Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: edition chrismon

- Kategorie: Religion und Spiritualität

- Sprache: Englisch

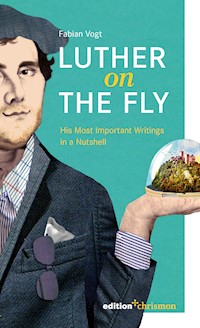

Can words change the world? Certainly! No one proved this to be true as impressively as Martin Luther did. His writings changed the course of religious and cultural history in Germany, Europe, and the world. Martin Luther sparked the Reformation primarily with his intelligent and inspiring writings. But what do they say exactly? Fabian Vogt presents the Reformer's most important teachings in a brief summary that is as entertaining as it is informative and contains everything from the '95 Theses', to the treatise 'On the Freedom of a Christian', to Luther's speech at the Diet of Worms. Martin Luther hat die Reformation vor allem mit seinen mitreißenden und klugen Schriften ausgelöst. Aber was steht da eigentlich drin? Fabian Vogt fasst die wichtigsten Schriften des Reformators zusammen. Kurz und knackig, informativ und unterhaltsam geht es von den "95 Thesen" über die "Freiheit eines Christenmenschen" bis zur Rede auf dem Reichstag zu Worms.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 139

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Fabian Vogt

LUTHER

on the

FLY

His Most Important Writings in a Nutshell

Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbiographie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the internet at http://dnb.dnb.de.

© 2017 by edition chrismon in the Evangelische Verlagsanstalt GmbH Leipzig

This work, including all of its parts, is protected by copyright. Any use beyond the strict limits of copyright law without the permisson of the publishing house is strictly prohibited and punishable by law. This applies in particular to reproductions, translations, microfilming, and storage or processing of the entire content or parts thereof in electronic systems.

This book is printed on ageing resistant paper.

Cover: Hansisches Druck- und Verlagshaus, Frankfurt a. M., Anja Haß

Coverillustration: Oliver Weiss, Berlin

Innengestaltung und Satz: Makena Plangrafik, Leipzig

E-Book-Production: Zeilenwert GmbH 2018

ISBN 978-3-96038-088-7

www.eva-leipzig.de

‘STAND UP FIRMLY, SPEAK UP CLEARLY, SHUT UP EARLY.’

Martin Luther

PREFACE

Can words change the world? Of course they can! No one has given more impressive proof of that than Martin Luther, the courageous, uncompromising and passionate 16th century Reformer who became one of the founders of the modern age with his daring writings.

At the end of the Middle Ages, Luther demonstrated the unbelievable explosive force of words. The history of the Reformation is an example of the way rousing phrases can, under certain conditions, shake up a society more thoroughly than new laws, amazing technologies or entire armies – and how easily a person with imagination can jump into another, better world with a single leap.

It is no surprise, then, that some of Luther’s writings have been added to the UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. They tell the fascinating story of a plucky monk who successfully took up the fight with all the powers that were at his time – the pope, the Emperor, the nobility and with all who were – in his opinion – adhering to a wrong and life-stifling way of thinking.

But Luther did not fight with a sword. His weapons were words, written as well as spoken, loud as well as soft, erudite as well as provocative and polemic, deadly serious as well as full of jest. A mighty wielder of words, the unconventional thinker from Wittenberg called the ruling system in question until no one could get away from his outrageous outspokenness. The result was the Reformation, a great ‘process of renewal of the Christian faith’ – and with it came a far-reaching transformation of church and state whose beneficial after-effects we still feel today. Thank God!

Thus, the best way to get familiar and understand Martin Luther’s importance is to get to know and understand his great writings: those trailblazing publications that topped the 16th century bestseller lists for years, even decades, although they were not called that at the time.

The book you are holding in your hands now will introduce you to typical examples from Luther’s most important writings in a way that is short and to the point, accessible and easy to understand, informative and highly entertaining. It will serve you an array of ‘Lutheran’ appetizers, as it were, a kind of Wittenberg starter plate. With only the best ingredients of course: from the famed ‘95 Theses’ to ‘On the Freedom of a Christian’ to Luther’s speech at the Diet of Worms which made it irrevocably clear that this celebrated popular hero was fundamentally challenging the way the world was ordered.

My hope is that after reading this book, you will not only have discovered what made – and makes – this extraordinary spiritual awakening so very powerful, but also acquired a taste for relating the explosiveness of some of Luther’s revolutionary statements to our everyday life in the 21st century. Join the discussion!

Besides, wouldn’t it be nice to be able to let your profound knowledge of history shine through at parties and receptions from now on? ‘Oh, it’s interesting that you say that. By the way, Martin Luther wisely remarked something very like that in his „Open Letter on Translating” …’ But no … you would never stoop so low of course.

I am convinced that it is wholesome to talk about Luther and the things he has to say to us. For the Reformer’s wisdom still inspires us today and invites us to look with curiosity and discernment at seemingly immovable structures and fixed habits. Or, as the later Reformers themselves put it with respect to the theological impulses of their movement: ‘Ecclesia semper reformanda!’ – The church is always in need of reformation. In other words, the change must never stop.

If that is true, then it must have been clear to Luther from the beginning that every one of us is called to contribute to this renewal. At least he once wrote: The Church needs a reformation. But this reformation is not only the pope’s or the cardinals’ responsibility. It is the responsibility of the whole of Christendom, or even better, of God alone. Only he knows the hour of reformation.

This means that if you start thinking about Luther, you will find yourself encouraged to become part of the ongoing process of Reformation. Maybe it was just this suggestive invitation to become a ‘revolutionary of love’ yourself that made his writing so luminous.

Before introducing you to a selection of Luther’s writings, I would like to take you on an excursion into his writing workshop to take a look at the circumstances in which this diverse body of work came into being.

In a second introductory chapter, I then want to take you through the most significant stages of his life, for in the case of this Wittenberg professor it is highly instructive to be aware of the biographical background of his writings and to be able to relate them to the history of the Reformation.

After that, I will dare tackle twelve of Martin Luther’s works and writings considered by scholars as milestones of Reformation history, giving you a highly condensed overview of their most important statements and concerns. In a nutshell, as it were, or compact, to use a modern expression.

This is a risk, of course. I know that well. Especially as I am taking the liberty of summarizing the texts. And summarizing always entails leaving things out. It entails bundling information and elementarizing. But that doesn’t matter, I think. 500 years ago, after all, Luther himself was keen on making complex matters understandable for everyone. And if this gives you an appetite for reading the original work in its entirety – go for it! It’s worth it.

This book, though, is called ‘Luther on the Fly’ – and for good reason. For reading Luther in the original is not a quick affair. Believe me! I have tried that thoroughly. Therefore, allow me to occasionally simplify, paraphrase or otherwise illustrate the theological connotations. Luther himself once described this approach thus: If you preach about the article of justification, people will sleep and cough; but if you start offering stories and examples, they will perk up both ears and listen diligently. Doesn’t that sound encouraging?

Incidentally: For centuries, scholars have been trying to give an account of how Martin Luther might have managed to set so many people in motion in his time. What was his secret? Well, aside from the fact that we know today that the great reviver did have a dark side too and was, in the end, only one piece in the great jigsaw puzzle of the Reformation – albeit a pretty big one and most of all the one who got the whole thing started – it probably was his personality that contributed a lot to his life’s work.

Put another way: Behind almost everything Luther ever published lay a personal life experience. Most of all the experience of a man driven by the fear of hell who suddenly discovered the freedom of heaven – a God-seeker who experienced the leap from primordial fear to a primal sense of trust as a personal new birth.

And as the Church of his time had not been able to help him in his desperate wrestling with his fears (it rather did the opposite), Luther took it upon himself to renew this institution. By doing that, he called ancient hierarchies into question that also pertained to worldly structures of power.

What is essential, then, is that behind all these social upheavals there was the ‘converted’ Reformer’s ardent desire to make the ‘Good News’ of the love and mercy of God accessible to as many seekers as possible. Or, as he himself put it: Making a sad, despondent person happy is more than conquering a kingdom. In this, of course, Luther was closely emulating his model Jesus Christ, who also changed history by changing the hearts of people.

Thus, the Lutheran answer to my question at the beginning – ‘Can words change the world?’ – is really: ‘Yes, because they can change people’s hearts.’ Well, if such a power dwells in written words, then it is a pleasure to interact with them.

Wishing you a stimulating read,Fabian Vogt

CONTENTS

Cover

Title

Copyright

Luther and His Writings

Luther and the Reformation

The Twelve Most Important Works

The 95 Theses (1517)

On the Freedom of a Christian (1520)

On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church (1520)

To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation (1520)

On Worldly Authority (1523)

Open Letter on Translating (1530)

The German Mass and Order of Service (1526)

On Good Works (1520)

The Estate of Marriage (1522)

To the Councilmen of All Cities in Germany that they Establish and Maintain Christian Schools (1524)

Order of a Church Treasure, Advice how to Handle the Spiritual Goods (1523)

Speech at the Diet of Worms (1521)

A Look Forward

Sources

LUTHER AND HIS WRITINGS

The importance that writing had for Martin Luther is illustrated by a nice anecdote that people still like to tell about him:

When the Reformer had to hide on the Wartburg in the summer of 1521 after the Church had excommunicated him and the Emperor had laid a ban on him in the edict of Worms, which made him an outlaw, he frequently was under the impression, so it is told, that he was being pursued by demons and evil spirits.

One day as he was sitting at his desk working as usual, the devil himself suddenly appeared in his little cell, teasing and tempting the already despondent fugitive. In his fear and panic, Luther is said to have grabbed his inkpot – which seems the closest projectile he could find – and hurled it in rage at the satanic confuscator, thereby succeeding, it seems, to drive him away.

For centuries, the ink stain resulting from this throw, or some sort of ink stain anyway, has been preserved and looked after on the Wartburg for the benefit of visitors – just because it is such a charming anecdote to tell.

Luther himself, though, never claimed to have thrown that inkpot. His words that inspired others to invent this picturesque story were: I drove the devil away with ink. What a great phrase, isn’t it? I drove the devil away with ink. What the Reformer meant, of course, were his writings. All the things he had committed to paper with pen and ink: his letters, open letters, lectures, sermons, pamphlets and translations.

To put it in modern and somewhat psychological terms: Luther manages through writing to canalize those things that profoundly concern, trouble and worry him. In other words, his writings were, among other things, a successful antidote against despair, a wholesome self-therapy. It is certainly not a bad approach to deal with one’s challenges and temptations, as Luther sometimes called those dark moments, by sorting out all the seemingly menacing thoughts and turning them into sagacious publications.

Without reading too much into Luther’s phrase about ink and the devil, it is certainly characteristic of his writings that, as mentioned above, one senses in every single line how personally their subject matter concerns him, how much he wrestled and existentially battled with questions that deeply mattered to the unintentional “instigator” himself.

If you look at the sheer volume of Luther’s publications, you get an inkling how much these “devilish” intrigues must have haunted him: about 350 printed writings, hundreds of sermons, 2,500 letters and almost 7,000 after-dinner speeches have been documented. And we probably can hardly imagine how effective particularly his printed writings were in Germany at the time.

It’s true! Experts estimate that in the twenties and thirties of the 16th century, the works of Luther made up the majority of all books sold. Any author’s dream. One huge print run after another came out of the presses – a deluge of hotly demanded literature, augmented by a constant supply of unauthorised reprints.

Furthermore, by medieval standards the spiritual “reviver” can be called a media superstar. Luther was probably indeed the first celebrity in history to have their printed portrait circulating extensively in the whole Empire. Thus, from the North Sea coast down to Lake Constance, every woman and every man knew what the famous, rebellious theologian looked like. Something like that had never happened before.

In view of that it is true, of course, that Luther owed his breakthrough, among other things, to the relatively recent invention of book printing. Since Johannes Gutenberg had laid the foundation for modern book printing and invented the printing press in Mainz around 1450, it had become possible to copy and distribute texts in large numbers. Until then, every book had to be copied manually in a painstaking process that took months.

Nevertheless, this provided only the technological means for distribution. Another circumstance proved just as essential for the great resonance Luther’s writings found: that he was able as a scholar, theologian and preacher to express himself in a clear, true-to-life and entertaining way. The things he published were plainspoken, bold, challenging and highly eloquent at the same time. Luther had such an overwhelmingly impressive way with words that he left indelible marks in the German language. It is fair to say that Luther was one of the most important initiators of New High German.

Most people do not realize, for example, how many idiomatic phrases and figures of speech still prevalent today go back to Martin Luther: ‘Hochmut kommt vor dem Fall’ (‘pride comes before the fall’), ‘Wer anderen eine Grube gräbt, fällt selbst hinein’ (‘harm set, harm get’), ‘Perlen vor die Säue werfen’ (‘casting pearls to the swine’), ‘Im Dunkeln tappen’ (‘grope in the dark’), ‘Die Haare zu Berge stehen haben’ (‘having one’s hair stand on end’), ‘Ein Buch mit sieben Siegeln’ (‘a book with seven seals’) or ‘Wer den Pfennig nicht ehrt, ist des Talers nicht wert’ (‘take care of the pennies, and the pounds will look after themselves’). Indeed, if it weren’t for this creative reformer of language we would have to do without such glorious words as ‘Bluthund’ (‘bloodhound’), ‘Feuertaufe’ (‘baptism of fire’), ‘Machtwort’ (literally ‘power word’, an authoritative statement to settle a matter), ‘Lockvogel’ (literally ‘luring bird’, a decoy) and many others. And when he really got going, he could even get a little coarse, as for example with his famous saying, From a sad arse comes no happy fart. Graphic enough for you?

Luther had an extraordinary feeling for language, perhaps because he was himself a singer, played the lute and the flute, and as a poet over the years penned 36 hymns still known in our time. Songs whose lyrics full of fighting spirit contributed much to the spreading of the Reformation as they were a sort of pamphlets for the illiterate.

Furthermore, this wordsmith developed an amazing feeling for graphic illustrations. The writer Bertolt Brecht once remarked that he loved Luther’s works especially because of his ‘gestural language’. What he meant was that often the Wittenberg professor’s turns of speech make us feel as if we could actually see the gestures that accompany them. For example, in Luther’s translation of the Bible, when he writes, Wenn dein Auge dich ärgert, dann reiß es aus und wirf es weg (If your eye annoys you, rip it out and throw it away).

One of the biggest strengths of Luther’s writings, furthermore, is that for all their scholarliness and accuracy they always strove to be understandable. What good would it have done to publish the most erudite specialist literature that only a small minority gets? That’s why what the Reformer once said very pointedly about his sermons is equally true for his theological writings: When I come to the pulpit, it is my intent to preach only to the farmhands and maidservants. I would never stand up for Doctor Jonas’ or Melanchthon’s1