Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

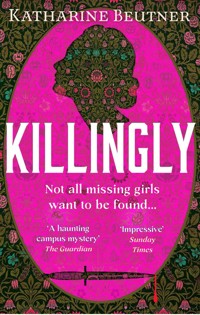

*FEATURED IN SUNDAY TIMES, NEW YORK TIMES, APPLE'S BEST BOOKS, AMAZON'S BEST BOOKS OF JUNE, CRIMEREADS RECOMMENDS AND LITHUB'S TOP BOOKS* 'SARAH WATERS AND DONNA TARTT SQUAD, BUCKLE UP: Killingly is hitting the Plain Bad Heroines place in my heart again' Autostraddle 'Impressive' Sunday Times 'Gothic atmosphere, great period detail and a genuine shock at the end' Guardian 1897, New England. Agnes and Bertha are best friends. Clever, eccentric misfits at an elite college for young women, they study earnestly, write poems for each other and explore the woods around campus at night. One morning, Bertha vanishes. Called down from Boston, renowned missing person expert Detective Higham arrives to find the tranquil college in chaos. A treasured pearl dagger has disappeared from a student's bedroom. The most popular debutante on campus is losing her mind. There are rumours of a ghostly woman at the train station. As he questions the students and teachers, Higham unearths a strange story of doomed love, ambition and tragedy which could shatter the college's glittering reputation forever . . . A gothic, turn-of-the-century campus thriller about female desire, rage and ambition, perfect for fans of TRIFLERS NEED NOT APPLY, THE BINDING and FINGERSMITH . . . * EVERYONE IS TALKING ABOUT KILLINGLY: 'A haunting story . . . will stay with me long after reading' ELIZABETH LEE, author of Cunning Women 'Completely engrossing. Unforgettable!' MARTHA CONWAY, author of The Physician's Daughter 'Beutner is masterful at depicting the intrigue and innuendo of a women's college.Perfect pacing . . . grows increasingly shocking as the pages turn' The Akron Beacon Journal

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 511

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ALSO BY THE AUTHOR

Alcestis

First published in hardback in the United States in 2023 by Soho Crime, an imprint of Soho Press

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2023 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2024.

Copyright © Katharine Beutner 2023

The moral right of Katharine Beutner to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 9 781 83895 925 8

E-book ISBN: 9 781 83895 924 1

Printed in Great Britain.

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For my mother, the artist

–

. . . the science of life . . . is a superb and dazzlingly lighted hall which may be reached only by passing through a long and ghastly kitchen.

—Claude Bernard, An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine (transl. by H. C. Greene), 1865

–

Vivisection is an unmanly crime.

—Alan Mott-Ring, MD, Arlington Heights, MA, in The Report of the American Humane Association on Vivisection in America, Adopted at Minneapolis, Minn., Sept. 26, 1895

–

All classes have some little lamb / Who loves to go to school

—Written on a notecard found in the 1897 scrapbook of Katharine Shearer, Mount Holyoke College student

1

That morning Agnes was drawing the cracked pelvis of a beaver. She had found it in the woods near Upper Lake, where the men had been searching for Bertha. Usually she could collect only chipmunk bones or rabbit or squirrel. She’d never drawn a beaver before.

The men were still searching for Bertha. Agnes had wondered, briefly, what else they might find in the ponds. Perhaps there were other girls who had vanished in the College woods, other bones tangled in the roots of the pines along the grassy edges of the water. The bow of the clavicle, the bowl of the pelvis. She had wanted to see. But it was habit now to keep to herself, to appear as unobjectionable as possible. Mute as the white cross hung upon her wall and banal as the cross-stitched hymns beside it. She’d been spared freckles and red or black hair; hers was dark brown like soaked wood and lay flatter against her head than was fashionable. She and Bertha simply scraped their damp hair back after a washing—because dowdiness was permissible, even godly. Dowdiness had been a shield for them both.

Agnes had a narrow room on the third floor of Porter Hall, a slim little desk and chair designed for the ministers’ daughters who thronged the College. Bertha had fit these chairs well. Agnes herself was not narrow. She was a broad spare girl of twenty, trim but tall and square-shouldered and squarehipped. She never drew self-portraits, though she was a fine draughtswoman in the anatomical mode. She did not wish to look at herself long enough to see the truth of her body, how its overlapping rectangles would sit like bare fenced pastures on the page: Agnes Sullivan, all enclosure.

The girls on her hall usually left her alone, as they had left Bertha alone, because they disliked her almost as much as they had disliked Bertha. They still disliked Bertha, in the midst of their fluttering about her mysterious fate. Their dull antipathy did not bother Agnes. Being alone meant that she could concentrate on her work. But Agnes could not trust, any longer, that she would be left alone. Not after what she had done.

There were certain things Bertha had told Agnes that she might still need to do.

Bertha had said: You must lie. No one knows anything, no one can prove anything. Just us. So you can’t—you can’t give in. You must go on. Be strong.

Bertha said, as she kissed Agnes’s hand: I don’t want you to leave college. But you might have to.

And Agnes said: No. I won’t.

Bertha had been missing for one full day. Agnes bent closer to her sketch. Her pencil feathered in a shadow on the page: the fissure in the beaver’s bone, where its strength had failed.

WHILE AGNES DREW, the Reverend John Hyrcanus Mellish and his older daughter, Florence, stood outside the president’s office in a dark anteroom with thick red carpets that made the place feel muffled, like a silent cavern of some massive body. The building, Mary Lyon Hall, was massive, too—another collegiate Gothic cathedral of rough red stone with a grand clock tower that pierced the gray sky. Florence found herself struggling to breathe inside its bulk. She had been struggling to breathe since the telegram arrived.

Florence and her father had taken the train up from Killingly through Worcester shortly after dawn. The Reverend had dozed against the window while Florence sat straight beside him in miserable anticipation, her stockinged knees thick lumps under her skirt, and drummed her heels against one another to keep blood moving in her feet. They’d changed trains again in Springfield, in a station astringent with the smell of urine even in the chilly weather. A filthy boy had tried to lift Florence’s purse and cried when she shoved him back, and Florence had thought, Nobody is getting what he wants today.

Despite the cold she had taken off her gloves and spent the last hour of the journey picking at the base of her left thumbnail until it bled—an old, bad habit to keep panic at bay. Even in the dim light of the anteroom, now, she could see a brown dapple on the green fabric of her glove.

Mrs. Mead opened the office door herself: a sturdy older woman in a black gabardine dress and a starched blouse with a fringed lace collar that nearly touched her prominent ears. Her gaze was clear and cold. She couldn’t have been more different from delicate Mrs. Ward, who had been the College’s president in Florence’s time. Florence remembered waiting outside Mrs. Ward’s office on a sunny May morning, preparing to make her apologies for her departure from Mount Holyoke after only one year. She had blamed her mother’s poor health, and Mrs. Ward, a trusting soul, had been most understanding.

“Miss Mellish, Reverend Mellish, come in,” Mrs. Mead said, shortly, and waited for Florence to settle her father in a chair. “I am very sorry for your distress. I will tell you all I know.”

There wasn’t much to tell and Mrs. Mead made short work of it. She described the dragging of the lakes and the teams of searchers in the woods: men were walking the banks of the Connecticut River in case Bertha had gone out on one of her long hikes alone and tumbled in; the police were finding a cannon to fire over the water, to raise the corpse with the force of its concussion. Mrs. Mead said “the corpse” quite calmly, with no gulping or quavering. “Of course,” she added, and here she seemed to warm, the way an iron warms in fire, “there is still reason to hope that she has not drowned—that we will find her alive, soon.”

As they exited the building, the crisp air forced a gasp from Florence’s lungs. It was not a sob. She would not allow that.

Her father tugged at her elbow.

“I want to look over the campus,” the Reverend said, his gaze tracking up Prospect Hill, the promontory that stretched along the College’s eastern border. From there, you could command a view toward both Upper and Lower Lake, surveying the manicured trees and impressive structures of the freshly expanded campus. She knew what he wanted. He was hungry to discern Bertha camouflaged like a dryad among those trees and buildings. Desperate to search her out, drag her away from the College, just as Florence had once been dragged away.

“She’s not here,” she whispered, knowing he wouldn’t hear.

But it was easier to obey than to argue, most of the time. They made their slow way to the bridge across the brook at Lower Lake, and with each step Florence heard Mrs. Mead’s voice. The corpse, she thought, the corpse.

Even in her time at the school they’d told the story of the Lady of Lower Lake, a senior so distraught over her failing grades that she’d flung herself to a hanging death from this bridge while stabbing a dagger into her own heart. As a young woman Florence had thought this tale comically baroque, especially its ending—the voice of the dead girl echoing from beneath the bridge when a classmate crossed it. Help me, the girl had cried, I’m down here, while her body cooled in the pond water.

As they crossed the bridge now Florence felt as if her whole body had opened wide like the bell of an ear trumpet, attuned to every sound. A kind of listening that stalled the breath. Once Florence had been practiced at this kind of listening. She had imagined, more than once, how Bertha would sound when pleading for help and what she would do to rescue Bertha. She’d spent the train ride from Killingly rehearsing those visions in new detail. Over and over she’d enfolded that imaginary Bertha in her arms, smelled the grassy tang of sweat along her hairline, squeezed her fierce little body—and in every fantasy Bertha would finally struggle free of Florence’s arms and pat Florence’s cheek and smile, just as she had as a baby.

But no sounds came from below the bridge. Just absence, Bertha’s absence, echoing.

Florence’s father was a husk beside her. He clung to her round arm and puffed weak steam into the air as they ascended the slope. Once he had been an imposing man, though he had never been the sort of minister who thundered from the pulpit. Instead he’d merely looked at you with those flat brown eyes, looked and put his hand on your shoulder, and pressed a firm thumb into the divot below your collar-bone. He had been compelling.

On this campus he drew eyes only because he was a man and Bertha’s father. In the hours since they’d learned that Bertha was gone, the young women of Mount Holyoke had begun creeping around the cold campus with books clasped to quivering bosoms. The girls directed polite smiles at the Mellishes, but their eyes showed wide and white as Florence and the Reverend passed by. She could almost hear their silent prayers: for Bertha’s safety, of course, but really to ward off loss and threat. That Sunday’s mandatory prayer meeting would have an unusual fervency and more clutching of hands than was common. At church, Bible study, their women’s society meetings—all day the girls would pass tremors from palm to clammy palm.

Florence and her father limped up the walk to the grand gazebo at the top of the hill, another addition. Empty now, but big enough for ten girls to picnic under its shingled roof, or twenty if they were cozy. Florence had heard a girl call it the Pepper Box. The Reverend leaned against the gazebo’s steps to catch his breath, and Florence turned away to look out over the campus. The morning sun softened the harsh shapes of the new buildings. If she had not been compressing an endless shriek in her belly all would have appeared tranquil and safe. The boathouse, the two tree-lined avenues and winding gravel paths, the wrought iron lampposts, the few streets of South Hadley past the College gates—and then the woods rolling endlessly into the distance, and Bertha lost somewhere within them.

2

The message from Mrs. Mead arrived at the rooming house at nearly eleven that night. They’d turned down the late supper the lady owner, Mrs. Goren, had tried to press upon them. In her small still room, Florence had been trying to read a book of poems and feeling her attention skitter off the page. The peal of the doorbell startled her up and into her father’s room, where Mrs. Goren hand-delivered the message and hovered to hear its brief contents: Some news, come quickly.

The Reverend lectured through the short carriage ride back to campus. He was trying to tell Florence that she should not worry overmuch. Bertha’s disappearance was a matter of faith, like any trial. “Florence,” he said, “if God wills that she be found, she will be found. We must not fail in our duties because our afflictions increase. God blesses the open-hearted.”

Florence was no defiant agnostic, as Bertha was. Bertha liked to flash her eyes covertly at Florence during John’s tirades about the Satanic malignancy he saw in modern society and the duties of a faithful congregation. Bertha liked to question her father endlessly on what she called “dogma”; Florence preferred to think of God as a light so powerful not even the Reverend’s sins could blot it out. But to hear her father make himself a martyr, to cast Bertha as a sacrifice in service of his piety—

“We are not living in a parable, Father. She’s in danger. She could be sick. Someone might have taken her. I won’t fold my hands in prayer when I could be searching—”

“Bertha,” John said out of shocked habit, used to rebuking the other daughter for irreverence, then caught himself. “That is—Florence—”

“Don’t speak to me,” she said, quietly, and tucked her gloved hands away when he fumbled to take one in his own.

The anteroom was empty, their footfalls deadened by its thick carpet. Mrs. Mead looked up as they entered her shadowy office. She was alone; she was frowning. “Reverend, Miss Mellish. I won’t waste your time with pleasantries. A report has just come in of a girl in Boston, at the City Hospital, calling herself Bertha Miller. I have no other information. If you can travel to Boston now, the police there will take you to her.”

Dread and relief thrashed around in Florence’s chest like a pair of stunned fish. “Of course,” she said, “we’ll leave—”

“No.” John looked to Mrs. Mead. “I will go alone. Dr. Hammond will be here soon. He will direct you.”

Henry Hammond, their family doctor, was the first person her father had contacted when the telegram arrived from the College about Bertha’s disappearance. The Reverend had ordered a bewildered delivery boy to go to Hammond’s house, to deputize the doctor to seek out the town sheriff while they went straight to campus. Florence had been left to pack furiously while John sat reading his Bible, seeking what guidance it could offer in the case of a lost child. Now she was to stay here under Hammond’s direction while her father went to rescue Bertha?

Florence’s feelings were scattered and terrible, like the mess of little foul creatures that scuttle out from an overturned log on the forest floor. She had to go to Boston. She had to.

“You’ll need me to help.” Her throat clotted. “Bertha will need me.”

“Florence,” the Reverend Mellish said. “No.”

“I must know if—”

“Florence.”

She looked to Mrs. Mead for support, but the woman’s expression was opaque—no motherly comfort to be found. Florence wanted to howl. But instead she stood with eyes downcast beside her father as he made arrangements with Mrs. Mead to travel alone.

Florence accompanied the Reverend to the tiny Holyoke station to catch the three A.M. Boston & Maine and half lifted him up the rail coach’s narrow steel steps with the help of the timid young policeman who’d driven them. The skies were black as tar and the platform dim and quiet, lantern-lit.

She returned to the rooming house and tried to rest. In her rattled dreams circled specters of Bertha’s face: A Bertha with bared teeth and wildcat eyes, like her uncle David in the asylum just before his death. A Bertha, anguished, with some criminal’s hands on her dear body. A white-faced Bertha whose closed lids were sluiced with stream water and hair thickened with a coronet of muddy leaves.

AGNES DID NOT DREAM that night—or if she did, we cannot see it. Her mind was segmented as the chambers of a shell and similarly armored. Unless we mean to pry her open, oysterlike, there are things we cannot know about Agnes Sullivan until we have traversed those chambers.

There were many things no one at Mount Holyoke College knew about Agnes.

That she was born in a skip behind the factory where her mother Nora wove cloth. As a baby Agnes had been unrewarding, silent and stiff in Nora’s arms.

That her sister, Adelaide, was born in Agnes’s own small bed, not the one Nora sometimes shared with her sot of a husband. The sisters would share the bed until Agnes left for college. Slowly, she would grow accustomed to Adelaide’s body alongside hers, the only embrace she’d ever welcomed besides Bertha’s. When Agnes was alone in the room—which was rare—she would sometimes strip back the thin sheet and curl herself into the bloodstain Adelaide’s birth had left on the mattress ticking, like the print of a massive spread-winged bird, and spread her fingers out upon it.

That their father had died of his habitual drunkenness when Agnes was seven and Adelaide four, with two babies born dead between them. Her mother didn’t have the money to bury him, so Agnes had to help carry him down the tenement stairs from their third-floor room and roll him into the gutter, where the early morning patrol would haul him away for burial on the city’s charity. Two days later Agnes overheard the neighbor women murmuring about how long the city kept bodies waiting to be claimed. She had despised her father, but for four months she had nightmares about his round white belly puffing in some city morgue basement, his fingers swelling, his red beard inching out into tangles. Then the nightmares stopped and she hardly spared him a thought again, asleep or awake.

That Agnes learned on charity, just as her father was buried on it. She had been the best student in her grade in the local public school and won small scholarships for her recitations: nothing extravagant, but enough to pay for Sunday beef dinners during one cold winter and to buy her and her sister new boots in another.

That Miss Kelly, a once-Catholic Congregationalist who lived up the lane in the nicer part of their neighborhood, had read the tiny item about those scholarships in the Herald and had looked up Agnes’s mother to offer her guidance. Miss Kelly was plain and small and terribly freckled, but to Agnes she also seemed bright against the drab walls of their apartment, lit up by her calm certainty in her own talents, her earnest desire to better Agnes, to school her. It was Miss Kelly who thought of sending her to Mount Holyoke, her own alma mater. Miss Kelly taught her to scour the Irish from her speech and warned her that she’d have to hide her faith at the College. She didn’t know that what Agnes really worshipped was the earthly body, its strung tendons and ligaments, its stony structures. “It will be worth it, Agnes dear, I promise you,” she said, clasping Agnes’s broad hand with her tiny fingers. “It is the best education you could receive. It will do everything for you.”

That her sister Adelaide fell pregnant while working as a housemaid for the Allens in the fall of Agnes’s freshman year and tried to hang herself from the coat hook in their apartment after Mrs. Allen threw her out. When Nora found her she was half-strangled, her heart hardly beating. She lost the baby—poor lamb, said all Nora’s friends, though they were grateful, too. Nora wouldn’t have to choose whether to feed herself or her grandchild, whether or not to abandon the little thing to Saint Mary’s Asylum, which was as good as killing it with her own hands. But Adelaide was, as a result, not quite herself. She could no longer manage anything more complicated than piecework done at their kitchen table; she limped, she forgot how to read. Miss Kelly no longer talked of recommending Adelaide for admission to Mount Holyoke as she had Agnes. So Agnes resolved to do everything for Adelaide herself, if the College could not.

That Nora still worked in the same factory to support herself and Adelaide, though she was forty-six and not hearty and surrounded by girls a third her age doing the same work faster and better.

That Agnes rarely had money to send home and prided herself on never asking for any.

That she worked tirelessly on her drawings not only because she sought perfection for its own sake but because she thought she might be able to work as a medical draughtsman if she could train her hand to be precise enough. Already, the other girls paid her to correct their lab sketches. Her dream was to be a surgeon; she would apply to medical school, and she thought she might even earn a spot. But she had learned to be practical; she had learned always to have two routes of escape.

That she had only been kissed once, by a boy from her school who trapped her in an alley when she was walking home late from Miss Kelly’s and pressed her into the wall and put his dirty hand up her skirt and thrust his dirty fingers into her as if she were a glove. As if she were water, all give and no resistance. As if she were nothing. His mouth tasted of blood and rot. She cut the back of her head on the brick getting away from him—but she cut his cheek with her knife.

That she was still prepared to marry, if she had to, to provide for her mother and Adelaide.

But that she was determined it would not be necessary.

BERTHA KNEW ALL THESE things. But Bertha was not at the College—not anymore.

3

Henry Hammond met Deputy Sheriff F. W. Brockway of the Holyoke police at the Holyoke train station and had his hand shaken energetically. Brockway was young—perhaps forty, scrawny, the sort of fellow who gestured a great deal as he spoke. He was electric with the tension of the search.

Hammond had not known if the local police would welcome his presence, given that he was not a member of the family, but Brockway seemed relieved to deal with him rather than the distraught sister or aged father. “Not what you want to discuss with the family, the sort of trials that might lead a respectable girl to commit a desperate act,” Brockway said as they hurried to the police cart, and Hammond suppressed a flicker of rage.

They rolled through browning fields as Brockway blathered about how they’d found the cannon, which had been sheltering in the barn of a reservist soldier tasked with maintaining it. They were going to meet his convoy of men and artillery and horses at the Connecticut River near Smith’s Ferry, where a brook entered the river and pooled under a small bridge. It was Brockway’s opinion that if Bertha Mellish had gone into the water, whether willingly or not, she was most likely to have done so near this bridge and this pool. If her body was trapped in the pool’s silty hollow or bogged down somewhere nearby in the curls of the river’s course, the cannonball’s force might dislodge it.

“Yes, of course,” Hammond said, only half listening. He was certain Bertha had not gone into any water, in this river or elsewhere, but it was clear that the police meant to focus their attention on the Connecticut until they were satisfied of that fact as well. “Are there other leads in the case?”

“A man came to the station right after we put the word out.” Brockway flicked the reins once more against the backs of the two cart horses. “Said he saw her on the road to Mount Holyoke the day she disappeared. My men found some boot prints going from the road to the riverbank. No tracks back. Little feet, like a child’s, almost.”

Her sweet small feet. Hammond felt a frisson of dread and suppressed that, too. “How do you know the prints weren’t old?”

Brockway shrugged. “Difficult to tell with the freeze and thaw. It’s been bright this month. Unusual.”

As they arrived at the river Hammond took a moment to set himself right—smoothing his hair under his hat, polishing his glasses. “You must tell me how I can help,” he said to the deputy sheriff as they climbed down from the cart. Brockway might’ve been callow but he was in charge of this search, and Hammond had no standing to question the police’s methods. He was only John Mellish’s representative, as far as they knew.

Brockway gave him an unseemly grin. He was too young to have been in the War, so of course he found the cannon-firing exciting. “Just stand back, Doctor.”

The gun was manned by an elderly ex-sergeant and four old cannoneers, one still a coal deliveryman, one a retired fireman, one a druggist, and one too shambling from years of drink to show any evidence of his profession. Hammond spoke with them all as they readied themselves. There was comfort in talking with fellow veterans, and he had the greatest respect for artillerymen; in battle, they might have been based behind the lines, but their work made them targets for every galloping bravo on the field. The exsergeant, he discovered, had been an insurance man. Hammond watched him survey his comrades and linger on the last man with a regard that suggested a blunt professional pity toward someone he would not, under any inducement, have sold a life policy.

“You knew the girl,” the ex-sergeant said to Hammond as they watched two of the other men worm out the bore and swab it, set the range, and aim.

“Yes,” he said, suddenly stricken, “yes,” and stepped back to let them fire.

The ex-sergeant pulled the lanyard and sent the round crashing into the underbrush on the opposite side of the river. It wasn’t just a boom; the gun had a shrill top note, a ripping shriek and whistle, and a cavernous depth to its report that settled in the men’s bellies. They’d grown used to it during the war and they did not flinch. But they sympathized with the shying horses and the terrified crows scattering from the woods on the near riverbank, and Hammond, standing with the deputy sheriff’s searchers, wondered how many old men in the valley had just lifted their heads from their work and looked toward a window or the horizon, seeking out the danger that matched that sound.

He couldn’t escape the feeling that the men had just sounded Bertha’s death knell. A tremendous echoing call along the floor of the valley, bigger in the ears than any church bell. Everyone at the College must have heard it. Florence Mellish must have heard it.

The sergeant watched the policemen pick their way along the brown banks of the river and peer into its murk. The cannoneers weren’t needed any longer—one shot would have to be sufficient, as there were farms nearby and more blasts might upset the livestock—but they stood around the cannon for a while, talking to each other and the horses, until it was clear that no bodies were going to rise up from the river’s depths. Then they packed up all the cannon’s gear, the sight and the swab and the wire, the lanyard and the firing table, and turned their backs on the river.

Nearby, the police dragged chains up Batchelder Brook for several hours before being thwarted by ice and came up with nothing useful—some trash and a mess of branches and leaves, a deer’s half-consumed carcass. Later they dragged the river with grappling hooks, too, and stretched a net across it miles downstream. They drew down the lakes on campus and found a number of glinting hairpins, a smashed hat that might once have been blue, a belt buckle, a cluster of old bricks, half a teacup, the nickel-plated clasp from a handbag, and the sodden remains of several textbooks still bound together with a leather strap, probably thrown in jubilantly by a Holyoke girl at the end of term.

There was no hint of Bertha among the wet weeds.

4

A brisk wind blew the street in front of Mary Lyon Hall clean of leaves and made the newly planted trees near the hall quiver skeletally under its force. Florence had been standing on this corner for half an hour waiting for Dr. Hammond with her gloves off again, her raw hands shoved into her joined coat sleeves as if in a muff. Despite all the changes to the campus, memories besieged her as she studied the place. On that soft lawn she had met an acquaintance for a game of kitten ball; beneath that oak tree, in its sapling days, she’d swooned over Greek poetry; there, near the wrought iron fence that separated the campus from town, she had chatted idly with other girls about whether it was more enviable to marry a man with a missionary calling or one dedicated to his own community, as if either pairing were possible for her.

It was Saturday afternoon. Soon she would have to return to work, whether they had found Bertha or not. A substitute would cover her classes this week, but the principal’s indulgence was limited even in cases of emergency. Florence had left an unread pile of essays on the desk in her bedroom at home, with a note imploring her mother, Sarah, not to touch them.

If Florence was lucky, their neighbor Mrs. Christopher, whom she’d begged to stay with her mother, would tire Sarah out with talk of fine-work and thread and the inconsequential town gossip they both delighted in. If Florence proved unlucky, her mother might not be satisfied with dull Mrs. Christopher, might go wandering about the house, since the Reverend was away, and injure herself. She had been unsteady on her feet for decades, but the last year had been the worst: six spills, with the bruises from the last still pale iodine yellow on her papery skin. Sometimes Sarah seemed to fall on purpose, to force the Reverend’s attention or Florence’s. Sometimes she seemed to have no more intention than a moth fluttering about in a bare closet.

They had not informed Sarah of Bertha’s disappearance yet. “When we return,” her father had said, “if we must, we’ll tell her then,” and Florence found herself in rare agreement with him.

Students passed while Florence waited, twenty or thirty of them. Those in groups fell silent as they approached her, and all the girls bent their heads to avoid meeting her eyes. They were so lovely, so healthy and fine in their variety that her heart stung to see them. She studied a pair of elegant cheekbones; a broad hand clamped around the spine of a textbook; a tendril of hair caught in a girl’s blinking eyelashes; a nervous little mouth not yet thinned, as it would thin, with age.

In a fortnight, Florence would turn forty-one. She’d be back in Killingly, back at the school with her students, back in the dull dreadful house in the evenings with her mother and father. These girls would still be here, still growing, like vines tacked to a trellis. And where would Bertha be?

There had been no news from her father, nothing about the girl in the city who called herself Bertha, though he ought to have arrived in the city hours ago. She told herself that he must not have seen the girl yet. The police were busy, and he would want to be sure before he sent word.

The wheels of Dr. Hammond’s carriage rattled in the dust as it drew near. He must have seen her standing there, but the carriage stopped a good twenty feet away. She tried to control the icy surge of disgust she felt at the sight of his genial face and neat whiskers and at the alacrity with which he swung down from the carriage. She had expected a somber expression in these circumstances, but instead he looked almost cheerily determined, as if his presence would be all that was required to sort out the horrible mess of Bertha’s absence. If only God had not taken Justin Hammond, this Dr. Hammond’s father, in ’73—if he had lived just four years longer—she would not find herself beholden to this particular condescending man, who’d taken such a possessive interest in Bertha and kept himself so close to the family that Florence could not see how he would ever be extricated from their lives.

“Miss Mellish,” Dr. Hammond said as he approached. Cordial, as if they were meeting at a dinner party and about to have a pleasant chat. “I am so sorry. I’ve come as quickly as I could. Your father is in Boston, I understand? At the hospital?”

“Dr. Hammond,” she answered, shifting back from the billow of his cologne. “There was a girl admitted as Bertha Miller, so the Boston police notified the College. But he has not sent any word since he arrived this morning. I doubt that it is her.”

He grasped her forearm and she jerked unhappily. She always aimed to avoid his touch. “You mustn’t worry. I’m here now to help you find her. I’ve just come from Brockway, the deputy sheriff. They’ve been searching the river. No sign, of course.”

She imagined her arm heating until it scorched his palm through the sleeve of her coat. Still he did not release her, and she did not wrest her arm from his grasp, because he was right. His presence mattered here as it mattered everywhere. He was a respected widower in his mid-fifties, and she was the spinster sister—and she would do anything for Bertha, even let this man think himself her keeper and look at her with his pitying eyes.

“We should talk to the girls,” she said when he finally did let go. “There’s one, Agnes, who seems to be closest with her. And a girl named Mabel, Mrs. Mead says, that Bertha asked to go walking on Thursday. What did my father tell you?”

“Very little. His letter was . . .”

She waited.

“Confusing,” Dr. Hammond said, after a moment. “It concerned me. As his physician. Are you sure it was wise for him to go to Boston alone?”

A disbelieving laugh caught in her throat. “Hardly. But it was not my choice. He would not let me go with him.”

“I see.” Of course he didn’t see. He thought her too harsh and unloving to her father. He was hypothesizing, as Bertha would’ve said haughtily, based on incomplete information. “Brockway told me the police found footprints at the river, but the cannon—There was nothing.”

He looked toward the river—almost involuntarily, it seemed—as he spoke. Florence said nothing. She had heard the cannon fire. She knew what it was meant to do. But what good could come of thinking of Bertha’s body floating up from the river’s depths?

Hammond turned back. “Why don’t you tell me what you know, Miss Mellish.”

“She’s been gone since Thursday afternoon, but nobody knew it until Friday, yesterday, first thing. There were men out walking the woods yesterday. There are people saying they saw her on the roads by the river.” He was frowning. She had to agree with his dismissal; people wanted to see Bertha, to be the ones to find the missing girl, so they thought they had. “And then there’s the rumor of the girl at the hospital. But—”

“Yes.” Dr. Hammond cut her off, rather gently. “You think it’s not her.”

“No.” As she said it she knew it was true. “It’s not.”

Dr. Hammond looked up at Mary Lyon Hall. A woman was waving to them from the arched doors below the clock tower. “Come. We’ll speak to the girls. Perhaps you’re wrong.”

5

Nobody else had wanted Agnes’s room on the third floor of Porter Hall. One window faced the squat granite pillar at the center of campus that marked Mary Lyon’s grave, enclosed by sharp iron finials within a dark grove of trees Agnes could not name. Of course, all the rooms at the front of Porter faced the Founder’s grave. The problem was Agnes’s other window, which looked across the divide between wings of the building, a shaft just a few feet wide meant to let in light. The other girls whined about staring at a brick wall or having to keep their shades down for privacy. But Agnes liked the confinement, familiar from tenement life. She was not much given to fantasy, but she imagined herself at times as a creature in the stories Adelaide loved, sheltered in this clean new room as if in a mountain lair.

Yet now they’d come to beard Agnes in her den: Florence Mellish, Bertha’s older sister, and an older man whom she clearly did not like much. Florence offered Agnes her hand to shake. Bertha’s sister had coarse skin and calloused fingers, and she looked older than Agnes had expected but strong, a workhorse of a woman. Agnes saw Bertha in the soft under-curve of her jaw and the pert angle of her nose. Otherwise, they barely resembled each other. Florence’s bones were broad and heavy, and Bertha’s had been so finely made that she seemed bird-light and fluttery until you saw the metal in her eyes and the tight crank of her determined smile.

Florence kept the gentleman accompanying her at heel. At the sight of him Agnes was struck by an unfamiliar sensation of queasy timidity. This was the fearsome Dr. Hammond, who had delivered Bertha and treated her for years for what he called “nervous complaints,” what Agnes would have described as stubbornness and singularity. She’d never seen him in person before, but she knew a great deal about him from Bertha, who’d shown her all the letters he’d sent, letters now stored in her own trunk along with Bertha’s other correspondence. The letters had begun by offering tribute to Bertha’s many virtues, but since the beginning of the year they had swerved decidedly toward chivalric romance. Bertha had told Agnes about Hammond’s letters because she knew Agnes would never push her to accept or deny him. She’d known that Agnes was perfectly indifferent to the men who pursued her, as long as they did not actually threaten to take her away from her studies.

But Agnes could not afford to be indifferent to Hammond now.

“This is Dr. Hammond, our family physician,” said Florence, and Agnes extended her hand to the man as if she knew nothing of him. “Dr. Hammond, Agnes Sullivan, Bertha’s dearest friend at the College.”

Agnes supposed that Hammond was always dapper and finelooking, but today he seemed to have dressed with special care in a pin-striped suit and waistcoat. His collar stood up boldly, his watch chain gleamed, his gray-brown mustache had been trimmed with mathematical precision, his salmon-colored pocket square rose to a tender little point. A handsome enough man, for his age, but soft-looking somehow. He was tucking a pair of spectacles away inside his coat as he reached out to shake her hand. He even smelled expensive, like lemon and talcum and spice. Next to his polish, Florence’s simple crown of braids, brown dress, and checked shawl looked shabby rather than neat.

“Dr. Hammond is sure that Bertha must still live,” said Florence.

Agnes looked at him with sharper eyes. “I should hope so,” she said and wondered at his composure. He didn’t seem concerned in the least that she might tell Florence she had seen him on campus before. Did he think that Bertha had kept his letters secret? Or that the Reverend Mellish would endorse his suit?

“The police are doing all they can,” he said, looking upon Agnes gravely, “and if their efforts prove insufficient there are other means of investigation. You must not lose hope, Miss Sullivan. We will seek out Miss Mellish and return her to her loved ones.”

Hammond was a speechmaker by nature, Agnes could tell, and considered himself a leader of men. He edged past Florence’s elbow, deeper into Agnes’s room. She had no photographstudded fishnet dangling from the walls, no gleaming Gibson Girls smirking down from posters. Only books, her paltry personal effects spread on the dresser’s top, the cross-stitched Protestant hymns and the plain cross left by the room’s previous tenant, and the sole indulgence of her true interests—a few lists of Latin names tacked to the plaster as aide-mémoire. Agnes found herself exchanging a speaking glance with Florence Mellish. She felt reassured by Florence’s obvious distaste for the man. Bertha had told Agnes little about her sister, in that protective way she had, afraid of saying too much about the things she really loved. It was one of the first things Agnes had recognized in her when they were freshmen. She knew that Florence was a teacher; honorable work, especially for a woman who’d been too unwell to finish her own education.

“Did she appear upset to you? Before?” Florence asked. “About her studies, perhaps, or some other affair? Has she told you of anything that’s been worrying her?”

“No,” said Agnes. “She’s been anxious about the debate, but she was excited, not upset.” She had told herself to answer only what she was asked when they came to speak with her, but Florence’s face was so awfully open, so eager for more knowledge of Bertha that Agnes did not stop. Nor did she lie, when she could avoid it. She told them which recitations Bertha had liked best, how her preparations for the debate on vivisection had been proceeding, what she had eaten and what she had only picked at, how often she retired to her single room and put up the Engaged sign to keep the other girls out. Agnes had her own Engaged sign. It was hanging from her room’s doorknob at that moment, and even now, even after Bertha’s disappearance, none of the Porter girls were likely to brave Agnes’s room. They thought all she did inside was study and pray.

“There were no disputes with any of the other girls? Perhaps over a young man.” Hammond turned back to the two of them. Agnes kept her face blank.

Florence’s eyelids tightened. “She’s said nothing to me about—”

“You are not her bosom friend any longer, Miss Mellish,” Hammond said in a poisonously gentle tone, and Agnes saw a shudder go through Florence’s body. Bertha’s sister was twisting her hands together in front of her stomach: an unconscious expression of anxiety, or a desire to throttle the doctor. Or perhaps both.

“Nothing of that sort,” Agnes said. “Bertha is too busy with her studies to bother with the other girls much. And certainly she has no interest in their parties or their young men. She doesn’t loll around cooking fudge in a dish when she could be doing real chemistry.”

“What does she do on a Friday evening, then?” Hammond picked up one of Agnes’s books from the dresser top and thumbed through it, and Agnes felt the same shudder, as if his hands were on her own skin. She thought of the last happy Friday evening she’d spent with Bertha—side by side in the library, heads bent at the same angle, pens scratching in rhythm. Bertha had drilled her on anatomical terms and read Greek lyrics aloud as she translated them, bright-eyed as Athena, strange vowels in the wine-darkness of her mouth.

She said shortly, “We study together. We always study together.”

“Do you,” said Florence in a softer voice. “I’m glad to know that. She is always cheerful in her letters, but it is hard with Bertha to know—if she’s happy. Truly happy.”

Agnes didn’t know what to say. It had been hard to know if Bertha was happy, it was true. She watched as Hammond put the book down atop the dresser a good foot away from where it had been before.

After a moment Florence cleared her throat. “Do you think—could she have had some reason to avoid the Founder’s Day ceremony?”

“I don’t believe so. It’s tiresome but not very long. I left early myself. Nobody minds, if you have to. But Bertha didn’t—” Agnes drew a deep breath, thinking of her lungs filling, her heart slowing. “Bertha didn’t plan to go in the first place. She was working on her arguments for the debate, doing more research. She said there was always more to do if she wanted to be the best prepared.”

That made Florence exhale a little laugh. “Our Bertha,” she said, looking into Agnes’s eyes so that Hammond was neatly excluded.

Yes, Agnes thought. Our Bertha.

“The girls say that no one saw her at the ceremony at all, but Mrs. Mead tells us that one girl did claim to have seen her elsewhere on the campus, walking to the west. Carrying books—She used to do that as a child, you know,” Florence said, clearly arrested by memory. Her hands fell to her sides and her eyes glazed. “Go for a long walk with a book and get so lost in it I would have to go out in search of her for supper. We joked about calling out the sheriff to look for her.” She breathed out heavily. “My God.”

Dr. Hammond crowded close to put a meaty hand on Florence’s shoulder. “Take heart,” he murmured, then looked to Agnes. “Miss Sullivan, you never saw anything or heard Miss Mellish say anything that seemed extraordinary, in the last few days?”

“Bertha is always extraordinary,” said Agnes. Florence shook off Hammond’s touch by reaching out to grasp Agnes’s fingers in what seemed to be a gesture of thanks for that statement. Agnes did not like to be touched, either, but forced herself to remain still and to ignore Hammond’s gaze upon the two of them. She recited the tendons of the hand to quiet her mind—first dorsal interosseous, abductor pollicis, extensor pollicis longus, extensor digitorum communis—and soon enough Florence pulled her hand back. Often when Agnes recited silently to herself that way people thought she was praying. She could not tell what Florence thought. Reading others’ emotions was always difficult, and on Florence’s face, with its echoes of Bertha, all Agnes could see was misery.

Guilt stabbed at her viscera. They were both staring at her now, Hammond hovering behind Florence’s left shoulder like a haunt. Agnes said, “She might have spoken to Mabel about these matters.”

Florence’s eyes narrowed. “Mabel?”

“Mabel Cunningham, I mean, Bertha’s senior—”

“Her senior?” Hammond interrupted.

“There’s a system,” Florence said impatiently. “For matching up the upperclassmen with girls the year below, so everybody has a particular friend to look up to.”

Agnes nodded. “Bertha asked Mabel to go out walking—that day. Thursday. Before she disappeared. But beyond that—there is nothing else. I am sorry.”

“She sent us a letter on Sunday,” Florence said. “Full of news about the debate and her other projects. It was all enthusiasm. Nothing that showed any distress. It’s in the papers this morning, that she was troubled. But you know her, Agnes, you know she is not. Not like that.”

Not like that.

“Bertha is not troubled. She is the smartest girl I know,” said Agnes. “The most loyal, and the best.”

She saw knowledge bloom in Florence’s face, then surprise—that Agnes loved Bertha. That anyone loved Bertha. This made Agnes fume in silence. So Bertha was a quiet and peculiar girl. It was what all the girls were babbling to one another, what they would write to their shocked mothers and tell the newspapermen. Queer and strange, not known to make girl friends easily, never once accompanied to a party by a young man, not even a classmate from Danielson High School. All of that was true, but Florence must know all the other truths about Bertha. The glories of her.

Agnes called Bertha to mind. She had been resisting this because thinking of Bertha now caused her tremendous pain, though not like the pain of a bruise or a fracture. Like a deep incision. She’d cut herself twice with her scalpel in freshman year so that she would know what it felt like: carved two cold-burning slices into the soft skin over her inner biceps. Bertha had bandaged them, her little fingers nimbler and her eyes knowing but kind.

Bertha’s very presence was a salve for the foolishness of the all-around girls, their pranks and songs and tawdry camaraderie. She offered Agnes the inexpressible relief of being understood. Bertha would declare herself an agnostic to any girl unfortunate enough to ask why she never went to the Congregational church, next to the College to hear the new minister sermonize, but she never said a word to anyone else about Agnes’s Catholic childhood. She knew that history alone put Agnes at risk of expulsion from Mount Holyoke, only three years into its new life as a college rather than a seminary school and still dedicated to educating its girls to resist the blandishments of Catholic Europe. Bertha was accomplice and protector.

Florence was giving her a measuring stare, and Agnes looked down in distress. She was used to turning that look on others, not to suffering it. She could see now why it made the other girls flinch.

They stood in silence. Agnes kept studying the plain floorboards. Hammond, his back to the two of them, gazed out her window toward Mary Lyon’s grave. Florence drew in a slow breath.

Agnes wanted them to leave; she wanted Florence to take her terrible sadness away.

She had her work to focus on, her French and Latin and German to study and the last round of research for her zoology dissection project to begin. Before Florence and Hammond arrived she had been drilling conjugations. After they left she would return to it for thirty minutes, and then, after a five-minute break, would read one of the short pamphlets she had found in the library on the cat fancy. She believed in honoring the creatures she had to sacrifice for her own education by learning about them—learning everything she possibly could.

Work was all Agnes could do now. Work was what she had promised Bertha she would do.

“Please,” she said to Florence and Hammond, her voice raw. “I am sorry. I have so much to do before Bible study.”

6

Mabel Cunningham was lovely when she cried and she knew it. There was something theatrical about her expressions and about the way she twisted her beautifully finished lawn handkerchief between delicate fingers. Florence was sure the girl had embroidered the cloth herself and equally sure that she would have blushed if asked to confirm it. The blush was as intrinsic to her nature as the talent, and both were meant to captivate admirers other than Florence.

“I am sorry,” Mabel said, touching the tips of those elegant fingers to the shell-pink coverlet beside her, as if to steady herself. She’d led them from the drawing room back to this haven of femininity on the third floor and had sunk down upon the edge of her bed at Dr. Hammond’s first question. “It’s just that we are all so worried about her.”

Florence studied Mabel as she wiped at her eyes, then looked to Dr. Hammond, who was frowning at the girl in a way that would have chilled a less ebullient spirit. But even in anguish, auburn-haired Mabel glowed demurely. She was a different model from the girls who had reigned during Florence’s year at the College, but no less winning. Florence had envied their easy success, their freedom. But she had no patience for the girl’s performance today. She wanted to dig her fingers into the puffs of Mabel’s sleeves and shake her.

“I feel terrible about having refused her,” Mabel said without prompting. She reached for one of the jade-flowered pillows propped at the head of the bed and pressed it against her middle. Her fingers twined in its ivory ruffles. The whole room had a feeling of abundance. The bookshelves held as many framed photographs as they did books, and the bedside lamp and mirror were garlanded with ribbons and other mementos. The stoppered glass perfume bottles on the dresser whispered of lilac, violet, musk. It was everything Bertha’s room was not.

Dr. Hammond nodded at Mabel, curtly, as if to say: You should.

“I was studying—I had a Latin exam the next day, and of course I had to attend Founder’s Day. I thought of going with her just for a little while, but it was clear that she wanted a long walk, and I just hadn’t the time. And she was quite nice about it really—or nice for Bertha. I mean, not that she wasn’t usually nice, just that she could be a bit short sometimes, if you understand?” The girl gave a graceful shrug, sounding both fond and critical. “When she was really involved with her schoolwork. But she always did treat me awfully well, and she never expected too much of me.”

“Expected too much?” Dr. Hammond narrowed his eyes. “What do you mean by that, Miss Cunningham?”

“I’m her senior,” Mabel said. “A sort of—elder sister.” She darted an opaque look at Florence. “Everybody said—Well, there were some girls who didn’t want to take Bertha on because she was so quiet. You know the type, maybe. The all-arounders who think a week is incomplete without a fête of some sort, a dance with a young man or at least a gathering in someone’s room with a really fine spread to take everybody’s mind off studying. That kind of girl. They weren’t much for Bertha, and I can’t say she was much for them, either. But I liked her.” She caught herself. “I like her.”

“What did she expect of you, then?” Florence asked.

Mabel’s brow tensed. “Why, just an ear, on occasion, I suppose. More often than not we talked about the debates. We’re to argue the affirmative together, and she’s really very promising—everybody says so. Classics students are such good rhetoricians. I don’t know what we’ll do without her. I suppose it may be put off—”

Dr. Hammond interrupted her. “But she has not told you anything private, anything you think could help the police as they search for her?”

Mabel went wide-eyed. “Oh, no, of course not. I’d have said at once if I thought there was anything. It’s just that—I haven’t seen her as much this year. I saw her more before I was her senior, honestly, because of debate. She’s always so busy preparing this project or that, or writing up her little lectures. And of course my schoolwork keeps me busy, too, and so does basketball. And William,” she said, with a flare of dimples, “my fiancé. He’s finishing his medical degree at Dartmouth this year.” Florence closed her eyes for just a moment. Against her eyelids came flashes of the dreams she’d silently cherished: Bertha wed to a man worthy of her. Bertha in white lace, embracing Florence in front of the congregation. “But—I’m sorry, you must forgive me; it’s like a disorder, I simply can’t stop talking about him. What I meant to say was that I haven’t seen Bertha as much since the fire.”

“The fire,” said Hammond, looking bewildered by the rush of Mabel’s speech.

“Last year the seminary building burnt—you must remember. The fire was enormous, everything was destroyed, and nearly all of us lost our belongings. They put us up in town, mostly. I lived in the Boyds’ hotel with a few other girls from the class of ’98. And Bertha and Agnes, they lived in Mrs. Drew’s house, out on the ferry road. Everybody thought it rather fitting,” she added shyly, “the two odd birds nesting together.”

Florence thought she discerned the slightest sidelong look at the end of that sentence, as if Mabel were evaluating her for inclusion in the category of “odd bird.” It would be impossible to control the rumors of madness in the family, that was certain—how stupid she’d been to hope that the girls would emulate Mrs. Mead’s restraint. Behind his polite expression she could see that Hammond was furious. Her father would be, too.

Mabel continued, “Even though we all live in Porter now, I only really see them at meals and classes. So even if Bertha had anything secret to share, which I rather doubt, I don’t know that she would have thought to share it with me.”

“Well, regardless, if you recall anything that seems relevant—even the smallest item of information may be crucial—I hope you will tell Mrs. Mead directly. Or tell me.” Dr. Hammond passed her one of his cards and stood. “I will be staying in town until we know more, to assist the family.”

Mabel turned the force of her blue eyes squarely on Florence. “Miss Mellish,” she said warmly, “I will be thinking of you.”

“My thanks,” Florence managed to say. How strange it was to imagine Bertha exchanging a single sentence with this glossy paragon of a girl.

Outside Mabel’s room, Florence stopped and put one hand to her mouth. She closed her eyes. A few rooms down the hall a girl chattered about a biology assignment. Farther away, another girl practiced scales. Her voice wobbled up and down like a cat’s cry.

Hammond fussed with one of his cuffs, then looked at the wall as if its paper fascinated him. Its pattern contained the same colors as Mabel’s room, Florence noticed, the pale pink of the ground, the soft green figures. Probably he was trying to decide what condescending thing would be best to say to her. How precisely to encourage her not to lose heart or to remain strong or to think of her sister. As if she had ever stopped thinking of Bertha—or ever would.

AS FLORENCE AND HAMMOND left her room, Mabel settled uneasily back against her pillows, sorting through her recent memories of Bertha. She hadn’t exactly lied—she did like the girl, admired her gift for argumentation, her tenacious mind. But Bertha also unsettled her. That little smirk on her clever lips that said without speaking: I don’t need you and I don’t care a whit what you think of me.