Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

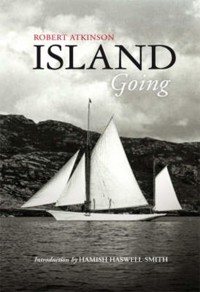

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

In July 1935, Robert Atkinson and John Ainslie set out on an ornithological search for the rare Leach's Fork-tailed Petrel. Their quest was to last for twelve years and took them from their Oxford base to many of the remote and often deserted islands off the north-west coast of Scotland. Island Going is the account of their adventure. Not only is it packed with marvellous descriptions of the wildlife and landscapes of the islands as well as the journey itself, it also paints a vivid portrait of the way of life of the islanders and their history and traditions.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 624

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Island Going

Island Going

Robert Atkinson

This edition first published in 2008 byBirlinn LtdWest Newington House10 Newington RoadEdinburghEH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Copyright © the Estate of Robert Atkinson

Introduction copyright © Hamish Haswell-Smith 2008

First published in 1949 by Collins

The moral right of Robert Atkinson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

ISBN13: 978 1 84158 712 7ISBN10: 1 84158 712 5

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is availablefrom the British Library

Typeset by Brinnoven, LivingstonPrinted and bound by Cox and Wyman Ltd, Reading

Author’s Note

I am grateful to too many of the kind people of the Hebrides to name all of them here; some are in this book and my indebtedness to them will be plain. But I must begin by saying a formal thank you to Kenneth MacIver of Stornoway, for the help and influence which so smoothed the way in prewar days; and for his great generosity since, without which Hebridean voyagings (still unexhausted) could hardly have been resumed.

A three-weeks’ stay on the island of St Kilda was with the generous permission of the owner, now Marquess of Bute. A later visit was with the assistance of James Fisher. The kindnesses of Alec MacFarquhar, grazing tenant of the island of North Rona, are unforgotten.

Certain facsimile illustrations are reproduced by permission of: the Editor, The Illustrated London News; the executors of the late Cherry Kearton; and the Controller of HM Stationery Office. Various quotations are printed by permission of: Malcolm Stewart; D.M. Reid and the publishers of The Cornhill Magazine; the executors of the late Richard Kearton; the Editor, the Stornoway Gazette; The Moray Press; Hugh MacDiarmid and B.T. Batsford, Ltd.; Messrs. Douglas and Foulis (extracts from J.A. Harvie-Brown’s Vertebrate Fauna of the Outer Hebrides).

R.A.

Contents

INTRODUCTION

PROLOGUE

The Outliers

FIRST YEAR

Handa Island

1 The Sailors’ Home

2 The First Island

SECOND YEAR

North Rona – Shiant Isles – Canna

3 North!

4 ‘A World Alone’

5 A House and Grounds

6 Leach’s Petrel

7 A Rona Annual

8 The Visitors’ Years

1 An Ecclesiological Note

2 Melancholy Events

3 Steam Yachts Downwards

9 A Dull Calm Night

10 The Shiant Isles

1 Eileanan Seunta, The Enchanted Isles

2 Garbh Eilean and Eilean an Tigh

11 A Shearwater Hunt

12 Rough Island-story

1 A Hundred Years of Decline

2 The Ancient Race

3 The Legend

THIRD YEAR

Flannan Isles – North Rona – Eigg

13 Rock Station

1 Eilean Mor

2 Flannans Might and Relief Day

14 Another Rona Annual

15 The Voice of Eigg

FOURTH YEAR

North Uist – Monach Isles – St Kilda

16 Sea-board, North Uist

17 The Monach Isles

18 Going to St Kilda

19 St Kilda Now

20 Sheep, Mice and Wrens

1 Sheep

2 Mice

3 Wrens

21 Natives and Visitors

22 St Kilda Evacuated

FIFTH YEAR

Sula Sgeir

23 Ultima Thule

24 Attempting Ultima Thule

25 ‘What can be said of it?’

26 The fishing boat Heather

LONG INTERVAL

Lewis Remembered

27 Lewis Remembered

SIXTH YEAR

The Hebrides Regained

28 A View of the Shiant Isles

29 A View of North Rona

Epilogue, A Bird’s-Eye View

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

EVENTS AND DATES, NORTH RONA

INDEX

Illustrations in the Text

1 Sketch Map of Handa

2 Shepherds’ Hut, Handa Island

3 Sketch Map of North Rona

4 Sketch Map of Shiant Isles

5 Sketch Map of Flannan Isles

6 Sketch Map of Monarch Isles

7 Sketch Map of St Kilda

Introduction

To be marooned on a desert island sounds romantic, but in real life would you truly want it to happen? And if the island had no luxuriant vegetation, no sandy beach, no coconut palm trees, no boat, no telephone, no radio, no means of escape and is surrounded by wild North Atlantic seas? I know what my answer would be.

Yet Robert Atkinson and his fellow naturalist John Ainslie, still only in their late teens and with no knowledge of the Scottish islands, decided that this was the only way for them to study the habits of a little-known bird called Leach’s fork-tailed petrel, which had been seen on the remote island of North Rona.

The habits of Leach’s fork-tailed petrel is not the sort of subject which would set the average reader’s heart alight. The bird should really have been called Bullock’s fork-tailed petrel because the first known specimen was brought back from the island of Soay in the St Kilda group in 1818 by a Mr Bullock, ornithologist. But this specimen was later acquired by the British Museum and the curator, Dr Leach, decided to name it after himself. The bird was known to live in holes in the ground, make strange noises at night and have mainly nocturnal habits – and that was it. Not much to go on, but enough to arouse the avid curiosity of two young naturalists.

It was 1935. Based in Oxford and with very limited resources Atkinson and Ainslie set off for the unknown north. Eventually they reached Rona after many false beginnings and dead ends. They spent about a month on the island in fairly persistent rain, sheltered under a ‘rickcloth’ in the prehistoric depression in the ground called the ‘manse’. Pause for a moment and put yourself in their shoes. You have limited food supplies, very poor and exposed accommodation, a lot of dreadfully bad weather, and you are alone on a small northern island which is very rarely visited by anyone. No boat is expected for at least three or four weeks. On a fine clear day it is just possible to see the Butt of Lewis on the horizon and, sometimes, a faint glimpse of the mainland mountains, but most of the time the isolation is complete. What a wonderful example this is of sheer youthful enthusiasm and scientific endeavour.

There was a time when one could count the writers of books about the Scottish islands on the fingers of one hand. The islands were an unknown territory, virtually right on the edge of the civilised world. They had appeared vaguely on ancient maps and had been visited and settled by a few brave Neolithic wanderers after the Ice Age and later by Celtic monks and Norse marauders, but as far as the rest of the world was concerned they hardly existed.

The first attempt to classify this oceanic extremity was made by Dean Sir Donald Munro in 1549 as he was interested in recording the extent of his ecclesiastical domain. But as his scanty notes were not published until 1774 his findings were of little value to the general public. It was Martin Martin in 1703 who was the first to put this extensive area of the British Isles on the map with his best-seller entitled, A Description of the Western Isles of Scotland containing . . . followed by a very lengthy list of every conceivable item of interest including – Second Sight, Curing of Diseases, & Dangerous Rocks . . . His book, in turn, encouraged other notable 18th-century figures to explore this strange territory such as Thomas Pennant in 1772 and that inimitable duo, Boswell and Johnson, in 1775.

In the 19th century others followed, including William Daniell with his beautiful drawings and aquatints, Ordnance Survey cartographers doing their best to record the Gaelic place-names, Dr John Macculloch the geologist, T.S. Muir, some keen amateur scientists such as J.A. Harvie-Brown, yachtsman and naturalist, and members of the Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments.

Most of these visitors published details of their visits but always in suitably sober terms.

It was Robert Atkinson, just before the middle of the twentieth century, who created an invigorating new genre in island writing. This young man succeeded in translating all his enthusiasm, experiences, and love of these islands into an account which, for me, is a classic of its type. Brought up in the south of England and a total stranger to the ways of the windblown north you can sense his growing attachment to every aspect of island life and his respect and admiration of the islanders. At the same time a gentle sense of humour runs through the entire narrative rather as one can have a chuckle at the demeanour of a much-loved elderly relative.

Atkinson obviously had a cast-iron stomach whereas his fellow-naturalist John Ainslie suffered badly from sea-sickness. They used various types of craft to reach the islands and as anyone who has sailed among the islands knows the sea is usually bouncy and occasionally positively tumultuous. In the end poor John Ainslie could take no more and scurried back to southern pastures. As is often the case with the hardened salt I suspect that Atkinson had little sympathy for his friend’s suffering. Nelson would have been more understanding as he too suffered from seasickness – which is my vain excuse when anyone seems surprised that I too at times feel distinctly queasy when at sea.

After his sojourn on North Rona it is clear that Atkinson had become addicted to the islands. Yes, the study of what used to be called natural history was always his prime reason for going there but at times one wonders if it was actually an excuse. He kept wanting to land on and explore yet another lonely island. Anyone who loves what I call ‘islandeering’ will understand this desire. His soul had been captivated by the essence of the islands. He had previously been on Handa, but he went on to spend time on the Shiant Isles, Canna, the Flannan Isles, Eigg, North Uist, the Monach Isles, Shillay, and the lonely Atlantic outpost of Sula Sgeir.

St Kilda, the dream destination of so many, inevitably caught his fancy. It was only a few years since the St Kildans had been evacuated and some were still returning to spend a few nostalgic summer months there. So many of the everyday items of life as we know them had passed them by. The Government had generously provided them with forestry work and housing at Loch Aline on the mainland and yet they had never before seen a tree – or a staircase. They had little knowledge of money and many of them could speak no English. In other words, they were deposited on the mainland utterly unprepared for a completely different life. It says a lot for their resilience that they managed to survive the trauma.

So Atkinson was lucky to spend three weeks on Hirta, the principal island; to meet a few of them in their home environment; and to be able to see and describe at first-hand this last vestige of a disappearing way of life. His description of the island and of the islanders themselves is superb, sparing nothing but also full of sensitivity and understanding.

I can remember my utter excitement when we first sailed to the St Kilda archipelago on a summer’s day and dropped anchor just as the sun was setting over Village Bay. In the morning we landed at the crack of dawn and dragged the long-suffering National Trust warden out of bed in his pyjamas to register our presence on the island. As the sunlight spread down Connachair the whole lonely splendour of the place struck home. It was overwhelming. A Stone Age landscape in the modern age.

But St Kilda is civilised in comparison to Sula Sgeir, that lonely barren rock far out in the sea to the west of Rona. Legend has it that St Ronan’s sister, Brianuille or Brenhilda, lived with the saint on Rona until one day he admired her beautiful legs. ‘Time to leave,’ she said, and sailed to Sula Sgeir where she eventually died in solitude. House-keeping must have been a problem for her. Atkinson and Ainslie avoided entering the primitive beehive sheilings perched high above the waves as they were deep in smelly manure and dead birds. Instead they spent the night outside while Atkinson photographed the fork-tailed petrels.

One can hardly discuss Robert Atkinson’s work without mentioning his remarkable photography. Although by present day standards his equipment was primitive and heavy, and he sometimes mislaid his flashbulbs, the photographs published here are a unique and wonderful record of the islands and their wildlife. In 1951 Atkinson published a series of beautiful full-colour photographs of British orchids and in 1980, still obviously bitten by the island bug, he published another equally-readable book recording his seal-watching experiences on the tiny island of Shillay in the Sound of Harris. But in my opinion this book, Island Going, so full of youthful enthusiasm and a sense of discovery, remains his greatest legacy.

Hamish Haswell-SmithJuly 2008

At first it seem’d a little speck,

And then it seemed a mist . . .

A speck, a mist, a shape, I wist!

And still it near’d and near’d . . .

PROLOGUE

The Outliers

A small unheard-of sea-bird, chance-found in the index of a bird book, was called – Leach’s Fork-tailed Petrel. It sounded like a true ornithologists’ child, cumbrously museum-named, and not far removed from the class of lesser yellow-bellied fire-eater. It was just what we were looking for, in January or February of 1935.

The only known European stations are in the British Isles – on St Kilda, the Flannans, North Rona, and a few islands off the west coast of Ireland.

Admirable! Leach’s petrel was allied to the much more familiar storm petrel, ‘Mother Carey’s Chicken’, whose habits its own appeared to resemble, but ‘Information is scanty.’ We, John Ainslie and myself, soon had Oceanodroma leucorrhoa leucorrhoa on a short list. We wanted some far place and outlandish, little known bird; we wished to join the searchers after rarity, who went on expeditions to skim the cream from new places.

The Flannan Isles were disqualified by a lighthouse; St Kilda was well known and long ago the Kearton brothers had taken their pioneering camera there, followed by very many others. We had never heard of North Rona before, but the tiny island seemed sufficiently remote and inaccessible when we found it marked as a dot some forty miles to seaward from Cape Wrath, the very north-westward corner of Scotland. We plumped for Rona and Leach’s petrel. The next land beyond was the Faroes, and then Iceland. It did seem a thing that in Britain there should be ground, a decent-sized desert island, where you would be parted from the nearest other Man by forty miles of grey northern sea – this was something to imagine from the south of England. But how on earth to get to North Rona and what was to be found behind the name?

Gradually during the early months of 1935 we came to find out a little about the history and resources of the island. It lay roughly equidistant from the lighthouses of Cape Wrath and Butt of Lewis, pertaining to the Outer Hebrides but making, along with St Kilda and the Flannans, a line of ultimate outliers from twenty to forty miles beyond them. The island was a bare grassy hump, about 350 feet at its best elevation and of about 300 acres extent. Once it had had its own natives, ‘a skiff their navy, and a rock their wealth,’ but for nearly a hundred years now it had lain uninhabited and deserted. There were the remains of a village, derelict overgrown stones; this was where the Leach’s petrels were found. Some sort of hermit, whether of history or mythology, had built a cell there in the Dark Ages. A flock of gone-wild sheep roamed over the island. The coast was entirely rock-bound with no beach of any sort; landing was ‘difficult’.

How to make a start, with Rona empty and far away and the people and resources of the north-west corner of its parent Scotland foreign and unknown? We wrote to any one we could think of who might conceivably know something of Rona and of a way of getting there, to harbour-masters, lighthouse-keepers, yachtsmen, fishermen, trawler owners, curators of museums, naturalists. The stamped addressed envelopes came back with kindly but unadvancing replies until between us we had a sheaf of contradictory information, suggestion and bafflement:

It is so many years ago (1894) that I visited North Rona that I do not know in the least the present circumstances. I was becalmed in my yacht in the neighbourhood of the island when returning to Stornoway from the Faroes . . . I have no note of seeing any fork-tailed petrels. At that time the island was uninhabited . . . The weather of course would be a great gamble.

Or this:

I have just received your letter re information about the Island of North Rona but I’m sorry I cannot give you very much. North Rona belongs to Lewis and the crofters about the Port of Ness have sheep grazing on it and I understand they usually go out to clip their sheep either this month or next month. I expect some of them will have motor boats now. You will have to go either to Mallaig or Kyle of Lochalsh to get a steamer for Stornoway and then Motor Bus to the Port of Ness. I would advise you to communicate with The Principle Lightkeeper, Butt of Lewis Lighthouse, Port of Ness, Stornoway, Scotland.

‘Just a short note along with the information about North Rona,’ wrote the Principal Lightkeeper from the Butt of Lewis.

A Drifter is leaving here at the end of June or early in July, to go out for sheep. They will probably be ashore for 12 hours or so. A. MacFarquhar, Mill House, Dell, Ness, Lewis, rents the place, and he arranges for the time of sailing, as the sheep belong to him. If this will suit you, communicate with him, and I have no doubt he will be pleased to take you. Another alternative route would be via Aberdeen, if any trawlers from that port were using the Rona ground . . . Then the Fishery Cruiser often goes out there; and if you communicate with the Secretary, Fishery Board, Edinburgh, and state your requirements, he may land you and call again for you later in the season. I am afraid these are the only routes to get to North Rona. I hope some of the routes will suit you . . . This is all the information I can gather meantime so will close hoping you will manage to get a landing.

This helpful letter turned out to be largely accurate but unfortunately neither drifter nor trawler (not that we knew the difference between them) would do. Hours or days on North Rona were no use, we wanted weeks on the island to investigate the nocturnal, subterranean and probably obscure habits of our chosen petrel. The drifter for the sheep went for only one day once a year. There was a vague possibility of chartering a Stornoway drifter but at such immense cost it was out of the question. And even if an east coast trawler rounding the north of Scotland to the Atlantic fishing grounds should land us on her outward trip, we would have to return on her homeward voyage within a few days; or be stranded. We were much too unofficial for the Fishery Board.

At this stage – ‘Dear John, Somebody’s even written a book about Rona, did you ever – I’ve just been sent a copy. Very exciting but actually it doesn’t get us much forrarder,’ etc., etc. The book was Malcolm Stewart’s invaluable Ronay, describing Rona, its companion rock Sula Sgeir and also the Flannan Islands. The author had been an undergraduate reading geology at Oxford, and during the long vacations of 1930 and 1931 had twice managed to get a landing on North Rona. He had pieced together old travellers’ accounts and quoted from them in a handbook which would surely be ever blessed by hopeful followers to these isles, which, so he claimed, ‘have even disappeared from the modern map of Scotland.’ His first visit had been with D.M. Reid, science master at Harrow, his second with T.H. Harrisson. They had worked the east coast route by trawler from Aberdeen:

With the cold grey light of breaking dawn land was clearly discernible some few miles off the starboard bow . . . As the ship approached, so the land grew and grew until it was easily possible to make out the shape of the island . . .

The thrill that Fig. 2 communicated! – a fuzzy snapshot of ‘North Rona from the East,’ a choppy sea and a dark hump of land across the horizon. Or Fig. 3, ‘The S.W. Extremity from the Village,’ some heaps of overgrown stones and a coast sprawling into mist beyond.

A boat was lowered. Though so easily said, this operation required many minutes to perform, since it had not been lowered in many years, a point of honour amongst trawlermen. The best place for getting ashore appeared to be in a small inlet towards the centre of the cast side. But even here landing was by no means easy, for the swell lifted and lowered the small boat ceaselessly. A quick jump ashore while the boat rose and a desperate grab at the rock was the only possible course to adopt, while the gear had to be thrown ashore piecemeal . . .

As the trawler steamed on its way two men were left over forty miles from the nearest soul, with a great expanse of sea between, but with an unknown island at their feet to explore. (Ronay, 1933)

‘Our Loneliest Isle’ by D.M. Reid in the Cornhill Magazine for September, 1931 (which we turned up) also described that visit. Leach’s fork-tailed petrels were there all right.

This scourge lives in burrows in the roofs of the houses and remains quiet all day. Once you have got yourself comfortably tucked in for the night and have at last really got to sleep, these birds begin to take a hand in things. First of all they sit round in a circle and talk to each other in an extremely loud voice which sounds something like this – Pui-e-e-e brrrrrrrrr – the later part like a very bad and very prolonged gear-change. This ultimately, after a series of nightmares, wakes you up. While you are still trying to adjust your ideas to account for it all, something walks unhurriedly across your face and reaching your forehead says ‘Pui-e-e brrrr——’ and all your returning senses fly to pieces and you make a wild grab and catch nothing. And so the night goes on.

But our own prospects of reaching Rona seemed increasingly remote. ‘I have to confess that you have set me a difficult job!’ wrote D.M. Reid himself. ‘It used to be easy to get from Aberdeen on a trawler to N. Rona. That method, however, is no longer possible . . .’

‘I was lucky enough to have the loan of my father’s yacht when I was on N. Ronay,’ wrote A.B. Duncan whom we had traced as a visitor in July, 1929. The last word did seem to be yacht, but indeed whose? And who would not only land us but come back to take us off a month or so later? Time was getting short; correspondence certainly pointed out the difficulties but could not solve the problem. ‘Years had passed in vain attempts, and still we had not reached North Rona,’ wrote a visitor of a hundred and more years before; ‘nothing seemed to have been attained while that remained to be done.’ We too began to think of trying again next year. Perhaps this summer we could at least discover some base from which Rona could be reached, and then knowing more of the circumstances could make plans for a year ahead.

It was already well into July when we met D.M. Reid in person. We had to agree when he could only suggest as alternative the north-west corner of the mainland. Some off-lying isles there with queer names were little known and would be worth looking into. He himself kept a boat up there, his boatman might be able to take us out. At least Sutherland was the nearest mainland to Rona. Possibly there might be some sizable fishing boats thereabouts. And once from the tower of Cape Wrath lighthouse Malcolm Stewart had made out an ultimate speck on the horizon. ‘For all the accuracy of the map can this be land?’ he had asked. North Rona seen from the mainland!

Some unsuspected isle in the far seas

Some unsuspected isle in far-off seas

First Year

HANDA ISLAND

1935

1

The Sailors Home

In his mother’s car, on July 25th, 1935, John Ainslie and myself set out from Oxfordshire for the north-west corner of Sutherland. It was a fine morning with heat to come, and when that was over, and the day nearly gone, the hills of Lanark gave back the afterglow of sunset, the whitewashed walls of cottages were pink and old dead grass was the colour of flowering heather. At half-past one next morning when the speedometer showed 500 miles, we pulled off the road on to the edge of a bleak, anonymous moor and slept in the front seats until grouse began to call and the light came again. We pushed on north and west all day, by Inverness, Invergordon and Lairg until the tar ended, the road became single track, and we entered the sodden grandeur of the west.

Fifty miles beyond Lairg the road reached the coast at a little township called Kinloch Bervie, though it had already met miles inland the head-waters of the great sea lochs. The ribbon that unwound from London in July sun petered out into rain-swept moorland two or three miles beyond Kinloch Bervie. Another fifteen or so miles of uninhabited, trackless moor and the cliffs turned the north-west corner of Scotland at Cape Wrath.

It had been raining for a week, said the old lady at the post office. We should find a hotel, a petrol pump and a shop farther on. Rain sluiced off the corrugated iron roofs of the houses. After day, night, and day again of motor-car buzz, it was good to soak in a hot bath in the small fishing hotel, which was full of anglers and fish.

A few weeks before, a timber loaded steamer had sprung a leak off Cape Wrath and had ‘by grace and favour,’ said the gentle proprietor of the hotel, managed to reach Loch Inchard and take the beach. He had put up the crew in an empty cottage against the loch while they had stopped the leak and refloated their ship. They had left behind a large signboard inscribed ‘Sailors’ Home.’ We were welcome, me dear boys, to the use of the cottage for ten shillings, said kind Mr Macleod. We moved in straight away, pulled some bracken from the hillside for bedding and got a peat fire going. The watcher, a young phlegmatic Highlander who was employed to keep poachers off the hotel water, was already using the cottage.

The Sailors’ Home would have made such a perfect base for North Rona! If only there had been a few fishing vessels about. So there had been, once, but not now, nor likely to be with the nearest railway fifty miles away at Lairg. The wooden pier of Kinloch Bervie stood empty and open to the west. The boatman of D.M. Reid whom we found at Rhiconich at the head of the loch, was kindly, but most of the boat’s engine was away being repaired. Stornoway was the one and only place; there were plenty of drifters there and a big fishing industry. Of the islands with queer names there was particularly Am Balg, Bulgie Island, on the way towards Cape Wrath. It had a good landing place, the boatman said he would have been pleased to have taken us out.

We looked out to green-topped Bulgie Island when we walked over the moor to Sandwood Bay on the way towards Cape Wrath. Its steep cliffs were skirted with white water, to seaward and windward by a mile or more of grey, heaving rollers; it was not, after all, to be landed upon. Between stinging flurries of rain, Cape Wrath lighthouse just showed to the north. The solitary deserted cottage by Sandwood Loch had a corrugated iron roof and under it, a bath. Five trackless miles of stones and oozing peat separated the cottage from the road-end. One day perhaps the bath would be retrieved across the moor.

In the Sailors’ Home the watcher sat large and slow before the old iron kitchen range which, apart from his chair, was the only furniture. His present job suited him fine, he said, puffing at a pipe of the treacly black twist. It was easy living about there, no unemployed. Glasgow-baked wrapped bread came once a week from Lairg. The mail van did the fifty miles to Lairg every evening and brought back the newspapers. The watcher complained that the pollis – there was a policeman at Rhiconich – now insisted that motor bikes be licensed.

The life of the district appeared to centre on the hotel. Its fishing made employment, and its newly built bar recreation. Contemporary manners were fast finding a way to these townships of Loch Inchard, though the nearest cinema was still in Lairg. There were half a dozen wireless sets in the district. The newer houses were identical, built of corrugated iron and match-boarding, their roofs secured against the wind by wires spanning the ridges and dangling at the eaves with boulders.

Boswell: These stones hang round the bottom of the roof, and make it look like a lady’s hair in papers; but I should think that, when there is wind, they would come down and knock people on the head.

The sustenance of the scattered houses was not obvious. A few potato patches, some scraggy hens and cows seemed hardly adequate. One or two locked wooden huts turned out to be shops; local knowledge was required to discover when they would open. But housekeeping in the Sailors’ Home was easy enough: water from a burn a hundred yards along the road, milk and eggs from a nearby croft which also conducted a hut-shop, a sack or two of peat for the carrying. A pity it could not have been the Rona roadhead.

But if it was sea-birds we wanted, Mr Reid’s boatman had said, Handa Island was the place, down the coast off Scourie. All the sea-birds under the sun nested there. The watcher told us he had once spent nine weeks there himself, watching the sheep. At least it was an island.

Handa and its sea-fowl were evidently a show-piece for the fishing hotel at Scourie. And the hotel seemed also to have a monopoly of the place when we found, taking high tea among the stuffed eagles, wild cats and enormous fish, that the proprietor owned the motor boat; the price was high, and the boatmen were engaged as gillies. Some fishermen at a little place up the coast called Tarbet, directly opposite Handa, might make an alternative. The switchback road over uninhabited country turned out to be nearly impassable, but it ended at the door of a genial old crofter who knew all about Handa; his grandfather had been born there. A mile of foot track led on and down to a strip of beach with two or three heavy rowing boats drawn up, and two or three crofts standing back from the sea; this was the euphemistically named Port of Tarbet. The island lay out in the evening sun, a long dark hump across the sea. We arranged to be rowed there the following day.

Next day we landed at the sheltered eastern corner of Handa and stepped out across the width of the island; the boatmen would come and fetch us in the evening. The bird cliffs were on the seaward side. There the flat top of the island was cut off suddenly into cliff walls nearly 300 feet deep. Back from the cliff edge the ground fell away gradually to the southward by rough grass and heather to rabbity dunes and a shore of reef and sand. The island was empty but for sheep. The birds were sounding long before we reached the cliff edge; then, peering over, the void below was a snowstorm of flying sea-fowl. The noise struck like a blast. It was new, all new, a first introduction for both of us to the welter of a big scale sea-cliff colony.

The Handa cliffs being of a rusty-looking sandstone, stratified in nearly horizontal beds, had eroded into tier upon tier of shelves and balconies, all now packed with vociferous fowl. All the common cliff colonists were here, each making a noise after its own kind – puffins, razorbills, guillemots, kittiwakes, shags, fulmars, herring and black-backed gulls, in numbers great or less. Straight below us was a small bay enclosed by cliffs but accessible at the head by precipitous broken slopes strewn with boulders and covered with a mat of bird-dunged chickweed. We called it Puffin Bay.

Some of the birds were strangers; we had never before set eyes on the extraordinary puffin or the inscrutable fulmar. So brand new was this unique first sight of puffins at the edge of Handa, they might have been of fresh creation: bright fantastic dolls – but alive! They sat about the broken slopes, seeming alone of all the hordes to have time to do nothing. Their earthbound breeding season was ending. They stood or sat, yawned or leapt overboard with whirring wings, top-heavy beaks hanging downwards, orange webbed feet spread fanwise behind. Surely familiarity could never stale the real oddness of a puffin. Most birds are not at all comic, but puffins from the beginning were funny of themselves, as domestic ducks are. When Doctor John Macculloch in his time – he for whom ‘years had passed in vain attempts’ to reach North Rona – sailed past Handa he thought the puffins and auks ‘most ornamental’; the long ranks of brilliant white breasts resembled edgings of daisies or rows of snowdrops. The mate fired a musket at them and the cloud of birds arising ‘looked as if a feather bed had been opened and shook in the breeze.’

We clambered down a sheep track to the floor of Puffin Bay, where flat rock skirted the cliff base. Shags were nesting among piled-up boulders in a stench of decomposed fish and exclusive shag reek. The sites of their noisome dens were shown by the whitewash of young and old. The black adult birds flapped away making guttural noises, the young scrabbled into far recesses, defaecating over each other as they went, then facing about and trying to bring up. The stinking nests showed all stages from eggs and newly hatched, perfectly naked, coal-black nestlings to full-sized young.

Shags leaving their perches in a fright dived straight underwater; the necks popped up well out to sea and twisted every way in curiosity. A shag coming in to land was good to watch. It would finish off with a few violent wing-beats, and as often as not, fall flat on its front as its own uncontrollable momentum carried it on; pick itself up, shake the tail, waddle forward, surely trying to look as though nothing had happened. I peered into a small cavern and saw a shag before it saw me: fast asleep, head under wing, standing on its flat feet. A bird like a shag, fascinating but not inviting sympathy, could be seen for what it nearly is: a warmed-up reptile with feathers. Some hardy fishermen could still eat a cooked shag.

The cliff base was littered with eggshells of razorbills and guillemots and with young birds, alive, dead and half-eaten; casualties from the roaring nurseries above. Yet the wastage was nothing to the careless seething overhead. The guillemot slums were crowded tier on tier, thus the pools of egg-yolk here below. No carefulness in the breeding of guillemots, none of the neat nests or quiet brooding of inland birds. They went headlong at the business, a-jabbering and a-rowing, knocking each other’s eggs over the edge. They stuffed something down the offsprings’ gullets, paddled about in the muck, whirred away to sea for more. They cared nothing for each other’s excreta. On Handa only the puffins had time to stand and stare.

Kittiwakes’ onomatopoeic cries increased the clamour. One huge piece of cliff, overhung like half the dome of a cathedral, was plastered with kittiwakes’ seaweed nests, so that one could not go unsplashed below. The dank dripping place echoed with their screeches; a kittiwake seen silent for a moment, standing neat and gentle beside its young, looked incapable of making such a row.

The fulmars’ nesting was withdrawn and quieter and took place on exclusive, earthy ledges where the cliff was soft and green grown. The gulls hawked to and fro before the cliff; they had finished their breeding though they still kept one or two special promontories.

All day the tumult went on, the birds whizzed to and from their ledges, crannies and holes. We scrambled where we could and held in our hands young kittiwakes, guillemots and razorbills and drew out for a look a young puffin or two huddled at burrow’s end. In the evening the boatmen came out again and we returned northwards to the Sailors’ Home. There had been time to see only a little of the cliffs, nothing of the rest of the island. We should come back in a day or two and take up residence.

2

The First Island

The large but minimum pile of bedding, food and etceteras lately heaped on the rotting wooden floor of the Sailors’ Home, now lay dumped on the stone slabs of the shepherds’ hut, Handa Island, transported thither by road, by our aching backs along the mile of track to Port of Tarbet, and by rowing boat. The hut stood inland and solitary, a low stone box with walls a couple of feet thick, a corrugated iron roof slung with boulders and a single door giving on to the mainland. This hut, the sheep, a dipping-trough and enclosure were the marks of contemporary human use of Handa. Two shepherds came and lived in the hut during the lambing season and again in late summer for the dipping, said the fishermen. Otherwise Handa had long been uninhabited. The father of one of the fishermen had been born in the island.

We mentioned some diffidence about moving in without even asking; would it be all right? The fishermen thought such doubts unreasonable and delighted in showing off the unexpected resources; they were as pleased as children. Then their figures diminished down the slope to the Sound, leaving ourselves to five days of undisturbed possession (we hoped).

The hut stood on a slope with rising ground of bracken and rocks behind and the stone-walled sheep-pen to one side. A patch of bog delivered a tiny burn nearby whose trickle was diverted into an aqueduct of two boards nailed together and finished with a corned beef tin for a spout. It was dim inside after the outdoor seaside glare, though the hut was not at all the rude bothy we had expected. It was divided inside by a string hung with the stock of blackened bedding things: the near end by the door stacked to the roof with wooden sheep-troughs, peat, peat digging tools, rabbit wires and indigenous junk – oddments found and kept in case they should come in useful, such as an old electric light bulb; the far end beyond the blankets was furnished and had a fireplace in the end wall. We had intended to do without fire or cooking. The heads of the two beds were ranged on either side of the fireplace, one bedstead of old iron with a mesh mattress, the other of deal, without. This second bed (mine) was peculiar in having only three narrow boards to bridge the space it enclosed, one each for head, hips and feet. Above the beds were cuttings from Punch in driftwood frames. Punch? – of course, old copies from the Scourie hotel. A sausage-maker’s coloured calendar was for the current year but had not been torn off for four months. There had been a good deal of bad weather, judging by the amount of poker-work on the wooden bed. ‘A happy home’ was carved on the door, and ‘Old Dan’ had been here for five years running.

The rest of the furniture was a wooden table and an iron armchair with only the iron parts left. Mainland rubbish, rather than be thrown away, could usefully go to Handa.

Such light as there was indoors got in through two tiny windows and through a jagged hole in the roof made, so the fishermen had said, by the unexpected going off of a shepherd’s muzzle loader. The chimney was topped with a bottomless bucket, wired on, upside down. The flue was simply a hole left in the middle of the wall; later on the view down it to the glowing peat at the bottom was cosy enough.

We shut the door behind us and walked right round the four or five miles of coastline of our first uninhabited island. It fell far short of an ideal. A broadly oval island used by birds and sheep, limited by cliffs round the seaward side, sloping to a reefed shore facing the mainland; nothing else. The interior was undifferentiated, a broad back of very rough grazing with boulders sticking out of it and two or three boggy little lochs. The old inhabitants had left only some inconspicuous nettle-grown walls and a few gravestones down by the shore. No sheltered indents of coastline into calm water, no detail of warm dell or little valley, no purling stream or plashing waterfall, no kind of tree or shrub, no flowers. The tallest vegetation was bracken. A little driftwood and a diminishing few leathery mushrooms were the resources. But we were the only inhabitants. A cold wind blowing in from the sea laid over the yellowed sedges and waved the tufts of cotton grass. The boggy little lochs were chill and grey. It was autumn already, in the first days of August. Barren wildness had to be the attraction of the Scottish islands, or there was nothing?

Fig 1. Sketch map of Handa

Where would the world be, once bereftOf wet and wildness . . .?

It put such value on one’s shelter. We were soon enjoying sitting by the fire in the hut while rain rattled on the iron roof and hissed into the red peat, and the wind worried at the four stone corners. A chimneyless lamp was just made to work by means of a bottle with top and bottom knocked off. A haven when the light began to fail!

There must have been a full mile of bird-loud cliffs round the north coast of the island. The line of cliff edge was crinkled by a few small bays which gave a way down to sea level in one or two places. There was the original Puffin Bay, then nearer the hut came Fulmar Bay, a nasty place, and nearest, the low cliffs of Shag Bay. When the wind bore offshore there was silence a few paces back from the cliff edge; then as one came forward the noise broke out suddenly like a blow – roar of waves, chatter and scream of sea-fowl. Loose boulders rolled over the edge exploded satisfactorily on the rocks below and left acrid sulphurous eddies; the sea-fowl swarmed into the air.

In Shag Bay the shags sat close on their fishy nests and twisted their scraggy necks to look up at us. Their guttural dog barks came from dim crevices. Their beautiful eyes were jade green, in sunlight their fishy feathers were glossed and iridescent. The piled boulders at the bottom of Shag Bay were negotiable until we came to a gap of sea too wide to jump, where a seaweed forest heaved in the ground swell. One of those long wooden sheep-troughs would neatly bridge the gap. Back to the shepherds’ hut and back again across the empty island, one of us at either end of an unwieldy trough. We manoeuvred it down the cliff, manhandled it over the boulders. Too short. Ainslie wished to use it as a boat, but a demonstration run at the end of a piece of string was unsuccessful. Back over the boulders, up the cliff and again past the watching sheep to the hut.

Fulmar Bay, the nasty place, was a treacherous cliff of wet earth and lush greenstuff topped with a bastion of sheer rock. In one place an earthy cleft dribbling with water led down to discover three nestling fulmars squatting on a narrow shelf. The only site for an observation hide was between two of them. John set to, shoved tent poles horizontally into the soft soil of the cliff and draped them with rotting sacks from the sheep-pen. Everything had to be lowered on a rope or carried dog-like. The three young fulmars objected and sprayed us with their hot oil, their spluttered-out jets ranged up to two or three feet; once a crab’s leg came up. The nestlings sat surrounded by a circle of scurf from their own down, and looked like nothing so much as oversized grey powder-puffs – which was a cliché description for a nestling fulmar, but no other came so aptly.

Puffin Bay was the hub. On the evening of the 2nd of August the slopes and boulders were crowded with puffins; on the morning of the 3rd not one was left. The sudden autumn exodus to the sea had happened. In a day or two a few birds reappeared, purposeful and busy, feeding late young ones. One evening after that the cliff-side air was again full of flying puffins going fast and in an urgent-seeming manner. They sat again on their slopes, but in silence; they seemed unable to make a clean break with the land.

All the colonists’ ledges were quickly thinning. Guillemots’ activities in particular were easier to follow now that their ledges were less overcrowded. I saw the act of one late egg knocked overboard; its owner waddled to the edge and pecked after it.

The idea that its shape allows it to twist round in the wind is exploded, as is the egg when a careless sitter sends it hurtling to the rocks beneath (T.A. Coward).

The full English name used to be, the foolish guillemot.

The Stack of Handa near Puffin Bay was a feature, probably the tourist feature. The crown of this great lump of separate rock was only a giant’s jump out from the cliff edge. A leaning weathered stake stuck up from the grass on the top, the most startling of any human relic on the island.

A crossing to the Stack had been made in the eighteen-seventies and had been written about by John Harvie-Brown, famous naturalist of the time, who had twice visited Rona (his findings reported in Ronay and known nearly by heart). Two men and a boy from Uist in the Outer Hebrides had got across at the behest of the Scourie landlord, to destroy the nests of the great black-backed gulls which until then had bred there in safety and had increased to a nuisance.

The invasion of the top of the Great Stack was accomplished by means of a rope, thrown over it from the nearest cliff-top of the main island, along which the boy scrambled . . .

Somebody must have been over since the seventies to account for the inanimate, staring stake which we saw. It looked an impossible feat, but last across, according to Seton Gordon, were

a fearless crew from Lewis – men who were doubtless skilled in fowling upon the cliffs of Sula-Sgeir and North Rona – and by means of a rope they traversed those giddy yards with the roaring surf five hundred feet beneath them.

From an empty piece of sea there appeared a large dog-like head, a Great Dane’s head without ears: so startling was the first sight of an Atlantic grey seal. The head looked around, the nose slowly tilted upwards and slid back under water. Shag and Fulmar Bays had each a resident seal. They travelled at the surface, broad backs awash, so smooth, slippery and naked, they were different from any imaginable animal. The sea had taken a dog and had made of it, this. They submerged in a neat duck-dive, splashless and silent; alarmed, and they were down in a flash, a resounding swirl of white water left behind.

The sea was always such a cold and unlikely waste, barren and heaving grey water; I could never really credit that it should contain a teeming life and produce large warm-blooded animals. But from Handa the wonderful west coast fauna revealed itself creature by creature. Porpoises made their revolutions in the Sound, where cruised just below the surface the great bodies of basking sharks. Two black triangles cut the surface and moved along with a little bow wave. Basking sharks would bulk up to a length of thirty feet, said the fishermen of Tarbet.

Black guillemots next showed themselves, called by the local men sea pigeons or tysties. They bred on islets in the Sound of Handa. On one crossing we were landed on an islet containing a foul-smelling crevice with a pile of dung outside. We withdrew the two nearly fledged black guillemots – weighty chickens in pepper and salt – then let them splash back through their ordure into the safe darkness. Adult tysties looked soft and plump and their dusky plumage, entire except for a white mirror on either wing, was set off by beautiful bright red feet. And when they opened their beaks the inside was vermilion. The white wing mirrors of birds whirring low over the sea looked like little patches of broken water. I saw one bird leave a rock and bounce on to the sea, like a painted boat shot from some lido water-chute. The tysties were as novel as all the rest.

One stretch of cliff belonged to a family of peregrines. A buzzard quartered the ground like an enormous moth. From the bracken beds of the interior flew a thrush, a blackbird; there were wrens and starlings; a young robin pecked in at the door of the hut. More remarkable were the ordinary house sparrows which inhabited the caves of the hut, making their careless nests there. Sparrow chatter woke us in the early morning.

The iron roof groaned and the rain rattled upon it – cold, wind and wet. The mainland was easily lost in sea mist that swirled over the island; a half-hearted sun appeared infrequently. All day long the sky emitted a uniform grey light and our days were timeless. We dragged up driftwood from the landward beach and searched for the last of the mushrooms. If it hadn’t been for the birds there would have been nothing to do. One would soon have tired of walking round the island looking at the sheep. Ordinary seaside activities, such as bathing, appeared grotesque.

The mushrooms grew mostly at the back of the dunes where a close pasture reached inland to the ruins of the village. This had evidently been the cultivated land; the remains of drainage ditches still showed. Lying on the grass was a bamboo flagstaff which the shepherds used in their season for signalling to Scourie, two or three miles to the southward. (There continued to be no sign of them.) Only the walls of the crofts remained, standing up from a floor of turf and nettles. There had been nine.

The last generations of crofters had lived on potatoes and fish until in 1845, the year of potato famine, they had to choose between starvation and emigration. They chose America and the island was actually cleared in the spring of 1848. It so happened that none other than Charles St John – of Wild Sports in the Highlands – very nearly saw them go. In the same summer, when he was engaged on his Sportsman and Naturalist’s Tour, harrying the remaining ospreys up and down Sutherland, he made a day’s visit to Handa. As his boat approached the shore he saw, sitting out on the point nearest the mainland, a large white cat.

I could not help being struck with the attitude of the poor creature as she sat there looking at the sea, and having as disconsolate an air as any deserted damsel. ‘She is wanting the ferry,’ was the quaint and not incorrect suggestion of one of our boatmen . . . I passed several huts, the former inhabitants of which had all left the place a few weeks before; and, notwithstanding the shortness of the time, the turf walls were already tenanted and completely honeycombed by countless starlings . . .

What had been the truth of this particular clearance? There was the potato famine; but also Handa was a good sheep-walk. Nowadays the local men said that the Duke of Sutherland had been most to blame; it was a month’s notice, the emigration ship called, then Canada for the rest of the crofters’ natural lives. Charles St John’s evidence, though perhaps suspect, did not agree:

Depending on the Duke of Sutherland’s well-known kindness and liberality, the lower class of inhabitants take but little trouble towards earning their own livelihood. At whatever hour of the day you go into a cottage, you find the whole family idling at home over the peat-fire. The husband appears never to employ himself in any way beyond smoking, taking snuff, or chewing tobacco; the women doing the same, or at the utmost watching the boiling of a pot of potatoes; while the children are nine times out of ten crawling listlessly about or playing with the ashes of the fire.

The Duke, having tried every plan that philanthropy and reason could suggest, has now succeeded in opening their eyes to the advantage of emigrating, and at a great expense sends numbers yearly to Canada . . .

Charles St John lay on the cliff brink of Handa and thought of a snowstorm as he looked down to the teeming birds. When he left the island the white cat still sat looking towards the mainland. When Seton Gordon visited Handa he was with a piper who marched up and down the turf by the village ruins, and played a lament.

The fishermen of Tarbet came and fetched us, we took two or three days at the Sailors’ Home and then, washed and reprovisioned, came back for another spell. Three snipe got up in front of the hut door. Rain fairly hammered on the roof; the inside was beaded with wet which was soon glistening in the light of a driftwood fire. The chimney smoked abominably. The burn became quite a little torrent. After forty-eight hours the wind blew itself out and the rain stopped, the mainland reappeared and the sun came out.

Of the thousands of birds still left we had chosen for a closer look the three young fulmars of Fulmar Bay and a downy razorbill chick, alone on a small ledge near the bottom of Puffin Bay and immediately beneath a big kittiwake colony. The rock below this colony was a morgue of young kittiwakes. Their parents bred on such narrow ledges and the nests were soon trodden down, so that falling off was too easy. One did so as we worked at hide-making below, and fell almost at our feet – plop – quite dead. Several of the nests above had dead young on them, adults only stood on others. The rock walls echoed with onomatopoeic screams, kittiwark, kittiwark, kittiwark.

The razorbills, for whom John thought boar and sow more suitable descriptives than male and female, were pleasing company. The razorbill stood there close in front of the hide, comfortably propped on feet and tail, twisting her razor-beak into every conceivable position. Or she paraded – hop, waddle and jump, up and down the ledge, with wing assistance for the difficult steps. Her disregarded chick followed her about and kept digging its head beneath her, trying to be brooded. Her white bib was so very clean, running up in a point to her neck; her twinkling eye was nearly lost in the deep chocolate brown of her delicately modelled cheek. Her noise was of continuous hoarse grunts, sometimes repeated so fast that they ran into an astonishing trill. The bill of one parent, presumably the boar or male, was notably bigger and deeper than the other’s. It was odd to see that the chick stood and ran on the webs of its feet while its parents followed the common auk fashion of shuffling along on the full length of the tarsi. It was like a nursery tale of evolution, demonstrating that razorbill ancestry had gone on its toes. Soon the chick would be paddling along with the rest of the tribe.

And what had environment done to the razorbill? – peculiar, peculiar creature: boat-shaped body, stumpy wings whirring hard to get it up to the nesting ledge, cold webbed feet to drive it competently through the water and to mount it incompetently on dry land. But why should it so wreathe and writhe its neck, point up its axe of a bill and grunt until it was trilling; why so jerking and awkward with its young? Why indeed be what it was, instead of something else?

At Fulmar Bay I spent an initial half-day cramped miserably into the little hide while the young fulmar in front did almost nothing. Notable activity when it pecked at a fly. Occasionally it preened a little, nibbling into its down. Once it presented its rear end to the edge and powerfully voided a white stream. Now and then it yawned or looked at the sky and settled more deeply into doing nothing.

Old birds circled the bay, flap and glide, round and round, each time nearly but not quite alighting by one or other of the powder-puff young. Their wing-beats looked inartistically mechanical because of the stiff style of wings worked from the shoulder without any flexing at the wrist. The young ones sat unattended, spread out as if they had been dropped from a height, looking as boneless as cowpats. When adult birds did alight they sat motionless and took no notice of the young. When they did move it was with an unbirdlike deliberation, no sharp birdlike turn of the head or quick glance, no bird nervousness. Their big black eyes looked quiet and gentle; some naturalists had used the word ‘demure’ for fulmars. It was misleading; fulmars bite viciously; ‘inscrutable’ was the word. With most birds one could tell roughly what they were at; one watched them and they did something recognisable. This was not the case with fulmars, we found their actions were baffling.

Below, past my feet, were rocks and breaking sea. Farther out I could see the seal which frequented the bay. In another view gulls and a hooded crow were feeding on offal, two rock pigeons preening. A misty rain began. A herring gull standing near its young one with a far-away look suddenly regurgitated a lump of fish. The sacking of the hide touched me all round and I was weary of examining its weave.

For a short time my young fulmar did exercises. It flopped over on one side and slowly stretched out a wing and a leg until they were quivering stiff, a deep luxurious stretch that I watched with envy. Then it stood up on the flat of its weak legs, held out its wings stiffly and worked and jerked them from the shoulder joint – practising for the grown-up, board-winged style of flying. A peculiar farmyard cackling began; it was adult fulmars alighted on another ledge. Two birds sat opposite each other; one opened wide its bill, craned up its head and deliberately cackled at the other. Nothing came of this.

The Scourie motor boat chugged past the bay with a load of sightseers. The seal submerged, the hoodie flew away.