Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Ryland Peters & Small

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

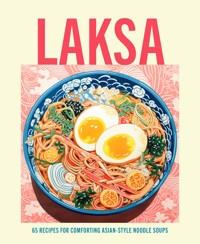

Enjoy this collection of laksa and other comforting noodle bowl recipes and get to know this popular south-east Asian dish in all its guises. Laksa is a delicious noodle soup consisting of thick noodles, swimming in a warming broth, packed full of fresh and fragrant ingredients with added toppings to add vibrant colour and interesting texture. For fans of spicy yet light-to-eat and reviving dishes, laksa really hits the spot. The origins of this often fiery dish are unclear, but it hails from Peranakan culture, which is based in southeast Asia and is a combination of Chinese, Malay and Indonesian influences. Which is why you can find anything from mild 'Chinese' type curries to sour tamarind varieties in these recipes. Curry laksa is the most often referred to type of noodle soup and is made from a coconut milk and curry paste base. Creamy, often fiery, intense flavours, with lashings of fresh chilli. Whereas Assam laksa is a much lighter version, made with a fragrant broth at its heart, full of tamarind and ginger flavours. Penang laksa is another version made with a tangy, sour fish broth. Slurp your way through this fantastic collection of recipes for laksa and other Asian-inspired noodle bowl recipes and find a dish to satisfy all of your cravings.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 142

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

LAKSA

LAKSA

65 RECIPES FOR COMFORTING ASIAN-STYLE NOODLE SOUPS

WITH RECIPES BY LOUISE PICKFORD & JACKIE KEARNEY

Senior Designer Megan Smith

Senior Editor Abi Waters

Creative Director Leslie Harrington

Editorial Director Julia Charles

Production Manager Gordana Simakovic

Indexer Vanessa Bird

First published in 2024

by Ryland Peters & Small

20-21 Jockey’s Fields

London WC1R 4BW

and Ryland Peters & Small, Inc.

341 East 116th Street

New York NY 10029

www.rylandpeters.com

Text © Kimiko Barber, Jordan Bourke, Ross Dobson, Nicola Graimes, Jackie Kearney, Claire and Lucy Macdonald, Theo A. Michaels, Louise Pickford and Ryland Peters & Small 2024 Design and photography © Ryland Peters & Small 2024

Note: Some recipes in this book have been previously published by Ryland Peters & Small. See page 144 for full text and photography credits.

ISBN: 978-1-78879-649-1

EISBN: 978-1-78879-665-1

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The authors’ moral rights have been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Printed and bound in China

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library. CIP data from the Library of Congress has been applied for.

Notes

• Both British (metric) and American (imperial plus US cups) are included in these recipes for your convenience; however it is important to work with one set of measurements and not alternate between the two within a recipe.

• All spoon measurements are level unless otherwise specified.

• All eggs are medium (UK) or large (US), unless specified as large, in which case US extra large should be used. Uncooked or partially cooked eggs should not be served to the very old, frail, young children, pregnant women or those with compromised immune systems.

• Ovens should be preheated to the specified temperatures. We recommend using an oven thermometer. If using a fan-assisted oven, adjust temperatures according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

• When a recipe calls for the grated zest of citrus fruit, buy unwaxed fruit and wash well before using. If you can only find treated fruit, scrub well in warm soapy water before using.

• All herbs used are fresh unless otherwise stated.

• To sterilize preserving jars, wash them in hot, soapy water and rinse in boiling water. Place in a large saucepan and cover with hot water. With the saucepan lid on, bring the water to a boil and continue boiling for 15 minutes. Turn off the heat and leave the jars in the hot water until just before they are to be filled. Invert the jars onto a clean dish towel to dry. Sterilize the lids for 5 minutes, by boiling or according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Jars should be filled and sealed while they are still hot.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

USEFUL INGREDIENTS

BASIC STOCKS

TOPPINGS, SAUCES & PICKLES

MEAT

POULTRY

FISH & SEAFOOD

VEGETABLE

VEGAN

INDEX

CREDITS

INTRODUCTION

I like to describe laksa as a celebration of flavours – spicy, fragrant, aromatic, rich, creamy, salty, sweet, sour and hot. But what is it?

Laksa is a southeast Asian noodle soup, the ultimate in fusion cooking and the culmination of Chinese, Malay and Indonesian influences. The exact origin is hard to pinpoint but there is little doubt that trade along the silk road as far back as the 16th century brought about a blending of cultures and cuisines Chinese noodle dishes and spicy southeast Asian curries merged into what we now call laksa. The word itself reveals a fusion of possibilities too, from the Hindi/Persian name for vermicelli noodles, ‘lakhsh’, to the Cantonese word ‘lét sá’, meaning ‘spicy sand’ and perhaps referring to the ground prawns/shrimp that form the base of many laksa soups.

Finding its home on the Malay Archipelago, laksa is at the heart of Peranakan cuisine – descendants of Chinese and Malay communities who are credited with its inception – its popularity spread throughout Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia and into Thailand, with each region introducing its own version given the use of locally sourced ingredients.

This brings us to the two main varieties of laksa. Perhaps the most identifiable and well known being curry laksa (also called laksa lemak or curry mee). Made from chicken or fish stock and a curry paste of herbs and spices including fresh or dried chillies/chiles, shallots, lemongrass, turmeric and galangal mixed with coconut milk. A whole host of other ingredients from prawns/shrimp, chicken, pork, beef, cockles and more can be added and just before serving puffed tofu and beansprouts are stirred through.

The soup is then simmered very briefly before being spooned over freshly cooked rice noodles. In fact, it is the noodles that make up the majority of the dish, with the rich coconut soup barely covering them. This is likely why it is referred to as curry laksa.

Although you will find different noodles depending on where you are, vermicelli rice noodles are the predominant variety. Hawker stalls in Penang for instance, often serve a version with a yellow wheat noodle called mee, or curry mee.

However, it is the abundance of vibrant, colourful and delicious accompaniments or garnishes that truly distinguish and define this wonderful soup. Little bowls of chillies/chiles, crispy shallots, lime wedges and aromatic Asian herbs such as Vietnamese mint, Thai basil and coriander/cilantro all add a burst of freshness. Sambal olek, a southeast Asian chilli sauce, adds an earthy chilli tang. Curry laksa is more than a bowl of soup, it is a magnificent feast in a bowl.

Then we come to the second variety of laksa, called asam laksa, a lighter style soup made from fish broth, ground fish, spices and aromatics. Added to these is tamarind water, that distinctive lemony sourness that gives this version its main characteristic – asam is in fact the word used for tamarind in the Malay language.

Unlike curry laksa it doesn’t include coconut milk and the broth is a lighter, golden brown colour with that wonderful sweet, sour and salty flavour. The soup is once again ladled over rice noodles and garnished with another array of wonderful ingredients including fresh pineapple, sliced cucumber, red onion and herbs.

Tongue tingling, aromatic and full of umami goodness, both varieties of soups, curry laksa and asam laksa, are the ultimate comfort food bowls.

USEFUL INGREDIENTS

All the following ingredients are readily available either in specialist Asian food stores or online.

FRESH RICE NOODLES – the best way of cooking fresh rice noodles is to steam them. However they can also be immersed briefly in boiling water, removed, drained and shaken dry. Bring a large pan of water to the boil, pop the fresh noodles in a steamer basket or pasta colander and dip into the water. Immerse for between 20 seconds and 1 minute depending on the thickness of the noodle. Drain well and divide between bowls. Best eaten immediately.

DRIED RICE NOODLES – fresh noodle sheets are dried and then cut either into a flat noodle or rice ‘stick’, or are extruded into long thin round noodles (like spaghetti). To rehydrate dried rice noodles for soups where they will sit in a broth and continue to soak up liquid, they need to be blanched rather than soaked. Bring a large pan of water to the boil, remove from the heat and add the noodles. They will take from between 2 minutes and 10 minutes to soft en until al dente, depending on the type and thickness. Be sure to test them from time to time.

Drain the noodles, shake dry and either divide between bowls and serve or refresh under cold water, shake dry and set aside until required. Rinse under hot water to serve.

DRIED MUNG BEAN NOODLES, CELLOPHANE OR GLASS NOODLES – these are thinner, and are slightly chewier than rice noodles. Rehydrate them in the same way as rice noodles. Drop them into a pan of just boiled water, off the heat and allow to soft en for between 2 and 5 minutes depending on the brand. Drain well and serve, or refresh under cold water for later use.

WHEAT NOODLES – although used less than rice noodles in laksa, they are served at hawker stalls and restaurants, particularly in Penang and Singapore where they are called mee. You can use any type of Asian wheat noodle, but I recommend thinner varieties. To rehydrate the dried wheat noodles, plunge them into a saucepan of boiling water and stir well to separate them. Simmer for 3–4 minutes until al dente. Drain well and use immediately, or refresh under cold water, drain and leave for later.

LAKSA PASTE Although it is possible to buy ready made laksa pastes, oft en of quite good quality, it will mean you are getting a ‘one-size-fits-all’ soup. This would be an injustice to you, me and the recipes in this book. Virtually all the laksa recipes in this book include their own fresh laksa paste, giving them their individual identity, oft en based on tradition, culture or specific regional ingredients and tastes.

However, this doesn’t mean you can’t pick and choose. I would suggest you give a recipe a go and if you love the result and want to stick to the same laksa paste, but experiment with other soup ingredients, then go for it. After all, laksas are the food of fusion.

You will find a couple of Thai recipes where the more traditional paste is replaced by a Thai red or green curry paste, as is often the case in Thai laksas. I also use my recipe for homemade sambal olek as the paste in one of the recipes, as it adds its own unique and rather intriguing flavour to the finished soup (Katong Laksa with shredded noodles, see page 90).

CORIANDER/CILANTRO ROOTS – rarely used outside of southeast Asia, coriander roots have a far deeper and more intense flavour than the leaves. They are an integral ingredient in a green curry paste. If you can’t find them, use a few coriander stalks and chop them finely.

DRIED SHRIMP – small shrimps or prawns are dried in the sun to concentrate their flavour and preserve them. If you have ever travelled in Asia you will have come across baskets of these little chaps drying in the sun (you are most likely to smell them before you see them). Oft en available in vacuum-sealed packs, either dried or dried and frozen, they are readily available from Asian stores or online.

DRIED WHITEBAIT – small dried fish, most oft en whitebait are used in Asian cooking to imbibe flavour. I prefer the clear broth and slightly more subtle flavour dried fish produce.

TOFU – I have added this info really to explain about puffed tofu, which are deep-fried squares of beancurd almost always part of a laksa. They are light and spongy with an almost hollow centre that allows them to absorb liquids so are ideal for soups. Once opened they should be kept chilled and used within three days. Other types of tofu in the book include soft tofu (not silken), which is available in most health food stores as well as Asian stores.

SAMBAL OLEK (OELEK) – this is a chilli spice paste native to Indonesian but used extensively throughout the Malay archipelago as well as Sri Lanka and India (another true fusion of flavours and ingredients). It is a more chunky style sauce and is used as a basic condiment in many dishes. It is quite delicious and you will find a recipe for homemade sambal olek on page 19.

SHRIMP PASTE – much like fish sauce, shrimp paste is used to flavour southeast Asian dishes. It is available plain or with other flavours added such as tomato, which I prefer to use for its slightly redder colour. Once opened it needs to be stored in the fridge and used within 1 month – but make sure it is well sealed or the rather pungent smell will permeate everything else within the fridge!

TAMARIND – the pod-like fruit of the Tamarind tree and its seeds are covered with a fleshy pulp from which tamarind concentrate is extracted. Used extensively throughout southeast Asia, tamarind has a distinctive sweet/sharp lemon flavour adding a wonderful sourness to savoury dishes. You can buy it whole in pods, as a block of hard pulp or as ready prepared concentrate. In this book I ask for tamarind water, which you can make from tamarind concentrate (a product that is readily available) to which I add water. It is easier and less messy to use than blocks of paste. Simply dilute the concentrate to a ratio of 1 part concentrate to 2 parts water. So 125 ml/½ cup tamarind concentrate will give you 250 ml/1 cup tamarind water, and so on.

VIETNAMESE MINT – with a flavour that is hard to pinpoint Vietnamese mint is also called Vietnamese coriander, Kesom leaf or even laksa leaf (it is an integral flavour in many laksa soup recipes). I would describe the flavour as being a combination of coriander/cilantro and mint, with a hint of hay thrown in for good measure. It is available from specialist retailers or online, otherwise I suggest you replace it with equal amounts of mint and coriander.

BASIC STOCKS

BEEF STOCK

This stock requires some good-quality beef bones, either marrow bones or something like short rib. If you are lucky your butcher will give you the marrow bones free of charge. The resulting stock should be clear and full of flavour.

1.5 kg beef marrow bones or short ribs

2 teaspoons white vinegar

2 teaspoons salt

5-cm/2-inch piece fresh ginger, sliced and bruised

1 onion, roughly chopped

2 garlic cloves, roughly chopped

a few white peppercorns

MAKES ABOUT 2 LITRES/QUARTS

Rinse the marrow bones or ribs and pat dry. Place in a bowl, cover completely with cold water and add the vinegar and salt. Leave to soak for 20 minutes. This will give you a clearer stock as it helps to reduce impurities in the bones, marrow or meat. Strain, discarding the water. Pat the bones dry.

Place the bones in a large saucepan with 4 litres/quarts cold water. Bring the water to the boil, simmer for 10 minutes removing any scum from the surface. Add the remaining ingredients and return to the boil. Lower the heat, cover and simmer gently for 2 hours until the stock is full of rich flavour.

Remove the beef bones and discard. Return the stock to the boil and simmer until reduced to about 2 litres/quarts. Strain the stock through a fine sieve into a clean pan and add a little salt, to taste. Leave to cool.

Use the stock as required, or chill in the fridge. The next day, scrape off the thick layer of fat that has set on top of the soup.

CHICKEN STOCK 1

The difference between a good dish and a great dish can oft en come down to something as simple as a good-quality stock base. I always try to make my own stocks, rather than buying them, especially for Asian recipes where other flavours are added. This first stock, where the whole chicken is cooked for 1½ hours in order to extract all the flavour from the meat and bones, renders the chicken flesh tasteless, and it is therefore discarded at the end (but if you happen to have a doggie companion, save the meat rather than bin it)!

1.5 kg/3¼ lb. chicken, preferably free range

1 bunch spring onions/scallions, trimmed and roughly chopped

1 head of garlic, roughly chopped

5-cm/2-inch piece of fresh ginger, sliced and bruised a pinch of salt

MAKES ABOUT 2 LITRES/QUARTS

Wash and dry the chicken and place in a large saucepan with the spring onions, garlic and ginger and pour over 3 litres/quarts cold water. Bring slowly to the boil, skimming the surface to remove any scum, cover and simmer gently for 1½ hours over a very low heat until the stock is full of flavour.

Strain and discard the chicken. Return the stock to the pan and simmer until it is reduced to 2 litres/quarts, then add a little salt to taste. Use or chill and refrigerate overnight. Discard the fat before use.

CHICKEN STOCK 2

Here the ingredients are exactly the same as version 1, but the chicken is poached for just 45 minutes before being removed from the liquid and left to cool at room temperature. The shorter cooking time means the chicken retains its flavour and can be used in recipes that require both stock and cooked chicken meat. Once the chicken is removed the stock is then simmered until it is reduced in volume.

1.5 kg/3¼ lb. chicken, preferably free range

1 bunch spring onions/scallons, trimmed and roughly chopped

1 head of garlic, roughly chopped

5-cm/2-inch piece of fresh ginger, sliced and bruised

a pinch of salt

MAKES ABOUT 2 LITRES/QUARTS