4,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

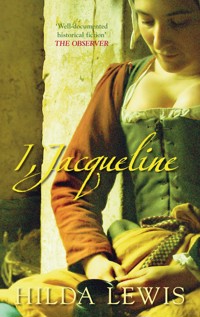

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A historical fiction that presents the life and loves of Jacqueline of Hainault, thrice married, thrice imprisoned and ransomed; the extraordinary 15th-century life of a women who endured the power politics of the courts of England, Burgundy, and France.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

To

CHERRY KEARTON

with my thanks

Cover illustration: John Foley/Archangel Images

AUTHOR’S FOREWORD

Our story opens in Holland in fourteen hundred and seventeen—nearly two years after Agincourt.

In England, the victorious Henry V is on the throne; in France the mad King Charles VI is soon to be succeeded by Joan of Arc’s Dauphin.

Count William VI, hereditary Prince of Holland, Hainault, Zealand and Friesland, is nearing his death. His heir is his young daughter Jacqueline; and his last days are tormented by this question: Will she be accepted as undoubted prince in his place?

The land is torn in two by quarrels. Certainly his own party, the Hooks, will support her; but what of the Cods, enemies of his house?

The sudden death of Jacqueline’s husband—the heir to France—leaves her without her natural protector. A new marriage must be made at once. Whom shall the young princess marry?

With this death and with this question we begin the story of Jacqueline.

Epitaph for Jaqueline

L’amour pour quatre fois me mit en mariage,

Et si n’ay sceu pourtant accroistre mon lignage,

Gorrichem j’ay conquis contre Guillaume Arklois,

En un jour j’ay perdu presque trois milles Anglais.

Pour avior mon mary de sa prison deliver,

Au Duc de Bourgoingnons tous mes pays je livre.

Dix ans regnay en paine; ore avec mon ayeul

Contente je repose en un mesme cercuil.

Four times in wedlock heart and hand I gave

And though my ancient line ends in this grave

Gorcum I won from William Arkels’ host.

Three thousand English in one day I lost.

My husband from his prison to set free,

My kingdoms all I gave to Burgundy.

Ten years I reigned in grief; content am I

In my ancestral tomb at last to lie.

PRINCIPAL CHARACTERS

IN HOLLAND

The Countess Jacqueline, Hereditary Prince of Holland, Hainault,

Zealand and Friesland.

Count William VI, her father.

Margaret of Burgundy, her mother.

John of Touraine, Dauphin of France, her first husband.

John the Fearless of Burgundy, her mother’s brother.

John the Pitiless of Bavaria, bishop-elect of Liége, her father’s brother.

John of Brabant, her second husband.

Philip the Good, her cousin; son to John of Burgundy.

Beatrix van Vliet, her half-sister.

Frank van Borselen, stadtholder of Holland; leader of the Cods.

William van Brederode, captain of her forces; leader of the Hooks.

IN ENGLAND

Henry V, King of England.

Catharine of Valois, his wife.

Henry VI, their son, the infant King.

John of Bedford, brother to Henry V, commander of the English forces in France.

Humphrey of Gloucester, his youngest brother, Protector of England.

Henry Beaufort, half-uncle to Henry V, bishop of Winchester, Cardinal of England.

Eleanor Cobham, Gloucester’s mistress, later his wife.

IN FRANCE

Charles VI, the mad King of France.

Isabeau, his wife.

Charles VII, their youngest son; Joan of Arc’s Dauphin.

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Author’s Foreword

Principal Characters

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

Chapter V

Chapter VI

Chapter VII

Chapter VIII

Chapter IX

Chapter X

Chapter XI

Chapter XII

Chapter XIII

Chapter XIV

Chapter XV

Chapter XVI

Chapter XVII

Chapter XVIII

Chapter XIX

Chapter XX

Chapter XXI

Chapter XXII

Chapter XXIII

Chapter XXIV

Chapter XXV

Chapter XXVI

Chapter XXVII

Chapter XXVIII

Chapter XXIX

Chapter XXX

Chapter XXXI

Chapter XXXII

Chapter XXXIII

Chapter XXXIV

Chapter XXXV

Chapter XXXVI

Chapter XXXVII

Chapter XXXVIII

Chapter XXXIX

Some Books Consulted

About the Author

Copyright

I

It was my mother who thought of the black ribands. She had always a strict sense of what was proper; habit would lead her to seemly behaviour though the heart remained cold. That my young husband was suddenly, shockingly dead seemed to weigh less with her than that no one had thought to find me a black gown or even to tie a mourning riband about my arm. As for myself, I was so bewildered by the suddenness that I had had no time as yet to feel my loss.

But it is like me, impulsive as I am told I am, and as I must believe I am—though the years have disciplined me more than a little—to plunge into the middle of my tale without telling my name or my parentage.

Well then, I am called Jacqueline—of Bavaria, or of Hainault, or of Holland, whichever you choose. Yes, I am that Jacqueline who, ill-fortune pursuing, set all Christendom by the ears with scandal in high places.

My father was William VI, Count of Holland, of Hainault, of Zealand and the free Islands of Friesland; my mother, Margaret of the house of Charolais, from which are sprung the great dukes of Burgundy. My father, lively and loving with his friends, could yet lay a heavy hand upon his enemies. He was renowned for his prowess in the fight—and with women. He was a friend to scholars and to poets; and in his court the laws of chivalry lingered still.

My mother is a true de Charolais—hardheaded and ambitious; she has always put the honour of her family first—the de Charolais. And she is a true de Charolais in her looks; of low stature, the eyes pale grey, not overlarge nor lustrous; but the mouth is thin rather than full and she holds it tight-pressed and did, even when she was a young woman. Whether she ever loved my father, I don’t know. She did her wifely duty but without generosity. And, perhaps one cannot blame her; for she never forgave him his women. A gentler wife might have won him; but her pride was set hard. Everyone knew about his mistresses and his bastards—and she with one child and that one a mere girl!

She never quite forgave me, either, that I had not been born a boy. She was no unnatural mother but she was not a loving one. When I behaved ill I was not only whipped but threatened also with the name of the great duke, her brother. Your uncle of Burgundy will be after you! she would cry out. Or, I am sending to my brother John. And that was worse than any whipping. For a whipping is soon forgotten; but fear breeds in the dark places of the heart. John of Burgundy was my childhood bogey and so remained throughout my life … and good cause, too. Although it was the last thing my mother desired, it was she herself that had bred in me this fear and distrust.

I feared my mother and I loved my father. He was my sun that shone. Whatever disappointment he may have felt that I was not a boy he never showed it. He loved me because I was his child; he enjoyed my childish company because my answers came pat, and my laughter, too. But most of all he was pleased because I was pretty in the Dutch style rather than in the Burgundian. When I was nine years old or thereabouts, Master Jan van Eyck painted a picture of me and my father wore it about his neck. It is lost now, like most of my treasures; but like many a lost treasure it is safe in my heart.

I see it as clearly, as though I held it before me—the round-faced child with rosy cheeks and light-brown curling hair. The eyes are dark blue—and Master van Eyck has caught the expression marvellously; they are trying not to laugh and the little mouth is buttoned up with the same desire. The small creature is well aware of the seriousness of the occasion; but for all that it is certain that the laughter must come bursting through. The chin is round and very determined for so young a child; the nose is delicate, a little tip-tilted. Altogether if I may say it of that far-off child—a pretty creature.

I cannot remember when I was not an important person. I had arrived late in the married life of my parents, though my mother was barely thirty; but sixteen years is a long time to wait and they had given up hope. I was three years old when my father succeeded to the throne of the Counts of Holland; and so I became Daughter of Holland and his sole heir.

In any court, even a small court like my father’s, a young prince is flattered and fêted; and so it was with me. Sycophants would run fawning with presents and with pretty speeches; but they turned their backs quickly enough when the wind blew cold.

I must mention one other person who played a great part in my life—Beatrix van Conengiis, my favourite woman and constant companion. My mother disliked her and would have sent her packing; but Beatrix held her position at my father’s command. He told me himself, when I was eleven or twelve perhaps, that she was his daughter—and, indeed, she had his handsome look. He desired, he said, at least one loving heart about me during his many absences; and he desired, also, her own advancement. And so it turned out. She had not been about my person but a little while when she caught the eye and the heart of the Lord of Conengiis—a match for which even my father had not dared to hope; and it did not make my mother any sweeter. From the time I was old enough to understand anything I knew that Beatrix cherished me with a never failing love … and that my mother hated her.

I cannot remember further back than my fifth year—the year of my betrothal. I was carried by mother to Compiègne to be betrothed to the second son of the King of France. There were feasts and music and masques though, shut away in the nursery with Beatrix, I never saw any. But, one thing I do remember, and that was a fit of passion in which I screamed because my father had not come. He had promised; and he was not there. It was only afterwards that I knew why he had not kept his promise to me, the only promise he ever broke. He had been bitten by a dog on his way thither. Always a lover of beasts, he had stooped to a strange mastiff in the courtyard of an inn and the creature had sprung and bitten him in the leg. And, though he sent me pretty gifts and loving messages, I would neither look nor listen but still cried out and beat upon the floor and would not be comforted.

There were many to whisper behind their hands that nothing good could come of this betrothal, for my betrothed’s father was absent as well as my own—Charles VI of France had been left behind in Paris to howl in his madman’s cell. The excitement had been overmuch for his frail body and the ever-dreaded sickness had fallen once again. But I knew nothing of that. I only knew that my father’s place was empty; and that Madam Queen Isabeau sickened me with her smell of stale perfume and sweat. My mother used no perfume at any time; and she had fallen into our good Dutch habit of soap and water. Courageous as I was and high-spirited, I was frightened of Queen Isabeau for all her handsome looks. It was not only the smell that went with her—at the French court my mother was almost alone in the sweetness of her body—but because she was tall and heavy and towered above me like a dark tree; and because her mouth was red as blood and it shut down like a trap, and her eyes flicked like a whip to make you do whatever she commanded.

John Duke of Touraine, my betrothed, was seven years old; that is three years older than I. He was good and gentle; and he showed no sign of his elder brother’s weakness in character. Louis the Dauphin, in spite of his tender years was already known for stubbornness and for spiteful ways. But John did, alas, show signs of that other weakness that would not let Louis ride a horse or even sit long in a litter without swooning. But our good Dutch food would make all well, my father used to say.

When we returned home after my betrothal John went with us to learn the ways of the people he would one day help me to govern; and I was the happiest child in the world. I did not know what a betrothal might be; but I did know that it had given me—a lonely child—a most loving companion. He would do whatever I wanted. It was I that suggested our games and he that followed. When he did not follow quickly enough I would stamp and catch hold of his dark hair; and he would gently uncurl my fingers, careful not to hurt me rather than to spare himself. When we did things that were forbidden—walk in the river when the March winds blew cold from the sea, or chase the sheep so that they ran in all directions, bleating madly—it was John that took the edge of my mother’s tongue, and the whipping, too.

I was fourteen and he seventeen when we were put to bed together. There was a great ceremony in the Hague chapel and a great feast to follow. My mother had hankered after the French custom of putting the bride to bed, seeing that John was of France and she, herself, of Burgundy. But my father would have none of it, and that was a weight off my heart.

So John and I went to bed soberly. I was old enough to understand the nature of marriage; but surely marriage with John was different. For ten years we had played together, lain together in the hot sun and beneath the cool shade of trees. We were brother and sister; why should marriage alter that … for the present at least?

But when I was waiting in the great nuptial bed, I was not so sure. John stood there his too-thin body trembling beneath the bedgown, and there was a new look in his eye. I would not let myself be afraid of this new John.

‘All this playacting!’ I said. ‘Dear God, how tired I am—half-asleep already. Come to bed. Heaven be praised it’s wide enough for half-a-dozen.’

I saw how he flushed; but the old habit of obedience to my whims, held good. He came quiet into bed and lay brotherly next to me. The long day had been much for him; he was a delicate lad, and soon he was asleep. I knew perfectly well—even if my mother had not seen fit to remind me—my marriage duties as Child of Holland. But I was not yet ready. I was fourteen and just beginning to learn the nature of my own body. Had John been a stranger, excitement might have driven us together. Or, had I been given time, I should, I think, have come to love John the husband as dearly as I loved John the brother. But we were not given time.

The next day, seated in our chairs of State, we received the gifts of our nobles and churchmen and burghers. And then at last, our thanks being given, we were allowed to depart for Hainault, to spend what we Dutch call the white bread nights. And glad I was to leave the searching eye of my mother and her blunt questions. I had feared to the very last she would come with us.

In Hainault, among the childhood haunts where we had played as brother and sister, it was not hard to keep John from his husband’s rights. Soon, I would say, soon. He was not a lusty youth and soon he came no more to my room than to say Good-night. We were both of us young and time seemed to stretch endless before us.

And so the pattern of our new life was established before we returned to the Hague; and, for all the blessings of the church and the sharp tongue of my mother and the encouraging jests of our friends, there was no bedplay between us that first night or any other.

And so our pleasant life meandered on. John was gentle as ever. Sometimes it seemed to me that he was lower in spirit than he should be; but then, I told myself, he was delicate and easily tired. The truth is I was too young, and too selfish, to understand the strain I put upon him. Now that I understand the nature of the bond between men and women, I grieve—though it is all of twenty years ago—that I showed so little kindness.

I wore my new title Madam the Duchess of Touraine; but it meant little to me. I am Dutch in my ways—though there’s little more than a trickle of Dutch blood in me. For the rest I am Burgundian through my mother and Bavarian through my father. But I am Dutch in my thinking; and so I never thought of France, that it might one day be my home and I its Queen.

There was little to disturb these pleasant early months of my marriage except the usual quarrels between our noblemen which took my father away from home. Hooks and Cods the parties called themselves. Hooks and Cods. The very names are all-but forgotten now, though for years they spelled bloodshed and heartache; and to no one more than to me.

I must tell you how the quarrel began. My greatgrandfather was the Emperor—Louis of Bavaria; his wife was Margaret Countess of Holland from whom I inherit my lands. Many Dutch lords—Cods they called themselves because of the grey speckled livery they wore—hated the Bavarian blood of my family. But the Hooks—hooks to catch the Cods—stood loyally by my family.

For three generations now there had been continual quarrels between the two parties. My grandfather had managed to keep the Cods down; and so did his son after him. But it was a great annoy-ance to my father and a great worry, too. From the time I was a little child he worried about me, wondering what I—a woman—would do against the rebel lords when my own time came.

And then, suddenly, the pleasant order of my life broke; and everything was changed.

Louis, heir to the throne of France, died suddenly; and no true-born child to inherit the crown.

John was utterly cast-down. It was not so much affection—the brothers hardly knew each other. I doubt whether they had met since my betrothal ten years ago; and Louis had never been easy to love. It was an unwillingness, yes and a fear also, to step into the empty place. France was dark with bloodshed; not only the blood shed by Henry of England, but with that spilt by noble against noble; bloodshed and treachery. Treachery; there were ugly tales that Louis had been poisoned. And then, too, there was the mad King and the wanton Queen to reckon with, each incalculable; Louis might well have been poisoned between them! If John was afraid, it was no wonder.

In trying to rouse his spirits I had little time to think of myself and what Louis’ death was going to mean to me. But soon I began to notice deeper bows and curtseys and a greater running after me with compliments and gifts. Moreover my mother treated me with a new formal courtesy; but for all that I should not cease to be her obedient child. It was the prescribed respect paid to the future Queen of France—even though that Queen happened to be one’s own daughter. My mother rarely transgressed the rules of etiquette.

It was my beloved Beatrix who first spoke the words.

‘So now the Daughter of Holland becomes Madam the Dauphine. One day she will be a Queen!’

‘No!’ I cried out. ‘No! I don’t want to be a Queen. I don’t want to go into France. I’m afraid of the mad King—though I pity him, too. Oh he’s gentle enough when he’s well but when he’s sick—and the sickness comes without warning—then they take him away snarling and howling like an animal. And I’m still more afraid of the Queen; she’s in her right mind all the time; and it’s a wicked mind. If she didn’t like me she wouldn’t hesitate to put me out of the way; or if she found a better match for her son—then, Jacqueline goodnight!’

Beatrix put a finger to her lip; she went over and opened the door, looked into the next room and then slammed the door hard.

‘They say she poisoned Louis,’ I went on. ‘Louis, her own son! And, true or not, it shows the kind of woman she is! But most of all I’m afraid of my uncle of Burgundy. When he comes here, he’s a cloud over everything! He doesn’t come often—but often enough for me! But in Paris … in Paris …’ and I began to tremble.

She came over and put her arm about me. ‘Don’t let him trouble your heart. You forget your father.’

‘I could face it with my father; I can face anything with him. But he won’t be there. I don’t want to leave my father, Beatrix, I don’t want to leave him!’

She smiled at that; she was his daughter too.

‘I feel safe when he’s here.’ And I remembered the times he had stood between me and the worst of my mother’s tongue. ‘And I cannot, cannot leave him! Nor I cannot leave Holland where I was born and bred. And how shall I leave Hainault with its woods and its hills?’

And when she tried to comfort me with the woods and the hills of France I would not listen, crying out that I was a Hollander by birth and a Hainaulter by heart; and that I would not go into France to be among strangers that would not love me.

My mother, that ambitious Burgundian, could not understand my unwillingness to take possession of my fine new title. She would have bustled me into France then and there, but by father reminded her that we must wait until we were summoned; and that alone held her back.

Since my mother might not carry me into France until the summons came, she busied herself with new jewels for us both; and there were new gowns, new shoes, new gloves. My father, though he admired rich fashions in a woman, protested. I was but fourteen and growing fast. I should grow out of my clothes before all was ready. She did not, however, trouble herself to listen. She had the de Charolais love of display—though she could be mean enough where none could see.

And so, when the summons came at last to show the people of France their future King and Queen, everything was ready. And once again I was for France. And once again my father was not with us. He was in France trying to smooth out the quarrels between his brother-in-law of Burgundy and King Charles. And once again I longed for him, fearing his absence a bad omen. But my mother feared nothing—except that the spring winds might roughen my skin. We could not know, either of us, that soon my cheeks would be roughened with tears.

And so I come back full circle to where I began—back to Compiègne where I had been betrothed as a little child; and where now my young husband lay dead, and where my mother stood regarding me with annoyance, the black ribands in her hand.

II

Beatrix took the ribands; and even in this moment of grief, I saw my mother send her a look of dislike.

‘See that your lady has at least this much sign of grief about her,’ she said, severe; and, even while Beatrix was at her curtsey, slammed the door behind her. Beatrix came over and stood by me at the window. Did I, indeed, show no grief then for the loss of my dear companion? I had shed no tear; my heart was heavy as stone and as cold. And now, seeing the ribands black between the whiteness of her fingers, I was suddenly stabbed by my loss. She put her arms about me; but there was no comfort for me anywhere except in my father. For I was sick to the heart of Queen Isabeau’s wailing and I feared they would bring the mad King from Paris. At the thought I was shaken with fear. Father come quickly and take me home, home to my own Holland…

I watched Beatrix tying the ill-omened ribands. ‘When will my father come?’ I asked.

‘At any moment now. He will have heard that Monsieur the Dauphin is sick …’

‘But not dead, not dead!’ And even that word on my own lips could not bring the tears to my eyes, the tears I badly needed to shed.

‘John is dead.’ I nodded, driving the words home to my dull brain. ‘We came into France to show ourselves to the people. Well, John has shown himself for the last time.’

‘And you will never be Queen! Does that grieve you, sweetheart … a little?’

‘It’s the one good thing in all this heartbreak. I was not meant to be a queen. The smallest island of Friesland is dearer to me than the whole of France. And now, now I can go home!’ The longing in my voice shook my heart though it could not bring the tears. And I remembered my mother only this morning trying, no doubt, to comfort me—and her tongue all unused to gentleness. ‘It is not as though he were ever your husband,’ she said.

I think I must have shown some anger then; for I felt the colour burn in my cheeks and her own anger burst through; she could never endure being crossed or criticized. ‘You may well grieve! Had you done your woman’s part, your son would have sat upon the French throne. You slept with the man a full year and never a sign of a child. It’s hard to believe Isabeau’s son so backward! Even young Charles has got himself a bastard—and he but thirteen!’

‘I did love John,’ I told Beatrix now and it was as though I spoke not to her but to John lying unhearing in the next room. And then, since one must not lie in the face of the dead, added, ‘And yet I don’t know … Beatrix, I don’t know.’

‘You loved him,’ she said softly. ‘You loved him as a sister loves a dear brother.’

‘But he was my husband! And no desire! Tenderness, yes; but no stirring of desire. Am I like my mother, a niggard in love?’

‘You are all your father’s child,’ she said. ‘And a child, indeed! Fourteen. It was over-young for the marriage-bed.’

‘My mother was wed at fourteen. And Madam Queen Isabeau, too.’

‘The one’s a miser in love, the other’s a wanton.’ Her shrug dismissed them both. ‘You’re a more delicate breeder and must take your time. For all your fifteen years you’re a child yet! When the time comes you’ll give your heart and your soul; and, never fear, your body, too. You’ll get great joy from love; or great sorrow—and God alone knows which it will be. So don’t be in a hurry, child. And certainly this is no time to talk of love.’

She spread the loops of the ribbon and pinned the knot in the bosom of my light gown.

The gown looked more unsuitable than ever. The black knot set off the whiteness of my breasts. Isabeau herself, wantoning, could have done no better. I pulled it viciously from its place. Had I no better way of mourning John whom I should miss in every place? I should turn to show him this or that, but he would not be there; not in the garden where we had played, nor in church where we had prayed; nor yet in the bed where I had denied him.

‘Beatrix,’ I said, ‘I wish I had been kinder; before God I do wish it! I am stubborn and self-willed—so my mother says; and you, yourself, at times. I set my will against John often and often … and not only in the matter of our bed. And many a whipping he took for me. My heart breaks for it now.’

‘Little cause for heartbreak,’ she said. ‘Never think you bent his will to yours. Did you know him so little, Jacque, my dear? He did not bend his will to anyone—not to your father, not even to your mother; and certainly not to you. Weak his body was; but his spirit was strong. He gave you your way because it pleased him; it was his own will to please you always; yes and to take your whippings, too. And the things you wanted were harmless enough—to hunt rather than to sit indoors over the chessboard; to dance rather than to play upon the lute; to chatter rather than listen while he read. Had you wanted anything wrong, why then you would have seen. You would have seen a man!’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Yes. Of all Isabeau’s sons, he alone was pure, he alone was good … and I think he sits at God’s footstool. Pray that he will put in a good word for me.’

‘God judges for Himself, my heart.’

‘Then I am lost. Oh Beatrix, I do desire to be good; to be obedient and gentle and serviceable. But I am my mother’s child and my Burgundian blood is too strong. It defeats me; it defeats me, Beatrix. And so I must pray that John will whisper in God’s ear.’

And then I remembered that though his gentle spirit was certainly in Heaven, his body lay cold in the room beyond. And remembering the gentleness of his eyes, and the kindness of his mouth; and the hands and feet so quick in my service that were now still for ever, ‘I cannot bear it!’ I cried out all wild with my grief, ‘I cannot, cannot bear it!’

I swung round at the opening of the door.

It was my father. He knew. I saw it in his face as I ran into his arms.

‘So the rumours about Isabeau have started again,’ my mother said.

My father nodded. ‘They say she poisoned John as well as Louis.’

‘And I say so, too!’ And she bent her hawk’s eye upon my father.

‘They’re saying other things as well!’ He outstared her with a cold blue eye. ‘They’re saying your brother of Burgundy poisoned John because the boy wouldn’t jump to the whip, wouldn’t agree to sell France to the English. Your brother has a pact with the English … very secret.’ He turned to me. ‘I don’t think your uncle had a hand in John’s death, though he would have – had it suited him. As for Madam Isabeau, her reputation isn’t sweet. Yet you saw her; cheeks raw and chapped with tears. Were they true tears, do you think? Is she a woman, for all her whoring, to poison her own sons?’

I said, ‘Louis was weak enough to snuff himself out if he breathed too hard; why should she burden her conscience with him? And John.’ I stopped, remembering my mother-in-law wailing and her voice all roughened with tears. They took him from me ten years ago and he but seven years old. Ten long years. And I did not set eyes on him again until I saw him in this same Compiègne … and he was dying. Sweet Christ save us such a death!

‘No,’ I said, ‘I don’t believe it.’

‘Then you show a sound judgment. For the truth is John died of a discharge in the ear.’

I nodded. And I remembered now, John sitting in the charette and cupping his ear with his hand. He had looked pale and heavy but he had not complained; he never complained.

‘I am glad you show good judgment,’ my father said. ‘God knows you’ll need it; and perhaps sooner than you think!

There was something about him, a sadness strange to his gay spirit, so that even my mother turned a startled eye. ‘What’s on your mind?’ she asked and her voice had lost some of its sharpness.

‘Nothing,’ he said and shook his head. ‘Nothing.’

We were home again and I missed John at every turn. I could settle to nothing. My mother, impatient at seeing me downcast would rally me. ‘Do you miss the French crown? We’ll find you another as pretty, never fear!’ I would do my best to smile, she had no love of a whey face; and the sting of her tongue could quickly turn white to red. So I never told her that I had dreaded nothing more than the French crown, the French court—the mad King, the bad Queen and my dark uncle of Burgundy. For the crown of France was gone and all its terrors with it. I was the Daughter of Holland. I asked nothing better than to rule when my time came—let it be long in coming!—in peace and in justice and in prosperity. John was a heavy price to pay for freedom; the French crown a light one.

These days there was a tenderness between my father and me; a tenderness on his side the deeper because it was to be so short—though I did not know that then; a tenderness on mine because he looked so ill. He would walk a few steps and then stop, his face pale and shining with sweat; and then he would force himself on with dragging feet.

I knew he was sick; but I never believed that he was going to die—a man in the flower of his handsome manhood. Of course he would get well again! He must get well again! God would not take my father from me, too.

Nor would my mother admit things were bad. Once she came upon me, weeping; and when, I stammered out that it grieved me to see him in pain, she cried out that he was well enough; and would recover soon. Girls with too much time on their hands were apt to grow fanciful! And I did not see that her sharpness covered her own fear.

‘We must find you a husband,’ she ended. And now it was my turn to cry out. It was too soon, too soon! But she pooh-poohed my nonsense. ‘Daughter of Holland—certainly you must marry again; and quickly. Besides, it’s right for every woman to marry as soon as may be—unless she choose to bury herself alive in a nunnery. And that, I fancy, would not suit you at all!’

‘I must marry, I don’t question it,’ I told her at once. ‘But not yet; not just yet.’

‘Fruit that’s over-ripe rots quickly,’ she said. ‘There’s no market for it.’

I said no more and so we left it. I must marry again; but I would not shame John’s memory with a hasty marriage: On that I was determined. My mother must leave the matter for the present. I would ask my father to command it.

I remember I was standing by a window at the Hague Palace watching the birds flying and crying over the lake when I told him what my mother had said.

For a while he did not speak but stared out over the water as though the swooping and darting of birds were his sole concern. He turned at last and said slowly, ‘God forgive me but I must speak … while there is time. Don’t trust your mother, Jacque. She’s a de Charolais. To advance the honour of her house—her own house—she’d be without pity, without faith. One day you must stand against her. Your mother and your uncle of Burgundy! You must stand against them both … and it may be, alone.’

I should have known then how near to death he was, but his meaning was lost in surprise that he counselled me to defy my mother, I that had been trained to immediate obedience.

‘This talk of marriage is no surprise,’ he said. ‘They’ve been plotting together—your mother and her brother—ever since John died.’

‘It’s too soon,’ I told him as I had told her. ‘Too soon.’

‘Princes cannot stand upon niceness,’ he said gently. ‘For the sake of this country, its peace—its very existence as a free people—you must marry again and soon.’ He took my hand. ‘Those two have chosen your husband; and it is not the one I have chosen. If you wait too long I may not be here to speak in the matter.’

And now he had spoken so plainly of his death my heart turned over. He was my father; he had always been there. What should I do lacking him?

‘The groom they have chosen is your cousin of Brabant,’ he said.

‘No!’ I cried out at once. ‘He’s too young.’

‘Too young, too feeble-mind and body. A bad marriage; and you must not make it. You must not make it, Jacque. Marriage must secure the succession to you and to your children. The Brabant marriage will do neither. Brabant is under the thumb of Burgundy; and it is Burgundy that will rule, not you, Jacque, not you. Dutch necks beneath the Burgundian heel! It would haunt me—heaven or hell.

‘As for children, I doubt Brabant will give you an heir—he’s rotten stock. And he’ll never make old bones! He’s riddled with the sickness that comes from loose living. He’ll die long before you, as far as man can see; and he’ll hand you and your inheritance over to Burgundy. If you take Brabant then you are lost; and your inheritance is lost, all, all lost.’

‘I would not marry Brabant if he were the last man in Christendom; and you may set your mind at rest. But if I must marry—who shall it be? Who?’

He said slow and doubtful, ‘There’s been an offer from England. King Henry offers his brother.’

The King of England’s brother! There was a marriage, indeed! And I remembered a young man who had come to our court, a debonair young man, bowing over the hand of a solemn child as though she were a woman and a beauty.

‘Gloucester!’ And I hardly knew I had said the name.

‘Not Gloucester. Not Gloucester,’ he said at once. ‘The Brabant marriage would be bad; but marriage with Gloucester, worse. Oh he’s charming; clever, too. But there’s no principle of good in him. He’d split this land in pieces like an orange and suck each piece dry. Not Gloucester. Bedford.’

‘No!’ I said at once. I had heard of Bedford—a great fighting-man, hard hand, hard head, hard heart.

‘He’s a good man; but not for you, perhaps … not for you. No foreign marriage—be the man never so true—would hold this land together. Jacque, my child, I have been thinking and thinking long. You must take one of our own nobles.’

One of our own nobles! A come-down, indeed, from the royal house of England.

I said quickly, ‘That would not suit my mother at all.’

He looked down into my face. ‘Nor you neither, it seems—not so glorious as the English marriage, I admit. But it would suit Holland very well. It would be a good marriage, a right marriage. Think, child! A strong man, respected alike by Hooks and Cods. He would keep the land in peace for you and for your children.’

I could not speak for disappointment. At last I said, slow and grudging, ‘And which gentleman have you in mind?’

He looked at me very steady. ‘Van Borselen,’ he said.

The Zealander, more bitter than most against our Bavarian blood! Van Borselen, leader of the Cods, a hard man; a most harsh pride. Van Borselen! I could not believe it.

‘You would give me into the hand of the Cods?’

‘I would join your hands,’ he said, ‘to keep the land in peace.’

I said bitter, ‘And if van Borselen refuse? Do I offer myself to his brother? Or to van Arkels? Or to whichever Cod will take me? I am a woman—do you forget it?’

‘You are a prince,’ he said. ‘And I think you forget it. For what is a queen, even, but a piece to move here and there as best suits the game. And if the queen is not played shrewdly then she is lost—and all is lost. Think of it, Jacque; but do not think too long. Time passes … it passes.’

III

My father was a very sick man; even my mother could no longer deny it; now he could not endure the coming and the going at the Hague, nor yet the bustle of the smaller court at le Quesnoy. He longed for Bouchain and the quiet house he loved.

I shall never forget that journey. He tried to ride; but soon he let them carry him to the charette. He lay back on the cushions, his teeth clenched so that there was blood upon his lips; and, as the carriage jolted him this way and that, his face that had been white, took on a blue look and glazed.

At Bouchain he went straight to bed and his surgeon was summoned. I was waiting in his dressing-room when I saw them take the bloody cloths away. It was late evening and a blackbird singing, and the hawthorns shaking their scent into the Maytime air, when my mother came out of the bedchamber.

‘That old bite!’ she said, brisk; but her eyes were troubled. ‘They have lanced the swelling to let out the poison, and soon he will be well again.’

‘Please God!’ I said. If only my father would get well, I would build a chapel here at Bouchain. And I would furnish it with gold and silver; and I would endow it … but one must not try to buy God. My confessor had told me that when I was a little child, running to God all eager with my requests and my offerings. Then dear God, I promised, I will build You a chapel whether my father gets well or not … but let him get well!

When I saw him next day I knew he was not going to get well.

‘Come, never look so sad,’ he told me smiling, and all the time his teeth clenched against the pain. ‘A bite … a little bite … long ago.’ And there was wonder in his voice.

The old bite. Those that had called my betrothal ill omened had been right. My young husband was dead; and now my father was dying of the mishap that had befallen him riding thither.

The next day I did not see him at all; but there was a constant procession, not only surgeons and priests, but nobles and councillors summoned to his bed. I knew then that all hope was hopeless.

‘My father left the Hague for peace,’ I told my mother all angry with my grief. ‘Why do they trouble him with all the coming and going in his bedchamber?’

She hesitated; she said, and her voice had lost its sharpness, ‘He is calling upon his nobles and his burghers to give their loyalty to you.’

‘Loyalty? I am the Daughter of Holland! Who can withhold it?’ ‘Those that are anxious for your shoes. Your father’s brother for one. He’s had a greedy eye on your inheritance this long while.’

‘But he’s a priest … a bishop!’

‘Bishop-elect only. And itches to change a mitre for a crown.’

‘I am Daughter of Holland,’ I said again, ‘I am my father’s heir.’

‘It’s not as simple as that,’ she said. ‘Would God it were! Your father holds his countships under the Emperor; and the Emperor may count it a male fief. In that case it is not you that would inherit … but your father’s brother.’

That, I, Daughter of Holland, might be set aside was a new thought; and a frightening one. With his death, I lost, it would seem, not only a beloved father but maybe my inheritance as well. I had been brought up from babyhood as my father’s heir; my whole training, my whole mind, had been directed to that end. To lose that inheritance would be like losing a hand or a foot—my whole life maimed.

I had no more tears to shed; stony-eyed, this early summer’s day, I watched the stream of men passing in and out of the sick room. Some I knew well; others not at all.

First and foremost, my father’s brother of whom my mother had spoken—John of Bavaria, bishop-elect of Liége, with his dark, cruel face. My father had summoned him to swear protection to me, his young niece and hereditary prince. Oh he would swear and swear again, but would he keep that promise? I looked into his face and had my answer.

I saw him as he came from the sick room. His cold eye picked me out where I stood in the shadow of an alcove. He came over and bowed over my hand and smiled as if to comfort me. But his smile frightened me more than his scowl—a dog’s grin. Hard to believe the same loins had sired this man and my father.

A little later my mother’s brother, my uncle of Burgundy, strode in. I had not even known he was expected; my mother must have sent for him days ago; yes, even while she was making little of my father’s sickness.

I stood up as he came out but he gave me neither word nor look. Perhaps he did not see me, for his lips smiled a little, which was not fitting, coming as he did from a dying man.

Between my Bavarian uncle whom men called the Pitiless and my Burgundian uncle whom they called the Fearless, I was likely to fare ill. Blessed St James intercede for me … I found myself praying to my patron saint that my father might even now be spared; and this time I prayed for myself, too.

These bitter days I could not bring myself to leave the anteroom. If my father had strength to see all these strangers, surely he must send for me, his child!

Half-hidden in my corner I would watch them go into the room; and through the half-open door I could see my father’s face as the chamberlain spoke their names.

First came the great family of van Brederodes that are sprung from the same stock as myself, loyal to the core—Gysbrecht, the fighting bishop of Utrecht that had both christened and married me, Reynolde Lord of Vianen, and between them William Lord of Brederode head of their house, that grim fighting-man and my father’s dear comrade in arms. I saw my father’s sick face lighten as he went in. Then followed Renald Duke of Juilliers, a most turbulent man, with his kinsmen the great van Arkels, father and son; and, on their heels, the Lord of Egmont. Rich men these, of ancient family; men of weight with burgher and with peer. I prayed St James that their hearts would turn to me; but I saw the sorrow in my father’s face as they went out and had no hope of them. But my heart lifted a little when Everhard of Hoogtwoude and Lewis of Flushing went in together and I saw the tenderness in my father’s face. His own sons, these; begotten when the blood was hot and his stamp was upon them both. Fine men, upright and true. My brothers—and I thanked God for them.

And so the days wore on; and the long procession came and went. Didier van der Merwen came with the old Lord of Sevenbergen, and Arnold of Eienburch and many another I had known from childhood, good Hook nobles all. But my heart knew its enemies too. William Lord of Ysselstein and William of Lochorst, and other Cods with them; and all of them whispering together … and nothing good to me.

It was the evening that my father died and summer dusk darkening the room when two men came in together; tall men with a cold, grave air—brothers it was well-seen. That they were great lords was not to be doubted; there was power about them and pride. Many of our nobles wear something of this look; but in these it was deepened, as though their very being was distilled from pride. Who they might be I did not know; that they were not friends, was certain. They did not carry themselves like friends come to bid their dying lord Farewell.

If there was great pride in them, there was, I fancied, great integrity, too. I half-put out a hand to them as they went by; but they did not see me hidden in my place.

If I had gone forward, shown them my tears and my need, would my life have been different? Who can say? They were hard men and proud; and they were set against my father and his house … and I stayed in my place and I let them go by.

I heard the low murmur of voices in the next room; my father was trying to persuade them to friendship. But it was all useless. I heard the clear No!

Who were they, these proud men, these men of power? Outside the anteroom a page lounged, wearing a livery I did not know.

‘Who are those two that went in just now?’ I asked.

He looked at me in contempt; and that was not surprising. If I did not know his master, he did not know me, unkempt as I was and stained with my tears, my plain gown crumpled where I had fallen asleep in my chair.

He said, insolent, ‘It is not to be expected you should know them. They are no friends to this house. The taller is my master the Lord Frank van Borselen, Seigneur of Zealand, and the other, his brother Floris.’

Lord Frank van Borselen. The man my father desired for my husband—the cold, proud man. I felt my heart shrink within me. As a husband—no, no! But as a friend—? And I remembered the way he had carried himself, an air, it seemed to me of triumph, that his enemy lay dying and he, himself proud and strong. And I remembered the sharp No. Neither husband nor friend here! Living or dying, neither my father nor I would ever win his favour.

‘You may well stare!’ And the boy was contemptuous as though he spat. ‘My lords come not in friendship—though the Bavarian seeks to decoy them. And the decoy?’ There was a lasciviousness about him. ‘A hen. A plump white hen for my lord Frank. Well that cock’s particular. He’ll not step this hen and you may tell your mistress so; and, moreover …’

The words died in his throat. He stood staring, mouth slack, high colour faded to a sickly green.

‘You’ll end your days without a tongue if you put it to such foul use,’ Frank van Borselen said. It was a low voice, no trace of anger in it; yet frightening by its very quiet.

‘This is a house of mourning—or soon will be. You shame me with your loose talk. Your pardon, mistress,’ but his eyes did not see me. I might have been any serving woman, save that our wenches are neat and fresh. ‘It is a low fellow and has much to learn—if he have the wit!’

The brothers strode off without a backward look and left me standing there.

I stood looking after them. And now my hand was held out towards them. Enemies to me and mine. But there was a justice in them and a courtesy and I coveted them for friends. But it was too late. They neither turned nor slackened and I was left standing with my empty hand.

He’ll not step this hen, this plump white hen …

My hand fell to my side. I knew now what the boy meant.

Beatrix coming in to call me for supper found me crouched in the dark. She put out a hand; her fingers lifted my chin, felt the wetness of my face. ‘Jacque, my dear, my darling! This is a time of sorrow for you … and for us all!’

I turned away my face and she said no more; only her hand stroked the tangle of my hair.

I said, ‘Do you know the tale of the cock and the hen, the plump white hen?’

‘No,’ she said, ‘is it a good tale?’ and she was puzzled. ‘It depends if you’re cock or hen.’

She said, ‘I was never good at riddles. Come, Jacque, speak plain.’

‘A barnyard jest—’ and I began to tremble.

She said, ‘When we’re overthrown with grief so very little hurts us! You had best tell me, Jacque.’

So then I told her, sitting there in the dark and she stroking my hair.

‘You are not clever, Jacque,’ she said. ‘This van Borselen refused not you, but your father. Why, he never set eyes on you in his life! Come, sweetheart, do a few words from a foulmouthed boy distress you? The Lord of Borselen showed how all clean men must think, friend or foe! And, if you were yourself, you’d see that plainly. Your father thinks of you; your happiness, your safety, your greatest good. And that’s the good of the country; the two go together. Van Borselen leads the Cods. Gain him—and you gain the Cods. Your father sought to make an enemy into a friend. Is that so shameful?’

‘It is shameful to be offered to a man and be refused.’

‘Nonsense,’ she said, crisp. ‘Princes are bartered every day; they are the common coin of affairs. If shame there is, it isn’t yours. It rests with the man that values enmity above his country’s peace, that grows fat on bloodshed …

‘He’s a lean man,’ I said. ‘Very cold and proud.’

‘Would you have taken him if he had said Yes?’

‘As a friend—with all my heart! As a husband—I should have obeyed my father. But I should have wished myself dead first.’

‘You cannot have it both ways,’ she said. ‘And this is the best way.’

I nodded. ‘He was my father’s enemy and now he is mine. It is good to know enemy from friend.’

I was eating my supper, and every mouthful fit to choke me, when my father’s summons came.

He lay white in the warm glow of the cressets; and their flickering light moved upon the hollows of his cheek. Already he wore a remote, cold look.

The physician stood up and came to me where I stood in the doorway. ‘You must let him say what he will, my lady. Do not try to stop him. Until he has finished he will not allow himself to die … and he is very tired. His mind is clear and he has saved himself for this purpose. Every now and then you must moisten his lips.’ He nodded towards a cup with a feather lying across it. ‘I shall be in the next room if you need me.’

He went out and I crossed over and knelt by the bed.

For a while my father said nothing, only he searched my face with his eyes—eyes that had been so gay and were dark now with the shadow of death. They clung to my face as though they could never be done looking.

‘Child,’ he said at last, ‘little Jacque.’ His voice was faint but the words came clear. ‘Friends are gathering. Enemies … enemies, too. The Emperor …’ He shook his doubtful head. ‘Your uncles …’ he shrugged wearily—a shadow of that quick shrug of his. ‘Poor child! My brother has promised; but …’ he shook his head again from side to side. ‘Watch the bishop. Once we played together you and I … but it’s a game no longer. Watch the bishop, watch my brother, Jacque. And watch the knight—the knight that doesn’t jump straight; that’s your uncle of Burgundy. Never trust him. Oh he’ll promise, promise—but never trust him. Our lands march too close with his … too close …’

For a while he said no more but lay there, his face twitching with pain; at last he spoke again. ‘Your mother and her brother … stand against them both … you must. Hard … hard … but you must do it!’

His eyelids fluttered down and I moistened his lips with the wine. At last he spoke again.

‘You cannot stand alone. Listen … do you listen? You must marry as I said … you … must … marry…’

I took in my breath knowing the name that must come.

‘Van Borselen,’ he said and his eyes were fixed on me. ‘He has refused,’ I said.

‘Ask … again. You must ask.’

I said nothing. Offer myself? Be refused again?

‘Hard,’ he said. ‘But not too hard … nothing too hard … for the people. Your duty, Jacque … your duty!’ And his eyes besought me.

‘England?’ I entreated him. ‘What of England?’

He shook a fretful head. ‘No foreign hand … even the just hand. I know … I know …’ He was murmuring now, no longer clear. ‘I fought … for peace … all my life. But—’ he lifted his own hand, looked at it, let it fall again. ‘No foreign hand …’ He lay there whispering to himself.

Suddenly his voice came clear—for the last time clear. ‘Ask, ask van Borselen,’ and fixed me with his darkening eyes.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Yes.’ And then, ‘If he refuse me?’

The lids had fallen. I knelt down and whispered urgently in his ear, ‘If he refuses me—what then?’

But there was no answer. He had my promise; it was enough.

It was very late now but I could not go to bed. My heart was full of grief and burdened with its troubles. I knelt beseeching heaven for the passing of my father’s soul.

Sunlight was full in the room when Beatrix’ hand upon my shoulder awakened me.

‘You should come now,’ she said, very gentle; her eyes were sunk deep into their sockets with grief—she was his daughter, too.

My father lay flat upon his back, the nose sharpened in his face and the dreadful sound of his breathing rattled like chains—chains he would soon cast off. My mother knelt by his side; he did not know her and he did not know me. His fingers were plucking; and between the rattle of his breathing I caught his muttering … crooked knight … crooked bishop … crooked … crooked. His hand moved dimly as though to take a piece from the board—and it was as though he took my heart in his hand.

The hand dropped.

‘Bouchain …’ he muttered … ‘Bouch … ain …’ And all the time the dreadful chain rattled in his chest.

I did not know what he meant but my mother did. She bent over him in the great bed—the bed she had once shared with him. ‘Yes,’ she said; and it was a voice I had never heard in her before … or since; very gentle. ‘At Bouchain. I promise.’ And she bent and kissed his cold mouth.