Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Ozymandias Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

While France was deluged with the blood of a civil war, young Henry was busily pursuing his studies in college. He could have had but little affection for his father, for the stern soldier had passed most of his days in the tented field, and his son had hardly known him. From his mother he had long been separated; but he cherished her memory with affectionate regard, and his predilections strongly inclined him toward the faith which he knew that she had so warmly espoused. It was, however, in its political aspects that Henry mainly contemplated the question. He regarded the two sects merely as two political parties struggling for power. For some time he did not venture to commit himself openly, but, availing himself of the privilege of his youth, carefully studied the principles and the prospects of the contending factions, patiently waiting for the time to come in which he should introduce his strong arm into the conflict...

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 302

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

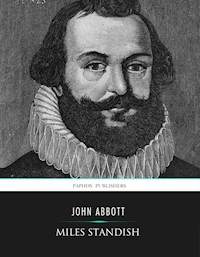

King Henry IV

John Abbott

OZYMANDIAS PRESS

Thank you for reading. If you enjoy this book, please leave a review or connect with the author.

All rights reserved. Aside from brief quotations for media coverage and reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced or distributed in any form without the author’s permission. Thank you for supporting authors and a diverse, creative culture by purchasing this book and complying with copyright laws.

Copyright © 2016 by John Abbott

Interior design by Pronoun

Distribution by Pronoun

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Childhood and Youth.

Civil War.

The Marriage.

Preparations for Massacre.

Massacre of St. Bartholomew.

The Houses of Valois, of Guise, and of Bourbon.

The Death of Charles IX. and the Accession of Henry III.

The League.

The Assassination of the Duke of Guise and of Henry III.

War and Woe.

The Conversion of the King.

Reign and Death of Henry IV.

Childhood and Youth.

1475-1564

About four hundred years ago there was a small kingdom, spreading over the cliffs and ravines of the eastern extremity of the Pyrenees, called Navarre. Its population, of about five hundred thousand, consisted of a very simple, frugal, and industrious people. Those who lived upon the shore washed by the stormy waves of the Bay of Biscay gratified their love of excitement and of adventure by braving the perils of the sea. Those who lived in the solitude of the interior, on the sunny slopes of the mountains, or by the streams which meandered through the verdant valleys, fed their flocks, and harvested their grain, and pressed rich wine from the grapes of their vineyards, in the enjoyment of the most pleasant duties of rural life. Proud of their independence, they were ever ready to grasp arms to repel foreign aggression. The throne of this kingdom was, at the time of which we speak, occupied by Catharine de Foix. She was a widow, and all her hopes and affections were centred in her son Henry, an ardent and impetuous boy six or seven years of age, who was to receive the crown when it should fall from her brow, and transmit to posterity their ancestral honors.

Ferdinand of Aragon had just married Isabella of Castile, and had thus united those two populous and wealthy kingdoms; and now, in the arrogance of power, seized with the pride of annexation, he began to look with a wistful eye upon the picturesque kingdom of Navarre. Its comparative feebleness, under the reign of a bereaved woman weary of the world, invited to the enterprise. Should he grasp at the whole territory of the little realm, France might interpose her powerful remonstrance. Should he take but the half which was spread out upon the southern declivity of the Pyrenees, it would be virtually saying to the French monarch, “The rest I courteously leave for you.” The armies of Spain were soon sweeping resistlessly through these sunny valleys, and one half of her empire was ruthlessly torn from the Queen of Navarre, and transferred to the dominion of imperious Castile and Aragon.

Catharine retired with her child to the colder and more uncongenial regions of the northern declivity of the mountains. Her bosom glowed with mortification and rage in view of her hopeless defeat. As she sat down gloomily in the small portion which remained to her of her dismembered empire, she endeavored to foster in the heart of her son the spirit of revenge, and to inspire him with the resolution to regain those lost leagues of territory which had been wrested from the inheritance of his fathers. Henry imbibed his mother’s spirit, and chafed and fretted under wrongs for which he could obtain no redress. Ferdinand and Isabella could not be annoyed even by any force which feeble Navarre could raise. Queen Catharine, however, brooded deeply over her wrongs, and laid plans for retributions of revenge, the execution of which she knew must be deferred till long after her body should have mouldered to dust in the grave. She courted the most intimate alliance with Francis I., King of France. She contemplated the merging of her own little kingdom into that powerful monarchy, that the infant Navarre, having grown into the giant France, might crush the Spanish tyrants into humiliation. Nerved by this determined spirit of revenge, and inspired by a mother’s ambition, she intrigued to wed her son to the heiress of the French throne, that even in the world of spirits she might be cheered by seeing Henry heading the armies of France, the terrible avenger of her wrongs. These hopes invigorated her until the fitful dream of her joyless life was terminated, and her restless spirit sank into the repose of the grave. She lived, however, to see her plans apparently in progress toward their most successful fulfillment.

Henry, her son, was married to Margaret, the favorite sister of the King of France. Their nuptials were blessed with but one child, Jeanne d’Albret. This child, in whose destiny such ambitious hopes were centred, bloomed into most marvelous beauty, and became also as conspicuous for her mental endowments as for her personal charms. She had hardly emerged from the period of childhood when she was married to Antony of Bourbon, a near relative of the royal family of France. Immediately after her marriage she left Navarre with her husband, to take up her residence in the French metropolis.

One hope still lived, with undying vigor, in the bosom of Henry. It was the hope, the intense passion, with which his departed mother had inspired him, that a grandson would arise from this union, who would, with the spirit of Hannibal, avenge the family wrongs upon Spain. Twice Henry took a grandson into his arms with the feeling that the great desire of his life was about to be realized; and twice, with almost a broken heart, he saw these hopes blighted as he committed the little ones to the grave.

Summers and winters had now lingered wearily away, and Henry had become an old man. Disappointment and care had worn down his frame. World-weary and joyless, he still clung to hope. The tidings that Jeanne was again to become a mother rekindled the lustre of his fading eye. The aged king sent importunately for his daughter to return without delay to the paternal castle, that the child might be born in the kingdom of Navarre, whose wrongs it was to be his peculiar destiny to avenge. It was mid-winter. The journey was long and the roads rough. But the dutiful and energetic Jeanne promptly obeyed the wishes of her father, and hastened to his court.

Henry could hardly restrain his impatience as he waited, week after week, for the advent of the long-looked-for avenger. With the characteristic superstition of the times, he constrained his daughter to promise that, at the period of birth, during the most painful moments of her trial, she would sing a mirthful and triumphant song, that her child might possess a sanguine, joyous, and energetic spirit.

Henry entertained not a doubt that the child would prove a boy, commissioned by Providence as the avenger of Navarre. The old king received the child, at the moment of its birth, into his own arms, totally regardless of a mother’s rights, and exultingly enveloping it in soft folds, bore it off, as his own property, to his private apartment. He rubbed the lips of the plump little boy with garlic, and then taking a golden goblet of generous wine, the rough and royal nurse forced the beverage he loved so well down the untainted throat of his new-born heir.

“A little good old wine,” said the doting grandfather, “will make the boy vigorous, and brave.”

We may remark, in passing, that it was wine, rich and pure: not that mixture of all abominations, whose only vintage is in cellars, sunless, damp, and fetid, where guilty men fabricate poison for a nation.

This little stranger received the ancestral name of Henry. By his subsequent exploits he filled the world with his renown. He was the first of the Bourbon line who ascended the throne of France, and he swayed the sceptre of energetic rule over that wide-spread realm with a degree of power and grandeur which none of his descendants have ever rivaled. The name of Henry IV. is one of the most illustrious in the annals of France. The story of his struggles for the attainment of the throne of Charlemagne is full of interest. His birth, to which we have just alluded, occurred at Parr, in the kingdom of Navarre, in the year 1553.

His grandfather immediately assumed the direction of every thing relating to the child, apparently without the slightest consciousness that either the father or the mother of Henry had any prior claims. The king possessed, among the wild and romantic fastnesses of the mountains, a strong old castle, as rugged and frowning as the eternal granite upon which its foundations were laid. Gloomy evergreens clung to the hill-sides. A mountain stream, often swollen to an impetuous torrent by the autumnal rains and the spring thaws, swept through the little verdant lawn, which smiled amid the stern sublimities surrounding this venerable and moss-covered fortress. Around the solitary towers the eagles wheeled and screamed in harmony with the gales and storms which often swept through these wild regions. The expanse around was sparsely settled by a few hardy peasants, who, by feeding their herds, and cultivating little patches of soil among the crags, obtained a humble living, and by exercise and the pure mountain air acquired a vigor and an athletic-hardihood of frame which had given them much celebrity.

To the storm-battered castle of Courasse, thus lowering in congenial gloom among these rocks, the old king sent the infant Henry to be nurtured as a peasant-boy, that, by frugal fare and exposure to hardship, he might acquire a peasant’s robust frame. He resolved that no French delicacies should enfeeble the constitution of this noble child. Bareheaded and barefooted, the young prince, as yet hardly emerging from infancy, rolled upon the grass, played with the poultry, and the dogs, and the sturdy young mountaineers, and plunged into the brook or paddled in the pools of water with which the mountain showers often filled the court-yard. His hair was bleached and his cheeks bronzed by the sun and the wind. Few would have imagined that the unattractive child, with his unshorn locks and in his studiously neglected garb, was the descendant of a long line of kings, and was destined to eclipse them all by the grandeur of his name.

As years glided along he advanced to energetic boyhood, the constant companion, and, in all his sports and modes of life, the equal of the peasant-boys by whom he was surrounded. He hardly wore a better dress than they; he was nourished with the same coarse fare. With them he climbed the mountains, and leaped the streams, and swung upon the trees. He struggled with his youthful competitors in all their athletic games, running, wrestling, pitching the quoit, and tossing the bar. This active out-door exercise gave a relish to the coarse food of the peasants, consisting of brown bread, beef, cheese, and garlic. His grandfather had decided that this regimen was essential for the education of a prince who was to humble the proud monarchy of Spain, and regain the territory which had been so unjustly wrested from his ancestors.

When Henry was about six years of age, his grandfather, by gradual decay, sank sorrowingly into his grave. Consequently, his mother, Jeanne d’Albret, ascended the throne of Navarre. Her husband, Antony of Bourbon, was a rough, fearless old soldier, with nothing to distinguish him from the multitude who do but live, fight, and die. Jeanne and her husband were in Paris at the time of the death of her father. They immediately hastened to Bearn, the capital of Navarre, to take possession of the dominions which had thus descended to them. The little Henry was then brought from his wild mountain home to reside with his mother in the royal palace. Though Navarre was but a feeble kingdom, the grandeur of its court was said to have been unsurpassed, at that time, by that of any other in Europe. The intellectual education of Henry had been almost entirely neglected; but the hardihood of his body had given such vigor and energy to his mind, that he was now prepared to distance in intellectual pursuits, with perfect ease, those whose infantile brains had been overtasked with study.

Henry remained in Bearn with his parents two years, and in that time ingrafted many courtly graces upon the free and fetterless carriage he had acquired among the mountains. His mind expanded with remarkable rapidity, and he became one of the most beautiful and engaging of children.

About this time Mary, Queen of Scots, was to be married to the Dauphin Francis, son of the King of France. Their nuptials were to be celebrated with great magnificence. The King and Queen of Navarre returned to the court of France to attend the marriage. They took with them their son. His beauty and vivacity excited much admiration in the French metropolis. One day the young prince, then but six or seven years of age, came running into the room where his father and Henry II. of France were conversing, and, by his artlessness and grace, strongly attracted the attention of the French monarch. The king fondly took the playful child in his arms, and said affectionately,

“Will you be my son?”

“No, sire, no! that is my father,” replied the ardent boy, pointing to the King of Navarre.

“Well, then, will you be my son-in-law?” demanded Henry.

“Oh yes, most willingly,” the prince replied.

Henry II. had a daughter Marguerite, a year or two younger than the Prince of Navarre, and it was immediately resolved between the two parents that the young princes should be considered as betrothed.

Soon after this the King and Queen of Navarre, with their son, returned to the mountainous domain which Jeanne so ardently loved. The queen devoted herself assiduously to the education of the young prince, providing for him the ablest teachers whom that age could afford. A gentleman of very distinguished attainments, named La Gaucherie, undertook the general superintendence of his studies. The young prince was at this time an exceedingly energetic, active, ambitious boy, very inquisitive respecting all matters of information, and passionately fond of study.

Dr. Johnson, with his rough and impetuous severity, has said,

“It is impossible to get Latin into a boy unless you flog it into him.”

The experience of La Gaucherie, however, did not confirm this sentiment. Henry always went with alacrity to his Latin and his Greek. His judicious teacher did not disgust his mind with long and laborious rules, but introduced him at once to words and phrases, while gradually he developed the grammatical structure of the language. The vigorous mind of Henry, grasping eagerly at intellectual culture, made rapid progress, and he was soon able to read and write both Latin and Greek with fluency, and ever retained the power of quoting, with great facility and appositeness, from the classical writers of Athens and of Rome. Even in these early days he seized upon the Greek phrase “ἡ νικãν ἡἁποθαεἱν,” to conquer or to die, and adopted it for his motto.

La Gaucherie was warmly attached to the principles of the Protestant faith. He made a companion of his noble pupil, and taught him by conversation in pleasant walks and rides as well as by books. It was his practice to have him commit to memory any fine passage in prose or verse which inculcated generous and lofty ideas. The mind of Henry thus became filled with beautiful images and noble sentiments from the classic writers of France. These gems of literature exerted a powerful influence in moulding his character, and he was fond of quoting them as the guide of his life. Such passages as the following were frequently on the lips of the young prince:

“Over their subjects princes bear the rule,But God, more mighty, governs kings themselves.”

Soon after the return of the King and Queen of Navarre to their own kingdom, Henry II. of France died, leaving the crown to his son Charles, a feeble boy both in body and in mind. As Charles was but ten or twelve years of age, his mother, Catharine de Medicis, was appointed regent during his minority. Catharine was a woman of great strength of mind, but of the utmost depravity of heart. There was no crime ambition could instigate her to commit from which, in the slightest degree, she would recoil. Perhaps the history of the world retains not another instance in which a mother could so far forget the yearnings of nature as to endeavor, studiously and perseveringly, to deprave the morals, and by vice to enfeeble the constitution of her son, that she might retain the power which belonged to him. This proud and dissolute woman looked with great solicitude upon the enterprising and energetic spirits of the young Prince of Navarre. There were many providential indications that ere long Henry would be a prominent candidate for the throne of France.

Plutarch’s Lives of Ancient Heroes has perhaps been more influential than any other uninspired book in invigorating genius and in enkindling a passion for great achievements. Napoleon was a careful student and a great admirer of Plutarch. His spirit was entranced with the grandeur of the Greek and Roman heroes, and they were ever to him as companions and bosom friends. During the whole of his stormy career, their examples animated him, and his addresses and proclamations were often invigorated by happy quotations from classic story. Henry, with similar exaltation of genius, read and re-read the pages of Plutarch with the most absorbing delight. Catharine, with an eagle eye, watched these indications of a lofty mind. Her solicitude was roused lest the young Prince of Navarre should, with his commanding genius, supplant her degenerate house.

At the close of the sixteenth century, the period of which we write, all Europe was agitated by the great controversy between the Catholics and the Protestants. The writings of Luther, Calvin, and other reformers had aroused the attention of the whole Christian world. In England and Scotland the ancient faith had been overthrown, and the doctrines of the Reformation were, in those kingdoms, established. In France, where the writings of Calvin had been extensively circulated, the Protestants had also become quite numerous, embracing generally the most intelligent portion of the populace. The Protestants were in France called Huguenots, but for what reason is not now known. They were sustained by many noble families, and had for their leaders the Prince of Condé, Admiral Coligni, and the house of Navarre. There were arrayed against them the power of the crown, many of the most powerful nobles, and conspicuously the almost regal house of Guise.

It is perhaps difficult for a Protestant to write upon this subject with perfect impartiality, however earnestly he may desire to do so. The lapse of two hundred years has not terminated the great conflict. The surging strife has swept across the ocean, and even now, with more or less of vehemence, rages in all the states of this new world. Though the weapons of blood are laid aside, the mighty controversy is still undecided.

The advocates of the old faith were determined to maintain their creed, and to force all to its adoption, at whatever price. They deemed heresy the greatest of all crimes, and thought—and doubtless many conscientiously thought—that it should be exterminated even by the pains of torture and death. The French Parliament adopted for its motto, “One religion, one law, one king.“ They declared that two religions could no more be endured in a kingdom than two governments.

At Paris there was a celebrated theological school called the Sorbonne. It included in its faculty the most distinguished doctors of the Catholic Church. The decisions and the decrees of the Sorbonne were esteemed highly authoritative. The views of the Sorbonne were almost invariably asked in reference to any measures affecting the Church.

In 1525 the court presented the following question to the Sorbonne: “How can we suppress and extirpate the damnable doctrine of Luther from this very Christian kingdom, and purge it from it entirely?“

The prompt reply was, “The heresy has already been endured too long. It must be pursued with the extremest rigor, or it will overthrow the throne.“

Two years after this, Pope Clement VII. sent a communication to the Parliament of Paris, stating,

“It is necessary, in this great and astounding disorder, which arises from the rage of Satan, and from the fury and impiety of his instruments, that every body exert himself to guard the common safety, seeing that this madness would not only embroil and destroy religion, but also all principality, nobility, laws, orders, and ranks.”

The Protestants were pursued by the most unrelenting persecution. The Parliament established a court called the burning chamber, because all who were convicted of heresy were burned. The estates of those who, to save their lives, fled from the kingdom, were sold, and their children, who were left behind, were pursued with merciless cruelty.

The Protestants, with boldness which religious faith alone could inspire, braved all these perils. They resolutely declared that the Bible taught their faith, and their faith only, and that no earthly power could compel them to swerve from the truth. Notwithstanding the perils of exile, torture, and death, they persisted in preaching what they considered the pure Gospel of Christ. In 1533 Calvin was driven from Paris. When one said to him, “Mass must be true, since it is celebrated in all Christendom;” he replied, pointing to the Bible,

“There is my mass.” Then raising his eyes to heaven, he solemnly said, “O Lord, if in the day of judgment thou chargest me with not having been at mass, I will say to thee with truth, ‘Lord, thou hast not commanded it. Behold thy law. In it I have not found any other sacrifice than that which was immolated on the altar of the cross.’”

In 1535 Calvin’s celebrated “Institutes of the Christian Religion” were published, the great reformer then residing in the city of Basle. This great work became the banner of the Protestants of France. It was read with avidity in the cottage of the peasant, in the work-shop of the artisan, and in the chateau of the noble. In reference to this extraordinary man, of whom it has been said,

“On Calvin some think Heaven’s own mantle fell,While others deem him instrument of hell,”

Theodore Beza writes, “I do not believe that his equal can be found. Besides preaching every day from week to week, very often, and as much as he was able, he preached twice every Sunday. He lectured on theology three times a week. He delivered addresses to the Consistory, and also instructed at length every Friday before the Bible Conference, which we call the congregation. He continued this course so constantly that he never failed a single time except in extreme illness. Moreover, who could recount his other common or extraordinary labors? I know of no man of our age who has had more to hear, to answer, to write, nor things of greater importance. The number and quality of his writings alone is enough to astonish any man who sees them, and still more those who read them. And what renders his labors still more astonishing is, that he had a body so feeble by nature, so debilitated by night labors and too great abstemiousness, and, what is more, subject to so many maladies, that no man who saw him could understand how he had lived so long. And yet, for all that, he never ceased to labor night and day in the work of the Lord. We entreated him to have more regard for himself; but his ordinary reply was that he was doing nothing, and that we should allow God to find him always watching, and working as he could to his latest breath.”

Calvin died in 1564, eleven years after the birth of Henry of Navarre, at the age of fifty-five. For several years he was so abstemious that he had eaten but one meal a day

At this time the overwhelming majority of the inhabitants of France were Catholics—it has generally been estimated a hundred to one; but the doctrines of the reformers gained ground until, toward the close of the century, about the time of the Massacre of St. Bartholomew, the Protestants composed about one sixth of the population.

The storm of persecution which fell upon them was so terrible that they were compelled to protect themselves by force of arms. Gradually they gained the ascendency in several cities, which they fortified, and where they protected refugees from the persecution which had driven them from the cities where the Catholics predominated. Such was the deplorable condition of France at the time of which we write.

In the little kingdom of Navarre, which was but about one third as large as the State of Massachusetts, and which, since its dismemberment, contained less than three hundred thousand inhabitants, nearly every individual was a Protestant. Antony of Bourbon, who had married the queen, was a Frenchman. With him, as with many others in that day, religion was merely a badge of party politics. Antony spent much of his time in the voluptuous court of France, and as he was, of course, solicitous for popularity there, he espoused the Catholic side of the controversy.

Jeanne d’Albret was energetically a Protestant. Apparently, her faith was founded in deep religious conviction. When Catharine of Medici advised her to follow her husband into the Catholic Church, she replied with firmness,

“Madam, sooner than ever go to mass, if I had my kingdom and my son both in my hands, I would hurl them to the bottom of the sea before they should change my purpose.”

Jeanne had been married to Antony merely as a matter of state policy. There was nothing in his character to win a noble woman’s love. With no social or religious sympathies, they lived together for a time in a state of respectful indifference; but the court of Navarre was too quiet and religious to satisfy the taste of the voluptuous Parisian. He consequently spent most of his time enjoying the gayeties of the metropolis of France. A separation, mutually and amicably agreed upon, was the result.

Antony conveyed with him to Paris his son Henry, and there took up his residence. Amidst the changes and the fluctuations of the ever-agitated metropolis, he eagerly watched for opportunities to advance his own fame and fortune. As Jeanne took leave of her beloved child, she embraced him tenderly, and with tears entreated him never to abandon the faith in which he had been educated.

Jeanne d’Albret, with her little daughter, remained in the less splendid but more moral and refined metropolis of her paternal domain. A mother’s solicitude and prayers, however, followed her son. Antony consented to retain as a tutor for Henry the wise and learned La Gaucherie, who was himself strongly attached to the reformed religion.

The inflexibility of Jeanne d’Albret, and the refuge she ever cheerfully afforded to the persecuted Protestants, quite enraged the Pope. As a measure of intimidation, he at one time summoned her as a heretic to appear before the Inquisition within six months, under penalty of losing her crown and her possessions. Jeanne, unawed by the threat, appealed to the monarchs of Europe for protection. None were disposed in that age to encourage such arrogant claims, and Pope Pius VI. was compelled to moderate his haughty tone. A plot, however, was then formed to seize her and her children, and hand them over to the “tender mercies” of the Spanish Inquisition. But this plot also failed.

In Paris itself there were many bold Protestant nobles who, with arms at their side, and stout retainers around them, kept personal persecution at bay. They were generally men of commanding character, of intelligence and integrity. The new religion, throughout the country, was manifestly growing fast in strength, and at times, even in the saloons of the palace, the rival parties were pretty nearly balanced. Although, throughout the kingdom of France, the Catholics were vastly more numerous than the Protestants, yet as England and much of Germany had warmly espoused the cause of the reformers, it was perhaps difficult to decide which party, on the whole, in Europe, was the strongest. Nobles and princes of the highest rank were, in all parts of Europe, ranged under either banner. In the two factions thus contending for dominion, there were, of course, some who were not much influenced by conscientious considerations, but who were merely struggling for political power.

When Henry first arrived in Paris, Catharine kept a constant watch over his words and his actions. She spared no possible efforts to bring him under her entire control. Efforts were made to lead his teacher to check his enthusiasm for lofty exploits, and to surrender him to the claims of frivolous amusement. This detestable queen presented before the impassioned young man all the blandishments of female beauty, that she might betray him to licentious indulgence. In some of these infamous arts she was but too successful.

Catharine, in her ambitious projects, was often undecided as to which cause she should espouse and which party she should call to her aid. At one time she would favor the Protestants, and again the Catholics. At about this time she suddenly turned to the Protestants, and courted them so decidedly as greatly to alarm and exasperate the Catholics. Some of the Catholic nobles formed a conspiracy, and seized Catharine and her son at the palace of Fontainebleau, and held them both as captives. The proud queen was almost frantic with indignation at the insult.

The Protestants, conscious that the conspiracy was aimed against them, rallied for the defense of the queen. The Catholics all over the kingdom sprang to arms. A bloody civil war ensued. Nearly all Europe was drawn into the conflict. Germany and England came with eager armies to the aid of the Protestants. Catharine hated the proud and haughty Elizabeth, England’s domineering queen, and was very jealous of her fame and power. She resolved that she would not be indebted to her ambitious rival for aid. She therefore, most strangely, threw herself into the arms of the Catholics, and ardently espoused their cause. The Protestants soon found her, with all the energy of her powerful mind, heading their foes. France was deluged in blood.

A large number of Protestants threw themselves into Rouen. Antony of Bourbon headed an army of the Catholics to besiege the city. A ball struck him, and he fell senseless to the ground. His attendants placed him, covered with blood, in a carriage, to convey him to a hospital. While in the carriage and jostling over the rough ground, and as the thunders of the cannonade were pealing in his ears, the spirit of the blood-stained soldier ascended to the tribunal of the God of Peace. Henry was now left fatherless, and subject entirely to the control of his mother, whom he most tenderly loved, and whose views, as one of the most prominent leaders of the Protestant party, he was strongly inclined to espouse.

The sanguinary conflict still raged with unabated violence throughout the whole kingdom, arming brother against brother, friend against friend. Churches were sacked and destroyed; vast extents of country were almost depopulated; cities were surrendered to pillage, and atrocities innumerable perpetrated, from which it would seem that even fiends would revolt. France was filled with smouldering ruins; and the wailing cry of widows and of orphans, thus made by the wrath of man, ascended from every plain and every hill-side to the ear of that God who has said, “Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.”

At last both parties were weary of the horrid strife. The Catholics were struggling to extirpate what they deemed ruinous heresy from the kingdom. The Protestants were repelling the assault, and contending, not for general liberty of conscience, but that their doctrines were true, and therefore should be sustained. Terms of accommodation were proposed, and the Catholics made the great concession, as they regarded it, of allowing the Protestants to conduct public worship outside of the walls of towns. The Protestants accepted these terms, and sheathed the sword; but many of the more fanatic Catholics were greatly enraged at this toleration. The Guises, the most arrogant family of nobles the world has ever known, retired from Paris in indignation, declaring that they would not witness such a triumph of heresy. The decree which granted this poor boon was the famous edict of January, 1562, issued from St. Germain. But such a peace as this could only be a truce caused by exhaustion. Deep-seated animosity still rankled in the bosom of both parties; and, notwithstanding all the woes which desolating wars had engendered, the spirit of religious intolerance was eager again to grasp the weapons of deadly strife.

During the sixteenth century the doctrine of religious toleration was recognized by no one. That great truth had not then even dawned upon the world. The noble toleration so earnestly advocated by Bayle and Locke a century later, was almost a new revelation to the human mind; but in the sixteenth century it would have been regarded as impious, and rebellion against God to have affirmed that error was not to be pursued and punished. The reformers did not advocate the view that a man had a right to believe what he pleased, and to disseminate that belief. They only declared that they were bound, at all hazards, to believe thetruth; that the views which they cherished were true, and that therefore they should be protected in them. They appealed to the Bible, and challenged their adversaries to meet them there. Our fathers must not be condemned for not being in advance of the age in which they lived. That toleration which allows a man to adopt, without any civil disabilities, any mode of worship that does not disturb the peace of society, exists, as we believe, only in the United States. Even in England Dissenters are excluded from many privileges. Throughout the whole of Catholic Europe no religious toleration is recognized. The Emperor Napoleon, during his reign, established the most perfect freedom of conscience in every government his influence could control. His downfall re-established through Europe the dominion of intolerance.

The Reformation, in contending for the right of private judgment in contradiction to the claims of councils, maintained a principle which necessarily involved the freedom of conscience. This was not then perceived; but time developed the truth. The Reformation became, in reality, the mother of all religious liberty.

Civil War.

1565-1568