Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Huia Publishers

- Kategorie: Für Kinder und Jugendliche

- Sprache: Englisch

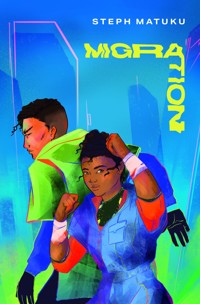

Farah of Untwa joins a school for training fighters, strategic thinkers and military personnel. It means she escapes her domineering mother and the tedious duties that come with being from a Ngāti in the upper echelons of society. But at the school, Farah, an intuitive, is teamed up with fighter Lase, a boy from a lower Ngāti. Farah's condescension and disturbing hallucinations and Lase's resentment test their partnership. But just when they finally seem to be working well together, the school is attacked by other-worldly forces. Farah and Lase must use their skills to fight the alien invaders and save their people from obliteration.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 406

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published in 2024 by Huia Publishers

39 Pipitea Street, PO Box 12280

Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand

www.huia.co.nz

ISBN 978-1-77550-713-0 (print)

ISBN 978-1-77550-888-5 (ebook)

Copyright © Steph Matuku 2024Cover image © Elsie Andrewes 2024

This book is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without the prior permission of the publisher.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

Published with the assistance of

Ebook conversion 2024 by meBooks.

FOR ANYONE WHO EVER WANTED TO BE SOMEWHERE FAR, FAR AWAY FROM HERE.

Leaves rustled as our people cautiously made their way down the bush-clad hill in the darkness. We waited for them in the valley below, beside the doorway we had created. It was an arc of swirling energy in greens, yellows, pinks and blues, the colours dissolving and reforming, coiling around each other like the iridescent shades of a pāua shell.

‘Come on, come on!’ Ishi was hopping from foot to foot in anticipation.

Next to him, Kaela leaned against a tree, arms wrapped tight around her belly. She inhaled, exhaled, her face taut, eyes closed. I hoped to hell that the baby would be alright.

His ear clamped against his walkie-talkie, Faraka was counting down: ‘Five, four …’

‘Yes …’ Ishi’s eyes sparkled and he looked as excited as if it was his birthday.

‘Three, two, one.’

An explosion ripped through the air, and a column of red fire from the distant camp snaked up, just discernible over the trees. There were muffled shouts and screams, and Ishi gave a whoop of jubilation.

‘I told you! The T’sen will be so busy sorting that out, they won’t have any idea half the camp has gone.’

‘Barracks Two almost down the hill; Three and Four on their way,’ said Faraka. He listened to the crackle of the walkie-talkie. ‘The guards are freaking out. They think we’re under attack.’

People began to emerge from the valley treeline. All were undernourished and dirty with tangled hair, and dressed in an assortment of clothing that just a few years ago would have been earmarked as rags. Some were carrying children. Others had meagre belongings tucked into thin grey blankets, and some had nothing at all.

One little girl was crying thick braying sobs that cut through the stillness of the night, resisting all her mother’s attempts to keep her quiet. Ishi handed her a crust he’d hoarded from his evening ration, and she immediately quietened, hurriedly stuffing the coarse bread in her mouth for fear someone would take it from her.

Erawa stepped forwards to greet them, leaning on the walking stick that Koru had polished and carved for her. She’d had to use it ever since one of the soldiers had broken her femur for being late for work detail. Erawa’s leg had never healed right, but she didn’t care. She’d always said that she was born for something better than dancing. She was right.

‘This is our chance,’ she said to the silent crowd assembling before her. ‘Our only chance to give our children a future worth living. I’ll be on the other side to welcome you home.’

Nobody clapped, but their faces lit up with hope. It was an emotion I hadn’t seen on anyone since the T’sen had arrived.

Erawa pushed the black hood back from my face and kissed me on the cheek. ‘You’ve done so, so well, Untah. You’ve saved us.’

‘We all did it. All six of us.’

‘But you found the way. Are you sure you don’t want to go through first?’

I laughed. ‘For the last time: you won the coin toss fair and square.’

She grinned. We all knew she’d cheated.

‘Just go,’ I said. ‘I’ll see you once everyone’s through.’

‘I’ll be waiting for you.’ Erawa waved at Ishi and Faraka, and blew Kaela a kiss. Then she stepped into the arc of swirling colours and vanished.

People lined up, quickly and easily – they’d had many years of practice trudging around the fields in pointless formation. One by one, they followed her through the colours.

The woman with the child gazed at the swirling mass of energy and then at me. ‘Will it work?’

‘I think so.’

‘Do you know what?’ Her smile was hesitant from disuse but still bright. ‘I don’t even care. Fuck the T’sen.’

She stepped into the energy mass. The colours swallowed her up.

‘Come on,’ said Ishi, urging those in line to go through faster. ‘We don’t have much time.’

‘How long will it last?’ asked Kaela. She sounded as though she was speaking through gritted teeth, and even though the night was cool, she had broken out into a sweat.

‘Ten minutes if it doesn’t conk out,’ I replied.

The doorway was still holding, the colours were strong and it hadn’t diminished in size at all, but I didn’t know how long that would last. How could I know? It was a measure of how desperate we were that the camp had bothered to go along with this mad experiment at all. If the T’sen caught us, we’d be dead. On the other hand, if we stayed we’d be dead too. The difference was that we didn’t want to die on their terms. It was as simple as that.

I bent to check on the machine that was supplying the energy to keep the doorway open. On top of the battered metal casing, Koru had drawn a picture of a bird encased in a hexagon: a sign that the six of us – Ishi, Kaela, Faraka, Koru, Erawa and I – were all going to fly away from here. I didn’t know how lucky his symbol would be, but the machine was still calibrated correctly, still humming along. Hopefully it would hold together long enough to get us though. Hopefully.

Faraka’s walkie-talkie crackled again, and he listened before reporting breathlessly, ‘Seven and Eight have been locked down.’

Ishi went pale. ‘No.’

Ishi’s mother and sister were in Barracks Eight. He glanced wildly up at the trees on the hill as though he was about to bolt, and I grabbed him.

‘They knew the risks. If you go up there, you’ll screw it up for everyone. They’ll understand.’

Ishi looked as though he was about to cry. ‘I’ll never see them again.’

‘You’ll never see them working like slaves, starving and dying,’ I told him. ‘Be glad of that.’

He nodded, and wiped a hand across his eyes before hugging me close. ‘I’m going to go through now.’

‘Yes. Erawa will need you.’

Ishi glanced over at Kaela, who had slumped back against the tree.

I shook my head. ‘She won’t come until Koru does.’

Ishi went to her anyway and spoke to her, urgent and low. Kaela shook her head and when he tried to urge her, she pushed him away. Gently, he took her by the arm and walked her slowly over to me.

‘You stay by me,’ I said to her, and she nodded.

‘I’ll see you soon.’ Ishi took the swirling colours at a running jump.

‘That’s Barracks Two gone, half of Three – and here comes Four now,’ reported Faraka.

Another explosion sounded, and everyone whipped their heads around. Another plume of fire lit up the sky, and there were more distant screams.

‘It’s too early; that’s not right,’ muttered Faraka. ‘What was that?’ he barked into the walkie-talkie. ‘Koru? Koru!’

Kaela snatched the walkie-talkie from him. ‘Sweetheart, please answer me.’ She spun towards me, her eyes wide and scared. ‘He’s not there.’

Faraka took back the walkie-talkie, tried again. ‘Koru?’

‘Hurry up!’ I roared, urging the people through faster: three, four at a time. Barracks Three was almost done: nearly a hundred people in just over seven minutes. I checked the countdown timer on the machine. Just six minutes to go. Faraka exchanged a look of resolve with me. If we were found out, we’d cut the machine off, destroy the doorway, be glad we’d helped at least a few escape … and then face our execution.

Kaela gave a gasp, and there was a splatter.

‘My water just broke.’ She looked scared but excited too.

‘Oh, Kaela,’ Faraka cried. ‘You have to go through.’

‘I want to wait for Koru.’

‘You have to do what’s right for you and the baby,’ I said. ‘Koru would kill us if you went into full labour here.’

‘But I can’t go without him!’ she cried, even as Faraka firmly led her to the doorway.

‘Take her through,’ he said to the young woman next in line. The woman nodded and took Kaela’s hand.

‘Come with me please, Faraka,’ Kaela pleaded.

‘I have to wait for Untah. I’ll see you soon. Go on. You’re holding everyone up.’

Kaela cast us one last glance, and then she and the young woman stepped into the void.

The walkie-talkie crackled and Faraka snatched it up. ‘Koru?’

He frowned, trying to make out the gabbling, and then his face became pale and set.

‘Do they know?’ I cried.

He nodded and beckoned at the line of people. ‘Come on!’

The urgency in his voice was unmistakable. Twenty, forty people, half of Barracks Four, went through at a run, and then a set of lights appeared at the top of the hill.

‘That’s not Five and Six?’

A clatter of gunfire from above, and a cluster of people just coming through the trees scattered, one crying out and clutching a bloodied arm.

‘Negative Five and Six,’ Faraka said. He was grabbing people and physically shoving them through now. ‘How many minutes?’

I blanched. I had been so caught up with Kaela and the ensuing chaos, I hadn’t checked. I bent to see the timer. ‘Forty seconds.’

‘Come on, come on!’ roared Faraka. There were fewer to come now; the line was almost done. The guns were still firing; divots of earth were popping up around us. Faraka pushed one woman through just as she was hit in the back. She fell through with a scream, the blood spray swallowed up by a rainbow of colour.

A familiar figure crashed out of the trees, sprinting hard towards us.

‘Koru! You made it! Twenty seconds!’ I shouted.

‘Did Kaela go through?’ Koru yelled.

‘Yes, hurry!’

Koru made to dive into the colours, but his foot caught on a loose clod of earth and he slipped, spinning sideways. The colours swirled around him but it seemed to take a long time before he eventually folded into the void and vanished.

‘Did he make it?’ Faraka asked.

‘I dunno.’ I checked the digital readout, my heart hammering in my chest. ‘Eight seconds.’

The T’Sen soldiers had broken through the tree line and were running towards us, their faces ghostly pale, their dark brown uniforms barely discernible against the night. They were waving guns, yelling at us to get down.

‘Seven, six …’

The last two people in line went through, and then there was just me and Faraka.

‘Five, four …’

Faraka grabbed my hand and for a moment we stood there in front of the doorway, the colours so enticing, so seductive that the shouts of the soldiers were nothing but meaningless background noise.

‘Three, two …’

We grinned at each other and stepped forwards, bullets spraying like hail around us.

‘One.’

And we were gone.

Farah was itching to escape, but her māmā’s iron grip made it impossible.

‘Everything depends on this,’ she was saying in a voice of such urgency that anyone but Farah would have thought it was the first time she’d said it. For Farah however, it was the same speech she’d heard a thousand times before. ‘Don’t let us down.’

Please, Farah thought desperately.Justletmego.It’smytime now. She didn’t say that out loud though. Instead she said dutifully, ‘Yes, Māmā,’ while trying to ignore the gold-dusted fingernails digging into her chin. She kept herself as motionless as she could. Māmā wasn’t above slapping her face in public if she thought she wasn’t being shown proper respect.

Māmā gave Farah a little shake before releasing her, and Farah backed away a couple of steps – a couple more steps towards freedom. But still Māmā talked on, looking at Farah as though she was searching for something. Obedience, probably. Humility. Deference. All those good-little-girl attributes that had worn thin over time and had finally vanished altogether. Farah could still act the part, though. She’d been doing it for months.

She tuned her māmā’s monologue out and kept her gaze at her feet as strangers streamed around them without a glance, the citizens of Aowhetū all jumbled up together at the Nilo Shuttle Station in one seething, stinking mass of humanity.

Dark-skinned women in expensive, floating robes elbowed their way past taciturn, sunburned workers from the south. Muscled city guards in red uniforms blatantly ogled a group of beautiful amber-eyed women who were dangling stringed instruments from languid fingers while, nearby, a tall man in a jewelled headdress loudly berated an elderly house-worker, whose grizzled head was bent in apology. Licensed hawkers cried out to passing customers to buy their keepsakes and refreshments. Temple acolytes drifted past, trails of glittering sparks falling from their long, painted fingernails, decorated masks hiding their true features. And every now and then Farah caught a glimpse of someone dressed like her, in the slim-line uniform that identified a wānanga trainee.

Finally, when the lecture trailed off into a disapproving silence, she gave Māmā a courteous bow of farewell, and watched as she and her ever-present entourage of maids, guards and advisers disappeared into the crowds. Farah felt a smile creep across her face and then she was off in the opposite direction, away from her ngāti, away from her māmā’s incessant demands, away from all of it, and good riddance too.

The first thing she did was yank at the beads Māmā had insisted she wear in her hair.

Jewellery was against military regs, but Māmā didn’t care about that. She just wanted Farah to look pretty, although Farah knew she wasn’t especially attractive – merely interesting looking on a good day. One beaded strand was knotted and refused to slide free, and Farah had to stop, dropping her kete at her feet and using both hands to untangle the beads from her plait.

Something sharp jabbed her in the back and she stumbled forwards, flailing for balance but ending up face down on the polished floor tiles. There was a shout and running footsteps and by the time she’d got herself together, her kete had vanished.

She scrambled up and looked wildly around but couldn’t see anything for the crowds around her. A middle-aged man with a bare chest and woven sarong hurried past and she grabbed at him, too upset that she had lost her kete with everything she owned in it to care that he wasn’t exactly her type of people.

‘Help me, someone’s taken my …’

To her astonishment, he just shook her off and continued on. But of course: she wasn’t wearing the trappings of an upper ngāti. She didn’t even have an expensive strand of beads to show off – she’d dropped them, and they’d vanished too. She was in uniform. She could be anybody. The realisation should have been liberating, but instead she felt helpless.

‘Please,’ she said to someone else, but they ignored her. She gazed around again, hoping to see the red uniform of a city guard, but there was nothing.

Whump! Her kete landed at her feet, and a male face came close to her own. Too bloody close. Reflexively, she thrust out a clenched fist, and he swayed back easily, as though he was dancing. Her swing went wide, putting her off balance, and she almost hit the floor a second time.

‘Pick it up,’ he said, sounding almost amused.

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘Pick. It. Up. You leave it for two seconds around here, and it’s going to get lifted. Again.’

He was wearing a uniform that was identical to hers, the dark blue contrasting exceptionally well with his untidy brown hair and eyes that were so dark they were almost black. Farah had to admit he would have been good looking if he hadn’t been so dishevelled. Then she saw the tail end of a silver tattoo snaking up the side of his neck, and she took a step back. So he was of the Hole! Well, that explained everything.

She crouched and, keeping a wary eye on him, rifled inside the kete, breathing a sigh of relief as her fingers closed over the slick laminate of her boarding pass.

‘How dare you touch my things!’ she hissed, drawing herself up and hoisting the kete over her shoulder. ‘Were you trying to teach me a lesson or something? Showing a girl from an upper ngāti how to survive in the big bad world?’

Now it was his turn to look startled. ‘What?’

‘Don’t “what” me. I’ve a good mind to call for a guard.’

His eyes narrowed and his lip curled. ‘I was only trying to help. Next time, I won’t bother.’ He stepped back into the sifting sea of people and disappeared.

Farah stared after him, outraged, and then went back to digging in her kete. It looked as though everything was still there, but the hair beads were definitely gone – something else for her māmā to nag about.

There was a touch on her arm and she flinched back, protectively tightening her grip on her kete. It was a girl, another trainee. There was a stocky boy next to her. The girl raised her hands in mock surrender and shook her head, her short brown curls bouncing.

‘Calm down! No agro here, I swear. You okay?’

Farah’s heart was still banging hard in her chest, and she had an uncomfortable feeling she looked a mess with her hair all over the place, but she forced a smile and said, ‘Yeah, thanks.’

‘I’m Janalel of Perinswa, combatant, and this is my brother Pascin. He’s an intuitive.’

Pascin proffered a hand, and Farah politely brushed her fingertips against his. Brother and sister were very similar looking, with curly hair and an open friendliness about them that she found a little disconcerting. People of her own ngāti took pride in staying aloof. ‘The sun has no affection for you, but it shines on you just the same’ was an old proverb inscribed over the gate leading to their lands. That said it all, really.

‘I’m Farah of Untwa,’ Farah said. ‘Intuitive.’

A flicker of a glance passed between Pascin and Janalel, and after a pause Janalel said, ‘Come on, the wānanga shuttle’s leaving soon.’

She moved off with her brother. They both seemed to take it for granted that Farah wanted to go with them, and after a moment’s hesitation, she did. They hurried down the crowded platform together, clapping their hands to their ears every time a shuttle rose or docked with a loud hiss of jets.

Although Janalel had politely left the question unasked, Pascin felt no such compunction.

‘So if you’re of Untwa, how come you’re slumming it at the wānanga?’

Farah hadn’t prepared an answer, and wished she had. She could bet she was going to get asked the same thing a lot.

‘Just looking for adventure,’ she replied, and immediately wished she had come up with something else. Looking for adventure? She sounded like a kid in a fairytale. Still, it was better than the complicated truth.

Janalel laughed. ‘I’d say you’d found a bit of adventure already.’

‘How do you mean?’

They turned into the shuttle bay. It was already packed with trainees clutching their kete and shifting from foot to foot in nervous anticipation. In contrast, the tall guy of the Hole stood at the back of the group, as motionless as a yang-cat, a ragged kete over his shoulder.

Janalel jerked her head sideways at him and whispered, ‘The way he took down that little rat-gasher? I swear, the kid only had your kete for about thirty seconds before he got nailed. He must have thought he got hit by a meteor.’

Farah blinked. ‘Are you saying that person from the Hole – I mean, Holitarn – got my kete back from a thief?’

‘What did you think?’

Ithoughthe’dstolenmythingsandthenbroughtthembacktoteachmealesson? Even in her own head it sounded stupid.

‘I wasn’t sure,’ she faltered. ‘It all happened so fast.’

The roof panels slid open with a wrenching, grinding noise, and then the thunderous whoosh of the shuttle rebounded around the bay as the transport lowered into docking position. The doors slid open and everyone piled in, rushing to get decent seats.

Janalel slung her kete under a free capsule and winked. ‘Yup. He doesn’t just look like a hero.’

Farah dropped into a capsule next to Janalel, the safety belts automatically snaking across her lap and shoulders. She tugged at them to check they were tight, glad to hide cheeks flushed with an unexpected feeling of shame. It wasn’t exactly a great start to her training as an intuitive. She had a sudden overwhelming urge to just grab her kete and get off the shuttle altogether, but then the doors slid shut, the thrusters engaged and it was far too late to change her mind.

The flight from the capital to the wānanga took nearly three hours, and because she was in a middle row of capsules, Farah could only just make out glimpses of scenery through the windows as they shot over the city and then the outer towns and various provinces. Three hours staring at the back of the seat in front of her wasn’t exactly scintillating, but Janalel made up for the lack of view. Farah learned a lot about Janalel and, by default, Pascin in that time.

She’d only vaguely heard of their ngāti before. Perinswa was military-aligned, and for the Perinswa kids, training at the wānanga wasn’t so much a choice as an expectation. Farah couldn’t say the same. No one from her ngāti had been selected to go to the wānanga in forever. Her people were more about competing with and defeating other ngāti through trade and finance – not fighting.

The wānanga lay on the coast. Farah had visited most of the country’s biggest cities but had never been this far west before. The sun sank directly ahead, sending red beams through the craft and making her feel slightly queasy.

She moved her head, trying to avoid a shaft of light in her eyes. Between the capsules, she caught sight of the tattooed guy sitting a few rows ahead. He gazed out the window, a tiny grin lurking at the corner of his mouth. As if feeling Farah’s eyes on him, he turned, and she immediately jerked back, pretending to study her nails.

A robotic female voice came over the intercom: ‘Destination in two minutes. Please prepare for touchdown.’

Janalel leaned back in her capsule, tightening the straps at her shoulders. ‘I’m so hungry. I only had a piece of fruit this morning, I was that nervous.’

Farah was nervous too, but she was working hard not to show it. If there was one thing she’d learned in trading negotiations, it was to never show weakness, or you’d get screwed. A bright smile and confident demeanour was a great cover for insecurity and fear.

Right now, her smile was so wide it was making her jaw ache.

The shuttle slowed as they flew over open green fields towards a solitary tower, the white stone tinted a rosy pink in the afternoon sunlight. The shuttle came to a stop directly over it before slowly descending. The brake jets engaged with a hiss, and the shuttle wobbled as it finally settled into the docking bay.

‘Welcome to the Western Wānanga. Please disembark.’

Seatbelts clicked and everyone grabbed their kete. The doors slid open to reveal a man on the platform. He was fiftyish, with short hair and a vicious knotted scar that encircled one dark eye before dropping down his cheek to his jaw. Six gold rings, representing the classes of the wānanga, were embossed on each shoulder of his black uniform. A silent group of twenty or so trainees was already waiting behind him.

The trainees getting off the shuttle came to an abrupt halt, and Janalel and Farah were shoved into their backs by the trainees behind them. The man regarded the milling, stumbling group with narrowed eyes and, without any change of expression, said, ‘Welcome.’

It was the most unwelcoming welcome Farah had ever heard.

‘Sixth class trainees,’ he continued, his scar twitching as he spoke, looking like a thin rika about to stick venomous fangs into his mouth. ‘This is your home for the next two years. Unless you drop out. Or die.’

There was a nervous laugh from the back of the group that faded off into a cough and then silence.

‘I’m Captain Riodan. You will call me Sir. Well?’

‘Yes, sir,’ mumbled a few tentative voices.

Captain Riodan rolled his eyes and cranked an impatient arm. ‘Get a move on before I send you all back again.’

The trainees, about thirty in all, shuffled out to join the others, who had presumably arrived on an earlier shuttle, and they all followed the captain off the platform and through a door leading out to the open roof.

The breeze whipped past, bringing the wild scent of the ocean. To the north lay dark green forests and pale green fields, spread out like a rumpled sleep-cover. To the south, a river coiled across a plain, and far to the east, the tall peaks and spires of the city of Venning glittered. A domed building rose a few paddocks over. This was the legendary Western Wānanga, one of five wānanga responsible for the initial training of Aowhetū’s best fighters, strategic thinkers and military personnel.

Farah, like everyone else, was gazing around wide-eyed, but Captain Riodan didn’t give them a chance to enjoy the view.

‘The only way off this building is down. Good luck.’

And he stepped off the side of the building.

Most of the trainees rushed over to watch as the captain plummeted down, down … and at the last possible moment activated a parachute that arrested his fall. As he dropped lightly to the ground, it folded up and slid back into his belt. Without looking back, the captain got into a small transport and headed off towards the wānanga.

There was a stunned silence. ‘Anyone remember to pack a ‘chute?’ Janalel called. There was a chorus of ‘No’s and some scattered laughter.

Pascin elbowed his way to the edge, peering down to the ground. ‘It’s, what, fifteen floors high? We definitely can’t jump.’

An attractive girl with long silky hair clapped her hands sarcastically: once, twice. ‘No kidding. I think we already worked that out. But thanks for the lesson in common sense.’

Her uniform was the same as that of the rest of the trainees, but the workmanship of the stitching and the quality of fabric was the equal of Farah’s and markedly better than everyone else’s. On most of the trainees, the new uniform looked a bit too stiff and crisp. On this girl, it looked designed, flawless – a second skin.

Farah glanced at her and then took a second look, recognition causing a chill to crawl down her back. If she wasn’t mistaken, that was Tari of Alendale, and her father was the leader of the Political Forum. Tari’s family and their latest trading policies were half the reason Farah’s ngāti was about to go bust.

Pascin blushed, and Janalel opened her mouth to defend her brother when a familiar voice broke in.

‘Any ideas, intuitives?’

All heads turned. It was the guy from the Hole.

Tari smiled at him, coiling a long loop of shiny hair through her fingers. ‘I’m an intuitive. I’ve got plenty of ideas.’

Janalel gave Farah a dig in her side with an elbow and made a gagging gesture with a finger down her throat. Farah couldn’t help giggling.

The guy from the Hole glared at her. ‘Do you have anything positive to contribute, or is this whole thing just a big joke to you? Because I don’t know about you, but I’m starving and I kinda want to get off this Gods-damned roof.’

Farah felt her mouth drop and she quickly snapped it shut again. In all her life, nobody had ever spoken to her like that before – especially not anyone from a lower ngāti like the Hole. Tari tittered, raising innocent eyebrows when Farah shot her a murderous look.

‘We could tie our gear together – make a rope,’ Janalel said quickly.

‘Has anyone checked the door?’ suggested a tall boy with a head bristling with short black plaits, and broke away to do just that. He returned within moments, crestfallen.

The group broke into loud chatter, Tari’s imperious tones declaring loudly over the rest, ‘There’s no way you’re using my clothes, they’ll get stretched!’

Farah moved to the back of the group and then away to the other side of the building, fuming. So she’d made a mistake back at the shuttle station. She’d apologise … eventually. But there was no need for him to be so rude, singling her out like that in front of the whole group. Who did he think he was?

The view almost made up for her irritation. The coastal cliffs stretched away in both directions, a line of frothy white surf separating the blue ocean from the pink sands of the beach. The breeze brought the sharp scent of salt. The constant movement of the waves below made her feel restless. She was a long way from the placid green gardens of Ngāti Untwa, where the air was always scented with perfume and the birdsong was melodic and sweet. This place hummed with energy. She could actually feel it. It was like a soft vibration coming up through the floor beneath her feet.

She frowned, and stepped sideways to the left. The vibration stopped. She stepped back and felt it again: a faint prickling, coming right through her boots. She took a sideways step right and then another, and the strange sensation abruptly ceased. She moved back to where she’d felt it most strongly, and took two steps forwards. The prickling didn’t abate, and she closed her eyes, concentrating. She took a step forwards – and another and another.

A girl squealed, ‘Look out!’

Farah’s eyes flew open and she gasped, swaying. She was standing in midair, a couple of paces away from the building. She could see the ground far, far below, and it was only the vibration under her feet that provided any sense of solidity.

The rest of the group hovered at the edge of the building, and Pascin gave a shout.

‘I can feel it! Over here.’

Janalel moved to his side. ‘I can’t feel anything.’

‘And that, Jan, is why you’re not an intuitive.’

Pascin tapped his feet from side to side, echoing Farah’s movements just moments before, and motioned to Janalel to grab him around the waist.

‘It’s very subtle.’ Pascin stepped confidently off the edge of the building, ignoring Janalel’s moan of trepidation. ‘Usually solid necrian energy displays some kind of opalescent colouring, but this is completely invisible. Fascinating.’

Janalel took a shrinking step and then another.

‘This is not my favourite,’ she said faintly.

‘Go on,’ Pascin said, motioning to Farah. ‘What are you waiting for?’

The other trainees quickly formed a line and stepped out after them. Farah shuffled forwards, closing her eyes. It was easier to focus on the vibration if she kept her eyes shut, preventing her brain from going into cataclysmic vertigo.

The invisible path angled down and around in a corkscrew spiral. It seemed a long time before they finally reached the bottom.

Farah stepped down onto the grass with a sigh of relief. Her legs were a bit wobbly. The guy from the Hole came around from the side of the building and looked at her in surprise, rubbing his hands together. Farah could see they were reddened at the fingertips. Had he actually managed to climb down the tower itself? She looked closely at the wall. Faint little notches had been carved into the bricks.

By now the other trainees were down on the lawn, curiously staring at him too, but then Pascin turned to Farah and started clapping. Several joined in.

‘Don’t,’ Farah said, covering up her discomfort with that practised jaw-breaking smile. ‘Someone would have sorted it sooner or later.’

‘I would have bet on much, much later.’

A young woman in a green uniform stood by a door in the base of the tower, a portable viz-screen in her hand. When the door slid closed, the edges seamlessly met the wall, essentially camouflaging it.

‘Some of our trainee teams have been up there for days,’ she continued. ‘Some died.’ She didn’t look sorry. In fact, she looked positively cheerful. ‘I’m a mentor: Lieutenant Alma of Darinshead. And you?’ She pointed at Farah. ‘Where are you of?’

‘I’m of Untwa, Lieutenant. I’m Farah.’

There was a ripple of interest among those who cared – those of Untwa were renowned as leaders in textiles and fashion. In her peripheral vision, Farah saw Tari widen her eyes and then look away.

The lieutenant nodded, and tapped on her screen. ‘Well done. You’ve just earned yourself fifty xin.’

‘Wait,’ Farah began, shooting the guy from the Hole a quick glance.

‘It’s not just about who’s first,’ the lieutenant said, correctly guessing what Farah was about to say. ‘It’s about teamwork. You might want to work on that, Lase.’

The guy from the Hole stared blandly back at her, as if he couldn’t care less.

‘Right. Quick march over to the wānanga and you can find your sleep-spaces and partners. Combatants have been partnered with intuitives depending on test scores and moral values and brain compatibility and … oh, a lot of things I can’t be bothered talking about now.’

She strode through the group and led the way along a dirt track almost covered over by tufts of grass. Swarms of white tarina buzzed around the wildflowers in the paddocks, and Farah had to watch where she walked lest she was stung.

Janalel fell into step with her. ‘You did really well.’

‘It was a fluke,’ Farah said, honestly. ‘I was looking at the ocean. You don’t see that so much back home.’

As they drew closer to the white domed building of the main wānanga, the untamed fields gave way to landscaped gardens dotted with carved statues and fountains, and the dirt track became a smooth paved path. Little side paths disappeared into groves of dasr trees and around sloping hills.

Farah’s Untwa ancestors had invented a blue fabric dye made from plants that only grew on the hillsides surrounding their homes. The same subtle toning coloured the decorated paving stones under Farah’s feet, and the familiar hue had a surprising effect on her, both electrifying and calming at the same time. As she stepped under the entrance archway, she felt as though she’d left the old Farah behind, and a new Farah, one to be reckoned with, had finally arrived.

The manicured gardens, tinkling fountains and exotic flower beds had reminded Farah of Untwa, but the similarities vanished once she was inside the wānanga warren. The building was purely utilitarian, with white walls and clean surfaces: everything was designed for purpose, not pleasure.

Farah and the other trainees walked down the curving corridor, their voices hushed and their soft shoes padding lightly against the tiles. Every now and then older trainees passed them, one twirling a jad-stick, another with a hand clamped to a bleeding gash on her shoulder. A small group jogged by, sweat dripping down their red faces. They looked as though they had been running for hours.

‘The wānanga is built in a spiral,’ the lieutenant called back to them. ‘You sixth classes only have clearance for the outer layers. Your wristbands will let you through the doors. If you can’t get in, you don’t belong there.’

She halted at a junction and peered at her viz-screen. ‘Right. Sleep-spaces are down these two corridors. As I said before, your test scores have designated who your partner will be. You’ll retain your partnership right through to second class. You will eat with your partner, sleep in the same space as your partner, train with your partner …’

‘What if you don’t like your partner?’ interrupted a boy with sandy brown hair and a cheeky smile.

‘Golan of Barrad, is it?’

The boy nodded.

‘Compatibility and personal preferences have been taken into account. Many of you may have already been drawn to someone else in the class because of the similarities in the way your minds work. All partnerships have some kind of common ground on which to forge a friendship. And don’t interrupt me again.’

Golan looked abashed, and the lieutenant began reading out the partnerships and directing them to their rooms.

‘Farah and Janalel,’ she called over the chatter as the trainees found their partners and left to find their quarters.

Janalel grinned at Farah. ‘Nice work, partner.’

Farah smiled back, relieved to find that she wasn’t going to be partnered with Tari or Lase, the only other two in the class she felt drawn to – if only by animosity. The two girls left Pascin and the remaining trainees and followed the lieutenant’s directions to their sleep-space.

It wasn’t much more than a cubicle with two workbenches, a viz-screen, two sleep platforms, and two racks to hang their spare uniforms on. It was a world away from Farah’s comfortable rooms at Untwa, but she wasn’t complaining. After all the luxury and excess of her old life, the prospect of owning very little was liberating. The lack of clutter seemed to free up her mind, making her more alert to her surroundings.

They unpacked their meagre belongings, Janalel keeping up a steady stream of conversation and not seeming to mind that Farah wasn’t so forthcoming.

‘Pascin tested ninety-four as an intuitive, which is the highest score our family has had in, like, ever,’ Janalel said proudly. She’d recorded ninety as a combatant, which was good but not as good as she had been hoping to get. ‘It was my instincts and reflexes that let me down.’ She plopped down onto her sleep platform and grimaced at the lack of give in the thin mattress. ‘My mind wanders a lot. Still, I can work on that. My speed and strength are pretty good.’

She flexed an arm to show a taut, sinewy bicep.

‘If I’m doing my job properly, that shouldn’t be much of a problem,’ Farah said. ‘Hopefully I can get you those extra seconds you need.’

Janalel brightened. ‘You’re right. I can’t believe you got a ninety-eight! I’ve never heard of a score that high before. You must have known you were an intuitive right from when you were a baby.’

Farah felt a warmth spread across her cheeks and she ducked her head, disconcerted. It was the first time she’d been praised for the score that had given her automatic entry into the wānanga. When she’d told her parents, her pāpā hadn’t spoken to her for a week and her māmā had thrown things. Lots of things.

Although anyone could be born with a talent for intuition or combat, only a few made the choice to develop it at a wānanga, and even fewer were accepted. Most intuitives and combatants were military-aligned by ngāti. The others tended to be of middle and lower ngāti keen to make a name for themselves and bolster their ngāti’s prestige. Generally speaking, people of Farah’s privilege preferred to stay home.

‘Well, with my ninety and your ninety-eight, we should even out to an average of about 100 percent,’ Janalel said, with an air of satisfaction.

Farah grinned. ‘You didn’t do so good at maths, did you?’

‘Sadly no. Pascin is the maths freak. He actually likes it. I’m more your social kind of girl. Give me people over numbers any day. What about you? I mean, no offence, but you’re an upper ngāti. You don’t have to be here. Don’t you lot just float around at mingles throwing fistfuls of xin at humble little rat-gashers? Sounds like more fun than going into the military.’

There was no hint of envy in her voice, which surprised Farah. In her experience, most people of the middle and lower ngāti looked up to her – wanted to be her. That’s just the way it was. And she knew full well that if her ngāti ever dropped in status she’d be forever looking up at the others, wishing she was one of them too.

‘Pāpā was entertaining some uppers from the Military Forum, and they were talking about the wānanga. It sounded like fun.’

It had sounded like a whole new world, an exciting world. She’d sat agog, listening to the stories of combat training and battles, partnerships and camaraderie, the chance to learn and earn points and respect. It was completely different from fashion and textiles and the empty, pleasant life that her social status afforded. More than that, it felt strangely familiar, as though she was hearing about a place she’d visited years before, although she knew she hadn’t. She’d been so enthralled, she had ignored all Māmā’s subtle attempts to remind her to pay attention to her other guests, which had ended in Māmā kicking Farah hard under the table and Farah knocking her soup into the lap of the woman seated next to her.

‘I snuck out and took the test the very next day,’ she continued, over Janalel’s shriek of laughter at the story. ‘I guess I always imagined there’d be a little more to life than floating and mingles and fistfuls and all that.’

Janalel grinned. ‘I hope so, for your sake.’ She raised her voice and addressed the viz-screen set into the wall. ‘Server – induction manual.’

The viz-screen switched from a bucolic scene of an ancient ngāti meeting hall with a flock of wenga-birds flying overhead to a page with the words ‘Welcome!’ at the top.

Farah leaned forwards to make out the closely printed type. ‘First three weeks are solo training, and then we go to partner training.’

‘And then another three weeks after that it’s the battles,’ said Janalel gleefully. ‘Three battles with three weeks in between each one, and then exams. Well, they don’t muck around, do they? We’ll be up in first class and graduating before we know it!’

‘This term we’re focusing on iri-dahs, goja-dahs and transport manoeuvres,’ Farah said, skimming the text.

‘My transport driving is pretty good. I used to drive for our farm manager, helping shift burle herds around the place.’

‘Really?’ Farah was impressed. Although burle farming, and the manufacture of textiles from their wool made up over a quarter of the Untwa income, she’d never been up close to one of the huge animals, let alone herded them.

‘Pāpā thought it would be good for Pascin and me to get some hands-on management experience. It was the only way we could earn any xin, anyway.’

Farah tried not to look surprised. All the xin she’d ever had had been given to her for … just existing, she supposed. Things were different now, though. She’d already earned fifty for figuring out how to get off the building, and the wānanga paid a bonus to trainees when they moved up a class. There was also the prospect of earning more when battles were won. Being paid hadn’t been an incentive until now. Her own xin! Earned fair and square, just like Janalel’s.

‘How are you at iri-dahs and goja-dahs?’ Farah asked.

Iri-dahs was a flowing hand-to-hand combat sport that was more about defending oneself than attacking, but could still be turned to deadly advantage. Farah’s māmā had made her take classes to improve her posture, but she had got pretty good at it. Good for Untwa, that was. Farah wasn’t sure how she’d go against an actual opponent.

‘Not great at iri-dahs,’ Janalel said. ‘I love goja-dahs though. We set up one of the barns with the gear. I used to thrash Pasc every time. It made him so mad.’

An abrupt buzz sounded on their wristbands, and the viz-screen lit up with the words ‘Sixth class, meal-room.’

‘Come on,’ Janalel said, hastily straightening her rumpled covers. ‘If we’re late we don’t get any.’

The door slid open to show the wall opposite lit with a series of dark blue arrows. Up and down the corridor, doors opened. Trainees piled out to follow the arrows, and the two girls fell into step with them.

The meal-room was four layers in from the outer wall, the limit of where their wristbands would let them go. The clear ceiling arched high overhead, the sky a brilliant shade of blue that always marked the beginning of the hot season. At a table at the far end of the room sat a few adults, talking quietly amongst themselves. Farah recognised Lieutenant Alma, and assumed others with her dressed in a similar green uniform were mentors as well. There was another group with them, sporting elaborate jewellery and hairstyles, and draped in colourful fabrics that revealed more flesh than it concealed. They, Janalel told Farah, were the associates. Trained for years in their chosen fighting discipline, they were essential to the smooth running of the battles and commanded as much respect as the mentors did.

The trainees lined up at a counter and chose from a selection of foods on display. Most were grain- and plant-based dishes, but Farah was intrigued and a little revolted to see that there were plates of steaming meats on offer as well.

‘Look,’ said Farah, indicating with her fork. ‘What animal do you think that is?’

Janalel shrugged. ‘Yaril, probably. I’ve never eaten it. But the kids from down south by the mines, they eat meat. Edible plants for humans are expensive to grow, but yarils eat anything.’

Farah wrinkled her nose. The meats smelled.

She waited as the lieutenant called out a meal prayer and then followed Janalel to a seat at the tables. Pascin dropped into a seat opposite and waved at someone in the crowd behind him. ‘Oi, Lase! Over here!’

A tall figure detached itself from the group, and Farah groaned under her breath. It was the guy with the silver tattoo. Naturally.

Pascin waved a fork, indicating as he spoke, ‘This is my sister Janalel of Perinswa, and Farah of Untwa. This is my partner, Lase of Holitarn.’

Lase gave a half-hearted chin-wave at Farah before politely brushing Janalel’s fingertips with his own.

‘Ah yes,’ Janalel said, smiling up at Lase. ‘The hero of the Hole.’

The corners of Lase’s mouth curved as he thumped down into his seat. Farah wasn’t quite sure what he found so amusing.

‘You say it like it’s a bad thing,’ Lase said.

‘Hardly,’ Pascin said. ‘When people find out you’re of the Hole, they visibly shake. That’s a huge psychological advantage.’

Farah watched Lase from under her lashes. He’d tidied his hair and had a wash and looked much better: all lean muscle in all the right places. He gave off the air of a dangerous predator, watchful and waiting, ready to spring into a blur of furious speed and motion. But the arrogance! It was coming off him in waves. She could almost feel it. And his plate had meat on it, covered with a thick layer of gravy. The sight and smell of it turned her stomach.

‘I was born in Holitarn; I’ll die in Holitarn,’ Lase said. ‘I’m not ashamed of it.’

Farah couldn’t help a little snort of disbelief.

Lase’s jaw tightened, his eyes narrowing as he stared at Farah. ‘Something you’d like to say, Little Miss Untwa? Or would you prefer to announce it in front of the whole class so that we can all marvel at how amazing you are?’

Farah’s face grew hot, and her spine stiffened. To think she’d actually been considering apologising to him!

‘It’s Farah, actually,’ she snapped. ‘And I’m not surprised you decided to climb down from the tower by yourself. With a mouth like yours, someone would have eventually pushed you.’

There was silence. Lase and Farah glared at each other across the table, silently daring each other to look away first.

Pascin whistled and Janalel let out a whoop of laughter.

‘You know what this means, Jan?’ Pascin said, his eyes twinkling.

![Tintenherz [Tintenwelt-Reihe, Band 1 (Ungekürzt)] - Cornelia Funke - Hörbuch](https://legimifiles.blob.core.windows.net/images/2830629ec0fd3fd8c1f122134ba4a884/w200_u90.jpg)