Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Dolman Scott Publishers

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

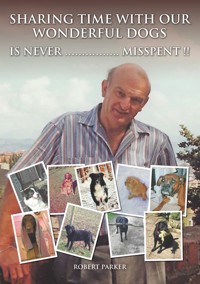

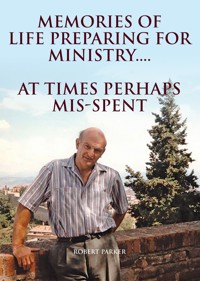

In what I write I wanted to try to share with the readers of my little book some of the events / happenings that had an impact on my life and contributed to my becoming the person that I am today. Besides that, in those early years there were a number of people who featured very strongly in my life. They were all wonderful people and I am keen that their lives are not forgotten. All our lives have ups and downs, and all our lives have those moments which become influential, even formative, on us as individuals. Moreover, most of us are able to reel off a whole host of amusing anecdotes. I include a few of mine here. I hope that you enjoy what you read

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 167

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Memories of amis-spent youth

Robert Parker

Published by Robert Parker 2021

Copyright © Robert Parker 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the copyright owner. Nor can it be circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without similar condition including this condition being imposed on a subsequent purchaser.

Dolman Scott Ltd

www.dolmanscott.co.uk

A little historical background

May I begin by saying a word about the photographs and illustrations that have been used throughout this book. They are NOT intended to illustrate the story that they are placed alongside, but more to give ‘a face’ to some of the players inside these stories, and then also to show their position within the wider family . Some members of the family shown in these photographs are not mentioned in the stories at all……. So perhaps I should mention that further books are both planned (indeed some are already partly written) in which many of them will feature in these future stories, and in which there will be a great many more photographs and illustrations. I also include a very much simplified family tree.

These stories are all set at a time either long forgotten by many of us, or not experienced at all by many others. I was born in 1943. It would be fifteen years before my parents had a car. To go on any long journey it nearly always had to be made by bus, and perhaps occasionally by train. Local short journeys were often on foot, and sometimes by bicycle. Every member of our family lived in a rented terrace house. No one could afford to own their own home. My earliest memory of Grandpa Tweedy and Grandma Pem’s house was of gas lights in all the rooms. I would watch with fascination as Tweedy would climb onto a chair by the gas light, strike a match, turn on the gas, try to set the gas mantle alight, and then curse as he pushed the match through the flimsy web of cotton, instantly destroying it, and then have to go to find a replacement. Yes, electricity was being brought into domestic properties, but as yet there was none in our homes. Cooking was done either on a gas-fired hob, or in an oven heated by the coal fire next to it. Baths were still taken in a metal bathtub placed next to the fire, with water carried in buckets from the kitchen. The streets were filled with many horse-drawn vehicles. Coal was delivered by horse and cart, and anything old but now not wanted and made of metal was collected by a rag and bone man, again with the scrap being put into in a horse-drawn cart, and with the owner walking alongside the horse. I wrote with either a pencil or a fountain pen; and to use the fountain pen, I filled the reservoir inside the pen with ink. Every pupil at school had an individual desk. Each wooden desk had a 10cm hole in the top called an inkwell, and into the inkwell was inserted a ceramic ink holder, a bit like an eggcup, but with straight sides, and which held the ink. Holidays were a great rarity. For most families, a couple of days each summer spent at the coast was a real treat, and those days were not with an overnight stay at the coast, but separate days, with the journey being made by charabanc (a bus… not a coach) going both there and back in the day. No TV! No computer or laptop! Films were only able to be seen by making a visit to the local cinema… when you could afford it. No fridge or freezer. Most homes had a pantry, built at a lower level than the rest of the ground-floor rooms, so that for most of the year food stored in this room stayed reasonably cool… But on a hot summer day, beware the smell!! Children played together outside most evenings and weekends with a group of friends. The games that we played were mostly football, cricket, cowboys and Indians, or hide and seek. When there was family leisure time at home, then until the age of about six or seven, we usually played such board games as Ludo, Snakes and Ladders, and thereafter migrated to Monopoly, and simple card games. Grandpa Tweedy taught me 5’s and 3’s, a game of dominoes that sharpened the mind mathematically! TV arrived when I was eleven, and it quickly began to replace family games times. For my parents’ social group, going to school beyond the age of 16 was uncommon. Going to university or college was unthinkable. Yes, we knew that some families were able to afford that; but for most, it was totally beyond their reach. By the time I was heading off to grammar school, all this was changing very quickly.

This was the world into which I was born and grew up as a child. As I write down these memories, I want to write a little bit about this world, and the impact it had on my childhood, but much more so about special moments during my growing up, and about those who influenced my life immensely, and helped fashion me into the person that I have become.

My mother and father, Bob and Greta (she was usually called Jane, because she didn’t like her given name!) were married in 1939, with Dad heading off immediately to be with his RAF unit, and only getting home very spasmodically. When I was born, he was serving in Aberdeen, and was then sent to Egypt, helping to fly supplies to Monty’s men, as the British Army tried to repel General Rommel’s troops in the desert. All through the war my mother lived at home with her parents in a tiny terraced house; although luckily, and surprisingly for the times, it had three bedrooms, and into which house I was born. My mother’s sister Clare, two years younger than Mum, also lived with them. She had a boyfriend named Peter, who lived at Shirebrook, some two miles away, and whom she eventually married. Peter was a regular visitor, and because my father was away, he became my surrogate father, spending hours playing with me, reading to me, and teaching me, first as a baby, and then through the first twelve years of my childhood. When I was born, my grandparents were all still alive, having lived through the First World War and survived. Tweedy and Pem, Mum’s parents and with whom we lived, had been born in 1894. Tweedy was the son of a farm labourer, but as soon as he left school at fourteen, went to work down the mine at the coal-face. Being down the mine, and in such difficult, dangerous and dirty conditions, the wage paid was so much better than that paid to farm workers. Pem, his wife-to-be, was the daughter of a publican who also owned quite a lot of property, and so her parents were relatively wealthy. They tried long and hard to persuade their daughter not to marry a farm labourer’s son. ‘He is beneath you,’ they told her – but love prevailed. Tweedy and Pem ran away and were married secretly. Her parents were absolutely furious. Pem was banned from the parental home for the rest of her life.

Grandpa Jack and Grandma Annie were both born in Leicestershire. Jack’s father was a farm labourer. Jack, like Tweedy, also deserted the land, and joined the Great Central Railway, finishing his career as Inspector in charge of Northern Division. Jack Parker was the second eldest of six brothers. The eldest, Robert, emigrated to Canada when he was just twenty years old, returning to England when he was 26. He came back to England because he had TB, and knew that he was dying. He lived the last few years of his life with Jack and Annie. When he knew that Annie was pregnant for the first time, he pleaded that if the child was a boy, they should call him Robert, after him. It was a boy, and the baby was named Robert. The child’s Uncle Robert died within a few months of the birth. Shortly afterwards, tragically, the baby Robert also died. When, a year later in 1918, Jack and Annie had another baby, again a boy, they again called him Robert. That second Robert was my father.

When my father came back from Egypt, everyone had expected him to go back to the coalmine and resume his work there. He had other ideas. The Government was appealing for men who, on returning from the war and had been discharged from the Forces, would go to be trained as teachers. My father applied, was accepted, and went to Ranskill College for two years. Ranskill was just ten miles from the home of Tweedy and Pem, and so he was able to come home on a regular basis. Then, as he qualified and got his first teaching job at Bolsover in Derbyshire, a miracle happened. My parents received a letter from the local council. On reading the letter, they whooped for joy. They were going to have their very own home. They were being allowed a council house only two miles away from my grandparents.

Throughout the early years of the lives of my grandparents and my parents, almost all road transport was horse-drawn. Railways were in their infancy. Homes had no bathroom, and the loo was usually in a shed somewhere in the garden. The ‘pot’ – the ‘bucket’ – in the loo was filled with water and chemicals, and twice a week a hole was dug in the vegetable plot and the contents emptied into it. The potatoes were often extremely large!!

Now the whole scene was changing. Motorised cars and buses were taking to the streets. The horse-drawn carts were seen less and less. Electric lights had become commonplace. Families could afford a whole week’s holiday at the seaside. Inside bathrooms with a loo were the norm in new-build houses, and a lot of older houses were having them built on!

For most people, for virtually all of their lives it had been a very difficult world… but it was rapidly changing.

NB. The final story that I have written comes some 40 years after all the others. It may seem out of place. All I can say is that I had no choice but to include it. It is so important to me, it has had a profound influence on all that I have come to know, feel and believe to be important about life.

Contents

A little historical background

Family Tree

‘Come and see my nother daddy’1946

The boating lake at Torquay1947

The flowers are better in the garden than in your vase1948

Falling through the shed window1948

Hetts Lane School… 1st love… then she vanished1948

The lamb chop1949

Why does George come every Sunday about 1pm…?1949

Robert does like his cakes…1949

Can I have some chips, please?1950

My very own garden… the first radishes1950

Why do you want to have another baby…?1950

Christmas Day at Warsop Vale1950

Go and meet Grandpa (Tweedy)1950

I’ll pay (Stags)1950

Building the tennis courts1950

I can get down the stairs in one jump…1951

The motor-bike to Bolsover1951

I hate cauliflower…1951

I’ll mend the clock… and there are two spare pieces1951

The carrots that died in the rows1951

Let me take you fishing1951

Little lamb, who made you?1951

It’s called progress1951

He’s for sale, missus1951

This is the most horrible cake I have ever eaten1951

Christmas Day at Warsop Vale… again1951

New Year’s Eve… blackened faces… why can’t I?1951

The lost shilling…1952

The winning run1952

The rabbit that changed colour1952

Wall cricket at Warsop Vale1952

I’ll take you to London1952

The footplate ride1952

Brent and Lyn getting knocked down1953

The second winning run1953

Scoring a goal at Welbeck1953

I will burn your eyes out1954

The first kiss… Dianne Dixon1954

No, he hasn’t passed1954

Bumps at Warsop church… you are in the choir now1954

Brunts School… fetching the sweets for a fee1954

F1 Fishing at Mablethorpe1954

Tweedy cleaning the shoes… the best chamois leather in the world1955

Pennies on the railway line1955

Getting the coal in1955

The choir trip to Mablethorpe…1955

Robert, I know what you’re doing…1955

Robert, be a good boy1956

Your grandfather is dead!!1956

Why can’t I be there?1956

‘If you can get to Monsal Head for the milk…’1957

Let’s pide his pie between us1957

It’s definitely gunpowder1959

Watch your Uncle Jack… he always heads to the loo1960

Hyde Park on a Sunday1960

F2 Robert, I love you2000

‘Come and see my nother daddy’

1946

Father smoking pipe

‘Daddy’s coming home today!!’

The whole house had been cleaned from top to bottom.

There was a bottle of champagne on the sideboard with four glasses, and a tray on the table, set with teapot, milk jug, sugar bowl, and four cups and saucers. Grandma had baked a fruit cake, and it had pride of place on a cake-stand in the middle of the table. ‘Daddy’ had been away for a long time. First to Scotland, and then to Egypt. He was in the RAF, but the war was ended. It was 1946, and he had been de-mobbed and was coming home!

I was three years old, and didn’t know whether to be excited or not. Mum had told me about Daddy coming back home over and over again, but we seemed to have managed okay when he was away. ‘He is coming home on the train to Nottingham, and then on the bus. He will be here very soon,’ Mum said.

Suddenly, there was a knock on the front door, in the other sitting room. ‘Robert, come with me’ Mum said. ‘Come and open the door and give your Daddy a hug and a kiss.’ Obediently, I got up, skipped across the room, went to the door, and opened it.

I was quite taken aback. Who was this tall, handsome man in such a smart uniform? And look at his shoes. How they shine. Before I could say or do anything, Mother rushed past me, flung her arms round his neck, and gave him a big, lingering kiss. Then he picked her up as if she was a feather and carried her inside.

Tea was made, and cake was cut. Champagne was opened and glasses filled. I sat quietly on this stranger’s knee, and kept looking at him quizzically. Then, for the next hour, there were smiles and tears, and a great deal of laughter. Grandma Pem and Tweedy seemed thrilled to see him, but Mum, without question, was ecstatic. Suddenly, I turned to him and said, ‘Come and see my nother Daddy.’ Then I took him by the hand, dragged him from the sofa, and pulled him towards the next room. The other faces in the room were horror-struck. What on earth was Robert going to do?

I led him through the sitting room door and took him to the piano.

‘Look,’ I said. ‘Look, this is my nother Daddy.’ I was pointing him towards his own picture sitting on top of the piano.

Mother had taken me into that room every day. She had held me in her arms in front of the piano, pointed at the picture, and said, ‘Robert, that is your Daddy’!!

The boating lake at Torquay

1947

Is there a problem? I wondered. Why have suitcases been brought downstairs and put by the kitchen door? I stood disconsolately by the kitchen sink and looked at the three cases standing there. The only time that I had seen a suitcase was when Dad had come home from the war. Was he going back?

Then Grandpa Harold appeared through the door to the stairs, and he was wearing his jacket. It’s only eight o’clock in the morning. He doesn’t usually go to the pub this early in the day, but he never wears a jacket to go anywhere else. But now my Mum and Dad have come downstairs, and Mum is wearing her smart coat, and Dad a jacket and tie. There must be something wrong. What can have happened?

‘Come on, Robert, let me put your coat on. We’re going on holiday. We are going to Torquay!!’ I thought that I knew what a holiday was: Mum had read me stories about people on holiday, and they seemed a good thing. ‘Yes,’ she added, ‘the sea at Torquay is beautiful. And there is a seafront with all the flower gardens. And there is a boating lake. We are going to buy you a yacht. A yacht is a lovely sailing boat!!’

I had never seen the sea, but only read stories about it. What an adventure it was going to be. I wondered if Torquay was as far away as Mansfield. It took a quarter of an hour on the bus to get to Mansfield!!

It took half an hour to get to Chesterfield railway station. Then all seven of us – me, Clare and Peter, Mum and Dad, Grandpa Tweedy and Grandma Pem, together with suitcases – hurried onto the platform to wait for the train. First, a London train came and went, with a great big red engine pulling at least ten carriages. It was quickly followed by our train. This time it was a black engine, but the train was just as long as the London one. I quickly discovered that Torquay was further than a quarter of an hour away. It was six hours later that we were getting off the train at the station at Torquay. I felt ravenous, even though Mum had taken a picnic to eat during the journey. As we walked through the station waiting room to the outside, Dad called a taxi. This was going to be another first. I had never been in a car before, let alone a taxi!! The driver jumped out and put two of our suitcases in the boot, and then strapped the third onto the roof. We all bundled inside. It hardly seemed worth it, because we had hardly got comfortable before we were there at the boarding house where we were to stay for a whole seven days. When my dad gave the driver two shillings and said ‘Keep the change,’ it did seem madness. The change might have bought me a couple of ice-creams!!

On the Monday morning, Dad took me down to the beach for a swim. Then, on the way home, he took me into a shop on the seafront and we bought my yacht. Well, actually he chose it and, of course, he paid for it. I would have preferred the large one with the two red sails, but the small one with the blue sail was lovely.

Tuesday afternoon and Dad suddenly announced that we were all going to go down to the boating lake and sail the new yacht, and then he added that, because afterwards we were going to go to a café for afternoon tea, we would all get dressed in our ‘finery’, as he put it. I looked very smart in neatly pressed short trousers, a fresh short-sleeved shirt, bow tie, and brand-new dark brown sandals.

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)