6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

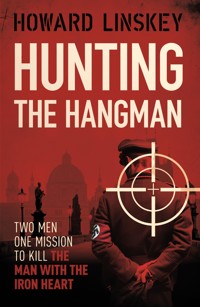

TWO MEN... ONE MISSION... TO KILL THE MAN WITH THE IRON HEART Based on true events, this gripping historical thriller is the culmination of Howard Linskey's fifteen-year fascination with the attempted assassination of Reinhard Heydrich, the architect of the Holocaust. With a plot that echoes The Day of the Jackal and The Eagle Has Landed, Hunting the Hangman is a thrilling tale of courage, resilience and betrayal. The story reads like a classic World War Two thriller and is the subject of two big-budget Hollywood films that coincide with the anniversary of Operation Anthropoid. In 1942 two men, trained by the British SOE, parachuted back into their native Czechoslovakia with one sole objective: to kill the man ruling their homeland. Jan Kubis and Josef Gabcik risked everything for their country. Their attempt on Reinhard Heydrich's life was one of the single most dramatic events of the Second World War, and had horrific consequences for thousands of innocent people.2017 marks the 75th anniversary of the attack on Heydrich, a man so evil even fellow SS officers referred to him as the 'Blond Beast'. In Prague, he was known as the Hangman. Hitler, who dubbed him 'The Man with the Iron Heart', considered Heydrich his heir, and entrusted him with the implementation of the 'Final Solution' to the Jewish 'problem': the systematic murder of eleven million people. 2017 marks the 75th anniversary of the attack on Heydrich, a man so evil even fellow SS officers referred to him as the 'Blond Beast'. In Prague, he was known as the Hangman. Hitler, who dubbed him 'The Man with the Iron Heart', considered Heydrich his heir, and entrusted him with the implementation of the 'Final Solution' to the Jewish 'problem': the systematic murder of eleven million people.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

HUNTING THE HANGMAN

May 1942: Two assassins trained by the British SOE parachute into occupied territory to kill the man ruling their homeland. Their target is SS Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich, the Hangman of Prague, architect of the Final Solution. Even fellow Nazis call Heydrich the Blond Beast but not everyone in the resistance wants him dead, when reprisals could lead to the deaths of thousands. Can two men really kill Hitler’s Heir and evade the biggest manhunt in the history of the Third Reich?

Hunting the Hangmanis a tale of courage, resilience and betrayal with a devastating finale. Released on the eve of the seventy fifth anniversary of Operation Anthropoid and based on true events, the story which reads much like The Eagle Has Landed and The Day of the Jackal is the subject of two new big-budget movies, Anthropoid and The Man with the Iron Heart.

About the author

Howard Linskey is the author of three novels in the David Blake crime series published by No Exit Press: The Drop,The Damage and The Dead. Harry Potter producer David Barron optioned a TV adaptation of The Drop, which was voted one of the Top Five Thrillers of the Year by The Times. The Damage was voted one of The Times’ Top Summer Reads. He is also the author of No Name Lane,Behind Dead Eyes and The Search, the first three books in a crime series set in the north east of England featuring journalists Tom Carney and Helen Norton, published by Penguin.

Originally from Ferryhill in County Durham, he now lives in Hertfordshire with his wife Alison and daughter Erin.

howardlinskey.com

@howardlinskey

PRAISE FOR HUNTING THE HANGMAN

‘This is a first-rate thriller and a realistic fictional account of the real events that shook the world at the height of WWII. Hunting the Hangman is thought provoking, exciting and clearly a labour of love for the author – a genuine joy to read’ – Paul Bk, Goodreads

‘A brilliantly researched and written book and one that tugged at my emotions like no book has done for a long time’ – Diane Abrahamson, Goodreads

‘Redolent with authenticity this book is based on historical accounts which have been fictionalised to help bring the characters to life. Well paced and exciting the characters are credible and beautifully drawn and the book deserves attention and to be read. Highly recommended’ – Greville Waterman

‘This is a terrific read which grabs and keeps you engaged from first to last, intelligent, well written, with excellent characterisations throughout… I very much enjoyed it’ – John McCormick

PRAISE FOR HOWARD LINSKEY

‘Linskey delivers a flawless feel for time and place, snappy down to earth dialect mixed in with unrelenting violence and pace. A Tyneside Dashiell Hammett to put Martina Cole firmly in her place’ – Times

‘The Drop is chosen by Peter Millar in The Times as one of his Top 5 crime thrillers of the year’ – Times

‘This is splendid stuff. It is further proof that Linskey (whose The Drop burst on to the crime scene with incendiary force in 2011) is one of the most commanding crime fiction practitioners at work today’ – Financial Times on Behind Dead Eyes

‘This is one of those books that I open intending to just taste it and a few hours later find myself reaching the last page. Linskey’s deceptively simple and mild style conceals a powerful punch’ –The Literary Review

‘Linskey could turn out to be very good indeed’ – Daily Mail

‘Howard Linskey has staked out the North East as his territory. Linskey has a light touch and exuberantly memorable storytelling’ – Sunday Express

‘This is a well-crafted crime story’ – Sydney Morning Herald onNo Name Lane

For Alison & Erin

Hitler’s heir is in Prague.

He is going to kill eleven million people.

Two men have sworn to assassinate the Hangman.

Even if it costs them everything.

Introduction

I can vividly remember the moment when this book began to take shape, in my mind at least. Back in the year 2000, I came home from my day job and turned on the History Channel half way through a documentary on the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich; a man I admit I was only dimly aware of.

By the end of that programme, I was hooked on the tale of Operation Anthropoid, one of the most thrilling and extraordinary missions of the Second World War. I started devouring books on the Third Reich and the SOE, trainers of Heydrich’s would-be assassins, plus anything I could get my hands on about the Nazi occupation of the Czech capital and the mission to kill the Nazi general. I was determined to recount this story in a novel.

The cast of characters features virtually every senior figure in Nazi Germany, as well as Winston Churchill, the Czech President in exile, Eduard Beneš, the head of his secret service, and the incredibly courageous members of resistance networks in Prague, who lived under constant threat of exposure, torture, and summary execution, and of course Gabčík and Kubiš, the men chosen for the mission. I flew to Prague and went to the key locations in this book, including the Church of St Cyril and St Methodius; now a shrine to the men and women involved in this story, visited by thousands from all over the world each year.

Reinhard Heydrich is perhaps not as well-known as other leading Nazis like Himmler, Göring, Hess, Bormann or Goebbels but he was an immensely powerful, much-feared, senior figure in Hitler’s inner circle and considered his eventual heir. Heydrich was Heinrich Himmler’s deputy and the head of the Reich Main Security Office, which oversaw the Gestapo. He was also Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia, which made him dictator of the former Czech territories, holding the life or death of its entire Slav population in his hands, ruling over them all from Hradčany Castle and executing so many (ninety-two in his first three days and thousands were to follow) he became known as ‘The Butcher of Prague’ and ‘The Hangman’. He is also universally acknowledged as the true architect of the Holocaust. Hitler called him ‘the man with the Iron Heart’.

What struck me most about Reinhard Heydrich was his lack of compassion, empathy or need for friends of any kind. Even in the SS he was known as ‘the blond beast’, yet he was not without talent. Heydrich was a virtuoso violinist and an expert skier, an Olympic standard fencer and a man who flew combat missions during the early years of the war, so he did not lack courage. His obvious abilities were almost entirely devoted to his own ruthless self-advancement, however. When he was tasked with the extermination of an entire race by Adolf Hitler, it seems he never once doubted the morality of the undertaking, merely fretting about the length of time it would take him to accomplish the systematic murder of eleven million men, women and children of Jewish origin. At Wannsee, Heydrich chaired the only meeting from which minutes have survived to prove genocide was the Nazis’ preferred ‘final solution’ to the Jewish question.

If I found Heydrich to be a fascinating, albeit almost wholly evil character, I was just as intrigued by Josef Gabčík and Jan Kubiš, the men who volunteered to kill ‘the Hangman’, for entirely different reasons. These two incredibly brave individuals risked everything to strike back on behalf of a defeated nation, in a move designed to preserve its very existence, and the more I learned about them, the more determined I became to tell their story.

It took me three and a half years to research then write the first draft of Hunting the Hangman. The book secured me a literary agent and a year or so later we were sitting down with an editor interested in publishing the book. I then became bogged down in interminable rewrites, including the creation of fictitious episodes that ‘fleshed out’ the story, partly at the behest of the publisher and partly because I was trying to second guess what he wanted, which is always a risky business. I ended up with a bloated, part-fact, part-fiction novel that didn’t really work and, along the way, the publisher’s interest waned.

Undeterred, I went on to write six more books and, when each of them in turn was published, I promised myself I would one day return to this story and finally do it justice. Prompted partly by the seventy fifth anniversary falling in 2017 and the release of not one but two Hollywood movies (Anthropoid and The Man with the Iron Heart that no matter how good, could not possibly tell the whole story), I finally put aside the time to do this. I blew the dust off Hunting the Hangman and rewrote it meticulously, removing every fictitious part of it and simply sticking to the core story. To the best of my knowledge, everything that happens in this book actually occurred, though I obviously had to imagine dialogue between the characters and I took one liberty, by setting a scene in Kutná Hora that likely happened elsewhere in reality. When you reach that point in the book you will realise why I found this location irresistible.

The story of the attempt by Gabčík and Kubiš to bring down one of the most powerful men in the Third Reich and its terrible aftermath needed no other embellishment from me. Thankfully I found a publisher in No Exit who agreed and shared my fascination with Operation Anthropoid, for which I am supremely grateful. So here it is; one of the most exciting, exhilarating, dramatic and devastating incidents of the Second World War and all of it true. I hope you find this story as intriguing as I do.

Howard Linskey – May 2017

Cast of Characters

Josef Gabčík & Jan Kubiš: chosen to carry out the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich for Operation Anthropoid

Reinhard Heydrich: SS OberGruppenführer, Reichsprotektor Bohemia and Moravia, Chief of the RSHA (Reich Main Security Office), Himmler’s deputy, architect of the Holocaust

Anton Svoboda: originally selected for Operation Athropoid

Eduard Beneš: Exiled President of Czechoslovakia

Edward Taborsky: Private Secretary to President Beneš

František Moravec: Head of the Czechoslovak Secret Service in exile

Emil Strankmüller: Major; Moravec’s deputy; recruited Kubiš and Gabčík for Operation Anthropoid

Winston Churchill: British Prime Minister

Anthony Eden: British Foreign Secretary

Ron Hockey: Flight Lieutenant, RAF; pilot of Halifax Bomber used to parachute Gabčík and Kubiš into occupied territory

Anna Malinová: girlfriend of Jan Kubiš

Liběna Fafek: girlfriend of Josef Gabčík

Paul Thümmel: ‘Agent 54’ – German double agent who spied for Czech secret service

Silver A Team:: Lieutenant Alfréd Bartoš, Sergeant Josef Valčík & Corporal Jiří Potůček

Silver B Team: Vladimír Škacha & Jan Zemek

Outdistance Team: Lieutenant Adolf Opálka, Sergeant Karel Čurda & Corporal Ivan Kolařík

Bioscope Team: Sergeant Josef Bublík & Sergeant Jan Hrubý

Tin Team: Sergeant Jaroslav Švarc & Sergeant Ludvík Cupal

Jindra Resistance: Ladislav Vaněk, Jan Zelenka, Network Prague : ‘Aunt Marie’ Moravec, Ata Moravec, František Šafařík, Josef Novotný

Father Vladimír Petřek: Church of St Cyril & St Methodius

Adolf Hitler: Führer, Nazi Germany

Rochus Misch: Hitler’s bodyguard

Heinrich Himmler: Reichsführer SS

Walter Schellenberg: Head of the Reich’s Foreign Intelligence Service

Karl Frank: State Secretary Bohemia and Moravia – Heydrich’s deputy in Prague

Martin Bormann: Adolf Hitler’s private secretary, head of the Reich Chancellery

Adolf Eichmann: organiser of Heydrich’s Wannsee Conference

Heinz Pannwitz: Head of Anti-sabotage Section Prague Gestapo

Max Rostock: SS Hauptsturmführer tasked with destroying Lidice

Lina Heydrich: Wife of Reinhard Heydrich

Johannes Klein: Heydrich’s driver

1

‘The people need wholesome fear.

They want to fear something.

They want someone to frighten them

and make them shudderingly submissive’

Ernst Röhm, Head of the SA (Hitler’s Brown Shirts),

Assassinated by the SS on the Night of the Long Knives

Aston Abbotts, Buckinghamshire, Autumn 1941

‘So it’s murder?’ he asked reasonably.

‘Not murder, no,’ his president answered.

‘An assassination then,’ František Moravec held up his hands to indicate he had no objection to this, ‘just so we’re clear.’

‘Call it what you will but never call it murder,’ answered Beneš, ‘an execution perhaps or you could name it war,’ the exiled Czech leader told the head of his secret service, ‘if you prefer.’

‘Let’s call it justice?’ suggested Moravec but Beneš was already tired of this.

‘Suppose we simply call it what must be done.’

Moravec seemed happiest with that definition for he had merely been testing his leader’s resolve. ‘But how to do it?’ he mused, as if asking himself this and not Beneš.

‘How indeed?’ said Beneš. ‘That part I will leave up to you.’

The President looked smaller here with everything hemmed into his office in the old abbey at Aston Abbotts. His desk was an unfeasible clutter of transcripts, memos and telegrams and he seemed reluctant to allow any of them to be filed away. Every available inch of it was covered in paper. A large bookcase was fixed to the wall behind him and it towered above his shoulders but there was no space here for books. It too had been commandeered for the papers of state. They were piled high in horizontal stacks or wedged together vertically, in such close order that their spines had warped under the pressure of the confined space they occupied.

‘It won’t be easy,’ said Moravec.

‘I understand.’

‘You want to send men back to our conquered capital to kill the most senior Nazi in the country,’ said Moravec, ‘a man with the rank of a general who rules like a king. Heydrich isn’t just a Nazi puppet. The man ranks second only to Heinrich Himmler. He is Hitler’s personal favourite.’

‘I would go further,’ said Beneš. ‘I’d say it is likely Hitler regards Heydrich as his heir.’

‘The next generation,’ agreed Moravec, ‘of the Thousand-Year-Reich he has promised his people.’

Beneš suddenly rose from his seat and crossed the room. It was a restless movement with no specific purpose behind it. He stared out of his window at the garden of his English bolthole. The village of Aston Abbotts was not a new dwelling place; it was mentioned in the Domesday Book but you could walk its entire length in a little over five minutes. There were neat little nineteenth century houses here, tied cottages, a couple of ancient pubs and a Norman church with a stone memorial to an earlier conflict. The former abbey was as good a spot as any for the exiled President’s hideaway. Guards patrolled the area discreetly or held back in the shadows provided by the dark grey stone of the house – and at least one would be in permanent occupation of the tiny, picturesque lodge, a thatched and white-washed cottage by the gate. ‘Then it would be an even bigger blow,’ he told Moravec purposefully, ‘one they would feel in Berlin.’

‘What about the British?’ asked Moravec. ‘Are they going to help us?’

‘They will,’ said Beneš firmly and Moravec realised his President had yet to ask Churchill for his blessing. ‘I know this is no ordinary mission, František,’ Beneš continued, ‘our target will be heavily guarded.’

‘An army couldn’t kill Heydrich,’ said Moravec and his President seemed concerned he might have already admitted defeat until he added, ‘but two men might.’

‘Only two?’

‘With help from others.’

Beneš seemed satisfied Moravec had already been giving the mission serious thought. ‘And you could find me such men?’

‘There are many who wish for nothing more than the opportunity to continue the struggle against the Nazis, so yes, I can find you two men.’ He spoke as if that was the easy part.

‘But they must be the right men?’ Beneš realised what he was getting at.

‘We’ll only get one chance. Fail and Heydrich won’t travel anywhere again without an armoured convoy around him.’

‘Thousands came to England to continue the struggle when our country fell,’ Beneš reasoned, ‘there must be exceptional men among them.’

‘There are,’ Moravec agreed.

‘Get them then,’ Beneš ordered and he turned back to the window to give Moravec his cue. Their meeting was over. The rain that had been threatening for hours finally came and thick droplets padded against the window outside. Moravec made as if to leave.

‘František,’ Beneš stopped him, ‘make sure they understand.’

‘That they might not be coming back?’ and Beneš nodded. ‘Good men would know that already,’ he assured his President.

2

‘Set Europe ablaze!’

Winston Churchill’s instruction to Hugh Dalton, Minister for Economic Warfare, on the creation of the Special Operations Executive (SOE), July 1940

Josef Gabčík was playing at soldiers again. He had just leapt from an imaginary landing craft, an L-shaped jetty yards from a Scottish beach, into an admittedly very real sea and was now wading towards the shore, chest deep in the salty surf.

Using his peripheral vision, he noticed he was at the head of a dozen men who had jumped into the water. There were a few gasps from his comrades, and a number of loud curses at the initial shock of the cold ocean, but the swearing strangely cheered him, coming as it did in his native tongue. He ignored the icy chill of the water, the salt in his eyes and the burn of the pack’s straps on his shoulders, and pressed on.

Gabčík held his rifle high above his head with both arms, trying not to stumble on the uneven, shifting surface of the seabed, bending forward to allow for the 40lb pack full of rocks that was strapped to his back. He advanced as quickly as the buffeting of the ocean would allow.

A few more steps and he was pulling himself free from the grip of the water, which tugged at his soaking fatigues, weighing him down, and he became instantly aware of the harsh cries of the two British NCOs waiting on the shingle.

‘Move yourselves! Move yourselves!!’

‘Get out of there now! This is not a fuckin’ tea dance!’

Both men were with the Special Operations Executive and, with the sadistic enthusiasm to which Gabčík had become accustomed, they were hell bent on turning him into a commando. As soon as he was free from the surf, he sprinted across the cove in a stumbling run, feet sinking into the shingle, running like a child trapped in a bad dream who cannot get away fast enough. His lungs heaved under the exertion and the breath caught in his throat, before it was expelled in little clouds of vapour that were immediately left behind him as he powered forward.

Now he was almost there, he could make out the giant shadow of the cliff face in front of him, even though his head was down to avoid the pretend bullets of an imaginary machine gun they were assured was in the cliff tops.

‘Diggah! Diggah! Diggah!’ screamed the Glaswegian corporal. ‘Yer fuckin’ deed Kubiš!! Unless you get yer bastad heed doon!!’

Like Gabčík, Jan Kubiš would barely have understood a word from the Scotsman’s mouth but he would have easily picked up the meaning. That’s what it was like here; a few half comprehended phrases of command were all they had to cling to. That and a desperate yearning to one day return to their homeland to fight the Germans who occupied it.

Till then their world was a completely foreign place. These defeated Czech soldiers awoke each morning in a Scottish barrack block in Mallaig, to be ordered around by officers, they could just about understand. As for the NCOs, they were a grim bunch of hard soldiers, with varied and unusual communication skills. Everything was barked or yelled in a guttural holler. That was fine, it was the same the world over and Gabčík was a six year veteran of the Czech army, when it had an army, but the few words of English he and his comrades picked up were torn and tortured beyond understanding by these career soldiers. The NCOs were cursing now as some of the men made a slow and unsteady progress across the beach.

‘What’s wrong with you lot? Are you all pissed or something? Gabčík! You short-arsed little runt! All you’ve managed to prove is your legs are not long enough to get you where you need to be!’

With these inspiring words of encouragement ringing in his ears, Gabčík finally reached the cliff face at a full sprint, almost slamming into it. As always, he did not let up until he was at the very end of his task.

He leant against the rock gasping for breath, a few of the quicker, fitter men having arrived at roughly the same time. Gabčík was pleased that, at twenty-nine, he was among the first there, could still hold his own. His short frame was stocky and powerful, making him capable of feats of strength that would defeat larger men. Gabčík had a volatile temper that could cause embarrassment in civilian life but served him well during a hail of bullets or shelling. And he had already fought, and killed, Germans.

He had beaten Kubiš there by a yard and felt no less respectful of the slightly younger man for it. Jan Kubiš was still a fine soldier and theirs a good friendship, forged under the most maddening of circumstances. As the NCOs got the men together he noticed Kubiš, like him, was quickly recovering.

‘That woken you up?’ asked Gabčík.

Kubiš was breathless. ‘There’s nothing like a nice walk along the beach.’

The corporal immediately rounded on him. ‘Save your breath, you’re gonna need it.’

The Scottish corporal was away again. This time it was an unrelenting rant at their inability to cover the yards of beach-head within the desired time; a limit Gabčík was savvy enough to assume would always be a few seconds quicker than their fastest man, such was training, such was the army.

‘Now you are going to redeem yourselves with a nice gentle climb!’

The NCO cajoled the men into one final effort, an eighty-foot vertical ascent of a sheer rock face.

‘Make it look good or we will throw you off this course. You can go and dig potatoes with the Land Army girls. I’ve seen a couple of them up close and they are a fucking sight scarier than you lot. Now move it!’

And so Gabčík climbed, for he knew it was his only way back into the war. With three and a half thousand other Czechs, Jan and Josef had endured a perilous sea journey to England. The Czech Brigade based itself at Leamington Spa and the two veterans had experienced the boredom of army camp life there with no imminent prospect of a return to action. After a year of frustrated inactivity, the request had gone out for volunteers to join the SOE. Neither man hesitated and they were on the move again; to Mallaig and the six week commando course that was more than two thirds through by the time Gabčík found himself stranded half way up the cliff face.

He clung perilously to the rock; red face pressed against the stone, hissing profanities to himself in Czech. He was about to fail his assignment and would likely be thrown off the course as well, and it was all down to his own stupidity. Had he listened to the instructor when he urged them all to use proper footholds and not just grip the rope with their hands like they always did? The cliff face was too high for that. Gabčík’s biceps burned and the small of his back throbbed with the effort required just to stay still. He tightened his grip round the length of grey, wet rope that hung from the upper most point of the crag and rubbed the skin from the palms of his hands.

Moments ago he had admitted to himself he was stuck, unable to go back down and seemingly stranded without the footholds needed to carry him the extra forty feet to the summit. All about him lesser men than Gabčík were making steady if unspectacular progress. The humiliation was too much and it spurred him into action. Rage welled up inside him and it slowly replaced the fear and the doubt; he cast his eyes to the left and spotted an outcrop that was tantalisingly out of reach. If he could just spring from his current spot, he might get enough leverage with the rope to propel himself onto this toehold. Gabčík hesitated for a moment, closing his eyes and summoning up his anger, the storm that had always served him so well in battle. He had to make it and fear of falling must not be allowed to prevent him. If he did not make the jump he could not move higher. If he did not climb higher he would never reach the top and would not then pass out of the commando course, to join the other would-be saboteurs – his only opportunity to engage the Germans and remove the shame he felt at abandoning his country. And so, he jumped.

For a second there was nothing but air around him, then his left foot connected with the rock, his left hand scrabbling for an indent, and it held. He clung there, the rope drawing fresh blood from the base of his thumb, which he contemptuously ignored. Gabčík barely paused. Instead he hauled himself higher and propelled his other hand into the air. He could not see the ledge above him but grasped it firmly and pulled his body upward again, stretching out his right foot till he connected with a large outcrop. And so on it went; Gabčík rising, cursing and rising again, using his self-recrimination to push him on, catching up with the others.

He remembered the last thing the Scottish corporal had told them in the briefing.

‘When you reach the top of the cliff I want you to give me a battle cry. Let me hear the roar from each of you. Pretend I’m a Nazi machine gunner. I want you to scare the shit out of me!’

Gabčík took him at his word and shot over the edge of the cliff with the most bloodcurdling cry imaginable. Even Corporal Andy Donald was impressed.

Gabčík careered past him at a full sprint, only stopping at the rallying point, which was already beginning to fill up with his fellow Czechs, who sat on the ground next to, or on top of, their packs. One of them was foolish enough to let out a laugh at Gabčík’s crazed countenance and they exchanged a handful of insulting words. That was it. Without pausing for a moment, Gabčík whirled on his mocking colleague and smashed a fist squarely into his chin.

Corporal Donald immediately began to shout new orders, to have Gabčík dragged away from his hapless victim. Gabčík was in one of his private worlds, all red mist and hot rage, and Donald had seen him like this before. It could start with something quite trivial, an upended mug of tea or the frustration borne of an inability to complete something; assembling a Sten gun blindfolded perhaps. Corporal Andy Donald was a hard man, scared of nobody, but even he recognised this soldier had a truly awesome temper, the kind that, if harnessed correctly, would take him through any obstacle without a second’s hesitation; bullets bouncing around him would go unnoticed. It would take a lot to stop Josef Gabčík if his mind was set.

It took three of Gabčík’s comrades to haul him away. That is what happens when you train men to kill but don’t let them anywhere near the enemy, thought Donald.

‘Alright, that’s enough! Enough!!’

Had Gabčík really seen Nazis as he reached the top of the cliff? Probably, knowing him. For a second Corporal Donald almost pitied the poor bloody Germans.

3

‘All is over, silent, mournful, abandoned, recedes into darkness’

Winston Churchill on the invasion of Sudeten Czechoslovakia

‘One more please. Please Herr Gruppenführer, just one more, with the big smile, and so! Now perhaps we have Frau Heydrich with little Heider is it? Heider yes! Heider and Klaus, and of course the little Princess Silke. We haven’t forgotten you, have we?’

The photographer cooed absurdly at Reinhard Heydrich’s baby daughter, shaking his head. ‘No, we haven’t, no!’ – she sensibly chose to ignore him.

Hauptsturmführer Zentner belonged to Goebbels’ propaganda division and his mission today was to capture the Heydrichs at home – on film at least. Reinhard had agreed to the photo call weeks ago, aware of the need to project a positive image at all times, and to every section of German society. It was part of his strategy to reach the very top. He had even consented to be photographed out of uniform, in a ridiculous pair of shorts and shirt sleeves, in order to contrast the man at home with the man of state, as Captain Zentner put it.

First, it was full silver/grey SS dress uniform, complete with ceremonial sword, at the foot of the staircase; then behind his desk, again in uniform, black this time, pretending to peruse a blank sheet of paper as his pen hovered above it motionlessly, until the click of the shutter and the flash of the bulb melted him from the frozen image he had assumed.

Now the whole family was made to cavort ridiculously on the lawns to the rear of the Panenské Břežany mansion. But the photo shoot was taking too long, as these things always did, and Heydrich’s mind was elsewhere. He had postponed a liaison with his mistress for this and began to long for the delicious friction of her even as he posed, with his children all around him, smiling inanely at the lens. Today, though, he had weightier matters to consider and he wondered what had happened to his driver. Klein had been sent back to Hradčany three hours ago to collect a batch of urgent signals. He had been told not to pause even for a cup of coffee but to return as soon as he had the papers and hand them personally to Heydrich. What on earth could be keeping the man?

Heydrich’s irritability found a target in the photographer. Zentner was a small, thin streak of nothingness with a lispy, effeminate manner, who danced round them enthusiastically as he sought the perfect picture of the Heydrichs. Too enthusiastically for Reinhard, who eyed the man contemptuously. He was convinced he was a bum boy, like that scrawny drag queen he once had the misfortune to witness in a Berlin nightclub, at a time before the Nazis had shipped out all of the fags along with the gypsies, the communists and the Jews. But hadn’t Lina already established that he had a wife? While he was setting up his tripod and cameras on the grass, and bossing his two silent and anonymous young assistants, she had trilled in a nervous, eager to please manner.

‘And is there a Mrs Zentner?’

Did she actually hold this photographer in some form of awe?

‘Back in Koblenz, yes, Frau Heydrich!’ He had called back familiarly, as if she were the wife of a sergeant.

No children though I’ll bet, thought Heydrich, probably a show marriage, to take suspicion away from his unnatural, nocturnal activities. What was Goebbels thinking, employing degenerates like this fellow? Heydrich had been told they were sending one of the best men from the propaganda division and the photos would be seen all over the Reich. There was another SS man close by with a cinematograph machine, so the ideal Nazi family unit could be displayed across a thousand film screens as well. Lina was loving every minute of it, which was perhaps why she was so uncharacteristically civil to the captain.

He remembered how she had been in a fury the day they had seen the first, sanitised newsreel footage of the Goebbels family, a prelude to the feature attraction of some Berlin cinema. There was Magda, the archetypal Aryan matriarch, seated and flanked by no fewer than six children. Her adoring husband Joseph stood at her shoulder, beaming down at her, while a rousing commentary extolled the virtues of maternity, motherhood and the glorious provision of young Nazis to serve the greater German Reich. Cut to shots of sexless young women doing exercises in a field somewhere in Bavaria. Dressed in identical white blouses and dark shorts, fine figures of Germanic girlhood one and all, they danced in synchronicity and on the spot, while the commentator told them how healthy bodies produced healthy babies and urged them to marry the right Aryan boy, and immediately begin gestating for the fatherland.

This little insight into Nazi thinking ended with a final shot of the beaming Magda, provider of life, champion producer of children. Of course, at the time of the film Joseph, the perfect family man, had been screwing Lída Baarová, the famous Czech film star, whose career he had extravagantly promised to advance. But no one was going to put that in a newsreel.

Lina proclaimed Magda to be a vain and common bitch parading herself in this manner. She had obviously forgotten this heartfelt opinion now, for she scooped all three of the Heydrich brood to her arms at once and clasped them to a more than ample bosom, as she tried to persuade them to smile for the camera. Heydrich thought it an impossible exercise as Silke was entirely uninterested and Klaus appeared to be choking on her breasts. Lina was unlikely to spot his distress, however, so entranced was she by the adoring camera.

‘Lina, you’re suffocating the boy.’

He wandered away from the scene as Frau Heydrich flushed, before trying to turn the whole thing into a joke, desperate to stifle Klaus’ already welling tears. Heydrich lost interest in this charade the moment he noticed Klein. His chauffeur was literally running towards him across the manicured carpet of lawn that divided them. The two men met a few yards from the cameras.

Klein saluted, ‘Apologies, Reichsprotektor, the signals arrived late and I had to wait for the dispatches to be decrypted.’ Klein knew Heydrich cared little for excuses but was determined to prove the delay was most certainly none of his doing.

He handed over a sealed folder containing several sheets of paper. Receiving no further instruction from Heydrich, who simply wandered away wordlessly as he scrutinised the information.

Avoiding the distractions of Lina’s wittering and the unchecked hollering of his children, Heydrich read the eastern front dispatches. It took only a moment’s perusal to realise operations were not moving quickly enough, not by a long way.

The memos contained a detailed report on the Einsatzgruppen and their daily ratios, and they were letting him down. The Einsatzgruppen were Heydrich’s personal responsibility; along with controlling the entire secret service of the Reich and running the ‘Protectorate’ of Bohemia and Moravia as the Czech territory was now known, he had volunteered for one more assignment, a pet project very close to the Führer’s heart. Only by achieving success in all three arenas could he be assured of further advancement. The top job in France was his next target, for he had noted with satisfaction how the current administration had the country far from under control. It would take the SS to subdue the French and Paris would prove the perfect stepping stone. Then, one day, the longed for call to Hitler’s bedside, when an ailing leader would publicly name Heydrich as his successor and leader of the German people. Nothing would stop Heydrich from reaching his goal but the Einsatzgruppen would have to improve, and quickly.

The majority of the three thousand men of the Einsatz-gruppen were of a civilian background, often from the professional classes; disgruntled doctors, lawyers, government officials and clerks, all sharing one trait, a fanatical belief in the semi-Darwinian theory of Nazism. Their three weeks training at Pretzsch Police School in Silesia was an indoctrination period, reinforcing the mantra of eugenics, not a lesson in tactical combat. Let the strongest survive, eliminate the weak and, of course, it is the Germans who are the strongest, the Jews occupying the lowest rung on the human evolutionary ladder. The men of the Einsatzgruppen were not being trained to fight, they were being taught to kill. These ‘Action Groups’ would go in after the first wave of German soldiers. Once the Wehrmacht had broken enemy lines and secured the area, the work of the Einsatzgruppen could begin in earnest. Under their mandate to carry out ‘Executive Measures’, they would rid the land behind the lines of undesirables, subhumans and, of course, the insidious plague that was Jewry.

And so it began; the firing squads, the hangings and the officially encouraged pogroms, carried out by non-Jewish locals under the watchful, indulgent eye of the all-conquering Germans. As the Wehrmacht swept through Soviet territory, the area behind them was being cleansed for future occupation by German settlers, who would find nothing there to disrupt their utopian lebensraum. Heydrich assured Hitler his trademark ruthlessness would be put to good use marshalling the four Action Groups that would prepare the land, and he had received the Führer’s blessing to command operations, but how long would he remain a favouriteif progress was too slow? Had he not used the same argument to oust his predecessor Von Neurath from the seat of power in Prague? How easy it had been to convince the Führer a new man was required to get the job done, that all it took was a change of personnel to fulfil his grand vision. Heydrich knew he was on dangerous ground; having promised stunning success he could hardly deliver anything less.

The noise from the photo shoot became like the buzzing of so many distant insects as he scrutinised the numbers Klein had provided. One of the memos took the form of a table, with meticulously logged figures ascribed to particular dates and locations. Along the top ran the words: Men, Women, Children, and Total. From this chart Heydrich could see, for example, that nine hundred and sixty Jews had been executed by the men of the Einsatzgruppen on such and such a day in September, outside some unpronounceable village in Lithuania; that of these, four hundred and ninety two were men, three hundred and fifty seven women and one hundred and eleven children. Heydrich skipped the majority of these specific incidents and went straight to the tables at the foot of the memo. In total forty three thousand Jews had been eliminated in that same month across the whole region, an improvement of almost twelve thousand on the previous month.

It wasn’t enough, not nearly enough!

‘Leave papa alone, Silke. He is trying to work.’

Silke typically ignored her mother and blundered on her unsteady infant legs straight into her father’s shoes, tripping over them in the process. He looked down at the bemused figure of his infant daughter blinking back up at him. Silke seemed perplexed as to why she was now sitting on her backside in front of him, so he scooped her up into his arms and he clasped the gurgling, blonde child to his chest with one arm while he continued to read the papers, now held outstretched in his free hand.

‘Who’s papa’s girl then?’ he trilled.

He was never comfortable with baby talk but Silke was the sole creature on the planet capable of reducing him to that level.

‘Who’s daddy’s favourite little girl?’ He checked another figure at the bottom of the page. Was the ratio of executed Jewish men disproportionately higher than that of the women? One would have expected almost an even spread but, judging by the quick sum he had done in his head, the women made up under forty per cent of the total number of adults killed. Were some of these Einsatzgruppen formations trying to dupe him? Allowing the women to flee while more comfortable killing off their menfolk. He was sure of it, and far from certain the men entrusted to carry out this most important work were hard enough to fulfil their mission.

Silke gurgled and a trail of dribble fell from her mouth onto the breast pocket of his shirt, staining it dark.

‘Thank you, Silke, thank you so much, you messy little girl,’ he chided but his voice was not harsh, never departing from the sing song pitch of a nursery rhyme. He would hardly have to clean it himself and had been given the perfect excuse to call a halt to Zentner’s little farce. Besides, he could never stay annoyed at Silke, his pretty little blonde princess. Heaven help the man who wanted to take her away from him when she was older.

Returning to the report he now examined the number of children eliminated. This surely was far too low. Some of these Jews bred like rats and had sizeable broods tagging on behind them. Was he really to believe the majority of the men and women killed were childless? Eleven per cent was an improbable figure. He would have it immediately questioned and investigated. The men in charge of the region were shirking their duty, letting children escape the necessary purging of Jewry. If they could not be relied upon to carry out the task he would replace them and find others who were stronger willed, without such ridiculous scruples. How often had they been told that to spare a child is only to assure Germany of a future enemy? Worse, it could allow cross breeding and the very real chance that polluted blood would be admitted into the Reich. Would they never learn? He felt he had hit upon the essential paradox that confronted these partial executioners. Even they would have to admit the folly of their acts of mercy when they thought about it closely.

Heydrich kissed his unreceptive baby daughter on the forehead before handing her back to a beaming Lina. The photo shoot was apparently over after all and Frau Heydrich appeared delighted with proceedings.

Heydrich, however, could not dismiss his anxiety over the partial failure in the east. The figures did not lie. In four months, the Einsatzgruppen had managed to dispose of just half a million Jews, by hangings, firing squads and other sundry methods of dispatch, and there were ten and a half million more to eliminate if Europe was to be entirely cleansed of Jewry. At this rate, it would take them approximately seven years to complete the job, a timescale Hitler simply would not countenance. No, this was very bad news indeed.

And there was a further complication. Two days earlier Heydrich had been alarmed to receive Himmler’s secret memo, wordily entitled Observations concerning the psychological effects of the campaign in the east. The Reichsführer SS went on to list an array of negative symptoms, associated with the trauma of such wide scale killing, on the SS men tasked with the destruction of the Jews.

While many SS men are comfortably shouldering the burdens placed on them, and a significant number relishes the accomplishment of this most important task, there has been a marked increase of late in the numbers requesting transfer to traditional, frontline combat duties, where they wrongly perceive they are facing a more equal and direct enemy. Suicide is not entirely uncommon and there have even been cases where SS men have turned murderously against their own comrades and have had to be eliminated for the protection of others. Naturally these cases have never, nor will ever, be made public. I have personally witnessed the special work being carried out and confess that it has the capacity to disturb even the strongest of wills. In conclusion, it would seem a solution is required to alleviate the psychological burden on our men. Please advise your earliest thoughts on this matter most urgently. Signed Heinrich Himmler – Reichsführer SS

Heydrich had burned the memo instantly before returning to his desk to ponder its implications.

Now, days later, he was still wrestling with the great logistical problem of processing eleven million Jews expeditiously and with the minimum of fuss. There must be an easier method than this he reasoned. A great administrative brain like Heydrich’s could surely come up with a more efficient system than the random lynching or ad hoc firing parties. Something more humane was required. That is, more humane to the killers.

It had to be done to safeguard Heydrich’s future. He was running the east like a corporation, crossing Jews off the balance sheet, but not quickly enough. Not nearly quickly enough.

Lina set Silke down and watched as she scampered after her brothers. Frau Heydrich walked adjacent to her husband, slipping her arm between his, and he noticed the bulge of her pregnancy was beginning to become visible now. Previously it had been hard to tell where the matronly figure of a woman in lower middle age ended and the early signs of maternity began.

Lina rubbed her stomach joyfully. ‘I think that it is a boy.’

They strolled slowly back to the house, the older children running ahead of them to keep up with the photographer and his assistants. The sun was beginning to reach its highest point of the day and the servants would be preparing lunch.