Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Polygon

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

It's 1975 and Britain is a country in political flux. In Glasgow the dirty old Victorian slums have been razed to the ground, replaced with brand new slums twenty storeys high. Chips are a health food and the very mention of filet mignon would spark a riot on the Govan Road. As its citizens struggle to adapt to their changing world, they wonder what will replace the steel mills and the shipyards, whether they look stupid in flares and what the lyrics of the Bay City Rollers' 'Shang-A-Lang' actually mean? Ten-year-old Steve Duff longs to be poor and neglected like his friend Wally, whose parents are incapable drunks. Frustratingly for Steve, he's saddled with a conventional, stable and middle-class family. Then, over the course of a year, his father has a fling with a barmaid and leaves home, his mother's response is to start a psychology degree, his sister is arrested for demanding money with menaces and his brother gets a girl pregnant.As if the normal indignities of growing up weren't bad enough...This is a funny touching and heart-warming debut novel that will strike a chord with anyone who has been an awkward kid at least once in their life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 461

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

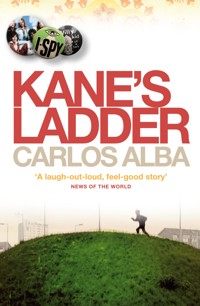

Kane’s Ladder

CARLOS ALBA

This eBook edition published in 2011 by Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

First published in 2010 by Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd.

Copyright © Carlos Alba, 2010

The moral right of Carlos Alba to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

eBook ISBN: 978-0-85790-111-8

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

For Hilary, Molly, Michael and Carmenand my sister Irina

A short guide to old money

In this book I refer to small monetary values by their pre-decimalisation terminology.

Decimalisation – D-Day was the name coined for the momentous change – was introduced on 15 February 1971, but usage of pre-decimal terminology was maintained in everyday speech at least until the late 1970s.

Under the old currency, which had existed in Britain for centuries, the pound was made up of 240 ‘old pence’ (denoted by the symbol d), with twelve old pence in a shilling (denoted by the symbol s) and twenty shillings in a pound. One shilling was commonly referred to as one bob. Some of the old silver coinage continued after D-Day as it had value in the new currency. A shilling, or a bob, became 5p and a florin, or two bob, became 10p. The new coins were ½p, 1p, 2p, 5p, 10p and 50p (where the 50p replaced the ten shilling note). The other coins (20p, £1, £2) have been introduced in later years, and the ½p abolished.

1

It was the morning of my tenth birthday when I experienced the first twinge of what I would later recognise as class envy. I suppose it must have had something to do with reaching my first significant age milestone that made me wonder where I came from and where my life was heading. I lived in a nice house in a safe neighbourhood, cared for by loving parents who regarded my welfare and education as their chief priority. They had steady jobs and we wanted for little. My childhood had not been blighted by alcoholism, drug addiction, poverty or crime and I was not ill-treated by malevolent teachers or abusive clergy. I couldn’t help wondering where it had all gone wrong.

Our estate was one of prim, white-collar respectability. At the top of the hill was Pollokshields, a smart enclave of sanitised politeness and conspicuous silence, where broad, tree-lined driveways, populated with top-of-the-range cars gave way to forbidding sandstone villas.

At the foot of the hill was Maxwell Drive and beyond that the railway line which was the final frontier into the grim, industrial badlands of Govan, where most of my schoolmates lived. I remember that you could see the tops of the shipyard cranes – shadowy figures dominating the skyline like proud and dependable sentries.

Our estate provided a buffer between two communities. That our world of fitted carpets, herbaceous borders and action slacks sat cheek-by-jowl with the mean streets of Govan was a little acknowledged reality. Its inhabitants’ world was one of obscene graffiti, scrawled on the walls of tenement closes; of desolate backyards, punctuated by islands of rotting litter, rubble and the hardened excrement of dogs of questionable lineage; of outside toilets, whose smell hit you in the face with the force of a Peter Lorimer shot; of the acrid odour of frying, artery-hardening chip-shop fat, which hung in the air like a suffocating canopy and invaded your hair and the fibres of your clothing.

Everything about my childhood was comfortable, conformist and pedestrian – an unbending regimen of early nights, sensible shoes and short haircuts. I was dressed in functional, unfashionable clothes – mostly my sister’s hand-me-downs – and I ate healthy, home-cooked meals. I was banned from watching television after eight o’clock and tucked safely between freshly laundered sheets by nine. Reading the women’s underwear section of Mum’s Kay’s catalogue by torchlight was as rebellious as I got.

My Govan contemporaries, in contrast, led a dangerous, skin-of-their-teeth existence of late-night, do-as-you-please chaos. They spoke of strange, exotic experiences for which I could only yearn wistfully – Vesta chicken curries, high-waisters and the naked breast scene from A Bouquet of Barbed Wire.

I longed to be neglected like my friends, to be sent to the Criterion Sea Fish Bar on the Paisley Road to buy my tea and to dog school with the hungover complicity of my elders. I didn’t see the dampness and deprivation in their lives. I looked on jealously at the laissez-faire attitude of their parents, exemplified by a rear-view shot of them sashaying down tenement closes on their way to the pub or the club or the bookies’ or the bingo.

The things they complained about seemed, to me, exciting and edgy. I wanted to be woken in the early hours by police searching our home for stolen cases of Scotch and errant family members. If I was to be corporally punished I’d rather it was at a bus-stop or in a supermarket aisle where bystanders could tut disapprovingly at my parents’ heavy-handedness. I wouldn’t have regarded rowing, drunkenly chaotic parents as a liability the way Wally, my best friend, did. It seemed to me more of a financial opportunity. The drunker his dad got, the more he could steal from him.

Most of all I craved an interesting, impoverished family background. As far as I could tell, my forebears had all been grindingly respectable, God-fearing, middle-class types. Having a greatgrandfather who was a baillie in the burgh of Renfrewshire was hardly adequate playground currency when you were competing against generations of gruel-fed, shoeless wretches from rural Ireland.

What I would have given for just one relative who had died in the potato famine or been terrorised by the Black and Tans. How I yearned to harbour long-held, spoken-only-in-hushed-tones resentment against the Catholic Church, for the way my auntie had been mistreated by an order of sadistic nuns. How I longed to sing, with sombre passion, about how armoured cars and tanks and guns came to take away our sons and actually have the faintest idea what I was going on about.

Because it was my birthday, Mum had promised to take me into town to buy my first suit. The fact that it was my cousin’s wedding the following week, an occasion for which I would require a suit, was one of those happy coincidences in which my mother specialised.

It was a blisteringly hot day and I was sweating as we ran to catch the bus. Mum boarded first and the clippie hoisted me onto the rear plate as the bus pulled away. I asked if we could go upstairs. I liked to sit on the top deck, at the front, imagining that I was steering the ungainly old Routemaster round the twisting avenues, but Mum wouldn’t hear of it because that’s where the common people sat. And its up-stairs, not up-sterrs, she chided, correcting my pronunciation for the hundredth time that day.

I had to content myself with sitting downstairs, alongside the ladies from the big houses. They were perched on the rear seats, dressed in their weekend finery. Most would have already been to the hairdresser on the Paisley Road to have their finely sculpted beehives lacquered into place. They caught the fifty-nine bus into town at the same time every Saturday to spend the day shopping, before meeting up for high tea at any number of the city’s tearooms. A strategically placed bomb in the centre of Glasgow on a Saturday afternoon could have wiped out the country’s entire stockpile of linen doilies.

Mum would pass the time of day with the ladies from the big houses but she didn’t really like them. She said they looked down on people like us from the new estate. We sat opposite Mrs Yuill, whose husband played the organ at the church.

– Not the sort of weather you want the central heating on, she said to Mum, wearing the hint of a smile.

– Indeed not, Mrs Yuill, Mum replied.

– It makes you want to open the door of the deep freeze and let the cool air drift over you.

I pointed out that we didn’t have a central heating system. Mum fixed me with an icy glare. I was about to add that we didn’t have a deep freeze either when I felt Mum’s elbow digging me in the ribs.

– Don’t interrupt, she mouthed. It’s common.

I spent the bus trip planning my choice of suit. Tony, my older brother, had been given money for his sixteenth birthday to buy what he wanted. He came home dressed in a wide-lapelled cream suit with lime green pinstripes and flared trousers. The outfit was rounded off with a black silk shirt, cream patent platform shoes and a white floppy cap like the ones the Rubettes wore.

When he walked in the door, Dad couldn’t stop laughing. Mum was furious – she said he looked like a pimp – but that didn’t mean she was going to stop him wearing them. Tony was her golden boy. He was the cleverest member of the family – definite university material, Mum said – and because of that, he could do no wrong.

I thought his outfit was the most fabulous thing I had ever seen, and I wanted one just like it. Tony had written down the names of all the best boutiques on Argyle Street where, he said, I should get Mum to take me. They all had groovy names like Threadz, Toggs and Glam Gear, but the minute we stepped off the bus she headed straight for Paisley’s department store.

Paisley’s was a traditional, family-owned store on Jamaica Street – the sort of place where you got dressed up just to shop in it. Located on several, mahogany-panelled levels, it was like a stately home with cash registers. The male sales assistants bore all the spit-and-polish, wax-tipped hallmarks of ex-military types, while the women staff – the genteel daughters of bank managers and kirk elders – looked like they were just killing time until their bridge club met.

There was nothing remotely democratic about Paisley’s. It actively discouraged any upstartish notion that customers might have an opinion about what they were buying. You shopped there on the strict understanding that you were going to be patronised from a very great height. For my mother, it was always the first stop on any visit to town. Though she could rarely afford to buy anything, it gave her the opportunity to drop into conversation the fact that she had been there.

We made our way to Boys’ Clothing where a fey officer type with halitosis measured me up before pronouncing on what was ‘best for the lad’. I was dispatched to a curtained cubicle carrying a navy blue, single-breasted, pure wool jacket, which bore a remarkable resemblance to my school blazer, only without the badge, and a pair of grey trousers. When I returned, the assistant fussed around me, hoisting the jacket around my shoulders and pinching the trousers in at the waist.

– They’re a touch on the generous side but the lad will grow into them, he stated in a tone which indicated he would broach no challenge.

To my dismay, Mum failed to demur and before I knew it, we were making our way towards the cash desk with the offending articles. Through gritted teeth, I tried to tell Mum that I hated them, that she was wasting her eight pound fifty and that I wouldn’t be seen dead in them. I thought I was getting through to her but then the foul-breathed assistant intervened, asking me if I liked them. I felt my face flush with embarrassment. I wanted to say they were the most hideous things I had ever clapped eyes on but I was ten years old and he was an adult and respect for my elders was a principle too deeply ingrained to challenge.

– They’re very nice, was all I could say.

For a birthday treat and, I suspect, because she felt guilty about the clothes, Mum took me to the Java Jive coffee bar on Buchanan Street for lunch. Tony said it was the hippest new place in town. I had a bottle of warm Fanta and a plate of cheese sandwiches with crisps and watercress on the side. Mum had a slice of cold quiche. The sweet trolley was wheeled to our table by a waitress dressed in yellow bell-bottoms and an orange-and-brown striped jumper with a heart-shaped hole cut round her belly-button. Mum had a meringue and I chose a vanilla slice filled with custard and topped with a thick layer of icing.

I was shovelling the last of it into my mouth when I nearly choked with shock. I sat frozen to the spot, my legs jolting involuntarily. I strained, peering closer to make sure I wasn’t imagining it. I wasn’t.

– M-m-Mum, I mumbled, that’s Dixie Deans over there, drinking coffee.

– Who?

– Dixie Deans, 117 goals in 148 appearances for Celtic, including eight as a substitute.

Although I went to a Proddy school, I supported Celtic because they had won virtually everything as far back as I could remember. It meant being called a ‘Tim lover’ and a ‘Fenian’ but it was a small price to pay. Some of my classmates supported Celtic as well, until Rangers won the league the previous season, for the first time in a decade, then they started supporting Rangers, but I stuck to my guns. I didn’t care what anyone else said, Celtic were still the best.

– OK, calm down, Mum said softly. Don’t get over-excited.

– But he’s here. In the same room as me, Mum. I can’t believe it. I’m in the same room as Dixie Deans.

– Why don’t you go and ask him for his autograph? she suggested.

My head felt light and, momentarily, I lost my peripheral vision. I thought I was going to pass out.

– I couldn’t. I couldn’t just walk over and talk to Dixie Deans.

– Of course you could. I’m sure it happens to him all the time.

She dug into her handbag and produced a pen and a piece of paper. I remained frozen to my seat.

– Do you want me to ask him?

I panicked. If there was one thing more mortifying than approaching Dixie Deans in a restaurant full of people, it was having your mother do it for you. I grabbed the pen and paper and steeled myself.

All the way home I cradled the autograph like it was a rare antique. I held it up to the light, scrutinised it from different angles and gazed at it with awestruck deference. That evening, I breathlessly recounted the episode. Something genuinely exciting had happened to me and it didn’t matter that Dad and Tony were trying to wind me up about it. Tony wasn’t interested in football and he was always taking the piss out of footballers for being thick.

– No-one’s going to believe you actually met Dixie Deans, he laughed.

– Yes, they will, because I’ve got his autograph to prove it.

– That’s what I mean. No-one’s ever going to believe that he can write his name.

Dad and Sophia, my elder sister, were laughing like drains and Mum kept telling them to stop teasing me.

– Actually, I’ve got some good news of my own, she announced suddenly.

Everyone turned their attention to her.

– Oh, yeah, what’s that, love? Dad asked.

– I got a letter from Cardonald College this morning. I’ve been accepted as a mature student to study psychology. I start next term.

For months Mum had been talking about how she wanted to do a part-time college course, because she said she wasn’t using her brain working at the Post Office. Dad couldn’t understand why she felt she had to use her brain, as long as she was bringing money into the house.

I didn’t see why anyone would want to go to college – it sounded just like school – but I couldn’t help thinking Dad was over-reacting. He got angry every time a new college prospectus arrived by post and he complained about the mess whenever he found one stuffed behind a cushion on the settee or lying on the bathroom floor. But he made much more of a mess, leaving his old newspapers and dirty laundry everywhere. The prospectuses were just glossy little booklets that hardly took up any space at all.

When Mum made her announcement, Tony, Sophia and I all kissed her and congratulated her, telling her that she had done really well. We knew how much it meant to her. But Dad didn’t say anything. He just sat there silently and continued to eat his dinner.

2

Aunty Betty was an unlikely cold warrior. To us she was the most indiscreet woman in Bonkle, but to Britain’s security services, facing down the dreaded Soviet threat, she was a treasured military asset – a skilled black operative capable of spreading malicious and destabilising misinformation among the enemy in the event of a threatened nuclear strike.

In 1948 she set the modern benchmark for military-grade gossiping. In a controlled experiment at the government’s weapons research laboratory at Porton Down, she was told ‘in the strictest confidence’ by her best friend, Ina, that the minister’s wife was having an affair. The pair were locked in a hermetically sealed, lead-lined bunker fifty metres below ground level with no means of communication in or out, and yet, within half an hour, thirty of Betty’s closest friends had the information.

I cast my eyes skyward and sighed. Tony had a million of these stories, each more fancifully embroidered than the last, and I never believed a single one. Someone of my tender years should have been a saucer-eyed sitting duck for his fables. My childhood self wanted to believe they were true, God knows I needed the excitement, but I just couldn’t trust him. I couldn’t trust anyone, not since the whole Santa Claus thing turned out to be such a grand lie.

I’d felt such a gullible fool, watching Dad furtively bundle a Raleigh Tomahawk from the back of the car into next door’s garage on Christmas Eve. The following morning we all feigned euphoric surprise when, lo and behold, it appeared at the foot of my bed, sprinkled with glitter (reindeer dust) and bits of cotton wool (Santa’s beard).

To his credit, Tony had tried to convince me that it was all a grotesque misunderstanding. Santa did exist, it’s just that he wasn’t able to make it to our house that year. He was on strike – out in sympathy with the miners – and besides, what with the whole OPEC crisis, how was he going to afford enough petrol to drive his sleigh all the way from the North Pole to Gower Street?

But by then the mask had slipped. Believing in Santa was an act of faith and, once questioned, it began to unravel like the cheap Woolworth’s wrapping paper from the Oor Wullie annual which, I happened to know for a fact, had been lying stashed at the back of Mum’s stockings drawer for weeks.

Until then I had been Tony’s most consistently impressionable foil. For him it added an intriguing dimension to conversing with a sibling six years his junior, knowing that I could be hoodwinked effortlessly by whatever whimsy was passing through the transept of his mischievous imagination. After finding out the truth about Santa I was a twisted knot of cynicism, batting back each of his confections more astringently than the last.

Christmas was eight months ago but there still wasn’t a day when I wasn’t eaten up with the duplicity of it all. Even if the Santa thing had never happened, I doubt I’d ever have believed that Mr Gibb, two doors down, was really Evel Knievel.

For a start, he was about a century too old. Evel Knievel was chiselled and athletic and he wore white, star-spangled jumpsuits. Mr Gibb was lanky and stooped with thinning, grey hair combed back and Brylcreemed into place with parade-ground precision. He had a florid, parboiled complexion and a wardrobe that consisted entirely of shiny polyester suits and shirts from Brentford Nylons. Evel Knievel travelled the world performing death-defying motorcycle stunts. Mr Gibb worked in a factory in the Hillington industrial estate making paint for oil rigs.

– Tony, yer talking pish, was my considered verdict.

– Have you ever seen Evel Knievel without his helmet on?

I had to concede I hadn’t.

– So how come he’s Evel Knievel and not Evel Gibb? I demanded.

– He doesn’t want his bosses knowing his true identity. He reckons that if the whole jumping-over-double-decker buses thing doesn’t work out, he’ll always have a job mixing paint down at Stenhouse & Barratt’s.

Tony was sitting on the ledge of my bedroom window, smoking a Player’s No. 6. His chin was resting on his raised knee while his other leg dropped carelessly against the white, stippled façade of the outside wall. It was the end of a long July day, during that short interlude when dusk and darkness are indistinguishable, when the moon is battling for supremacy with the retreating summer sun.

My brother habitually chose my bedroom in which to smoke because his faced onto the street and there was the danger that one of the neighbours would see him and tell our parents. The bedroom I shared with Sophia backed onto a network of small, uniformly manicured gardens, adorned with goldfish ponds, gnomes and stone-clad wishing wells. The driveways were populated with second-hand Ford Anglias and Datsun Cherries, wax-shined and scrupulously maintained by their proud owners.

We were one of the last families to move into the estate. It was the proudest day of Mum’s life when she took possession of the house keys and was able to describe herself as an ‘owner-occupier’. The builders’ blurb for the new house had promised a ‘modern, well-appointed, three-bedroom, semi-detached villa with a split-level lounge, new kitchen with appliances, fitted wardrobes and a patio garden’.

It was certainly modern, I’ll give them that. Two years previously, the estate had been the muddy, dilapidated remains of a tyre factory. It was also factually correct to say that our house had three bedrooms, in that all were just about big enough to accommodate a bed, but physical separation of space was merely a concept, such was the flimsiness of the walls, no respecters of sound or smell.

Over the years, we would become intimately acquainted with our neighbours, their intrigues and manoeuvrings, their sanitary routines and their dietary preferences. They, no doubt, had a similarly detailed dossier on us but there was an unspoken rule that intelligence obtained inadvertently through the connecting walls was inadmissible in neighbourhood gossip.

While it was Mum’s dream home, the rest of us were unconvinced. Dad moaned about the thirty-quid-a-month mortgage, the cheap fabric of the building – a fortnight after we moved in Sophia put her foot though the bathroom door during an argument about the provenance of a hairbrush. He moaned about the garden, whose thick clay soil didn’t absorb water and which flooded every time it rained, and about the snooty neighbours who, he said, walked like they were softening up a caramel between their arse cheeks.

Sophia moaned about the lack of anything to do and the fact that none of her friends lived nearby. She also complained about having to share a bedroom with me. In our previous home – a rented tenement flat in Pollokshaws – all three of us had shared a room. Now we had an extra bedroom, Mum decided that Tony should have it. Sophia complained bitterly, claiming that she was fourteen and deserved some privacy, but Mum said Tony needed a quiet space for his studies. After he had finished his Highers, she promised, Sophia could have her own room.

I pointed out that Tony was two years older, so if anyone deserved his own room, it was him. Not that I was suggesting I’d rather share a room with Sophia, I was merely highlighting the weakness in Mum’s argument. She said it was different for girls but she didn’t explain why.

Through snatches of overheard conversation, I managed to elicit that Sophia was going through ‘the change’ but quite what that entailed was never explained. I racked my brain. What could it mean – change of heart, change of pace, change of clothes? I couldn’t help but notice her physical development. Gone was the untamed boyishness of her youth, which had been replaced with a slimmer, elegant femininity. Her slightly chubby face had a new angularity and her flat, featureless upper body had acquired curves and bumps that now required accommodation in extra items of underwear.

It was also apparent that an increasing amount of the household conversation now revolved around Sophia’s mood. Nothing was to be done to upset Sophia. Everything should be done to accommodate Sophia – though, of course, she still played second fiddle to the prodigal Tony.

As I lay in bed, I could see the silhouette of my brother’s handsome, aquiline features against the night sky. He had changed too. He was mature now. It wasn’t so long ago that we were inseparable, sharing the same interests and preoccupations. But he started growing away from me and I couldn’t keep up. The more I tried, the more intolerant he became of my pitiful attempts.

He pinched the remains of the fag between his thumb and index finger and dragged hard on the last half inch of tobacco. Thin jets of grey smoke streamed from his nostrils as he flicked the misshapen filter and watched it fly in a high parabola, then crash land on the paving below. The following morning he would be up before Mum and Dad, scurrying about in the garden, collecting his discarded butts.

I always enjoyed it when Tony thought he heard the whining creak of a floorboard and frantically waved his arms like a windmill in a storm to disperse the clouds of smoke. When he was confident that neither of our parents was on their way upstairs he closed the window and returned to his own room.

The following day, after church, I went round to see Wally to show him my Dixie Deans autograph. In Govan, where money was in short supply, Wally’s family had less than most. Fungus peppered the walls of their tenement flat in vast, impromptu murals. What was left of the wallpaper sagged forlornly, as though years of exposure to such a fetid environment had robbed it of the will to adhere to the walls. The living room carpet, permanently littered with empty Irn-Bru bottles and oil-stained motorbike parts, had a tackiness, which slowed your step. It was a felonious collage of brown and mustard hues, for which the designer responsible should have felt considerable remorse. Something smelled strongly of rotting onions, and my money was on the carpet.

Wally’s dad was a wiry drunk who had the soggy stump of a Capstan Full Strength adhered permanently to his bony, tar-blackened fingers. Every night, with metronomic regularity, he staggered home from the local bowling club – where the subsidised drink was a quarter of pub prices – filling the streets with a criminally tuneless rendition of ‘The Old Rugged Cross’.

That day, a Sunday, Wally’s dad had been drinking all morning and was lying comatose on the sofa, killing time until the pubs opened.

As we sat on the floor half-watching The Golden Shot on their old black-and-white telly, I showed Wally my Dixie Deans autograph. Wally was a Pape so I knew I’d be on safe ground, but he didn’t show the level of enthusiasm I’d been hoping for for. Instead, he glanced at it uninterestedly and mouthed some forgettable platitude. I shouldn’t really have expected more. Wally was more interested in motorbikes than football.

Besides, his attention was now focused on Handbag and Holdall, two of his elder brothers, who were standing over the old man, crumbling an Oxo cube into his gaping mouth. They stifled conspiratorial laughter, willing him to wake up. Occasionally he stirred and coughed when one of the crumbs caught in his throat but, defiantly, he remained asleep.

After a while, they became bored, but Handbag had an idea. He rubbed part of the stock cube onto his dad’s lips and chin and then roused Daphne, the family’s obese and sickeningly malodorous mongrel bitch from a urine-stained cushion, which served as her bed. Daphne was dragged across the carpet, her legs buckling under the weight of her monumental behind, and her nose was pushed against the face of her drink-sodden master. She sniffed around his mouth and, recognising something edible, she began to lick, covering the bottom half of his face with a white film of canine saliva.

Once she had removed all traces of Oxo cube from his face, she began to probe the inside of his mouth with her searching pink tongue. We were doubled up with laughter, and yet, despite the din, old man Rafferty remained soundly in the Land of Nod.

Holdall decided to take more radical action to try to get a response. He lifted a box of matches that was lying at the foot of the sofa. He lit one and held it under his father’s bare foot. The old man winced and pulled his foot away from the flame but then simply grunted, rolled over and continued to sleep. Holdall held the match under his other foot for ages until smoke started to rise from the hardened skin at the back of his heel.

Suddenly, his dad leapt up, clutching his foot and cursing the air blue. He stopped abruptly, swaying, confused and irascible, surrounded by laughing, baying tormentors like a bear in some degrading circus act. All the time his mouth chewed and, slowly, the expression on his face began to change from bewilderment to horror, as the taste of the Oxo cube registered. As the taunting grew louder he doubled over, retching and dribbling brown spit down his shirt and onto the carpet.

Now fully conscious, he reached for the closest thing to hand – a thick, rusting motorcycle chain – and lashed out. The brothers judged they had gone too far and made a beeline for the hallway, none of them stopping to observe social niceties, like ensuring the safety of their guest. I was left to follow in hot pursuit and, as I ducked behind the living room door, I felt the full weight of the chain crashing against it.

I was in the back yard, crouching next to Wally in one of the midden huts before I paused to draw breath. My heart was pounding violently. The others had run off in different directions and were nowhere to be seen. I was so terrified I could barely speak but Wally sat on the ground, resting languidly against a bin, laughing quietly to himself.

– Won’t he kill you? I asked.

– Nah, said Wally dismissively, he’ll never remember in the morning.

I couldn’t help wishing again that my life was more like Wally’s. There was a swaggering arrogance about him and his brothers that I wanted to emulate. Of course, Mum didn’t want me associating with him because he was common. On occasion Dad stuck up for him, saying that he was just a harmless kid from a poor family, but Mum always won that battle.

Whatever thrall suburban respectability held her in, I didn’t get it. I had just narrowly escaped bearing the full force of a ten-pound motorcycle chain thrown by a drunk whose feet had been set on fire. That was excitement. The most thrilling thing that ever happened in our house was when a soufflé collapsed. There was a thudding ordinariness about my life and no amount of fictional web weaving on the part of Tony or anyone else was going to change that.

3

We hadn’t yet arrived at my cousin Billy’s wedding and, already, the day had the makings of a disaster. A tension had been developing all morning, with a series of frosty exchanges between Mum and Dad, followed by an entirely silent car journey, and now we were lost.

Each of us had our own reason for not wanting to be there. I was dreading the first outing of my new suit – the one that made me look like I had raided Prince Edward’s wardrobe. Mum was angry that Dad hadn’t forced Tony to get a haircut (now eighteen months and counting since his last visit to the barber), compounding her embarrassment at being seen publicly with him in the controversial flared suit trousers, platform shoes and Rubettes cap ensemble. And Sophia was grumpy because she was always grumpy – something to do with the mysterious ‘change’, I presumed – and Dad was still simmering about Mum going to college.

All these grievances combined, however, failed to match the strain generated by five of us crammed into a Mini Clubman, driving around Coatbridge on a pissing wet afternoon trying to find the Church of the Sacred Heart with the seconds ticking down to three o’clock.

– For God’s sake, Christine, why didn’t you get directions before we set off ? Dad demanded, driving us up yet another dead end.

– He’s your bloody nephew, Robert.

– Why don’t we stop and ask someone for directions? I suggested, thinking I was doing the right thing.

– No-one asked for your opinion, so keep your mouth shut, Dad snapped.

After another ten minutes of aimless meandering, we stopped and asked someone for directions.

It had been a full week since Mum’s announcement about college, and Dad remained silently brooding. His reaction had surprised us all. He was always going on about how he’d never had a proper chance at school and that, if he had his time again, he’d stick in. Now it seemed his concern for the value of education didn’t extend to Mum. After she had dropped the bombshell at the dinner table, Sophia and I were sent to bed early, but we sat at the top of the stairs listening to our parents arguing.

– What about your job at the Post Office? Dad demanded.

– Helen says I can go part-time, and with my student grant we won’t be any worse off, Mum explained, I thought, quite reasonably.

– What about the kids? Who’s going to look after them?

– The kids are at school all day.

– What about in the evenings, when you’ve got your nose in a pile of books?

– I can study after they’ve gone to bed, and you can always help out.

– Don’t you think I’ve got enough on my plate? Dad demanded, his voice raising a decibel.

– I’ve done night classes before and there wasn’t a problem then.

–That was just a hobby, Christine. It didn’t affect your life. This is your life – me, the children, the house.

It went on like that for hours. Just when we thought Dad had run out of things to complain about, he forced Mum down another cul-de-sac of mangled logic. She could better him in an argument at the best of times and, usually, he would quit while he wasn’t too far behind. But it was obvious there was nothing Mum could say, short of agreeing to scrap the whole idea, that was going to satisfy him.

We arrived at the chapel with minutes to spare and took our seats at the back, on the groom’s side. It was a modern, functional building in the middle of a grim housing estate and it had garish, stained-glass windows whose biblical scenes looked like they had been designed by a Soviet committee. It was dominated by rows of wooden benches, many of which had been defaced by penknife carvings and graffiti. Its centrepiece was a painted ceramic statue of a hooded Christ. One of the outstretched, blood-stained hands had broken off, leaving a small wire stump. It occurred to me how different everything was from the sobriety of our own church.

Billy was the son of Dad’s eldest brother, Christopher. After Christopher there was Vincent, who lived in America, then Frank and then Dad, the youngest of the four. This was the first time in years that we had seen any of them. Granny and Granddad had both died before I was born, and Dad never really kept up with the rest of his family. He rarely even talked about them. The only thing I knew about his upbringing was that he was born and raised in Leith and that he’d left school at fifteen to work as a commis waiter in a hotel in Edinburgh, where he met Mum.

I often wondered why we never saw any of Dad’s side of the family. He said it was because they all lived in Edinburgh, which was too far to travel, particularly as he worked nights. Tony said that was bollocks, Edinburgh was fifty miles away and it would take us an hour to get there in the car. He said the real reason we never saw them was because Mum thought they were common.

Common-ness was a big thing with Mum. It governed every aspect of our lives and yet it had no consistent definition other than as an arbitrary set of conventions informed by her sense of propriety. Attempting to second-guess what was and wasn’t common was never simple. Arriving late was common but so was arriving early. Talking loudly was common as was talking quietly. It was often difficult to pitch your voice at just the right level. Spitting, sucking loudly, whistling and eating with your mouth open were all common; in fact any oral activity was a minefield of potential social indiscretion.

Other equally common items included – in no particular order – tattoos, Catholics, blonde hair, platform shoes, British Home Stores, Val Doonican, HP sauce, On the Buses, untipped cigarettes, Lena Zavaroni, football supporters, Wimpy restaurants and anyone from Maryhill.

I was at the end of our row of pews and so I could see all the way down the aisle to the altar. Billy kept glancing back nervously. I was struck by how young he looked. He couldn’t have been much older than Tony. He and his best man were dressed in identical, standard-issue kilts and short black jackets with all the trimmings, their heavily lacquered rooster cuts, pasty pallor and rampant acne fatally compromising whatever romantic image they might otherwise have projected. There was a dispiriting drabness about the guests and it hadn’t escaped my notice that, of all the children present, I was the only one wearing a suit.

The event was in marked contrast to the wedding of Mum’s younger sister, Helene, which remained, by far, the grandest occasion I had ever attended. There, the male guests had worn grey morning coats, and the female brightly-coloured dresses with flamboyant hats. At the reception, the ladies were given little baskets of sugared almonds with sprigs of heather tied to them and the men got miniatures of whisky. Dad didn’t drink, and so he gave his to me, saying I could start a collection. A year on, it remained a collection of one.

Suddenly the organist struck up the first notes of the bridal march and Billy’s bride, Evelyn, appeared at the rear of the church, alongside her father. She was wearing a plain, white silk dress with no frills, which barely reached beyond her knees. She had a pained expression on her face, as if she was about to cry. As she passed our row, Mum whispered something to Dad about her stomach. Dad’s face hardened and he whispered back, sternly, that this was not the time and she should keep her comments to herself.

When the bride reached the altar, the priest welcomed everyone to celebrate the joining together in marriage of the happy couple. There was no warmth in his voice and his face remained expressionless. He paused for an uncomfortably long period when only the shuffling of bottoms on seats and the occasional cough broke the silence.

– May the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ and the love of God and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit be with you all, he said solemnly.

– And also with you, the congregation muttered in unison.

I’d never heard people joining in like that at church before.

– Lift up your hearts, said the priest.

– We lift them up unto the Lord, said the congregation.

As I looked along our row, I was surprised to see Dad mouthing the responses.

– Let us give thanks to our Lord, the priest continued.

– It is right to give him thanks and praise, Dad replied, along with the rest of the congregation.

I leaned over to Mum.

– How come Dad knows the words? I asked in a whisper.

– I suppose because he remembers them from mass when he was a wee boy, she replied.

– What’s mass?

– It’s the Catholic Church service.

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Dad, a Catholic? I sat in a state of shock, like Joe Bugner had just landed an uppercut on my chin. Why had no-one told me? Who’d have guessed? If Dad was a Catholic, that made me one as well, sort of. I could hardly contain my excitement.

I’d always wanted to be a Catholic, just like Wally. The stories he told us about St Bernadette’s made the hairs on the back of my neck stand on end. Apparently, it was named after this woman who lived in the olden days, who kept seeing this ghost who looked just like Jesus’s mum, Mary. Bernadette didn’t run away when she saw the ghost, so they turned her into a saint. According to Wally, St Bernadette’s was run by a priest called Father Byrne who made you do something called confession, which meant sitting in a box and telling him about all the times you’d thought about women in the nude. If you didn’t, he could read your mind and he’d make you wash his car and run to Carter’s, the newsagent’s, for his fags. That was called penance.

With religion, like everything else in life, I was saddled with the boring, strait-laced alternative. Every Sunday, I was dispatched to the local Protestant church to listen to Reverend. MacIver droning on endlessly about tolerance, forgiveness and divine love.

Sophia and I were the only members of the family who still went to church on a fairly regular basis. Dad was strictly weddings and funerals. Mum attended occasionally, and Tony had stopped going altogether because Karl Marx said religion was the opium of the masses. Dad said he’d have changed it to the valium of the masses if he’d ever had to sit through one of Reverend MacIver’s sermons.

To think that I’d spent all these years yawning in the pews at Pollokshields Parish Kirk when I could have been down the road at St Bernadette’s marvelling at Father Byrne barking threats of retribution and eternal damnation. There was something exciting and dangerous about the Catholic Church. It had the cool menace of a Saturday night horror flick with all its sins and punishment. It had mortal sins, venial sins, capital sins, contrition, excommunication, penance and reparation. It also had great props – conception beads, scapular medals, holy water, communion wine – which Wally stole for his dad when he was an altar boy – wall crucifixes, mounted crucifixes, medallion crucifixes and more icons than you could shake an archiepiscopal pallium at. The Protestant Church had pews and hymn books.

If Wally missed confession, Father Byrne would go down to his school, pull him out of class by the ear and beat him with a stick. If I missed Sunday school Reverend MacIver always said Jesus would forgive me. Father Byrne drank the blood of Christ and issued warnings of souls being trapped in purgatory for eternity. Reverend MacIver judged the best drop scone competition at the Women’s Guild annual fete.

After the wedding service, Mum made a point of commenting on how Billy and Evelyn had not posed for official photographs outside the church.

– Leave it alone, Christine, Dad said curtly.

We drove the half mile to the Coatbridge Knights of St Columba Social Club where the reception was being held. Most of the other guests walked and, by the time they arrived, they were wringing wet.

The club was housed in a windowless, brick-built box on a piece of waste ground at the end of a long dirt track. As we entered by the reinforced steel door, we were hit with the bitter smell of alcohol and stale tobacco smoke. Inside, the yellowing walls were decorated with streamers and tinsel that looked like the limp remnants of a long forgotten Christmas party.

The guests were to be seated on benches along rows of paper-cloth covered tables – those invited by the groom down one side and those by the bride down the other – with a dance floor separating them. The tables were adorned with paper platters, piled high with sausage rolls, meat paste sandwiches and Scotch pies. There were also paper cups and bottles of Irn-Bru. As we took our seats, a waitress, not much older than me, told us that crisps were available at the bar.

We sat down at the same table as Uncle Christopher, Uncle Vincent and Uncle Frank and their wives. Billy and Evelyn were on the other side of the hall alongside her parents. When everyone was seated, Evelyn’s dad – a thin, frail-looking man – stood up and said in a faltering, barely audible voice, that he wouldn’t take up too much time, but that he wanted to wish the happy couple well and that everyone should enjoy themselves. All the men on our side jeered and heckled – principal among them Uncle Christopher and Uncle Frank – urging Billy to make a speech. Someone shouted something about the lead in Billy’s pencil and everyone laughed. I figured they were just teasing him and that it must be good-natured but the guests on the bride’s side, including her three fierce-looking brothers, scowled, and Billy sat, scarlet-faced, staring at the floor. Mum directed an acid-drop stare at Dad who shrugged, as if to plead innocence by non-association, as his brothers nudged and egged him on to join in the banter.

We had just started eating the sandwiches when Uncle Frank stood up.

– Right, who’s for a bevvy? he asked the group.

Most of the men ordered half and halfs – whisky with beer chasers – and most of the women ordered Bacardi and Coke. Mum said she was driving and would have a tonic water. Dad tried to say he didn’t want a drink but Uncle Frank was having none of it.

– Aw, come on, Rab. Ur ye a man or a moose?

Dad looked embarrassed and said he would have a pint of lager. When Tony was asked what he wanted, he hesitated.

– He’ll stick with Irn-Bru, Mum said pointedly.

– Aw, let the lad have a beer, Uncle Frank implored. It’s his cousin’s wedding.

– He’ll have Irn-Bru, Mum said more forcefully. He’s sixteen, Frank.

Dad managed to nurse his drink for about an hour, by which time all the others at the table were on their fourth or fifth and were considerably less lucid. Uncle Frank’s demeanour had become challenging, urging Mum to ‘lighten up’ every time she winced at his near-the-knuckle humour. Dad shifted on his seat and kept a nervous grin stapled to his face.

Mum sat next to Uncle Vincent and Aunt Sadie, who had travelled all the way from California especially for the wedding. The last time she and Dad had seen them was before I was born. Now naturalised Americans, they stood out from the other guests like well-hammered thumbs. Uncle Vincent looked well-fed, his rotund belly penned inside a pair of powder blue slacks by a matching, tight-fitting polo-neck sweater. Over that he wore a cream blazer and the look was accessorised with a pair of white moccasin shoes, a chunky gold necklace and a pair of matching gold sovereign rings, one on either hand.

Uncle Vincent had built up a successful used-car business in Santa Monica and, clearly, he had a healthy respect for his achievements. He spent a good deal of time telling anyone within earshot that you hadn’t lived until you’d driven a 1949 Buick Roadmaster through the Sierra Nevada mountains and how he’d recently made a two hundred per cent mark-up on a 1972 Oldsmobile 442 convertible.

Sadie was entombed within a turquoise brocade kaftan with decorative gold piping. The only visible part of her was a shrivelled, sun-toasted, peanut-shaped head, which was topped by a thinning peroxide mane. She sat swigging long vodkas, adding conscientiously to a collection of lipstick-smeared, American cigarette stubs building in an ashtray in front of her, talking vociferously about ‘the price of gas downtown’ and her favourite ‘mall, Stateside’, in a strangulated accent which sounded like Stanley Baxter doing a bad impression of Mae West.

After the last of the pies and sandwiches were eaten and the plates cleared away, an unremarkable, single-tier cake was carried into the hall which Billy and Evelyn were persuaded to cut, doing so with as little ceremony as they could manage before shuffling back to their seats.

The man who ran the hall then clapped his hands briskly to get people’s attention and announced that, due to unforeseen technical difficulties, the musical entertainment planned for the evening had been delayed. The unforeseen technical difficulties, it later emerged, involved a steaming drunk road manager and the unknown whereabouts of a Ford Transit van. It meant the members of Alice Band – a Smokey tribute act from Airdrie – were forced to make their way to the venue by bus, carrying their equipment on their laps. They eventually trooped in, wet and bedraggled, and assembled their equipment on a small elevation at the top end of the dance floor, immediately below a framed photograph of Pope Blessed John XXIII lying in state.

An uninspiring, but otherwise technically proficient, medley of Smokey hits followed. As the band struck up the opening bars of ‘I’ll Meet You at Midnight’, Uncle Frank formed a delegation of one to the stage to ask if they might introduce some thematic variation to their set. The request did not appear to go down well with the Zapata-moustachioed lead singer – all of five feet three inches in his cowboy boots – who pointed out that they were playing in a ‘poxy shithole’, that their payment for the evening amounted to a case of McEwan’s Export which, after the cost of their bus fares had been deducted, left them out of pocket, and that they would sing ‘whatever fucking songs they fucking well wanted to sing’. Frank pointed out that the singer’s microphone was still switched on and that his outburst had been relayed to all the guests,

The pair then retired to the back of the stage to continue their dialogue. Several times Uncle Frank squared up to the singer – or, more accurately, squared down to him – before being restrained by other members of the band, and several times the singer responded in kind.

Eventually Uncle Frank trooped back to our table to reveal that a deal had been brokered. In return for allowing the band to perform mostly Smokey covers, there would be an interlude where guests would be invited to perform their favourite songs to which the band would provide accompaniment.

After some initial suspicion among the other kids at the wedding, probably on account of my suit, it seemed that I had been accepted into the fold, and they invited me to join them in a game of ‘The Poseidon Adventure’ in which the underside of the long tables doubled as the hull of the doomed vessel. I declined, mainly because the Gene Hackman role had already been taken, but also because I was having too much fun watching the adults.

Dad had left our table and was standing at the bar with his brothers. Now onto his third lager, he was behaving in a way that was as unexpected as it was disarming, rocking back on his heels, blinking purposefully, slapping his brothers on the back and laughing uproariously even though no-one had said anything remotely funny.

Tony, meanwhile, had taken a close interest in one of the bridesmaids. They were locked in a corner of the room, their foreheads almost touching, engaged in intense discussion. Tony appeared to be doing most of the talking while she watched him intently, occasionally throwing her head back, her puffy, pink dress rippling with the force of her laughter. I could see Mum monitoring them closely, and she was clearly not amused. When she spotted Tony’s hand rest on the bridesmaid’s bare shoulder she told me to tell Dad she wanted him to go over and get Tony to stop being so ‘familiar’.

– Tell your mother that he’s a young lad enjoying himself and that she should do the same, Dad said.

– Tell your father he’s no longer a young lad and he appears to be enjoying himself a bit too much, was her response.

I decided to pass on Mum’s request directly to Tony but, as I approached, I overheard him telling the bridesmaid that Les McKeown, the lead singer of the Bay City Rollers, was dead. It was common knowledge at his secondary, he insisted. He had died in a freak accident two years previously after getting his tartan flares caught in an escalator. His death had been hushed up by the band’s management, who feared the adverse publicity might lead to the Croydon Metropole cancelling their gig. Instead the Rollers’ accountant, who bore a passing resemblance to McKeown, had been given a guitar and a feather cut and ordered to take his place.

Despite it being a really big secret, the other band members left clues lying around so that their fans would know the truth. On the cover of their album, Shang-A-Lang, ‘McKeown’ is standing in an upright position – an ancient runic death symbol – and if you played ‘Bye, Bye, Baby’ backwards you could clearly hear the voice of Stuart ‘Woody’ Wood singing: ‘Likesay, Les is pure pan breid man, ken, s’nae real.’

The bridesmaid laughed like a drain. I was confused. Why did she find it so amusing? Even if, as I suspected, the story was one of Tony’s tall tales, it was certainly no laughing matter. If, on the other hand, it was true, hers was a highly disrespectful response. Honestly, I just didn’t get older people sometimes.

Soon it was time for the guests to perform their musical turns on stage, which turned out to be the best bit of the evening. I couldn’t understand why anyone would want to make such a monumental spectacle of themselves, but there was no shortage of takers. First up was a short, inebriated woman with several teeth missing, who introduced herself only as Wee Jean. Despite the presence of the musicians, she insisted on performing an a capella version of ‘Chirpy Chirpy Cheep Cheep’ by Middle of the Road, but she was so tunelessly awful that she was booed off the stage before she got to the bit where she woke up this morning and her mama was gone. I had no idea who she was and assumed she was from Evelyn’s side of the family. She was later exposed as a gatecrasher.