Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Al-Mashreq eBookstore

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

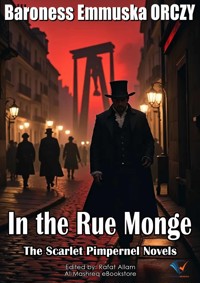

In the blood-soaked streets of Paris during the French Revolution, even a whisper of betrayal can mean death. In the Rue Monge follows one of the Scarlet Pimpernel's most daring missions, as Sir Percy Blakeney plunges once more into the heart of revolutionary terror. When an innocent aristocrat faces the blade of the guillotine, Percy must employ all his wit, cunning disguises, and reckless courage to outsmart the relentless Revolutionary guards. But in the narrow, twisting alleys of the Rue Monge, danger lurks at every corner — and even the smallest mistake could mean exposure. Rich with suspense, romance, and Orczy's trademark flair for high-stakes intrigue, this tale captures the essence of the Scarlet Pimpernel legend: that even in an age of cruelty, one man's daring could inspire hope.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 31

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

In the Rue Monge

Table of Contents

In the Rue Monge

1

2

3

Landmarks

Table of Contents

Cover

1

The Professor swung himself round on the high stool on which he was sitting, and blinked tired, watery eyes at his interlocutor.

"You were saying, milor'?" he asked in his shaky, high-pitched voice.

And the other resumed with exemplary patience:

"I was trying to explain to you, my friend, that no one is safe these days, and that at any moment one of those devils on the Committee of Public Safety might set your name down on the list of the suspects. Now, I promised your daughter over in England that my friends and I would look after you; but even without such a promise—"

He paused, for obviously the little man was not really listening. He had begun by trying to be attentive, by trying to understand the import of what his friend was saying; but his attention was already wandering and his pale, tired eyes were turned longingly in the direction of his test-tubes, his microscopes and other scientific paraphernalia which littered his table. Now, when his friend ceased speaking, he again tried to appear interested.

"Yes, yes, my daughter!" he murmured vaguely. "Pretty girl, she was. Married that nice man Tessan; a prosperous farmer he was. They were on their honeymoon in England when this awful revolution fell upon us here. Lucky for them! They were never able to return to France."

He continued to ramble on in this vague, inconsequent way; his friend listened to him with undivided attention. They were such a strange contrast, these two: the powerfully-built Englishman, dressed simply but with scrupulous care, a man with finely-moulded hands and lazy, grey eyes that had at times marvellous flashes in them of enthusiasm and command—a leader of men, obviously, a fearless sportsman and daring adventurer—and his learned friend, a man with wizened body and spine prematurely bent, with noble, thoughtful forehead and timid, quivering mouth. A worse-assorted pair could not easily be found. But they were friends, nevertheless. It was a friendship based on mutual respect, even though there was on the one side a strong element of protective affection and on the other a timid, almost childlike trust.

"I would like to go to England with you some day, milor'," the professor went on with a yearning little sigh. "I believe I could do great things in England. I could meet your famous Jenner and show him some of my own experiments in the field of vaccine. These are not altogether to be despised," he added, with a quaint chuckle of self-satisfaction. "And, believe me, my friend, this Revolutionary government is not made up of asses. They have a certain respect for science, especially for the curative sciences; they know that sickness stalks abroad in spite of all their decrees and their talk of a millennium, and they are not likely to molest those of us who work for the better health conditions of the people."

The Englishman said nothing for a moment or two. He regarded his ingenuous little friend with a kindly, gently-mocking glance. At last he said:

"You really believe that, do you, my good Rollin?"

"Yes, yes, I believe it. I had the assurance lately of no less a personage than the great Couthon, Robespierre's bosom friend, that the Committee of Public Safety will never touch me while I carry on such important experiments."