9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

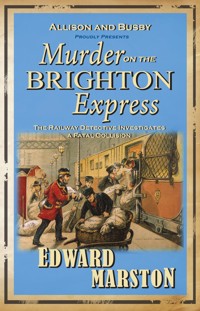

- Herausgeber: Allison & Busby

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: Railway Detective

- Sprache: Englisch

October 1854. As an autumnal evening draws to a close, crowds of passengers rush onto the soon to depart London to Brighton Express. A man watches from shadows nearby, grimly satisfied when the train pulls out of the station. Chaos, fatalities and unbelievable destruction are the scene soon after when the train derails on the last leg of its journey. What led to such devastation, and could it simply be a case of driver error? Detective Inspector Colbeck, dubbed the 'railway detective' thinks not. But digging deep to discover the target of the accident takes time, something Colbeck doesn't have as the killer prepares to strike again.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 398

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

MURDER ON THE BRIGHTON EXPRESS

EDWARD MARSTON

To Peter James,

Contents

Title PageDedicationCHAPTER ONECHAPTER TWOCHAPTER THREECHAPTER FOURCHAPTER FIVECHAPTER SIXCHAPTER SEVENCHAPTER EIGHTCHAPTER NINECHAPTER TENCHAPTER ELEVENCHAPTER TWELVECHAPTER THIRTEENCHAPTER FOURTEENCHAPTER FIFTEENAbout the AuthorBy the Same AuthorCopyright

CHAPTER ONE

1854

Hands on hips, Frank Pike stood on the platform at London Bridge station and ran an approving eye over his locomotive. He had been a driver for almost two years now but it was the first time he had been put in charge of the Brighton Express, the fast train that took its passengers on a journey of over fifty miles to the increasingly popular town on the south coast. Because it did not stop at any of the intervening stations, it could reach its destination in a mere seventy-five minutes. Pike was determined that it would arrive on time.

A big, sturdy, shambling man in his thirties, he was a dutiful and conscientious employee of the London Brighton and South Coast Railway. His soft West Country burr and gentle manner made him stand out from the other drivers. Pike was a serious man who derived immense satisfaction from his work. Arriving at the shed an hour before the train was due to leave, he had read the notices of speed limits affecting his shift then carefully examined all the working parts of his locomotive, making sure they had been properly lubricated. Everything was in order. Now, minutes before departure, he felt a quiet excitement as he stepped on to the footplate beside his fireman.

‘How fast are we going to go, Frank?’ asked John Heddle.

‘We keep strictly to the recommended speeds,’ replied Pike.

‘Why not try to break the record?’

‘It’s not a race, John. Our job is to get the passengers there swiftly and safely. That’s what I intend to do.’

‘I’ve always wanted to push an express to the limit.’

‘Then you can do so without me,’ said Pike, firmly, ‘because I’m not taking any chances, especially on my first run. Excessive speeds are irresponsible and dangerous. You should know that.’

‘Yes,’ agreed Heddle, ‘but think of the excitement.’

John Heddle was a short, skinny, animated man in his twenties. He had a mobile face that featured a bulbous nose, a failed attempt at a moustache, a lantern jaw and a permanent gap-toothed grin. Having worked with the fireman before, Pike was fond of him though troubled by Heddle’s impulsiveness and lust for speed. They would be glaring defects in the character of a driver. Pike had impressed that fact upon him a number of times.

After a final check of his instruments, Pike awaited the signal to leave. It was Friday evening and the train was filled with people who either lived in Brighton or wished to spend the weekend there. One of the passengers, a clergyman, suddenly materialised beside them.

‘Good evening to both of you,’ he said, amiably. ‘Do excuse me. I’ve just come to bless the engine.’

‘Bless it?’ said Heddle with a laugh. ‘It’s the first time I’ve heard of anyone doing that, sir. What about you, Frank?’

‘It’s been sworn at before now,’ said Pike, ‘but never blessed.’

‘Then you can’t have driven the Brighton Express,’ decided the newcomer, ‘because I travel on it regularly and always bestow a blessing on the engine before departure.’

He closed his eyes and began to offer up a silent prayer. Driver and fireman exchanged a glance. Pike was mystified but Heddle was highly amused. The clergyman on the platform was a diminutive figure of middle years, jaunty, dapper and good-humoured. He had long, wavy, greying hair and a goatee beard. Even in repose he seemed to be bristling with energy. Pike was afraid that the blessing would go on too long but the clergyman knew exactly how much time he had at his disposal. Opening his eyes, he gave them a broad smile of gratitude then stepped smartly into a first class carriage near the front of the train. Thirty seconds later they were in motion.

‘There you are,’ said Heddle, nudging the driver. ‘You’ve got the Church’s blessing now, Frank. You can go hell for leather.’

Pike was circumspect. ‘We’ll maintain the speeds advised,’ he said, solemnly. ‘Then we can be sure to arrive in one piece.’

The Reverend Ezra Follis was comfortably ensconced in his seat. He was on nodding terms with two of the male passengers and recognised another, Giles Thornhill, a tall, spare, beak-nosed man with pursed lips and an air of supreme arrogance, as a Member of Parliament for Brighton. Having severe reservations about the man’s suitability as a politician, Follis had never voted for him nor tried, on the few earlier occasions when they shared a carriage, to engage him in conversation.

Two people caught Follis’s attention. One was a big, solid, red-faced fellow with mutton-chop whiskers decorating both cheeks like ivy spreading across the walls of a house. When he realised that he was being scrutinised, the man gave a loud sniff of protest before disappearing behind his newspaper. Diagonally opposite Follis was an altogether more interesting subject of study, a slim, attractive, auburn-haired young woman, impeccably dressed and well-groomed. What diverted the clergyman was the fact that some of the other men in the carriage were pretending to read or stare through the window while shooting her surreptitious glances of admiration. Smiling tolerantly, Follis opened his Bible and searched for the text on which he would base his sermon the following Sunday.

Driving an engine was a test of concentration. Since the footplate was unprotected, Frank Pike and his fireman were exposed to the elements and to the clouds of thick, black smoke bursting rhythmically out of the funnel. As well as listening for any defects in the operation of the engine, the driver had to keep a wary eye on the line ahead for any potential hazards. Even on such a clear, warm summer’s evening, visibility over the engine from a juddering footplate was not ideal. There was an additional problem. Those who designed locomotives had somehow never thought to provide seating. Both men had to stand throughout the entire journey.

The route took them almost directly southward across the grain of the Weald. It was undulating landscape. When they steamed through Norwood, they had to climb a seven-mile rise towards a gap in the crest of the North Downs. There was a long cutting through the chalk before they plunged into the Merstham Tunnel, over a mile in length. Emerging back into the light of day, the train had over seven miles of down grade, easing the strain on its engine and effortlessly gathering speed. After shooting past Horley, they began another gradual climb to a summit pierced by the Balcombe Tunnel.

Pike knew every station by heart, having stopped at them regularly when in charge of slower trains. Stationmasters and porters gave him a friendly wave as he rattled past. He felt an upsurge of pride at being on the footplate of the Brighton Express. When it was first built, almost the entire line passed through open country with only a few cottages punctuating the scene. Signs of habitation had slowly increased now as people sought a rural escape that was yet within easy reach of a railway station. Cows, sheep and crops, however, still dominated the fields on both sides of the line.

Out of the Balcombe Tunnel they hurtled and started another descent, speeding on until they crossed the thirty-seven arches of the Ouse Viaduct, one of the engineering marvels of the day. Pike was enjoying his initial run on the Brighton Express so much that he released one of his rare smiles. The thunder of the train and the fierce rush of wind precluded any conversation at normal volume. When his sharp eyes spotted something ahead of them, therefore, Pike had to shout to make himself heard. There was a note of panic in his voice.

‘Can you see that, John?’ he yelled, shutting off the steam and applying the brakes. ‘Can you see that?’

‘What?’ asked Heddle, peering hard through the swirling smoke. ‘All I can see is a clear line. Is there a problem?’

What the fireman could not see, he soon felt. Within a hundred yards, the wheels of the locomotive left the rails with an awesome thud and pulled the string of carriages behind it. Heddle and Pike were thrown sideways and had to hold on to the tender to steady themselves. Surging on and quite unable to check its momentum, the train miraculously stayed fairly upright as it ploughed a deep furrow in the ground and ripped up the track behind it with ridiculous ease. They had completely lost control. At that speed and on that gradient, it would take them the best part of a mile to stop. All they could do was to hang on tight.

Gibbering with fear, Heddle pointed ahead. A ballast train was puffing towards them on the adjacent line. They could both see the continuous firework display under its wheels as the brakes fought in vain to slow it down. A collision was inevitable. There was no escape. Pike’s immediate thought was for the safety of his young fireman. Turning to Heddle, he grabbed him by the shoulder.

‘Jump!’ he bellowed. ‘Jump while you can, John!’

‘This bloody train was supposed to be blessed!’ cried Heddle.

‘Jump off!’

Taking his advice, the fireman hurled himself from the footplate and rolled over and over in the grass before hitting his head on a small boulder and being knocked unconscious. Pike stayed where he was, like the captain of a doomed ship remaining on the bridge. As the two trains converged in a shower of sparks, he braced himself for the unavoidable crash. He was writhing with guilt, convinced that the accident was somehow his fault and that he had let his passengers down. Fearing that there would be many deaths and serious injuries, he was overwhelmed by remorse. A sense of helplessness intensified his anguish.

When the engines finally met, there was a deafening clash and the Brighton Express twisted and buckled, tipping its carriages on to the other line and producing a cacophony of screams, howls of pain and groans from the passengers. Both locomotives were toppled by the sheer force of the impact. The long procession of wagons behind the other engine leapt madly off the rails and broke up like matchwood, scattering their ballast far and wide in a vicious hailstorm of stone. It was a scene of utter devastation.

Somewhere beneath the engine he had driven with such pride and pleasure was Frank Pike, crushed to a pulp and wholly unaware of the catastrophe left behind him. His first ever run on the Brighton Express had also been his last.

CHAPTER TWO

Alerted by telegraph, Detective Inspector Robert Colbeck left his office in Scotland Yard at once and caught the first available train on the Brighton line. His companion, Detective Sergeant Victor Leeming, was not at all sure that they would be needed at the site of the accident.

‘We’ll only be in the way, Inspector,’ he said.

‘Not at all, Victor,’ argued Colbeck. ‘It’s important for us to see the full extent of the damage and to glean some idea of what might have caused the crash.’

‘That’s a job for the Railway Inspectorate. They’re trained in that sort of work. All that we’re trained to do is to catch criminals.’

‘Did it never occur to you that this accident may be a crime?’

‘There’s no proof of that, Inspector.’

‘And no evidence to the contrary, Victor. That’s why we must keep an open mind. Unfortunately, the telegraph gave us only the barest details but it was sent by the LB&SCR and made a specific request for our help.’

‘Your help,’ said Leeming with a sigh of resignation. ‘I’m not the Railway Detective. I hate trains. I distrust them and, from what we’ve heard about this latest disaster, I’ve every reason to do so.’

Leeming was a reluctant passenger, glancing nervously through the window as the train clattered into Reigate station and shuddered to a halt. Colbeck, on the other hand, had a deep affection for the railway system matched by a wide knowledge of its operation. As a result of his success in solving a daring train robbery and a series of related crimes, newspapers had christened him the Railway Detective and subsequent triumphs had reinforced his right to the nickname. Whenever there was a crisis on the line, the first person to whom railway companies turned was Robert Colbeck.

He knew why Leeming was so disaffected that evening. The sergeant was a married man with a wife he adored and two small children on whom he doted. Being parted from them for a night was always a trial to him and he sensed that that was about to happen. A train crash on the scale described would need careful investigation and it could not be completed in the failing light. He and Colbeck might well have to spend the night near the scene before continuing their enquiries on the following day.

After stopping at Horley station, the train set off again and soon entered the county of Sussex. More passengers alighted at Three Bridges station then they chugged on for over four miles until they reached Balcombe. Amid a hiss of steam, they came to a halt.

‘Out we get, Victor,’ said Colbeck, rising to his feet and reaching for his bag. ‘This is the end of the line.’

‘Thank heavens for that, sir!’

‘No down trains can go beyond this point. No up trains from Brighton can get beyond Hayward’s Heath. The timetable has been thrown into complete disarray by the accident.’

‘How do we get to the scene?’

‘We take a cab.’

‘I like the sound of that,’ said Leeming, brightening at once.

Colbeck opened the carriage door. ‘I thought you might.’

‘You know where you are with horses. They’re sensible animals. They don’t run into each other.’

‘Neither do trains, for the most part.’

They stepped on to the platform and made their way towards a waiting line of cabs. Mindful of the great disruption caused by the accident, the railway company had tried to lessen its impact by arranging for a fleet of hansom cabs to be hastened to Balcombe station. Passengers destined for Burgess Hill, Hassocks Gate or Brighton itself would be driven to Hayward’s Heath where a train awaited them. The detectives were going on a shorter journey.

‘That’s better,’ said Leeming, settling gratefully into the back of a cab as it moved away. ‘I feel safe now.’

‘My only concern is for the safety of the passengers on the Brighton Express,’ said Colbeck, worriedly. ‘The train was almost full. According to the telegraph, there have been some fatalities. The chances are that others may die of their injuries in due course.’

‘You know my opinion, Inspector. Railways are dangerous.’

‘That’s not borne out by the statistics, Victor. Millions of passengers travel by rail each year in complete safety. Of the accidents reported, the majority are relatively minor and involve no loss of life.’

‘What about the engine that exploded last year, Inspector?’

‘It was a regrettable but highly unusual incident.’

‘The driver and his fireman were blown to pieces.’

‘Yes, Victor,’ admitted Colbeck. ‘And so was an engine fitter.’

He remembered the tragedy only too well. A locomotive due to take an early train to Littlehampton had exploded inside the engine shed at Brighton. The building had been wrecked, paving stones had been uprooted and one wall of an adjacent omnibus station had been shaken to its foundations. The three men beside the locomotive had been blown apart. The head of the engine fitter had been discovered in the road outside and one of the driver’s legs was hurled two hundred yards before smashing through a window and ending up on the breakfast table of a boarding house.

‘The boiler burst,’ recalled Leeming, gloomily. ‘I read about it. This company has had a lot of accidents in the past.’

‘It was a tank engine that exploded,’ explained Colbeck, ‘and it had run over 90,000 miles without a problem. When it was built, however, its boiler plates were thinner than has now become standard. Over the years, they’d been patched up. Under extreme pressure, they finally gave way.’

‘What a horrible death!’

‘It’s a risk that railwaymen have to take, Victor. Boilers burst far more often in the early days of steam transport. There have been vast improvements since then.’

‘I’ve never known a horse blow up,’ said Leeming, pointedly.

‘Perhaps not but they have been known to bolt before now and overturn cabs or carts. Also, of course,’ Colbeck reminded him, ‘even the largest coach can only carry a limited number of passengers. When the London to Brighton line first opened, four trains pulled a string of carriages containing 2000 people – and they arrived at their destination without any mishap.’

‘What do you think happened in this case, Inspector?’

‘It’s too early to speculate.’

‘The telegraph said that two trains had collided head-on.’

‘One of them, fortunately, was carrying no passengers.’

‘We’re going to find the most terrible mess when we get there.’

‘Yes,’ said Colbeck, looking up at the sky. ‘And the light is fading fast. That will hamper rescue efforts.’

‘What exactly are we looking for?’

‘What we always look for, Victor – the truth.’

It was like the aftermath of a battle. Mangled iron and shattered wood were spread over a wide area. Bodies seemed to be littered everywhere. Some were being lifted onto stretchers while others were being examined then treated on the spot. Dozens of people were using shovels and bare hands as they tried to clear the wreckage from the parallel tracks. The listless air of the wounded was offset by the frenetic activity of the railway employees. Carts were waiting to carry more of the injured away.

By the time that Colbeck and Leeming arrived at the site, lanterns and torches had been lit to illumine the scene. A few bonfires had also been started, burning the wood from the fractured carriages and the ruined wagons. Having met in a fatal collision, the two locomotives lay on their sides like beached whales, badly distorted, deprived of all power and dignity as they waited for cranes to shift their carcases. A knot of anxious people had gathered around each iron corpse, men for whom the destruction of a locomotive was tantamount to a death in the family.

As they picked their way through the debris, the detectives presented a curious contrast. Colbeck, the unrivalled dandy of Scotland Yard, was a tall, handsome, elegant man who might have stepped out of a leading role on the stage. Leeming, however, was shorter, stockier, lumbering and decidedly ugly. While the inspector looked as if he had been born in a frock coat, cravat, well-cut trousers and a top hat, the sergeant seemed to have stolen similar clothing without quite knowing how to wear it properly.

They soon identified the man they had come to see. Captain Harvey Ridgeon was the Inspector General of Railways, a job that consisted largely of investigating accidents throughout the system. He was standing near the two locomotives, talking to one of the many railway policemen on duty. Colbeck was surprised to see how young he was for such an important role. Ridgeon’s predecessor had been a Lieutenant-Colonel who, in turn, had been preceded by a Major-General, both in their fifties and at the end of their military careers.

Ridgeon, however, was still in his thirties, a fresh-faced man of middle height with an almost boyish appearance. Yet he also possessed a soldier’s bearing and a quiet, natural, unforced authority. Like all inspector generals, he had come from the Corps of Royal Engineers and thus had a good understanding of how the railways were built, maintained and run. When the detectives reached him, he had just parted company with the railway policeman. Colbeck performed the introductions. Though he gave them a polite greeting, Ridgeon was less than pleased to see them.

‘It’s good to meet you at last, Inspector Colbeck,’ he said. ‘Your reputation goes before you. But I fail to see why you made the effort to get here. What we need are doctors, nurses and stretcher-bearers, not a couple of detectives, however distinguished their record.’

‘We were summoned by the company itself, Captain Ridgeon.’

‘Then you must feel free to look around – as long as you don’t impede the railway policemen. They can be very territorial.’

‘We’ve found that in the past, sir,’ noted Leeming.

‘I’ve had occasional difficulties with them myself.’

‘I have to admire the way you got here so promptly,’ observed Colbeck, weighing him up with a shrewd gaze. ‘I didn’t expect you to turn up before morning.’

‘This was a dire emergency,’ said Ridgeon, taking in the whole scene with a gesture, ‘and I reacted accordingly. As luck would have it, I was staying with friends in Worthing so I was able to respond quickly when the alarm was raised. Had I still been in Carlisle, where I investigated an accident at the start of the week, then it would have been a very different matter. Before that, I was in Newcastle.’

‘You’re very ubiquitous, Captain Ridgeon.’

‘I have to be, Inspector. Accidents occur all over the country.’

‘That’s my complaint,’ Leeming put in. ‘There are far too many of them. Step into a train and you put your life in peril.’

‘Part of my job is to eliminate peril,’ said Ridgeon. ‘I only have powers to inspect and advise but they are important functions. Each accident teaches us something. My officers and I make sure that the respective railway companies learn their lesson.’

‘Then why do accidents keep on happening?’ Leeming saw two men vainly trying to lift a section of a wrecked carriage. ‘Excuse me,’ he said, moving away. ‘Someone needs a helping hand.’

Taking off his coat, Leeming was soon lending his considerable strength to the two men. The timber was easily moved. Ridgeon and Colbeck watched as the sergeant started to clear away more debris.

‘We could have done with Sergeant Leeming’s assistance when the accident actually happened,’ said Ridgeon. ‘It was a case of all hands to the pumps then. Believe it or not, things are much better now. It was chaos when I first arrived. Those with the most serious injuries have all been taken away now.’

‘There still seem to be plenty of walking wounded,’ said Colbeck, looking around. ‘Who is that gentleman over there, for instance?’

He pointed towards a man in clerical garb whose hands and head were heavily bandaged yet who was helping an elderly woman to her feet. Having got her upright, he went off to console a man who was sitting on the grass and weeping copiously into a handkerchief.

‘That’s the Reverend Ezra Follis,’ explained Ridgeon. ‘He’s a remarkable fellow. He was injured in the crash but, as soon as he was bandaged up, he did his best to offer comfort wherever he could.’

‘He obviously has great resilience.’

‘He also has a strong stomach, Inspector Colbeck. When they hauled out the driver of the ballast train, he was in such a hideous condition that some people were promptly sick. That little clergyman is made of sterner stuff,’ Ridgeon went on with admiration. ‘He didn’t turn a hair. He threw a blanket over the remains then helped to lift them on to a cart, saying a prayer for the salvation of the man’s soul.’

‘How many fatalities have there been so far?’ asked Colbeck.

‘Six.’

Colbeck was surprised. ‘Is that all?’

‘Yes, Inspector,’ replied Ridgeon. ‘Given the circumstances, it’s a miracle. Mind you, some of the survivors have terrible injuries and are being treated in hospital. According to the Reverend Follis, the Brighton Express left the track and careered alongside it for a couple of minutes before hitting the other train.’

‘In other words, the passengers had time to brace themselves.’

‘Exactly.’

‘I must speak to the Reverend Follis myself.’

‘He’s an interesting character.’

‘I assume that the driver and fireman of both locomotives died in the crash,’ said Colbeck, sadly.

‘Those on the footplate of the ballast train were killed outright. The driver of the express must also be dead because he’s buried beneath his engine. Until a crane arrives, we can’t dig him out.’

‘What about his fireman?’

‘John Heddle was more fortunate,’ said Ridgeon. ‘He jumped from the footplate before the collision took place. He sustained a nasty head injury during the fall and was still very dazed when I spoke to him, but at least he survived and will be able to give us confirmation.’

‘Confirmation?’ echoed Colbeck.

‘Yes – of what actually happened. The general feeling among the passengers is that the express went too fast around a bend and jumped off the track. In short, the driver was at fault.’

‘That’s a rather hasty verdict to bring in, Captain Ridgeon. It’s very unfair to blame the driver before all the evidence has been gathered, especially as he’s not alive to defend himself.’

‘I’m not sure that he has a defence.’

‘There are recommended speeds for every stretch of the track.’

‘Everyone I’ve spoken to says the same thing,’ argued Ridgeon. ‘The speed was excessive. They were there, Inspector. These people were in the Brighton Express at the time.’

‘That’s precisely the reason I’d doubt their word,’ said Colbeck. ‘Oh, I’m sure they gave an honest opinion and I’m not criticising them in any way. But all the passengers have been through a terrible experience. They’ll be in a state of shock. You have to allow for a degree of exaggeration.’

‘I talk to survivors of accidents all the time,’ Ridgeon told him, eyes blazing, ‘and I know how to get the truth out of them. I won’t have you casting aspersions upon my methods.’

‘I’m not doing so, Captain Ridgeon.’

‘Well, it sounds to me as if you are.’

‘I’d merely point out that there are no bends of any significance on this stretch of line. Indeed, on the whole journey from London to Brighton, you won’t find dangerous curves or problematical gradients.’

Ridgeon stuck out a challenging chin. ‘Are you trying to teach me my job, Inspector?’

‘No, sir,’ said Colbeck, trying to smooth his ruffled feathers with an emollient smile. ‘I simply think that it would be unwise to rush to judgement when you’re not in full possession of the facts.’

‘I’ve garnered rather more of them than you.’

‘That’s not in dispute.’

‘Then have the grace to bow to my superior expertise.’

‘I’ll be interested to read your report,’ said Colbeck, meeting his stern gaze without flinching. ‘Meanwhile, I’d be grateful for the names of the two drivers and the fireman who died.’

‘Why?’ asked Ridgeon.

‘Because, over the years, I’ve become acquainted with many people who work on the railway,’ came the reply. ‘I’ve been summoned twice before by the LB&SCR and got to know a number of their staff.’

Ridgeon consulted the pad he was holding. ‘The driver of the ballast train was Edmund Liversedge and his fireman was Timothy Parke.’ He glanced up at Colbeck who shook his head. ‘The driver of the other locomotive, presumed dead, was in charge of the Brighton Express for the first time, another factor that I have to take into account. Inexperience on the footplate can be fatal.’

‘What was the man’s name, sir?’

‘Frank Pike.’ He saw Colbeck heave a sigh. ‘You know him?’

‘I knew him quite well at one time,’ said Colbeck, coming to a decision and taking a step backward. ‘If you’ll excuse us, Captain Ridgeon, the sergeant and I will get back to London at once. I’ll take upon myself the duty of informing Mrs Pike of the death of her husband. It’s the least I can do for her.’

‘There’s nothing to keep you here, Inspector. The investigation is in safe hands and will not need to involve the Detective Department in any shape or form.’ He flicked a hand. ‘Good day to you.’

‘Oh, we’ll be back first thing tomorrow,’ said Colbeck, resenting the curt dismissal. ‘I want to make a closer examination of the site.’ He gave a disarming smile. ‘You’ll be amazed how different things can look in daylight.’

CHAPTER THREE

The Round House was a vast and intricate structure of wrought iron and brick, built to accommodate the turntable used by trains belonging to the London and North Western Railway. Situated in Chalk Farm Road, it was always filled with clamour and action. Since its erection in 1847, it had attracted many visitors but few of them were female and fewer still were as handsome as Madeleine Andrews. In effect, she was a human turntable, making the head of every man there veer round sharply when she entered.

Many engine drivers had taken their young sons to view the interior of the Round House. Caleb Andrews, a short, wiry man whose fringe beard was speckled with grey, was the only one who had taken a daughter armed with a sketch pad. Taller than her father, Madeleine was an alert, intelligent, spirited young woman who had taken over the running of their Camden house when her mother died. Andrews was known at work for his acid tongue and trenchant opinions but his daughter had tamed him at home, coping easily with his shifting moods and taking the edge off his irascibility.

‘There you are, Maddy,’ he said, raising his voice over the din and making a sweeping gesture. ‘What do you think of it?’

She gave a shrug. ‘It’s magnificent,’ she agreed, running her eye over the interior. ‘It’s like an industrial cathedral. It’s even bigger than it looks from outside.’

‘Bigger and noisier – I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve driven on to that turntable. It must be hundreds.’

‘Do you think anyone would mind if I made a few sketches?’

‘They wouldn’t dare to mind,’ said Andrews, distributing a warning glare around the circle of railwaymen. ‘Any daughter of mine has special privileges.’

‘Does that mean I can stand on the footplate while an engine is being turned?’ she teased.

He laughed. ‘Even I can’t arrange that for you, Maddy.’

Fiercely proud of her, Andrews stood there with arms akimbo as she began her first quick sketch. Her interest in locomotives was not a casual one. Having discovered an artistic talent, Madeleine had developed it to the point where it had become a source of income. Prints of her railway scenes had been bought by several people. What she had never drawn before, however, was a turntable in action. That was why she had asked her father to take her to the Round House.

Aware of the attention she was getting, she kept her head down and worked swiftly. It was left to Andrews to explain what she was doing and to boast about her modest success as an artist. Any talent she possessed, he was keen to point out, must have been inherited from him. While he chatted to his friends, Madeleine was sketching the locomotive that had just been driven on to the turntable before being swung round so that it could leave frontward. A simple, necessary, mechanical action was carried out with relative ease then the locomotive left with a series of short, sharp puffs of smoke.

Madeleine’s pencil danced over the paper and she scribbled some notes beside each lightning sketch. When she turned her attention to the structure itself, she craned her neck to look up at the domed roof. It was inspiring. The fact that the whole place was bathed in evening shadows somehow made the scene more magical and evocative. She was so absorbed in her work that she did not notice the man who came into the building and spoke earnestly to her father. After his jocular conversation with the others, Andrews was now tense and concerned, plying the newcomer with questions until he had extracted every last detail from him.

On their walk home through the gathering gloom, Madeleine noticed the radical change in her father’s manner. Instead of talking incessantly, as he usually did, he lapsed into a brooding silence.

‘Is anything wrong, Father?’ she asked.

‘I’m afraid that it is.’

She was worried. ‘You’re not in trouble for taking me there, are you? I’d hate to think that I made things awkward for you.’

‘It’s nothing like that, Maddy,’ he told her with an affectionate squeeze of her arm. ‘In fact, it’s nothing whatsoever to do with the LNWR. While you were drawing in there, Nat Ruggles passed on some disturbing news to me. There’s been a bad accident.’

‘Where?’

‘On the Brighton line.’

‘What happened?’

‘According to Nat, there was a collision between two trains the other side of the Balcombe tunnel. I suppose the only consolation is that it happened in open country and not in the tunnel itself.’

‘Nor on the Ouse Viaduct,’ she noted.

‘That would have been a terrible calamity, Maddy. If the viaduct was destroyed in a crash, the line would be closed indefinitely. Nobody would be able to take an excursion train to the seaside,’ he pointed out. ‘As it is, there are bound to be deaths and serious injuries. The Brighton Express would have been going at a fair speed and you know how poor the braking system is.’ He showed a flash of temper. ‘All that those brainless engineers think about is making trains go faster and faster. It’s high time someone designed a means of stopping them.’

He fell silent again and Madeleine left him to his thoughts. She knew how upset he was at the news of any railway accidents. He was always uncomfortably reminded of how hazardous his own job was. Andrews had courted disaster on more than one occasion but always escaped it. There was a camaraderie among railwaymen that meant a tragedy on one line was mourned by every rival company. There was no gloating. With regard to the LB&SCR, Caleb Andrews had even more reason for alarm. He had many friends who worked for the company and feared that one or more of them had been involved.

When they reached the house, they let themselves in. Having met his daughter at the end of his day’s shift, Andrews was still in his working clothes. He removed his cap and slumped into a chair.

‘I’ll make some supper,’ offered Madeleine.

‘Not for me.’

‘You have to eat something, Father. You must be starving.’

‘I couldn’t touch a thing, Maddy,’ he said with a grimace. ‘I don’t think I’d be able to keep it down. Just leave me be, there’s a good girl. I have too many things on my mind.’

It was late evening when Robert Colbeck arrived at the house and he was pleased to see a light in the living room. After paying the cab driver and sending him on his way, he knocked on the door. When it was opened by Madeleine, she let out a spontaneous cry of delight.

‘Robert! What are you doing here?’

‘At the moment,’ he said with a warm smile, ‘I’m enjoying that look of surprise on your face.’ He gave her a token kiss. ‘I’m sorry to turn up on your doorstep so late, Madeleine.’

‘You’re welcome whatever time you come,’ she said, standing back so that he could step into the house. She closed the front door behind him. ‘It’s lovely to see you so unexpectedly.’

‘Good evening, Mr Andrews,’ he said, doffing his top hat.

Deep in thought, the engine driver did not even hear him.

‘You must excuse Father,’ said Madeleine in a whisper. ‘He’s been upset by news of an accident on the Brighton line. Let’s go on through to the kitchen, shall we?’

‘But it was the accident that brought me here,’ explained Colbeck. ‘As it happens, I’ve just returned from the site.’

‘What’s that?’ asked Andrews, hearing him this time and getting up instantly from his chair. ‘You know something about the crash?’

‘Yes, Mr Andrews.’

‘Tell me everything.’

‘Give Robert a proper greeting first,’ chided Madeleine.

‘This is important to me, Maddy.’

‘I appreciate that, Mr Andrews,’ said Colbeck, ‘and that’s why I came. If we could all sit down, I’ll be happy to give you the full details. I don’t think you should hear them standing up.’

‘Why not?’

‘Just do as Robert suggests, Father,’ said Madeleine.

‘Well?’ pressed Andrews as he resumed his seat.

Sitting on the sofa, Colbeck took a deep breath. ‘It was a head-on collision,’ he told them. ‘Six people were killed and dozens were badly injured.’

‘Do you know who was on the footplate at the time?’

‘Yes, Mr Andrews. The driver of the ballast train was Edmund Liversedge. His fireman was Timothy Parke.’

Andrews shook his head. ‘I don’t know either of them.’

‘Their families are being informed of their deaths, as we speak.’

‘What about the express?’

‘The fireman was the only survivor on the footplate. He managed to jump clear before the crash. His name is John Heddle.’

‘Heddle!’ repeated the other. ‘That little monkey. I remember him when he was a cleaner for the LNWR. He was always in trouble. In the end, he was sacked.’ He scratched his beard. ‘So he’s made something of himself, after all, has he? Good for him. I never thought John Heddle would become a fireman.’

‘What about the driver?’ said Madeleine.

‘It appears that he was killed instantly,’ said Colbeck.

After looking from one to the other, he lowered his voice. ‘I’m afraid that I have some distressing news for you. The driver was Frank Pike.’

Madeleine was shocked and her father turned white. Frank Pike was more than a friend of the family. Andrews had been seriously injured during the train robbery that had brought Robert Colbeck into his life. The fireman that day had been Frank Pike and Colbeck had been impressed by his loyalty and steadfastness. He had been even more impressed by Madeleine Andrews and what had begun as a meeting in disturbing circumstances had blossomed over the years into something far more than a mere friendship.

‘I felt that you ought to know as soon as possible,’ Colbeck went on. ‘It seemed to me that you and Madeleine might prefer to be there when I break the news to his wife. Mrs Pike is sure to be sitting at home, wondering why her husband has not come back from work. She’s going to need a lot of support.’

‘Then Rose will get it from us,’ promised Madeleine. ‘This will be a crushing blow. She was so proud when Frank became a driver.’

‘It’s the reason he left the LNWR,’ recalled Andrews, sorrowfully. ‘They refused to promote him. The only way he could be a driver was to move to another company so that’s what he did. Frank Pike was the best fireman I ever had,’ he said, wincing. ‘I’ll miss him dreadfully.’ His eyes flicked to Colbeck. ‘Do you know what caused the accident?’

‘No,’ replied the detective, ‘and I was very sceptical about the one theory that was put forward. It was suggested that the express train went too fast around a bend and came off the rails as a result. Is that the kind of thing you’d expect of Frank Pike?’

‘Not in a hundred years!’ said Andrews, red with anger. ‘Frank would always err on the side of safety. I should know – I taught him.’ He jumped up and struck a combative pose. ‘Who’s been spreading lies about him?’

‘It’s just a foolish idea starting to take root.’

‘It’s more than foolish – it’s an insult to Frank!’

‘Don’t shout, Father,’ said Madeleine, trying to calm him.

‘Isn’t it enough that the poor man has been killed doing his job?’ yelled Andrews. ‘Why do they have to blacken his name by claiming that the accident was his fault? It’s wrong, Maddy. It’s downright cruel, that’s what it is.’

‘I agree with you wholeheartedly, Mr Andrews,’ said Colbeck, ‘and I’m sure that Pike will be exonerated when the full truth is known. Meanwhile, however, I don’t believe you should let this idle speculation upset you and I strongly advise you against making any mention of it to his widow.’

‘That’s right,’ said Madeleine. ‘We must consider Rose’s feelings.’

‘Shall we all go there together? I know that she lives nearby.’

‘It’s only minutes away, Robert.’

‘This is a job for Maddy and me,’ announced Andrews, making an effort to control himself. ‘It was good of you to come, Inspector, and I’m very grateful. But I know Rose Pike well. She’ll be upset by the sight of a stranger. She’d much rather hear the news from friends.’

‘I accept that,’ said Colbeck.

‘Before we go, I’d like to hear more detail of what actually happened. Don’t worry,’ Andrews continued, holding up a palm, ‘I won’t pass any of it on to Rose. I just want to know whatever you can tell me about the accident. You don’t have to listen to this, Maddy,’ he said. ‘If it’s going to upset you, wait in the kitchen.’

‘I’ll stay here,’ she decided. ‘I want to hear everything.’

‘In that case,’ said Colbeck, weighing his words carefully, ‘I’ll tell you what we discovered when we got to the scene.’

Since he had been spared the ordeal of spending a night way from his family, Victor Leeming made no complaint about the early start. He and Colbeck were aboard a train that took them to Balcombe not long after dawn. It was a fine day and the sun was already painting the grass with gold. Watching the fields scud past, Leeming thought about the present he ought to buy for his wife’s forthcoming birthday, hoping that he would be able to spend some of the occasion with her instead of being sent away on police business. Colbeck was reading a newspaper bought at London Bridge station. As he read an account of the train crash, his jaw tightened.

‘Someone has been talking to Captain Ridgeon,’ he said.

The sergeant turned to him. ‘What’s that, Inspector?’

‘This report lays the blame squarely on the shoulders of Frank Pike. I just hope that his widow doesn’t read it.’

‘Isn’t it possible that the driver of the Brighton Express was at fault?’ suggested Leeming.

‘I think it highly unlikely, Victor.’

‘Why?’

‘Pike had an unblemished record,’ said Colbeck. ‘If there had been any doubts at all about his skill as an engine driver, he would never have been allowed to take charge of the Brighton Express.’

‘We all make mistakes from time to time, sir.’

‘I’m not convinced that a mistake was made in this case.’

‘How do you know that?’

‘I don’t,’ admitted Colbeck. ‘I’m working on instinct.’

‘Well,’ said Leeming, ‘for what it’s worth, my instinct tells me that we’re on a wild goose chase. In my view, we could be more usefully employed elsewhere. We should let the railway company do their job while we get on with ours.’

‘I think you’ll find that the two jobs may overlap.’

‘Is that what Captain Ridgeon told you?’

‘Far from it, Victor,’ said the other with a grim chuckle. ‘The inspector general inclined to your view that we have no business at all being there. It was a polite way of saying that we were treading on his toes.’

‘So why are we bothering to go back, sir?’

‘We need to find out the truth – and if that involves stamping hard on both of the captain’s feet, so be it. We must establish whether the crash was accidental or deliberate.’

‘How do we do that?’

‘In two obvious ways,’ said Colbeck. ‘First, we inspect the point at which the express actually left the track to see if there’s any sign of criminal intent. Second, we speak to John Heddle. He was on the footplate at the time so will be an invaluable witness.’

‘I wonder why the driver didn’t have the sense to jump off.’

‘We may never know, Victor.’

Transferring to a cab at Balcombe station, they spent the rest of the journey in a more leisurely way. When they reached the site of the accident, they saw that considerable changes had taken place. Passengers were no longer strewn across the grass and all the medical assistance had disappeared. Work had continued throughout the night to clear the line so that it could be repaired. Fires were still burning and timber from the wreckage was being tossed on to them. Hoisted upright by cranes, the two battered locomotives stood side by side like a pair of shamefaced drunkards facing a magistrate after a night of mayhem. The body of Frank Pike had been removed.

Picking a way through the vestigial debris, the detectives reached the track for the up trains and walked along it in the direction of Balcombe. Beside them was a deep channel that had been gouged out of the earth by the rampaging Brighton Express. The rails of the parallel track had been ripped up and bent out of shape.

‘You can see what happened,’ noted Colbeck. ‘One side of the train was running on bare earth while the wheels on the other side were bouncing over the sleepers.’

‘It must have been a very bumpy ride, sir.’

‘Yes, Victor. On the other hand, the ground did act as a primitive braking system, slowing the express down a little and lessening the force of impact. This long furrow saved lives.’

‘But not enough of them,’ said Leeming under his breath.

They strolled on for over a quarter of a mile before they came to the point where the train had first parted company with the track. Four men in frock coats and top hats were clustered around the spot. As the detectives approached, the youngest of the men broke away to exchange greetings with them. Captain Ridgeon forced a smile.

‘Your journey is in vain, gentlemen,’ he said. ‘As we suspected, the Brighton Express left the rails here. It is, you’ll observe, on the crown of a bend. The indications are that the train was travelling too fast to negotiate the bend properly.’

‘This is not what I’d call a real bend,’ said Colbeck, studying the broken rail then looking up the line beyond it. ‘It’s no more than a gentle curve. High speed would not have caused a derailment.’

‘Then what would have done so?’ challenged Ridgeon.

‘The most likely thing is an obstacle on the line.’

‘Where is it? We’d surely have found it by now. Besides, John Heddle, the fireman, would have noticed any obstacle in the path of the train and he swears that he saw nothing.’

‘I’d like to speak to Heddle myself.’

‘He’ll only tell you what he told us, Inspector. Nothing was blocking the line. We had an accident near here some years ago when a goods train hit a cow that had strayed on to the track. Since then, both sides have been fenced off.’

Colbeck was not listening to him. Crouching down, he ran a hand along the section of flat-bottomed, cast iron rail that had sprung away at an acute angle from the track. The section was curved but more or less intact. Colbeck stood up and gazed around.

‘What are you looking for, Inspector?’ asked Leeming.

‘The fishplates that held this rail in place,’ said Colbeck.

‘They would have been split apart when the train left the track,’ said Ridgeon, irritated by what he saw as the detective’s unwarranted interference. ‘It was going at high speed, remember.’