12,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

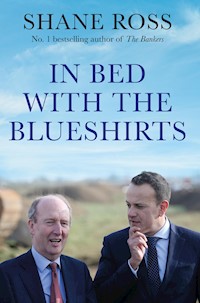

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

The definitive inside account of the 2016-20 coalition government. Cabinet minister Shane Ross reveals the bitter internal battles fought with the old Blueshirts, the crises when the coalition came close to collapse and the sometimes fraught personal relationships between the fifteen figures who made up the last government. He recounts how a group of Independents risked everything to form a government that was expected to last for only months but which ran for more than four years, under two Taoisigh with utterly different styles. With great humour and charm, Ross unveils the skulduggery, the secret deals, the drama of how Irish football was rescued and Olympic chief Pat Hickey toppled, showing us what really happens behind the closed doors of Ireland's government.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

IN BEDWITH THEBLUESHIRTS

ALSO BY SHANE ROSS

The Untouchables (with Nick Webb)

Wasters (with Nick Webb)

The Bankers

First published in Great Britain and Ireland in 2020 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Shane Ross, 2020

The moral right of Shane Ross to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Trade paperback ISBN 978 1 83895 291 4

E-Book ISBN 978 1 83895 292 1

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Printed in Great Britain

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Prologue

Chapter 1: A Big Idea Is Born

Chapter 2: The Blueshirts Play Hardball

Chapter 3: A Cabinet at War

Chapter 4: Pat Hickey’s Olympic Downfall

Chapter 5: Gaffes Galore

Chapter 6: Pork Barrel Politics

Chapter 7: Drink Drivers Divide the Dáil

Chapter 8: Judges Defend Four Courts Fortress

Chapter 9: Mandarins Rule, OK?

Chapter 10: Irish Football Pulls Back from the Brink

Chapter 11: The Covid Cabinet: A Big Win for Leo

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Index

The book is dedicated to all who have tragically died on Irish roads. Especially let us thank the victims’ groups who have worked so selflessly to ensure that others do not suffer the unspeakable agonies endured by themselves. There is no nobler action than theirs. Their part in supporting the Drink Driving Bill has undoubtedly saved lives. It is sadly too late for members of victims’ groups like the Irish Road Victims’ Association (IRVA) and Promoting Awareness, Responsibility and Care (PARC) who have lost loved ones, but many people would not be alive today without their endurance and determination.

Prologue

IT LOOKED LIKE the beginning of the end. Enda Kenny was in full flight at the cabinet table. The Constitution held tightly in his hand, the Taoiseach was waving it in anger at Finian McGrath and at me. He was obviously at the end of his tether. We were only six months into government. Everyone knew we could not go on like this. Nearly every week there was a spat, a fudge and a bad taste in the aftermath.

On Tuesday, 22 November 2016 the issue was neutrality. The cabinet had already seen showdowns on abortion, on the Apple tax judgement and on a Fine Gael nominee to the board of the European Investment Bank. On most Tuesday mornings there was a war of attrition. The media waited expectantly for a good leak about the latest row. They were rarely disappointed.

Sinn Féin had put down a mischievous Dáil motion calling for neutrality to be enshrined in the Constitution. Finian, John Halligan and I had voted enthusiastically for an identical measure a few months earlier, when in opposition. It was due to be debated within forty-eight hours. If we opposed it now, we were hypocrites. If we supported it, the government was split. And probably reduced to the status of a divided rabble with a short life.

It was a heated debate, not defused in any way by the interventions of the excitable Minister for Foreign Affairs, Charlie Flanagan, sitting opposite me. Every cabinet minister paid lip service to Ireland’s military neutrality, although many Blueshirts had never been more than token believers. I looked around at my colleagues, silently thinking that collectively they would make a NATO gathering look like a social democratic think tank.

I glanced down the table at Leo Varadkar and Simon Coveney, destined to be locked in a leadership battle to succeed Kenny in less than six months. Leo, already seen as the likely winner, would surely never relish a head-to-head weekly battle on issues like neutrality? We didn’t have to wait long to find out.

As the minority group in government, we in the Independent Alliance had a clear position: there was no commitment to any view on neutrality in the Programme for Government. We expected a free vote. A few months earlier, we had rubbed the Fine Gael noses in it, taking a free vote on abortion in the face of fierce opposition from them, our partners in government. No political earthquake followed. Neutrality, a matter of conscience and principle, was in a similar category.

Kenny was not going to allow a repeat. He was adamant. He lifted the Constitution in the air, a copy of which lay permanently on the table in front of Martin Fraser, the influential cabinet secretary, seated beside him. There was silence around a hushed table.

Enda raised his voice in response to our demand for a free vote: ‘Bunreacht na hÉireann,’ he declared, brandishing the sacred book, ‘trumps the Programme for Government.’ He demanded total cabinet solidarity. The Constitution requires the cabinet to speak with una voce. So did all true Blueshirts.

It was left to Tánaiste Frances Fitzgerald and elder statesman Michael Noonan to broker a compromise with us. We eventually agreed wording for an amendment, with everyone around the table reaffirming their commitment to military neutrality.

News of the row leaked, as it always did. The media had another field day. Two days later Sinn Féin took lumps out of John Halligan, Finian McGrath and me in the Dáil chamber. Finian and I voted with the Blueshirts. John Halligan was away. Martin Kenny and other Sinn Féin deputies taunted us about our deafening silence.

The great experiment was faltering.

1

A Big Idea Is Born

FINE GAEL NORMALLY eat their young. Only amateur political innocents have not learned a basic lesson of history: those who bounce into bed with the Blueshirts die a painful death. Independents with blind ambition were long ago warned about this fatal political certainty. Nobody has ever survived as much as a flirtation with Fine Gael. Look at Labour today or even the Democratic Left. Back in 1951, Clann na Poblachta disintegrated after supping with the same devil. Oblivion beckons to those who fly too close to Fine Gael.

Two days after Christmas in 2014, I set out on a mission. I was in search of an answer to a brewing political question. Independents were on a roll. So, was there an opening for independents to form a coherent political force? I spent a freezing winter week touring Ireland to test the temperature. I met independent councillors from Dublin, Wexford, Cork, Galway and Sligo. And others on the road back to Dublin. In a few days — over the 2014/15 new year — thirty councillors offered their views face to face. Nearly all favoured a new departure where independents would co-operate nationally. And formally.

Some were rural, others urban. Some pro-choice, others pro-life. A number came from the Fianna Fáil gene pool, others had long-term associations with Fine Gael, or were disillusioned Labour, dejected Greens or even closet Sinn Féin supporters. Many had started political life as single-issue candidates. Independents were (and are) a mixed bag with various agendas. Detractors rubbished them as a motley crew.

It was the first of many similar journeys I undertook over the next twelve months. It led to the doors of current household names like Boxer Moran, Michael Collins, Seán Canney and Paul Gogarty, all independent councillors at the time.

Parallel to that, at national level, similar tentative moves were being made by sitting independent TDs in Leinster House. After the 2011 general election, a ‘technical’ group of sixteen independents had been formed to ensure that they had speaking rights in the Dáil. It included such personalities as the delightful left-winger Joe Higgins and the sometimes less delightful right-winger Mattie McGrath. We shared a few parliamentary facilities, but policy differences made political unity or consensus impossible.

Many independents shared a corridor in Agriculture House, attached to Leinster House. Sometimes that merely exacerbated tensions. Deputies Mattie McGrath’s and Catherine Murphy’s offices were opposite each other. The two deputies were barely on speaking terms. Mattie, a devout pro-life Catholic, posted a sketch of Pope Francis outside his office. Catherine, a passionate pro-choice agnostic, could not avoid passing it every time she entered or exited her room. No one believed that Mattie was unaware of the daily effect the picture of His Holiness would have on Catherine’s blood pressure. Catherine, in turn, had pinned on her door a picture of the victory celebration for the referendum on marriage equality in Dublin Castle. Mattie could not miss it, but it was certain to cause the already excitable Tipperary TD one of his familiar apoplectic fits.

Yet, within that group, Catherine Murphy and a few others saw opportunities for political reform. Herself a veteran of several left-wing parties, she found common ground with others, but not with Higgins’ far left or with Richard Boyd Barrett’s brand of socialism. Nor with Clare Daly, a staunch ally of Higgins before a spat threw her into the arms of another colourful independent TD, the ultra-maverick Mick Wallace. The independents had their own Bonnie and Clyde wing.

Catherine Murphy often spoke to several like-minded TDs, seeking a collective, more cohesive political muscle, based on a common radical zeal. In the middle ground of this disparate group stood more flexible, pragmatic politicians, including her former Workers’ Party comrade — then independent TD — John Halligan, newly elected TD Stephen Donnelly (known to some as Harry Potter because of his uncanny physical resemblance to J.K. Rowling’s hero), left-wing disabilities champion Finian McGrath, Michael Fitzmaurice from Roscommon, Tom Fleming from Kerry and me. None of us, so it seemed at the time, wanted to stay in opposition for ever.

Talks between Murphy, Donnelly, McGrath, Halligan and me had been progressing sporadically. Attempts at sorting policy differences were slow. Murphy and Donnelly wanted a political party structure with the accompanying rules and discipline; I and others wanted a looser alliance that gave independent members the right to free votes according to their individual consciences.

Free votes on matters of conscience had already propelled another player into the crowded independent/new party space. Lucinda Creighton, a former Fine Gael minister, had been ruthlessly expelled from the party in July 2013 as an objector, on the grounds of conscience, to Enda Kenny’s abortion legislation. She had been in exploratory talks with both Donnelly and me, but if the difficulties of whether to form a party or an alliance proved a fundamental obstacle, the problem of three runaway egos uniting behind one leader was thought to have been insuperable. The Ross ego, once described by journalist Mark Paul as ‘the size of Croke Park’, may have just pipped Donnelly’s and Creighton’s, but they ran me close.

Fine Gael and Labour, with an unassailable majority in the Dáil, watched contentedly. Opposite them in the chamber slumped a discredited Fianna Fáil. Alongside Fianna Fáil sat a group of sometimes articulate independents already splitting into warring factions. Sinn Féin was not then the force it is today.

Under that coalition, legislation was frequently guillotined. Oireachtas committees were controlled by Labour-Fine Gael majorities. The Dáil and the Seanad were rubber stamps. Unpopular legislation, arguably necessary because of the perilous state of the nation’s finances, was rammed through both houses. Fundamental changes, like the introduction of property and water taxes, were rushed through Ireland’s parliament with indecent haste. Fertile ground was being prepared for left-wingers and independents to foment discontent. Even the Greens, wiped out by their craven support for the previous Fianna Fáil government, managed to plug into the growing unrest. Huge marches in the streets against water charges spooked the Fine Gael-Labour regime. While the opposition was able to unite against the unpopular austerity measures, it split on a multitude of fronts when it came to agreeing a common platform. It proved impossible.

Opposition was an easy place for independent mavericks. It was not difficult to find reasons to oppose austerity, even if the various independents offered different reasons for doing so. Solutions, suggestions, proposals for common future positions prompted immediate splits.

Nevertheless, in early 2015 the political soil was perfectly prepared for the green shoots of an independents’ spring. The record success of independents in the summer 2014 local elections proved that their earlier surge in the 2011 general election had been no flash in the pan. Later in 2014, independent Michael Fitzmaurice had pulled off a surprise coup when he succeeded Luke ‘Ming’ Flanagan by winning the Roscommon-Galway by-election. Flushed with victory, Deputy Fitzmaurice took only a few weeks to declare the need for a new political force or party. Presumably with himself at the helm. He told TheJournal.ie that he had spoken to twenty-five to thirty like-minded people. Another mega-ego had entered an already crowded arena.

Suddenly 2015 looked likely to be the year of the political adventurer. It was. No sooner had I arrived back from my countrywide tour of independents than Lucinda Creighton broke cover. On 2 January 2015 the worst-kept secret in Irish politics was revealed. Lucinda announced that she would have something else to announce in due course. She would be launching a new political party. But not until March. She held a press conference with consumer champion Eddie Hobbs and an Offaly councillor, John Leahy. Remarkably, no other TDs were sitting on the platform.

Within less than a week, on 6 January, both Fitzmaurice and I appeared on RTE’s Prime Time to announce that we were joining forces to form an alliance of independents. According to the programme, others to have expressed their enthusiasm for such an idea (but not for either Fitzmaurice or me) included Deputies Denis Naughten, Noel Grealish, Stephen Donnelly, Tom Fleming, Mattie McGrath, Finian McGrath and John Halligan. Prime Time headed the programme with Fitzmaurice speaking of me: ‘He seems to be a very reasonable guy in any talking I’ve done with him and yes, I think we can work something together.’

That was the night the Independent Alliance was born. And it was almost stillborn. Not all the dots had been joined up when Prime Time jumped the gun. The independents identified as possible allies had been talking in silos. They had never met in a room together with a common purpose.

While Fitzmaurice had been speaking separately to rural TDs and councillors, Finian McGrath, John Halligan and I had been in exploratory conversations for over a year. I had been in a separate dialogue with Stephen Donnelly for several months. There had been little contact between Donnelly, Fitzmaurice and Halligan. Rivalries erupted within twenty-four hours of the RTÉ programme. Several of Prime Time’s supporters of an alliance of independents, in theory, ran for cover when confronted by the reality of the names of their prospective allies.

Within days of the programme, three of the independents — Donnelly, Naughten and Grealish — met in secret in Donnelly’s Dáil office and resolved to torpedo the Independent Alliance project at birth. Naughten was always a non-runner for our group because he and Fitzmaurice were deadly rivals in the same Roscommon constituency. In any case, Naughten had hedged his bets on Prime Time, carefully approving the idea only ‘in principle’. Donnelly was unwilling to accept Fitzmaurice because he believed the Roscommon man would be a political obstacle to his ambition of linking up with left-wingers Catherine Murphy and Róisín Shortall. At the time, Donnelly was fond of proclaiming his social democratic convictions. Many found his protests unconvincing because he hailed from a career in McKinsey & Company management consultants, hardly a bedrock of radical economic thinking.

Grealish and Naughten went to ground. Donnelly bolted. He privately explained to me that Fitzmaurice lacked the quality of the sort of TD he wanted to include in his gang. He felt that Naughten outstripped Fitzmaurice in polish and ability by a country mile. Six months later, in July 2015, after tortuous weeks of talking, he fell happily into the more comfortable, urban and conventional hands of Catherine Murphy and Róisín Shortall when the trio launched the Social Democrats.

Donnelly’s defection was a blow, but five TDs held firm. Tom Fleming, Michael Fitzmaurice, John Halligan, Finian McGrath and I decided to embark on a great experiment. We were seeking to be part of an independent group in the next government.

The fault lines were drawn. Five independent TDs wanted an independent group without a whip. Donnelly was a cut above the rest of us, in search of a cerebral, social democratic home. Lucinda Creighton was hell-bent on a right of centre anti-abortion party. Catherine Murphy and Róisín Shortall were debating a new social democratic initiative. Other rural TDs — Denis Naughten, Mattie McGrath, Noel Grealish, Michael Lowry and Michael Healy-Rae — decided to remain aloof in their solo positions, detached from the rapidly forming new groups.

It was time for the talking to stop. A general election was expected in autumn 2015. The new Independent Alliance needed candidates to sign up. The long march to shape an effective army out of a group of independent councillors, unused to political discipline, had begun.

The five deputies and our new recruit, Senator Gerard Craughwell, met in my office every week. We needed money, so contributed €1,000 each to start the operation. Over the following two months, we met dozens of sometimes curious observers, sometimes eager disciples. As an introduction to test the waters, independents from around Ireland were asked to join us in the Bridge House Hotel, Tullamore on Saturday, 27 March. The agenda was broad. The attendance of over eighty people included fifty councillors. As one of our supporters, lawyer Tony Williams, pointed out on that day, we had more councillors there than there were Labour councillors in the entire country. Something was stirring, but that something might be difficult to mobilise.

Finally, Lucinda Creighton had formally launched her party two weeks earlier on 13 March. We were just ahead of the rest of the posse. In June, the Social Democratic Party was formed with no less than three co-leaders: Catherine Murphy, Stephen Donnelly and Róisín Shortall. The field for new groupings was officially crowded.

During that summer, my parliamentary assistant and the only de facto member of staff for the Independent Alliance, Aisling Dunne, completed another tour of Ireland to meet councillors and sign up candidates for the forthcoming general election. She kept the momentum going.

Preparations intensified for a possible autumn election. In September 2015, we hosted our second conference, this time at the Hodson Bay Hotel in Athlone. During the summer we had managed to persuade Senator Feargal Quinn to join us as our chairman. Feargal gave us a huge boost. He was beloved of the media, a widely popular, highly successful entrepreneur. Despite his dazzling business success, he was modest, understated and deeply committed to the independent voice in politics. He had been a fellow university senator with me for nearly twenty years. Nevertheless, I was surprised that he accepted the post so readily because he never engaged in the rough and tumble of domestic politics. The rest of us were street fighters. Feargal had no ambitions for a Dáil seat but, I suspect, might have eyed Áras an Uachtaráin from a dignified distance. Other contributors on the day included Eamon Dunphy, Sinead Ryan, Marian Harkin MEP and Dr Jane Suiter. The Independent Alliance was thriving.

It was a good line-up. Jane Suiter, a lecturer at Dublin City University, was a former economics editor of the Irish Times. Marian Harkin, a long-time independent member of the European Parliament, and Sinead Ryan, a leading journalist on consumer affairs, were heavyweights in their own fields. They spoke with authority and expertise, adding gravitas to the Athlone conference. But Eamon was different. He was box office. The councillors in Athlone on that day, many of them general election candidates, had come to hear Eamon. So had the media.

He didn’t let them down. He promised to support and vote for the Independent Alliance in the coming election. The celebrity football pundit was mobbed afterwards by enthusiastic candidates, seeking to touch his garment and asking him to launch their campaigns. He agreed and delivered in several cases. Eamon Dunphy wanted to be a player.

A few murmurings arose later that evening when it emerged that Eamon had already been flirting with Sinn Féin. He had even been touted as one of that party’s candidates for the coming election. But that is Dunphy, a political chameleon par excellence.

Eamon’s invitation to the Athlone gig was solely my responsibility. I knew it would guarantee us media attention, although there was always a danger that he would say something outrageous. He easily could have damaged us just as we were on a roll. As luck had it, he didn’t.

Eamon Dunphy was probably my oldest friend on the planet. He accepted the gig, at least partly, out of friendship. We had travelled a long road together. Some of it was political, much of it personal. I had been in many scrapes with him over the previous thirty-five years. In our younger days we were as wild as wolves, bonded by booze, nightclubs, journalism and politics. We had enjoyed many all-night sessions, ending up in either the infamous Manhattan café on Dublin’s Kelly’s Corner or, worse still, in the early houses on the river Liffey’s quays. When I ditched the booze, we went out to dinner regularly, in restaurants all over Dublin.

In 2001, Eamon and I challenged the board of Eircom together, using his highly successful Last Word programme on Today FM to mobilise support against the directors. Our campaign culminated in a massive small shareholders’ revolt with 4,000 people baying for blood at Eircom’s annual general meeting in the RDS.

In 2009, I was honoured when Eamon asked me to be his best man at his second marriage, this time to RTÉ staff member Jane Gogan. A seriously talented head of drama, she has generally been a mellowing influence on the seventy-five-year-old tearaway.

In 2011, Eamon and I had joined with two other journalists, the Irish Times’ Fintan O’Toole and the economist David McWilliams, to set up a radical political group, ‘Democracy Now’. We aimed to fight the 2011 general election with all four of us as candidates. We used to plot our strategy secretly over breakfast in the Kildare Street and University Club, on St Stephen’s Green. We took a private room, large enough to fit the four biggest egos ever to gather in a small Dublin location.

The project was doomed from day one. After one of the first breakfasts, I knew we were already in deep trouble when my telephone rang. At the end of the line was Eamon. ‘Fintan has to go,’ he thundered as the price of his continued support. We tottered on for a few more breakfasts until Eamon arrived one morning and announced coyly that he would not, after all, be a candidate. McWilliams soon followed suit, the media found out and the project collapsed.

Nevertheless, I still loved Eamon. He had a big heart. He had been kind to my grandson, Tom, who was mad about football and Manchester United. He came out and campaigned for me in the 2011 and 2016 Dáil elections. He was a huge hit, especially with the more elderly women in the supermarkets who fawned over him. He kissed many of them warmly on both cheeks. It never mattered that he had once been a ‘national handler’ for Garret FitzGerald’s Fine Gael, an infatuated supporter of Mary Harney, Des O’Malley and the Progressive Democrats, and an ally of various Labour candidates. Indeed, he was even two-timing the Independent Alliance, as he was simultaneously in the early days of courtship with Sinn Féin. After the election he told RTÉ’s Claire Byrne that he had voted Fianna Fáil, even though he was supporting me in the adjoining constituency. Eamon lives in Ranelagh, Dublin 6, so he presumably gave his vote to top Fianna Fáil lawyer, Jim O’Callaghan.

That was Eamon, a flawed, contradictory, lovable character. He flaunts his flaws. Eamon has marketed himself as the bold boy, the footballer from Dublin’s disadvantaged north-side who made mistakes and was always in hot water. It was a wonderful formula. Yet he is not all spoof and top-of-the-head soundbites. While his football expertise is widely recognised, it is surpassed by his writing skills. He remains, to this day, one of the most elegant writers of his generation. He made his reputation, in print, attacking icons like Mary Robinson, Seamus Heaney and Jack Charlton, deliberately courting fierce short-term unpopularity. He is a notice box without equal (I should know). Consequently his name is rarely out of the headlines, whether for personal lapses followed by apologies, or political polemics at events like the one we held in Athlone on that September morning in 2015.

Eamon’s political contortions had made him many enemies. I knew on that day in Athlone that his support was a double-edged sword. He probably competes with me for having more ‘former friends’ than anyone else in the country. I was sure of one thing, though. In 2015, we had been comrades for over three decades. Nothing would sunder that friendship. Or so I thought.

As he raised the morale of the troops, I wondered where he would fit into the Independent Alliance? He should be asked by us to promote this new movement in Irish politics. He seemed eager. He volunteered to travel the country to hold meetings of support. He launched Carol Hunt’s campaign in Dún Laoghaire, Marie Casserly’s in Sligo and John Halligan’s in Waterford. He was fully on board. He would undoubtedly have preferred to debate policy and tactics into the long hours of the night. Such sessions would have been entertaining and passionate, but ultimately wherever Dunphy went, he left chaos behind. He was high risk for the Independent Alliance. There was always the chance that he would be a star striker in the first half who scored a series of own goals in the second.

Over the years, Eamon had always joked that if I ever entered government, he would want the chair of Aer Lingus as a reward for his loyalty. Jane would take the chair of the RTÉ Authority. As the possibility of the Independent Alliance achieving office became a reality, he more and more frequently mentioned the attractions of a Taoiseach’s nomination for the Seanad. I never knew whether Eamon was serious about being Senator Dunphy. In subsequent government negotiations, the Independent Alliance was denied any Seanad seats. Enda Kenny’s refusal to give us a single nominee provided me with perfect cover. In any case, I could never have pushed for Eamon to be parachuted into the Seanad. A key pillar of the Alliance’s platform was to banish cronyism.

Initially our friendship survived the Independent Alliance’s transfer from opposition into government. We maintained the frequent telephone calls, the regular dinners and enjoyed a particularly amiable evening with both our wives in late August 2016. Eamon was at his best, telling hilarious stories against himself in Bistro One restaurant in fashionable Foxrock.

Less than a fortnight later, I was listening to Today with Sean O’Rourke on RTÉ. The topic was the strike by Dublin bus drivers. Suddenly I heard a familiar voice denouncing me from a height. He referred to me as ‘Mr Ross’, to my behaviour as ‘scandalous’ and generally insisted that the drivers should be paid a lot more. It was the first of many exocets fired in my direction, without warning and with remarkable venom, over the following months. Eamon, ever a champion of the underdog, lambasted me for not involving myself, as minister, in a very sensitive transport dispute. The attack was more than mildly surprising. At our dinner just two weeks earlier — when the dispute was already well flagged in the media — he had never mentioned the plight of the bus drivers. His passion for their cause must have faltered at the sight of the first glass of prosecco.

Not to worry. Eamon is Eamon. Not Senator Eamon. His point of view had plenty of public support and merit. He was perfectly entitled to express his opinions on any programme and on any subject he chose. I decided not to respond publicly and awaited one of the regular calls we had enjoyed several times a week over many years. It never came. The calls simply stopped.

Fair enough. A few weeks after his outburst on Sean O’Rourke, my mother died following a long illness. The funeral in Enniskerry was well publicised. My friend of so many years did not appear. I was disappointed, for political differences are one thing, but should never sever personal friendships. Maybe, I thought, my oldest pal would drop me a line of solidarity? Perhaps he was away? Sadly, no message of any sort was ever sent. Eamon was the first casualty of the Independent Alliance in government.

But he certainly gave us a great fillip as we entered the Brave New World in Athlone on that September day.

We headed home from the conference that night with a spring in our step. There had been no hiccups or gaffes. Dunphy had behaved himself. The media was really interested and could not ignore us. A roomful of loose cannons had behaved like responsible politicians. But time was short. Enda Kenny was expected to call a November election and we were far from ready. The Alliance had no staff, no organisation, no money and no manifesto. We needed to get down to the hard graft.

We may have had no money, but we did have human assets — five TDs, two senators, over thirty councillors and great ambitions. Tom Fleming, Michael Fitzmaurice, John Halligan, Finian McGrath and I were backed up by Feargal Quinn and Gerry Craughwell in the Seanad. Our seven members of the Oireachtas outstripped Lucinda’s three Renua TDs and two senators, the Social Democrats’ trio of Catherine Murphy, Róisín Shortall and Stephen Donnelly, and the Greens’ tally of zero. The Rural Alliance did not yet exist and Mick Wallace’s left-wing group, ‘Independents 4 Change’, which included Clare Daly and Joan Collins, was not acting as a unit. We were the front runners among the multiple groups competing in the crowded independents’ space.

Tom Fleming and Michael Fitzmaurice carried the torch for rural Ireland at our weekly group meetings. Their contributions reflected similar interests. They also shared one common characteristic: I cannot remember a single occasion when either of them arrived, even vaguely, on time!

Fleming was one of the most unassuming men ever to grace Irish politics. He was universally liked, a trifle innocent for a Kerry TD, but was refreshingly lacking in media savvy or the normal devious ways of politicians. He had been a Fianna Fáil local councillor from 1985 until his surprise election to the Dáil as an independent in 2011. He was originally co-opted to Kerry County Council following the death of his father, then a councillor, and was re-elected at every subsequent election. However, he stood unsuccessfully for the Dáil for Fianna Fáil in 2002 and 2007. Tom resigned from the party after being turned down for a nomination in 2011. It was a good decision, because he sailed into the Dáil, relegating no less a superstar than Michael Healy-Rae into third place. Tom’s membership of the Independent Alliance ensured that Michael kept his distance from us. There was no advantage in two competing independents fighting for votes in one constituency to join the same grouping. Michael ploughed his own furrow but the two men, somewhat unusually in this situation, managed to maintain a personal friendship. We all confidently expected Tom to retain his seat. A banker for the Independent Alliance.

If Tom lacked political guile, his soulmate in the Independent Alliance, Michael Fitzmaurice, carried enough of it in his thumbnail for both of them. Fitzmaurice was an operator who would devour most of his opponents for breakfast. With hands that look as if they could easily lift a tractor, he was nicknamed ‘Shrek’ (after the grumpy ogre of animated movie fame, who lived in a swamp) by the wags in the Dáil Members’ Bar, where he hammed up his rural street cred by always insisting that he drink his coffee in a large mug. He was the natural focus of the rural councillors in the Independent Alliance, because he had positioned himself to be the voice of rural Ireland ever since his by-election triumph a few months earlier. He was not trusted by Mattie McGrath’s wilder gang of rural councillors who wanted to be voices in the wilderness for ever. So the Independent Alliance offered rural TDs an opening, a vehicle for those of them genuinely interested in going into government. Like his patron, Luke ‘Ming’ Flanagan, Michael had been elected principally because of his commitment to the cause of the turf-cutters in the west of Ireland. His power base was the bogs, which he had been cutting since he was four years old. He had personally defied an EU ban on turf-cutting and was chair of the Turf Cutters and Contractors Association. Fiercely intelligent, with an irritating macho manner, ‘Shrek’ was widely expected to outpoll arch-rival Denis Naughten in the general election, whenever it came.

No one could have made less likely partners for Fleming and Fitzmaurice in the Independent Alliance than John Halligan and Finian McGrath. I took an instant liking to John Halligan the moment I met him on our first day in the Dáil — back in 2011. I don’t think it was mutual. He had a wild look in his eye, but was personally engaging. His background in the hard-left Workers’ Party should have been a flashing amber light for a market-led former stockbroker like me. He had been elected as a Workers’ Party councillor in 1999 and 2004, but in 2009 he topped the poll and became independent Mayor of Waterford. I still don’t know why John left the Workers’ Party, but everybody seemed to leave it sooner or later. From time to time, John, who is notoriously indiscreet, would regale us with hilarious, but sometimes hair-raising, tales about his days with his comrades back in the seventies and eighties.

While he was in opposition during the 2011 to 2016 Dáil, he never deserted his roots, but he had definitely seen the benefits of not staying on the backbenches for ever. His Dáil performances were easily the most passionate of all the Independent Alliance TDs. I thoroughly warmed to him one day early in the Dáil term when he landed in the height of trouble with the Ceann Comhairle, Seán Barrett. An out-oforder discussion had erupted in the chamber about a judgement in the Four Courts. John, a heckler with few equals, roared out that the judge in question was a ‘Blueshirt judge’. He had thus broken the nonsensical Dáil taboo that the Four Courts (and above all individual judges) are off limits in the House. He is politically fearless, sometimes reckless and was always unflinchingly loyal. He could be relied upon to bat on the stickiest of wickets for a comrade. He was frequently forced to give his colleagues a dig-out and defend the indefensible in the media. He did it with gusto. We did the same for him. He taught us all that there was, after all, quite a lot to be said for the discipline of a Workers’ Party background. Back in those days it would have been impossible to envisage John as a bedfellow for the Blueshirts.

Finian McGrath came from a similar stable. While John’s mentor might have been the late former socialist president of the Workers’ Party, Seán Garland, Finian’s was undoubtedly the late independent inner-city TD Tony Gregory. All four men were ideologically driven and were firmly on the left of the spectrum. John was originally hard left, but Finian’s background as a primary school principal probably pulled him somewhat closer to the centre. He came to the Dáil as an Independent Health Alliance candidate through the council route in 2002, after sitting on the Dublin City Council since 1999. He was battle-hardened, having stood unsuccessfully for the Dáil on two previous occasions.

Finian was exceptionally popular with Dáil colleagues from all parties. I met him most days in the Members’ Bar for lunch where he held court at the table just inside the door. No TD could enter this Dáil ‘holy of holies’ at lunchtime without exchanging gossip with Finian. He was invariably cheerful, despite the tragic death of his wife Anne, also a schoolteacher, from cancer in 2009. Maybe more than anyone else in the Alliance, Finian was motivated by his own personal experiences. His expertise and passion for those with disabilities was undoubtedly inspired by having a delightful daughter, Clíodhna, with Down’s Syndrome.

Finian had form in government formation. He also had sharp political antennae. Back in 2007, he did a deal with Bertie Ahern and Fianna Fáil to support his fellow northsider’s ill-fated coalition with the Greens. After securing much of his own personal programme, he suddenly jumped ship and ended the deal in October 2008. The deluge followed, but Finian was not on the ship when it sank. The statement he issued on his break with the Fianna Fáil-led coalition summed up his political beliefs: ‘As someone who comes from the tradition of Tone and Connolly, I have to act in the interests of the elderly, the sick and the disabled and the future of our children. I have also supported the call for more patriotism. However, my patriotism does not include hammering the elderly, the sick, the disabled and young children in large class sizes. There are always other creative ways to fund these matters. I have no option but to withdraw my support for the Government.’

A few years later, the man with the picture of Che Guevara in his office was bouncing into bed with the Blueshirts.

And finally, there was me.

In the background, but not in the firing line for the looming Dáil general election, stood independent Senators Feargal Quinn and Gerard Craughwell.

This was the backbone of our team as we headed into battle.

While all five TDs were strong as individuals and were confidently expected to hold their seats, as a team we were one-dimensional. Unfortunately, we were all male. Worse still, the average age of our seven Oireachtas members was a stunning sixty-three. All bar Michael Fitzmaurice were nearing normal retirement age. At our weekly meeting there was far too much fading testosterone in the room. We had a fine logo, but the brand was dismally lacking in fresh female faces.

We needed candidates to contest the election with us who were female and young enough to be our offspring. We needed a manifesto that would be embraced by all the councillors who had signed up at our gatherings in Tullamore and Athlone. It was a tall order but our national coverage and our meetings in the midlands had fired up enthusiasm for a challenge to the big parties. While we had not managed to attract sitting women deputies or senators to our ranks, countrywide women councillors had come calling.

We spent nearly six months in search of recruits with a different profile. We systematically interviewed councillors or others who saw our project as a vehicle for reform.

In Dublin one of Ireland’s most vocal newspaper columnists, Carol Hunt, was an early supporter. Carol ended up as our only woman candidate in the general election who was not a councillor. Her motivations were so noble that I gulped twice over my coffee when I met her in Buswells Hotel during the search for candidates. Carol was refreshing. She had ideas and integrity. She thought that it was time for her to become involved in public life. She felt an obligation. Her opinions in the Sunday Independent were the most articulate expression of militant feminism in the media in 2015. She believed it was incumbent on someone who expressed so stridently what was wrong in political life to pick up the gauntlet and practise what she had been preaching in her columns.

Carol was different. Unfortunately, she lived in Dublin’s inner city, an almost unassailable political fortress for a new candidate. The mantle of local legend, the late Tony Gregory, had long ago been inherited by one of his closest followers, independent Deputy Maureen O’Sullivan. We had tried to attract Maureen to join us in the Independent Alliance, but she had declined. No other independent had a chance of competing with Maureen for the Gregory legacy, besides which Maureen was a hard worker and one of the most idealistic members of the Dáil. Worse still for Carol, Dublin Central had four incumbents, now fighting for only three seats since the constituency had lost one seat to become a three-seater in 2016. Apart from Maureen, the remaining three seats were held by outgoing cabinet minister Paschal Donohoe, Sinn Féin’s Mary Lou McDonald and Labour’s Joe Costello. Joe was toast, but if Carol was to capture a seat she needed to topple a political giant, either Paschal or Mary Lou. Instead, she decided to head across the Liffey to Dún Laoghaire, where she had grown up and still had strong family ties.

Elsewhere in Dublin we recruited two utterly different women, both hell-bent on taking seats in their respective areas. Deirdre O’Donovan had volunteered for my 2011 Dáil election campaign in a resolute effort to remove Fianna Fáil from office. Three years later — in 2014 — she was elected to South Dublin County Council, an area that included Tallaght. She was as keen as mustard to run for us in 2016 on an anti-big party platform with a community emphasis. We embraced her — as someone with such naked ambition — with open arms. Deirdre was hungry.

Just as Carol Hunt had Maureen O’Sullivan blocking her chances, Deirdre had her own high-profile, independent obstacle in the Dublin South-West constituency. Senator Katherine Zappone, who ultimately ended up as an independent minister in Enda Kenny’s cabinet, had done good work in Tallaght on the Tallaght West Childhood Development Initiative, adding a local base to her high national profile. Deirdre, unimpressed by the big gun in her bailiwick, powered on, dismissing Zappone’s chances of success and convinced that she herself would be swept into a seat for the Independent Alliance.

On the other side of the political spectrum — and on the other side of the Liffey — Lorna Nolan was a radical Fingal County councillor from the Mulhuddart ward. She was as hard-working as councillors come, a senior social care worker dedicated to suicide prevention, drugs rehabilitation programmes and people with disabilities. Lorna is one of those women who is far too good for politics. She was deeply committed to the Alliance because she saw it as a way to promote the minority causes she championed, never as a route to self-advancement. We were devastated when she was forced to withdraw as a candidate at the last minute because her brother became seriously ill.

We had wooed some mighty women from Dublin. Outside Dublin, the numbers of women councillors committed to our cause were fewer than the numbers hovering around the edges, eager but unwilling to take the plunge. They were hampered by our inability to offer them funds for a campaign, because the Independent Alliance qualified for no public money. The entrenched parties have long ago stitched up state funding available for political activities. Independents are forced to fund election campaigns from their own resources or from voluntary donations. Nevertheless, we fielded three serious women contenders, itching to take the big parties apart in Donegal, Louth and Sligo.

We were immensely proud of both our women candidates in the north-west: Councillor Marie Casserly in Sligo-Leitrim and Councillor Niamh Kennedy in Donegal. We knew they both had mountains to climb, fighting Dáil constituencies where traditional loyalty to established civil war parties still dominated.

Unfazed, Marie Casserly decided to enter the fray. An Irish teacher and guidance counsellor at St Mary’s College in Ballysadare, Marie was a serious contender. A teacher, a mother of five children, a feminist who helped to found the Grange men’s shed, was exactly the kind of community activist we needed to broaden our brand. We had to twist her arm to run because she was motivated by passion for her area, not personal ambition. Nothing moved in Sligo of which Marie was unaware. She was unrelenting in badgering ministers on behalf of her home patch and she was an unrepentant advocate for her ‘neglected’ region. A health enthusiast, she found time to support all local sports clubs and to promote cycling. She was delighted when Eamon Dunphy launched her entry into national politics.

Farther north, Niamh Kennedy flew the flag in the bearpit that is the constituency of Donegal. Anyone caught in the crossfire between such battle-scarred veterans as Fine Gael’s Joe McHugh, Sinn Féin’s Pearse Doherty, Fianna Fáil’s Pat (the Cope) Gallagher and Charlie McConalogue needs to be made of stern stuff. Niamh is. In 2014, she was the first ever independent councillor elected to Donegal County Council. Based in Killybegs, she originally worked in the fishing industry, in both administration and health and safety. More recently she and her husband have run an electronics business. At one point, Niamh was approached by Fine Gael, but happily she spurned the Blueshirt blandishments.

Yet, despite the rich offerings, not a single woman was elected to any of the nine seats in Donegal and Sligo-Leitrim.

While Marie and Niamh were enlightened political outsiders in two of the most rural parts of Ireland, Louth was a real live runner for an independent seat. Maeve Yore from Dundalk was elected to the Louth County Council in third place in the 2014 local elections with a substantial 1,228 votes. She was well placed in the north of the county, had a proud community record, having worked in the Credit Union for fourteen years, and was a founder member of Special Needs Active Parents (SNAP). She was disarmingly blunt in conversation and regularly discarded her natural charm in pursuit of an objective for people with special needs. It often worked. She was highly respected in Dundalk for her steadfast integrity. Unfortunately, her fame did not stretch beyond Dundalk, where she was guaranteed to reap a good vote. She needed a running mate who would deliver votes from the south of the county, namely Drogheda.

Maeve had a potentially ideal running mate in Drogheda. Councillor Kevin Callan had been a Fine Gael mayor of Drogheda in 2011 but had resigned from the party over the water charges, to become an independent in 2014. Kevin was intent on standing for the Dáil. He and Maeve were a perfect fit. One seat was there for the taking provided they agreed on a vote transfer pact. Kevin and Maeve seemed to be a dream ticket to land one of Louth’s five seats. Sadly, they were never able to agree on a sensible division of the county.

While our search for candidates met with multiple successes, one ended in a tragedy. Councillor William Crowley from Newbridge, County Kildare, was an enthusiastic promoter of the Independent Alliance, determined to run for us in the constituency of South Kildare. Willie came to Dublin to meet the Independent Alliance deputies one afternoon and dazzled us with his enthusiasm, his experience in politics and his community involvement. I knew him, but only by reputation, as the man who had met Michael Noonan about the future of the troubled Newbridge Credit Union. As that meeting started, Willie opened up: ‘Before we begin, Minister, I would like you to tender your resignation in the Dáil tomorrow.’ It was a novel approach from a county councillor seeking a sympathetic audience from a senior minister. Willie was a freelance journalist and a highly successful small businessman, setting out on a career in national politics at the age of sixty-five. We were delighted that he had agreed to run for the Independent Alliance.

It was not to be. On 18 December 2015, Willie was mowed down on the streets of Newbridge by a hit-and-run driver just a hundred yards from his home. I was among several public representatives at his huge funeral in St Conleth’s, Newbridge, where there was a clear outpouring of grief from the whole community. His death was a terrible loss to his family, to Newbridge and ultimately to Dáil Eireann.

We met all the candidates before giving them our imprimatur. In return, they agreed to sign up to our principles — a ‘Charter for Change’ as it would eventually become. We did not accept the approaches of all those looking for the blessing of the Independent Alliance. Sometimes we had to make choices between two independents in one constituency. At other times, the prospective candidate turned down our approaches, feeling that joining a group, albeit a loose alliance, could compromise their freedom. Some opted to run solo without being attached to us. Others joined the Greens or the Social Democrats. Generally, those who were not frightened of being in government signed up, while those who probably felt more comfortable in opposition declined.

One of those gagging to join us was none other than a man with the familiar name of Peter Casey, an investor on RTÉ’s Dragons’ Den business programme. He was supposed to be a heavy hitter with a great career behind him. When he rang looking to meet me, I was chuffed. Here was a TV star on the Dunphy scale seeking our support. Casey had founded an outfit called Claddagh Resources, a global recruitment company that placed executives with many Fortune 500 companies. Claddagh had made him a multi-millionaire. His dazzling business success and television stardom made me think he might be a bit above our pay grade.

The problem was, so did he. I met him on a number of occasions. Never before — or since — in my political life have I encountered a candidate with such delusions. Peter, who lived in the United States, was going to build the biggest house in Donegal and would therefore win a Dáil seat. He ignored my protests that we already had a wonderful candidate in Niamh Kennedy, who had an impeccable record as a county councillor. The idea of defeat in an Irish election never occurred to a man who spent most of his time making his fortune in the US. His ego had reached a level that would have made Dunphy blush. I invited him to our conference in Athlone, hoping that he might be afflicted with a shock dose of realpolitik and be halted in his tracks from aping Donald Trump on speed.

I can only guess that he took my advice and spent some of his vast riches on an opinion poll in Donegal. He dropped the idea of running on our ticket and disappeared. To my great relief, he opted for the Seanad election. There, his balloon was pricked. Casey stood on the Industrial and Commercial Panel, having been foolishly nominated by the Irish Business and Employers Confederation (IBEC). The quota was 113 votes. He received 14.

A lucky escape for the Independent Alliance. Unhappily, Peter Casey resurfaced in 2018. Originally a no-hoper candidate in the presidential election, he unashamedly played the racist card to boost his chances. His last-minute piece of insidious rabble-rousing, plugging into anti-traveller prejudice, raised his poll ratings from 2% to 23% by election day. He was runner-up to Michael D. Higgins.

Peter Casey’s performance in the battle for president hardly dented Michael D.’s triumph, but it swelled the challenger’s already inflated head. In the wake of the result, he suddenly declared that he wanted to lead Fianna Fáil, but was surprised that the disciples of de Valera had a distinct lack of appetite for a messiah who was not even a party member. Undeterred, he stood as an independent for the European Parliament in 2019, again failing to pass the winning post. Disregarding a succession of rebuffs, he decided to double down in the 2020 general election, spurning the idea of winning merely one single seat. Instead, he wanted two! Voters in both Donegal and Dublin West were honoured to find Casey’s name on their ballot papers on the same day. He scraped a small (1,143) vote in Donegal, where he expected to do well. Worse still, in a final piece of grotesque vanity, he challenged Taoiseach Leo Varadkar in his home patch of Dublin West. Casey’s vote was a derisory 495 against the Taoiseach’s 8,478.

We had certainly attracted enough women and men to counter criticism from those opponents who wagged the finger, insisting that we merely represented one gender and one generation. Several younger males were also on the Independent Alliance ticket. We had high hopes of Paul Gogarty (a former Green Party TD, then an independent) retaking the seat he lost in Dublin Mid-West in the 2011 election.

Gogarty was one of the most colourful TDs during his nine years in the Dáil from 2002. His highly unorthodox outbursts tended to distract from an appreciation of the good work he did for Irish education during his time in the Dáil. To his credit, he played a leading role in protecting education from cutbacks when he was chairman of the Oireachtas Committee on Education and Science under the Fianna Fáil-Green government. But the public was probably more aware of the time he let fly at Labour’s Emmet Stagg during a debate on social welfare in 2010. After being niggled by Stagg’s heckling, Paul lost the head. ‘With all due respect, in the most unparliamentary language, fuck you, Deputy Stagg, fuck you,’ he exclaimed. He immediately apologised, but a complaint from Fine Gael’s Lucinda Creighton followed. The incident was referred to the Dáil’s Committee on Procedure and Privileges after it was found that the ‘F’ word was, surprisingly, not on the list of expletives forbidden by the House’s rules!

In another controversial incident, Paul again landed in hot water after he brought his eighteen-month-old daughter to a Green Party press conference, claiming that his childminder was not available. He was a wild card with good ideas and was a live prospect for an independent seat.

Elsewhere — in the Midlands — we knew that Kevin ‘Boxer’ Moran had a sporting chance of a win in Longford-Westmeath and — in the West — Seán Canney was a firm favourite to score a gain for us in Galway East. Both were long-time councillors with a record of hard work which was likely to carry them over the line. Another who might have pulled a surprise if he had been able to agree a vote transfer pact with fellow independent Joe Hannigan was former Fianna Fáil member, businessman and councillor John Foley in Offaly. He couldn’t, so his chances were dramatically reduced.

We were not going to allow any no-hopers to stand under our banner. All bar Carol Hunt, Boxer Moran’s running mate James Morgan, and Diarmuid O’Flynn of the ‘Ballyhea Says No’ anti-bailout campaign, were already councillors, so had recently tasted electoral triumphs and established a local base in their larger Dáil constituencies. Tony Murphy (Dublin North), Joe Bonner (Meath East), Ger Carthy (Wexford) and Mick Finn (Cork South-Central) were experienced candidates with strong showings under their belts.

We had a good team of twenty-two, but in October 2015 we were far from ready for Enda Kenny to blow the whistle. Thankfully, he didn’t.

Enda bottled the most important political decision of his life. Late in 2015, the Taoiseach had encouraged speculation that he would call an election in November. He was reported to be under heavy pressure from both Finance Minister Michael Noonan and European Commissioner Phil Hogan not to leave the contest until February 2016. Enda’s personal standing in the polls was at a high point, Fine Gael was recovering after four years of austerity and unemployment was falling. His TDs, including his Mayo constituency colleague Michael Ring, were upbeat about their chances. Many of the Blueshirts wanted to avoid the seasonal winter political pitfalls of ill health and homelessness.