11,02 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WS

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

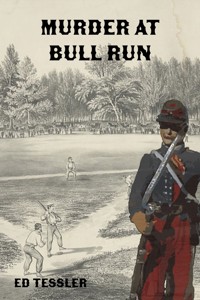

Jack Muller gets more than he bargained for when he signs up to fight with the 14th Brooklyn in April 1861. His mentor dies just after the Battle of Bull Run, but Jack is convinced that this was not just another casualty of war.

How can he prove that Michael was murdered, and how can he bring the killer to justice without damaging the reputation of Michael's beloved regiment?

This debut novel is a masterpiece of historical fiction, blending a complex murder mystery with camp life, military strategy, and the new American pastime of baseball.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 445

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

MURDER ATBULL RUNby Ed Tessler

Copyright © 2024 by Ed Tessler

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except as permitted by U.S. copyright law. For permission requests, contact tessler.edward @ gmail.com.

The story, all names, characters, and incidents portrayed in this production are fictitious, except as identified in the Afterward.

Book Cover by Eric Bunker

Published by Ed Tessler

ISBN-13: 979-8-9908515-0-4

1st edition 2024

Acknowledgements

First, I want to thank my wife Bonnie, without whose help and support this book would never have been written. Also I appreciate the valued input of my sons Danny and Nathan.

I also want to thank the Baseball Hall of Fame and the Brooklyn Historical Society for the materials they provided to me.

My friend Debra Groisser turned this book into a book, Larry Gemmell provided incredibly helpful comments, and Barbara Ismail gave many helpful pointers on writing.

Many others read early drafts of the book and provided useful suggestions. So additional thanks to Laura Philips, Geoffrey Wright, Tony Ross-Trevor and others.

PrologueNovember 20, 1861

I was resting in my tent, thinking about how far I’d come in the eight months since joining the Union army. I signed up with the 14th Brooklyn at the beginning of the war, a seventeen-year-old immigrant boy from Williamsburg. I learned how to shoot a musket and how to march and drill. I became part of the Company B base ball team. I fought in a major battle, I probably killed some rebs, and oh yeah, I solved a murder no one other than the murderer even knew had been committed.

This is how it all happened.

CHAPTER ONE April 15, 1861

In April 1861, the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter and President Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers for a three-month term to put down the rebellion. I knew I was going to enlist immediately after Lincoln’s plea. I had to get into the army and join the fight before it was over. Being a soldier who fought in a war was about the grandest thing I could think of. I pictured myself leading the charge, being the first to the enemy’s line, and grabbing their regimental colors. In my mind, there was no blood or smoke, only beautiful women giving me tokens of their affection after the battle. I knew we were fighting to save the Union and that appealed to me, a little. But what we were fighting for paled compared to the romance of it all.

I had seen the 14th Brooklyn drill, and I envied those lucky men wearing their handsome uniforms. I didn’t need any time to decide that that was going to be my regiment.

“Mama, I have something important to tell you!”

“Mein Gott! What has happened? Are you sick? Did you lose your job?”

“No, Mama, it’s nothing like that. The president has asked for 75,000 volunteers to fight against the rebellion, and I’m joining up.”

“You mean you’re becoming a soldier?”

“That’s right, Mama. I’m going to war.”

“Ach, mein baby,” my mother cried. “You can’t do that! You’ll get killed! One child only I have. There’s plenty young men who want to fight this war. They don’t need you. If the South wants to make their own rules, let them. Why should you care?”

“Mama, I’m not a baby, and I know you don’t feel that way. You love this country as much as I do. When Papa had to leave Germany, this country took us in. And I know you believe the Union should stick together. That’s the way this country was made and that’s the way it should stay. You just don’t want your only child fighting for it. Nobody does. I understand that. I’ll be careful.”

“Careful?” my mother yelled. “You think maybe I’m stupid? A soldier follows orders. If you’re ordered to do something dangerous, you do it. If you don’t do it, that’s even more dangerous because the big men in the army will punish you so bad you’ll wish you had been killed. So don’t talk to me about being careful.”

“All right, Mama, then let’s just say I have to do it.” My mother had started crying the first time the word ‘soldier’ was used. By now the tears were flowing freely. That’s the moment my father picked to arrive home. When he came in and saw my mother bawling, his eyes opened wide. He stopped in his tracks and looked at me in alarm. “What’s the matter here?”

“I just told Mama that I’m joining the army.”

My mother’s tears hadn’t changed my mind. Now I braced for another difficult conversation with my father.

“Papa,” I repeated stubbornly, “I’m going to sign up for the army.”

He surprised me.

“I knew it,” he replied. My father started stroking his chin, which he always did when he was thinking really hard about something. “When I was your age, I also wanted more than anything to be a soldier, but my papa, he wouldn’t allow it. I don’t want you to go, but I won’t forbid it. We come from a long line of scholars. I broke that line when I became a lawyer in Germany, over my father’s objections. I know you believe in this country. It has been good to us. We work hard, but we are free. I supported the revolution in Germany, but I didn’t fight. Others fighting for me; this I regret. And I had to flee the country, anyway.” My father had obviously thought about this, and was prepared for my decision. I should have realized that my papa would be a step ahead of me. How can you not respect such a brilliant man?

My father concluded, “What you feel you have to do, you should do.” I could hear my mother’s sobs in the background. “After you’ve gotten the fighting out of your system, then you’ll see what you want to do. You have a fine mind, my son. Much better than mine. I pray you survive the war so you’ll be able to use that brain.”

My father’s almost blessing made me feel worse than my mother’s crying. I promised them both I would send money home, because I knew that without my wages, things would be rough for them. I went to bed just as determined to join up as I had been before I spoke to my parents.

The next day I got up, washed, dressed, packed some clothes and, without even bothering to eat breakfast, headed over to the armory on Henry and Cranberry Streets, where the 14th Brooklyn was recruiting soldiers. There was a large number of men waiting to volunteer. I worried that the ranks would be full before they got to me. A man in a sergeant’s uniform walked down the line, asking who was ready to sign up and report for duty today. I could see that most of the men hadn’t bothered to pack anything, so they must have been counting on going home after enlisting.

I caught the sergeant’s attention and told him I was ready. He motioned me over to a separate table. I picked up my sack containing some clean clothes, a shirt, underwear and one pair of socks, and followed him. Another man in uniform told me he needed some information for the roll or register of the regiment. I gave him my height, age and occupation, then signed where he told me to. As soon as I was done signing the roll, I was directed to another area of the armory for my physical. The surgeon had me strip so he could examine me. He had me bend over, kick, and jump while he thumped my chest and back. While he was doing that, he asked me some questions to see if I was insane or an imbecile. He checked my teeth, then he held up a couple of fingers. He asked me how many he was holding up, and I said two. I guess that was the test to make sure I could see. Then he checked my hearing by whispering, “Can you hear me?” I responded yes and passed my hearing test.

I must have passed the physical because the surgeon sent me to another part of the armory to sign yet another form. In this one, I swore that I wanted to serve in the 14th Brooklyn for ninety days. I gave the uniformed man sitting behind the table my name to fill in on the form. After the soldier filled in my name, he gave me the document to sign. That’s when I noticed the surgeon had already signed the paper, certifying that I was “free from all bodily defects and mental infirmities” that could prevent me from performing my duties as a soldier. He must have signed it before my name was even on the form.

The soldier behind the table told me to stay put while he found an officer to administer the oath. He returned with another soldier in a couple of minutes. The officer was pleasant enough but didn’t even tell me his name. He just said, “Raise your right hand and repeat after me.” I then promised to “bear true allegiance to the United States of America” and serve it “against all their enemies” and “obey the orders” of the President and of the officers appointed over me.

Both men congratulated me and told me I was mustered into Company B of the 14th Brooklyn Regiment. “That was it?” I wondered. “I’m in the army now?” In the span of an hour, I went from Brooklyn boy to soldier. I didn’t feel any different. This was not the way I imagined it would happen. There was no band or ceremony. Maybe that would come later.

The sergeant told me that I would be staying in the armory overnight, and then, with a number of other new recruits, go to Fort Greene Park where the 14th Brooklyn was camped. When I got there, I was to report to Captain Mallory, who was in charge of Company B. He would tell me what to do.

My night in the armory was exciting but uneventful, if that makes sense. I was issued a blanket for sleeping, which was all I needed. A number of boys were in the same position as me: new recruits. We spent hours talking about how great it was to be in the army, and what we were going to do to the rebs. We all agreed that the war would end quickly and that we were going to make that happen. We were served a hot supper which consisted of a piece of meat, a chunk of bread, and some potatoes. It wasn’t Mama’s cooking, but it was enough.

The next day we marched over to Fort Greene Park. “March” is probably the wrong word since we didn’t know what we were doing. We walked there briskly. From the armory on Henry and Cranberry Streets, we headed down Henry Street to Clark Street, then to Tillary Street to Jay Street, and finally to Myrtle Avenue, which led us right to Fort Greene Park.

On each of these streets, I saw beautiful multi-storied homes of wood, brick, or brownstone. These were nice well-to-do areas where people kept their houses in fine condition. I also passed stores where I could look in the windows to see what I would like to have –from clothes to watches to books – but couldn’t afford.

We weren’t wearing uniforms, so strangers on the street would come up to us and ask what we were doing. When we said that we had just joined the 14th Brooklyn and that we were marching to camp, those same people started slapping us on the back and congratulating us. Pretty girls gave us flowers. I didn’t know what to do with the flowers, but it felt wonderful to get them. We were heroes before we were even soldiers. I may not have gotten the celebration when I first signed up, but this was my band and ceremony.

When we arrived at Fort Greene Park, I got separated from my group, so I asked somebody where to find Captain Mallory’s tent. I walked in the direction I was told, looking for the captain’s tent. There were rows and rows of tents of different shapes and sizes. Most of them looked like Indian teepees that I’d seen in books. Others were larger with sloped roofs and short walls, looking a bit more luxurious than the teepees. I guessed those were for the officers.

Boys in and out of uniform were standing around or sitting on logs throughout the camp. Some were writing, others were playing cards or checkers, but most were just talking. I overheard a couple of them discussing what they were going to do to the rebels when we caught them. Since neither of the boys were in uniform, I assumed they must be new recruits like me.

“Those I don’t shoot, I’m gonna stab with my bayonet,” one of them said. “You’ll have to get in line behind me,” the other replied. “You can have all that’s left over.”

I couldn’t hear anything else, but I was impressed by their confidence. I wondered if the enemy were saying the same thing about what they would do to us. If so, someone was going to be wrong.

After a while, I realized that I had no idea where I was going. I could smell food cooking and coffee brewing. The smell seemed to come from one of those larger tents, but this one had no sides. It was the kitchen, and it looked like the folks working there were boiling everything, and I guessed that was their favorite way of preparing meals. I saw someone in uniform sitting on a log reading a book, so I went over to him to ask where to find Captain Mallory’s tent. Since he was in soldier’s attire, I figured that he’d been in camp for a while, and would know his way around.

“Excuse me, can you help me out?” I asked.

“Sure,” he replied. He closed the book and gave me his full attention. “Are you one of the new recruits?”

“Yes, I am. My name is Jack Muller.”

“I’m Michael Gorman. Pleased to meet you.” We shook hands, which seemed like the right thing to do.

“Sorry to interrupt your reading, but I was wondering if you could tell me how I could get to Captain Mallory’s tent?”

“Of course. I was just reading this book on military tactics, which can wait. I'm not getting much out of it.” Michael sighed. “The author is a Prussian officer, and the translation is not very good. If the translator didn't know the correct English for some German phrase, he just didn’t translate it. That makes for difficult reading.”

“Maybe I can help. I can read German. Let me see the phrases that are giving you a problem.” I sat down on the log and joined Michael. We spent about twenty minutes while I translated the phrases from German to English. “Anything else?” I asked.

“No, that’s all of them for now. Thanks so much for your help. You’re a real lifesaver. I don’t know what I would have done without you. Now I know who to go to if I get stuck on the language again.”

“Anytime, glad to help.”

“Let me show you around camp, and then take you to George’s - or rather Captain Mallory’s - tent. It’s the least I can do for you after all your help.”

We walked around camp while Michael pointed things out and described them to me. “A camp is like a little city,” Michael said. “You see those teepee-looking tents? Actually they’re called Sibley tents. Soldiers live in them. ”

“Why are they called that?”

Michael shrugged. “I don’t really know, but I figure they must have been invented by some man named Sibley, who liked the look of the Indian teepees. They’re pretty roomy inside, and can hold four or five men real comfortably, or up to a dozen men uncomfortably. Right now we’re trying to build up our strength, so the Sibley’s aren’t fully occupied. The problem with the tents is that they’re really hard to take down and move. You need wagons to relocate those long poles that hold them up. And with all the other things that an army has to transport, you don’t want big posts taking up wagon space.”

“What about those tents over there?” I pointed to a group of tents that look like the letter ‘A’ with the ends cut off.

“They are called wall tents. The angles at the bottom are replaced with straight up and down sides. That size is for commissioned officers. Those walls at the bottom around the tent make them more comfortable because you can stand up easier in them. Commissioned officers don’t have to share their tents.” Michael talked like a teacher speaking to children. It was perfect for me since I didn’t know anything, and there was so much to learn about camp life.

Michael was still talking. “That real big structure over there is the hospital tent. I hope you don’t ever have to see that one up close, but if you go on sick call that’s where they put you. There’s another big one with open sides that you can’t see from here. That’s the cooking tent where the regiment’s meals are prepared. There are other smaller tents with side walls for administrative duties like processing enlistments and doing the paperwork that goes with running an army.

“I’m sure you’ve noticed a lot of the boys just kind of lolling around. There’s a lot of down-time in the army and the soldiers use it in different ways. I was reading because I already finished writing a letter to my wife. But you can see for yourself that some of the boys are writing, and others are playing games or just bragging about what great soldiers they are. Truth is, most of them have never been in a fight.

“It will help you find your way around if you know that each company has its own area with its own flag. So to find Captain Mallory, you would look for the Company B flag and go to the tent next to the flag. That’s where you’ll find his staff who could tell you whether the captain can see you.

“See,” he said, pointing, “There’s the flag for Company B, and I see Lieutenant Uffendill outside.”

“Hey, Isaiah,” Michael said. “Let me introduce you to Jack Muller. He’s one of the new recruits. Jack, this is Isaiah Uffendill, or rather Lieutenant Uffendill, who is the adjutant for Captain Mallory. Isaiah, Jack was instructed to report to George for duty.”

I was surprised at the informality between a soldier and an officer, but Lieutenant Uffendill didn’t seem to think anything of it.

“Nice to meet you, Private Muller,” he said. “Captain Mallory is busy right now. Come back in a while, and the captain will be able to see you.”

“That works out well,” Michael said. “I can keep showing Jack around, and we can talk some more. See ‘ya, Isaiah,” Michael said with a salute that looked more like a wave. We walked off together.

I couldn’t stop myself from asking, “Michael, are we allowed to be so familiar with the officers?”

“Actually, you’re right. I should keep to the formalities more, now that we’re adding new recruits. I don’t want to set a bad example that will affect regimental discipline. Isaiah and I go back a long ways and the regiment was more casual before the war. You see, officers in the volunteer army are elected by the soldiers. So generally, there’s kind of an informality between them because the officers need the soldiers’ vote. But I have to be more careful. Thanks for making me aware of it, Jack.”

I was surprised at the way Michael accepted my question as criticism, and then accepted the criticism without being defensive. Since he was an old timer in the regiment, I was flattered that he listened to me at all, let alone admitting that I was somehow right. Michael impressed me.

As we walked around some more, Michael asked me about myself. Surprisingly, he seemed really interested in my answers.

“There’s probably not a lot to tell,” I began. “I’m seventeen, and I’ve lived in Williamsburg for almost twelve years since my parents came over from Germany.”

“You don’t talk like a German,” Michael interrupted.

“I was young when I came here and anyway my father is very insistent that now that we’re in America I shouldn’t speak like a foreigner. My Papa was an attorney back in Europe, and he ran into some political trouble, so we had to leave. He can't practice law in this country so he’s a laborer here in the Navy Yard. He always wanted me to follow in his footsteps. He thinks that an American lawyer shouldn’t speak like a German, just like a German lawyer shouldn’t have an American accent.”

“What’s an American accent?” Michael asked, smiling. I laughed because I knew what he meant. Americans think that the way they speak is the right way. So there is no American accent.

“Anyway,” I continued, “ever since I could read, my father made me read aloud books like Shakespeare and the Bible to correct my English, and teach me not to speak like an outsider. My father didn’t even want me to talk like my friends because he said they didn’t use proper English. Funny, I think his speech has improved because of all his work with me.”

“Is that why you want to be an attorney; because your father wants you to be one?”

“I guess that was it initially. From the time we got to this country that was all my father said, but I started to have second thoughts. You know, why should he be deciding something like that for me? Then I realized that just because my Papa wanted it doesn’t mean I shouldn’t. I work with him in the Brooklyn Navy Yard and that life isn’t easy. We couldn’t afford a lawyer if we needed one. Lots of people are in the same position, or worse. As an attorney I can help them. My father did that in Germany. We were not rich, but we lived comfortably. That’s what I want to do.”

“Is your dad bitter about being a laborer in this country when he was a lawyer in Germany?” Michael asked.

“Not at all,” I replied. “He says he’s grateful to this country for giving him a job, and for the hope that his son will do better.”

“It sounds like your dad was pretty successful in Germany. Why did he leave? What do you mean when you said he ran into ‘political trouble’?”

“He did all right,” I spoke slowly as I recalled our life in Germany. “Papa doesn’t talk about it much, but I heard enough to know his leaving had to do with the unsuccessful revolution against the Emperor in Austria. He wasn’t one of the ones fighting in the streets but he supported the liberal views of the revolutionaries. After the revolt failed, folks started turning in people. Those people then turned in others. One day, my father found out he was named as being a part of the revolt. So we left Germany fast.”

“It seems to me you should be really proud of your dad. He’s made a new life for himself in a new country, and he’s looking toward the future -- you. Do you have any brothers or sisters?”

“No,” I answered. “I’m an only child. That’s one of the reasons I haven’t tried to start reading for the law yet. My Papa’s work in the Navy Yard doesn’t pay all that much. As he said, he was lucky to get that since he doesn’t have any building skills. He had some friends from Germany who already worked at the Navy Yard, and they helped him get the job.

“I give the money I earn in the Navy Yard to my parents. Between the two salaries, we live okay. I know a bit about clerking in a law office. A clerkship is hard to get and most don’t pay much if anything. My family can’t afford to have me clerking for nothing just to be able to read for the law. When I signed up with the army, my parents didn’t say anything about money, but I know they must be worried about how they’ll make ends meet. I plan on sending my folks most of my army pay. That should be enough, with my father’s wages, to let them keep on living the way they have been.”

Michael seemed genuinely impressed. “I hope your plans work out. I know it’s hard to get one of those clerkships in a law office because it often goes to relatives or friends of the attorney. But maybe I can help you. My father-in-law knows a lot of important people.”

He motioned to a nearby log where we could sit and continue our conversation. “Before the war the 14th Brooklyn was much smaller than it is now, with most of the men from Brooklyn Heights.” I recognized the Heights as the area where the wealthy lived. “With President Lincoln’s call for volunteers, we’ve already increased in size seven times, and we’re getting German and Irish immigrants and the sons of those immigrant families. Having those kinds of different backgrounds in the group is a good thing. We used to be all pretty much the same, and that’s just not the way life is. I like the different kinds of recruits that we’re getting. I think it will make us a better outfit.”

“Well, I’m proud to be in the 14th,” I said earnestly. “I’ve heard great things about it, and I hope I do right by the regiment.”

“I’m sure you will, Jack. If you’re interested, I can tell you about our history.”

“Sure, I’d like to hear that.”

“About fifteen years ago, the New York State militia was re-organized by combining units to reduce the number of regiments. The 14th Brooklyn was created with two companies. A company has about a hundred men in it. Colonel Willets and then Colonel Phillip Crook were appointed as colonels. After that, it became like other militia regiments, electing its own officers.” Michael again sounded like a teacher speaking to his class, but I didn’t mind. He was giving me a lot of information, and I was interested.

“Crook was followed by Jesse Smith as elected colonels. About a year ago, Smith was promoted to brigadier general, and A. M. Wood, who had been a major, jumped up to colonel. Below Wood is our lieutenant colonel E. B. Fowlerand and James Jourdan is our major. Right now there are eight companies in the regiment, each with its own elected officers.

“Before the war, the 14th Brooklyn was kind of a social club for well-off men. Our old armory was on Henry and Cranbury Streets in Brooklyn Heights. The men would get together on evenings or weekends for recreation and to show that they were ready to serve if the need arose.

“Now that the war has started and President Lincoln has requested volunteers, we are seeing the number of men in the regiment increase many fold, and, like I said before, they come from all walks of life, unlike the old social club. You know Brooklyn is the third largest city in the country, and many of the people in it are immigrants so I think we‘ll see Irish, Germans, Italians, English, French and Canadians in the group real soon.”

Michael continued, “Don’t let all this confuse you. What you should know is that the 14th has a proud history. The men know this, and nobody wants to let the regiment down. We’ve done real service for the country. We were called out to suppress riots in Brooklyn after some crazy person calling himself the Angel Gabriel had whipped the people into a frenzy.” Now he really sounded like a teacher. “Just recently we were sent out to the Navy Yard where you worked, when people thought that rebel sympathizers were going to attack it. Do you remember seeing us there?”

“I do. I thought you boys were grand. That day was one of the reasons I wanted to join this regiment.”

Michael nodded his head like he understood and said, “The 14th Brooklyn also has been a show piece for the militia. We took part in the reception for the Prince of Wales when he visited America, and whenever there is a military parade, we are asked to be in it.

“I think that once you settle in here, you’ll be as proud of the outfit as I am. Let’s keep walking so I can show you more of the camp.”

CHAPTER TWOApril 17, 1861

As we were walking along, two fellows approached us.

“Jack, I’d like you to meet Peter Glasson and Robert Lewis. They’ve been in the regiment for a while.”

Peter was heavyset with the beginning of a pot belly. He had a mustache and curly blonde hair atop his six-foot frame. Although big, Peter looked soft, like he wasn’t used to doing heavy work, or even a lot of activity. Robert, on the other hand, was medium height, medium build with brown hair and brown eyes. Nothing about him stood out.

Peter was the first to speak. “Good day to you, Michael. It’s a pleasure to meet you, Jack. Any friend of Michael’s is a friend of mine.”

“Yeah, me too,” said Robert.

“We were just taking a constitutional around the camp, noting many of the new faces like yours, Jack.”

“Yeah,” said Robert, who looked bored.

“I was explaining to Robert how medieval art has shaped today’s architecture.” I then understood why Robert looked so uninterested.

“Yeah,” repeated Robert, this time rolling his eyes. Peter couldn’t see the movement, but Michael and I could.

“I believe we shall continue our little stroll, and allow you two to continue whatever it is you were doing.”

“Yeah, sure,” said Robert in a resigned tone. And the two of them walked on.

Michael turned to me. “I hope you’ll get to know them better. Peter is very well educated, and I am afraid he likes to show it off whenever he can. He’ll never use a small word when he can find a big one. His father is a doctor from a wealthy family, so Peter has been able to attend a number of colleges, looking for the area that interests him. I feel kind of sorry for him, because he hasn’t found his subject yet. When the war broke out, he was studying medieval history which he said was his passion. Unfortunately, he has also said that about a number of other fields that he’s studied, like law, music and art.”

“I can’t feel sorry for someone who’s had the opportunity to study law, and rejected it. If anything, I feel jealous.”

Michael responded quickly. “Don’t be jealous of anyone in this outfit. They all have their problems, believe me. Peter may have had every opportunity to find whatever he wants to do, but that’s not to be envied. Rather, pity him for his inability to find his calling.” I didn’t understand what Michael meant. People in my neighborhood couldn’t turn down a job just because they didn’t like it. Before I could say this Michael was moving on to Robert.

“Robert’s family controls Brooklyn politics. Robert can have anything he wants. But he doesn’t want anything from his family. So where does that leave him? Again, don’t envy the opportunity. Rather, feel sorry for a life at sea, not knowing what he wants to do. Robert’s efforts to find his own way have led him down some bad paths. People took advantage of him, and Robert made a number of bad investments. That’s why he sometimes seems sad or angry. But Peter and Robert are both good men. I hope the army gives them the direction they need.”

“You know, Michael, we’ve talked about me and some of the other boys, but I don’t know anything about you.”

“Jack, I’m far less interesting than you. I’m an only child, too, but I always wanted a little brother. My parents were well-to-do, but unfortunately they both died of influenza in June 1857. I’m blessed that they were around as long as they were, and that they left me well provided for.

“Peter, who you just met, introduced me to my wife, Elizabeth, who is the finest woman in the world. I never get tired of telling the story. It was pretty funny at the time. I was working in the Brooklyn Savings Bank, and Elizabeth’s father is the president of the bank. But I didn’t know Elizabeth. So when Peter found out where I was working he introduced me to Elizabeth, who had known Peter since they were children. Peter thought the whole thing was very amusing, meeting the boss’s daughter and all. Peter arranged it so that he and I were walking down Henry Street in Brooklyn Heights at the same time that Elizabeth takes her Sunday stroll there. I think Peter believed it would be funny to introduce us and say, ‘Michael, meet your boss’s daughter, Elizabeth.’ Well, I fell in love with her as soon as I saw her and I guess she fell in love with me, because we were married within the year. I’m a very fortunate man: a wonderful wife at home, and a great career opportunity at the bank. Then war broke out and the 14th Brooklyn was called on to do its duty.”

Michael reminded me of my father. He wasn't bitter about getting pulled away from his wife and job, just as my father was not bitter about being a laborer even though he had been an attorney in Germany. Rather, both of them were grateful for the lives they had.

Without even realizing where we had walked, we were back at the captain’s tent. This time Lieutenant Uffendill led us inside. Michael introduced me to Captain Mallory, who welcomed me to Company B. The captain directed Lieutenant Uffendill to get me quartered. The lieutenant told me that I would be sharing a tent with Bernard Carney, and that he would show me where it was. Michael offered to take care of that.

Michael, Captain Mallory and Lieutenant Uffendill all seemed comfortable together. This must have been the informality Michael told me about. In thinking about it some more, I realized it wasn’t so surprising given that these people had known each other socially for years outside of the army.

Michael and I walked out of the captain’s tent so he could show me where I would be sleeping.

“As long as we’ve got the time, Jack, let me tell you what the routine is around camp. They run this camp like a regular military outpost. You’ll learn to react to the sounds of bugles and drums. There are about sixteen different signals that the bugles and drums use to tell the soldiers in camp what to do.”

“SIXTEEN! I can’t remember all that!” I felt a little panicked.

“Don’t worry, you’ll get used to it. The army is all repetition and drill, drill, drill.

“At five o’clock in the morning, reveille is blown by the head bugler to alert the drummers. That’s the signal to prepare for the morning roll call. Fifteen minutes later, the drummers sound reveille for the regiment to assemble.”

“What do you mean by assemble?” I asked.

“That’s where men gather for roll call. And before you ask, roll call is where they make sure no one has left camp without authorization, by counting who is present or has a good reason not to be present. When assembly is sounded you’ll see men rushing out of their tents, some of them half-dressed, to form up on the drill field over there,” Michael said in his teacher tone, pointing to an open field at the end of camp, “so that they can be noted as present. All soldiers except for those on guard duty and those on sick call must be at roll call unless they’re excused for a really good reason. After the men have formed up in line, the duty sergeants, each of whom is in charge of about twenty-five men, call the names of everyone in that group. The sergeants then report to the orderly sergeant that all the men are present or accounted for. The orderly sergeant reports that information to the officer of the day. If any of the men are not there or accounted for, they are considered deserters unless some good explanation can be given. That’s why all the men race out when assembly is sounded.

“What happens after roll call?” I asked. “Can we do whatever we want?”

“Following roll call, if there are no special orders or instructions, the line is dismissed. Then during the day, the drummers will signal us to do whatever activity is scheduled.

“We have different duties for which we are responsible until breakfast call is sounded. When we hear that, a representative from each tent goes to the cook house to get the food for his tent.”

“Why don’t the men just line up and get their own food?” I asked.

“The whole process would just take too long if every soldier had to line up to get his own food. Imagine eight hundred or a thousand men lined up for their food. The line would stretch on through the whole camp, and the wait for food would be terrible. Instead, one representative gets the food for his tent, takes it back, and distributes the food to his tent mates.”

“How does each tent decide who has to get the food?” I asked.

“Oh, each tent has its own system for dividing up responsibilities, like who gets the food, who gets water, or who cleans up. That system has worked pretty well so far.

“When sick call is sounded, if someone is not well,” Michael continued, “this is the time where the ill soldier would go to the hospital tent to see the surgeon. After breakfast call comes fatigue call where we are assigned things like cleaning up the camp, getting wood for the cook house or the officers, or doing other things that have to be done in an army camp.”

“Sounds like we’re going to be pretty busy. What’s next?”

“Drill call. In the mornings we usually do squad drill rather than company or regimental drill. You should know that a squad will have about twenty-five men in it, while a company like Company B will have about a hundred men at full strength, and then the regiment is made up of eight to ten companies so it will have 800 to 1000 men in it. That’s about what I expect we’ll have when we are at full strength.”

“So you’re saying that even though you and I are both in Company B, we might not be in the same squad?”

“Exactly! You catch on quickly.”

Michael continued explaining the various daily calls. I wondered how I would ever remember all of this information and shivered at the thought of being punished for forgetting something. “At twelve o’clock dinner call is sounded, and the representatives report again to the cook house tent for their food. In the afternoons, the drilling is for the entire regiment to practice the maneuvers that it will have to use in battle. Five o’clock is supper call, and at about six o’clock assembly is blown again so that the men can line up for roll call again. This roll call is also known as the dress parade where all general orders are read and lectures may be given to the soldiers.”

I interrupted. “Is that roll call done the same way as the morning one?”

Michael nodded his head. “Exactly the same. Then at about eight thirty, assembly is sounded again for the final roll call of the day. It is done just the same way it is done in the morning and in the afternoon, and then the company is dismissed. After the evening roll call, the men have half an hour to make their beds and get ready for sleep. At nine o’clock, retreat is sounded, and then all lights are supposed to be put out, all talking and other noises stop, and every man except the guards should be inside his quarters. That’s about what your days will look like, Jack.”

“That sounds like a really long and busy day. But earlier, we saw a lot of boys that were just lolling around. There seems to be a lot of time when people aren’t doing anything.”

“Yes, that’s true. You’ll be surprised at how much free time there is, and that’s what separates good soldiers from the others,” Michael said. “You can use that free time to play cards, joke around with the men, or do an awful lot of other things that aren’t going to make you a better soldier. I try to read manuals so I know what we’re going to be doing when we get into battle. That’s what I was doing when we met. You really helped me a lot with that German book I was reading. You might want to think about becoming familiar with some of the manuals that tell you why you’re doing the things you’re doing in training to prepare you for battle.”

“I don’t have any manuals.”

“That’s no problem. I could lend you some if you’re interested.”

“Sure, since I signed on to be a soldier, I might as well be a good one.”

“I thought you’d feel that way,” said Michael. “Let me get you the first volume of Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics which is a basic training manual. It will show you the way an army fights as an army. If you finish it and want to look at the second volume, I’ll be happy to lend you that one, too.”

“Thanks, Michael. I really appreciate the offer, and I’ll certainly read the manuals.”

By then we were in front of my tent. Michael said, “You’ll be sharing this tent with Bernard Carney and some other new recruits. Bernard is a good man, but he spends most of his time trying to find out camp gossip. The problem, though, is that you can’t trust Bernard to keep a secret. He would be a better soldier if he spent more time soldiering and less time gossiping. I’m telling you this in advance because from what you say, you’re serious about becoming a good soldier. You’ll get along fine with Bernard, but just don’t get caught up in all the gossip.”

When we looked in the tent, Bernard was lying down. Michael introduced me, then said he had to be going. He told me that we’d see each other soon, and promised that he would get me the manual. Michael left, and I threw my sack containing all of my spare clothes on the floor.

The tent was more spacious than I expected. It was shaped like the Indian teepees I’d seen in pictures, and was about fifteen to eighteen feet in diameter and about twelve feet high. The tent was supported by only one long pole in the middle that used a tripod about three foot high at the bottom to hold the pole up. At the top was an opening about a foot in diameter. I guessed that the hole at the top was how air got into and out of the tent.

I introduced myself to Bernard, who immediately asked, “Well, Jack, what do you think so far?”

“Michael was just showing me around and explaining how things worked around here. It looks pretty good to me. Say, how many boys can sleep in this tent?”

“It can hold about a dozen if they lay like the spokes on a wheel, with their feet at the center. But I don’t think we’ll have nearly that number. The regiment is not at full strength. We’re still recruiting.”

“I see. But one question, though. What do we do when it rains, with that hole at the top of the tent?” I asked.

“Oh, that’s no problem. We have a flap that we put up there to cover the hole when it rains. In cold weather we can use a stove in here, and run the stove pipe through the hole. It should all work pretty well. I don’t think we’re going to be here in cold weather anyhow. I suspect we’ll be moving south pretty soon.

“I have to tell you, Jack, that Michael is a strange man. He could have been an officer if he wanted. The men like him and respect him. He would have been elected easily. Instead, he just wants to be a private along with us other soldiers. There’s some story there, and I don’t know what it is.”

I could see what Michael meant when he said Bernard was a gossip. I vowed not to give Bernard any information that I didn’t want made public. “Maybe that’s just the way Michael wants it. Maybe he thinks just being a soldier is how he can do the most for the regiment, and himself. Not everyone wants to be an officer. I figure most of what the officers do is to stay back behind the line and send other boys out to do their fighting for them. That’s not something Michael would want, I bet.”

“Maybe,” Bernard replied. “But before the war I was a reporter for the Brooklyn Eagle so I kind of see stories everywhere. Funny thing about the Eagle. Do you know what happened? Before the war it was pretty much pro South. I suspect that was because of all the trade that was done with the South coming into the Brooklyn ports. But for whatever reason, the Eagle was of the opinion that the South should be left alone. But once those rebs fired on Fort Sumter, boy did the Eagle change its mind. Now the Eagle wants the South whipped fast and whipped good. That’s my view, too. I figure if some newsworthy story comes along while I’m here helping to beat the South, that’s all to my benefit. I can send a letter to the Eagle, which publishes soldiers’ letters. Then I sort of get credit for the story. That will help me after the war when I try to get my job back.”

As he talked, Bernard kept stroking his brown mustache which was really just some wispy hairs on top of his lip. He was thin and of medium height. You could see that he’d worked indoors before the war because there were no sun lines, or any kind of lines on his face. In fact he had kind of a baby face, and I guess he grew the mustache to make him look older. Even with the mustache, however, he still had a boyish look about him.

I played along with his role as a reporter. “If a story comes in, I’m sure you’ll be the first to hear about it.”

“That’s my idea,” Bernard replied. “You have to keep alert to find out everything you can. Most of the stuff isn’t worth the effort, but when that nugget comes along, you want to be there to get it. I’m going out now to talk with the boys some more, and see if there’s any news about what we’re going to do. If you need anything, just let me know. My stuff is over there, and you can feel free to share my razor.”

I think Bernard made me that offer to point out that he “used” a razor. I hadn’t brought one because I didn’t really need it yet. But it was a nice enough gesture anyway.

“I’ll see you later then, Bernard. I’m just going to stay here and get settled in.”

“See ya later,” Bernard said as he left.

I spread out the bedroll, which was part of the equipment I was given by the quartermaster, and lay down to try and think about army life so far. Before I had much of a chance to think, two men came into the tent. Actually it was more like one older man, bald but with a full beard, and one young boy. The older man introduced himself as Patrick Murphy, and the young one was Davey O’Connor. Patrick looked old enough to be my father. He was stocky, but it looked to be all muscle. I thought he was in pretty good shape for a man his age--fit as a fiddle. Davey, on the other hand, was thin, small, no more than five feet three inches. I’m seventeen and he looked much younger than me. They both looked about as nervous as I felt before I met Michael. I supposed they hadn’t had the good fortune to meet someone like Michael to show them around and take the edge off their nervousness.

“I’m Jack Muller,” I said. “Today is my first day here.”

“Me, too,” Patrick and Davey replied almost as one.

Davey continued speaking as if he was excited to tell me something. “I got to the tent a while back, and I seen Patrick just sitting there. We got to talking. Turns out Patrick and me are both Irish, although my family’s been in Brooklyn a lot longer. Ain’t it something to run into another Irishman my first day?”

“It sure is,” I replied. “Wonder what else we might have in common. I worked in the Brooklyn Navy Yard before I signed up, and one day I hope to be a lawyer. I’ve got no brothers or sisters. My parents didn’t really want me going off to fight this war, but I thought I should. What about you, Patrick?”

“I have me a wife and three children. Sure I couldn't find work so I signed up thinkin’ that even if this was only ninety days long, I could get some money for me to take care of my family. I had to lie about my age to get in, didn’t I now? Told them I was thirty-eight when truth be told I’m fifty-seven.”

“I lied about my age, too,” Davey chimed in proudly. “Told ‘em I was eighteen, when I’m really fourteen.”

They both spoke with lilting Irish brogues, but Davey’s was much less noticeable than Patrick’s. I figured that Davey had come to this country when he was very young, while Patrick was probably a more recent arrival. I could easily understand what they said, and I was concerned for them. “Be careful. You don’t want the fact that you lied about your ages to get around.”

“Why not?” Davey asked. “We’re already in the regiment. They can’t kick us out. Anyways, why would they give a hoot?” Patrick and Davey were chuckling like they had gotten away with something.

“Yes, they can kick you out!” I was shocked at how unaware they were. It was one thing for fourteen-year-old Davey to be so innocent, but Patrick was a grown man. “The army has rules that they stick to. If someone breaks those rules the army can, and probably will, take action. If an officer finds out about your lies and doesn’t do anything, then he has lied, too. No one is going to take a chance on being punished for helping you lie to the army. Have you boys told anyone else about your real ages?”

“No, we just got here,” responded Patrick. His eyes, like Davey’s, were wide open, and they had lost some color in their faces, and their smiles were gone.

“That’s good, and you should keep it that way. Don’t worry about me, I won’t tell anyone.”

Patrick’s eyes narrowed suspiciously. “Why would you not tell ‘em our secret? Did you not just say that you must be telling them or else you lied about our ages, too?”

“That’s only for officers.” I may have made that up, but it sounded right. I didn’t see myself as a stool pigeon and had no reason to turn them in. As far as I could tell from our brief conversation, they seemed like decent fellows who would make good tent mates. “What you have to worry about is someone else, for whatever reason, telling one of the officers about your real ages. We’ve got another tentmate named Bernard Carney who seems nice enough, but he’s quite a gossip. He was a reporter for the Brooklyn Eagle, and he’s always looking for information that he thinks would make a good story. By my judgment he doesn’t particularly care who he tells this information to. So you boys better keep your real ages a secret.”

“Why would he tell on us?” Davey asked.

“I think he just likes to show off whatever he knows. Or maybe he’s a stickler for the rules; or maybe he thinks it will make the officers like him more. I don’t know what his reason might be, but you boys can’t take the chance.” I called them boys, even though Patrick was older than my father, because that’s what I called all the soldiers who weren’t officers.

They considered what I had said, and apparently decided that I was worthy of their trust. They both thanked me for helping them, looking sincerely grateful.

“How come you couldn’t find work?” I asked Patrick.