8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Capstone Classics

- Sprache: Englisch

DISCOVER ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT ACCOUNTS OF SLAVERY IN NINETEENTH CENTURY AMERICA

One of history’s greatest crimes, the American slave trade led to the suffering of untold numbers of men and women. But how can we better understand the lives and experiences of those who endured it?

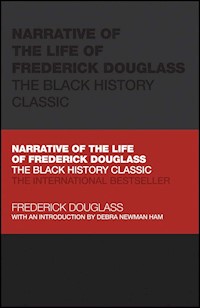

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass is a harrowing first hand look at the brutal indignities of slavery in the nineteenth century, and the society that allowed it to happen. To better understand our shared present, we need to fully grapple with our difficult past. Douglass’ Narrative is a key piece of that puzzle.

An insightful introduction by Debra Newman Ham, a former Black history archivist for the Library of Congress, analyzes the text and looks at the key events in Douglass’ life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 228

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

COVER

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

INTRODUCTION

EARLY LIFE

MERE CHATTEL

GLIMPSING ANOTHER WORLD

PLOTTING ESCAPE

FLEEING NORTH

WRITER AND SPEAKER

DOUGLASS AND CHRISTIANITY

LATER YEARS

FURTHER READING

ABOUT DEBRA NEWMAN HAM

ABOUT TOM BUTLER-BOWDON

PREFACE

LETTER FROM WENDELL PHILLIPS, ESQ.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

NOTE

11

NOTES

APPENDIX

A PARODY

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover Page

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

ii

iii

v

vi

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

xv

xvi

xvii

xviii

xix

xx

xxi

xxii

xxiii

xxiv

xxv

xxvii

xxix

xxxiii

xxxiv

xxxv

xxxvi

xxxvii

xxxviii

xxxix

xl

xli

xlii

xliii

xliv

xlv

xlvi

1

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

13

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

35

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

77

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

89

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

101

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

191

192

193

194

195

Also available in the same series:

Beyond Good and Evil: The Philosophy Classic by Friedrich Nietzsche (ISBN: 978-0-857-08848-2)

Meditations: The Philosophy Classic by Marcus Aurelius (ISBN 978-0-857-08846-8)

On the Origin of Species: The Science Classic by Charles Darwin (ISBN: 978-0-857-08847-5)

Tao Te Ching: The Ancient Classic by Lao Tzu (ISBN: 978-0-857-08311-1)

The Art of War: The Ancient Classic by Sun Tzu (ISBN: 978-0-857-08009-7)

The Game of Life and How to Play It: The Self-Help Classic by Florence Scovel Shinn (ISBN: 978-0-857-08840-6)

The Interpretation of Dreams: The Psychology Classic by Sigmund Freud (ISBN: 978-0-857-08844-4)

The Prince: The Original Classic by Niccolo Machiavelli (ISBN: 978-0-857-08078-3)

The Republic: The Influential Classic by Plato (ISBN: 978-0-857-08313-5)

The Science of Getting Rich: The Original Classic by Wallace Wattles (ISBN: 978-0-857-08008-0)

The Wealth of Nations: The Economics Classic by Adam Smith (ISBN: 978-0-857-08077-6)

Think and Grow Rich: The Original Classic by Napoleon Hill (ISBN: 978-1-906-46559-9)

The Prophet: The Spiritual Classic by Kahlil Gibran (ISBN: 978–0–857–08855-0)

Utopia: The Influential Classic by Thomas More (ISBN: 978-1-119-75438-1)

The Communist Manifesto: The Political Classic by Karl Marx and Friedich Engels (ISBN: 978-0-857-08876-5)

Letters from a Stoic: The Ancient Classic by Seneca (ISBN: 978-1-119-75135-9)

A Room of One's Own: The Feminist Classic by Virginia Woolf (ISBN: 978-0-857-08882-6)

Twelve Years a Slave: The Black History Classic by Solomon Northup (ISBN: 978-0-857-08906-9)

The Interesting Narrative of Olaudah Equiano: The Black History Classic by Olaudah Equiano (ISBN: 978-0-857-08913-7)

NARRATIVE OF THE LIFE OF FREDERICK DOUGLASS

The Black History Classic

FREDERICK DOUGLASS

With an Introduction byDEBRA NEWMAN HAM & TOM BUTLER-BOWDON

This edition first published 2021

Introduction copyright © 2021 Debra Newman Ham and Tom Butler-Bowdon

The material for this edition is based on the 1845 edition of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, published by The Anti-Slavery Office, Boston.

Registered office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is Available:

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 9780857089106 (hardback)

ISBN 9780857089120 (ePDF)

ISBN 9780857089113 (epub)

INTRODUCTION

By Debra Newman Ham & Tom Butler-Bowdon

As an ex-slave, orator, journalist and political organizer who challenged both slavery and institutional racism in America, Frederick Douglass was a seminal figure of the nineteenth century. He arguably did more than anyone to turn the country against the “peculiar institution”.

Douglass's Narrative is one of the first accounts of slavery by a fugitive slave. It is both a balanced first-hand insight into his own harrowing story, and a window into the common slavery practices in his time, including its destruction of family life, extreme poverty, absence of legal rights, and dearth of education.

Douglass was a mesmerizing speaker, and audiences could scarcely believe that his eloquent speeches came from a black man, let alone a former slave. But by setting down his account in writing, he would put to rest the doubts of many.

The separation, cruelty, neglect, injustice, and prevention of learning Douglass experienced would on the surface appear to be the recipe for all manner of physical and psychological disorders. The fact that Douglass emerged not only alive, but sane and prosperous, is testament to the power of the individual against overwhelming odds.

EARLY LIFE

Frederick Douglass was born at Holme Hill Farm near the Tuckahoe Creek in Talbot County, Maryland. He was owned by Captain Aaron Anthony. He begins the Narrative by saying he did not know his birthday, and that “by far the larger part of the slaves know as little about their ages as horses know of theirs.”

Slave owners separated mothers from children and placed them in different locations, to intentionally weaken familial bonds. Douglass says he only remembers seeing his mother four or five times when he was young. She would steal away from her master and spend the night with him, returning to her place of work before dawn. He notes in a later version of his autobiography that she referred to him as “my little Valentine,” leading him to speculate that he was born on February 14.

After hearing an owner say that he was sixteen years old, Frederick was able to compute his birth year to be 1817 or 1818. A later discovered birth record kept by Aaron Anthony (now held at the Maryland State Archives) confirms his birth year was 1818 and that his mother's name was Harriet Bailey. Frederick Bailey, as he was known for the first twenty years of his life (we will see how it changed to Douglass), was told that his father was a white man, possibly Anthony, although he was never able to confirm it.

The lack of clear information surrounding his birth and parentage would come to symbolize the abuse and lack of rights that came with being a slave. Slavery not only deprived Douglass of his mother but exposed him to cold, hunger and numerous other privations. He vividly describes the bloody whippings and shootings by his masters. The flogging and beating of his aunt, vividly described in the Narrative, was an event seared into his young mind.

MERE CHATTEL

So that his readers could begin to understand the system of “chattel” slavery, in the Narrative Douglass is careful to emphasize that the slave had no say in their living quarters or work assignments, no rights to family relationships, no redress for grievances and no legitimate testimony in the courts. A slave was legally considered to be property like a horse or a piece of household furniture, not a person. Chattel slavery means the slave as personal property, almost on the same scale as livestock.

Whites could not be prosecuted by slaves for crimes against them. Or as Douglass puts it, “No matter how innocent a slave might be – it availed him nothing …To be accused was to be convicted, and to be convicted was to be punished; the one always following the other with immutable certainty.”

In the event of grievances for cruelty or even murder, a slave could not even act as a witness. Killing a slave was not treated as a crime, either by the courts or by the community. Indeed, Douglass writes, “It was a common saying, even among little white boys, that it was worth a half-cent to kill a ‘nigger’, and a half-cent to bury one.”

GLIMPSING ANOTHER WORLD

In 1825, when he was six or seven years old, Frederick's owner selected him to leave the farm and work as a companion to a small child in a white family, the Aulds, in Baltimore. His mistress was kind at first and provided him with the rudiments of education alongside her son. But the education of slaves was taboo, and before long she was stopped by her husband.

This bar against learning to read made Frederick believe that it was all the more valuable. He had had a glimpse of a different life, one in which he could be educated. In the Narrative, he says he believes that the providential hand of God rescued him from rural slavery, which in many cases was a worse experience than city slavery. He believes that God brought him to Baltimore and let him hear the statement (from his white owner) that education would ruin a slave's acceptance of his or her lot in life. He sums up the view of slave owners: “if you teach that nigger … how to read, there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave. He would at once become unmanageable, and of no value to his master.”

Frederick would try to get his hands on books whenever he was alone in the house. He enlisted white neighborhood boys to help him learn, asking them to write words on sidewalks or fences so he could learn how to spell them. In return, he gave them pieces of bread because at the time he was well fed. One of the books the local boys made recitations from was The Columbian Orator, a collection of political essays and dialogues designed to inculcate civic values and patriotism in white American schoolchildren. Douglass obtained a copy of the book and studied the speeches with enjoyment. What stuck in his mind the most was a dialogue between a master and his slave. He also came across the word ‘abolition.’ He resolved to learn more about the abolitionist movement, and looked for ways to escape his life as a slave.

PLOTTING ESCAPE

Some years later, Frederick was sent to work with Baltimore shipbuilders on the docks and learned the trade of caulking (sealing) ships. All the time, he secretly memorized written instructions for ships’ construction. Socially, some doors to free black homes and African American churches began to be open to him.

But just as Frederick was beginning to see a path out of slavery, the death of his master meant that he had to return to the Talbot County property. A subsequent owner's death resulted in Douglass, now a teenager, being assigned to several farms doing work for which he had no training or experience. In an attempt to break his assumed resistance (which was, more probably, his ineptitude) to this new labor, Frederick was sent to a “slave breaker,” Edward Covey, whose job was to beat slaves into lifelong submission to their owners. The Narrative includes horrible descriptions of his time under Covey, but ultimately the breaker was unsuccessful. Douglass somehow kept his dignity, and his intelligence and skills seemed to mark him out for other things.

Douglass c. 1840, in his early twenties. Photographer unknown

Psychologically, Douglass felt that he emerged from these experiences a free man, although legally he was still enslaved. He was sent to several other locations to do farm labor, and his biggest complaint was that most of them did not provide enough food or even enough time to eat the little they were given. At one location he developed a group of friends who worked and worshipped with him. He taught them how to read and provided Sunday School lessons to those who were willing. This instruction was a great source of pride.

In 1833, the group hatched an unsuccessful plan to run away. After being jailed for a short time, Douglass was returned to his former Baltimore home, where he worked again on the docks. Eventually, he began hiring himself out and presenting his wages to his master and receiving a small percentage for himself. He developed a relationship with a free black woman, Anna Murray, who would become his wife. She helped him cultivate friendships with others in the African American community both at work and at church, and the pair began planning a free life together.

FLEEING NORTH

Douglass eventually got another chance in 1838. After an altercation with his owner about an unapproved absence at a religious camp meeting, he was even more determined to escape. With Anna's help, who provided him with a sailor's outfit and money for travel, he was able to board a train north and then take a steamboat to Pennsylvania, an anti-slavery city. From there he made it to a safe house in New York City belonging to black abolitionist David Ruggles.

Soon after, Murray joined Douglass in New York and the couple were married. They settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts, a whaling town that was also a center of abolitionist activity and where many former slaves had relocated. The couple were helped by Nathan Johnson, a successful businessman and abolitionist who had bought his freedom. To celebrate his liberty, Frederick (who was still known as Frederick Bailey) let Johnson choose a new last name for him. Johnson, who had been reading Walter Scott's poem The Lady of the Lake (which features characters from the Scottish Douglas family) suggested Douglass. The men may also have been thinking of Grace Douglass, a prominent African American abolitionist at the time.

Anna Murray Douglass c. 1860. Photographer unknown

The northern states had started the process of ending slavery during the American Revolution, so the practice no longer existed there. Nevertheless, racial prejudice and discrimination dominated social interaction between the races. In New Bedford, Douglass wanted to work as a ship caulker as he had in Maryland, but the white workers banned him because of his color. Douglass also found that white churches were not welcoming, so he joined the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and eventually became a licensed lay preacher, but was never ordained. His roles included church sexton, Sunday School superintendent, and steward. Adjusting to the new racial climate, Douglass was able to obtain regular work as a laborer on the docks.

He voraciously read newspapers but especially The Liberator, edited by abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and largely funded by free African Americans. Garrison and a small army of abolition orators and lecturers regularly spoke out against slavery.

WRITER AND SPEAKER

Douglass quietly began to attend antislavery meetings. Then, in 1841, spurred by the inaccurate, sometimes even ridiculous representations of Southern slavery, he spoke for the first time as a former slave and an eyewitness of numerous atrocities. Thus commenced his career, encouraged by Garrison and others, as an abolitionist orator.

As a tall, mahogany-skinned man with a resonant baritone voice and a lion's mane of hair, he was such an impressive speaker that his mostly white audiences found it unbelievable that he had ever been a slave at all. Because of the enforced ignorance of blacks, many whites assumed that slaves were not teachable. Pseudo-scientific ideas about race abounded, none of which were complimentary to descendants of Africa, free or enslaved.

Douglass went on a speaking tour around the Eastern and Midwestern states of America organized by the Anti-Slavery Society. At some events he was jostled and injured by defenders of slavery, and publicity led to threats of further harm and kidnapping.

Some slave narratives had been ghostwritten, so to prove his authenticity Douglass set out to write his Narrative entirely by his own hand. Published in Boston in 1845 by William Lloyd Garrison, its initial print run of 5,000 copies sold in four months, and further printings soon followed.

Douglass's champion, abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison. Engraving from 1879 newspaper

His first trip abroad, in 1845, was a two-year lecture tour of England and Ireland, where he was constantly amazed to be treated as an equal to white people. In My Bondage and My Freedom, he recalls:

I gaze around in vain for one who will question my equal humanity, claim me as his slave, or offer me an insult. I employ a cab – I am seated beside white people – I reach the hotel – I enter the same door – I am shown into the same parlour – I dine at the same table – and no one is offended … I find myself regarded and treated at every turn with the kindness and deference paid to white people. When I go to church, I am met by no upturned nose and scornful lip to tell me, ‘We don't allow niggers in here!’

The talks helped the Narrative become popular in Ireland and England, with five editions produced there between 1846 and 1847. After returning to America, he began publishing an abolitionist newspaper, The North Star. He also published a fictionalized account of a slave's life, The Heroic Slave (1852).

The expectation had been that Douglass would simply tell the story of what had happened to him, but as his reading became wider he began speaking and writing on matters of politics and political philosophy. He noted in a talk in New York in 1847, “I have no love for America, as such; I have no patriotism. I have no country. What country have I? The Institutions of this Country do not know me – do not recognize me as a man.”

The Narrative is the first of three autobiographical works, including My Bondage and My Freedom (1855) and Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1881, revised 1892). As well as a glowing preface by William Lloyd Garrison, it was endorsed by prominent abolitionist Wendell Phillips. All three autobiographies were bestsellers at home and abroad and were a significant source of income for Douglass.

The backlash to Narrative was considerable. Runaways like Douglass could be recaptured anytime. Owners published their slaves’ descriptions in newspapers and often offered generous rewards for their return. Secrecy was the byword for the fugitives. Nevertheless, Douglass wrote his autobiography revealing his past in detail. He provided particulars about the names and places of his owners, his birthplace, and his work on farms and in Baltimore City.

Douglass in his early thirties, after publication of the

Narrative

. Photograph by Samuel J. Miller

After he published the Narrative in his late twenties, he knew he was in danger of being recaptured. In 1846, he was able to secure funds from British abolitionists to formally purchase his freedom (at a cost of $711). Britain had passed the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833.

DOUGLASS AND CHRISTIANITY

A theme in the Narrative is Douglass's assessment of the behavior of whites who called themselves Christians and yet taught their slaves about the Bible and the teachings of Jesus Christ. This was also a theme in many of his antislavery speeches. Some preachers and owners tried to live out the teachings of the New Testament, but most simply took lines from the Bible out of context to justify slavery. Indeed, Douglass notes that the worst owners also seemed to be the most religious. He mentions the slave breaker who wanted to worship and sing with him during prayer meetings, and owners and overseers who were rich and pious but who whipped women until the blood ran from their bodies.

In highlighting the hypocrisy of those who would call themselves Christians, the Narrative reads as quite an anti-religious text. In the Appendix, however, Douglass attempts to distinguish between genuine and false Christians. In doing this, he was probably trying to appease his supporters, who were not plantation owners but city-dwelling Christians in the North-East. An excerpt from the Appendix gives both a sense of the oratorical style that made Douglass famous, and his views on religion:

What I have said respecting and against religion, I mean strictly to apply to the slaveholding religion of this land, and with no possible reference to Christianity proper; for, between the Christianity of this land, and the Christianity of Christ, I recognize the widest possible difference – so wide, that to receive the one as good, pure, and holy, is of necessity to reject the other as bad, corrupt, and wicked. To be the friend of the one, is of necessity to be the enemy of the other. I love the pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ: I therefore hate the corrupt, slaveholding, women-whipping, cradle-plundering, partial and hypocritical Christianity of this land.

LATER YEARS

During the fifty years following the publication of the Narrative, Douglass was a forthright advocate for human rights, and not only of black people. He and Anna provided a temporary home to hundreds of escaped slaves as part of the Underground Railroad. When slavery ended with the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, he regularly spoke out for the civil and voting rights that became enshrined in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

In the 1840s, on the abolition circuit, Douglass found that female abolitionists were not allowed to speak out publicly. This led him to become an outspoken proponent of women's emancipation. He was the only man to attend the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention in New York for women's rights, and told the audience that he could hardly agitate for black rights and keep quiet on female suffrage:

In this denial of the right to participate in government, not merely the degradation of woman and the perpetuation of a great injustice happens, but the maiming and repudiation of one-half of the moral and intellectual power of the government of the world.

In 1882, after over forty years of marriage, Anna died. Before long, though, Douglass married a white woman suffragist and abolitionist, Helen Pitts, who was about the age of his oldest daughter. Amid the controversy, Douglass said: “This proves I am impartial. My first wife was the color of my mother and the second, the color of my father.”

He was also an early campaigner for black children's education, and against the racial segregation of education. In the Civil War, he argued that black Americans should be able to fight on the Union side.

After Rutherford B. Hayes became president in 1876, Douglass was appointed marshal to the District of Columbia. It was the first ever Senate-approved posting of a high-level job to a black man and, although it involved few duties, provided a handsome stipend. In 1878, he was able to buy a 20-room home overlooking Washington D.C. “Cedar Hill” is now a federally run museum, the Frederick Douglass National Historic Site.

Douglass in mid-1880s with second wife Helen (sitting). Photographer unknown

Douglass and Helen travelled widely in the 1880s, including trips to Europe. He remained in demand as a speaker. He was opposed to the various ‘Back to Africa’ resettlement programs mooted at the time, and also the idea of black separatist movements and all-black towns.

In 1889, President Harrison appointed him the consul-general to the Republic of Haiti, which he resigned in 1891. The following year, Douglass built a row of rental houses for African Americans, which still stands in the Fells Point area of Baltimore.

Douglass died on February 20, 1895, having just returned from a women's rights meeting, where he had been escorted onto the stage by Susan B. Anthony.

His writings and speeches fill many volumes. He became revered by many, black and white, and was one of the most photographed Americans of the nineteenth century. Schools and buildings are named after him.

Douglass made an indelible impression on American life.

FURTHER READING

The Library of Congress is a rich source of Frederick Douglass's manuscripts and correspondence. Many of his earlier writings and papers were destroyed in an arson attack on his home in Rochester, New York, in 1872, but the LC collection still contains over 7,000 items and 38,000 images. Many of the materials are available online.

Collections of his works include John W. Blassingame, et al, The Frederick Douglass Papers, (3 vols., Yale University Press, 1979), and Frederick Douglass: Selected Speeches and Writings, (edited by Philip S. Foner, abridged and adapted by Yuval Taylor, 1999).

The most comprehensive modern biographies are William S. McFeely's Frederick Douglass (1991) and David W. Blight's Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (2018).