19,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

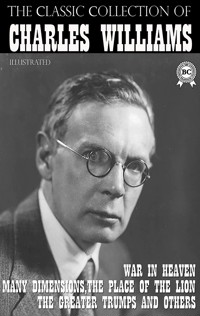

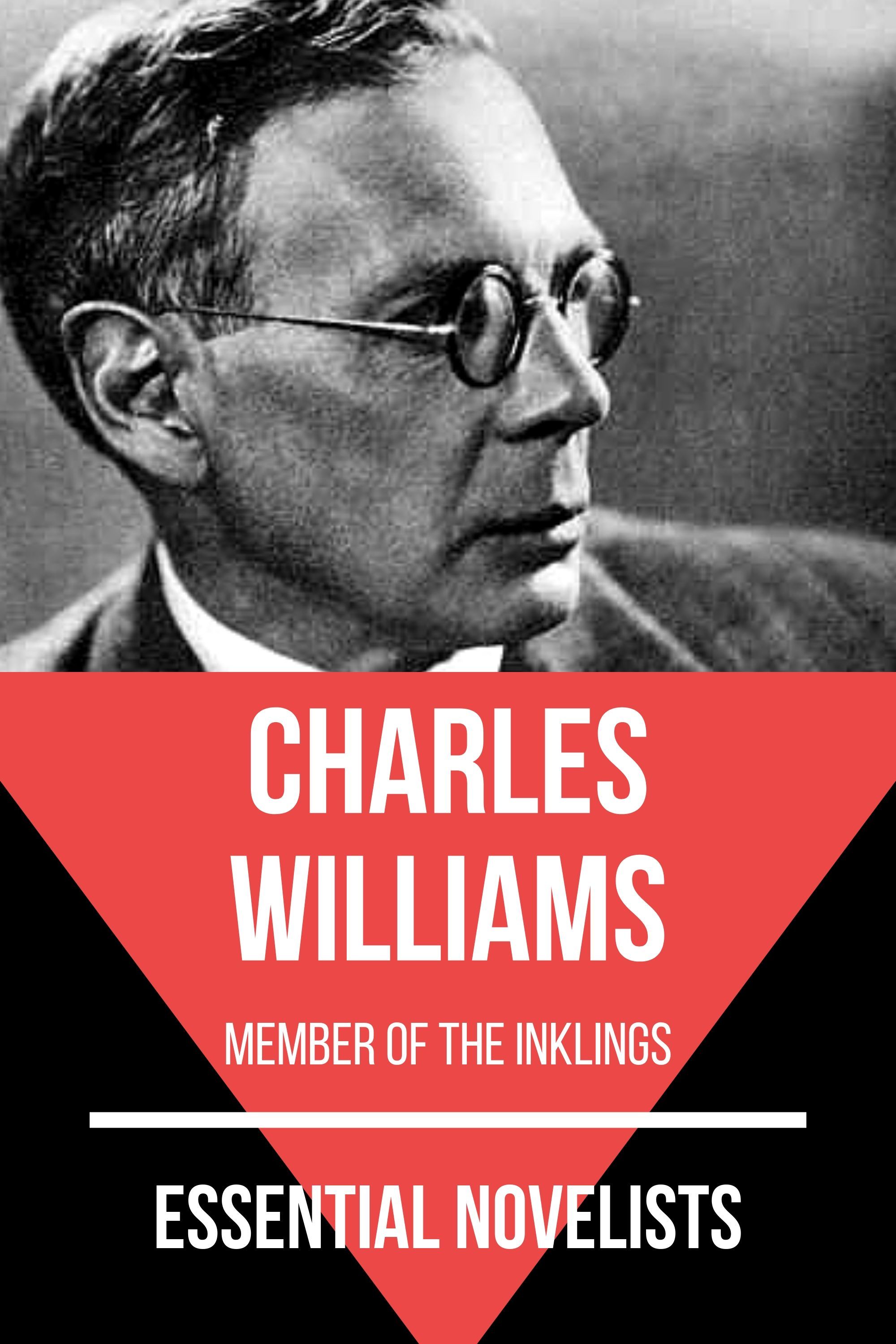

Financial magician, flamboyant politician, minister in both world wars, press baron, serial philanderer, Winston Churchill's boon companion in the dark days of 1940-41 and in his later years, Max Beaverbrook was without a doubt one of the most colourful characters of the first half of the twentieth century. Born and brought up in the Scottish Presbyterian fastness of northeast Canada, he escaped to make his fortune in Canadian financial markets. By 1910, when he migrated to Britain at the age of thirty-one, he was already a multimillionaire. With a seat in the House of Commons and then a peerage, he came to know all the senior figures in both British and Canadian politics. In acquiring the Daily Express, he not only built it into a news empire but used its considerable influence to campaign for his own pet causes. As Charles Williams's sweeping biography shows, Beaverbrook was loved and loathed in equal measure. Nevertheless, Williams brings to life a rounded character, with all its flaws and virtues. Above all, it is a story of eighty years of entrepreneurism, political dogfights, wars, sex and grand living, all set in the rich tapestry of the dramatic years of the twentieth century.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

For Jane

CONTENTS

When the Devil wants to make major mischief, he sends for Max Beaverbrook.

When he wants to make minor mischief, he sends for Evelyn Waugh.

PROLOGUE

Lady Diana Cooper, in her day one of London’s leading society lionesses, described Max Beaverbrook as ‘this strange attractive gnome with an odour of genius about him’.1 She was far from alone in her admiration. Many others were similarly captivated: a good number of minor lionesses, more than a few journalists and historians, a scattering of politicians and, above all – but perhaps with a greater sense of realism – Winston Churchill himself. They all succumbed to the charm, sense of mischief and sheer ebullience of the man.

By contrast, there were also those who saw the darker side of the character. Indeed, had she been less mesmerised by him even Lady Diana might have been forgiven for adding ‘and from time to time with more than a hint of malice’. Certainly, the list of those who openly disliked him is impressive: Kings George V and VI, Clement Attlee, Stanley Baldwin, Lords Alanbrooke and Curzon, Hugh Dalton, Ernest Bevin, as well as a large segment of the Canadian political and industrial establishments. Furthermore, Clementine Churchill’s attitude towards him, unlike that of her husband, was one of ‘lifelong mistrust’.2 (She also, by the way, thought him an unreconstructed lecher.) As one of the few still alive who knew Beaverbrook in person, if only in her capacity as Churchill’s secretary in his later years, my wife still describes him as ‘somebody you would instinctively walk away from’.3

It is not for the biographer to take sides in such a controversy, however animated it was and, to some extent, still is. His task is to tell the story of a life and, in doing so, to illustrate – and, if possible, explain – how and why it gave rise to the sometimes explosive expressions of opinion which his subject has provoked. As it happens, there is no shortage of material to hand. The Beaverbrook story is, after all, one of continuing fascination: over eighty years of high (and low) finance, political dogfights, wars, conspiracy, media wrangles, sex and grand living, all of it threading through the dramatic years of the first half of the twentieth century. Yet the biographer, any biographer, has to be careful. It is too easy to slip into other rhythms, either too laudatory or too critical or – worst of all – simply too boring. Caution thrown aside, following Beaverbrook has been an absorbing journey on a human roller-coaster. But from time to time the author, while carefully fastening his seatbelt, has had to prepare himself for moments of queasiness. It may be that the reader will now have to do the same.

Notes

1 Quoted in Philip Ziegler, Diana Cooper (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1981), p. 94.

2 Mary Soames, Clementine Churchill (London: Cassell, 1979).

3 Author interview with Miss Jane Portal, 6 June 2014.

CHAPTER 1

THE BRUNSWICKER

Spem reduxit1

For the King’s Men, 1783 was the decisive year. They had remained loyal to the British Crown through the turbulent early years of the American Revolutionary War, had fought in militias alongside the Redcoats, had been scorned by the Revolutionaries (‘Patriots’, they called themselves) and had seen their houses burnt down, their property confiscated and their friends tarred and feathered. But, as much as the Revolutionaries were aggressive and unforgiving, the King’s Men had no great love for the British. Like the Patriots, they, too, objected to the arrogance of their colonial masters and to the taxes they were obliged to pay without the possibility of argument. Nevertheless, King George III was still the King to whom they had sworn allegiance, and therein lay their problem. As it happened, a Maryland lawyer, Daniel Dulany, was ready with a solution. ‘There may be a time when redress may not be obtained,’ he wrote. ‘Till then, I shall recommend a legal, orderly, and prudent resentment.’2 The language suited its purpose. What was offered was a fence of procrastination to be sat on; and the King’s Men, or Loyalists as they became known, duly sat on it.

Although they were joined under one metaphorical flag, the Loyalists were far from a homogeneous group. There were tenant farmers in upper New York, Dutch traders in New Jersey, German smallholders in Pennsylvania, Quakers and Anglican clergy in Connecticut, a few Presbyterians in the southern colonies and a large number of Iroquois Indians, in all amounting to around one fifth of the total non-slave population of the Thirteen Colonies of some two and a half million. For such a disparate bunch it is no surprise to find that there was little formal organisation. In short, the only glue that kept them together was caution, tenuous loyalty to the British Crown – and fear.

Fear became the major element in the glue after the surrender of Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown, Virginia, in October 1781. Word spread quickly that the British were to sue for peace. The question then for the Loyalists was how the victorious Revolutionaries would treat their defeated compatriots. At first, the outlook was promising. In April 1782, negotiations between representatives of Great Britain and the nascent United States opened in a small hotel in what is now the Rue Jacob in the Saint-Germain quarter of Paris. It was quickly agreed that the United States should be free and sovereign. There was then an extended argument over boundaries – the American negotiators wished to swallow up the Province of Quebec – much wrangling over fishing rights off the coast of Newfoundland, debate about the validity of contracts on either side and agreement about the release of prisoners of war.

The debates, as might be imagined, were more than usually protracted, and little percolated through to the anxiously waiting transatlantic audience. It took weeks for news to travel, by post coach, then sailing ship and then coach again. But by early 1783 the main lines of agreement had become clear. In particular, the provisions of what became Article 5 of the final treaty started to circulate as rumour – that the Congress of the Confederation of the United States would agree to recommend to state legislatures that they should provide for the restitution of confiscated properties to their rightful owners, the Loyalists. That was all very well. The difficulty was that this was to be no more than a recommendation. State legislatures were free to ignore it. Indeed, as the year went on, it became apparent that a number of states would be exercising their right to do so.

By the time the Treaty of Paris was signed in September 1783, some Loyalists were already deciding that their future did not lie within the newly independent Thirteen Colonies. The majority, in fact, remained, particularly those who had acquired property and social status – or family ties with Patriot relations. However, some sixty thousand, according to one estimate, emigrated, half to the south and the friendlier political climate of Florida and half to the north. The Iroquois Indians were summarily expelled from the state of New York and ended up in the west of what became Canada. The white émigrés (together with their slaves) made moves to settle in the British colonies of Upper Quebec and Nova Scotia.

Those who made for Nova Scotia immediately encountered a problem. The past had been troubled and Nova Scotia itself was only just in the process of calming down. The century to date had witnessed six wars between the British colonists and the French and Indians. Subsequently, the Treaty of 1763 had ceded most of the old French colony of Acadia and all of the peninsula of Nova Scotia to Britain. That gave the signal for the British to remove the remaining Acadians from the peninsula and to invite some 2,000 families of British descent in the colonies of New England to leave their homes there to take the Acadians’ place. That done, the new settlers had hardly built their homes and set up their farms when the Thirteen Colonies to the south declared independence. At first, they were minded to join the Patriots, to the point where some called them ‘the Fourteenth Colony’. But during the Revolutionary War American privateers made such devastating raids on Nova Scotia ports that opinion swung decisively against the Patriot cause. Reluctantly, the New Planters, as they came to be called, decided to dig in and nurse their resentment against the British within the boundaries of allegiance to the Crown.

At that moment, the last thing they wanted was a straggling army of some thirty thousand Loyalist refugees arriving on their doorstep. They were vociferous in their objections to the point where there was a good deal of random and unprovoked violence – and even official persecution. The Loyalists, wrote Colonel Thomas Dundas, ‘have experienced every possible injury from the old inhabitants of Nova Scotia’.3 The upshot was that in 1784 the British had to intervene to create a new colony to accommodate those Loyalists who had found shelter on the Acadian mainland and who wished to leave behind the unhappy experience of the peninsula – and the abuse of the New Planters.

The new colony, it was decided, was to be called New Brunswick (the name was an anglicisation of the German city of Braunschweig, one of the ducal titles of King George III). Furthermore, the British Governor of Quebec, Lord Dorchester, announced that all those who had remained faithful to the Empire – and their descendants – were to be distinguished by the letters U. E. after their names, ‘alluding to their great principle The Unity of the Empire’.4 The Loyalist motto in turn duly became the motto of the new colony. Its imperial vocation was thus established at its birth.

New Brunswick is now one of Canada’s three Maritime Provinces, perched somewhat uneasily at the north-eastern corner of the American continent. To the north it is bounded by the Gaspé Peninsula of the province of Quebec and Chaleur Bay, to the east by the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and Northumberland Strait, to the south by the Bay of Fundy and to the west by the American state of Maine. Unlike its sister provinces, Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia, which are wholly or largely surrounded by water and hence climatically defined by the Atlantic, New Brunswick, although it has a long sea coast, is sheltered from the great ocean by its neighbour Nova Scotia, with the result that its climate, particularly in the interior, is to a large extent continental. The winters are cold to the marrow and the summers are hot, fierce and dry. Frozen rivers – its wide rivers and its spruce forests are the dominant characteristics of the province – make travel difficult in the dark months of the year and are given to flooding as the ice melts, bringing debris down from the hills and the logs which have been cut by the shivering woodsmen. Then it is the time for the Atlantic salmon, running in with the tide to make their way to spawn in the reeds in the source streams.

As is frequently the case in inhospitable climates, the weather and geography have determined both the spread and the activity of the population. In fact, the spread has hardly changed in the 200 years of the province’s history. Of a total population of 751,171 recorded in the census of 2011, a third were Francophone, living where their Acadian ancestors lived after being bundled out by the British. The central area around the river Miramichi provided a haven for the Scots of the Lowland diaspora of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and the Irish fleeing the potato famine of 1845. To the south lies the redoubt of the old Loyalists in the port of St John and the capital Fredericton over 100 kilometres to the north on the St John River. Today it has all the conveniences – and inconveniences – of modern life. One hundred and fifty years ago it was a ‘land for the huntsman, the fisherman, of lumber and saw-mills and possessed of a tiny coasting trade, and in the distant past a ship-building industry, where great ships were launched’. But for William Maxwell Aitken, the first Lord Beaverbrook, the land, the province, the New Brunswick of his childhood, had ‘always been home’. It was ‘the nursery rather than the career of prominent Canadians. It has indurated [sic] the brood and sent it forth to richer climes to conquer.’ For Beaverbrook, the induration, whatever that meant, was the legacy of Loyalism.5

In his later years, he may indeed have thought of New Brunswick as some sort of spiritual home. The extent of his benefactions, a library here, a university endowment there, carillons for churches, an art gallery with the most sumptuous works of European masters almost thrown in as a bonus, testify to his efforts to secure his reputation – even his immortality – in the province. Yet Max Aitken, as he was known until his elevation to the British peerage, left New Brunswick as soon as he could. As he wrote himself, he was one of the brood who went forth to richer climes to conquer.

This comes as no surprise. He had, after all, arrived there in the first place by a tortuous route. The Aitkens (the name was quite common in their original home) lived in the rolling countryside of West Lothian in Scotland. Max’s own grandfather was a man of substance – a tenant farmer on the estate of the Marquis of Linlithgow and a lime merchant with property in the market town of Bathgate. The main farm itself, known as Silvermine after the earlier silver workings which had subsequently given way to lime works before these too reached exhaustion, lay in the extreme corner of the parish of Linlithgow, abutting the parishes of Torphichen and Bathgate. In fact, it was at Torphichen that the Aitkens worshipped and where, at least from the middle of the eighteenth century, they were buried.

Torphichen itself is an attractive enough place of about five hundred inhabitants, with rows of miners’ houses running alongside steep and rather narrow roads. Situated some thirty kilometres west of Edinburgh, its main feature is the ruin of the Preceptory, or Headquarters, of the Knights Hospitaller of the Order of St John of Jerusalem. Built originally in the twelfth century, it was expanded over the years to include a cruciform church, living quarters and, to complete the complex, a hospital. Before the Reformation its history was colourful. William Wallace held his parliament here before the Battle of Falkirk in 1298 and after the battle King Edward I was brought to the hospital for treatment for an injury sustained when his horse unseated him and then, for good measure, trod on him. The Hospitallers then made the mistake of fighting on the English side at Bannockburn but were allowed to return to the Preceptory by Robert the Bruce. They were unable to survive the Reformation. In 1560 the Order was disbanded and the buildings, apart from the nave of the church which was used as a kirk, allowed to fall into disrepair. In the eighteenth century a new kirk, unfortunately of little architectural merit, was built around the ruins. Yet for all its history, today’s visitor finds it a tranquil, even sleepy, place.

Not far from Torphichen Church is the old parish school. Although it is not known precisely where he was born, it is almost certainly here that Max Aitken’s father, William Cuthbert Aitken, received his early education. The third child of ten, and the first son, he was enrolled at Bathgate Academy at the age of eight in 1842. He ‘matriculated at two shillings in the Rector’s Department’,6 a class reserved for the brighter pupils, and went on to study humanities at the University of Edinburgh. This was followed by a further four years of Divinity also at Edinburgh. By 1858 he was ready to be examined and received in the Presbytery of Linlithgow as a probationer to the Holy Ministry. That done, he was looking to a steady future in the domestic Church of Scotland. But there was a problem. In short, there was no job open to him. All the posts in the Presbytery of Linlithgow, and in the neighbouring ones, had their incumbents, all of them years away from retirement. Probationers had to occupy themselves as they might with casual preaching engagements and the odd hour of teaching. As far as money was concerned, there was no alternative for him but to live at home at Silvermine.

It was the schism in the Church of Scotland, known as the Disruption of 1843, that, indirectly, rescued William Aitken’s career and, in doing so, resulted in Canadian birth and nationality for his son. In May of that year the row which had simmered for some ten years over who had the right to appoint ministers of the church came to a head. Tradition and practice had it that the right to do so lay with the patron, normally the landowner of the district. Objectors held that this infringed the right of spiritual independence of the church, claiming the overriding ‘Crown right of the Redeemer’ as justification. As with most arguments of this sort, the dispute was conducted with a good deal of heat and very little Christian charity. The upshot was that about a third of the ministers walked out of a stormy meeting of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in St Andrew’s Church in Edinburgh to form the Free Church of Scotland.

St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, Maple, where Rev. William Aitken served as minister, c. 1908.

The schism, painful as it was, led to a number of results. The first was that the remaining majority in what liked to call itself the Established Church of Scotland became very much less rigorous in the application of Calvinism in the face of the vigour of the dogmatic assertions of its Free Church opponents. The position of saints, for instance, precarious since the Reformation after the thunder of Calvin himself and now subject to Free Church anathema, was covertly reinforced – new churches were named after the saints of old such as St Andrew, not least because it proved loyalty to Scotland’s patron saint and hence to the civil establishment. The doctrine of predestination, equally, started to be viewed with a good deal of caution. Yet whatever the theological wrangles, it was the undignified scramble for congregations that had the greatest effect on the ground. If ministers defected to the Free Church, it was only natural that they would try to take their congregations with them. If the congregation agreed, the money went with them, as well as, in all probability, the church building and the accompanying manse.

The effect was far reaching. Even in the North American colonies there were defections. The small lakeside town of Cobourg, for instance, in what was to become the Canadian province of Ontario, there was one such. True, Cobourg was essentially a Loyalist town – named after another Hanoverian title – but among the 3,500 residents recorded in the 1851 census there was a sizeable number of Scottish descent. In 1844, when the news of the Disruption reached them, the congregation, who had previously adhered to what they had thought to be the true faith, defected. It was obvious, so it was argued, that the right to appoint a minister must lie with the congregation and not with a civil patron – particularly one who might owe his right to some dim and distant British legacy. The minister and congregation switched their allegiance as one and took over both the church building and the manse. Uneasily, since they were not entirely clear about the theological divide, they declared themselves true followers of Presbyterian principles as set out by Calvin and his Scottish acolyte John Knox. All remained calm until 1859, when the official Church of Scotland took legal action against the Free Church to recover the church building. Judgment was given in its favour. Undismayed, the Free Church congregation simply built its own church. That done, the congregation sat back to await events.

By that time the dispute at Cobourg, together with all the parallel defections in other parts of the colony – and, indeed, in other colonies – had triggered alarms in Edinburgh. The Colonial Committee of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland had been forced into action. A trawl was made for candidates who might be willing to serve abroad. One of the names that came up was that of Mr William Aitken, an unemployed probationer in Linlithgow. At the same time a request was received in August 1862 from a Dr Barclay of the Presbytery of Toronto for ‘two or more missionaries [sic], one Gaelic speaking’.7

Given the nature of the request, the mills of the Colonial Committee ground at a remarkably slow pace. In March 1864 Dr Barclay was obliged to reiterate his request. This was laid on the table at a further meeting of the committee on 31 May but ‘consideration … was postponed until further information was received’.8 It was not until July that the decision was made. ‘The Rev William Aitken’, the minutes read, ‘was appointed to the charge of Cobourg, Toronto, with a salary of One hundred and fifty pounds a year for one year the circumstances of the congregation to be considered at the end of the first year of incumbency.’9 In other words, Aitken was given a year to sort Cobourg out.

It was not much of an offer but at least it was a job. The salary was, for the time, not ungenerous – worth some £13,000 in today’s values. In addition, he was to be paid £25 for clothing and £22 for the passage across the Atlantic. Yet in terms of job security it was about as precarious as could be. There was also one further hurdle. Aitken had yet to be ordained. This meant a return to Linlithgow Presbytery to complete his trial discourses and to undergo a question-and-answer session in Divinity and Church History. All that completed satisfactorily, he ‘received from the brethren the right hand of fellowship…’, listened to the Moderator of the Presbytery addressing to him ‘suitable admonitions as to his pastoral duties … signed the Confession of Faith and the Formula of the Church of Scotland’.10 He was now free to make his way, by himself, to a new home, a new job – and a new continent. In short, both in his own life and geographically he was going to a New World.

As it turned out, the whole venture was something of a fiasco. He made his way along the various stages of the laborious journey – the details are not recorded but at the time the preferred shipping route was from Glasgow to Liverpool, from there on the uncomfortable winter crossing of the Atlantic to Boston, on to Halifax, and then by land to Montreal and Toronto – to arrive in Cobourg before Christmas 1864. Once there, he found the congregation unrepentant, the manse dilapidated beyond possible occupation and the church of which he had by law acquired charge almost a ruin. His only recourse was to find lodgings, uncomfortable as they turned out to be, and summon his younger sister Ann to cross the Atlantic and join him in his lonely misfortune. This she dutifully did.

The stand-off could not last. Nor did it. Well before the completion of his one-year assignment, Aitken was thrown a lifeline. On 3 October 1865 the congregation of Vaughan, ‘desirous of promoting the glory of God and the good of the church, being destitute of a fixed pastor … have agreed to invite, call and entreat … you to undertake the office of Pastor among us and the charge of our souls…’11 Not only was the call a career lifeline but it came with pledges of financial support. At their meeting the previous June at which the elders of the congregation decided to make their call, no less than $115 in half-yearly payments to the management committee of the parish had been signed up. Furthermore, the elders and managers of the congregation promised that they and their successors would use their best efforts to raise $500 every year of Aitken’s incumbency in consideration of his services. Finally, they promised him the use of the manse and the glebe and held out the prospect of an increase in his stipend as might be suitable in the future. The call could not possibly be refused – and was duly accepted.

But there was a snag. Vaughan itself was little more than a small township on the fringe of the growing conurbation of Toronto. Straggling along the boundaries of a swamp, a road had been built in 1829 to encourage settlement to the north. In the course of time, the settlement developed into a community. The community then grew to the point where it became the seat of Vaughan’s – admittedly little – civil administration. With that came, naturally, given the nature of the community, the foundation and subsequent oversight of a church. William Aitken, having accepted – and been accepted for – the post of minister, now found himself in charge of a congregation rather smaller than the one he had left behind. Nevertheless, it existed – and the congregation had resisted the blandishments of the Free Church.

The main feature on the ground was the profusion of trees which lined its uneven streets. Disregarding the soft, feminine implications, the inhabitants had decided, after much discussion and renaming, to call their parish Maple in honour of the trees. This they were conveniently able to do since there had been little time for local tradition to take hold. Maple, and its sister village Nobleton, were indeed recent foundations. The two heads of the founding family, Joseph Noble and his elder brother Thomas, had been born in Strathblane, on the north-eastern fringe of County Tyrone, in what was a largely Catholic area. Without jobs or prospects, in their thirties they had taken the long voyage across the Atlantic and arrived in Toronto at some point in the 1830s. They bought land – marshy at best – just outside the Toronto boundary and still available under the Crown concession.

Thomas farmed the land and Joseph started a pub. The pub did so well that Joseph was not only granted the licence to be postmaster but was also able to buy additional land and start marketing the produce from his brother’s farm. Not content with that, in 1844 he married the daughter of a close neighbour, Sarah McQuarrie, whose family had migrated to New York from the Scottish island of Mull early in the century. On 19 July 1845, their first child – Jane, sometimes known as Jennie – was born. Two years later their first son – Arthur – joined her. They were not to know it, but both of them were to play their parts in the Aitken family story.

Maple was, as a community, modest but by no means impoverished. Along Kemble Street, rough as it was, the houses were well built of brick with steep tiled gables, upper rooms and chimneys to release the smoke from the wood burners heating the floors below. Sanitation, of course, was primitive – outdoors – and water had to be collected. Yet it was a friendly place and William and Ann soon settled down. The congregation, such as it was, ‘from 90 to 100 of us, chiefly from Scotland’,12 had in 1829 asked for permission to acquire a house in which they would be licensed to worship. That granted, they asked for a minister, who duly arrived in 1832. Ministers then came and went, but by 1865 the faithful had built both a proper church – named after the patron saint of Scotland, St Andrew – and a manse. It was this combination, apart from the relief of being free of Cobourg, which had attracted William to accept the call.

As it happened, romance – if it can be called that – was in the air. In 1866 Arthur, Joseph Noble’s eldest son, courted and then married William’s sister Ann. Soon afterwards, William solved the problem of his consequent loneliness by repeating the exercise with Arthur’s elder sister Jane. In truth, there was not much romance in either arrangement. In fact, of the two marriages, the second was by far the more successful. Arthur drank too much and was unfaithful to the point of contracting venereal disease, which he passed on to his wife and of which he died at an early age. So far, as it were, so bad. William and Jane in their turn settled down – but without obvious enthusiasm. There was little in the way of marital warmth. Jane ‘invariably spoke of her husband and to him as Mr Aitken’13 and William replied in kind. Yet in a formal sense, marital relations were productive. Six children were born in Maple; the last, seeing the light of day on 25 May 1879, was William Maxwell Aitken – soon to be known universally as ‘Max’.

By then William was getting restless, a situation that was exacerbated by the life of dissipation led by his brother-in-law Arthur, of which he, as a man of God, profoundly disapproved. Accordingly, when in April 1880 he received a call from the Presbytery of Miramichi in New Brunswick he was minded to respond favourably. After all, it was not just a matter of moving out of a difficult environment. The congregation of St James in Newcastle to which he was called was both well-endowed and had a thriving – mainly Scottish – membership. They certainly appeared eager to have him as their minister. When various candidates presented themselves for scrutiny he was given a particularly friendly reception and on 16 April the call was finalised. William, Jane and their young children prepared to move.

William Cuthbert Aitken must have appeared to his small children as resembling a particularly grim Old Testament prophet. Photographs of the time show him with a mass of facial hair – an unkempt white moustache and long white beard covering the whole of his lower face and collar – and above it a square, intransigent face with staring eyes below a square, intransigent forehead. His manner of life was equally daunting. His main – it seems almost his only – passion was a large library of books which were kept in a special room to which he would retire to smoke his pipe and ponder no doubt on the sins of the world. Discipline in his house was, as might be imagined, severe. On Sundays, the family was to show evidence of their ‘purity of heart’ by abstaining from anything which might give enjoyment or relaxation,14 and Monday was not much better since it was the day when Mrs Aitken did the washing and ironing – and the children were there to bring buckets of water as and when required. On other days there was little family joy. Meals were solemn affairs with prayers before and after eating. Occasionally, the father would indulge himself, after supper at six-thirty, by singing ‘without any grasp of tune’ some old Scottish folk songs.15 This sudden burst of warmth, of course, never occurred on a Saturday evening, when his mind was concentrated on the extended sermon exhorting the virtues of Calvinism which he was to deliver to the faithful the following morning.

Portrait of Rev. William Aitken, father of Max Aitken, c. 1880s.

Jane Aitken was no great beauty. Her face had the simian features that she passed on to her third son and although in her young days her figure was trim it soon filled out with the burden of carrying and bearing her many children. Her wardrobe reflected her upbringing and the position into which she married, as well as the social norms of the day: long black dresses with high white collars and white cuffs, simple black hats with white trimmings and, in winter, a heavy black fur coat and black muff. Like her husband, she was a disciplinarian. She may have been marginally more light-hearted than him, but her Ulster parentage did not allow much room for jollity – only for a shrewd and caustic gift of repartee. Her one affliction, which regularly struck when least expected, was asthma. The attacks were brutal, lasting hours and at times most of a day. When they occurred, ‘discipline was abandoned, and rules of conduct were relaxed’.16 Her daughter was called on to bake bread and biscuits, to do the washing and to clean the house. For the rest of the family, those times were both worrying and depressing.

Mrs William Aitken (Jane Noble), mother of Max Aitken, late 1800s.

The Aitken family, William, Jane and their six children (Sarah, nicknamed Rahno; Annie, known as Nan; Robert, the eldest son, who was known by his middle name Traven, after the Scottish farm over which the Aitkens had at times held a lease; Rebecca Catherine, known as Katie; Joseph Magnus, known as Mauns; and Max himself), left Maple in the spring of 1880 on the long trek to the north-east and to their new home in Newcastle. Max, aged eleven months, had, of course, no knowledge of the journey or of what had caused it. But without him knowing it, he was about to become what he was subsequently so proud of: a Brunswicker – or, as he would say himself, adding the extra spin, a New Brunswicker.

Notes

1 Motto of the Province of New Brunswick. The official (incorrect) translation is ‘Hope Restored’; a better rendition would be ‘He Restored Hope’.

2 Cited in Matthew Page Andrews, History of Maryland (New York: Doubleday, 1929), p. 284.

3 Cited in Samuel Delbert Clark, Movements of Political Protest in Canada 1640–1840 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1959), pp. 150–51.

4 Ibid.

5 Lord Beaverbrook, My Early Life (Fredericton: Brunswick Press, 1965), pp. 21–2, 27.

6 BBK/K/1/1.

7 National Library of Scotland, minutes of meeting of Church of Scotland Colonial Committee, 20 August 1862.

8 Ibid., minutes of meeting of Colonial Committee, 31 May 1864.

9 Ibid., minutes of meeting of Colonial Committee, 21 July 1864.

10 Extract from the records of the Presbytery of Linlithgow, meeting of 16 August 1864, BBK/K/1/1.

11 Call from the parish of Vaughan, Ontario, in the Presbytery of Toronto, 3 October 1865, ibid.

12 George Elmore Reaman, A History of Vaughan Township (Vaughan Township Historical Society, 1993), p. 144.

13My Early Life, p. 24.

14 Ibid., p. 38.

15 Ibid., p. 24.

16 Ibid., p. 72.

CHAPTER 2

MISCHIEF MAKER

‘A small, white faced little boy’1

‘The town of Newcastle’, according to one account, ‘might not impress the casual tourist.’2 Nowadays this goes without saying, since Newcastle, as a separate community with its own distinctive name, has ceased to exist. What was once an independent town is now no more than an annexe of the City of Miramichi, known prosaically and with hardly a nod to its past as Miramichi West. Moreover, regrettable as it may be, it is unlikely that any tourist, casual or otherwise, would put the suburb of Miramichi West high on his or her agenda for an uplifting cultural visit.

It was not ever thus. The account refers, of course, to the Newcastle of the nineteenth century and, even so, is perhaps unduly harsh. In 1880, when the Aitken family arrived, Newcastle had its own identity, and its own pride, as the shire town of what was then Northumberland County. There were, in addition to some elegant clapboard houses, a courthouse, local government offices, a railway station to serve the Intercolonial Railroad, a fine church and, to accompany them all, a newly built manse able to accommodate a large and intermittently noisy family. It was certainly a place of reasonable substance; a tourist, however casual, would have done well to take note and might, after all, have been impressed.

The town itself, in its prime, lay in a commanding position on a hill above the north bank of the Miramichi River. It overlooked the point just where the river runs downstream to the north-east in a wide bend out of the rough water which has made it unnavigable even in summer. The course of the river, and the guarantee in the warm months of a clear access to the sea, gave the site, and its accompanying port on the riverside, a ready advantage. To exploit it, in the late eighteenth century the Scottish forester William Davidson, along with a group of fellow Scots, settled the site and built a small river port. From that beginning Newcastle, as they called it, grew into a bustling centre for lumber exports, from there into shipbuilding and then, with the advent of steel-hulled ships, into the production and export of pulp and paper. As a spring or autumn sideline, of course, there was always the catch of the prolific Atlantic salmon.

Newcastle’s glory days, such as they were, did not last long. The lumber and pulp export trade fell off. Competition from the ports of Nova Scotia and New England, with ready access to the Atlantic all year round, proved too difficult to handle. Small wooden ships no longer found a market. In time, what was a thriving community in the early 1800s contracted steadily to the point where in the census of 1871 only some 1,500 residents were recorded in the town itself.

The decline in population was mirrored in the decline in church-going. Of the 1,500 declared souls, not more than 700 or so declared their religion as Presbyterian of one form or another. Of those, the Free Church, if the average of the period is applied, would have recruited half, leaving perhaps some 350 loyal to St James on the Hill. Proud they may have been and determined in signalling themselves in the 1871 census as Scottish, with or without the affiliation to the ‘established’ church, this was the somewhat meagre congregation to which the Reverend William Aitken was in 1880 invited to minister.

The Old Manse, Newcastle, New Brunswick c. 1950s.

The manse, the Aitkens’ new home, had only been built in the year before their arrival. In fact, they were its first occupants. It stood in the most salubrious part of Newcastle, surrounded by the houses of what passed for the gentility of the town. It was sufficiently spacious to provide a large family room on the ground floor while upstairs the bedrooms were large enough for two children to share; there was a study for William and a boudoir for Jane, attics for servants, two kitchens, a sizeable veranda in the front for fresh air when the weather was hot and a barn in the back for livestock. Furthermore, there were spare rooms available as the family continued to grow – Arthur was born in 1883, Jean (nicknamed ‘Gyp’) in 1885, Allan (‘Buster’ or ‘Bud’ according to preference) in 1887 and Laura in 1892. Tragically, one of Max’s elder sisters, Katie, was to die of diphtheria at the age of seven in 1881, shortly after the family settled in Newcastle.

It was, nevertheless, not the easiest house to manage. Commodious and comfortable as it may appear in description, there was in the days of Max’s childhood and adolescence no electricity, no running water, no indoor lavatory, lighting only by paraffin lamps and no heating other than wood fires in the main family room and in the minister’s study – with the consequent hazard of wood smoke and potential fire. (Yet, in the march of progress, as one of the most important buildings in the town it was among the first to have a telephone installed. Unfortunately, it turned out to be useless as there were no other subscribers.)

About five minutes’ walk from the manse stood the church of St James on the Hill, a fine, if for its purpose overlarge, example of colonial ecclesiastical architecture. It was regarded as a jewel by its congregation, who apparently volunteered in numbers to take turns for its maintenance. There was the normal, and in winter dreary, business of cleaning the church, sweeping away the results of the attendance, particularly in winter when boots brought in snow and mud, and preparation for the services. Special attention was needed to prepare the church for each event of the liturgical agenda: there was Morning Prayer on weekdays and Morning Service on Sundays, with Communion on the first Sunday of the month and at the major points of the Church’s calendar. For these there had to be perfect tidiness without undue and distracting decoration, as Calvinist custom and practice required. In the services themselves the family also lent a hand. Max’s job, much to his irritation, was to work the hand pump on the organ, which he did until, in a bout of inattention, he fell asleep at his post.

Max Aitken as a small boy of about ten years old, in a sailor suit, c. 1890.

All in all, apart from a certain rigour imposed by the father’s position, family life for the Aitkens in Newcastle was not much different to family life elsewhere. The children had regular fights, Max was bored from time to time and took refuge with various playmates in the neighbourhood, there were punishments for misbehaviour and rewards for virtue, childhood accidents – Max fell down one day and was nearly run over by a mowing machine – and, most important, there were the elements of childhood education of basic reading and writing taught at home by the parents, to make sure that the children were properly equipped before each in his or her turn started formal schooling. As the years went by, of course, the house gradually emptied, as each child went off to school and later to different careers.

In 1884, it was time for Max, at the age of five, to cross the threshold from home to formal education. As it happened, he was fortunate. The main school in Newcastle, affiliated to the church and named, perhaps rather portentously, Harkins Academy, was by all accounts a school of high standard. It was modelled on the Scottish pattern of primary and high schools, with a grading system as pupils advanced. Furthermore, it was comprehensive, accepting boys and girls from all sections of society (including illegitimate children); and it provided an education which was ‘wholesome, sound, non-religious and common to all’.3 In later life, Max was to claim that the education provided at Harkins ‘surpass[ed] that given at public schools (Eton, etc.) in England’.4 (As a matter of fact, he may well have been right, given the low academic reputation of English public schools of the day compared to their Scottish counterparts.)

Max Aitken’s class at Harkins Academy, Newcastle, New Brunswick, 1893. Max can be seen top left.

At his new school Max made what seems to be an almost comically bad start. A note dated 30 June 1885 from his primary school teacher records that in his first year he was present on only eleven and a half days out of a possible total of 156. This led to a caustic addendum by a senior teacher that ‘perhaps hooky was a compulsory subject in Grade 1 in 1885’.5 His performance was not much better as he moved up the grades and into the high school in 1890. According to the school records he was by a wide margin the worst offender for attendance in all his grades. Furthermore, he seemed wholly uninterested in the education on offer – apart from mathematics, at which he was surprisingly attentive. He was also recalcitrant to the point of rebellion. When his class was invited ‘to do such and such a problem in arithmetic or some other subject’, complained one teacher, ‘Max would promptly fold his arms, sit back and not raise his pencil’.6 ‘During his last year at the school he paid no attention whatever to any subject of the school. He sat in a little chair by himself up in front. He was placed there to prevent him from annoying the other pupils and distracting their attention from their work.’7

Max’s record as a pupil at school was bad enough, but worse still was his extracurricular activity. There were, to be sure, some harmless pranks, and a wayward career as a newspaper salesman and gossip writer for the St John Daily Sun, but it went well beyond that. He ‘organised parties to play tricks’ not only on the teachers but on ‘unpopular persons in the town’. (What his father thought of that is anybody’s guess.) He refined a device known as a ‘pin-trap’ so that it was invisible to anybody sitting down on the bench on which it was placed. ‘It proved very successful and was the means of shooting many a surprised boy screaming into the air. His victims were invariably the dull, more studious pupils…’8

Photo of young Max (seated bottom right) at the Sunday school picnic, on Beaubears Island, near Miramichi, New Brunswick, c. 1889–92.

If there was a redeeming feature it was in Max’s interest in English literature and the English language. True to his father’s love of books, he read avidly and, on the whole, with discretion – Walter Scott, Thackeray and Stevenson (but not, apparently, Dickens). His reading clearly helped him with the language since, at the age of sixteen, he produced a critique of Macaulay’s essay on Warren Hastings which took both the Principal and his father by surprise in its quality. But it was not enough to gain redemption with his father. William understandably disapproved of Max selling newspapers as a sideline, of his attempt to start an irreverent student newspaper and, after the school was burnt down in 1890, of his leading role in organising a protest of pupils at the unsatisfactory temporary conditions in which they were required to study. Indeed, by the time Max left school (without completing his course of studies), his father had ‘almost despaired of him’.9

But William Aitken persevered. Max’s ability in English and mathematics was enough to encourage his parents to send him, following the example of his elder brothers and sisters, to university. After much debate, the chosen destination was Dalhousie University in Halifax, where his brother Traven had studied law. It was not a happy choice. In fact, Dalhousie was lucky to be there at all. It had a history of financial trouble and by the time Max was sent there in 1895 to sit his entrance examination it was still far from final recovery. Founded as a college in 1818 by George Ramsay, Earl of Dalhousie and Lieutenant-Governor of Nova Scotia at the time, it was funded by the customs receipts collected (almost certainly illegally) after the British had captured the Maine port of Castine during the war of 1812 and operated it as a port of entry. When these funds ran out, the institution collapsed, to be re-founded in 1863 from local donations ‘with six professors and one tutor … in 1866 the student body consisted of 28 students working for degrees and 28 occasional students’.10 There was a further near collapse in 1879 until a New York publisher by the name of George Munro, from a Scottish Nova Scotia family, provided a lifeline. Thus rescued, the college managed to find its own building in 1886 on what is now Carleton campus.

In the event, Max arrived at this somewhat rickety institution in his most truculent mood. He sat through two days of the entrance examination complainingly but without too much difficulty. On the third day, however, he was required to sit a paper on Greek and Latin languages. In his own later account, he claimed that he was suddenly repelled by the whole exercise. ‘The paper was solemnly returned to the examiner with my declaration that a university career held no attractions as it involved unnecessary and even useless labour in futile educational pursuits.’11 Needless to say, he failed. But it was not just failure. He had offended the examiners and he had, specifically and intemperately, rebelled against his parents. But the truth is that, such was his mood at the time, he simply could not be bothered one way or the other.

His father again displayed all the virtues of Christian patience. After what was no doubt an embarrassing scene on Max’s return home to Newcastle, he suggested that a post as a clerk in the Bank of Nova Scotia could be arranged. The suggestion was met with blank refusal, followed by ‘passive resistance’, until the plan collapsed.12 It was a low point in Max’s adolescent rebellion, and his parents, obviously dismayed and upset, decided that there was little more they could do.

Max, in face of this clearly expressed parental disapproval, did what many rebellious adolescents do. He escaped from his home each morning to find life on the streets. But selling newspapers was no longer enough. It was too unreliable as a steady source of income. Almost as a last resort he took a job with a local pharmacist at a salary of one dollar a week. Although boring and menial, the job at least allowed him to gather gossip about the pharmacy’s customers, gossip which, in diluted form, he wrote up for the Daily Sun. Furthermore, while he was kept busy washing empty bottles he was able to reflect on the pharmacist’s profit and loss account. For the first time in his life he took an interest in the mechanics of business.

None of this, of course, added up to what Max wanted: an opening to a serious career which would take him away from a frustrating life at home in Newcastle. As luck would have it, however, it was when he was at his most frustrated and depressed that he was presented with just such an opportunity by the man who was to become one of the most influential role models in his young life.

Richard Bedford Bennett had been born in 1870 of a family of New Planters, originally from the state of Connecticut. He had grown up at his family’s small farm in Hopewell Cape, New Brunswick, had been educated locally and had studied law at Dalhousie, graduating in 1893. Taken on as an assistant by Lemuel J. Tweedie, a lawyer in Chatham, a settlement of a few thousand people on the opposite bank of the Miramichi to Newcastle, Tweedie soon recognised his ability and invited him to become a partner in his firm, to be renamed as Tweedie and Bennett. Bennett’s ability was undoubted. As a lawyer he was sharp, ruthless and to the point. As a person, however, he was not to everybody’s taste. He was a bachelor, a teetotaller, a strict Methodist, conservative in all senses of the word and a resolute British imperialist. He also had a fiery temper, was dismissive of those he thought inferior, frequently almost monosyllabic in conversation and intolerant of sin in any form. Unlikely as it seems, Max came to feel for him the calf love that only an adolescent boy can feel for an older man.

Bennett had first met Max when he was a teacher at a small school in Douglastown, a kilometre or so downriver from Newcastle. Although he was nearly ten years older than Max, the two seem to have struck up a friendship. Certainly, Bennett was much liked by Max’s parents and was a frequent guest to Sunday dinner at the manse. In the summer of 1895 Max came across Bennett on the Miramichi ferry. He told him about his troubles and asked whether he should take up the law as a career and, if so, whether he could join Tweedie and Bennett as an articled clerk. Bennett agreed to help his young friend and convinced his partner Tweedie to accept Max as a law student with duties as a clerk to pay his way.

There was, of course, a difficulty about money. Max was in the middle of negotiating an agency agreement to sell life insurance, as well as writing a column for the Sun, and he had also agreed to become a local correspondent for the Montreal Star. But the income all told hardly amounted to much. Always persuasive, he was able to borrow some money from a customer of the pharmacy, a lumberman by the name of Edward Sinclair. It was enough, if only just, to pay for lodgings and food in Chatham. At the age of sixteen, for the first time, he left home.

Contrary to Max’s expectations, the job at Tweedie and Bennett turned out to be suffocatingly boring. In fact, it was little more than typing a succession of legal documents. Max needed much more excitement than that and soon set about finding it. His first idea was nothing if not ingenious. He persuaded his friend H. E. Borradaile, a fellow guest at the hotel where he lived and a clerk at the Bank of Montreal next door, to use the bank’s writing paper (quite improperly) to write to the Chicago firm of Armour with a request to act as its agent for the sale of tinned meats and beans. No doubt encouraged by the respectability lent by the bank writing paper, Armour agreed. ‘Borradaile and Aitken’ was to be formed, but ‘when we came to discussing terms we were almost at once at loggerheads’ and the project fizzled out.13

More exciting was his excursion into local politics. In early 1896 Chatham was incorporated as an independent town. Elections to the town council were to follow. Max persuaded Bennett to put himself forward as a candidate for alderman and volunteered to run his campaign. This he did with great energy. There was much door-to-door canvassing, many leaflets sent out and, of course, promises of future performance freely made. It was only when Bennett was elected, by a narrow margin, that he found out that many of Max’s promises on his behalf were wholly reckless and could not possibly be redeemed. Bennett was furious – but Max was duly elated.

The elation did not last long. At the age of twenty-six Bennett was ambitious to move on with his career. Chatham was, after all, no more than a small local practice. The real business was to be found in the fast-developing west. Moreover, Tweedie was not an easy person to work with. When, in January 1897, Bennett was offered a partnership with Senator James Lougheed in Calgary he accepted without hesitation. Leaving Chatham and Tweedie was easy enough, but he did feel guilty about leaving Max behind, since he had a good idea what would happen to him without the protection of a senior figure in the firm. Max, it was true, had been an unsatisfactory apprentice, fooling around and apparently unable to concentrate to Tweedie’s satisfaction on the business at hand.

That was Tweedie’s main complaint. Max was still rebellious and bored. To quote just one example of his mood, in the days before Christmas 1896 he wrote to Bennett:

The office is very dull today, and an air of tranquillity rests on all the town. A disconsolate face and a ruffeted pink dress passed the window today. The lines on her face clearly showed that a young life had been blighted. I told her that it was better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all. Her only reply was a sigh. Fred Tweedie spent the morning in the office and not much work was done … This ink is frozen, this pen is bad, and this office is cold. As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be. Amen. Yours truly…14

In Adams House, where Max was staying, there was a back room at which he and others met to enjoy what they called ‘a gay time’.15 In other words, there was drinking, card playing and smoking. Tweedie – and Bennett, for that matter – was vocal in his disapproval. In return, Max refused to work overtime. ‘Mr Tweedie gets no free typing from me.’16

Bennett tried to persuade Max to try again to enrol in law school, but still without success. The suggestion was of little interest. Yet when Tweedie refused to promote him and offered his job to another aspiring apprentice, Max changed his mind. He walked out of his job and, for lack of an alternative, decided to have another try at a formal legal education. On the advice and recommendation of a friend of his father, a judge no less, he took the train to St John, found a place as an assistant in a law office – more typing of legal documents – and enrolled in St John Law School. But it turned out to be yet another mistake. After no more than a few weeks of boring work and loneliness in St John society, Max decided that he had had enough.

At just about the same time, Max’s father was pondering a reply to a letter he had received from Bennett soon after the latter’s arrival in Calgary. It reiterated the advice that he had given to Max, by then many times, that he should pursue a formal legal training. Confronted with what was a difficult choice for his son, William Aitken took his time to reply. After learning of Max’s experiences in St John, he sent a long letter to Bennett explaining why he could not accept the advice. Max had spoken to him about the matter, he wrote, and he had agreed to think about it. Hence the delay in his reply. ‘Would a College course be now a benefit to Max?’ was the question he asked. ‘My deliberate opinion is that it would not. His nature is such as would never make a first-class student. It is too eager to grasp the practical. And now that he has got a taste for business and the business intercourse of the world I believe that he could no more set himself down to a course of theoretical study’, the father concluded in a unexpected flight of fancy, ‘than he could take (or rather think of taking) a journey to the moon.’17

William’s judgement of his son proved, perhaps surprisingly, to the point. Max had already discovered a taste for selling whatever he had opportunity to sell, whether newspapers or life, accident or fire insurance. Yet he still believed that fortunes were to be made in the west. St John was not for him, so he decided to follow his hero Bennett and seek what he hoped would be his own fortune in Calgary. By the spring of 1898 he had sold enough insurance policies and written enough gossip for his newspapers that he had in his pocket the price of a train ticket for the long journey across continental Canada. Thus equipped, he set off west to Calgary.