8,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

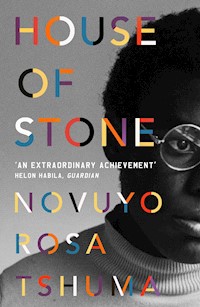

Winner of the Edward Stanford Prize for Fiction with a Sense of Place, 2019 Shortlisted for the Dylan Thomas Prize, 2019 Shortlisted for the Orwell Prize, 2019 Longlisted for the Rathbones Folio Prize, 2019 __________ 'Extraordinary' Guardian __________ Bukhosi has gone missing. His father, Abed, and his mother, Agnes, cling to the hope that he has run away, rather than been murdered by government thugs. Only the lodger seems to have any idea... Zamani has lived in the spare room for years now. Quiet, polite, well-read and well-heeled, he's almost part of the family - but almost isn't quite good enough for Zamani. Cajoling, coaxing and coercing Abed and Agnes into revealing their sometimes tender, often brutal life stories, Zamani aims to steep himself in borrowed family history, so that he can fully inherit and inhabit its uncertain future.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

HOUSE of STONE

HOUSE of STONE

Novuyo Rosa Tshuma

First published in hardback and trade paperback in Great Britain in 2018 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Novuyo Rosa Tshuma, 2018

The moral right of Novuyo Rosa Tshuma to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

Excerpts from THE WRETCHED OF THE EARTH by Frantz Fanon, English translation copyright © 1963 by Présence Africaine. Used by permission of Grove/Atlantic, Inc. Any third party use of this material, outside of this publication, is prohibited.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 78649 316 3Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 78649 362 0EBook ISBN: 978 1 78649 317 0

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic BooksAn imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House26–27 Boswell StreetLondon WC1N 3JZ

For T. D.

CONTENTS

Prologue

BOOK ONE

Of Fathers and Grandfathers

Thandi

A Budding Romance

The Mbira

Spear-the-Blood

Fathers

‡khoā

A New Country

The Men in the Red Berets

Uncle Fani

Black Jesus

BOOK TWO

An Arranged Marriage

The Prayer Meeting

Fire on the Mountain

The Outing

The Box

April Baby

The Commission of Inquiry

Bhalagwe

The Invasion

The Reverend Pastor

BOOK THREE

Uncle Fani’s House

Help Me

Forbidden Fruits

Black Jesus

Christmas Day

Acknowledgements

Prologue

Iam a man on a mission. A vocation, call it, to remake the past, and a wish to fashion all that has been into being and becoming. It all started when my surrogate father, Abednego Mlambo, sought me out in my lodgings two days ago with a bottle of Bell’s in one hand and two crystal glasses pressed to his chest. He was dressed in a pair of his faded, beige don’t-touch-my-ankles trousers that give him the look of a civil servant, complete with a matching shirt.

He held the crystal glasses in place with his chin, one balanced atop the other, the bottom glass clasped between the thumb and forefinger of the hand clutching the Bell’s, the top glass muzzling his mouth, so that his voice reached me as though a daydream, as he said, raising his free hand and slapping my back, that he appreciated how I had taken his son Bukhosi under my wing, playing big brother, and that I was like a son to him and he would, from then on, call me his surrogate son.

It would have been perfect, and may even have made me cry, for no man ever claimed me as his son, had Abednego not beaten me to it, his sagging yellow face suddenly mugged by sadness as he began to shed tears for that Bukhosi, like he has been doing ever since the boy went missing. If only he knew how the boy once made the eerie confession that he wished it was I who was his father and not he, Abednego, never mind that I’m only twenty-four and Bukhosi had just turned seventeen.

He’s been missing for over a week, since the beginning of October. Yes, I must say it again to believe it, it’s already beginning to feel to me as though the boy never existed at all: Bukhosi is missing. BUKHOSI IS MISSING. Bukhosi is missing. Abednego sat down heavily on my little put-me-up bed, still clutching the whisky and the glasses, and snottily apologized for crying. I watched his tears drip-dripping into the crystal glass, like our taps on the days when the municipal doesn’t cut off the water supply, and tried to cluck sympathetically. He confessed that it pained him to say the boy’s name out loud, to look up as though at any moment he would hear his heavy steps thudding on Mama Agnes’s polished cement floor and see his plump, walnut face peeping around the living room door.

I wanted to reach out and hold him, but we had never shared such moments, him and I. I had seen him lean into Mama Agnes’s embraces, inhaling the scent of her perfumed bosom as she hugged him in greeting when he arrived home from those long hours at the Butnam Rubber Factory. I had also caught him and Bukhosi once, locked in an uncomfortable grip, something almost like a hug, but not quite, for their faces were held apart even as they squeezed each other’s shoulders.

‘We’ll find him,’ I said, relieving him of the glasses but not the whisky, which he clutched possessively. ‘I’m here for you.’

‘Bukhosi,’ he muttered again, wincing as he said it, speaking it out loud in the same way God bespake Adam into existence, croaking Bukhosi and therefore he was; except he wasn’t. And me, I winced because I suspected he may never be found, for I was there with him when he disappeared – we were chanting side by side at the rally held by the Mthwakazi Secessionist Movement only nine days ago, on Sunday 7 October, in Stanley Square. The flame-lilies were raging, the sunflowers sashaying and our secessionist leader Dumo spraying us with his saliva as he frothed up a call to arms, to secession, to revolution, to freedom!

‘Secede from the country Zimbabwe,’ he cried. ‘Secede!’

‘Secede!’ echoed our fevered chorus.

‘For our brothers killed in the ’80s in the Gukurahundi Genocide!’ he cried. ‘Secede!’

‘Secede!’ we echoed.

‘Secede from tyranny!’

‘Secede!’

While we were thrusting peaceful fists of revolt in the air, the riot police thrust themselves on our gathering, gathering those of us who could not run fast enough into the backs of their police vans. And that was the last time I saw Bukhosi and that’s when he went missing.

What would Dumo say to me now? Speak Truth to Death or Live a Dead Lie! I never understood half of what Dumo said, but he had an uncanny knack of somehow hitting your heart, regardless. Dumo, who tried to be my mentor and, more importantly, nursed my grief after my Uncle Fani’s death, a grief that turned me delirious for a time; Dumo who, even so, never tired of lambasting me, telling me I was useless as a revolutionary protégé, lacking the kind of recklessness necessary to resurrect insurrection.

But what does it matter what he would say to me now? I’m the one who’s survived and he’s the one who’s disappeared, thanks to those mad man antics of his. Poof! Like a spoko. He too was gobbled up by one of those police vans the day of the Mthwakazi rally, and has not been regurgitated since.

Like Bukhosi, I doubt I’ll ever see Dumo again. It was he who taught me that a man could remake himself by remaking his past. So, when Abednego said I was like a son to him and that he would, from then on, call me his surrogate son, I felt a swell of pride and the prick of opportunity. Perhaps, as my surrogate father’s son, I can be blessed with some familial affection and, in this way, finally powder away the horrors of my own murky hi-story bequeathed to me by parents I never knew.

I have begun calling him, jokingly but in all seriousness, surrogate father. And let this surrogacy business fool no one, I intend to be as close to the Mlambos as any real son would be, bound, happily, by the Bantu philosophy of ubuntu, that communal pedigree. And even though I’m just a lodger in the pygmy room they have squeezed into their backyard so as to rent out in these trying times, only the narrow corridor of a dirt path separates me from their back door; even though I’m just their lodger, we already have a shared history, the Mlambos and I, for though they don’t know it, I grew up in this house, it belonged to my dearly departed Uncle Fani.

Perhaps, despite his incessant worrying over Bukhosi, Abednego really is beginning to think of me, too, as his son. Why else did he then wipe his eyes, set his shoulders and proceed to pour us both generous portions of Bell’s in the crystal glasses? And why, in spite of the fact that I knew that he’s a recovering alcoholic who’s been sober for five years straight, since 2002, and even has a five year AA Bronze Medallion to prove it, did I indulge him and drink the Bell’s? Perhaps it was because of my eagerness to consolidate this new claim to sonhood. He quaffed his Bell’s much faster than I mine, topping himself up often and liberally, until he was drunk blind and chatty proper, and then began chittering at length about his past. I did, then, what I understood he was asking me to do; I began to chronicle the family hi-story he was entrusting me with, like any good son would.

Our conversations, which started two days ago, are more in the way of one-sided confessions and always in the pleasant company of whisky – which I’ve started supplying since, without it, my surrogate father is rendered a grumpy mute – and take place in between our community searches for Bukhosi. We sit more often than not in Mama Agnes’s living room, just he and I, he slumped in his sofa, I administering the Bell’s. It takes him a while to get to the meat of the matter – he does have a tendency to go on and on about the boy. Mama Agnes, thankfully, is always away during the day and, sadly, late into the night, these days, either at work on the other side of town in the leafy Suburbs at Grahams Girls’ High where she teaches English, or at her church Blessed Anointings where she goes every day to beg, bully and bootlick the Holy Ghost into revealing the whereabouts of her Bukhosi, so far to no avail. My surrogate father has given himself indefinite leave from his work at the Butnam Rubber Factory, until his son is found, he says.

These intimacies that my surrogate father has begun sharing with me are what Bukhosi always wanted from him. The boy badgered our father about the family hi-story. ‘Baba,’ he would ask, at first timidly, for he anticipated the rage such questions caused Abednego, who was never stingy with the belt. ‘Baba,’ although not even the prospect of the belt deterred him. ‘I want to know, Baba,’ so strong was this desire, so brilliantly did it flicker in his emerald eyes. ‘How did you grow up … ?’ Shimmering like a thing hungry and searing and lost. ‘Where were you during … what was …’ Growing ever more defiant after I introduced him to Dumo, who took him under his wing, like he had tried to do for me, feeding the boy’s hunger to know the past. ‘I need to know, you have to tell me …’ His seventeen-year-old voice booming with a dangerous bass, suddenly mature in its insolence, different from his usual brattishness. ‘I demand to know what happened during Gukurahundi!’

What anguish this caused our father! I noticed how his hands trembled, how it wasn’t anger that made his mouth froth and sputter but something more substantial, making the sweat break out across his forehead. And though he beat the boy, it wasn’t really the boy he wanted to beat, but, it seemed to me, himself…

The boy didn’t know when and how to push, didn’t know how to cultivate the kind of rapport a son needs to have with his father. But I’ve been watching, I’ve been paying attention, and I know how to be around a man when he’s down. There’s a certain silence that’s soothing, and the way to do it, I’ve discovered, is to act as though what has just happened, the flimsy beating and ineffectual yelling and the tremors, is nothing. To change neither tone nor body language. And I did this well; if I was reading the paper when a beating happened, I would continue to read the paper. I only sort of interfered when Mama Agnes was home, for she would rush to the scene, yelling for Abednego to stoppit as she tried to leap between him and the boy. Here, I would jump up and dither behind them, as though I were doing something useful. And afterwards, I would make Mama Agnes a cup of Tanganda tea, steeped for five minutes in boiling water, with a dash of lemon, just the way she likes it.

The only thing I ever ventured to say to Abednego, just once after one of his altercations with the boy, was, ‘Were I your son, I would never speak to you like that.’ I made sure not to look at him as I said this, to keep my eyes glued to the TV, which I had been watching when the whole thing happened, so that it was as if what I was saying was really nothing. And right afterwards, I turned up the volume and laughed along to whatever show was on, though I don’t remember much about it now, I wasn’t paying attention. I could feel Abednego’s eyes on me, and my heart was loud in my chest. I feared I had pushed too hard, that I shouldn’t have said anything, and that by speaking about it, I had angered him where I meant to soothe. But he didn’t rebuke me; he didn’t say a thing. Instead, that evening, after the electricity had abruptly cut out, as it usually does nowadays, he invited me to sit with him around the fire in the backyard, where Mama Agnes was making supper, and play a game of draughts.

To hear him call me ‘son’, even if ‘surrogate son’, when he sought me out two days ago in my lodgings, was the sweet fruit of a long labour. But never would I have thought my surrogate father would not only call me ‘son’, but bring me into the intimacies a father shares with his son – the family hi-story. Perhaps, had my surrogate brother Bukhosi understood our father and known how to talk to him, he, too, would have been brought into the intimacies of our family hi-story, and gained the solid footing he so desperately needed, but because of the lack of which he became lost, and because of the possession of which I am now found. Lost and found! Lost and found.

BOOK ONE

Of Fathers and Grandfathers

A man of consciousness, gifted with a mind and a blank screen and a keyboard such as I have, makes his own hi-story proper. There is no better way of gaining possession of yourself than chewing the bones of the mind over the question, Who am I? And who you are starts with a robust family lineage in which to cultivate your roots. A man has to be able to trace the details of his family hi-story at least two lineages down, to his grandfather. Otherwise, he can’t really claim to be standing on solid ground. You have to be able to point to a man and say, ‘That’s my grandfather.’ Or make do with a sepia-tinted photo, at least, chewed at the edges by the affectionate teeth of time.

As my surrogate father has neither glossy photo nor the confidence to point and say, ‘That’s my grandfather,’ I have been left with the task of resolving the matter of our family lineage. And it hasn’t been easy, this. For, one moment, while ensconced in the toasty Bell’s, Abednego claims that his father was the man he grew up calling ‘Baba’, husband to my surrogate grandma, that treacherously demure woman who was in her heyday such a blot-out-sun, so blinding was her beauty. And then, the next moment, having become much too heated from the Scotch whisky, he makes rather dubious assertions that his real father is a certain James Thornton, once-upon-a-time owner of that Thornton Farm whose lush harvests salivated many a tongue in the adjoining Tribal Trust Lands where young Abednego grew up, relegated to live there by the state during the time of racial segregation, back when Zimbabwe was still Rhodesia.

When he blubbered this in my lodgings two days ago, I wrinkled my nose and raised an eyebrow. Frowning, he pulled up his shirt sleeve and thrust his arm in my face, prodding the flesh. His inner forearm, which doesn’t get much sun, is closer to cream than yellow, and the hairs are a pale gold rather than a deep brown.

As though sensing still my scepticism, he launched into a dramatic monologue of the day the farmer attempted to lay claim to what, by blood and sperm, was allegedly his. Baba was sitting outside his hut in the shade of the mopane tree on the morning in question, cleaning his FAL rifle and decked in his full Rhodesian African Rifles army apparel – a bush-green shirt tucked into pleated shorts, woollen hose tops, black stick boots and a slouch hat – busy bobbing his head solemnly to my (surrogate) Uncle Zacchaeus as he read verses from the bible, in an English that the old man understood and extolled but did not himself know how to read, when Farmer Thornton came wheezing over the hill of the north-east, from the direction of his farm, telephone cord in trembling hand, dust simmering about his sandalled feet. My surrogate father Abednego, who had been crouching behind the kraals some hundred paces from the mopane tree, listening to Zacchaeus read and trying rather unsuccessfully to mimic his brother’s fanciful pronunciations, straightened up and gawked at the farmer.

‘Give me the boy!’ cried Farmer Thornton, gesticulating towards Abednego and lambasting Baba for not looking after him right, for sending the little munt Zacchaeus to school and not my surrogate father.

My surrogate father began to squirm, his yellow face ripening at the farmer’s outburst. He’d never thought, in all his nineteen years, that he could go to school. Zacchaeus was the special one, the younger son and yet the cimbi of Baba’s heart, and although something bilic used to brew inside him during those first days when he would watch his younger brother being shaken awake every morning to go to the sole school for Africans in the district some thirteen kilometres away, this bile had since settled in its rightful place in his gallbladder.

The farmer’s outburst made him feel all funny inside. He knew and had always taken secret delight in the fact that the farmer had always had a thing for him. Everybody knew, Baba, mama and even Zacchaeus whose buttocks the farmer always thrashed with a telephone cord whenever he caught them stealing crops in his fields. But this impassioned outburst, now, that was another thing altogether, bound to find the ears of the wind and be carried for an entire jealous village to hear. And so he squirmed, my surrogate father, and scowled and made all sorts of ugly faces, all the while secretly savouring the farmer’s words.

Baba raised his rifle until it was trained on Farmer Thornton. ‘Get away from here, mani, you fucking civvy!’

‘You dare to shoot me? You dare to shoot me, you munt, you dare to shoot a Rhodie?’

‘A Rhodie? You want to prattle to me about being a Rhodie? I was a Second Lieutenant in the Royal Rhodesian African Rifles, dammit, I served under Colonel J. F. Clayton and His Majesty Colonel-in-Chief King George VI, I fought alongside your superiors in Burma, the well-tempered Brits, bless their hearts, I killed men worthier of life than you, you Rhodie, and I will shoot you right here right now for nuisance behaviour in the presence of army personnel!’

Out of the corner of his eye, to his right, my surrogate father caught sight of his mama thrusting her head out of the kitchen hut, and then, upon seeing Baba and Farmer Thornton and the gun, she snatched it back in.

‘Step back, civilian! I’m warning you!’ yelled Baba.

‘Just give me the boy!’

Baba spat and cocked his rifle.

Off ran Farmer Thornton, back to his farm that flanked the Tribal Trust Lands, his red dungarees stopping just short of his ankles, making him look like a ragamuffin fleeing the scene of a crime.

Later that night in my pygmy room, I clickety-clacked on my MacBook and Googled this James Thornton. I found his blog, RHODESIANS NEVER DIE, which, along with a host of memories, patriotic ballads and tchotchkes of days gone by, plus the key words ‘Rhodesia’, ‘Prime Minister Ian Smith’, ‘platoon’, ‘munts’, ‘gooks’, ‘G. A. Henry’ and ‘terrs’, sports sixteen thousand email subscribers and an average of fifty thousand unique visitors each month.

I was surprised to see that my surrogate father and the farmer share a distinctive pair of wide, flared nostrils shaped like inverted teardrops, which seems to rather settle the question of fatherhood, even though immediately after recounting the Battle of the Fathers, Abednego had suddenly and vehemently declared to me that he was no son of a settler, that the old farmer was senile, that he had received his yellow skin from his mama’s side, passed down through the genes by an Indo-Caucasian great-great-great-great-grandma.

He’s going to have to come to terms with it all, sooner or later. Patrilineage is, after all, the well from which a man’s identity springs; we are our fathers’ sons, inheriting traits, mannerisms, talents and penchants. What delight to know your roots! To be firmly rooted. To look into a face and see in it something of your own. To notice a familiar tic. To come into knowing of your father’s fathers and their fathers before them.

What would his life have been like had he known, from the very beginning, his true ancestry? I wonder what my life would have been like, had I grown up knowing my father. There are terrible rumours, but no, this man who my Uncle Fani named, five years ago on his deathbed, has so much darkness in him, and me, haven’t I always leaned towards radiance? Besides, he was delirious, Uncle Fani; who is to trust the piffle of a dying man? But what would it have been like, to grow up knowing my forebears? What would it have been like for my surrogate father, had he grown up knowing his forebears? Would he have grown up roaming not the gecko-studded mud huts of his Baba’s compound but the dapperwood halls of that two-storey Thornton Farmhouse, his yellow skin made prickly by the disapproving glares from the framed photographs of his forefathers – the farmer’s temerarious grandpapa William Thornton Senior, slayer of natives and founding father of the Colony of Southern Rhodesia, and his equally valiant papa Captain William Thornton Junior, slayer of both natives and Germans in World War One under the flag of His then Majesty King George V – God Save the King!

These lives of our ancestors are chronicled on Farmer Thornton’s blog, which, given the farmer’s declared ambitions of attracting a large enough following to turn his Life and Times into a TV series, offers an embarrassingly uncensored hi-story of our patrilineage, the Thorntons.

This blood and sperm business started when the farmer lost his young Sonny Boy, killed in March of ’74 when those bantu terrorists puppeteered by World Communist Elements ambushed his regiment’s truck near the Rhodesian army camp at Fort Hare – the farmer’s words as per his blog, not mine! He was twenty-two and the only heir to the Thornton dynasty. Or maybe not. Though there aren’t outright confessions of Abednego as the bastard son from the farmer on his blog, I did find, amidst raunchy recollections of gyrating to the rhythm of cocoa-coloured hips in his younger days, a hangdog confession of ‘an ebony belle whose tsako made his heart lollop’. Can it just be coincidence that the pictures I’ve seen of my surrogate grandmother show a woman whose broad grin is split with a perfect gap between her two front teeth?

Said belle was the cause of his fall-out with his Ennis (Mrs Thornton) who threatened to leave him, foul-mouthed with fury, using words she never used, like Fassyhole and Quashie, until the farmer asked her if she’d been hanging around a Mrs Willoughby again. Ennis’s threats must have won the day, because there is little much else said about this ebony belle in the pages of his blog. Instead, these amorous accounts give way to the farmer’s rants against Her Majesty’s government for betraying his beloved Rhodesia.

These rants are very lengthy, at times talking about Rhodesia as though the past were present, cursing the ‘Mother Country and her cronies for selling the whites down the river’, at other times devolving into fantasies of a twenty-first-century Rhodesia that has been reinstated to its former glory … ‘Make Rhodesia Great Again!’ These diatribes bring him a surprising number of views for each of his posts, but none so much as the one that went viral about how he found his Ennis lying on the floor one day in the ’80s, during the time of the Gukurahundi Genocide, having been raped and strangled by the dissidents. I cried when I read about Mrs Thornton’s brutal murder. She would have been my step-grandma, my surrogate-surrogate grandma. Reading the farmer’s reminiscences, I felt that I’d lost my very own flesh and blood – my very own grandma!

Yesterday, Abednego asked me, for the umpteenth time, where it is I think ‘he’ could have gone.

I could feel something hot and crusty rising in my chest. ‘Who?’

His shoulders fell. ‘No, wena. Don’t do that. You know who.’

I leaned over and tipped the bottle of Bell’s into his glass. I needed him to stay focused. I wanted to find out what happened after Farmer Thornton had tried to claim him as his son. ‘You were telling me about being sent to Bulawayo, after your Baba sent the farmer packing?’

He just sat there, blinking at the damn glass. ‘I was going to take him to watch soccer that Sunday, you know. Highlanders was playing at Barbourfields Stadium. I had thought … He was behaving strangely, did you notice?’

‘What was it that made Baba suddenly decide to send you and not Zacchaeus to—’

‘The other day, he raised his voice to his mother. It was like a fist, the force of it, and I saw how she flinched—’

‘—why did Baba send you to Bulawayo?’

‘Maybe he spoke to you, did he tell you anything? About where he was going?’

I sighed.

‘Did he tell you anything?’

‘He didn’t.’

‘You don’t have even one idea, nje, where he might have gone?’

‘… hmm hmm.’

‘What?’

‘I said, I have no idea where he went.’

‘But you’ll come with me tomorrow morning to look, isn’t it?’

‘OK.’

‘He liked you … Likes. He likes you … I always tried to be a good father. He knew that, didn’t he? Knows. He knows.’

How creased his yellow face became! It flitted between an inward, mustard despair and a jaundiced hope that radiated outward, towards me, enveloping me, filling the room, filtering between the burglar bars of the living room windows and out into the Monday afternoon. I was suddenly overwhelmed by the urge to lean over and squeeze his arm. Instead, I fisted my hands and tucked them beneath my armpits. ‘Yes, of course, he knew you loved him.’ I could have told him what the boy had really thought of him; but is there a point in crushing a man with the truth? ‘He always told me how he loved you.’

A light glinted in his eyes.

‘Don’t worry!’ I said. ‘We’ll find him!’

He seemed to consider this. ‘You think so?’

‘Certain hundred per cent!’

I am, of course, certain of nothing. But what does it hurt to give a man a little hope? He is, like me, floating, my surrogate father. He, like me, never managed to get close to his Baba. Like him and Bukhosi, him and his Baba had a rather tenuous relationship. He and Uncle Zacchaeus were born after their Baba’s abrupt return from his service in the Second World War, where he had fought on behalf of the Mother Country under the Rhodesian African Rifles, serving for four and a half years. For four and a half years, Abednego’s mama was a fresh, young, supple bride without her husband to cultivate her. No wonder she and that Farmer Thornton … And then, he returned to her an old-young man, my surrogate-surrogate grandfather, with voices in his head. This version of the old man, with his voices, is all my surrogate father knew of him, although he remembers his mama relating wistfully another Baba only she had known, a charming young man with wild ambitions of one day acquiring enough education to become someone important, like a teacher or even a lawyer, forced by the times to work as a labourer in the Tsholotsho Mines, a job that began to kill his dreams piece by piece … And then, like most young men at the time, he had, taken over by the querulous passions of youth, run off after the romance of war, that unbearably seductive mistress who promises the kind of ecstasy young men dream of in their sleep, wetting them with excitement.

His discharge papers, according to Uncle Zacchaeus, who’d started snooping around the souvenirs decorating the old man’s hut ever since he’d learned how to read, said, Reason for Discharge: Severe Stress Response Syndrome. Recommendation: No longer fit for service.

Abednego was nineteen when his Baba sent him off to Bulawayo, in April ’74, just a month after the death of Farmer Thornton’s Sonny Boy and, I’m guessing, about the same time that the farmer would have visited the Mlambo homestead.

I tried one more time to get him to speak. ‘Come on. Let’s talk about other things. Tell me, why did Baba send you to the city?’ I already knew, of course. I can imagine how angry Baba would have been when Farmer Thornton marched in demanding his progeny back. It’s easy to pretend that some things aren’t true until some loudmouth speaks them into being and makes them concrete. And once out of the mouth, a secret cannot be taken back. It hovers in the air and becomes pregnant from all that potent silence, birthing, inevitably, a new course for a life.

Abednego turned the tumbler of whisky and then drained it. As if the alcohol oiled his voicebox, he settled back into his chair, and finally resumed his story.

‘Atte-nnn-tion!’

He had been summoned to the old man’s hut. He raised his hand in a reflexive salute.

‘Right, soldier, get on the floor and give me fifty!’

‘Sir, yessir!’ he said, and lowered himself to the dung-and-mud floor, where he began to huff and puff out fifty press-ups. Baba began pacing the length of the hut, his boots making muffled thumps that Abednego could feel vibrating through his palms.

‘The enemy is upon us, soldier,’ Abednego heard him say, his voice rising and falling with his pacing. ‘I’d say we attack, but a tactical retreat would be the wiser thing to do, for now.’

‘Whatever you think is best, sir!’

‘Don’t interrupt your Lieutenant, soldier, I’m doing some thinking.’

‘Sorrysir!’

‘I’d say we withdraw further south. Tsholotsho’s probably too close, and too small, hardly a hamlet, they’ll find us there. Hmmm, what to do …’

‘… twenty-two, twenty-three, twenty-four …’

‘… I’d say Bulawayo’s the place.’

Abednego stumbled and flopped. ‘Did you say Bulawayo, Baba?’

He could scarcely believe what Baba seemed to be saying – he, and not Zacchaeus, was going to experience big-city living! Zacchaeus whose eye, at sixteen, had already taken on the sheen of arrogance as it cast itself across the rocky, scraggly Tribal Trust Lands to see not sand and scrub but faraway places, big-city living in Bulawayo.

‘I shall forage towns and cities, brother, and even whole countries, for worldly wisdom,’ his younger brother had taken to declaring of late during such moments of haughty-eye-roving. ‘I shall fashion myself into a Great Colonizer, a Cecil John Rhodes, a David Livingstone, a Christopher Columbus. I’m destined for great things! Everyone sees it in me. Say, what do they say about you, brother?’

And so there he was, my surrogate father, having been in the city of Bulawayo for four days, failing still to name one auspicious thing anyone in his village had ever said about him. He was standing outside the Rhodesia Railway Station, carrying an application for the position of train driver, which he’d happened upon in the classifieds of the Bantu Terrorists: Rhodesia’s Communist Threat newspaper sheet he had in hand, ogling the station’s red-brick facade and its tusk-coloured entablatures, and squinting horribly, so as to better see, through the mist of his humble roving eye, the blurry visions of the towns cities and countries he intended to forage, and the foggy self-fashioning into a Great Colonizer a Cecil John Rhodes a David Livingstone a Christopher Columbus, when he saw, flickering past, neither flash nor vision, but Thandi, a distraction he would otherwise have ignored were it not for the fact that his manhood reared to attention, like a flag suddenly thrust at full mast.

‘Thandi?’ I asked, desperately intrigued.

‘Shut up, mani, I’m talking,’ he barked back.

Thandi. She was walking down Customs Avenue, glistering umber limbs swaying one-two one-two, as though to a song, breasts bounce-bouncing and buttocks jounce-jouncing to the same tempo.

All at once, the railway was forgotten; the city could be foraged for wisdom another day; said manhood was busy conducting public misdemeanor; and before he knew what he was doing, he was following her.

Thandi

It felt good to accompany Abednego and the neighbourhood committee in search of the boy today. Honestly, I didn’t want to go, but the way Abednego warmed up to me after I offered to print out posters of Bukhosi’s blunt face to plaster all over our Luveve Township made it all worth it. He slapped me on my back, and said, ‘Yebo yes, boy!’ His hand lingered there, warm and solid, and I leaned into him slightly; I could smell Bukhosi’s Lifebuoy soap on him.

After the community search, which consisted of going door to door asking after the boy, and pasting up his posters, my surrogate father invited me to share a beer with him at the shebeen. My heart lolloped at the thought that it would be just us two, but then he also invited the other men from the township who had accompanied us on our search. And though I sat next to him, and tried to laugh louder than the other men at his jokes, which weren’t all that funny, he didn’t once look my way. It was as if I wasn’t there. I can’t stand him when he gets like that. Eventually, I slipped away, and took a khombi into town; I just couldn’t stand feeling as though I was back to just being his lodger again.

I found myself retracing the steps across the city my surrogate father took when he followed the young woman, Thandi, from the railway station all those years ago.

Yes, he followed her. What else could he do but follow her?

(I felt strange, having to look up the old, colonial names of the streets back in Thandi’s time when Zimbabwe was still Rhodesia. It was like I had been transported to another Bulawayo on another Earth in another multiverse. I found myself pussyfooting on those colonial streets of the past, as I’m sure my surrogate father had, too.)

She hurried down Customs Avenue, took a left onto Prospect then another quick left onto Jameson; a right onto Fourteenth Avenue; crossing the wide thoroughfares with incredible speed, past Fort, past Main, continuing across Abercorn, across Fife, across Rhodes; and then a left onto Grey Street, where she slowed down and walked with her hands tucked in the front pockets of her sapphire frock, straining her neck as she ambled past the Royal Cinema to glimpse the white teenagers standing in line.

She crossed the street and entered Downing’s Bakery, redolent with the aroma of freshly baked bread, which my surrogate father could smell all the way out on the pavement where he stood looking sheepish waiting for her to emerge, too afraid to follow her in. She appeared a few minutes later with a steaming chicken pie and a Fanta, which made his stomach rumble, and turned left onto Selbourne Avenue, moving at a leisurely pace, munching on her pie and pausing every so often to tilt the Fanta to her lips. Down Selbourne she sauntered, across Rhodes Street he followed her, where he paused, gaping at the off-white building of the Bulawayo City Hall with its Tuscan columns and the tower clock chiming every quarter hour. She crossed Fife Street and was now strolling across Abercorn, then Main, where all of a sudden he dropped to the ground, startled before the Gatling Gun, which stood threatening him outside Asbestos House, its muzzle trained on him and Selbourne Avenue behind. But the gun was just a monumental relic, rusty and out of use, without a gun master. Embarrassed, looking furtively about to make sure no one had seen him, he stumbled after her, on Selbourne Avenue still, across Fort and then Jameson, and then a right onto Lobengula Street. Here the crowds became darker of skin and also more compact, the thoroughfare still impressively wide. Her shapely rump beckoned him, flitting seductively in and out of the throngs, until she swung quite suddenly into Ticki-Tai Convenience Store at the corner of Lobengula and Third Avenue.

Ticki-Tai Convenience Store, where the young woman Thandi worked, on Lobengula Street, is now a phone-and-internet shop. I stood on the pavement staring at it for a long time, much in the same way my surrogate father said he stood waiting for Thandi in April ’74. I even leaned against the broken parking meter outside the phone-and-internet shop, much like he said he had leaned against a parking meter all those years ago outside Ticki-Tai, in a pose of affected nonchalance. There he remained, sweating in an afternoon sun that seared the Bulawayo skyline, until the shadows began to spread across the pavement and cast a soothing shade where he stood. When his legs began to burn and still Thandi had not appeared, he shuffled back to the entrance, counted one, two, three, and ducked inside.

The interior was stuffy, suffused with the sweet scent of strange spices and the earthy smell of chickenfeed, with one aisle leading from the entrance along which he had to sidle, his chest rubbing against sacks of produce, and also television sets, radios, gramophones, bags of mealie-meal and sugar, piping, taps, sinks and steel rods.

‘Hello? Yes? May I help you?’ she said in English. Her voice was tantalizing, like a glob of honey on the tongue.

She was sitting on a high stool behind the counter. A book was perched on her lap, dipping into the col between her thighs.

‘Eh … halloo,’ he said. He found he could not look her in the eye.

‘Yes? How can I help you? Are you looking for anything in particular?’

‘Actually, ehm …’ He rubbed his palms on the back of his trousers. ‘It is you I am looking for.’

Her face shadowed. ‘What do you want?’ And then, her eyes falling on the Bantu Terrorists: Rhodesia’s Communist Threat newspaper sheet that he still clutched in his hand: ‘Who sent you?’

He was both taken aback and thrilled by the directness of her manner. No shy giggling, flits of the lids or shrug of the shoulders like the girls in his village.

‘Ahem … let me, let me introduce myself. I am Abednego Mlambo, the Mlambos of Lupane, near St Luke’s Mission Hospital, do you know where it is? I, I saw you walking and ehm … you are so beautiful …’

She threw back her head and laughed, bringing into profile the striking length and curve of her neck. Her breasts jiggled beneath her exquisite little collarbone. He wondered if they were soft and mushy like the inside of an over-ripe pawpaw, or lumpy like the inside of a granadilla.

He smiled and scratched the back of his head.

‘I love you,’ he said finally.

Laughing still, she shook her head.

‘But I do!’

‘Th-andi? Vat is it? Remember, you is at vork. No visitors during vork hours.’

He turned around, to find a large Indian woman in a silver lehenga standing by the ‘staff only’ entrance at the back, frowning not at her, but at him. She pronounced the ‘Tha’ part of her name as the English ‘Th-a’, with her tongue between her teeth, instead of the soft Ndebele ‘Ta’ in which the tongue tapped the palate.

‘Sorry, baas,’ she said, in a voice that, he thought, was not without mockery. ‘You have to go,’ she said to him.

Gone were his ambitions of finding work as a train driver for the Rhodesia Railways, gone Abednego the Great Colonizer, the Cecil John Rhodes, the Christopher Columbus. He had begun to imbibe his brother’s dream; square and bold, black and white, clear lens; but now, Thandi smogged his vision. He spent his days lying on his camp bed in Emakhandeni hostels, which he shared with his Uncle Lungile and Cousin Solomon, huffing in reverie; or otherwise prancing about on the narrow cement corridors outside, giving dramatic little damoiseau-en-détresse sighs in response to his uncle’s increasingly exasperated requests that he come in to the Sun Hotel to apply for the position of dish washer, where he could work his way up to the position of a kitchen manager, just like he, Uncle Lungile, had and Solomon one day would.

He began hounding poor Thandi, for as far as he was concerned, it was she who hounded him. He was indefatigable in his pursuit, making him reckless with the wad of cash his Baba had packed him off to Bulawayo with – a rare gesture of love that had made him kneel before the old man’s feet. He came each day to Ticki-Tai and stuffed Thandi with chicken pies, showering her with countless bottles of Fanta, until she proclaimed an aversion to pastries and fizzy drinks. He chased after her as one pursues conquest. No, he did not want to forage towns, cities and countries. It was the soft hills of her breasts he longed to scale, the mountains of her buttocks he longed to conquer. He longed to tour the umbra landscape of her body, to discover crevices and fault lines hitherto unknown even to her, to be the first to clamber between the plateaus of her thighs and slide his flag into her summit, naming it like a god, just like Da Gama or Columbus or Livingstone or Rhodes; his own Wonderland.

‘Yes,’ she said, finally, to seeing him outside of the stifling confines of Ticki-Tai – where they were chaperoned by the glares of the Indian woman – though I imagine her eyes must have fluttered from weariness rather than delight.

How to explain to her that he, too, was fatigued? Tired of obsession, drained by mania, enamoured of revolt? Never mind that her surrender was without enthusiasm, a victory still demanded a victory dance; so that later, alone in the communal bathroom of the hostel, he would bend his bony legs, click his fingers and bob-bob-bob to the floor.

‘There is a soccer field, down the road, just around the corner from here, on Second Avenue. Meet me there tomorrow, during your lunch break?’

She checked that there weren’t any customers lurking in the aisles before she replied, ‘Listen. Listen, I’m not one of your makhaya girls, OK, your rural girls you just see and profess love to, and then take into the bush to fuck. OK?’

She said fuck in English. He gaped at her. Such a vulgar woman! Were hers really the ranges he wanted to colonize?

‘You makhaya boys need to learn some manners,’ she continued. ‘I’m not some piece of meat you just happen upon and just prod prod to your liking. I’m an Angela Davis and you’ll respect my feminality. OK?’

He wanted to ask, Who is Angela Davis? Is she your mother? Is your mother Angela Davis? Why does she have a white person’s name? She looked pissed off, though, so he just nodded.

She regarded him out of the corners of her eyes. ‘You ask a cultured girl out for lunch. And afterwards, a play.’

‘Hmmm.’ He pretended to be considering this, though his heart was in his throat. He had no idea where to take her, what she expected out of lunch and play. What sort of play was this? Did she mean playing under the covers? Was she propositioning him?

‘I can get us some nice food from the Sun Hotel,’ he said finally. ‘And afterwards we can … play.’

Her eyes lit up. ‘The Sun Hotel … yes, that’s actually a brilliant idea.’

‘No no, I didn’t mean take you there, I mean, you know no muntus are allowed there, right? What I meant was that my uncle, I mean I could get us food from the kitchens and then we could go somewhere nice like maybe Centenary Park and sit under the trees with a blanket …’

‘Don’t be ridiculous,’ she said. ‘That sort of thing is for people who have nowhere proper to go, and then they end up trying to grope one another behind the bushes. Meet me outside Ticki-Tai on Saturday after my shift. Two p.m. sharp. And don’t keep a girl waiting.’

The days leading up to Saturday were long, and unnecessarily hot and sticky. He sweated a lot. Cousin Solomon stole a tin of homemade relaxer from Uncle Lungile’s room that smelled strongly of raw eggs. Abednego watched tentatively through a piece of broken mirror as Solomon smeared it all over his kinky hair.

‘Are you sure it won’t fry my scalp or burn my hair or anything?’

‘Promise always, cousin! I’m just gonna let it sit for a few minutes, then wash it off, and then, trust me, when your girl sees you, she won’t be able to take her eyes off you!’

His scalp itched after Solomon washed off the mixture, and it began to tingle when his cousin greased his hair with sticky gel and then combed it back so it would lie flat; but the relaxer hadn’t set properly, so his hair rose in a curvy bump, sweeping up and away from his face.

‘Are you sure I look OK, cousin?’ he said, tilting his head from side to side, appraising the shiny do. ‘Isn’t my hair supposed to lie flat? What’s this bump?’

‘Ah, no, cousin, this is the pompadour conk! You look like a black Elvis Presley!’

‘Who’s this Elvis Presley and why must I look like him?’

‘Never mind, you look like an American rocking and rolling star, that’s all. We’ve washed the rural off you, cousin. You’ve become the kind of man city girls love. Your girl’s eyes are gonna drop when she sees you!’

Saturday arrived, and my surrogate father found himself standing outside Ticki-Tai at the appointed hour, two p.m. sharp, an arm wrapped around the parking meter, the other cocked on his hip, the pompadour conk flourishing up and away from his face. Indeed, at first, when Thandi emerged, dressed in a long, backless floral sundress and in the company of not one, but two young men, one of them white, she almost didn’t recognize him. She stood there appraising him, and then, just as a smile began to spread across his face, she threw back her head and laughed.

It turned out he didn’t look like a rocking and rolling star and, what was worse, the date was between him and Thandi … and the two young men – Frankie, whose face ripened under his glare, and Mvelaphi who, sniggering, kept calling him ‘merry andrew’.

Abednego wanted to grab Thandi as they piled into Frankie’s sky-blue Ford Anglia and shout, What kind of date is this? Who are these people? Is it because I don’t have a car? But he just got in, Thandi settling in the front seat with Frankie, leaving him to squash up against Mvelaphi in the back.

In this way, they drove to the Sun Hotel, my surrogate father scowling ineffectually. When they pulled up in front of the grand entrance doors, out they bounded, he trailing behind, up the steps and across the lobby, ignoring the hushed whispers of the white guests as they hastened into the hotel restaurant, where Frankie, who kept clasping and unclasping his hands, cleared his throat and announced to the brunette hostess that they had a reservation. The hostess paused, looked from Frankie to Thandi to Mvelaphi – her eyes resolved into tiny slits when they settled on my surrogate father – and back again.

‘I’m sorry, sir, but I … we don’t allow natives in this establishment …’

Abednego looked about him sheepishly. Balding and permed heads had risen from the restaurant bowls to stare at them. But the other three seemed neither surprised nor flustered.

‘Why?’ said Thandi. ‘Why are you sorry? What, exactly, are you sorry for?’

The hostess stumbled back as though she’d been slapped. ‘If you don’t leave, I’m afraid I’ll have to call security …’

As though triggered, Thandi, Frankie and Mvelaphi strode past the hostess into the restaurant, and began manoeuvring from table to table, grabbing food from the guests’ plates. The diners began to yell and shriek, some attempting to shimmy off their chairs, while others flung napkins at the disrupters.

‘Citizens against the Colour Bar!’ the three yelled, before stuffing Beef Stroganoff and Peach Melba, Salisbury Steak and Eggs Benedict, Chicken Marengo and Waldorf Salad into their mouths.

‘Say yes to black!’

‘Citizens against the Colour Bar!’

‘Say yes to black!’

Outside, sirens could be heard in the distance. Upon hearing the wheew-wheewing, the three Citizens against the Colour Bar made a dash for the exit. Thandi shoved Abednego, who had been standing by the restaurant entrance all along, and tugged at his sleeve.

‘Run!’

He raised his head just then, and glimpsed, peeping through the double doors at the other end of the restaurant, the mortified face of his Uncle Lungile, and his astonished Cousin Solomon next to him. He flinched, turned and fled.

I haven’t heard my surrogate father guffaw like that in a long time! I have been replaying our scene this afternoon in Mama Agnes’s living room, where I found him when I got back from town; the way he threw back his head and roared when I reminded him, as I handed him a glass of Bell’s, which he quickly downed, what he told me yesterday about his first date with Thandi. It was a loud, startling sound, so full and wild and free.

I found myself laughing too, like a fool, even after the man treated me like shit under his boot this morning at the shebeen, even after all I had done for him, shuwa, printing posters of the boy’s face and accompanying him on his community search. But I couldn’t help it, it pleased me to see him like that; I’ve only heard him laugh like that with Bukhosi. And now there he was actually laughing like that with me!

‘So, what happened between you and Thandi?’ I asked, chuckling. ‘Where is she now? How come you ended up with Mama Agnes?’

The man changed, just like that, nje. The laughter died in his throat. He suddenly remembered that it was Tuesday, and he was supposed to pick up some cooking oil for Mama Agnes from a friend who works at Buscod Supermarket in town. He stood up, with great effort, for he’d been drinking heavily, first the beer at the shebeen, and now my faithful dose of whisky. I rose with him, and we just stood there, in the tiny space between the sofas, he adjusting the waist of his trousers, staring at the floor, me biting my lip, watching him. He looked suddenly so weary. I wanted to reach out and clap him on the shoulder, and to apologize, for I felt somehow responsible for his sudden despondency. But I dared not touch him. I don’t know if I could take his rejection.

I still can’t believe what he told me yesterday, though; to actually think Mvelaphi, that black chap, the Citizen against the Colour Bar, is none other than our Minister of Mines, the Hon. M. Mpofu. It’s hard to imagine the man as some sort of young, impassioned anarchist; he’s now as conservative as can be, a government yes-boy with the rolls of fat clinching his abdomen like a tyre, and the requisite eighteen-bedroom mansion, private jet and three mines, not forgetting his very own soccer team – all paid for, of course, by his modest public servant’s salary … If only Thandi could see him now! He’s nowhere near that Citizen against the Colour Bar who accompanied her and my surrogate father on some seditious business at the Sun Hotel.

After Frankie had dropped the three of them off at a shabby building on Customs Avenue, my surrogate father, still overwhelmed by the protest he had inadvertently taken part in, was disappointed to discover that Thandi didn’t want to play after all. Not play play. Instead, she took him to what she called a play.

The room was cloaked in gloom. My surrogate father remembers a pair of tiny windows hugging the ceiling, but he had to struggle to make out the faces around him. He couldn’t look for too long because the stares he received back were hostile.

‘What you looking at, yellow face?’

‘You like what you see, heh?’

‘Who sent you?’

Yellow face! No wonder Frankie had dropped them off in his car but refused to come in. My surrogate father studied the floor and followed Thandi’s feet. She was busy exchanging hugs with these strange people, laughing and talking in hushed tones, and he, he had to follow her like her puppy dog. Worse, she seemed to have forgotten him, and was instead busy standing in the crook of Mvelaphi’s arm with her elbow resting on his shoulder. At one point, she tugged at Mvelaphi’s waistcoat, playful like, in a way that my surrogate father longed for her to tug at his chest hair.

A hush descended, heralding the start of the play. There was nowhere to sit but on the floor, and my surrogate father was surprised to find Thandi next to him, warm in the pack of bodies. She caught his eye, smiled and clasped his hand. Mvelaphi, who had remained standing, noticed and stared long and hard.

‘Viva to the struggle!’ yelled Mvelaphi suddenly, his eyes twitching, making Abednego jump.

‘Viva!’ the crowd roared back.

‘Majority Rule Now!’

‘Viva!’

‘Down with Smith and the Colonizers!’