Why had he taken the walking stick to his room rather than return it immediately to the hotel desk? Macdonald conceded that he had cleaned it before returning it but said his intentions had been helpful rather than otherwise. Had he used it as a murder weapon, he argued, he would have thrown it into the jungle and risked being charged twenty Baht for its non-return.

These false and hurtful accusations, Macdonald later argued, caused the scaling down of the search at a critical time. He was eventually released without charges being laid and left for England early the following morning, a precipitous departure for which he was criticised by anyone looking to shift the blame from themselves. As it turned out, he could have stayed for another twenty years without being able to play any meaningful part in the investigation.

Of course, in the months that followed, there were countless sightings. A German couple, staying at the same hotel a few weeks later, reported seeing a man in the jungle, who had smiled and waved at them. A hat, not entirely unlike the one Vane had been wearing but possibly of a different colour, was found shortly after by somebody who had themselves accidentally strayed off the path, and vouched for the ease with which it could be done.

A girl in a bar in Bangkok said she had definitely served Vane a double Mekhong and Coke with ice and lemon, but she wasn’t sure when. He was seen getting into a taxi in Kuala Lumpur and getting out of one in Penang. He was seen crossing the road very, very carefully in Hanoi. He bought a newspaper in Hong Kong and told the vendor to keep the change, which was admittedly not a great deal. He won a large sum of money at a casino in Macao. He was most certainly seen, a year or so later, begging by the side of the road in Calcutta, wearing a blue T-shirt and green shorts with the logo of the Brazilian football team. He had a long conversation with a British pensioner on the beach in Galle, and definitely said that his name was ‘Vane’ or ‘Vine’ or ‘Lane’ or ‘Villiers’ or something very much like it – it had proved difficult to buy hearing-aid batteries of the right type in Sri Lanka. He bought a ticket at Wimbledon Tube Station and said quite specifically that he did not need a return, in spite of the saving he might have made.

The local Thai police treated each sighting with mild interest. They were aware that nobody survived more than a few days alone in the jungle and, if he was alive anywhere, it wasn’t on their patch. After six months, a team from Scotland Yard had the good fortune to be sent to Thailand to help the police with their investigations. They stayed as long as they could and were interviewed several times on local and international television. One of the policemen got sunburn and one contracted a sexually transmitted disease.

Then, finally, there was a genuine piece of evidence – the only one that would surface in twenty years. A fisherman at a beach resort was caught trying to sell a very expensive watch. It was inscribed: ‘To Roger, with all my love, Tim’. The fisherman was arrested and was triumphantly presented to the press, in handcuffs. He claimed, however, to have bought the watch from an Englishman who said that he didn’t need it any more. He was no thief, he said. He’d paid a lot of money for it – several thousand Baht – which he’d borrowed from a friend. A friend quickly emerged to confirm that he had indeed lent the fisherman money, so that he could purchase the watch at the bargain price the Englishman had named. The fisherman also found or purchased several impeccable witnesses to confirm he had been fishing, far out at sea, when Vane had vanished. After a while the suspect was quietly released, without handcuffs, to explain to his friend why he could not repay the loan in the foreseeable future. The watch remained in an evidence bag in a police station on the Thai coast, pending future investigations.

As the years passed, the sightings became fewer. The television series continued with new plots devised by various scriptwriters, as they would have done anyway. The old episodes were repeated. Sales of the books remained steady, especially with the new television-tie-in covers. Royalties piled up in a bank account. Vane’s reputation, in fact, remained high, fuelled in part by his thrilling absence. On the fifth and tenth anniversaries of his vanishing there were long pieces in the Sunday papers, speculating on what had happened, but coming up with nothing that was both credible and new. Tim Macdonald refused to be interviewed or even to appear on reality television shows. The fifteenth anniversary passed largely unnoticed. As we neared the twentieth, it was proposed that there should finally be a memorial service. And I was asked to write a biography, somewhat late in the day, to cash in on what the publisher hoped would be at least a brief renewal of interest in his books.

When I received my invitation to the service I almost declined it. It seemed strange to mourn for somebody I had never had a conversation with. But being his biographer (even though the book was far from complete) tipped the balance. I had to be there – not to lament his passing but, as the fashion now is, to celebrate his life and work. Especially when I had supplied the photograph for the order of service.

Thus it was that I was able to send the first tweet when it all kicked off. As Elsie later pointed out – one day it could be the only thing that I am still remembered for.

CHAPTER THREE

So, that is what I knew – no more, no less – as I sat beside a dead man in a church in north London, wondering if things would go well or badly.

On this last point, Vane himself seemed willing to keep an open mind. Hands in his pockets, he slouched in the pew and listened to the various tributes being paid to him. Occasionally he half-turned to me and nodded his approval, or he muttered ‘that’s complete crap’ or ‘I hope you’ve got the correct version of that story in your book’ or, more succinctly, ‘arsehole’.

Though his posture was that of a sulky teenager, I think on the whole he was enjoying himself. Few of us get to hear what our friends will say of us after our deaths and for the most part they spoke quite well of him.

It was not until Tim MacDonald took to the stage that I noticed he tensed a little. Vane frowned and leant forwards. Tim, now I had a chance to study him, was an undoubtedly good-looking man, who appeared to both possess and use a gym membership. He was slightly younger than Vane, but his hair was showing the very first signs of grey at the sides. He was, I knew, an illustrator of children’s books – successful enough in his own right and still occupying Vane’s old flat in Canonbury. I had never seen the flat because Tim had refused to cooperate in any way with the biography – it was one of the many reasons why the book was still not finished. He paused before addressing us, apparently half amused, half contemptuous of the packed church before him. Slowly he took out a single sheet of thick cream paper, which he laid carefully on the lectern. He took from another pocket a pair of bright-green reading glasses and put them on. He knew we’d have to wait until he was good and ready. What others had said was merely a build-up to this, the definitive verdict on Roger Norton Vane.

‘I hope you’ve got your phone handy,’ said Vane without looking at me. He was staring fixedly at Tim.

‘It’s switched off,’ I whispered. ‘They told us to …’

‘And you actually did?’

‘Yes.’

‘Switch it back on, then, because in about thirty seconds you’re going to need it,’ said Vane.

An elaborate cough from behind us hinted that somebody would rather listen to Tim than to us. I suspected that, whatever Vane had in mind, it might not go entirely well. But it was, and for once quite literally, his funeral.

I fumbled in my pocket and so missed the first few words that Tim Macdonald spoke. But I did catch what he said next. ‘Some might say that Roger Norton Vane was loved and loathed in equal measure …’ It was at that point that Vane finally broke cover. One moment he was there beside me. The next it was just an empty space.

I heard a sharp intake of breath from all sides. Then somebody said: ‘Good grief! Surely not? It’s actually him.’

When I looked up, phone at the ready, Vane was already striding rapidly down the aisle, blue overcoat billowing out behind him, bearing down on the man who had once been accused of murdering him. My tweet carried a picture of his back, about halfway to his intended target. Based on this rear view alone, it was just somebody walking quickly down the aisle – but the evident consternation on people’s faces made it clear that this was a novel and unplanned feature of the service. The picture was retweeted several thousand times before the day was out. (Seventeen retweets was my previous best.) Even today, if you google ‘blue M&S overcoat’ it’s one of the first images to come up.

Thus it was that the world first heard of Roger Norton Vane’s resurrection, and thus it was that the congregation were informed firmly but politely that they could all piss off back to where they came from. Tim Macdonald included.

‘Of course, it has implications,’ said Elsie. ‘You realise that, I hope?’

I had arranged to see my agent after the service because, as I’ve said, I am rarely in London these days and she had suggested a catch-up coffee, which we were now having. I noted that her inviting me had not prevented my paying. But Elsie had not suggested we went anywhere expensive, in case she accidentally stumbled into footing the bill herself. It had, it seemed, happened at least once before.

‘It’s very exciting,’ I said, passing Elsie the sugar. ‘I mean … a writer reappearing after a twenty-year absence. After years of speculating, we’ll all finally know what happened to him.’

‘It will certainly increase the sales of the biography,’ she said.

‘I hadn’t thought of that,’ I said.

‘No, you wouldn’t have. That’s why you have me as your agent. To think of that.’

‘Well, it’s a good thing, however you look at it. I can ask Roger all sorts of questions that had been puzzling me.’

Elsie nodded thoughtfully. ‘Of course, we can’t now do the hatchet job we’d planned.’

‘Hatchet job?’

‘Oh, don’t look so innocent, Ethelred. You knew that’s what Lucinda wanted. I told her – Ethelred has read all of Vane’s books, and loves them, but he will be quite happy to write the biography exactly as you wish. He’ll make Vane look a total prick, if that’s what you’d like. No extra charge.’

‘Is that why Bill Stanstead was stood down?’

Another writer had originally been commissioned to write the biography but had quit or been sacked, according to which version you wanted to believe. I was a last-minute replacement for him – Lucinda’s sixth or seventh choice, according to Elsie, and lucky to get the work on any terms. That was another reason why the project was running so late and I was chasing round trying to finish the research as quickly as I could.

‘There were reasons,’ said Elsie vaguely.

‘Why does Lucinda want a hatchet job, anyway?’

‘Don’t you listen to any of the literary gossip?’

‘Not really.’

‘Then you have some catching up to do. Are you sitting comfortably? Then I’ll begin. And please don’t interrupt until I’ve finished.’

‘I won’t,’ I said.

‘You just did,’ she said. ‘So, a long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away, Vane got Lucinda fired from her job as assistant editor at the big publisher she was then with. Vane wanted to move elsewhere and cited Lucinda’s failure to do something or other – missing a rogue semicolon during proofreading, or something equally serious – as his reason for quitting. He moved. She got the boot. Same day.’

‘That was a little unfair.’

‘I never said it wasn’t.’

‘But anyway she’s now a commissioning editor …’

‘Elsewhere. Yes, I know. But only for crap books like the one you’re writing. So, it’s not surprising she still hates his guts. She wanted the plain unvarnished truth – or plain unvarnished lies, if we could get away with it. Being dead he wouldn’t have been able to sue you or her or me or anyone else.’

‘Whereas now …’

‘Whereas now you’ve messed it up. According to your tweet, he’s alive and well.’

‘You never told me that,’ I said. ‘I mean that Lucinda wanted me to portray him as being in any way unpleasant. I thought I’d got the commission because Lucinda liked my work.’

‘Why would you think that?’

I sighed. ‘Well, I’ve always admired him – I mean his books – I’d never met him before today.’

‘I’m sure I did tell you, Ethelred.’

‘When?’

‘In an email.’

‘I don’t remember that.’

‘You remember all your emails?’

‘Yes.’

‘Then it must have gone astray. That’s probably why you didn’t get it. It happens. They go astray. Like dogs chasing rabbits. Anyway, the point is, Ethelred, that now he can sue us, so Lucinda’s not going to be pleased with you.’

‘He’s not alive just because I tweeted it.’

‘A lot of people won’t see it that way, Ethelred. Your presence on social media is pretty much a definition of whether you are alive or not. You have brought him back to life, a bit like that Frankenstein.’

There are plenty of times when it isn’t worth arguing with Elsie, not unless you are a great fan of logic being tested to destruction.

‘Fine. I’m to blame, then,’ I said, taking up my default position with Elsie. ‘At least I can just write the book I was always planning to write.’

‘Sadly, that is what you’ll have to do, unless the lawyers can find a way round it. Of course he was a shit. Always charming when he appeared on television or whatever, but not a nice man. If he didn’t like you, he’d make it clear he didn’t like you. If he hadn’t heard of you, he’d make it very clear he hadn’t heard of you.’ She looked at me and raised an eyebrow.

‘Possibly,’ I said.

‘And poor Tim won’t be pleased to see him back.’

‘No?’

‘Don’t you listen to any gossip at all?’

‘No, not even to the nice gossip.’

‘Ethelred, there’s no such thing as nice gossip. Not in publishing. What you may already know is that, pre-vanishing, Roger Vane and Tim were about to split up.’

‘Yes, I do know that,’ I said. ‘It was reported by some papers at the time. That’s why they thought Tim might have killed him. That and a rather confused account of what had happened on the day of Vane’s disappearance. Plus a scratch on his face. Plus getting out of Thailand before he could be questioned further.’

‘Indeed. All of those things. Circumstantial but damning nonetheless. The trip to Thailand was one last attempt to put it all right. But they quarrelled every evening. Loudly. In public. Other diners complained to the management. The hotel faced bankruptcy, having to refund people their restaurant bills. Travel agents noted an inexplicable drop in bookings to Thailand …’

‘Can you stick to something like the facts?’ I asked.

‘What? The real facts? OK, if that’s what you prefer. They had a very public falling out. Fact. Roger Vane disappeared. Fact. Tim returned to the hotel and ordered a gin sling. Fact. That, as you say, is why the Thai police thought Roger Norton Vane had been done in by Tim. Lovers’ tiff. Plenty of people here thought that too. But, and this is what you may not know, they also thought he’d been quite justified in doing so. If you’d asked anyone within ten miles of Fitzroy Square what they reckoned, they’d have replied: “The kid done ’im in right enough, but nobody round this manor’s going to grass ’im up to the Old Bill.”’

‘Are you imitating Vane’s substandard cockney dialogue by any chance?’

‘I thought I was imitating your substandard cockney dialogue, but I stand corrected as always. Anyway, most people did sympathise with Tim. I certainly did. I’ve told him so.’

‘He’s a friend, then?’

‘As it happens, I represent him. I signed him up a few weeks ago. He knows I’m always there for him if he needs me. He has merely to call.’

Elsie’s phone beeped. She held her hand up, as a polite instruction that I was not to interrupt whatever important thing was about to happen, and then checked the screen.

‘It’s Tim Macdonald,’ she said. ‘He wants a bed for the night. Roger Vane has thrown him out of the flat. That was quick work, even for him. Respect.’

CHAPTER FOUR

I had an appointment to see Cynthia Vane the following day. There seemed no reason not to keep it, just because the subject of my book was now more alive than we had suspected.

‘I looked out the photos you wanted,’ she said. ‘That’s Uncle Roger with my father, just before he vanished. That’s both brothers while they were still at school. Looks as if they’re on holiday somewhere. Norfolk maybe? Flat and sandy, anyway. I’ve also got one or two reviews of the earlier books that you may not have seen – my father must have cut them out and kept them. He was always very proud of Uncle Roger – even before they made the television series.’

‘It must have been a shock for you, yesterday. A very pleasant one, I assume, but a shock all the same.’

‘Pleasant? You think so? I’m not sure Uncle Roger was aiming for pleasant. But it was certainly a surprise for a lot of people. As you know, we’d already started the process of having him declared dead – legally, I mean. We’d accepted he was actually dead long ago. Except it turns out he was alive and living in Laos. Nice of him to keep us informed. It would have served him right if he’d shown up a couple months late and we’d given all his books to Oxfam. Some might call that harsh, but if you don’t contact your family for twenty years, it’s the sort of risk you take.’

‘So, what would have happened exactly, if he’d been declared dead – legally?’

‘Apart from Oxfam lucking out? His will would have been dusted off. Probate would have been obtained. Inheritance tax would have been paid. Distant and largely forgotten members of the family would have fought to the death over the ormolu clock. His gardening coat would finally have gone to a tip with facilities for dealing with hazardous waste. The flat would have been put on the market and been sold to some venture capitalist from Novgorod. His material existence would have been shattered into a thousand tiny fragments. I’ve no idea how you undo something like that.’

‘And who would have inherited the bulk of the estate once he was legally dead, if that isn’t an indelicate question? Tim, I suppose?’

‘Oh, no. Tim may have got something, but most of it came to me. That was one of the reasons why my father wanted to have Uncle Roger declared dead years ago – he’d long since given up any hope his brother was coming home and thought it was better the money and the flat were mine. But I’ve never felt inclined to push for it myself.’

‘The flat will have increased a bit in value in the meantime.’

‘I would imagine so. It’s all a bit theoretical now that he’s back. I’ve never done the sums anyway, so I’m honestly not sure how much money I’ve lost. Not that I wouldn’t always have preferred to have had Uncle Roger alive and well. If you’re planning to quote me in the biography, then just say his impoverished niece was delighted to see the rich, devious bastard back. As indeed I am.’

‘Tim couldn’t have been too keen on having Roger declared dead, though. He’d have lost his home. He’s lived there for twenty years.’

‘Well over twenty years. They’d been together for a while, in spite of frequent fallings out.’

‘He couldn’t have claimed anything as a right … if Roger hadn’t returned?’

‘I don’t think so. There was never anything formal – no civil partnership, for example. I’m not sure they had them then. The discovery that Uncle Roger was alive should have meant Tim could stay on – except Uncle Roger has thrown him out anyway. When you think about it, it’s not surprising he did – they were apparently about to split up when he disappeared. Tim’s had rent-free accommodation for twenty years longer than he might. And he’s got money. He can afford to buy somewhere of his own at long last. He can’t complain.’

There was a discernible note of contempt in her voice. But I had to agree – however things turned out, Tim couldn’t complain. As for her own financial loss, Cynthia seemed to be taking it well. She’d lost a flat but gained an uncle.

‘So,’ I said. ‘It’s all as if Roger had never gone away.’

Cynthia paused and looked at me. ‘Not quite. In some ways Uncle Roger is the same …’

‘But he’s altered in others? I have to say the years don’t seem to have softened him much.’

‘He’s lost none of his old venom, I’ll give him that. But he’s much greyer. And somehow smaller. I scarcely recognised him at first. It was only when the rest of the congregation started to exclaim it was him … Then you sort of saw it. The face. The posture. The way of walking. But sometimes you don’t immediately recognise somebody you’ve not seen for a few months if they’ve dyed their hair or lost a lot of weight. You can change a hell of a lot in twenty years.’

‘He probably had the same problem with the rest of you.’

‘That’s the odd thing – he didn’t. He recognised me straight away. Not even a hesitant “well, you must be little Cynthia”. I mean, I was in my early teens when he vanished. But he came right up to me and kissed me on the cheek. Not a moment’s doubt.’

‘There are photos of most of us on the Internet these days – Facebook, Twitter and all the new ones I’ve no plans to sign up to. It wouldn’t have been hard to find out what you looked like now.’

‘That’s true. There were other things, though, that he seemed to have inexplicably forgotten.’

Cynthia looked at me as if inviting the question. I obliged.

‘Such as?’ I asked.

‘Oh, he and my father had a terrier called Bramble when they were younger, but when I mentioned Bramble he just looked completely blank. Then, claiming to recall the animal after all, he referred to Bramble as “he”, when he would have known she was a bitch. You don’t forget things like that. It would be like thinking you had a son when you had a daughter.’

‘A slip of the tongue.’

‘I suppose it could be. It’s easily done. You think of dogs as “he” don’t you? And cats as “she”. But even then …’

‘Do you mean you think it isn’t him?’

‘It looks pretty much like him, and certainly sounds like him … I’d like it to be him. Really I would. Uncle Roger is the only close member of family I have left, apart from my mother. But even so … What do you think, Ethelred?’

‘I never really knew him before,’ I said. ‘Certainly not like you did. But I saw him plenty of times on television and once or twice on the stage. There’s nothing to make me think he’s an imposter.’

It was, I had to admit, not the most ringing of endorsements. But surely nobody would attempt to impersonate a figure as famous as Vane – especially when there were two close members of his family still around?

‘He knew who cousin Wilbert was,’ said Cynthia thoughtfully.

‘There you are, then. I haven’t come across Wilbert. Distant relation?’

‘Non-existent relation. Possibly on my father’s side. I made him up on the spur of the moment. “Cousin Wilbert will be pleased to see you again,” I said. “I’ve always liked Wilbert,” he replied.’

‘So he failed the Wilbert test?’

‘I’d say so, wouldn’t you?’

‘Maybe he misheard?’

‘That’s charitable of you, Ethelred. Your good nature shines through in a generally shitty world. But no, I don’t think there’s anything wrong with his hearing. It’s more to do with the fact that … how can I put this? … I think there’s just a chance he’s a total fake.’

‘Really?’

‘Don’t look at me like that. The money has nothing to do with it at all. Except that I wouldn’t want Uncle Roger’s money going to a gold-plated shyster. Whatever’s going on, I’m going to get to the bottom of it. Then quite possibly I’m going to kick some ass.’

‘Good for you.’

‘Yes, that was what I thought too. I have a plan, Ethelred. There are still plenty of people around who will remember him well. I won’t be the only one with doubts.’

‘Probably not. I’ll need to write a slightly different book, of course, if he is an imposter.’

‘Not really. Just a different postscript. Don’t worry, I’ll keep you informed. He may still prove to be a genuine uncle with a poor recollection of dogs. What can I do for you in the meantime?’

‘Just one or two queries about his time at university,’ I said. ‘Then I’d like you to run over the last time you saw him – before the memorial service, that is.’

‘OK, try me,’ she said.

It was an hour or so later that she suggested a break for coffee. She switched on the television because Roger Norton Vane’s reappearance was still news. The previous evening, crime writers had queued up to say how delighted they were that he was still alive. Bookshop owners were interviewed, saying that their shelves had been stripped of anything by Vane or by anyone remotely resembling him. It was likely there would be more of the same this afternoon, though perhaps only as a brief final item. In fact he was second on, after something on the US presidential election.

The announcer switched from the bemused smile appropriate to the previous item to a disapproving frown and said: ‘And now over to our arts editor for some surprising developments in the Roger Norton Vane affair.’