Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

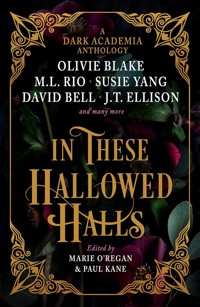

ENROLLMENT BEGINS NOW A beguiling, sinister collection of 12 dark academia short stories from masters of the genre, including Olivie Blake, M.L. Rio, Susie Yang and more! In these stories, dear student, retribution visits a lothario lecturer; the sinister truth is revealed about a missing professor; a forsaken lover uses a séance for revenge; an obsession blooms about a possible illicit affair; two graduates exhume the secrets of a reclusive scholar; horrors are uncovered in an obscure academic department; five hopeful initiates must complete a murderous task and much more! Featuring brand-new stories from: Olivie Blake M.L. Rio David Bell Susie Yang Layne Fargo J.T. Ellison James Tate Hill Kelly Andrew Phoebe Wynne Kate Weinberg Helen Grant Tori Bovalino Definition of dark academia in English: dark academia 1. An internet subculture concerned with higher education, the arts, and literature, or an idealised version thereof with a focus on the pursuit of knowledge and an exploration of death. 2. A set of aesthetic principles. Scholarly with a gothic edge – tweed blazers, vintage cardigans, scuffed loafers, a worn leather satchel full of brooding poetry. Enthusiasts are usually found in museums and darkened libraries.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 461

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Introduction | Marie O’Regan and Paul Kane

1000 Ships | Kate Weinberg

Pythia | Olivie Blake

Sabbatical | James Tate Hill

The Hare and the Hound | Kelly Andrew

X House | J. T. Ellison

The Ravages | Layne Fargo

Four Funerals | David Bell

The Unknowable Pleasures | Susie Yang

Weekend at Bertie’s | M. L. Rio

The Professor of Ontography | Helen Grant

Phobos | Tori Bovalino

Playing | Phoebe Wynne

About the Authors

About the Editors

Acknowledgements

ALSO AVAILABLE FROM TITAN BOOKS

FANTASY

Rogues

Wonderland: An Anthology

Hex Life: Wicked New Tales of Witchery

Cursed: An Anthology

Vampires Never Get Old: Tales With Fresh Bite

A Universe of Wishes: A We Need Diverse Books Anthology

At Midnight: 15 Beloved Fairy Tales Reimagined

Twice Cursed: An Anthology

The Other Side of Never: Dark Tales from the World of Peter & Wendy

Mermaids Never Drown: Tales to Dive For

CRIME

Dark Detectives: An Anthology of Supernatural Mysteries

Exit Wounds

Invisible Blood

Daggers Drawn

Black is the Night

Ink and Daggers

SCIENCE FICTION

Dead Man's Hand: An Anthology of the Weird West

Wastelands: Stories of the Apocalypse

Wastelands 2: More Stories of the Apocalypse

Infinite Stars

Infinite Stars: Dark Frontiers

Out of the Ruins

Multiverses: An Anthology of Alternate Realities

HORROR

Dark Cities

New Fears: New Horror Stories by Masters of the Genre

New Fears 2: Brand New Horror Stories by Masters of the Macabre

Phantoms: Haunting Tales from the Masters of the Genre

When Things Get Dark

Dark Stars

Isolation: The Horror Anthology

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

In These Hallowed Halls

Print edition ISBN: 9781803363608

E-book edition ISBN: 9781803364193

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd.

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First Titan edition: September 2023

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Introduction © Marie O’Regan and Paul Kane 2023

1000 Ships © Kate Weinberg 2023

Pythia © Olivie Blake 2023

Sabbatical © James Tate Hill 2023

The Hare And The Hound © Kelly Andrew 2023

X House © J. T. Ellison 2023

The Ravages © Layne Fargo 2023

Four Funerals © David Bell 2023

The Unknowable Pleasures © Susie Yang 2023

Weekend At Bertie’s © M. L. Rio 2023

The Professor Of Ontography © Helen Grant 2023

Phobos © Tori Bovalino 2023

Playing © Phoebe Wynne 2023

The authors assert the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

INTRODUCTION

Marie O’Regan and Paul Kane

Dark Academia.

What do those words conjure up for you? Mysterious and dangerous occurrences in various seats of learning? Students, and sometimes their tutors, in peril? Murder? Magic? Ghosts? Dusty books in old libraries? Clandestine cults and secret societies devoted to ancient rituals? All or none of the above?

If you’re new to the subject, you’ve picked the perfect place to start. If you’re already a fan, then we think you’re going to love what we’ve got in store for you within these pages! In the last few years the phenomenon of Dark Academia has, quite literally, exploded. Fuelled by book clubs on social media platforms like Tumblr and Instagram, where people discuss classic and Gothic books, this wave developed into a subculture in its own right that grew even more popular during the pandemic and lockdowns. Let’s face it, there wasn’t much else to do during those times than watch things and read.

Books like Donna Tartt’s The Secret History, the Harry Potter series and classics such as Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray and the ghost stories of M. R. James have all been credited as inspiring the trend, as well as films like Love Story, Dead Poets Society and Cruel Intentions, not to mention more recent TV shows like A Discovery of Witches (based on the excellent novels by Deborah Harkness), A Series of Unfortunate Events and The Queen’s Gambit, which all helped to fan the flames.

So, you can imagine our delight when we were asked to edit this anthology and gather together some of the finest exponents of this type of fiction around. Author of The Atlas Six and The Atlas Paradox, Olivie Blake, brings you a timely and unique social commentary – which still connects to the past – in her story “Pythia”, while M. L. Rio (If We Were Villains) reminds us of the pitfalls and potential benefits of being in the wrong place at the right time – or perhaps that should be the right place at the wrong time? – in “Weekend at Bertie’s”.

The author who brought you novels such as Good Girls Lie and Her Dark Lies, J. T. Ellison, and Tori Bovalino – who wrote The Devil Makes Three and Not Good for Maidens – show us the real dark side of Dark Academia in “X House” and “Phobos” respectively. Whereas Helen Grant (Ghost and Too Near the Dead), Layne Fargo (Temper and They Never Learn) and Kelly Andrew (The Whispering Dark) introduce us to the disturbing strangeness of the subject in “The Professor of Ontography”, “The Ravages” and “The Hare and the Hound”.

Both Kate Weinberg and James Tate Hill return us to the worlds of their books (The Truants, and Blind Man’s Buff, Academy Gothic) in their stories “1000 Ships” and “Sabbatical”. Author of Kill All Your Darlings and The Finalists, David Bell, presents us with a thought-provoking tale, “Four Funerals”, that will stay with you long after you’ve finished reading it, as will Phoebe Wynne’s (Madam, The Ruins) story “Playing” and its intriguing insights. All this plus Susie Yang (White Ivy) and her meditation on relationships, secrets and longing, “The Unknowable Pleasures”.

Excellent contributions by authors writing at the top of their game, showing the full range and power of what Dark Academia can do. So, settle back in your favourite reading spot with your favourite tipple, preferably surrounded by books, and let the lessons begin!

Marie O’Regan and Paul KaneFebruary 2023

1000 SHIPS

Kate Weinberg

The window seat had the perfect view across the college quad. Right now, in the late-autumn morning light, it looked too pretty to be real. The paving stones glistened from last night’s rain, the tall sundial column in the centre of the courtyard threw its skinny shadow towards the ivy-fringed archway by the porter’s lodge, and the sun striking off the honey-coloured limestone buildings bathed everything in a golden glow.

Lorna retied the slithery silk dressing gown (which, being his, was baggy around the shoulders and too long) and wrapped it about her bare legs, before leaning back against the folds of the curtain. She could still hear his footsteps echoing down the stairwell beneath. Any moment now he would reach the heavy door that led onto the courtyard, she’d hear the thud of it shutting… and there he was, swallowing up the large courtyard with his long, purposeful gait, the wine-coloured scarf she’d given him for his birthday flying behind him, his dark hair lifting with every stride.

She watched as he paused to turn up the collar of his black coat, against the chill, or perhaps just because; along with the single earring, skinny black jeans and trainers, this was his trademark look. No pipe and tweeds, or corduroy jackets with elbow patches for the forty-year-old, handsome Dr Chris Chase (dubbed “Kisschase” by most of the student population, although since this latest incident an article had published in one of the student magazines with a headline calling him Dr Death).

Even from this bird’s eye view he emanated his usual confidence. No sign at all that this was judgement day, that his career and reputation were on the line. “Not remotely worried,” he answered as he leaned down to kiss her goodbye, smelling of toothpaste and aftershave, so that she’d closed her lips, feeling self-conscious of her gritty morning breath, last night’s red wine furring her teeth. “They have nothing on me apart from a bit of malicious gossip and some wild accusations from grieving parents. They are barking up the wrong tree. If the old farts could see what I’m looking at right now…” he planted little kisses between her breasts, then on her neck, “they’d sack me, then have an existential crisis and leave their wives and jobs.”

There was no doubt the situation made the sex better, thought Lorna. It felt like they’d started sleeping together ten days ago, rather than ten months. After last night’s debacle, they’d woken up early that morning (they never slept long in his teaching room, it was a single daybed after all) and lying side by side, ran through everything he was planning to say to the board. How Chris had done quite the opposite of putting pressure on this poor young man who was clearly overwhelmed, despite being very gifted, and struggling socially. How he entirely refuted any rumours that he had made this sensitive young person feel worthless or inadequate in class. On the contrary he, Chris, was the one who had urged him to seek professional advice, who had told him to take as much time off his studies as he wanted, to read purely for pleasure. Every college has their own politics, he would tell the old farts. Indeed, he would like to suggest that alongside supporting this unfortunate young man’s family, and student mental health in general, the college would do well to focus less on the mythology around his teaching methods and more on the vested interests within the faculty itself, about who may stand to gain from stirring up scandal around a teacher who had delivered more First-class honours in the last six years running than at any other time in the college’s history.

As he was rehearsing Lorna rolled on top of him, legs straddling his groin, feet flexed and asked him what would happen, worst case, if they decided he had in any way contributed to his suicide? Would the case become criminal – she felt him growing hard beneath her – and if so, could they link it to what happened four years before with the other student? So that when he had lifted himself slightly to jerk her towards him, his fingers biting into her upper arms, she’d felt the thrill of his urgency for her that she hadn’t felt so sharply since the first time they’d fucked.

Now sitting in the window seat, she slid her right hand down the left sleeve of her dressing gown and pressed one of her bruises lightly. It would be a pale violet now, a purple that would deepen and acquire more ochre by the end of the day. Marks like this were commonplace after sex. Did she really like it, his roughness – she had once felt her rib was close to actually cracking – or did she provoke it because she enjoyed his loss of control, the transfer of power in that moment, so different from the omnipotent figure he cut in tutorials and lecture halls? It was a question she asked herself from time to time, with a kind of detached curiosity. As if the answer would be interesting, rather than materially relevant to her choices.

Chris had paused now, at the far side of the quad, to talk to a girl with long dark hair. Just a few steps before reaching the porter’s lodge, at a diagonal towards where she was sitting, where the rose bushes normally bloomed. Lorna leaned forward to get a better view. But she had guessed, somehow, even before she recognised her. Alicia Evans. English fresher. Three weeks into the start of the academic year, and already famous as the new college beauty, with her olive skin and curves, the chain belts that were slung uselessly around her tight, low-hipped jeans, the red gypsy blouses cut too low for the weather.

As a Second Year, Lorna had seen it happen before: the sudden feeding-frenzy around the newcomers, the swift judgements and categorisation, before the adjustment of hierarchy as a kind of composite equation. Beauty; brains (beauty plus brains scored highest; beauty next; brains on its own was a matter of interest rather than sexual power) and then something more amorphous, some quality that had to do with humour or presence or charisma that had its own valency, though no one could rank it easily, that made people flock around, seeking favour.

A few moments ago, Lorna had been anticipating a shower, lathering herself luxuriously with all his gels and soaps. Now she stayed where she was, breathing steamy spots onto the glass, watching them. She remembered the first time she’d used the bathroom in the middle of a tutorial, before the affair started. The shock of the full-length mirror leant against the wall opposite the shower, that felt like a provocation, the way she’d carefully opened his mirrored cabinet and snooped amidst his things. And then the first time they’d made love, two weeks later, her thighs wrapped around his, his hand pressing against the tiles so that, in the reflection of the mirror she could see the piston of his arse, her locked calves, the water sluicing down between his shoulder blades.

Chris had put his satchel down on the paving stones. Now he was moving around to lean against the wall, one foot resting up, as if settling in for a chat. What was he doing? It was a fifteen-minute fast walk to the Dean’s house where the hearing was taking place. What the hell could Alicia, three weeks into starting his classes, need to discuss with him so badly? Or him with her? Lorna felt again for the bruise above her elbow and pressed. Ten seconds, twenty. She applied more pressure, feeling the ache radiate through her arm. Perhaps it was three minutes later – she had stopped counting, to focus on the pain – when he picked up his satchel, and walked out with the same purposeful, forward-leaning stance with which he’d strode into their first group tutorial.

* * *

“Vilia miretur vulgus. Can anyone tell me what that means? Literally, of course, but also about the mindset of Shakespeare. The kind of man he was?”

Dr Chase sat to the side of his desk, on a leather chair, waggling a pen between two fingers.

Of the six students sitting cross-legged on the circular carpet beneath the window seat, no one spoke. They were looking anxiously at the title page of Venus and Adonis, the long narrative poem that they’d been asked to read before the tutorial. Most people, Lorna included, had made pages of notes, read every footnote, consulted books of literary criticism before class. No one had thought to bother with the florid dedication before the poem began. An hour into the tutorial and Lorna, although initially awed like the rest of her cohort, was beginning to dislike him. There was a cold attentiveness to the way he listened to answers, as if nothing could surprise or impress him. You’re not clever; you may be clever; you’re clever, but not original he seemed to be signalling with every chilly appraisal. She disliked herself, too, for how much she wanted to impress, how hard she racked her brains to exhume her schoolgirl knowledge of Latin and the conversational Italian she’d picked up in her year off, waitressing in Sicily. She was fucked if she was going to stick up her hand, like an eighth grader, so she cleared her throat into the silence.

“Vulgus means ‘the common people’ I think,” she said slowly. “And miretur… well it’s a guess, but I’d say some declension of the verb ‘to admire’.”

Those cool blue eyes flickering over to her, the slightest of nods.

“And vilia, Ms Clay,” he asked. “Tell us what vilia means. And therefore, what young Will Shakespeare was thinking when he picked this particular quote from Ovid’s Amores to appear on the front page of his first published work?”

Lorna held his gaze, feeling the colour rise in her cheeks. It felt for a moment like she was on a slab, in an operating theatre, under some unforgiving, fluorescent lights, being examined by a surgeon as a series of moving parts.

“Pity,” he murmured, looking away.

Then he addressed the group. “Vilia means ‘trash’. So, ‘the common people’, as Ms Clay puts it in her textbook way, I prefer ‘mob’ or ‘rabble’… Themob admires trash. Why do we think the thirty-year-old Shakespeare would make this statement to his patron?”

A boy with shoulder-length hair, round face and a snub nose put up his hand.

“False modesty?”

Chris Chase barely graced him with a look. “Anyone else? No. Disappointing.” His eyes switched back to Lorna.

She shrugged. “Pre-publication nerves?”

He gave an unexpected smile. “Closer. What we can say is that we feel in him, from the very beginning, a deep cynicism, perhaps even misanthropy. An intellectual and moral snobbery. Shakespeare is famous for his great humanitarian themes, his genius at empathy, his understanding of the lot of the common person every bit as well as the educated noble person. But perhaps we should allow ourselves to question this deification… Perhaps,” Dr Chase sat back in his chair and folded one ankle across his knee, playing with the laces of his gym shoe, “the great playwright’s writing persona was carefully constructed. Maybe Shakespeare was more like one of the brilliant but cynical minds that work these days in big Hollywood studios, who know how to elicit an emotional landscape that they don’t necessarily feel. In other words, let us bin all assumptions about Shakespeare. Let us rid ourselves of any sentimentality and approach his text as any other.”

“What did you think?” the boy with the shoulder-length hair asked Lorna as they all clattered down the stairwell afterwards.

“I thought it was bollocks,” said Lorna, surprised at the heat in her voice. “Attention-grabbing, contrary bollocks. I don’t see why everyone makes a big fuss about his teaching.”

But she found that, in the days after, his cool appraising eyes kept surfacing in her head. When she was in the dining room, she caught herself scanning the top table, not sure why, but hoping she would catch a glimpse of him.

It wasn’t until the week after when she was in the bar, waiting for a friend to arrive that some third-year English students, three men in black tie, heavy on hair gel, light on chins, called over to her. “Want a drink? Hear you’re Kisschase’s new favourite.”

“Fat chance,” she replied quickly. “I mean yes please to the drink, fat chance about… Dr Chase.”

“Afraid so,” said one with even less chin than the others. He had large, slightly bulging eyes and a flick of coiffed blond hair. “You’re his new Helen of Troy.”

She shook her head. “That’s ridiculous.”

“He picks one every year. You scored higher than last year’s lot, too. He told us, watch out for Lorna Clay. 1000 ships. No one’s fool, either.”

* * *

Lorna swung her legs off the window seat, so that her bare feet hit the cool radiator below, and looked over at the empty circular carpet where they’d sat that day, before the tutorials were split into one-to-ones. At the time, being a fresher, she hadn’t realised how unusual it was to have students sitting on the floor. Perhaps he liked the feeling of students at his feet. A modern-day Socrates, dispensing his wisdom. She glanced back out the window, at the now empty quadrangle.

Normally Lorna left his room before him, so it was unusual for her to be here on her own.

She showered without the pleasure she’d been anticipating. Perhaps the reality of the hearing, and what may happen to him was beginning to sink in, perhaps it was an instinct or paranoia around Alicia Evans, but she felt uneasy suddenly, as if something was reaching a tipping point. It wasn’t until she was combing her wet hair back in front of the fogged mirror, and noticed the scissors still on the side of the sink, that she looked down into the wastepaper basket and thought about last night.

She’d woken in the dark, with him reaching for her. She’d been bleary, and within moments he had manoeuvred her into her least favourite position, him entering from behind, one hand on the small of her back, her face a few inches from the pillow as he bumped behind her. Then, clearly audible between his groans, a click and a whirr.

She hadn’t stopped him until he came. Looking back, maybe that had added to her sense of resentment. She had allowed him to reach his peak, her desire having switched off like a plug ripped from the wall before she’d asked him what she’d heard. He grinned a little sheepishly in the gloom and picked it up from the floor by the side of the bed, a polaroid camera.

“You looked so sexy. I thought you’d find it a turn-on,” he said, and he seemed embarrassed as she switched on the light to study the photo, the ignominy of the angle. “I got carried away. I should have asked.”

“You should have,” Lorna said, taking the photo off him and thinking that it’s pretty hard to get “carried away” when you’ve purposefully placed a polaroid camera within easy reach, before the act.

After he’d fallen asleep she’d been restless, had got up and fetched scissors from his desk before picking up the photo, walking into the bathroom and cutting it into tiny pieces under the cold bathroom light, then sprinkling them like confetti into the wastepaper basket.

Now she dried and dressed herself, watching the steam disappear from the mirror. His desk was a mess as usual. Piles of essays, some marked, others not. Printouts. Books. Somewhere on that desk would be an essay by Alicia Evans, the first she’d submitted to him. She wondered if he’d summon her to his room to talk about it, too.

* * *

“Do you know why I asked you here?” said Dr Chase. It had been a late-autumn day, as well. Cold and misty though. No Indian summer last year. Lorna had shrugged at the question, still feeling defensive after that first tutorial, although he seemed very different now, sitting there with the sleeves of his sweatshirt pushed up and his hair askew, as if he had shed the persona he’d put on for class a couple of weeks before, and was somehow relieved to be himself, like an actor off-stage.

“I suppose it’s because it’s either very good or very bad,” she said.

He laughed. “A fair guess. But actually, not quite either.”

Then he leaned forward. “Listen, what I’m about to suggest may not appeal. It’s entirely up to you.”

Lorna stared at him. Was he going to verbally proposition her? She knew he had a reputation, perhaps she would admit there was some undertow of attraction between them… but this was so, eye-wateringly, direct.

“This,” he said, picking up her essay, “is messy and a little garbled in its argument. It lacks rigour. But…” he hesitated, “there’s something very special there, too. Something that made me sit up straight when I was reading it. It was clear you weren’t borrowing or repurposing ideas. That it came from a person who thinks differently, who makes connections that don’t occur to other people. It even made me… I don’t mind telling you…” he smiled, tapping the essay against the side of his desk, “a little envious.”

She blinked at him, still not sure what to say. Of course this all sounded like flattery. If what the Third Years at the bar had said was true, Dr Chase was looking for a new affair. She knew he was married, that his wife worked at another university, that he had a reputation, that – the clue was in his nickname – he was known to have affairs. But she knew, also, that he was telling the truth.

The pathway she’d found through the Sonnets had come to her in the middle of the night, almost in a dream state. And it had struck her as so obvious, so clear, that although she’d already written the essay, was supposed to submit it by that morning, she stayed up well into the wee hours hammering out a new version, typing up the last words as a pink dawn began to creep around the edges of the blind.

“Many people would say that having worked furiously hard to get into this university you’re better off taking a step back now from academia, using the next three years to become more rounded in preparation for life. All the extra-curricular stuff. The socialising. Work out who you really are.” He pushed a hand through his hair. “But if you want to really go the whole way, challenge that brain of yours to the max, get the top First. Well, I can help.” He smiled. Put the essay down on the coffee table between them, like a contract. “And I’m not talking about cheating.”

Lorna had weighed it all up then. The odd, perverse attraction she felt for him; what she wanted; how he could help her, what the trade was. Her eyes dropped to his left hand resting on his knee. The splayed strong fingers, the thin gold wedding band. Then looked back up at him directly.

“Who says there’s anything wrong with cheating?”

* * *

She flicked through the pile of paperwork on his desk. She wasn’t looking for anything specific, but that same sense of disquiet, the kind of itch you feel when you wake up knowing you’ve had some bad news but you can’t remember what, drove a desire to pick at something, to cross a line. Going through his stuff was a taboo, he was touchy about his work.

Mostly it was essays, some marked, some not. She scanned the printed pages, looking for his marks. The tiny ticks that meant he was pleased, little phrases “More here”, “unpack”, “Think harder!” written in the margins. The comments at the end that were either bland or sharp. A short burst of triumph when she found an essay by Alicia Evans and read his conclusion: “B(+) Too much paraphrasing of other people’s ideas. Look more closely at the primary text and come up with your own opinions.”

Perhaps he wasn’t as fickle as she suspected. Perhaps she was the less trustworthy one.

More printouts that she recognised from her own first-year tutorials. Christ, he must get bored cranking himself up every year to give the same lessons. No wonder he needed to find his excitement elsewhere. So that when she started reading a loose leaf and recognised her own work, a printed page from her Sonnets essay, her initial feeling was a flush of pleasure at the flow of language, the freshness of the idea.

He’d helped her rewrite it after their first meeting. They’d drunk a bottle of red wine as they talked it through, then started another. He’d taken her idea and they’d run with it until, giddy with booze and epiphanies she’d rewritten it, so that it was hers but better. Better than anything she had ever done. That was the night they’d ended up in bed.

And here it was on his desk, nearly a year later.

It was only when she fished around for the next page, looking for the same format, that she realised something was wrong. The layout was different. Bigger margins on the page. The footnotes in a tiny, professional-looking font she never used.

She hunted around, her hands growing clammy, before she found the title page. And an index, with twelve essay titles by different authors, all academics, including number 11:

“THE MASOCHISM OF DESIRE. ESCAPING THE SELF INSHAKESPEARE’S SONNETS” BY DR CHRISTOPHER CHASE.

Her essay. At a stretch, their essay. And stuck at the top, a note saying that galley proofs were to be confirmed by October 22nd.

More than a week ago.

* * *

The camera was still sitting on the desk where she’d left it last night. She picked up another photo that lay beside it, studied it for an instant and then slid it into the back pocket of her jeans. Looked around the room for the last time, then left the key on his desk, on top of her essay, and walked out, shutting the door behind her.

She took the longer route around the quad, stepping round the tip of the shadow from the sundial column, which had inched a fraction further along the paving stones.

At the porter’s lodge she asked if they had a spare envelope.

“Shouldn’t really,” said Greg, huffing a little behind his window. He was one of those round-faced, barrel-bellied late-middle-aged men who you could squint your eyes and imagine at seven years old, with fistfuls of stolen sweets in his pockets. “But go on then,” he said, handing her a brown envelope with a double seal, “just this once.”

“Which is the Dean’s pigeonhole?” asked Lorna.

“That one,” Greg told her, “or I can give it to him. We’ve got a college meeting after lunch.”

“Could you?” said Lorna, looking at the photo. “Good.”

She had taken it last night, after she’d destroyed the first one. Chris had been lightly snoring after she got back from the bathroom, in the deep rest of the satiated, so she lay down next to him, lay his left hand gently over her breast and, holding the polaroid as high as she could with the other hand, pressed the button. Even the flash hadn’t stirred him.

Not bad, she thought, standing at the porter’s lodge now, given the lack of light. Unmistakably him. Her, too, though this didn’t bother her. The college would never kick her out. They would fall on their knees, in fact. Do anything she wanted if she agreed to stay silent.

She placed it carefully into the envelope, sealed the flaps and wrote her name and number on the back.

Then she flashed Greg her biggest smile as she handed it over.

“Awfully kind of you. I’d love to make sure he gets it today.”

And then she walked out under the archway, onto the street where drifting piles of copper-coloured leaves lay thick on the pavements.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This story is a prequel to my novel, The Truants. It tells of one formative episode in the life of Lorna Clay, the English professor in The Truants, who proves to be the inspiration and dangerous obsession of a group of students in their first, easily corruptible year at a British university. In “1000 Ships”, Lorna is herself an undergraduate. I like to see it as her origin story, where we first see her meteoric talent, her attitude to truth, sex and power, and her appetite for misrule.

PYTHIA

OR, APOCALYPSE MAIDENS: PROPHECY AND OBSESSION AMONG THE DELPHIAN TECHNOMANTIC ELITE

Olivie Blake

Q: Ms. Thorn—

A: It’s Dr. Thorn.

Q: Of course, my apologies. Dr. Thorn, I am Lucas Girard, an attorney with Selden, Merriman, and Girard. I represent the defendant. This is a deposition, in which I will ask you questions and you must answer them truthfully. Although no judge is present, this is a formal legal proceeding, and you are under the same legal obligation to tell the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. Do you understand this?

A: I do.

Q: Excellent. Now, please don’t be uncomfortable. This is not a criminal proceeding. No one is being punished. We’d just like to understand what led to your involvement in the events of January 15th. And please remember that you will have the opportunity to read over this deposition and correct anything before it is presented in court.

A: I don’t anticipate making any mistakes, but thanks.

Q: It’s standard procedure to inform you, Doctor. Are you ready to begin?

A: Yes.

Q: Excellent. Please state your name, age, and occupation for the reporter.

A: Dr. Tai Thorn. I’m twenty-nine. And I’m a clinical psychologist.

Q: You’ve been practicing psychiatry for how long?

A: I haven’t.

Q: I’m sorry?

A: I don’t practice psychiatry. At the time I came to Delphi I had just finished my doctorate in psychology.

Q: I see. How long had you held your doctorate when you were invited to join the faculty at Delphi Institute of Technomancy?

A: Three months. And I wasn’t technically a member of the faculty – I had faculty privileges but I never taught any courses. I’m not a technomancer, just a normie.

Q: I see, thank you for clarifying. Does Delphi usually contract psychologists for their students?

A: No. Delphi is… not for people like me. Or you, I assume. I was initially surprised they hired a lawyer. Until I thought about it more, obviously, and then it made perfect sense. But at first I assumed everything was very, you know, confidential.

Q: I assure you I am very discreet.

A: Ha. Right. Well.

Q:How did you come to find Delphi, then? If they don’t normally require psychologists.

A: They found me. Will you also be speaking to Dr. Ellen Leith?

Q: I’m not at liberty to disclose that information at the moment, Dr. Thorn.

A: I’m just pointing out that I’m not the only anomaly involved. Ellen specializes in historical literature and she arrived the same day I did.

Q: If you don’t mind me backing up a bit, Dr. Thorn, three months with your completed degree seems quite… inexperienced, comparatively.

A: Oh, massively, yes. Ellen’s at the top of her field, so I could understand her being invited. Sort of. But from the day I arrived nobody felt I had a right to be there, which many of them made very clear to me on numerous occasions.

Q: Do you have any speculation now as to the nature of your employment?

A: Is that legally sound? The question, I mean. It feels, you know, leading.

Q: This is not a trial, Dr. Thorn. Merely exploratory questioning. I’d just like to know why you were invited to Delphi, if not to perform psychiatric services.

A: Oh, that’s not a mystery.

Q: No?

A: No. It’s extremely fucking— sorry, am I allowed to swear? Whatever, the point is it’s really simple. They sent for me because they had to.

Q: And why is that?

A:You do understand that Delphi is named after the oracle at Delphi for a reason, right? They’re essentially a cult that revolves around the magical supercomputer they built to tell the future.

Q: Meaning?

A: Meaning that what happened to Serena Li – which I assume is the reason we’re here – is the result of staggering collective delusion. Centuries of self-enforcing superstition. You know the quote from Einstein – “science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind”?

Q: I’m familiar, yes.

A: In the absence of actual faith – the kind that moves people to goodness, or at the very least to fear – Delphi had Pythia. If Pythia told every single one of those technomancers to swallow poison, they’d do it. If Pythia said burn it all to the ground, they would. If Pythia said okay, Serena Li, time to die—

Q: But as for the matter of your summons.

A: Aren’t you listening? Delphi hired me because Pythia told them to.

Q: That’s it?

A: Yes. That’s it.

* * *

Delphi only scouts from the top universities in the world, which is ironic because by nature no Delphian technomancers ever finish at university. Of everyone I met during my six months at Delphi, only Ellen and I had college degrees. Well, and Laurence. But he was unusual in a wide variety of ways.

Anyway, as I understand it, traditionally Delphians are tapped while they’re students at university – usually Oxford, Harvard, and MIT, plus Zurich, Munich, and a small battalion from universities in China, Singapore, and Hong Kong. For the record, Anglicized, my name sounds fittingly English. In person I was much more likely to be mistaken for one of the foreign-born students, even though I’d’ve been lucky to attend one of those schools. I went to a large, progressive public university in Los Angeles, which was a real stain on my character to some. Mostly Archambault, but occasionally also Laurence. Pythia of course didn’t mind.

Another irony is that Delphi is extremely slow to react to the times despite its obsession with technology and, more specifically, the future. Its members are traditionally tapped while in college because until the aughts, most technomancers would never have discovered their own proficiency unless they had the resources of a major university. Now a toddler can very easily operate an iPad. So, you know. The whole process could use some improvement I guess, or not. This is really not my area of expertise. In any case most students are twenty-one or twenty-two when they start, closer to thirty by the time they finish their technomancy training. Of course, just because they finish doesn’t mean they ever leave.

If I had to summarize the campus in a word, I think I’d use bucolic. No, stately. It’s very, very north, where people are quite mean, just as a matter of survival. The Puritanical quality of New England really runs deep, which to me feels emblematic of harsh winters. The campus is breathtakingly beautiful during the winter months much in the way gorgeous women are unapproachable and cold, though the way I first saw Delphi is how it’ll always be burned in my brain – that collegiate idyll of verdant vines and Gothic spires, autumnal foliage rustling on the whisper of a temperate breeze. Delphi’s campus is opulent enough, I imagine, to make the budding technomancer overlook its tempestuous sea of petty rivalries and tiresome affairs; the quiet carousing of a populace eternally in love with itself, all microdosing on Anglophilia and Adderall just to feel something. On the day I arrived, there had already been a recent death on campus, not that you’d catch the whiff of institutional rot by looking. The spires may cast a shadow but the ivy twines just the same.

I’ll warn you now that I have not an ounce of technomancy in me. I don’t have even a fraction of what Serena Li kept hidden up her sleeve, and certainly no more proficiency or knowledge than required to make my laptop work. I’m not convinced I’d be able to drive a Tesla, which to my knowledge is essentially one large computer. I’ve always had something of a glitch in me, which is why I specialize in cognitive behavioral therapy. I study people. Not machines.

But for Pythia, I made an exception.

The way technomancy works – from my perspective – is a mix of programming language, you know, binary and such, and a more arcane enchantment. Watching it was like watching a potion get made, where you could see the sparkle of magic or the ether or whatever it was pouring into the code itself, like honey from an open wound. The Olympias were especially graceful with their showmanship. They’d design the code in Python but then pause occasionally to input a rune (Greek, I think, in nature, because Delphi was nothing if not committed to aesthetic) that they’d then enchant into another river of code, like opening up a door or a vault or something. It was fascinating to watch, and visibly draining to the technomancer, who surrendered parts of themselves in the process. Later I’d realize just how easy it was, the conflagration of thought and blood to create some primal spark of sentience. I guess the less controversial word would be intelligence. But I’m feeling contradictory, so let’s call it life.

All the technomancers had tattoos – I’d noticed Laurence’s right away because he wore his sleeves rolled up and he was always agitated about something, usually me – but the Olympias had more of them. Serena in particular had runes that reached all the way up to her biceps, rivulets of tiny hieroglyphs that glowed while she typed. She kept her arms covered in public. Anecdotally, I’m told the student who died the year prior did the same, for what I presume were different reasons.

Laurence told me one night after the third or fourth time I said we should stop seeing each other that Pythia has existed in some form for over two hundred years, beginning with the Revolutionary War. Actually, the New Academy – which, if I haven’t already explained, is the academy within Delphi that’s devoted to keeping Pythia, well, alive – though again, that’s a controversial word to use, given everything – anyway, the New Academy was founded by the same Founding Fathers who wrote the Declaration of Independence and kept slaves. (Those facts aren’t related, I just like to put them next to each other.) The founders of Delphi were also Deists, which is kind of a cop-out theologically speaking. Though, I guess believing in a god who has omnipotence but chooses not to interfere explains how Delphi reconciled their knowledge that being chosen and being shitty weren’t mutually exclusive, or that misusing all that power would not be personally damning in any significant way. (Pythia seemed especially concerned with the nature of sin, but as I told her, real life is not often met with smiting or pillars of salt. Boys will be boys, and inevitably men will be men.)

In any case, Delphi wasn’t really what it is now until around World War I. The demand for cryptography as a military tactic is fairly well known, I imagine, and by the start of World War II, the algorithm known as Pythia had a whole specialty of technomancers dedicated solely to her maintenance. But it was only around the sixties that Pythia really became Pythia, which is a kind of forerunner to the internet as I understand it. Not our internet, of course, which is primarily used to track our habits and sell us things, but an internet whose job it was to know things purely for the sake of knowledge. That’s the crux of it, if you think about it. Technomancy, which is the magic part – cryptography is just the subset of technomancy aimed specifically at puzzles – is almost like necromancy. But instead of raising things from the dead, you raise them from nothing. And then you teach the nothing to know.

There are not many women at Delphi. Within five seconds of meeting Archambault I understood why. The professors and staff were mostly steep in age, with some younger-middle-age ones (like Benedict Masson, whose students called him Benedict, which in my professional opinion fell under the category of red flag) to strut around, liven up the place. When Ellen and I arrived, the number of live-in female staff doubled. The others were distant from my daily life; they lived in faculty housing while Ellen and I were given temporary apartments in the nicer student housing, where the year five and six technomancers lived. There were a handful of female students living there, arguably thriving. Some even made it all the way through the program. In their final year at Delphi were Elodie Hall, Nora Kaur, another one whose name I never caught. There had previously been two others, one who died mysteriously and one who less mysteriously absconded.

And Serena Li, who was the best of them. And the worst. But you already know about Serena.

* * *

Q: So you were brought in to help with Pythia, is that correct?

A: I was brought in because Pythia sent for me, but not initially to help. When I arrived Laurence was extremely, annoyingly blunt about the fact that I would not be doing anything without strict supervision.

Q: Laurence?

A: Sorry, Laurence Newland, the, uh… I guess he was a professor? No, more like a TA, I think. I don’t think he was faculty.

Q: Ah yes, Laurence Newland.

A: Is that a suspect list or just, like, a dramatis personae?

Q: I’m sorry?

A: That. The thing you just looked at to check for Laurence’s name. Is it a list of suspects?

Q: As I mentioned previously, this is not a trial, Dr. Thorn. Though to clarify your account, Laurence Newland is a student. He’s currently enrolled at Delphi.

A: Oh. So I was right, then.

Q: Hm?

A:He’s never leaving Delphi. Which is great to hear, honestly. Like, very fucked to hear, but also great. Liberating. Anyway, we were talking about Pythia, right? I didn’t meet her right away. I think Ellen’s expertise took precedence. Sorry, I mean Dr. Leith.

Q: What do you think Dr. Leith’s expertise was? In the context of Pythia.

A: Oh. God. Well, to explain that I’d have to explain Pythia.

Q: Okay, go ahead.

A: No, you misunderstand – I can’t actually explain Pythia. She’s… she’s a magical supercomputer, I guess, in layman’s terms. She was developed to chart sociopolitical trends and spot problems, and then to, like, shout if anything looked off. She was supposed to notice if North Korea was going to set off a missile or if Russia was choosing violence. Which Pythia definitely did notice! So. Even with everything going haywire she was still really good at her job, which is more than I can say for most of Delphi.

Q: And you believe Dr. Leith’s expertise was necessary in order to…?

A: Pythia was glitching. She had… not a virus. If Pythia’d had a virus… Well, that was the whole point of Ellen. Sorry – Dr. Leith. But anyway, Pythia was malfunctioning.

Q: How so?

A: She kept predicting apocalypses. Like, every day she’d predict the world was going to end by teatime or whatever. You can imagine this was a mess at first.

Q: Was it?

A: I don’t know, I wasn’t there. Laurence told me. But apparently all of Delphi genuinely thought the sky was falling because Pythia said so. I told you, right, that all of Delphi set their watch by her? But I mean that in like, an extreme, cult-fanatic kind of way. And so much had gone wrong over the past year, what with the affair and the suicide—

Q: I take it you mean the death of Lydia Liang?

A: I guess legally if that’s what I’m supposed to call it, then sure.

Q: The accusations of sexual misconduct to which I presume you are referring are a campus rumor that later proved insubstantial. And Miss Liang’s unfortunate death was an accident, as I believe you are aware.

A: Right, of course, like Serena Li’s death. Two female students in two years, probably not systemic, right? Don’t refute that, I’m aware that you can’t. Anyway the point is you can’t really blame Delphi, I guess, for the sense that everything was fated instead of just toxic. Anyway. Sorry. What was I saying?

Q: Pythia was glitching.

A: Right, so Archambault brought in Ellen because she specializes in demons.

Q: I’m sorry?

A: Where’d I lose you?

Q: Somewhere around demons. Didn’t you specify that the faculty at Delphi were largely atheist?

A: Oh of course, but still – these aren’t normal nerds, Luke. Can I call you Luke?

Q: Sure.

A: Great. These aren’t just regular scientists, Luke, they’re magic. They believe in the ineffable. They genuinely believe the universe knows they exist; that the universe blessed them individually with this power to create life itself. They are Pythia’s origin story. Pythia is also their religion. It’s very fucked up, honestly, and I say that as a mental health professional. There wasn’t a lot of time to get into that aspect of it because yeah, there’s just no time for that kind of foundational rewiring. The thing people always forget about a few bad apples is the part where they spoil the bunch. But the point is Ellen Leith is the leading researcher on Ancient Greek texts about demons, so they sent for her right away.

Q: You’re saying they thought Pythia had… a virus?

A: I’m saying they thought Pythia was possessed by a demon, but yeah, basically that’s my point. They couldn’t find a bug anywhere – and Laurence was adamant that if the almighty they couldn’t find the error in Pythia’s design, there wasn’t one – so they thought it must have been something worse. I’m not sure if the demon thing was literal but they were definitely looking for vengeful spirits, yeah. Partially out of fear. They’d never admit it, not really, but the idea of Pythia having any sort of illness was the only thing that really scared them – the closest thing to a god-fearing, mortal-soul kind of scare, which they otherwise weren’t capable of at an institutional scale. It’s that omnipotence thing, isn’t it? Bunch of creator-gods walking around, making and unmaking empires. Who cares if people get hurt, if their hearts break? Vindictive wrath was in short supply, but Pythia was worth a lot of money when she was working properly – hence the fear, because she could save the world. Or end it. So yeah, the empire thing still applies.

Anyway, like I said, I didn’t meet Pythia for a few weeks because Archambault hated me and wouldn’t let me anywhere near her beyond appeasing her requests. I don’t really know what he thought I was going to do to her. I mean, as far as supercomputers go she wasn’t technically worth stealing at that point. She got a lot right but the rest of it really confused them. Every day she said there would be blood, death, darkness, pestilence… it got hard to separate what was real and what wasn’t. They even brought in a priest.

Q: A priest?

A: Yeah, and a rabbi, and an imam… maybe others. Delphi didn’t have very good working knowledge of what is or isn’t an apocalypse. Like, how many locusts does it take to be considered a plague? How many firstborn sons have to die? Admittedly it’s a gray area.

Q: Okay, so to solve the Pythia problem they brought in a literature professor who specializes in demons, a bunch of religious leaders, and you.

A: Yep.

Q: Because Pythia asked for you.

A: Yep.

Q:Seems… odd.

A: That’s what Laurence said, too.

* * *

Let me be clear. I only slept with Laurence because I was bored. Not because Pythia told me to. RIP to Delphi but I’m different. Haha. Sorry. That’s kind of an internet joke. And anyway, Pythia did warn me that 97.3 percent of the scenarios she ran involved Laurence remaining at Delphi, which was again a very inhospitable environment for me given how they all considered my mere presence to be more threatening than any of the very real facts I presented to them. I don’t consider it a prophecy, Pythia’s warning. I mean, frankly, I already knew.

Pythia did have opinions, not just prophecies. Delphi didn’t think of them as opinions but I think I’ve already made it plenty clear that Delphi didn’t understand very much in general. This is what comes of defunding the arts, by the way. You get a lot of smart engineers who can’t understand when a magical supercomputer starts quoting Hamlet from a place of sarcasm.

Laurence was kind of like Pythia’s handler. Put simply: Laurence was a lot of magic, not a lot of sense. He was impressively foul-tempered, too, for someone who said “son of a gun” and “sweet mercy” where I might have gone for “fuckety goddamn fuck.” Still, whenever Laurence said anything, it was with a very clear undertone of motherfucker. He was not handsome. Closer to elegant, or maybe I misremember and he was just, you know, tall.

Pythia, however, was beautiful. The naming was not very clever – Pythia, the priestess, was inside Oracle Hall, which was palatial even for Delphi’s standards. The building was sort of conventional from the outside, predictable red brick with arches and pillars entwined in ivy, but with something of a balustrade around the exterior, more like a manor house than a university building. The inside had this vibrant, expensive Italianate tile, Venetian maybe. Chandeliers that dropped from cathedral-style ceilings. More arches. Sort of exactly the library you’d imagine would hold a magical oracle, only then you’d have to descend and things would get colder, the colors richer and more stark, like traversing Dante’s Inferno or a Vegas casino with the way the walls enveloped you, funneling you down until you lost track of the weather or time of day or what exactly you planned to do with your life prior to arriving. And gradually things got darker. More still. And then you could hear the whir of Pythia, like the quiet slumber of a tomb.

The best thing I can liken her to are the aqueducts in Córdoba. Cool stone, a long row of columns, ancient history, and an endless dark. In real life there were lights and such, but I’m talking about the feeling of being near her. Yes, ultimately she was just a room full of equipment, but being near her was contemplative, sacred. I know I talk a lot of shit but it really was like being in the room with God.

Laurence caught me talking to Pythia the first time. I hadn’t fully realized I was doing it. I went down there because I was curious, and because Ellen had told me she was pretty sure there wasn’t a demon involved but she was just a literature professor and really couldn’t know for sure (they should have asked a priest she joked but we both knew that wouldn’t be helpful, they’d already tried) and anyway, I don’t know, I think I just got tired of waiting. And Pythia let me bypass the alarms. I assume that’s what happened. Yeah, Pythia must have let me in the first time. Afterward it was Laurence. Notably once it was Serena Li. But the first time it was Pythia herself.

Do you know what it was that made her want me? It’s a funny story, actually. So, when I was in my third year of my psych program, I wrote this article for what was essentially our version of The Onion – you know, a satirical newspaper. My boyfriend at the time worked for the paper and asked me to write something – he was on deadline. He was always on deadline, it wasn’t a great way to live, I got tired of the whole thing not long after and I think he works one of the exciting journalism jobs now, the kind where people don’t really sleep and occasionally get shot. But I wrote an article called, um. Something like, “It’s the End of the World as We Know It and Your Anxiety is Just a Sign of the Times.” I’m like 50 percent positive it was snappier than that but that was the gist of it.

And anyway, yeah. That’s why Pythia called me. Because she’s basically magic internet, and with one exception – e.g., everything I’m telling you right now – nothing ever gets lost.

* * *

Q: So what was your diagnosis?

A: I wouldn’t say it was a diagnosis at the time. More of a hypothesis.

Q: Which was?

A: I was pretty certain Pythia had anxiety.

Q: Pythia the computer program?

A: