Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

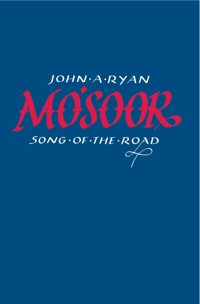

An Irish musician and a French free-thing eccentric journey through Normandy in the summertime, overcoming language barriers to form a unique friendship, the one deploying words, the other song. Walking the country lanes together, playing music for pleasure and for food, they pick up odd jobs and sleep out of doors. As they travel between villages other characters come into play: Felix, a young, sports-car-driving socialist who trades Cuban cigars for potatoes; Sir Peter and Lady Em, wealthy hosts who share their love of music. In the company of Ulick and Mo'soor, a French summer comes alive with traditional airs and renewed understandings. The timeless pastoral setting of this beautifully crafted novella echoes both Oliver Goldsmith and Guy de Maupassant, creating a unique interlude in a clamorous world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 78

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

DUBLIN

To the memory of my parents

He said his name was Monsieur Jean-Louis Ovide; my name, I told him, was Ulick MacKettrick, and with this mutually incomprehensible introduction we fell into step, as we were both headed in roughly the same direction. At the crossroads I asked him, using almost all my French and indicating the sign-post, ‘Où…?’ and he replied ‘A la carte!’ or words to that effect.

The weather was warm, the sky was blue, there was no hurry. He sang a little song, in French I suppose, then he stopped walking, smiled a whiskery kind of smile and pointed at the whistle that I carried in my pocket. We looked around. A stream bordered a wood, so we sat there in the shade and he took off his boots as I played ‘Sí Bheag is Sí Mhór’. He tapped his fingers on the bole of the tree, then leaned back and fell asleep. I followed his example.

When I wakened, Mo’soor had gone, but I felt sure that he had not walked out on me, although his boots were gone too. He returned in some excitement making signs as of diving. ‘Bassin!’ he said, so I said ‘Oui!’ wondering what he meant, and followed him up through the wood beside the stream. We reached a clearing where the water fell over a rock into a pool. This was a chance not to be ignored. We took off our clothes, left them in a sunny place and plunged in, then sat on the grassy bank to dry.

Others too appreciated the qualities of the waters of thebassin; two young women came along, saluted us cheerfully without surprise or alarm, and having filled containers from the waterfall, went back along the woodland path. When they reached a stony part of the path, however, they began to giggle, laid down their burdens, then ran back, snatched up our boots and socks and left them beyond the stony area, in spite of our shouts of protest. ‘Au’voir’, they called, smiling angelically.

‘We have managed,’ Mo’soor said, as well as I understood him, ‘to provide them with more entertainment than they expected.’

So! A philosopher!

I have forgotten the name of the place, but that was not Mo’soor’s way; when we reached the road again after our swim, he stood a while and studied the geography, the sun, the road in both directions, as though memorizing all. He mentioned the wordsiciandencore.EncoreI had heard at music sessions, not usually directed at me. But I had a new word and we set off in high humour.

Within a day or two he had become my friend, my oldest friend, my best and indispensible friend. He was good company, not talkative, content with silence, yet glad to have a fellow animal nearby. I spoke no French, I had come to France to learn it. He spoke no English but would like to learn it. With these advantages it is not surprising that we soon found out as much as we needed to know about each other, that is to say, very little, but enough.

It is not easy to learn another language. They talk too fast, or so it seems. But it is like learning a new tune. First you listen. Then you listen again. Listen and look. Listen and try. Try but get it wrong. Eventually you try and get it right. Triumph! I had a clever teacher, who quickly found the half dozen words I knew, used them and added new ones. So I soon had a small stock of mostly names: town, village, road and such. And he had the English equivalents. We were musicians, which helps; after all, it is with our ears that we learn to speak. Then camejour, nuit, dormir, nourritureand a scatter of adjectives.

Thenourritureanddormirwere a constant concern. Not at first, but when my money got scarce we still had to eat. If the weather allowed we slept out. Barns were ideal, but dogs … I tried charming the owners of the barns with music and a polite request that we might have the comfort of shelter and some hay. Sometimes it worked. There were hostels but they were a last resort.

Each of us relied on his own gifts in the important matter of acquiring our daily bread. If mine was artistic – and it was; when had those squares and market-places ever before heard ‘The Three Sea Captains’ or ‘Lord Inchiquin’ or, if I thought they deserved it, a long slow air such as ‘Aisling Gheal’ or ‘An Buachaill Caol Dubh’? – Mo’soor’s may have been equally so. I never found out exactly and did not enquire too closely. It was mentioned asLa Technique, and he did not avoid discussing it, indeed seemed rather proud of his accomplishment without being very specific. In a general way he spoke with admiration of the ability to be inconspicuous. ‘A crowd,’ he told me, ‘is the easiest place to be invisible.’ He praised keen observation and a high degree of coordination between eye and hand. I hope I have translated him accurately. So although neither of us liked big towns or cities, we found them necessary, I in order to be seen and heard while he too needed a gathering and his cloak of invisibility.

He often left me on the edge of town, in a public park, or, if the day was cloudy, in a library, or some such place, and in a short time he came back andLa Techniquenever failed to provide as good a meal as my music.

Some might say he lived on the frayed fringes of society, others, less charitably, that he preyed on it, but if so, it was done gently and with malice towards none.

We tramped the dusty roads of Normandy, the by-roads and lanes, avoiding motorways with their noise and rush. The sun rose on our left hand. We walked in the freshness of the morning, rested in the midday heat and usually dawdled through the later day until the sun sank in the west. A forest might hold us enthralled for hours. He taught me the trees and the flowers, the weeds and grasses; birds, butterflies, bees (I likedbourdon, the bumble bee) and clouds and how they were prophets of coming weathers. Frogs, toads and bats, lizards that basked motionless on warm rocks, glow-worms and stars and all the monthly shapes of the moon. I did my best to translate Yeats’s poem about the cat, Black Minnaloushe, ‘the nearest kin of the moon’. If a distant spire beckoned, or other landmark, or if our road provided little of interest, we kept walking, and might cover thirty kilometres in a day. It was understood that our aim should be to move always in the same direction, following the summer as it moved south. We thought there might be casual autumn work in the vineyards. That was the general plan. The summer sunshine was welcome; for our siesta we tried to find streams or rivers and the shade of trees.

He was something of a literary man, I found, and had two books. Well, one book and a half approximately. The complete book proclaimed itselfA Concise History of the Military Campaigns of the Emperor Napoleon I, and his library was rounded off by a once-good hardback, inside which was a French grammar that ended abruptly at page16, followed by a sad hiatus, and resumed at page41to the letter S of a glossary, and after that, nothing. However, when you consider how little luggage we could afford to burden ourselves with, his decision to keep those books was heroic. He allowed me to study them, which I did during his absences. I tried translating passages from theConcise History. ‘The big army at last advanced itself close enough’ (or was that too close?) ‘to observe the fortifications’; ‘Meanwhile the cavalry had outflanked itself …’ Could that be? Was that an example of the reflexive mode, or whatever it was called? I consulted the grammar but the reflexive part was missing. Usually I solved such problems by falling asleep. We often took short naps; an uninterrupted night’s sleep was a rare luxury.Chiens!

He liked to keep up with current events. If it was a big town he could go to a public library and have free use of various papers and journals. If he was fortunate he found a newspaper. One that he brought back was only four days old and had a very nice picture of Président Sarkozy and on another page an even nicer picture of Madame le Président. He read snippets for my information: there were problems with trade unions and students. So, nothing new there. On wet days we sheltered where we could. In country areas there might be casual work washing and packing vegetables, and even if no work was to be had, the mere asking for it would serve as a pretext for requesting shelter until the rain stopped. Mo’soor was very strict about not usingLa Techniquein such places. ‘They are good. They work hard. They are not rich.’ Fallen fruit we never took without permission. There were rules.