Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Open Borders Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A thriller of love and revenge, and an imaginative literary obituary for Kafka, bringing the Cold War to life, from Paris and Istanbul to West Berlin and Tel Aviv. "The novel vaults from interrogation to trial to poetic accounts of Ferdy's youth, rendered in Samî Hêzil's lyrical translation … Sönmez playfully expands Kafka's world in a literary experiment that encourages readers to reimagine the unfinished work of their heroes" Financial Times "The dialogue-led approach makes the book punchy and fast-moving, and brings some surprising twists before the end" Guardian "Did Max Brod commit a crime by not fulfilling Kafka's last will – to burn all his works? Burhan Sönmez is not a judge. He is only a scribe at the Last Judgment, recording the speeches of the parties. And he does his job brilliantly" Mikhail Shishkin "An inventive literary obituary for Kafka, perfect for both Kafka fans and lovers of historical literary page-turners in the vein of Anne Berest's The Postcard and Colm Toibin's The Magician" SA Examiner –––––––––––– West Berlin, 1968. As a youth uprising sweeps over Europe in the shadow of the Cold War, two men face each other across an interrogation table. One, Ferdy Kaplan, has shot and killed a student. Kommissar Müller, the other is trying to find out why. As his interrogation progresses, Kaplan's background is revealed piece by piece, including the love story between him and his childhood friend Amalya, their shared passion for Kafka, and the radical youth movement they joined. When it transpires that Kaplan's intended target was not the student but Max Brod, Franz Kafka's close friend and the executor of his literary estate, the interrogation of a murderer slowly transforms into a dialogue between a passionate admirer of Kafka's work, who is attempting to protect the author's final wish to have his manuscripts burned, and a police commissioner who is learning more about literature than he ever thought possible from a prisoner in his custody. In this gripping, thought-provoking tribute to Kafka, Burhan Sönmez vividly recreates a key period of history in the 1960s, when the Berlin Wall divided Europe. More than a typical mystery, Lovers of Franz K. is an exploration of the value of books, and the issues of anti-Semitism, immigration, and violence that recur in Kafka's life and writings. –––––––––––– "A homage to Franz Kafka, framed as the trial (of course) of Ferdy Kaplan … [Sönmez] queries how far one should go in the pursuit of what is important to us' The Times "The kind of book that will enthral a student and intrigue an Oxford don, thrill a worker on the factory floor and captivate a lifelong reader of Kafka" Lemn Sissay "Did Max Brod commit a crime by not fulfilling Kafka's last will – to burn all his works? Burhan Sönmez is not a judge. He is only a scribe at the Last Judgment, recording the speeches of the parties. And he does his job brilliantly" Mikhail Shishkin "A gripping tale of idealism colliding with history and moral uncertainty" Ava Homa, author of Daughters of Smoke and Fire "PEN International president Sönmez wrestles with fraught questions of loyalty and legacy in this contemplative literary thriller … Sönmez's sharp thematic layering and concise worldbuilding impress. This is a good bet for mystery readers seeking something off the beaten path" Publishers Weekly

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 126

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

3

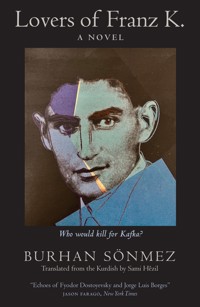

BURHAN SÖNMEZ

Lovers of Franz K.

Translated from the Kurdish by Sami Hêzil

5

“You loved him when he was alive and you loved him after. If you love him, it is not a sin to kill him. Or is it more?”

ernest hemingway,The Old Man and the Sea

“What! Would you burn my books?”

cervantes,Don Quixote

Photograph of Burhan Sönmez © Roberto Gandola

Contents

1

WEST BERLIN POLICE STATION

Berlin is a city divided by a wall down the middle. People living there in the summer of 1968 are staring at the long wall and are complaining about the weather getting warmer and buses running late.

The interrogation room in the basement of the police station in Friesenstrasse is cool. Stone walls spread damp in the room.

Kommissar Müller sits across from the suspect Ferdy Kaplan, lighting a cigarette and blowing out the smoke. He mutters to himself as he examines the papers spread on the desk.

Kommissar Müller: “Yes, the name used in the passport …”

Ferdy Kaplan: “Used? That is my real name, Ferdy Kaplan. But it does not matter.”

Kommissar Müller: “What does not matter?”

Ferdy Kaplan: “My name …”

Kommissar Müller: “Why not?”8

Ferdy Kaplan: “The explanation is on the papers in front of you. There you can find the answers to your questions.”

Kommissar Müller: “If only it were so, Herr Kaplan. We will get answers to some questions from you, won’t we, boys?”

[The other three police officers in the room laugh.]

Ferdy Kaplan: “You want to know where I got the gun and from whom, don’t you?”

Kommissar Müller: “We will get there. According to this file, you are staying in the Steglitz neighbourhood. Your mother is German, your father is Turkish. You appear to live in Istanbul, and you frequently visit Paris. Tell me first when you arrived in Berlin.”

Ferdy Kaplan: “I was born here. I am from here. Do not speak to me as if I were a foreigner.”

Kommissar Müller: “You are from here, but mostly you live elsewhere.”

Ferdy Kaplan: “That is not a crime. If you had lived in other places, perhaps you would have found yourselves better professions.”

[Ferdy Kaplan looks towards the police officer taking notes at the next table.]

Kommissar Müller: “We have no complaints about our profession. We are in a better situation than you are. Think of yourself, not us.”

Ferdy Kaplan: “I am happy with the chair I am in.”

Kommissar Müller: “How can you be so sure of yourself?”

Ferdy Kaplan: “I can tell you if you would like to hear.”

Kommissar Müller: “Oh, can you?”9

Ferdy Kaplan: “Yes, let me explain.”

Kommissar Müller: “Well then …”

Ferdy Kaplan: “Where would you like me to start?”

Kommissar Müller: “Why don’t you start with your origin? Kaplan is a Jewish name …

Ferdy Kaplan: “No, it is a popular surname in Turkey. It means tiger in Turkish.”

Kommissar Müller: “Tell me about your mother and father … People like you are rare.”

Ferdy Kaplan: “What do you mean?”

Kommissar Müller: “Suspects are mostly tight-lipped; they are not inclined to speak openly.”

Ferdy Kaplan: “People without belief behave that way. They are afraid of talking.”

Kommissar Müller: “Is there a belief in committing a crime?”

Ferdy Kaplan: “I don’t think I did commit a crime. I only did what I believed in. I did what had to be done.”

Kommissar Müller: “You did what had to be done, is that so? I am curious to know how you plan to explain all this.”

Ferdy Kaplan: “Everything I will say is already in your records, you don’t need to take notes. [Ferdy Kaplan glances at the police officer taking notes on the next table.] My mother was a Nazi supporter. My Turkish father shared her views. They died here in a Soviet bombardment in the last days of the war. My grandfather rescued me from the ruins. When my grandfather fell ill with his kidneys, he must have realised that he had not long to live, and he sent me off one year later to my father’s family in Istanbul.”10

For a boy of ten, who had come from a Berlin reduced to rubble, Istanbul was a magical place. Ferdy looked up at the ever-changing colours of the sky between the towers, domes and city walls. He immersed himself in the bustling bazaars and watched the joy in people’s faces. He listened to the sound of horse-drawn carriages, suburban trains and ferry boats. The sea, which he could not have dreamt of during the war, was on one side, and his grandparents were on the other. There was no fear of death. His grandfather and grandmother embraced their grandson as if he were a gift from God. They made him a bed on the floor of their room. At night they would tell him the fairy tales they had once told their own son and listen to Ferdy’s familiar breathing.

As Ferdy got better at speaking Turkish, he got used to the ridicule of some of the kids at school and the excessive attention of others. His German identity brought together two opposing sides of his life. His closest friend was Amalya. Unlike other girls, she would confront boys and protect Ferdy. Sometimes she would walk all the way home with him. One day, when Ferdy’s headaches returned, they sat down among the trees. Amalya touched Ferdy’s right temple, then kissed him on the cheek. It took a week for Ferdy to show the same courage and return the kiss. They often played away from the other children. They would hide among the rocks on the Kumkapı shore or by the old city walls in the Yedikule vegetable gardens. They would sing songs and read books together. Ferdy began to draw pictures again. He would draw the fishing boats, the flocks of seagulls, the setting sun. Amalya would ask why his drawings did not look like normal pictures. The boats would be awry, the wings of seagulls broken, and 11the sunlight blurred. Ferdy drew Amalya’s smiling face, her serene face, her sleepy face.

When Amalya was fifteen she moved to France with her mother. (As Ferdy Kaplan recounts his story, he makes no mention of Amalya.) Ferdy’s grandfather died in the same year. His heart stopped suddenly while he was in conversation with a customer at his fish stall in Kumkapı. They buried him in the cemetery by the old city walls at Topkapı. In the first year, Ferdy and his grandmother visited his grave every Friday. As time passed, they would visit him twice a year, on religious festivals. Life sped by. Ferdy tried to keep pace with it and grow up as quickly as possible. He would go to school in the mornings and help his grandmother on the fish stall in the afternoons. He began to learn about politics, listening in on the conversations of fishermen. The party founded by the conservatives had come to power. Politically the country was in disarray, with bridges being broken between the government and the opposition party. Nobody realised they were on the path to a military coup. Amalya, who had left the country when the new government was formed, returned ten years later to find the government shaken to its foundations. This was right at the peak of the protests. Despite the passing of so many years, Ferdy recognised Amalya in the crowd when he saw her at one of the demonstrations.

Kommissar Müller: “How did the political turmoil affect your life? Perhaps it is the reason you are now in a police station …”

Ferdy Kaplan: “Everything had an effect on me: the war that ruined Germany, the political unrest that shook Turkey, the events that rocked France …”12

Kommissar Müller: “France, yes. Were you in Paris during the protests in May?”

Ferdy Kaplan: “Everybody was there.”

Kommissar Müller: “So, when did you come here?”

Ferdy Kaplan: “I came a week ago.”

Kommissar Müller: “That is interesting. How could you leave Paris and come to Berlin when it was seething with the mad fever of youth? Why?”

Ferdy Kaplan: “But isn’t it, as you put it, seething here too?”

Kommissar Müller: “Did you return for that reason?”

Ferdy Kaplan: “You don’t need a reason to come home …”

Kommissar Müller: “If you killed someone, well, you will need a reason.”

Ferdy Kaplan: “I come to Berlin every year.”

Kommissar Müller: “So, did you come here directly, or did you stop off first in East Berlin?”

Ferdy Kaplan: “I did not go to the East at all.”

Kommissar Müller: “You mean you have never been there in your whole life?”

Ferdy Kaplan: “Since Berlin has been divided, I have not been to the East.”

Kommissar Müller: “Why? Having grown up in this city, have you never wondered how things are on the other side?”

Ferdy Kaplan: “When I come to Berlin I stay on this side of the border. Our house is here. My maternal grandfather’s grave is here.”

Kommissar Müller: “Your neighbourhood is close to the border, but you haven’t thought about crossing to the other side. Do you expect us to believe that?”13

Ferdy Kaplan: “I expect nothing from you.”

Kommissar Müller: “You killed a student, Herr Kaplan. We will see in what way it is related to the border and the other side of the Wall.”

Ferdy Kaplan: “It has nothing to do with the border and the Wall.”

Kommissar Müller: “It is our job to assume the opposite of what you are telling us.”

Ferdy Kaplan: “I am telling you the truth. Everything I say is as true as my identity and the crime I committed.”

Kommissar Müller: “Then why did you kill the student?”

Ferdy Kaplan: “Why do you keep calling him the student? Doesn’t he have a name?”

Kommissar Müller: “Don’t you know who he is? Are you a hired killer, murdering people not known to you?”

Ferdy Kaplan: “I do not kill for money.”

Kommissar Müller: “What would you kill for?”

Ferdy Kaplan: “May I have a cigarette?”

Kommissar Müller: “Later. For now, let’s see how the matter developed. [Kommissar Müller turns to the bearded police officer who is standing by the wall.] You tell us how it happened.”

Bearded Police Officer: “Yesterday evening, I was in front of the Central Library. I heard screams from the bus station across the street. I ran over. I saw this man, and a woman with him. Both were holding guns. They shot a university student waiting at the bus stop. The student fell lifeless to the ground. An elderly man at the bus stop was also injured in the shooting. When I shouted, the attackers started running. I followed 14and caught up with them. When Ferdy Kaplan realised they could not escape me, he stood behind a tree and shot at me. He wanted to give the woman with him a chance to disappear. I took cover behind a building and I shot at him. When he had no bullets left, I went over and arrested him. By this time the woman had got away.”

Kommissar Müller: “Is this how it happened?”

Ferdy Kaplan: “How can it be possible that your officer sees so clearly in the dark? It has no credibility. I was alone there. I don’t know the woman who was running beside me. She must be someone who panicked and started running.”

Bearded Police Officer: “We collected the bullet casings: the total number exceeds what your gun’s magazine can hold. That means not one gun was used but two. The other gun was carried by that woman, wasn’t it?”

Ferdy Kaplan: “I had two guns. When the magazine of the first gun was empty, I threw it into the bushes and used the second one.”

Bearded Police Officer: “We searched every corner, but found no other weapon. We are sure that woman was with you.”

Ferdy Kaplan: “If you are so sure, then speak to her.”

Bearded Police Officer: “We will speak to her when we catch her.”

Ferdy Kaplan: “That means you couldn’t catch her …”

[The room falls silent. They all look at one another.]

Kommissar Müller: “We will find her soon enough and we will question her too, in this room.”

Ferdy Kaplan: “You are wasting your time.”15

Kommissar Müller: “Don’t concern yourself with our time.”

Ferdy Kaplan: “If you are using your time wisely, then how have you not yet identified who that young student was?”

Kommissar Müller: “What makes you think we don’t know who he was? We know, as you do, that his name was Ernest Fischer. With regard to his studies, he was a good student. We gather he took part in a couple of demonstrations, but he does not seem to us so prominent a person as to be a target of such an attack. Is there anything you can tell us about him that we do not yet know?”

Ferdy Kaplan: “I would tell you if I knew.”

Kommissar Müller: “Were you involved in the other attacks against the students? For example, the attack that took place in April?”

Ferdy Kaplan: “Do you mean the attack in which Rudi Dutschke was injured? The suspect in that attack was caught, was he not?”

Kommissar Müller: “Then you must also have known the student who was killed last year.”

Ferdy Kaplan: “Benno Ohnesorg, yes.”

Kommissar Müller: “I see you take a close interest in these incidents.”

Ferdy Kaplan: “There is nothing unusual in that. Every detail appeared in the press, even in the Paris newspapers, and Istanbul reported the incident.”

Kommissar Müller: “That is correct. It made a little too much noise.”

Ferdy Kaplan: “But weren’t the police the perpetrators of the murder last year?”16

Kommissar Müller: “It may seem that way, but we suspect there is a network behind that incident that we are not yet aware of.”

Ferdy Kaplan: “It’s good that you suspect an unknown network among your own officers. But it was your attack on the student demonstrations that led to all this. Because the students were protesting against the Shah of Iran, you turned it into a battlefield. In order for the dictator of Iran to listen to Mozart’s ‘Magic Flute’ in the Alte Oper, you were at his full service …”

Kommissar Müller: “Our duty is to maintain public order, so that people can go about their daily lives.”

Ferdy Kaplan: “Is that why you killed a student?”

Kommissar Müller: “Why did you kill a student, Herr Kaplan?”

Ferdy Kaplan: “Those are completely different things.”

Kommissar Müller: “Oh, of course, you killed him on purpose, you did it in a prepared and well thought-out manner. In that case, they are entirely different things.”

Ferdy Kaplan: “If you knew the content of the matter, you wouldn’t speak of it in such terms.”

Kommissar Müller: “Indeed. The content of the matter. Explain that to us.”

Ferdy Kaplan: “All the explanations you need are written on the papers in front of you.”

Kommissar Müller: