Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Allen & Unwin

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

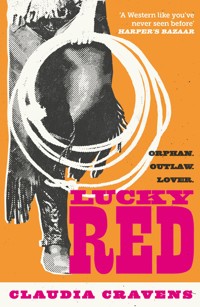

The USA Today bestseller! 'A good old-fashioned freight train of an adventure story' Sara Novic A feminist coming-of-age tale from a debut author - playful, feminist historical fiction for readers of Sarah Waters, Charles Portis and Anna North In the summer of 1877, Bridget is orphaned when her unreliable father succumbs to a snakebite as they're crossing the Kansas prairie. Arriving in Dodge City as a penniless orphan, she's quickly recruited for work at the Buffalo Queen brothel and befriends her bookish mentor Constance, securing her home and employment as the favourite of Sheriff's Deputy Jim Bonnie. As winter creeps in from the plains, female gunfighter Spartan Lee rides into town, and Bridget falls in love with her the moment their paths cross. Their affair threatens the balance of power at the Queen, but is interrupted when an old flame returns to the brothel, setting off a series of double-crosses that result in the destruction of the Buffalo Queen and a searing heartbreak for Bridget. Their lives in ruins, Bridget, Constance and Lila resolve to take revenge on those who wronged them - but will they succeed in their mission? In a misogynistic world of outlaws and gunfights, nothing is certain . . . A sharply realised, caustically witty and often moving revisionist depiction of frontier life that explores through its feminist heroine queer love, female friendships and the idea of a 'found' family in a page-turning romp of a female revenge thriller. 'This is storytelling that grinds its characters in its grip, then throws them into the air to take wondrous flight. I loved it to bits.' Shelley Parker-Chan 'Lucky Red made for such cinematic reading that I forgot it was a book!' Frances Cha

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 488

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Claudia Cravens has a BA in literature from Bard College andparticipated in Catapult’s yearlong novel generator. She lives in

New York City. Lucky Red is her first novel.

claudiacravens.com

X: @claudia_cravens

Instagram: @claudia.cravens

First published in the United States in 2023 by The Dial Press, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Published in hardback and trade paperback in Great Britain in 2023 by Allen & Unwin, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2024 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Claudia Cravens, 2023

The moral right of Claudia Cravens to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

No part of this book may be used in any manner in the learning, training or development of generative artificial intelligence technologies (including but not limited to machine learning models and large language models (LLMs)), whether by data scraping, data mining or use in any way to create or form a part of data sets or in any other way.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 676 9

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 675 2

Book design by Ralph Fowler

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House, 26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

CONTENTS

PART ONE | JOURNEY’S END

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

PART TWO | FIRST SNOW

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

PART THREE | HARD RIDING

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

PART ONE

JOURNEY’S END

CHAPTER 1

Some years ago, in Dodge, I was a sporting woman. This was before I took up my current trade, back when the prairie ran with cattle like a river runs with fish. It’s different now, of course, but then, so am I. I didn’t mind whoring—it can be good work in the right house—but it demands a great deal of keeping still, and I’m one of those itchy, fidgety sorts who’s always looking out the window or glancing toward the door, so it was only a matter of time until I had to move on. Most rambling types like to act as if they just woke up one morning and lit out, turning their backs to all and sundry, but this is just good storytelling. The truth is that making your own way happens piecemeal, like a baby who scoots, then crawls, then eventually toddles her way right out the cabin door where she’s as likely to be snatched up by coyotes as she is to seek her fortune; either way, once she gets loose, there’ll be no getting her back. All of which is to say that though I ended up a pretty girl in boy’s clothes, mounted like a woman and armed like a man, I started much smaller and simpler, and mostly alone.

Before I was a whore in Kansas, I was a poor drunkard’s daughter in Arkansas. My pa wasn’t a bad man, but it was far too easy for circumstances to get the upper hand on him. He called himself unlucky, but the losing hands dealt him were too frequent and too numerous to be mere turns of fate. I will admit that at times, events truly were beyond his control: first Ma died having me, then came the Brothers War, then he was on the losing side, and then he lost what was left of the farm to nursing his broken heart. But there were other misadventures that showed me, if not him, that there’s more to this life than luck, even bad luck.

First there were the mustangs, which he bought cheap and wild but lacked the will to break and was forced to sell off cheaper and wilder. Then the sheep flock, whose feed he let rot so they all went mad when they ate it. When we finally had to slaughter them, the screaming clatter of blood and terror seemed to thrust him back to some Virginian hellscape, for halfway through he threw aside his knife and shot the rest as fast as he could. In between, there were crates of plow-blades that wouldn’t hold an edge, barrels of discarded horseshoes, bales of kinked wire, all manner of flotsam that somehow always cost more than it made. He told himself he was getting by on his wits, when most of the time it was my willingness to scrub linens, tote water, and muck out horse barns that kept our souls inside of our bodies.

When I wasn’t hiring myself out on odd jobs, I was usually standing in the doorway of our small cabin on the edge of Fort Smith, from whence I watched the sunsets and periodically wondered if my pa had finally gone off for good. He was a restless soul, and his absences always mixed me up bad. There was the fear that comes from being alone—I was just sixteen and getting a little too ripe to be left unguarded—the snapping awake at every shift in the wind outside only to stare into the blue-black darkness and wait with bated breath for nothing to happen. There was the righteous fury at having been forgotten, as though I, his child and only living kin, was no more memorable than a cracked jug or a harness with a broken strap. This fury would surge up unannounced: suddenly I’d find myself slamming down buckets only to slosh water over my feet, wringing wet linens like turkey necks, shoveling horse shit like I was digging one grave to hold all of my enemies. And then there was relief, the sole proprietorship over my supper, the break from caring for the one person left on this earth who should have cared for me.

We always scraped together just enough to keep us in that little house at the far reaches of the town. I would watch for Pa’s return, going about my chores with half an eye on the cabin door, propped open during the warm months to admit the evening. I couldn’t tell you what he did when he was gone; he’d just disappear, leaving me to scratch out a few pennies doing other folks’ chores, and come back whenever he’d a mind to, half singing a loop of some dirty song he’d learned long ago in the army. He’d roar for cornbread or a fire, but when I couldn’t produce them he never got rough, just sad. The cold, blue reflection of the empty hearth would pierce through the fog of liquor in some way that the sun, or I, never could, and for a moment he would understand that he was a disgrace, supported by a daughter who pitched hay and scrubbed petticoats, and greasy, overlarge tears would well up in his eyes. If I didn’t move quickly to cheer him up with a song or a joke he’d set to weeping, which only required more soothing and petting to tame down. Once he started crying I’d have to smile and lie right into his face for hours on end, until he calmed enough to pull himself up into the loft, where he’d snore like a full crew of lumberjacks, or toss and shout when his dreams grew too lifelike. Sometimes, as I lay awake after a long evening spent dabbing at his cheeks, I wished he would’ve just smacked me instead. It was an ungrateful sentiment, but a beating would have been less humiliating than pretending I didn’t mind that I’d never been to school, that all I wore were baggy hand-me-downs, that the pretty town girls wouldn’t even talk to me.

At five days and counting, this was Pa’s longest spree yet: usually his drinking spells only lasted three, four days at most, but now as the sun was easing down to kiss the tops of the pines, he was still nowhere to be seen.

The sun dipped an inch lower, and at last I heard a rattling, then a scrape and holler.

“Bridget!” His voice came from up the track. My whole back prickled like a porcupine, that strange admixture of fury and relief that, once again, he’d survived his own recklessness.

“Where’s my little red hen?” came a second shout. I’d swung the kettle out from over the fire and was poking at the contents, willing the possum I’d earned chopping firewood to turn into stew so my stomach could cease its fistlike clenching.

“Come on, Henny Penny, I’m stuck!” he called out again, tacking a hoarse laugh onto the end.

With a stick of firewood I pushed the kettle of possum back over the flames, wiped my hands on my apron, and went outside. It was that hazy, uncertain time of day when the sky can’t decide whether to keep its day clothes on, and the lowest-hung tree branches blur together like a mist. A little way down the track that led past our house I found my pa perched on the seat of a rattly little buckboard I hadn’t seen before. There were two skinny mules attached, flicking their ears and staring wall-eyed into the trees. The wagon’s rear wheel was stuck on a rock, the work of a moment for anyone remotely capable.

“Where’d you get all this?” I said, hands on hips like I was his overworked wife rather than his underfed daughter.

“That’s none of your nevermind,” he said. He swayed as he spoke, focused on some fixed point in the air. I pursed my lips and went around behind the wagon to dig out the rock, scrabbling at it with my nails while my pa kept his seat, humming that same old song, something about a lady in a red dress. I pulled the rock loose—it stuck up high but wasn’t nestled in very deep—and the wagon jolted forward into our yard, leaving me to chase after.

“Where’d you get all this?” I asked again as I caught up to them behind the cabin. He clambered down and started unhitching the mules, tying them up at an empty trough.

“Traded for ’em!” he crowed.

My heart sank, mind searching wildly for something he could have traded away, even for such a lean prize as this.

“Traded what?” I asked him, tensed all over.

“Well, the man who gave ’em to me said he was looking for a gal to care for him and his aging mother,” he said, looking up at me. I stopped breathing, staring at him with my mouth wide open. He winked like the joke was obvious. “But I told him I was too attached to my girl to give her up on such terms. So he’s taking the cabin instead.” He lifted one hand and gestured at our little house.

“You gave him our house?” I gasped. I looked at the mules again. Their hip bones stuck out and one of them still had the shaggy remains of a winter coat patchworked over his flank. “For them?”

“And this,” he said, reaching into his jacket and pulling out a folded piece of paper, worn through where it had been folded and refolded too many times. He thrust it at me and I looked at the words, but I was poorly lettered and all I could pick out before he plucked it back from me was Kansas.

“Twenty acres, plus these two fine fellows. A fresh start, Bridget! A chance to change our luck!” The dusky shadows hid his face so that he was naught but a blue-gray silhouette. Instinct told me that to be less than jubilant would bring out a storm of tears and drown us both; I smiled and must have said something pleasant, for he drew me close and ushered me inside, complimented my treatment of the stringy, obstinate-tasting possum, and fell asleep still mumbling that song about some far-off pretty girl, long since forgotten.

Much to my surprise, traveling agreed with my pa: he just nipped at a bottle at night, stretched out alongside the fire right in the open air, snores reduced to horselike sighs, and for moments here and there I thought this might not have been a terrible mistake. As we bumped along, the cool forests of Arkansas gradually thinned and gave way to prairie under vast swathes of blue and white sky. It troubled me to come out from under the cover of trees; I’d lived my whole life in the shade and hadn’t realized how much I had come to rely on the pines for their uprightness, how under their canopy I’d felt held as by the great, green hand of God. As the woods dissolved, first into groves and then single, isolated trees, I found myself staring hard at them, suppressing the urge to wave sadly as though bidding old friends farewell, not that I’d had any. I began to wonder if each tree I saw would be the last, and to worry that I wouldn’t recognize that last one when I saw it.

Of course, there never was a real end to trees, just as there never is a real start to grass. And perhaps there should have been, for in the end it was our shared love of shade trees that got my pa killed. We were well into Kansas by then, just west of Abilene. Some speck on the horizon must have caught his attention, for he swung the mules off the wagon track and into open country, jolting me awake from where I’d been dozing in the mostly empty wagon bed.

“What is it?” I asked him, sitting up and rubbing the back of my head, which felt bruisy after so many days spent bumping in and out of sleep.

“A grove,” he said. “And maybe some water.”

He swung around and grinned at me. His hat had fallen forward so that I could only see his teeth, flat white and crowded together like passengers pressing toward a train door. “What do you say, Bridget, could you use a little shade?”

“I surely could,” I replied. I couldn’t see anything when I squinted past his shoulder, but I meant it all the same. We’d been under nothing but beating prairie sun for days; it seemed impossible that we could have traveled so far and still be surrounded by so little.

It was late afternoon by the time we came to the spring, nestled into a little dell that fed down to a creek bed, overhung by a stand of twisted cottonwoods. It wasn’t until we were under their shade that I saw the sod house dug into what passed for the hillside, a hairy facade with a silvery wooden door in the middle. I stayed in the wagon while Pa hopped down to take a look. The sun was getting lazy, and the light tilted into a golden syrup that spilled over his back; the grass was tall and yellow around his knees, sighing under the touch of a soft wind that ran over it like a hand over a piece of fine cloth; for the first time, I saw how such country could be beautiful.

Pa called out a hello, then rattled at the door when no one answered, but there came not a sound, not so much as a puff of dust.

“Ain’t no one here,” he said. “Let’s stop for the night.”

“In there?”

“No, let’s camp out here, just in case. Besides, I’ve grown fond of sleeping wild, ain’t you?”

“What if someone comes?” I said.

“And what if they do? Who would begrudge us, two simple travelers bunked out by a spring?” he said, crossing his arms and grinning at me again. Behind him the clear water of the spring rippled, sending up little stars of reflected sunlight, so I said nothing and climbed down. Our campsite twinkled to life as though laid out by fairies, so eager were we to stretch out and enjoy the cool shade and clear water. The hobbled mules huffed and snuffled as they drank, startling a prairie chicken who scuttled off into the brush before we could catch it. I waded straight into the spring to bathe my bare feet and Pa stretched out long at the base of a tree, pulling his hat down over his face. A fine breeze whispered over the grass and stirred the leaves of the cottonwoods; the sun dawdled overhead, and we drifted under its mindless gaze. Through the dancing leaves I watched the sky, enchanted and yet wondering how something that cared so little for me could so capture my attention. First it was a clear, reeling blue of staggering depth, but as I watched, the color drained away and was replaced by a deep gray as though the sky were turning to stone above us. I watched, fascinated, not realizing that the roiling texture it had taken on was cloud until the breeze suddenly turned cold, then whipped itself up stronger. I sat up when the first thick, heavy drops hit my face and shoulders. A new, fierce wind whipped my hair about my face like a blindfold.

“Pa!” I called out, but it was already dark, and he was already moving. We rolled up our meager camp and hustled toward the sod house. Its crumbling, hairy walls were lit white for a split second before the thunder rang out. I had never heard anything like it: the sound was physical, great hands clapping together as if we were two gnats they meant to smash. A fresh lashing of rain sent me barreling through the dark little mouth of the open doorway, the floor before me flashing around my own cutout shadow, and then the answer to the lightning’s question hit me like a whip between the shoulder blades and chased me into a corner where I curled up small in the darkness, waiting for the next crack and roll. We’d had thunderstorms in Arkansas, of course, but this was different, my first taste of real prairie weather that has nothing to give it shape or direct its madness. I pulled myself in closer and shivered.

“Come on now, be brave,” said Pa. “Ain’t nothing but a little lightning, and you ain’t been scared of nothing before this.”

For a moment I tightened from brow to shoulders with a sudden desire to spit back all the things I’d been afraid of those countless times he’d left me alone, all the things I prayed against before he came back. But there came another white flash and then the crack, louder this time. A sob burst out of me before I could stop it, and I crouched down, clutching the roll of blankets I’d grabbed on my run inside. What had possessed us to come to such a place?

Pa struck a match but made no further move to comfort me. Instead, he searched out a hearth, which he found at the back of the little house. “Why, some Samaritan has even left us some firewood,” he said. I heard sticks breaking and clattering against stone.

The next flash of lightning picked out the frame of a window straining to hold on to its ill-fitted shutter, and I was seized with fresh fear that it would burst open and that the storm, which I now viewed as a living, malevolent creature, would get inside.

“Well, if you ain’t going to help, I guess I’ll have to do everything,” said Pa in his half-joking way. I didn’t answer but instead kept my eyes fixed on the window. There was more rustling and shuffling behind me, and then a soft, yellowish glow spread out toward the door. The heat woke up a comforting musk of wet dirt and horses that clung to the walls; as my back warmed I felt the most animal part of my fear begin to dissipate, and a little calm pooled in my chest.

Though I was grateful to be in shelter, the sod house was even worse on the inside than it had looked from the outside. There was a ratty-looking pallet on one side of the hearth, away from the window. On the other, a table and two chairs that looked as though they’d sooner collapse than hold a body off the floor. There came another thunderclap, but this one was steadier, more of a long roll, and when it passed I could actually hear the rain outside, lapping over the grass. It was a pleasant sound, familiar. My hands allowed themselves to unclench, and I soon set to laying out our bedrolls, calming myself with work.

“There now, none the worse for wear,” said Pa. He came over and smoothed out the blankets, reaching out one hand to chuck me under the chin. He had deep lines around his mouth where he had spent most of his life smiling, but they hadn’t been smiles of happiness, and the resulting grooves were not handsome. Still, I could see he meant well, and smiled back. We shared some crackers and a wedge of cheese while Pa got to work on a bottle he’d bought two days earlier in Abilene—something about being cooped up seemed to bring out the urge in him. The thunder passed and the rain relaxed into a steady pace. Worn out with travel and panic, I pulled a blanket over my head and turned over to let sleep find me.

I woke to Pa’s screaming. It had happened plenty of times before, when he’d get caught in a dream of a lost battle, so as my eyes searched for anything at all in the pitch dark, my first sensation was annoyance. But then I realized this was different—these screams were high-pitched and strangled sounding. I knew my pa’s voice better than any other, and I’d never heard this shrill, twisted tightness before. It froze my heart in my chest even as I struggled to understand the cause. I groped in the blackness for matches and struck one: in its little circle of light I could see my pa writhing on the ground, clutching his throat and kicking out wildly with both feet. A big, blunt-nosed rattlesnake lifted its fangs out of his throat and sank them once again, this time into the back of his hand. Pa’s arm shot out to fling the snake away just as my match went out. In the dark I heard him jump up, still screaming; the next lit match showed him twisting like a dancer, flapping his arm until the snake finally lost its grip and flew off across the room, thudding softly against the sod wall before it scrambled away into the gap left by a missing hearthstone.

The match scorched my fingertips as it went out. I struck a third one and held it up to see that Pa had fallen to his knees, tears streaming down his face. His screams had died to a ragged sound somewhere between breath and sob. On hands and knees, I felt around for the stump of a candle and lit it as I crawled over the mess of tangled bedding to examine his wounds. I threaded one arm around his back and held up the candle. There was a bad bite in his neck, a pair of dark-red, seeping punctures that opened a door between him and the world. I clamped my lips down and pulled hard, filling my mouth with the taste of iron laced with bitter poison, turning to spit over my shoulder. By my third pull, his body had taken on a leaden aspect that chilled me worse than the screaming, worse than his raspy wheeze. I shifted my hold—he was not a large man, but still awkward to handle—and saw a faraway look moving into his eyes.

“Pa,” I said, surprised by the catch in my voice.

His eyes flickered up to mine like the ticking of a clock. “Just bad luck, Bridget,” he whispered.

I would have thought that two deep bites from a snake as big and mean as that rattler would kill a man outright, but it took almost a full day for Pa to cross over. At first light I dragged him outside and laid him under the cottonwoods, where the grass sparkled and the air was fresh as a whole field of daisies. The veins in his neck and arm stood out purple while red patches grew out from the bite wounds until finally, he just gulped like a catfish. I sat beside him and bathed his face with cool spring water, helplessly clutching at his hand while my pa slid away from me, one breath at a time, each growing more ragged and standing out more clearly against the rustle of the leaves dancing above us. All things being equal, it was a beautiful place to die.

Somewhere in the late afternoon, there came an exhale that was not followed by an inhalation. In the silence that followed, I sat halfway up, leaning forward as though it was only a moment’s suspense that I had to weather and not the soundless crossing over into a new, orphaned life. I stood up, dizzy, and stumbled on tingling, halfasleep feet back to the spring, wading in up to my knees before I sank down, submerged to the waist and gazing out across the empty plains. I looked at the dappled shadows on the water’s surface and found suddenly that I’d had my fill of shade.

Eventually I chilled and crawled out of the water. I sat up through the night, listening to the sound of my own breathing and feeling that it was both the loudest and the softest sound I’d heard in my life. There was no moon, but the stars picked themselves out one by one against the woolly blackness like a mourning dress, half-sewn, with silver pins still tucked into the seams. Each rising and falling of my chest lay heavy on me as I realized that I was truly alone now, that the periods in which I’d been abandoned previously both had and had not prepared me for this. I imagined my pa waving his hat and wishing me good luck as he placed me in the hands of fate, and felt a crack in the crust of resentment that had grown over my heart. I did not wish myself good luck, and I did not hope that Providence would treat me kindly. Instead, I told myself that it was up to me to keep my chest rising and falling, and that to do so I could not be governed by the world’s twists and turns, always whipped about by sad winds as he had been. I had never held out much hope for the places my life’s road would take me, for I was the daughter of a poor and feckless man, and in witnessing his thrashing about I had learned to adjust my expectations again and again. But I also found, as I sat under the black wing of the night sky, that I still had some fight left in me, and I made a promise to the indifferent stars above that I would live better than that wet-eyed corpse ever could.

CHAPTER 2

I buried Pa under the cottonwood trees. It took most of the day to dig: though I was strong from plenty of hired work, the prairie soil was hard-packed and laced overtop with such a thick net of sod that it took all I had to scrabble a shallow grave out of it. Before I pushed him in, I rifled Pa’s pockets. I found his wallet, which held thirteen dollars—about twelve more than I’d expected—and his pocketknife, which still held an edge. I didn’t find the folded piece of greasy paper that was supposed to have secured our future, but twenty acres of grass wouldn’t have done me a lick of good anyhow, even if the plot had been real, which I doubted it was.

I dragged and rolled the body into the hole I’d scraped out and piled dirt over it, having neither the time nor the patience to search for rocks. When I was done, mud-streaked and exhausted, I laid one hand upon the mound. I tried to think of something to say, but no words came to me, so I just patted it a couple of times and stood up.

It was afternoon already, but I was eager to move on. I didn’t know how far it was to the next town, and all I had was cheese and crackers. I didn’t let myself think about how miraculous it was that no one had come up to the spring yet. Neither did I mention to myself that coyotes would be along shortly to unbury my pa, nor the possibility of those same coyotes gnawing my own self down to bones that would bleach out real nice in the summer sun. I thought it best to keep my reasoning grounded in simple things like food rationing and miles traveled, at least until I got someplace.

The mules had bolted in the storm; though one had vanished without a trace, his partner had come through just fine, and Providence had even seen fit to keep him from wandering. He was just down the creek bed that fed from the spring, drinking the clear water and swishing his tail. Apparently pleased to see a familiar face, he came right up to me so that I could load him up with a bedroll and the remains of our food.

It’s hard to say how much time passed after I left the spring. At first, I stuck to the creek bed, following its serpentines approximately westward. The cover of brush and the nearness of water were so comforting that when, after some days’ wandering we came to the end of the creek, I all but wept to leave them behind. Still, I turned west out onto the plains. The mule and I traveled another day until we hit a wagon track running north-to-south. Having little idea where I was, I shrugged and chose south. Though I wasn’t sure what lay in that direction, I knew north was nothing but Nebraska, which was a much rougher place in those days than it is now.

Those days of traveling were dull in the extreme. I grew skinny and irritable from day after day with no one to talk to, while the mule grew bored and fractious, shuffling sideways when it came time to load him up. I alternated riding and walking, and we traveled without schedule or routine: when one of us got tired, we’d stop and rest. On waking, I’d nibble on some provisions and move us on as quickly as I could.

I hid at every sign of people, whether a dust cloud from a distant cattle herd, fresh horse tracks in the dust, or the creak and stamp of an ox-drawn wagon coming up behind us. Not a soul knew where I was, or even that I existed; I pushed us hard as I dared, hoping to get across the prairie unnoticed. Many years later I met a missionary who’d rode the plains awhile, and he told me that the prairie sky was nothing but God’s big blue eye. If that’s true, I wonder if He saw me, one little speck creeping like a mouse through that featureless stretch of His creation.

Finally, one morning I crested a small rise—I’d woken in the predawn chill and set out as fast as I could—and saw a cluster of smudgy buildings far off. I went hard that day until I had to stop, too tired to continue, but by the time the prairie shook itself awake the next morning, my mule and I were shuffling into Dodge City.

Dodge was in its prime then, brimming like a stoveful of boiling pots. As I came up the main street, every building seemed to be spilling over with people and sound and activity. After so many days with nothing to see but grass and sky and the twitching ears of my mule, it was a lot to take in. Two gray-faced cowboys supported a third between them who looked heavy as a grain sack; his legs spun crazily under his body as his friends maneuvered him toward a horse that swished its tail and sighed resignedly. Up above, I saw a girl in naught but a camisole lean her forehead against the windowpane, eyes shut. A storekeeper sweeping his chunk of boardwalk looked up and gave me a half nod, which I returned tersely. In the window behind him, I looked like a wraith. Through every window a pretty—or at least pretty-seeming—girl was combing her hair, blowing on a steaming cup of coffee, rolling her eyes at something said within. The sides of every building were lined with booted men, sleeping upright with their hats over their faces; before each one a saddled horse shifted patiently from foot to foot, blowing in the crisp air and nickering softly to each other. Farther off, I heard a train whistle before a blast of steam appeared like pipe smoke over the buildings, dissolving blue and ghostlike into the thin sky, while under it a steady rumble of cattle lowing and stamping was punctuated with the yips and whoops of cowboys already hard at work loading them up. It was completely overwhelming, and completely enchanting, unlike anyplace I had ever been.

That first day in town I sold the mule to a sod-buster who planned to take him straight back out to the plains. Though the sod-buster seemed a decent sort, I found I couldn’t bear to watch the mule be led away at the end of a rope. The sale brought my assets up to thirty-three dollars plus the worn-out bedroll and the pocketknife. I considered visiting the land office to try and inquire about the plot my pa had died supposedly possessing, but I couldn’t even formulate the question I would ask, or how I would know if the answer was correct.

I sold the knife for two more dollars and gave the bedroll to a ragman for fifty cents, and found myself for the first time in my life with more money than sense. My whole body ached, and I suddenly craved to be indoors worse than I had ever craved anything in the world. It was as if the miles had been waiting until the last possible moment to make themselves known through every bone that had carried me this far. The wind felt like sandpaper against my cheeks, the dirt from the street caking between my toes like mold on old bread.

Working my way south down the main street, I was turned out of seven hotels before I found one that would rent a room to a raggedy, barefooted orphan. I had never stayed in a hotel before, which must have been obvious for I was forced to pay an entire fortnight’s room and board in advance. Key in hand, I shut the door to my little room, and at the sight of a real bed—neither a roll of threadbare blankets nor a loud, itchy cornhusk pallet—I stood in the middle of the floor and wept. Then I lay down and slept clear through to the next morning, when I was woken by the thunk of the key fob falling from my balled fist.

I ran through every dime I had without ever once leaving the hotel. On waking each morning I’d slither into my dress, a hand-me-down that had started out too big in Arkansas and become a faded pink sack during my travels, and patter down to the dining room. The hotel was little more than a flophouse, but there was a real cook, of sorts, and I think he took pity on me. My days began with great, steaming mugs of coffee with enough cream to make my spoon stand upright, four or five fried eggs layered over thick slabs of toast spread with sun-colored butter, fat glossy sausages with chunks of peppercorn tucked here and there. I ate as though I were packing my soul back into my body, as though I would never be served again. I thrilled at every meat that wasn’t possum or squirrel or the meanest hen in a worn-out flock. I’d never mastered the baking of wheat bread, so every slice that crackled and puffed between my teeth was like a fresh start, a sign that I hadn’t been dreaming.

Momentarily sated, I’d drift back upstairs and send for a hot bath, ordering buckets of steaming water for hours until I wrinkled up like a little old witch. In those murky, soapy waters I alternated between tears and a buzzy, soft blankness, my head like a hive of woolen bees, letting the misery and terror of that prairie crossing and all that had come before it well up through my chest until it had no place to go but out through my face. When my tears were spent I stared at the sky outside my window or at my callused, crooked toes. As the days passed, I watched years’ worth of dirt soak out of them until they grew soft and pink, the nails whitening to milky crescents.

When I wasn’t in the tub—and often when I was—I was eating. Hunger wasn’t new, of course, but it had always been a source of worry. Now, with my meals paid ahead and the anonymous cook on my side, every whisper of appetite was of interest to me, an invitation to think about not what I lacked but what I would soon have before me. I ate accordingly: double portions of stew to be dabbed at with thick, crumbly biscuits; two or three chops at a time nestled in a lean-to shape against a hillock of steaming potatoes studded with salt crystals; greens boiled silky and toad-colored twining with beans that smelled of molasses and hid chewy burnt ends. I kept bright apples and stout wedges of cheese on my nightstand, let the big crumbs from hunks of cornbread pock into my bathwater, washed everything down with cool buttermilk. With each meal and each well and flow of tears, a bit of gnawing urgency lifted, and gradually I began to feel my feet on the ground once more. In the course of those two weeks, I quite literally ate myself out of house and home: on the fifteenth morning, the self-styled hotelier rapped on my door and demanded either more money or my room key. Having no choice, I turned over the key, loath to take to the streets once more. Now that I had tasted a life of full meals and relatively clean sheets, I hated to give it up.

Outside, I snarled at the dust that leapt up from the thoroughfare like a cloud of fleas to cling in all the deep, familiar places. Lacking any better ideas, I took up the work I knew: doing other people’s chores. For a month or so I scrubbed floors, chopped wood, and suffered mightily under the sour gaze of a Mrs. Mackey in her boardinghouse, which overlooked the cattle depot and stank of cow shit. She insisted that I wear a pair of her now-grown son’s old boots, which chafed and blistered me while their imagined cost came out of my wages. We hated each other immediately, and though she considered herself a Christian woman for keeping me out of the whorehouses, it only took a week for her to start clouting me with a broom handle whenever she’d a mind to. I tried to bear it as I had borne such things before, but the attic pallet was hard, the food tasteless and insufficiently portioned. More than that, I think something inside me was plumb worn out. I had already spent too much of my life hauling and scrubbing under the pinched face of some stingy matron, and Mrs. Mackey’s violent condescension turned out to be the last straw. One day I lost my temper, and when she reared back for a second blow with a stick of firewood I swung the soup ladle I was holding and caught her right on the point of her chin— next thing I knew, I was out on my ass.

For a day and a night I wandered Dodge, taking the place in anew. Though I maybe should have been scared—I was dead broke and fresh out of ideas—the activity that surged and swayed all around filled me with a giddy buoyancy. Everywhere I went, there was music in the air as each saloon’s piano strove to be the loudest and most cheerful; every few seconds I’d pass an open door that issued bursts of laughter and conversation like jets of steam from a locomotive. I clung to the shadows but couldn’t tear my eyes away. There was every type of person to be seen, though whores and cowboys dominated on the south side of the tracks. The cowboys all shifted from foot to foot just like their horses, while the whores flashed their eyes and showed their teeth, snuggling brightly corseted tits up into their tricks’ faces. The street I wandered alternated between mud slick and dust storm, while a rainbow of smells rolled out from between the buildings: now pipe smoke, now piss, now onions frying, all layered over a miasma of dung and cow hair that clung low to the ground. People were coming and going in every direction, and things didn’t start to slow until the first gray streaks of dawn crept up from a horizon that seemed very, very far off. By then my wanderings had brought me to the train depot, where I found an out-of-the-way bench and curled up around my empty stomach, too tired to be scared. I slept a few hours until the stationmaster rousted me out, and found myself once more adrift and hungry.

I spent the morning watching the hands work the cattle. There’s pleasure to be had in seeing a task properly completed, and despite the noise there was an order to it I admired. It seemed two herds had gotten mixed up into one pen, and the crew were cutting one out to load into boxcars bound for Chicago. There was a terrible racket of the stock lowing and hawing at each other, layered under the yips of the cowboys, who eased their mounts between the cows, shouting and popping at them with their quirts. The cowboys were young and friendly-looking, most not much older than myself, tanned and bright-eyed under their hats. They rode as easily as most people walked, as if each man and his horse were a single creature with four legs and two heads. Every now and then one would spot me watching and duck his chin; the bolder ones tipped their hats, and when I finally smiled back at one, his fellows exploded into a shower of hoots and joshing.

“Well, they sure like you,” said a voice over my shoulder.

I started and turned around to see a woman, still young, with black hair pulled up under a smart little top hat. She wasn’t tall, but she didn’t need to be; under her arched brows, deep-brown eyes held me in sway with a steady gaze that clearly ducked to no one. Her rouged lips looked like a piece of heart-shaped candy, complimented by a deep-red dress that looked far too fine to be worn out in all this dust. I’d never seen anyone so stylish in all my life.

“I . . . I suppose I don’t know,” I stammered, feeling very young and shabby before her, relieved to be shod.

She chuckled. “Oh, yes you do. They like you plenty, and what’s more you know it.” I said nothing, and she approached, closing the gap between us in two steps while she looked me up and down. She reached out for a loose lock of my hair, rubbing it between her gloved fingers as if I were a bolt of cloth she might buy. She was looking right into my face, scanning it carefully. I was used to having a woman look me over, but usually it was to judge whether I could lift her Dutch oven out of the fireplace. This one was looking for something else. Like a deer, I found myself getting very still, waiting for a sign as to what I should do next.

“You are a pretty thing,” she said. “That red hair of yours sure stands out.” She dropped the lock and grabbed my upper arm, running her hand down to my wrist with a series of light squeezes. “You’re skinny, though. We’ll have to feed you up. What’s your name?”

“Bridget,” I rasped.

“Bridget what?”

“Shaughnessy.”

“You a church-going gal, Bridget Shaughnessy?”

“No, ma’am, not especially.”

“Good.” She stepped back and took one more look at me, clearly making up her mind. “Well, Bridget, I’m Lila. You looking for work?”

“What kind of work?”

“What kind do you think? Pretty girl like you all on her own.”

I said nothing and toed at the dirt between us.

“You look hungry,” Lila continued. “Ain’t you ready to do a little sporting yet? Or do you want to wait a spell for your prospects to worsen?” She cocked her head like a crow fixing to split open a snail shell.

At that I looked up. “What do you mean?”

“I know we’re only just acquainted, but it ain’t hard to see you’re at the ass end of an ass-kicking,” she said. “Or do you have a wealthy suitor stashed up one of those ratty sleeves?”

“Don’t suppose I do,” I said, twisting my fingers together.

“What’s the matter, you disdainful of whoring?”

“Everyone has to eat,” I said truthfully.

“Yourself included.” She paused to let that sink in, while the scraps of a few sermons I’d heard here and there tussled with my empty belly.

“Tell you what,” said Lila. “You come on with me, say hello to Kate, and at least we can get a plate of food into you. I hate to see a girl starve, and you look just about ready to turn scarecrow if we don’t get some bacon into you. Maybe a couple of fried eggs, some biscuits? With blackberry jam?” She drew out the m of jam into a warm little hum, and when she cocked her head the other way I got my first taste of Lila’s wry, knowing smile. I remembered the promise I’d made to myself out by the spring and was ready to offer my assent, but before I could speak for myself, my stomach yowled like a cat getting stuffed into a gunnysack. Lila laughed.

“Come on, Bridget,” she said, and turned to walk away, beckoning me to follow. Unable to think of a reason not to, I trotted after Lila, out of the cattle yard, up the main drag, and into the Buffalo Queen Saloon.

CHAPTER 3

“Well, look at you, Strawberry Pie,” said Kate. Lila’s business partner tilted her head, appraising me such that I felt an urge to pull my lips back, prove that I had all my teeth. She looked older than Lila by at least ten years, with full eyebrows and a heavy jaw that came to a perfect square at the joint; gently waving hair was swept up into a pale brown cloud on top of her head. She patted my face and reached around to pull on the bit of twine at the end of my braid to work her fingers through my hair, spreading it loose over my shoulders. The touch was so intimate that it shocked me to stillness; Kate took a handful of my curls and lifted them up for a closer look, and for a moment I thought she was about to smell them. “Good eye, Lila,” she added as she stepped back. “She ought to do very nicely.”

I saw Lila stretch her neck to preen a little, though she said nothing.

“What about that Sallie, any word?” said Kate.

“Got a letter at the post office, said there was a spot of business to take care of, but she’ll be along soon as she can,” said Lila.

We were in the upstairs room of the saloon that served as Kate’s office, bedroom, and receiving parlor. Slow piano music seeped up through the floorboards like smoke. Hoping to hide my inexperience, I’d stolen but one or two glances as we’d passed through the barroom below and come away with fleeting images: afternoon sunlight glancing off rows of bottles and warming the polished wood of the bar, a couple of girls in red dresses sitting with their chins in their hands, unlit lamps whose globes were black with soot. As we passed the girls, Lila had paused to tug a loose lock of brown hair tumbling down the back of one girl’s skinny neck with a sharp admonition to tidy herself up, or didn’t she want to make any money tonight.

Now in the parlor Lila had retreated somewhat, letting her partner take over. The shades were drawn against the heat of the day; in the gloom I stood on the carpet before a settee whose crimson upholstery had only just begun to sprout loose threads around the edges, while Lila rummaged through a trunk of red dresses and white underclothes, a tumble of lace and calico from which she plucked up bits and pieces.

“It’s a good thing Lila found you before some other shady character came along,” said Kate. She circled me, leading with her hips rather than her legs to walk, so that her skirt swung in wide, lazy bell-rings that brushed over the floor. “We’re a lot fairer than most of the other jokers you’d meet out on the thoroughfare. Lucky for us too—our last redhead lit out for Chicago, though to be fair she was only pinkish,” she chuckled.

“And sickly to boot,” Lila added without looking up. “You sickly, Bridget?”

“Not a day in my life,” I piped, holding Kate’s eye. It occurred to me that she must once have been quite striking; now something in her seemed blurred, smudged like a newspaper photograph that had been thumbed over too many times. In looking me over she seemed to be relying more on experience than sharpness, but even this came as a respite, for I had known so little gentleness in my time.

Kate completed her circle and held me out at arm’s length, looking into my face again. “Have you done this type of work before?” she asked.

“Not as late,” I replied, trying to sound like a sophisticate rather than a liar. Out of the wind, the still air was like a blanket and I could feel myself getting warm.

Kate raised one eyebrow. “No matter,” she said. “These cowboys are going to eat you up—you look like all their fellows’ little sisters. Still, we’d best give you a tryout, make sure everything’s where it ought to be.” She looked over at Lila. “Whose turn is it?”

“Langley’s,” said Lila, holding up a crumpled chemise. She spat on the cloth and rubbed at a spot with her thumbnail. “But I think he’s indisposed today.”

Kate sighed. “Roscoe, then?”

Lila nodded. “I’ll fetch him.” She draped the chemise over the back of one of Kate’s parlor chairs and opened the door, letting in a breath of piano music and the smell of bacon frying downstairs, and stuck her head out. “Roscoe!” she shouted.

“Yeah?” came a man’s voice from below.

“Come on up here!” Lila answered. The piano music stopped and I heard boots clomping up the stairs. My stomach, already knotted, pulled tighter.

“What’s going on?” I asked Kate.

She wrinkled her brow slightly in bemusement. “My dear, we can’t just take you in and turn you out without so much as a taste for the house.”

“Turn me out?”

She shook her head and turned to Lila. “She is greener than a Texas springtime, isn’t she,” she said, with another chuckle and a small shake of her head.

Lila shrugged. “Well, do we or don’t we need a redhead?”

“We do,” said Kate. She looked at me. “Don’t mind her. She just likes to remind me that we run a brothel, not an orphanage.”

“Damn right we don’t,” said Lila, casting a sharp eye at me. Roscoe appeared in the doorway. He had the strong shoulders and rounded middle that mark all men whose days of heavy work are behind them, with a dark walrus mustache and brows that seemed to glower, but when I looked at his eyes they were soft, and I realized he was just squinting at me in the half dark, clutching his hat in both hands like he was about to ask my ma if I could come out and play when my chores were done.

“Well, Roscoe, what do you think?” said Lila.

“She’s a pretty one all right,” said Roscoe.

“We think so too, but we oughtn’t to turn her out untried. Care for a slice of pie?” At being talked of so crassly I felt a new fold crease in my stomach but held my ground; whatever they had in mind, it scared me far less than going back out onto the street with an empty belly.

“Well hell, I never say no to that,” said Roscoe. He set his hat down on the end table and strode right past me to the bed, loosening his sweat-mottled cravat as he went. I twisted to watch him go by. He had his shirt pulled up halfway over his head before anyone said anything.

“Well, go on, Roscoe won’t bite,” said Kate.

My feet didn’t seem to want to lift just yet. “You want me to . . .”

“You want to work? We won’t beg, you know. It’s up to you.”

I looked back over at the bed, next to which stood Roscoe, now with his naked back to me, showing a shoulder-thatch of dark hair. I felt a strange splitting in that moment; my head filled with a loud, even buzz that blocked out all thought, while my feet carried me toward the bed like a fish on a line. I still wonder about that moment, in which I acted but have no recollection of volition. Maybe it was the way that the still air felt warm around me as the wind outside never could, or maybe it was the first time I’d really acted at no one’s mercy but my own, or maybe I was just hungry. Whatever it was, it pulled me, and as I walked toward the bed I was only mildly surprised to feel my hands reaching up behind me to unbutton my dress.

“Just to the petticoats will do,” said Lila from behind me. “You ain’t gotta get all the way down to your skin.”

“Leave them be,” Kate said.

“Well, we ain’t got all day.”

“Don’t spoil the moment.” I glanced back to see Lila roll her eyes while Kate swatted gently at her arm. Though still mostly clothed, I’d never felt more naked in my entire life.

Roscoe must have seen it in my face. He was out of his shirt and trousers and stripped down to the waist, the sleeves of his union suit dangling like offal around his knees while its lowest buttons strained over a bulge I tried not to notice. He held out his hand to me and I took it, letting him guide me onto the counterpane like a princess who’d been married off to a wild boar. “Don’t fret about them,” he said. He shoved my petticoats up around my waist and leaned back to let me wriggle out of my drawers. The open air on my snatch made me jump a little, but not nearly so much as Roscoe’s hamsteak palm, which was soft and slightly damp as it traveled up my thigh and he pulled himself forward.

I’ll admit the sensations were strange that first time through, but once he got into a rhythm, Roscoe was easy to ignore. There was a cluster of knotholes on a ceiling beam that I gazed at absently while he set his post; together they looked like the face of a badger, or a spray of daisies in a jar. At one point I lifted my head and looked over Roscoe’s heaving shoulder, where I caught glimpses of Kate and Lila, who were watching us intently from the settee.

“Act like you like it,” Roscoe whispered in my ear.

I wasn’t quite sure what acting like I liked it entailed, so I took a guess, wrapping one arm around his fuzzy shoulder and placing the other on the back of his head, and kissed the side of his face. It seemed to work: he pushed himself in deeper, forcing a series of corresponding little moans out of my mouth, and I saw Kate and Lila exchange the smallest of glances just before he was brought to bear by my innocent charms and, with a pause and a sigh, slumped off to one side.

I lay on the bedspread while he wriggled back into his clothes. He picked up his hat on the way out and tipped it to me, then Kate and Lila, from the doorway. I propped myself up on my elbows and pushed back a lock of stray hair that his sweat had glued to my forehead.

“Can I have some dinner now, please?” I asked.

They cackled in harmony at my question. “What did I tell you?” said Lila, grabbing at Kate’s arm. “Did I find us a natural or didn’t I?”

“Not quite,” said Kate. “A real natural would have got herself fed before, not after.”