1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Ktoczyta.pl

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

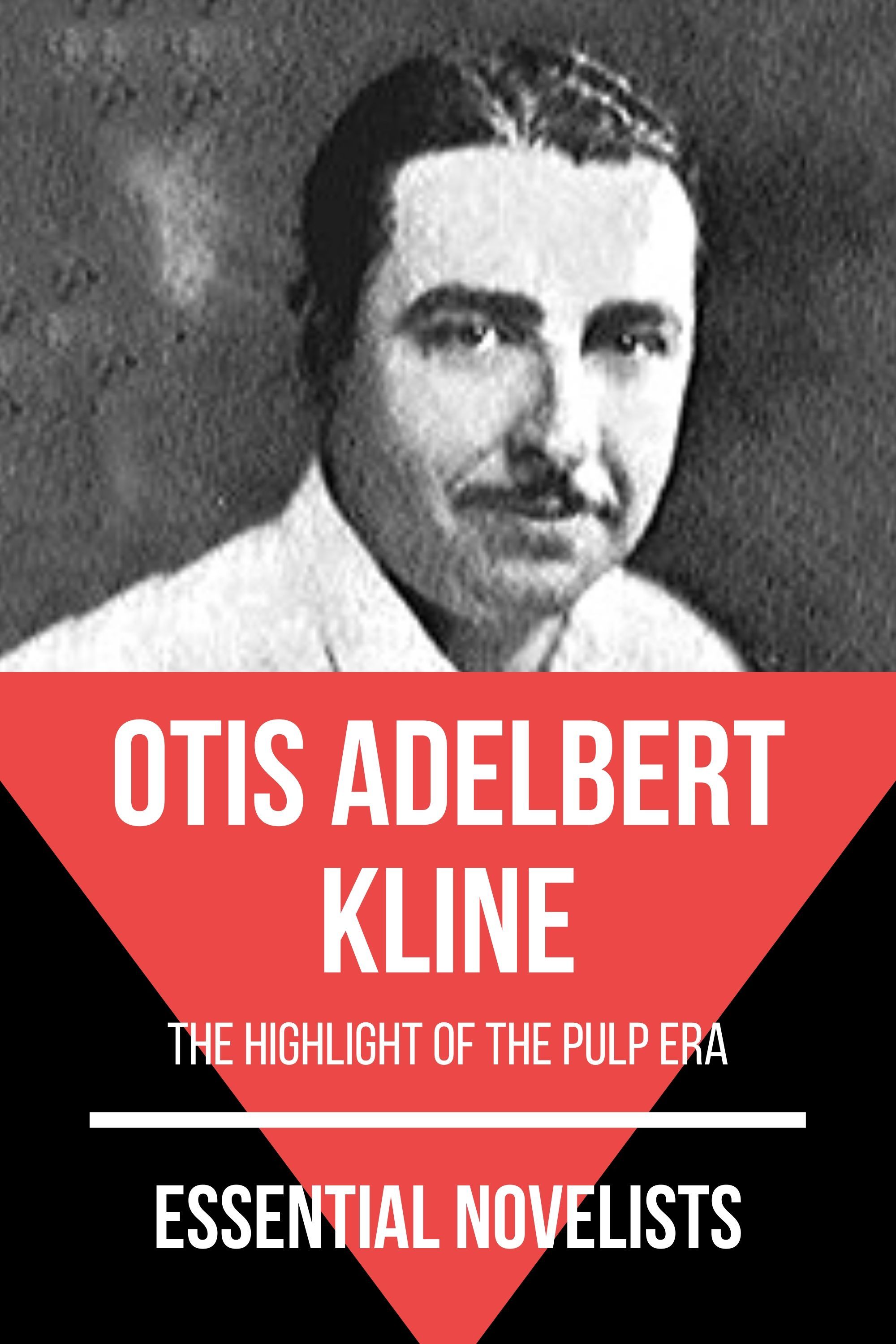

As we continue to follow adventures of „Jan of the Jungle” written by Otis Adelbert Kline, we find him engaged to his fiancée Ramona and reunited with his parents. Together with some friends, they start a cruise on the Indian Ocean. However, the happy days don’t last long for Jan as he gets thrown in the shark infested waters and Ramona gets abducted. Follow the exploits of „Jan of the Jungle” as he strives to save his future wife from a hideous death at the fangs of the Black Tigress in a Temple of Kali! Otis Adelbert Kline was an adventure and science-fiction novelist of the pulp era, best known for his interplanetary adventure novels set on Venus and Mars, which instantly became science-fiction classics. Because of these, and several jungle-adventure novels also, Kline is often compared to Edgar Rice Burroughs.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

Contents

I. A MURDEROUS PLOT

II. MAN OVERBOARD!

III. MAN-EATERS

IV. A FALSE TRAIL

V. JUNGLE TRAGEDY

VI. THE RAID

VII. A STRANGE FUNERAL

VIII. THE BLACK PAGODA

IX. PURSUIT

X. THE MAN HUNT

XI. THE BLACK TIGRESS

XII. MALIKSHAH TO THE RESCUE

XIII. THE BABU'S STORY

XIV. LITTLE EARTHQUAKE

XV. THE HARVEST OF GOLD

XVI. FED TO THE TIGRESS

XVII. A BATTLE OF GIANTS

XVIII. THE BABU'S LOOT

XIX. THE MIGHT OF KALI

I. A MURDEROUS PLOT

THE sun sank, red and sullen, behind the tossing waters of the Bay of Bengal, and the lights of the yacht Georgia A. flashed on as the night descended with tropical suddenness.

Under the gay canopy which shaded the foredeck an after-dinner bridge game was in progress. The four who played were Harry Trevor, American millionaire sportsman and owner of the yacht, a tail, dark-haired man in his early forties; Georgia Trevor, his stately, Titian-haired wife; and their guests, Don Francesco Suarez and Doña Isabella, from Venezuela.

Leaning over the stern rail side by side, but with eyes sullenly aloof from each other, and no thought for the beauty of the Indian night, were Jan Trevor and Ramona Suarez. Like his father, Jan was tall and broad-shouldered, yet he had the auburn hair and blue eyes of his mother. And instead of the stiff, military carriage of the elder Trevor, his was rather the lithe, supple grace of a jungle animal–a grace of movement that had not been cultivated in any drawing-room, but had, rather, been learned from the ocelot, the jaguar and the puma in their native haunts. For, despite his immaculate tropical evening clothes and the fashionable cut of his hair, Jan was but six months removed from the vast trackless jungle of South America that had mothered him.

Ramona was small and slender, a striking brunette with a slightly Oriental tilt to her big brown eyes, which showed that though she bore the name of Suarez, she was descended from a race much older than that which inhabits the Iberian Peninsula. Just now tears quivered on her long dark lashes, for she and Jan had quarreled for the first time. The quarrel had been trivial enough. This tall, red-headed fiancé of hers had been so attentive to her during the six months they had spent on their leisurely round-the-world cruise, that she had become piqued by his inattention of this evening and had spoken sharply to him.

She gazed out over the water for some time in silence. Then, her mood softening, she turned and laid a hand on his arm.

“Tell me, Jan. What is wrong? What has come over you? Ever since we came within sight of this strange jungle you have paid no attention to me. You go about as one in a dream. Or you hang over the rail, staring, sniffing the air. What has happened to you?”

Jan passed his hand over his eyes. “Ramona, I–I don’t know. I have a strange feeling inside me which I cannot understand–a feeling of sadness. I wish I could explain–”

“You need not,” she interrupted, her pride aroused. “You have tired of me, Jan, that is it. I know it–can tell it by your every action. It is well that this happened before we were married–that I found it out in time. I will leave you at the next port. Father, mother, and I can take a steer from Calcutta. Oh, I’m glad! Glad! Do you hear?”

Her last words were uttered in a choking voice, and ended in a muffled sob. Then she turned and sprinted across the deck toward the companionway.

With a single bound, Jan caught her, held her prisoned in his arms. “Ramona, please–” he begged. “You do not understand. I–I–”

She beat upon his breast with her tiny fists, wrenched herself free. “You are a brute, a beast! I hate you!” she sobbed.

Then she darted off and plunged down the companionway.

STANDING bewildered by this sudden change in the girl he had always considered so gentle, Jan waited until he heard the slam of her cabin door. What could he have done to arouse her so? Why should this strange moodiness which had seized him have so startling an effect upon her? And after all, what was it that had suddenly come over him upon their advent in these waters?

He returned to the rail to ponder the perplexing problem, and while he pondered he gazed at the distant jungle over which the gibbous moon was just rising, and from which there came to him strange scents and sounds–strange, yet somehow vaguely familiar.

First, there was the musty odor of decaying wood and leaves, which in every jungle is the same. There was the mingled perfume of many tropical wild flowers which were strange to him. And there were cat scents and cat sounds which he instantly recognized as such, though they were subtly different from those with which he had been familiar in his jungle. There were the calls of night birds, and somewhere a strange beast was trumpeting. Never before had he heard that sound, yet he instinctively knew that only an immense creature could make it.

Jan had never heard of nostalgia, and since he had never had a permanent home, save a cage in a private menagerie, which he hated, it would be difficult to imagine him homesick. Yet the jungle was his home. The jungle had reared him, fed him, mothered him. And while she had taught him many cruel lessons, they had been more than compensated for by the freedom and happiness she had brought him.

And so this alien jungle, which was like his jungle, yet different, had stirred a fierce longing in his heart, a strange, subjective yearning which he was unable to interpret in objective terms. He was drawn as iron is drawn to a lodestone, but he did not realize it. He only knew that he felt a strange sadness, an inexplicable longing; and that for no reason which he could understand, Ramona was angry with him.

As he leaned morosely over the rail, a plump, brown-skinned man who sat in a steamer chair beside the door of the companionway, observed him closely for some time. Then he took a lacquered case from beneath his voluminous garments, selected a cigarette, and lighted it, the flare of the match revealing his turbaned head, his round moon-like face, and the generously padded proportions of his short, rotund person.

Scarcely had the yellow flare died down ere a small, wiry figure slunk out from the shadows and crouched beside the chair of the obese one.

“I am here, babuji,” he said in Urdu.

The fat man did not turn his head, but whispered from the corner of his mouth in the same language.

“The time has come to do what is to be done. See that you do it well. If you fail you will surely die. If you succeed you will not only acquire merit before your black goddess; you will be a rich man as well.”

“I will not fail, babuji.”

“So? Then wait here, my good Kupta, until I again strike a light.”

The babu rose ponderously, and tossed his burning cigarette into the water. Then he circled the deck and mounted the ladder to the wheelhouse, where the second officer, Nelson, stood watch.

“Good evening, sair,” he said with a profound bow.

“Evening,” Nelson replied with a touch of surliness. He was not a man to encourage familiarity from any native, educated or otherwise.

“A cigarette, sahib?” The babu proffered his case.

“No, thanks,” curtly.

The Indian took one, placed it between his flabby lips. Deliberately he fished out a match.

“Look, gentleman!” he exclaimed suddenly, pointing a chubby finger over the bow. “What is that floating in water ahead of us?”

Nelson gripped the wheel and strained his eyes forward. “Don’t see a thing,” he grunted.

The baba struck the match.

“Right there in front of us!” he exclaimed. “Looks like an overturned boat.”

IN the meantime, the small wiry man had been lurking in the shadows, waiting for the signal of the lighted match. He now sprang out and ran swiftly and silently toward the unsuspecting Jan, who still leaned over the rail. In one hand he carried a heavy slung shot. The direction of the breeze was such that the jungle man could not scent the approach of the enemy. And the roar of the propeller drowned any slight noise which might otherwise have come to his acute hearing.

The slung shot whirled aloft, was brought down with sickening force on the wind-tousled red head.

Jan slumped silently over the rail.

His assailant stooped, caught him by the ankles, and heaved. The limp body turned over once, struck the waves with a great splash, the sound of which was muffled by the propeller, and disappeared from view.

A moment later the assassin had melted into the shadows.

Up in the wheelhouse, Nelson was still straining his eyes toward the moon- silvered water ahead. Presently he turned to the babu.

“You must be seeing things,” he growled. “Maybe you’ve got some hashish in those cigarettes.”

“Do not use hashish, gentleman,” said Babu Chandra Kumar in a hurt tone. Covertly he glanced toward the stern rail. It was deserted. Then with an injured, “Good night, sair,” he flung the cigarette into the water, and descended the ladder, whence he waddled slowly back to his steamer chair. As he squeezed his great bulk into that protesting piece of furniture, a voice came from the shadows.

“It is done, babuji.”

“Very good, Kupta. I am sure that Kali will bless you. And here are your hundred rupees.”

The coins clinked softly in the darkness, and the dusky Kupta once more merged with the shadows.

II. MAN OVERBOARD!

BABU CHANDRA KUMAR remained in his steamer chair for a full half hour. Then he took a small teakwood box from an inside pocket. Opening it, he extracted a bit of betel nut which he rolled in a pan leaf with a pellet of lime and a cardamon seed and thrust into his flabby mouth. Closing the box with a snap, he replaced it in his pocket, rose ponderously, and waddled to the starboard rail, where he stood, expectorating red juice over the side and watching the distant shore line which was plainly visible in the rays of the rising moon.

Presently he saw that for which he had been watching–a sampan with its sail bellying in the wind about halfway between the yacht and the shore. Swiftly he glanced up at the man in the wheelhouse.

Seeing that his back was turned, he shouted at the top of his voice, “Gentleman! Gentleman! Assistance! Help! Young sahib has jumped into the water!”

Nelson swung around.

“What’s that?” he bellowed incredulously.

“Young sahib! He leaped into bay! I saw him! He will drown!” shrilled the babu.

“Man overboard!” the officer sang out.

Then he issued some swift orders.

There was instant confusion on the yacht. Cries of alarm from those on the foredeck mingled with the ringing of bells, the roar of the suddenly reversed screw, and the barking of orders.

The portly, red-faced Captain McGrew, who had been smoking and reading in his cabin, wheezed up the ladder, hastily buttoning his jacket. Harry Trevor and. Don Francesco dashed up the opposite ladder.

“Who was it?” Trevor demanded.

“It was your son, sir, according to the babu. Just now he shouted that the young sahib had leaped overboard.”

“Good God! Jan? It seems incredible!”

“Bring her about! Break out lines and life preservers and man the rails! Stand by to lower a lifeboat,” barked Captain McGrew.

Trevor and Don Francesco hurried to the foredeck once more to join the ladies. As they did so, Ramona came running up, her eyes red with weeping.

“What happened?” she asked. “I heard shouts, and the engines stopped.”

“The babu says he just saw Jan jump overboard,” said Trevor.

At this announcement Georgia Trevor went deathly white. Her husband passed a supporting arm around her.

“There, there. Don’t be alarmed,” he said, trying to hide his own concern. “The boy is a strong swimmer. Probably just leaped overboard for a lark. There’s no danger. We’ll have him back on board in a jiffy.”

“But there are sharks in these waters. We saw two big ones following the ship this afternoon. Oh, Harry, we never should have brought him on this cruise. If anything has happened to him, we are to blame, because we insisted that he and Ramona should see the world together, before marrying.”

“No, it is not your fault. It is mine.”

It was Ramona who startled the group by this sudden assertion.

“Why, Ramona! What do you mean, dear?” asked the doña.

“We quarreled,” she said. “I told him I would leave him–never wanted to see him, again. And now he has gone–gone to his death.”

She turned suddenly and flung herself sobbing into the arms of her foster mother.

Standing a few feet away from the group, mumbling his quid of betel, Babu Chandra Kumar smiled knowingly and spat into the water.

THE yacht came about with engines throbbing, then slowly cruised back over her former course, her searchlight sweeping the waves. A lifeboat was unshipped and swung out on its davits, ready to be lowered at a moment’s notice. Men stood along the rails with life preservers, the lines coiled and ready.

The five who stood together on the foredeck moved to the bow, where they anxiously scanned the water, the doña striving to reassure the sobbing girl, and Trevor supporting his half fainting wife.

Unnoticed by the others, the babu crossed the deck to the opposite rail as the ship came about. But instead of futilely gazing at the water ahead, he kept his eyes on the sampan, which was now nosing out toward the yacht.

Aided by the offshore breeze, the little sailing vessel made rapid progress in the direction of the yacht. And because of the reduced speed of the latter vessel, it had no difficulty in overhauling it.

As it drew near, the babu made out a turbaned figure in white standing at the rail. Instantly he ran, shouting, toward the little group in the bow.

“The maharaja comes!” he cried. “It is fishing boat of my master. Perhaps he can help us.”

“The maharaja!” exclaimed Trevor. “How do you know, babuji?”

“That is his fishing vessel. And he is aboard.”

“That’s right. He told us at Singapore that he would be fishing in these waters.”

“Ahoy the yacht,” came a call from the sampan. “Anything wrong?”

Trevor cupped his hands as the sampan drew closer.

“My son is overboard, Maharaja,” he shouted. “We are looking for him.”

“Shocking! I’ll help you search.”

The two vessels cruised about in the vicinity until past midnight. Then both hove to, side by side, and the Maharaja of Varuda came aboard the yacht. He was slight and slender, with an iron-gray beard, a thin, hooked nose, curved like the blade of a scimitar, and small beady eyes that accentuated his hawk-like expression. Save for his jeweled turban, his dress was English, even to a beribboned monocle. Two handsome Hindu boys in their native garb followed him over the rail.

The maharaja bent low over the hand of the heart-broken Georgia Trevor. “Madame, I am devastated,” he said. “But do not give up hope. Your son may have reached the shore. I believe you told me at Singapore that he was a strong swimmer.”

“But the sharks! What could he do against those monsters?”

“They are not so numerous as you might think. As soon as it grows light enough I’ll have my men search the shore line for some sign of him.”

“You are very kind, maharaja sahib, but I fear it will be useless.”

The maharaja greeted each of the others in turn, then addressed Harry Trevor.

“We have done all that is humanly possible tonight,” he said. “I suggest that you drop anchor here, and rest in your cabins until morning. In the meantime, I will go ashore and organize my men for a search of the beach as soon as the sun rises.”

“That’s good of you, Maharaja,” said Trevor, “but I can’t remain here inactive. I’ll go ashore with you.”

“I, too,” replied Don Francesco. “It is maddening to think of waiting here and doing nothing.”

“Come ashore if you like, gentlemen. You will be welcome at my camp.”

“May humble servant come also, your highness?” asked Babu Chandra Kumar. “Should like to help, if your highness will permit.” He paused to snivel and brush away a tear. “I loved young sahib like son and had counted on exalted privilege of escorting him about Calcutta.”

“You will probably be in the way,” said the maharaja, with a disdainful glance at the babu’s obese figure, “but come, anyway, since sahibs will not have any immediate use for your services as a guide. And bring your man. I have heard that he is a good shikari, and we may need men who are expert at trailing.”

“Kupta is very great shikari, your highness. Can follow trail like hound.”

SAVE for the half dozen men who stood guard, the camp of the maharaja was asleep when the party went ashore. Against the dark background of the jungle loomed a score of huge, slate-gray shapes–elephants. A few had lain down, but most of them stood, shifting their huge bulks from side to side, clanking their leg-chains and switching grass up over their backs.

The maharaja waved the babu and his servant to quarters among the mahouts. Trevor and Don Francesco were ushered to the richly carpeted and cushioned tent of his highness. Servants brought assorted liquors, soda, ice, cigarettes and cigars.

“Make yourselves comfortable, gentlemen,” said the maharaja. “My tent is your tent and my servants are your servants. I must ask you to excuse me for a few moments. The elephants are restless, and I wish to inspect them. Only last night my most valuable elephant ran away, and Angad, her mahout, who went after her, has not returned.

“We may have urgent need for the others in the morning, so it would be embarrassing to have any more break away tonight.”

“You mean–” began Trevor.