Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

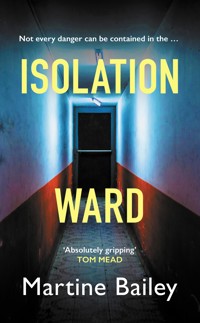

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Serie: Lorraine Quick

- Sprache: Englisch

Yorkshire, 1983. Margaret Thatcher is in Number 10, 'Thriller' is on the radio and Lorraine Quick is having to put plans to tour with her band on hold due to work. With her expertise in psychometric testing, she is being sent to the Yorkshire moors to build a PR-friendly team out of the ragtag staff of the infamous Windwell Asylum as it transitions into a modern, top-security unit housing some of the most dangerous criminals in the country. And then Lorraine stumbles on a brutal murder that has taken place despite the fifteen-foot-high perimeter wall and the heavy-duty locks. Between the asylum's lingering reputation for violence, the haunting underground tunnels of the old institution and the arrival of almost-old flame DS Diaz to investigate the murder, events are coming to a head for Lorraine.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 451

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

3

ISOLATION WARD

MARTINE BAILEY4

5

To my dear sister, Lorraine, after whom I named my heroine.

6

Contents

CHAPTER ONE

Monday 26th September, 1983

The TV screen was filled with a vast towered and turreted building that might have been a Baroque palace. Yet at second glance, it was stained as black as soot by Yorkshire rain and creeping mould. The camera pulled back to reveal an asylum complex the size of a village: some of its roofs green with creeping moss, and a scattering of its high Gothic windows boarded up with plywood. Above it all soared an Italianate tower bearing a large pale-faced clock crowned with battlements of black-toothed stone.

The documentary’s female presenter came into shot, huddled in a crimson coat and scarf, dwarfed by a monstrous arch topped with rampant stone beasts.

‘The inquiry into the scandalous events at Windwell Asylum has delivered its findings. The only possible response is to close down this relic of the cruel Victorian past, and indeed the asylum’s grim corridors and tunnels are scheduled to be destroyed. A modern top-security unit is in the process of being built close by, and the Secretary of 8State with responsibility for health has assured Parliament that the team in charge will keep the most dangerous criminals in the country safe – and also keep us safe from them.’

‘Come on, love. Are you asleep?’

Lorraine Quick raised heavy eyelids to find her mum standing over her in her dressing gown, the television’s light flickering across her fine-boned face.

‘Yes. Sorry.’ Glancing towards the TV, she caught the final shot of a dilapidated mental asylum as World in Action’sjazzy organ theme music played out.

Blearily, she noticed the scattering of personality tests and overhead projector slides that surrounded her, and shoved them into her satchel. So much for preparing tomorrow’s session. Her newly created job as a specialist in Organisational Change was too busy and exciting to cram into a 9-to-5 day. Tomorrow morning she’d just have to busk her presentation. She switched off the TV and spread a sleeping bag and pillow along the settee. She couldn’t blame her mum for keeping her own bedroom, which she now shared with Lorraine’s eight-year-old daughter, Jasmine. Any day now, the housing association would surely write to her about a house in Salford’s redevelopment scheme.

Also waiting on the table were the school test booklets she had been coaching Jasmine to complete over the last few weeks. Jasmine was bright, but she wasn’t familiar with the types of questions used to win a junior scholarship to a grammar school. And if personality testing had taught Lorraine one thing, it was that familiarity with the questions’ format was a serious advantage in a test. Yawning, Lorraine 9marked all the practice questions Jasmine had completed on arriving home from school. Tired out but satisfied with her daughter’s improving performance, Lorraine settled down for a contented night’s sleep.

Tuesday 27th September

The Lancashire Hospital Board met at 9 a.m. and Lorraine was waiting for them, her first slide ready in place on her portable overhead projector. It was a cold autumnal morning and her old Metro had been almost alone on the multi-lane M61 motorway. A grey dawn had been scarcely breaking, a mere glimmer through the rain, when she first arrived. She yawned and wished she could transform herself into a morning person. After all, she only needed to get through this final week’s work before taking a whole two weeks’ annual leave on the German tour with her band, Electra Complex.

An approaching flurry of footsteps rang out in the corridor. She took a steadying breath and stood to greet her audience of hospital managers and begin her presentation. She gave a series of reasons why the hospital should take part in her project to use personality testing to help select staff. Mostly, they were self-evident: finding better-suited and more motivated employees, avoiding rogue applicants, reducing high turnover. This morning, only the hospital’s general manager was resisting common sense, trying to find a reason not to take part. Former wing commander Frank Chichester was exactly the type of man Margaret Thatcher wanted in a top NHS job: an outsider from the RAF, gruff, tough, and to Lorraine’s mind, pretty dense. He kept asking 10her how his busy staff could find the time to waste on all this ‘rigmarole’. She stifled her honest thought, that if his staff were too busy to care about the calibre of who they employed, that had to be his fault.

She put up her final slide, which posed the question of cost to the hospital. The answer was that there was no cost, as Lorraine had managed to find a grant to fund the whole project. Even the no-nonsense medical director managed a smile in her direction, followed by a sly sideways glance at the wing commander.

‘I’m for it,’ said the chief nurse. ‘We need to recruit the best nurses at our first attempt.’

The personnel director spoke up next. ‘I’m in favour, too. Unsuitable staff cost us a fortune in re-advertising and retraining.’

They all waited for their boss’s response.

Suddenly outnumbered, he caved in and flapped an impatient back of his hand towards her. ‘Very well. Liaise with Personnel.’

After the room emptied, she packed her satchel, feeling buoyant. The title of her ‘Square Peg Project’ always gave her a secret frisson of pleasure. Its origin dated back to a conversation she’d had some six months earlier, with Detective Sergeant Diaz of the Greater Manchester Police. Under the immense pressure of a murder inquiry they had shared a fascination with psychological techniques, and one favour she had done for him was to test his own personality. Their profiles had proved to be uncannily similar: both intuitive introverts who loved working alone, both secretly ambitious and determined. But whereas she was open and rebellious, Diaz’s ambitions were fuelled by a disturbed 11childhood and a profound mistrust of sharing his emotions. They had both agreed that they were square pegs in round holes, unsettled in their jobs, though there was more to it than that. From almost their first meeting she had felt an invisible bond between them, that sparked to life whenever they caught each other’s eye or tuned into each other’s thoughts. There had been that one glorious but disastrous night when they had curled body around body, talking in the candlelit darkness, opening up their raw, open selves. And then, almost before it had started, it had all turned sour. He had failed to tell her he was already committed to a fiancée named Shirley who was bearing his child.

Furious, she’d told him that it was over. And yet she had named her first crucial project after that conversation they’d shared. Square Peg had felt like a positive decision. Suddenly she laughed out loud. She hoped the symbolism wasn’t some sort of sexual Freudian slip. Diaz, if he were here, would laugh at that idea of his having a ‘square peg’ trying to fit in a round hole. They hadn’t ever had a chance to find out.

‘Miss Quick?’ The receptionist arrived with a phone message in hand. Dreading a calamity at Jasmine’s school, she unfolded it: ‘New appointment with Mr Morgan, North West Regional Director, at 4 p.m.’

No, no. That clashed with her afternoon presentation at the next hospital on her list. She would have to reschedule. Morgan truly was a selfish git. Still, no way could she ignore a summons from the man who had recently appointed her to this scary but impressive job. And she needn’t worry – she had plenty of good news to give him. 12

The Regional Director of Personnel and Legal Services, to give him his full title, was nothing like the wing commander. Morgan was a former employment lawyer, a deeply introverted man of few words but all of significant weight. She was not offered refreshments. When she began to update him on the success of Square Peg, he lifted his palm to silence her.

‘That’s not why you’re here. You saw that exposé of Windwell Asylum last night?’

She nodded, though she had only glimpsed the last few seconds of footage.

‘You know that our health secretary is the ultimate overseer of this country’s special hospitals? Those institutions have a history of absolute failure in every way. This cannot continue. As you know, the old Windwell Asylum is being demolished and a modern top-security unit has just been built beside it. That’s the easy bit. The bricks and mortar – or should I say razor wire and steel.’ Morgan smiled, showing pointed little teeth. ‘The hard bit is getting human beings to properly direct what goes on inside those places. The new director, Doctor Voss, is having some issues with his team. Those issues need to be resolved. That’s where you come in.’

Lorraine struggled to hide her dismay. One thing she loved about working across the whole northern region was that she could move around freely, without feeling trapped inside an institution. And here was Morgan, trying to send her to one of the most oppressive hospitals in the country.

She could barely follow his words as he described the need for an expert to work with Windwell’s senior staff and miraculously transform them into a functioning team. 13It wasn’t a team-building expert they needed, it was a magician.

‘As you’re already on the payroll, there seemed no point in looking elsewhere. You’ll be seconded for a month to work directly for Doctor Voss. We’re depending on you to turn Windwell into a good news story.’

Seconded for a month? Jasmine’s scholarship exam was booked for a week hence. And the German tour with the band started next week too.

‘When is this, exactly?’

‘We’ve arranged for you to report to Doctor Voss, first thing next Tuesday morning.’

‘I’m sorry, I have two weeks’ leave booked from next Monday.’

‘Cancel it.’

‘I can’t. I have commitments in Germany.’

Morgan leant back in his leather executive chair and narrowed his eyes at her. ‘You’ve been here two months already. All you’ve produced so far is a mediocre plan to improve selection. We’re looking for positive headlines, big breakthroughs. Here’s your chance. A national profile that proves that all this pseudoscience of yours actually works. Convince me to continue funding your job. Your contract is still probationary. I can end it tomorrow if I choose.’

Lorraine could produce no satisfactory response.

‘Do I make myself clear?’

‘Yes.’ She was damned if she’d call him ‘sir’, like his other subordinates.

She turned around, and briskly left the room.

CHAPTER TWO

Wednesday 28th September to Sunday 2nd October

The rest of Lorraine’s week was spent painfully extricating herself from the best parts of her life. Lorraine had only heard about a potential scholarship for Jasmine when accidentally eavesdropping on Morgan’s secretary as she chatted to a friend on the phone.

‘Yes, it’s an exam to get straight into the junior school that feeds into the grammar. All fully funded,’ the secretary had crowed. ‘And only a very few of us are in the know,’ she’d added in an undertone that Lorraine barely caught. Lorraine had investigated the opportunity and discovered an exam for entry at nine years of age. She knew it would be difficult for Jas – but not impossible. And it was a seriously appealing chance for Jas to challenge those privileged ‘very few of us’, and show them what for.

Lorraine had been working through past papers with her daughter and now reluctantly acknowledged that maybe someone else would need to coach Jas for her exam. Her mum had offered, but she was even less familiar with 15modern maths than Lorraine. Finally, she had found a retired teacher, a Mrs Levitt. Jasmine wasn’t keen, and neither was Lorraine’s mum, as the weekly sessions involved two buses into Trafford and back, in the cold and dark evenings after school.

Next, she despondently drove to the band’s rehearsal room in Didsbury’s bedsit-land and explained that she couldn’t join them on the German tour.

‘What’s the problem? Walk out on the tossers,’ protested her oldest friend, Lily.

‘It’s not just a job, it’s everything that comes with it.’ She found she was fighting back shameful tears as she ran through her reasoning. ‘I’m high on the list for a new house and I need a job to pay the rent. And when we get it, Jasmine can go to a really good school. The primary she’s at is chaotic. She’s bright and keen, but that’s all being slowly thumped out of her.’

Lorraine didn’t think the rest was worth explaining. The Square Peg Project was the best use of her interests and enthusiasm she’d ever found. It was always hard for people with her personality type to apply logic to their situation, but this time she forced herself to confront the bare facts. At the end of her month away she’d be back playing with the band. But it felt too high a price; she alone would miss the high point of their musical careers so far.

‘Thank fuck you’re only the bass player,’ said Dale gleefully, which was bloody rude, coming from the band’s newest member. ‘I know someone who could do it. I mean, it’s not like you carry the tunes or anything.’

‘Who is it?’ asked Lily.

Dale had a mate of hers called Gogo, a name that 16Lorraine found patently stupid. Apparently, this prodigy could play any instrument and learn a whole set in no time. ‘She’s rock solid,’ Dale kept saying. ‘And she’s on the dole, so she could do with the money. And she’s got loads of time, too.’

Lily offered to give her a try-out, and that was that. Before Lorraine left them to rehearse in earnest, she pulled Lily onto the attic landing, clutching her sleeve.

‘For our friendship’s sake, don’t make this girl permanent. I’ll be back in a month and then I’ll be a hundred per cent here for you.’

With genuine hurt in her eyes, Lily complained, ‘I totally relied on you. Me and you, it’s our band. And now you’re off.’

‘It is our band. We’re the only ones who’ve been slogging away at it for years. We’ve written nearly all the songs. I promise I won’t let you down again.’ She stared into Lily’s hurt eyes, desperate to connect and convince her. ‘I promise you, I’ll write some new material while I’m away. Then we can take that out on the road.’

Monday 3rd October

The following Monday afternoon, Lorraine reluctantly loaded her car and hugged her mum and Jasmine goodbye. After finding her way onto the M61 she settled into the monotony of motorway driving. Soon blue and white signs proclaimed Preston and the North and the little car was climbing over the rugged tops above Accrington towards the Pennines, which formed the spiky spine of Britain’s 17back of beyond. Entering the bleak wastelands of high country she felt uneasy, sensing her increasing distance from Jasmine.

Still, the practical arrangements had worked out well. On the whole, money for its own sake disgusted her, the merchant bankers in red braces and yuppies with their designer gear and flashy houses. Yet she was learning that money could give you options. It meant that her mum could leave her crummy job at the newsagent’s and look after Jasmine. Guiltily, she had realised she would barely miss the £100 a month she could pay her mum to stay at home and care for her daughter. Jasmine’s happiness and safety, her mother’s chance to enjoy a decent rest – there were plenty of reasons to succeed at this project.

CHAPTER THREE

The setting sun was casting purple shadows over the surrounding moorland when Kevin Crossley shuffled back into his office after yet another exhausting meeting. He was working late again, a martyr to the closure of Windwell Asylum and the transfer of patients to the new state-of-the-art top-security unit. All of the 430 patients classified as too dangerous or violent ever to be returned to the outside world were currently crowded into Phase One of the multi-million-pound building.

The clock on his wall said six-fifteen. Tonight Kevin had planned to be home by six to prepare for one of the most important encounters of his life. For months he had brooded over his decision and at last everything was in place. He was approaching the end of his career and rather fancied himself as Justice, restoring balance to the scales that weigh good and evil. There had been a great wrong done, he could see that now, and tonight he would make a peace offering and set matters right. It was just his bad luck that hare-brained Doctor Voss 19had conspired to make him late, interrogating him for the last infuriating hour. Kevin’s new boss had wanted to know all the ins and outs of his job as hospital administrator. Voss’s questions were typical of a psychiatrist, probings that subtly undermined him for no more reason than that Kevin was a traditionalist. It didn’t matter to Voss that he had worked at Windwell for nearly forty years, and run a tight ship as administrator for the last seventeen, never mislaying a file. Case notes, court orders, permits and punishments: almost every piece of paper save for the doctor’s prescriptions had been date-stamped, dealt with and signed by Mr K. Crossley.

He despaired of the crazy ideas that Voss was threatening to introduce. His latest madcap notion was to let the patients have a say in how things were run. As if a load of psychopaths could be trusted to run a hospital? He’d like to bet a hundred quid that Doctor Voss wouldn’t last long in the job. Windwell had a history of proud traditions that no doctor was going to change. He, Kevin Crossley, would do the job as he’d always done it for the next two years, until he got his gold clock and his generous NHS pension paid out as he’d carefully instructed.

Though he had already cleared his desk, to his irritation, he spotted a new piece of paper awaiting his attention. It was a message on Titan Construction letterhead, handwritten in their usual uneducated scrawl:

URGENT

Date: Monday 3rd October, 1983

To: Mr Crossley

From: Security Gate Phase 2

Come at once to Seclusion Block Cell 17 Phase 2. Otherwise we have to call the police in. 20

What could have gone wrong now? Wearily, he pulled on his overcoat, determined to head off home just as soon as he’d dealt with whatever routine procedure had stumped Titan’s staff this time.

Night had fully fallen by the time he set off across the deserted site – sorry, campus, as Voss liked to call it. Were the lunatics taking over a flaming university? You couldn’t credit it. As he hurried along the concrete pathway towards the new Lego-like building, he glanced over to the distant silhouette of the old asylum. He had arrived there at Windwell Asylum for the Criminally Insane as assistant clerk just after the last war, and even as a newly demobbed twenty-one-year-old he’d had a grander office than this new abode, with its mass-produced plastic furniture, and, of all things, one of those new-fangled personal computers. Paper never lets you down, he’d told Voss. Paper doesn’t need electricity and tapping on keyboards to access information. The truth was, he didn’t have a clue how to operate one of those weird machines. He missed his old hospital administrator’s office in the asylum; the oak-panelled walls and heavy carved Victorian furniture. The one item he’d refused to give up was his wide leather-tooled desk. Giving out orders felt so much easier from behind that symbol of his absolute authority.

Phase Two of the new site was running weeks behind schedule. He walked straight through the gap in the fifteen-foot-high perimeter wall that still awaited delivery of its huge double-locking gates. A bright fluorescent light shone out from the security lodge, but when he rapped on the window no guard was at his post. Call yourself a twenty-four-hour security service, he told himself. Anyone 21could drive up and nick some equipment. In fact, that was probably all that these security nitwits had called him over to complain about. With his master key he let himself through the pedestrian steel gate, hearing it clang loudly behind him. It was only then that he realised that the inner courtyard wasn’t illuminated. Didn’t Titan realise that bright lighting during the hours of darkness was an essential component of the high-security policy? When he found that absent guard, he’d enjoy putting the fear of God into him for his negligence. He glanced over to the newly operational buildings of Phase One, noticing that the overcrowded wards of all-male patients were much closer to this unlit area than he’d expected. If the security guard had been present, he could have used the lodge’s phone to complain to Titan’s duty manager. And even better, he could have borrowed a torch.

He was lingering by the gate, not liking the look of the courtyard’s impenetrable blackness, when he spotted a faint light in the seclusion block. Of course – it must be the security guard from the lodge waiting for him. He set off slowly across the courtyard area, fearful of stumbling into a random pile of builders’ tools or detritus.

Reaching the open door and finding no one waiting, he called out, ‘Hello, it’s Mr Crossley here.’

The light barely reached him from a low-wattage glow in the far interior. He listened and heard no movement. Cursing these delays, he stepped inside a corridor that smelt of fresh paint. He groped along the wall to find the light switch, but when he clicked it, no illumination appeared.

‘Hello there,’ he repeated, less certainly. In the gloom, the seclusion cells had their usual troubling appearance. 22The corridor was lined with a series of small, bare rooms designed to isolate difficult patients, entirely empty save that each contained a waterproof mattress. The doors he passed were closed, bearing heavy-duty locking systems and the narrow Judas slits the staff used to observe their charges. Only the very furthest cell stood open, casting a dim light from its interior. Now that he was here, the faint bell ringing in his memory grew louder. Of course; he’d had the misfortune to deal with an incident in another Cell 17 back in the old asylum. Taking hesitant steps forward, he fancied that behind these closed doors someone might be hiding, might be silently laughing at him even now.

Approaching the final, softly lit cell, he could just make out the sign ‘Cell 17’ beside the door. The door was ajar, but when he thrust it open, he let out a cry of terror. What the hell …

Crimson graffiti had been daubed on the facing wall. ‘RIP Campbell. Your next.’ The interior light was nothing more than a battery-powered storm lamp standing on the floor.

Crossley stood on the threshold, struggling to catch his breath. Junior Campbell was the name of a patient who had been found dead in Cell 17 of the old asylum three years back. A tribunal had been held but the police case had been hopeless, for after all, who was Campbell? He was just a bothersome black lunatic who had always got on the nursing staff’s nerves. It had been a terrible strain to go to London and speak at that government inquiry. Still, the management board of the day had kept the whole mess quiet.

Crossley wondered if he could somehow cover the 23taunting message up before anyone else saw it. Curious, he stepped inside the cell and touched the red paint, feeling sick with apprehension. Now Doctor Voss would find out about his statement to the tribunal and no doubt judge his loyalty to Windwell as a blot on his career.

A draught sprang up and chilled Crossley’s neck. He spun around and for an instant, glimpsed a figure in navy-blue serge and a peaked cap.

‘Hey!’ he cried out. The next moment he was thrown backwards so that he toppled over, landing flat on his back and banging his head against the newly plastered wall. Before he could raise himself to protest, he sensed the person moving above him, and after the briefest of moments, a rush of air as a heavy object swung down, down, onto his brittle skull.

CHAPTER FOUR

Lorraine saw a sprinkle of golden lights that might be Burnley. It was time to pull off the motorway. She moved the car down through the gears and swung onto unfamiliar A-roads. Soon she could sense a vast emptiness beyond the strip of unlit road as the little Metro crossed mile upon mile of moorland. For a long time she saw no lights at all, save for her car headlamps’ reflection on drystone walls and the occasional farm gate. There had been no road sign for more than twenty minutes. The little car was climbing now, and she steered it close to a steep bank, fearing an invisible drop beyond the road’s edge.

At a sharp turn her lights picked out a sign: ‘Windwell Village’. Thank God for that. She was tired and her head was buzzing from the noisy rattle inside the car’s cabin. The silver crescent of the moon faintly illuminated a black shape crouching at the top of the hill that seemed to blot out the stars. Windwell Asylum. She reached its high boundary walls and ‘Danger No Entry’ signs. Yawning, she scanned 25the road for signs to Windwell village where some sort of hospital accommodation awaited her.

From the edge of her vision, a young woman sprang out in front of the car. Lorraine slammed her feet down on the clutch and brake. The car slewed left, in a juddering emergency stop. Lorraine had missed hitting the idiot by inches. She was a teenage girl, hippyish, with waist-length fair hair. Now she stood her ground, staring at Lorraine and whooping like an animal, with a bravado she guessed was chemically induced. More teenagers emerged, moving unsteadily across the road. Lorraine let them cross in front of her. First, a lean and classically handsome Asian boy flickered past, then a spike-headed punk, broad and muscular, banged on her car’s bonnet, pulling a menacing face before chasing after the others. Last in line was another teenage girl, white-faced and fey, in jeans and cowboy boots. Lorraine could hear them, excitedly talking in stupid voices and making ghoulish whooing sounds. She waited for them to leave, in no mood to tangle with a group of local potheads. As her hand groped for the gearstick, a scrap of conversation reached her.

‘—that woman in the car? She doesn’t belong here.’

Lorraine set off, juddering over slippery cobblestones as the sparse lights of Windwell village came into view. Parking up at number 16 on the high street, she was relieved to see she had been allocated a stone terraced cottage, a small retreat all to herself.

When Ella first saw the car’s headlamps she thought it was a UFO rushing towards them. Then Oona had seemed to fly away like a bat released from the underworld. Somehow, 26her friend had arrived on the other side of the road. Wow – Ella blinked and grinned. Tonight Tommo’s mate Krish had shared some amazing hash.

‘Who’s that woman in the car?’ Oona asked. Ella could just make out a fair head of hair and a pale hand on the steering wheel. ‘She doesn’t belong here.’

Tommo was nearby. ‘I dunno. Some offcumden. Probably lost.’

‘No.’ Oona spoke in the mysterious voice she used when telling people’s fortunes. ‘She’s here for a reason. Bringing trouble.’

The woman’s car drew away, red tail lights heading towards the village.

‘What’s up?’ Krish had suddenly appeared at her side. At first Ella had dreaded meeting this Asian lad Tommo hung out with, but now she’d warmed to his considerate nature. Tonight she thought he looked nice; in his crisp white shirt he shone like an angel.

‘Nowt worth fretting about,’ said Tommo, waving them on like a commando leader. ‘Right-o. The best way through the fence’s just a bit further on. Everyone, keep your traps shut. The security bloke will’ve done his rounds but he in’t deaf.’

What an oaf Tommo was, Ella thought. God knows why Oona was going out with him. He had tattoos for one thing, stupid Nazi eagles on his forearms. God, that was so … National Front. Oona was always talking about how she’d first met him in the hospital canteen and seen an animalistic aura glowing around him. Tommo was overpoweringly large beside Oona, his hair gelled into crimson spikes. His clothes were faded black, his favourite an ‘A for Anarchy’ 27T-shirt. And he talked too much, lots of gibberish that he thought was clever but was just bits of old books or lines from boring films.

Next to Tommo, Krish was laid-back and smart. The last time they’d met he’d confided how his uncle insisted he worked in his shop to pay his keep. When she asked what he’d rather be doing, he’d told her about a course in electrical engineering that looked right up his street. He was completely uncool about wanting to go to college. Ella liked that.

Oona was way above Tommo’s league, too. It was a whole amazing week since she’d saved Ella, on the night she’d boarded a huge shiny bus to anywhere so long as it was far away. She’d been staring out of the window into the night, like it was some kind of ultra-boring TV channel.

Then someone had said, ‘Want one?’

Ella had ignored the voice. Despair pressed against her chest. The darkness up there on the hills. The emptiness, just like her insides. Trying not to think about what she’d done.

‘Here you are. Have it later.’

An elegant filter ciggie landed in Ella’s lap. She looked around. The girl had a whole packet of twenty golden Bensons. She let the girl light her ciggie with a flashy gold lighter and drew on it, tasting the quality. On the farm she sometimes smoked roll-ups; she rarely had any cash. Carefully, she eyed the girl up using her just-down-from-the-hills eyes. Oona was maybe seventeen, waist-length fair hair like a princess, pop star make-up, the sort of Barbie face that lads really go for. Clothes-wise, her cobweb 28sweater, flowery maxi-skirt and boots were top gear.

She’d asked where Ella was heading and she’d forgotten, so her story was a right muddle. In the end Oona had asked if she wanted to crash at her mum’s place at Windwell.

‘Isn’t that the loony bin?’

Oona hadn’t minded her saying that. ‘Yeah, but it’s cool. Me and my mum work there so she’s got a house with the job. You can have a room in the attic till you get yourself together.’

‘Why?’ she’d asked, suspiciously. ‘Why do you want me to stay?’

Oona had laughed. She’d told Ella – well, it was Eileen back then, before Oona gave her a new, more trendy name – that she was a white witch. She did her best to be a kind person – well, most of the time. It was about karma and all that, about the universe giving back to you what you gave to others.

‘Go on, come back to mine tonight. Look, we’re almost at my stop.’ Oona stood up and put her bag over her shoulder, her Indian bangles jangling.

Staying at Windwell had been great – or cosmic, as Oona would call it. Oona said she liked having a live-in friend. Ella was someone she could moan to about Tommo and her mum, and show off her new clothes to, and educate about all that spiritual stuff. Funny though, that Ella still hadn’t felt like telling Oona why she’d run away. Maybe she didn’t entirely trust anyone but herself.

Now, as they followed the two guys in the darkness, Oona linked arms with her. ‘You OK?’

Ella was dragged out of her stoned reverie. ‘Can’t we go home?’ 29

‘Soon,’ she soothed. ‘This is such a cool place. You don’t want to miss it.’

Ella didn’t reply. It was easier to let Oona do the talking. They followed the two guys under the gap in the fence and then under a low-hanging shrub. On the other side the old asylum seemed to rear above them like a great carapace of something that had crashed to earth; an alien ship with sinister intent.

Like kids on a treasure hunt they lit the candles Oona had brought along and trailed onwards, each holding a flickering flame. The hash made them stumble around, their shrieks bouncing around the night sky.

Maybe the moon had chosen that moment to slide out from beneath a cloud, but when she next looked up it was as if the house had risen from the ground like a backdrop in a pantomime. It was a big, very beautiful house; the silver moonlight gleamed down on its blind windows and curly roof mouldings.

‘What is this place?’ Krish asked Tommo.

‘The old nurses’ home. Been boarded up for years. Wanna take a look round?’

Too frightened to be left behind, Ella followed them to a small side door Oona and Tommo said they’d discovered on an earlier visit. Back then Tommo had shouldered the entrance to force a gap a foot wide, but they’d had to scarper when a security bloke had spotted them.

‘It’s a bit small but I think we can all get through.’ Oona squeezed herself inside the wooden frame. Krish came next, then Ella launched herself through the black gap and waited. Finally, Tommo had a go and only just scraped through thanks to his beer belly. Now they were all inside. 30

The first room was just some sort of scullery, a repository of Formica kitchen units and cupboards hanging off their hinges. Next door the proper kitchen was vast and as black as pitch behind boarded-up windows. As Ella thrust her candle forward, she saw the old range all crusty with cinders and a chopping block streaked with gashes and stains. She felt sick to think of all the bacteria festering in here since for ever. Her boots crushed something crunchy on the floor.

‘Shit, it’s not bones is it?’ Panic raised Ella’s voice a couple of tones.

In the murk everyone moved closer together.

‘Rat poison,’ said Tommo, deadpan. ‘They use it in all the empty parts of hospitals. Hey, this is boring,’ he announced. ‘Let’s see the rest of it.’

The hallway was like every nightmare you’d ever had of a haunted house. A rickety oak-spindled staircase curling upwards into nothingness. A mouldering ceiling hung with a cobwebbed light fitting. The flooring of black and white tiles cracked beneath their feet as they shuffled across the room. Tommo reached another door and slowly opened it, making the hinges screech.

‘It’s fucking huge,’ said Tommo, dashing in and twirling around to take in the baronial fireplace and three branching light fittings that hung low with dust-sprinkled cobwebs.

Krish was the first to say it. ‘Man, what a great party space.’

They decided to stay there for a while to plan their party. Krish got his hash out again and Tommo passed round some bottles of beer. Oona and Ella stuck more candles around the room so it looked amazing in the scintillating amber light. 31

Krish held up a miniature cassette player. ‘Seen this? It’s the latest gadget from my uncle. A copy of that Sony Walkman thing from Japan that costs two hundred quid. Only this is made in Hong Kong so half the price.’

They all gathered round the tiny red plastic box scarcely larger than the music cassette tape it contained. Krish handed the flimsy, orange, foam-covered headphones to Oona. When it connected she started to nod to the beat with a wide-eyed stare.

‘That’s mind-blowing. What are the sounds?’ she said, shouting too loudly.

Krish was smiling at Oona; all the lads stared at Oona. ‘Michael Jackson’s Thriller. What d’you think?’

‘Pretty cool.’ She watched him with that Princess Diana upwards gaze through her eyelashes. Then she gave him her mysterious smile.

‘You’re kidding,’ Tommo mocked. ‘That little black kid from The Jackson 5?’

‘You haven’t even heard it,’ she said, frowning.

Ella was plugged in next. She had never heard a stereophonic effect like it; the drumbeat was incredible, the ghostly effects, the bass so deep it rattled her eardrums. It was like a ghost train riding around her skull. Then she grasped what the song was about and yanked off the headphones. ‘There’s a wolf howling in there. And zombies!’

Krish and Oona laughed. Ella gave the headphones to Tommo who rolled his eyes, listening as he sucked on the hot roach of a joint like some old-style tycoon.

‘Shit, man, it’s disco. Monkey music.’ He pulled off the headphones in disgust. ‘You can’t beat Wharfedale 32speakers and a good deck. In the old days tribes danced in a circle, not on their fucking own with some tic-tic-tic driving everyone mad. If we’re going to have a party we need to share the beats. I mean who wants to dance on their own?’

Krish stood up to Tommo. ‘You’re wrong, brother. Soon everyone’ll want one. You carry your own sounds round in your head, man.’

Tommo asked, ‘What else can you get hold of?’

Krish gave him a beautiful white-toothed smile. ‘Colour TVs, ghetto-blasters, video recorders.’

‘I’ll have another of those radio cassette things,’ said Oona. ‘My mum loves hers and I want one, too. I can wake up every morning to my music if I load a cassette and set the alarm. It’s so—’

Tommo interrupted her. ‘Man, I always wanted one of them video cameras. I could record some of the shit that goes down in our unit and sell it to the newspapers.’

Suddenly, he leapt up like a jack-in-the-box. ‘Listen. I’ve just had the best idea ever in the world. Let’s make a video here before this place gets knocked down. Show how fucking amazing it is.’

‘That’s not a bad idea,’ said Oona.

Ella could imagine it in her stoned brain. The dizzy clock tower, this massive party room, the empty corridors. It sounded like a horror show.

Oona was really getting into it. ‘Krish, do you think a video recorder could pick up, you know, spirits?’

Tommo’s eyes were round with excitement. ‘Yeah, yeah. You could call up the spirits, Oona. You know, Sally’s ghost.’ 33

The last blast of hash had left Ella so stoned that she watched Oona speaking what sounded like incredibly profound words. ‘Yeah, we could, you know, literally catch Sally on video. Maybe then they couldn’t knock this place down? If they demolished her tunnel with her in it, it would be like, you know – murder?’

Ella tugged on her sleeve. ‘Who’s Sally?’

Tommo tried to explain. ‘Sally was one of Oona’s family.Oona’s a proper psychic. Tell ’em all about it, love.’

All in a tumble Oona told them about her great-grandmother’s sister, Sally, who was Oona’s great-great-something or other. She’d seen Sally’s records in the admin block, and had even nicked a photo of Sally from the files.

‘You know what they gave as the reason for her being locked up here? She had a baby out of wedlock. Talk about the patriarchy. She was locked up here for seven years and then one day she disappeared. The story is, she escaped down into the tunnels to hide from the warders. She must have thought she’d broken free, free of those straitjackets and restraints. Anyway, a sympathetic attendant took pity on her and smuggled food and blankets down to her. But when the Spanish flu broke out, the attendant was put in isolation and no one else knew that Sally was down there—’

Tommo broke in, eager to get to the ghastly ending. ‘It were only when a nauseating smell began to spread through the asylum that the superintendent even bothered searching for her. Someone had locked the underground boiler room with her in it, starving to death. So she tried to escape by crawling through a narrow pipe. She were found jammed inside a thirty-inch pipe, boiled by a release of hot water.’

‘And now,’ Oona crooned with sparkling eyes, ‘she’s 34Windwell’s most famous ghost. And because she’s my ancestor, I think that gives me a say in this place.’

‘Too fucking right,’ agreed Tommo. ‘Loads of people have seen her. A woman in a brown patient’s dress with a face like a skull. She lives in the boiler room in the tunnels that run just below where we are now. It’s like a catacomb where zombies rise at night …’

He popped his eyes wide, and comically lifted his fingers like talons.

Ella squealed, hating him. ‘I’m not going down there.’ She turned to Oona. ‘He won’t make me, will he?’

‘Not if you don’t want to,’ she soothed.

Tommo wouldn’t shut up. ‘Oona, listen for once, will you. You gotta get the key to the tunnels off your mum, OK?’

‘I don’t know,’ she started to say, resentfully. ‘Can’t you get it? Your dad’s on call, too.’

‘Yeah, but my dad actually uses his keys all the time. He hasn’t just got a doss of an office job.’ In the heavy silence Tommo hectored her again. ‘Just do it, hey?’

She ignored him and Krish cut in. ‘Hold on, man. Have you got a couple of thousand quid to buy this camcorder?’

‘Course I haven’t. Can’t we just borrow one off of you?’

‘Maybe you can rent one.’

‘Brill.’

‘Only that’s the Hong Kong version. The battery don’t last that long. Have you got electric down there?’

Oona pointed up to the dust-laden light fitting. ‘No, all the power’s been switched off.’

‘Aw, there must be some way,’ said Tommo resentfully. ‘Can’t you bring a generator?’ 35

‘My uncle’s got an electrics shop, not a power station.’

Tommo wouldn’t let it go. ‘Well, the security guys have got lights on in their security hut. Can’t we just divert a bit of power?’

‘What if we get caught?’ Oona protested.

Tommo snapped back at her. ‘Oona, everyone except you fiddles their meters. There are loads of ways – coins, bits of paper, divert the wiring.’

‘I can have a go,’ Krish said. ‘When I come back I’ll bring me tools down and have a good look round. But the video rental will cost. It’s a hundred a night but maybe you could manage fifty?’

Ella was watching him, tracing how Krish’s facial bones were as fine as a model’s. Beside him Tommo was a Neanderthal.

And that was it, how the idea started. It was agreed that Krish would come back and try to sort out the electrics to make a video of Sally’s ghost.

As the two lads walked on back to the road together, Tommo was getting loud and manic.

‘When we’ve got Old Sal on video we’ll send it to that Look North programme on the telly. Or, hey, the Fortean Times …’

Somehow Krish escaped Tommo’s orbit and dropped back to the girls before they reached the fence. He angled himself between them.

‘I’ll need to check out the wiring.’ He was speaking very softly but Ella could hear his words, and even his subtle insinuation. ‘If you could get me the key?’

This time Oona wasn’t full of awkward excuses. ‘Maybe. OK, yeah.’ 36

Ella cast an anxious glance to where Tommo was waiting, uncertain how he’d react to his girlfriend secretly arranging to meet his friend.

‘I’ll ring you when I know which day I can get away from work early. Leave the key behind the concrete block by the gap in the fence.’

‘Even better, I’ll see you there,’ murmured Oona.

‘Get a fucking move on, you lot,’ Tommo shouted.

Ella looked away into the darkness, dissecting what she had just heard.

Krish moved ahead of them then, and followed Tommo under the fence. When they’d disappeared Oona clutched her hand, holding her back.

‘No need to mention that to Tommo.’

‘Mention what?’ said Ella. ‘I wasn’t listening.’

Oona gave her a tooth-gleaming smile. ‘Good girl, Ella.’ Then as she crouched to go under the fence, Oona ruffled Ella’s hair, just like she was a fluffy pet lamb.

CHAPTER FIVE

Tuesday 4th October

The next morning, Lorraine set off on foot for her appointment with Doctor Voss at his address in Windwell village. She could have kicked herself for failing to get a prior insight into the director on World in Action. All she had gleaned were a few scraps from the press describing Doctor Voss as bringing ‘new blood’, ‘a fresh pair of eyes’ and ‘bright new ideas’ to the hospital. Well, he sounded far better prepared than she was.

She was searching for the director’s residence amongst the huddle of stone houses on the main street when she was greeted by a striking guy in a duffel coat.

‘Lorraine? So good to meet you.’ The man who grasped her hand with a firm shake looked disarmingly younger than his thirty-two years. Voss was an athletic Dutchman with straight blonde hair falling to his shoulders that gave him an uncanny resemblance to the American rock singer Tom Petty. She took in bright clever eyes, a rainbow striped scarf and an open smile. When he politely enquired about 38her accommodation, she thanked him for use of the two-up two-down terrace, with a kitchenette and a back view of scrubby moorland. The previous evening she’d found a dish of what looked like chicken stew and rice in her fridge, along with some sort of fritters. When she’d reheated the food it had tasted like fire on her tongue, so rich with spices it was unlike any food she’d ever eaten. Hunger had kept her eating, and by the time she was halfway through, she decided she loved the first curry she’d ever eaten that hadn’t come dehydrated from a Vesta packet.

‘Ah, one of Parveen’s food parcels. She’s the hospital’s deputy administrator and a very nurturing woman.’

‘I must thank her.’

Doctor Voss gave a reassuring nod and silently gestured for her to continue speaking.

Her mind went blank. Was she being invited to lay bare her private emotions? She didn’t know how to tell him that she should never have been given this role. She had no experience in building a team and had never even worked in a mental hospital. In fact, if there was one speciality she’d promised herself never to move to, it was psychiatric care. Other parts of the health service gave the public a reasonable return: babies were born, broken bones mended, diseases were at least eased if not cured. But somewhere like Windwell was the ultimate hard place at the back-end of the service. It housed the rejects from prisons, the untreatable offenders, the human beings who needed to be locked up to keep the rest of the population safe.

‘Is there somewhere we can go to discuss my role?’ she asked abruptly.

‘Yes, of course. The easiest way to explain what I’m 39trying to do here is to show you around the asylum.’

Lorraine had to mask her disappointment; she’d been hoping to meet in a peaceful environment where she could ask her prepared questions and share the few team-building ideas she’d scraped together over the weekend. Unwillingly, she followed the director down a rough path towards the massive clock tower that loomed over copper-tinted trees. He marched confidently onwards, secure in leather hiking boots, while Lorraine tried not to trip over in her three-inch heeled black court shoes.

All she knew of Windwell was that it had been built as a hospital for the criminally insane back in 1863, and even then had been plagued with reports of cruelty and neglect. In the last century it had at times been an epileptic colony and then an institute for what were described as mental defectives. Only in the 1960s had it been taken under government control as a top-security hospital, though a string of official inquiries all agreed that the asylum was unfit for any of its avowed purposes.

At last, after passing through a security gate where Voss vouched for her to the guard, they entered a great hall that might have been modelled on a palatial Victorian theatre or Persian court. There were the remnants of a proscenium arch and grand stage, while in the room’s centre were heaped piles of patterned tiles and lavish plasterwork stripped from the walls.

‘This is the much-photographed ballroom,’ he said. ‘The public image of a happy place while around and beneath the rot set in.’

Lorraine had finally caught her breath. ‘Is that what you feel you have inherited? Rot?’ 40

He lifted his bright gaze to hers. ‘Lorraine, I expected a mess. These coercive institutions nearly always breed a psychological darkness inside them. But what happened here, the casual violence towards sick inmates, the hardening of conscience, the culture of brutality amongst the nursing staff – that is a tough stain to scrub away from human souls.’

‘I understood that many difficult staff had been removed?’

‘Some. But I fear that those who stayed on are already tempted to the same path.’

They walked on for what felt like an endless time, up and down corridors imprinted with suffering. He halted in a white-tiled room that now looked grey with dust and black mould.

‘The morgue,’ he announced. The shadowy chamber was dominated by a flat steel table, presumably used to examine the dead. There were unidentifiable stains on its surface and an array of pipes and drain holes on its underside. Relics of old freezers and lab benches hung from the scarred walls.

The director gestured towards the metal table. ‘In recent years three powerless patients died here of unnatural causes. The most recent inquiry revealed that a young patient named Junior Campbell was murdered but the crime was hushed up by staff.’

Lorraine tensed, not wanting to touch a single object or inhale another breath in this place.

‘Just one last thing I want to show you.’ Doctor Voss strode to a doorway next to the morgue and unlocked it with a key from his belt chain. When he began to climb 41down a set of dark stairs, she had to force herself to follow him.

‘Sorry, it seems Titan Construction have had to disconnect the electricity,’ he said, pulling out a chrome torch which sent cross-hatched beams scurrying across the mottled walls of a low tunnel.

‘The underground passages are extensive,’ he told her when they reached the bottom. She wasn’t sure if there really was less oxygen, but what air remained tasted acrid. She knew that most hospitals sat above a labyrinth of tunnels containing storage areas, miles of heating and water pipes, and even occasional miniature railway systems. But Windwell was nothing like most bright and busy general hospitals. She tried to blank out some of what the director showed her, but the worst parts she guessed would permanently lodge in her mind. He stopped outside a series of narrow rooms, which he told her were Victorian confinement cells designed to block out all sight and sound. Inmates had been imprisoned there for at least a week and up to a month. By the time they were released, many had lost their fragile grasp on normality.

‘The real scandal is that many traditional psychiatrists still insist on seclusion as a safe place for their patients. The fact is, it’s more often used to give an easy life to the staff. Back when this place was built there was a theory that isolation calmed the mind, but the opposite is true: to be stripped of dignity and human contact, to sleep on the floor while strange eyes watch you through a slot in the door, these are often traumatic experiences for patients. Too often it’s the start of a vicious spiral of mistrust and violent retaliation.’ 42

Lorraine stepped inside the nearest cell and to her alarm, Voss clicked off his torch. Disorientated, she groped for the damp wall of the cell and steadied herself. Darkness is never absolute blackness, she realised. The insides of her eyelids patterned with dazzling blue and white undulations. Her hand grasped the wall tighter, brushing against something dry and brittle.