6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

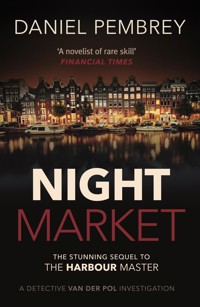

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

For fans of John Harvey's Charlie Resnick series and Michael Connelly's Harry Bosch,Night Marketis the second in the gripping Detective van de Pol investigation series. When Henk van der Pol is asked by the Justice Minister to infiltrate a team investigating an online child exploitation network, he can hardly say no - he's at the mercy of prominent government figures in The Hague. But he soon realises the case is far more complex than he was led to believe... Picking up from where The Harbour Master ended, this new investigation sees Detective van der Pol once again put his life on the line as he wades through the murky waters between right and wrong in his search for justice. Sometimes, to catch the bad guys, you have to think like one...

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

NIGHT MARKET

When Henk van der Pol is asked by the Justice Minister to infiltrate a team investigating an online child exploitation network, he can hardly say no – he’s at the mercy of prominent government figures in The Hague. But he soon realises the case is far more complex than he was led to believe… Picking up from where The Harbour Master ended, this new investigation sees Detective Van der Pol once again put his life on the line as he wades the murky waters between right and wrong in his search for justice.

Sometimes, to catch the bad guys, you have to think like on…

About the author

Daniel Pembrey grew up in Nottinghamshire beside Sherwood Forest. He studied history at Edinburgh University and received an MBA from INSEAD business school. Daniel then spent over a decade working in America and more recently Luxembourg, coming to rest in Amsterdam and London – dividing his time now between these two great maritime cities.

He is the author of the Henk van der Pol detective series and several short thriller stories, and he contributes articles to publications including The Financial Times,The Times and The Field. In order to write The Harbour Master, he spent several months living in the docklands area of East Amsterdam, counting De Druif bar as his local.

danielpembrey.com

Praise for The Harbour Master

‘Compelling and fast-moving […] The exquisitely drawn Inspector van der Pol battles his way to the truth in a way that his fictional ancestor, Inspector Piet van der Valk, created by Nicolas Freeling, did in the Sixties’ – Geoffrey Wansell, Daily Mail

‘Pembrey is a debut novelist of rare skill, marshalling his material with rigour and intelligence’ – Financial Times

‘Daniel Pembrey writes with great authority and authenticity. The Harbour Master is a compelling, highly believable tale set in the flesh markets of Amsterdam and the even seedier corridors of power beyond them, where it’s hard to know who the real criminals really are. You’ll keep turning these pages right till the end’ – Howard Linskey, author of Behind Dead Eyes

‘A splendid setting in what promises to be the start of a great new series’ – Ragnar Jonasson, author of the international bestselling Dark Iceland series

‘A vivid sense of place and a flawed and believable central character… could herald a great series and career from this new British author’ – Maxim Jakubowski, Lovereading

‘The Harbour Master is an accomplished novel, sporting a vividly realised sense of locale matched by an adroit evocation of character’ – Barry Forshaw, Brit Noir

‘The style of writing was so enjoyable…this really is an excellent read’ – Sarah Ward, author of A Deadly Thaw

‘Henk van der Pol makes for a great lead character – he’s strong willed, courageous and determined to unravel the cases he encounters and serve justice – no matter how complicated they might be…’ – Steph Broadribb, Crime Thriller Girl

‘The relationships linking Henk, his wife, and their daughter are flawlessly executed. Pembrey shows great skill as a crime fiction writer. His understanding and portrayal of people, places and situations is remarkable’ – DutchNews.nl

WE FIRST MEET HENK VAN DER POL IN THE HARBOUR MASTER WHICH CONTAINS PART I, II, AND III.

Part IV:

Night Market

1

IF YOU GAZE INTO THE ABYSS…

‘Don’t go in there.’

I was standing outside a set of double doors on the nineteenth floor of the Ministry for Security and Justice. The brown-carpeted anteroom was dim; much of it was in shadow. I’d been summoned for an after-hours meeting.

‘Not yet,’ the man added.

He was the assistant to the justice minister.

‘What’s this about, anyway?’ I asked.

‘I’m unable to advise,’ he replied, his dark features dimly lit by his computer screen. The soft clacking of his keyboard resumed.

I eyed my watch again. My wife was waiting back at our hotel to have dinner. Apparently, global-security considerations no longer respected office hours.

I paced over to the tall windows. It was dark outside and The Hague’s skyline winked, orange and white. The westward panorama took in the twin white towers of the International Criminal Court and, far ahead, I could make out the inky darkness of the North Sea… landmarks in the case of Rem Lottman, a kidnapped politician who’d been working for the energy minister, Muriel Crutzen. The case had brought me into contact with her, and she’d encouraged me to consider a job here in The Hague. I still didn’t know exactly what it involved, but perhaps I was about to find out.

I turned back to the assistant, about to say something, when the double doors to the ministerial office flew open and there he stood.

‘Henk,’ he said, appraising me. ‘Is it OK to call you Henk?’

‘Is it OK to call you Willem?’

He smiled and stepped forward, shaking my hand firmly.

Willem van der Steen was of medium height and a stocky build, with wiry grey hair. His white shirt was open at the neck; his sleeves were rolled up. He looked like he’d be a tough bastard in a fight.

He was a vote winner, ‘strong on law and order in uncertain times’. ‘We Dutch remain liberal – within limits’ was another of his election slogans. He was known to be a copper’s friend. He’d started off in the force and gone on to run Southern Regions. In some ways he’d remained an old-fashioned bruiser – but now he was one with formidable powers.

He released my hand and led me into his office. There was a pattern to the appearance of these ministers’ rooms, I was discovering: modern, workmanlike, unpretentious. In van der Steen’s case, I glimpsed an oil painting in the shadows: a marine vista, choppy seas. A ship sat in the centre, listing, valiantly holding its course.

There was a circular glass table strewn with papers. A phone sat in the middle.

‘A conference call ran long. The Americans like to keep us late.’

It begged questions that I couldn’t ask.

‘Drink?’ he asked, closing the door behind us.

The offer surprised me.

‘Still or sparkling?’ he added, correcting my misapprehension.

‘Still.’

He poured a glass for me, emptying a small bottle of water.

‘Please, take a seat.’

I sat on the opposite side of the table.

‘You come highly recommended,’ he said, emptying another bottle – sparkling – into his own glass.

‘Indeed?’

He sat down. ‘The energy minister.’

No surprises then… or none yet.

I waited for him to go on, struck by a tightening sensation in my chest – a wariness of what might be coming.

‘You’re over from Amsterdam?’ he asked. It was as if he were softening me up with small talk. He knew where I was from, surely.

‘Just for a few days.’

He studied his fingernails, which were slightly dirty. It looked like he might have been doing some gardening, and not quite managed to scrub away the soil.

‘What I’m about to tell you, I’m sharing in confidence. Is that understood?’

‘Of course.’

I wondered how much was in my file. Did it mention that my wife was a former features writer for Het Parool, the Amsterdam daily newspaper?

‘We’ve got a situation over in Driebergen.’

Driebergen, near Utrecht, was the headquarters of the old Korps Landelijke Politiediensten (KLPD) – the National Police Services Agency. The KLPD was now a unit within a single, newly merged Dutch police force. Not everyone had been happy with the unification. Office politics.

‘What kind of situation?’

‘There’s a specialist team over there which is investigating child exploitation. You may be aware of them?’

I stayed silent, but I knew about the team… more or less. They always seemed to be in flux, given changing police priorities and public perceptions.

‘It’s a six-person team,’ van der Steen went on. ‘It needs to grow, but before we grow it, we need to clean house.’

‘Oh?’ I took a sip of water.

‘We had a series of busts lined up. Mid-level members of what we’d managed to identify as a major paedophile network. The busts went bad.’

I noted how the minister used ‘we’ for what was being described as a tactical operation. The justice ministry oversaw the police of course, but van der Steen’s words implied an unusual level of involvement.

‘We now believe we’ve identified a kingpin in the same network,’ he went on. ‘In your neck of the woods, it turns out, Henk. We can’t risk an operational failure this time.’

‘You say the bust went bad… How?’

‘All the addresses had been hastily abandoned by the time the arrest teams arrived. Cleared of any computer material, cleaned almost forensically. Every single one.’

‘Addresses in Holland?’

‘Three of them, yes. The other addresses were in Belgium, Luxembourg and southern England.’

I gave a low whistle.

‘All recently vacated.’ His words reinforced the point.

‘A tip-off?’

‘Almost certainly, but by who… that’s the question.’

‘An insider – a plant?’

‘That’s one theory. A theory that needs proving or disproving, and fast.’

‘And you want me to look into it?’

His grey eyes held mine. They shone in the low light, like steel.

‘Why me?’ I asked, shifting in my seat.

‘Four reasons,’ he said, holding up the stubby fingers of one hand. ‘Evidently you’re a man with experience of life.’

I was fifty-six. ‘Thanks for reminding me.’

He smiled, briefly. ‘You’ve got an outsider’s perspective. At least, that’s what I’m told. Don’t underestimate the value of being able to sit outside the tribe and see what’s going on, in ways that others can’t.’

Funny – the energy minister had told me they needed me ‘inside the tent’ after the discoveries resulting from the Rem Lottman case. Now they wanted me back outside again – but under their supervision. Things evolve.

‘And as I said, you come highly recommended. We wouldn’t be having this conversation if you weren’t.’

I nodded impatiently. ‘That’s three reasons. You mentioned four.’

He locked eyes with me. ‘There’s no one else willing and able to do this, Henk.’

In my thirty-plus years as a policeman in Amsterdam, I’d seen a lot. But child abuse cases were known to be different. The images that the investigating teams had to look at each day, the victims’ stories they encountered… you can’t leave that stuff at the office, can’t go home and forget about it. It gets into your mind, your dreams.

‘If you take this assignment, it will change you,’ van der Steen warned.

‘Does that point to an alternate explanation?’ I said, stepping back from the precipice of the decision he’d asked me to make. ‘That someone on the team turned? Went native?’

Turned into a paedophile, in other words.

He shrugged. ‘That’s another possibility. These operatives have to stare at a lot of images. Perhaps, yes, it could… release certain things in certain men.’

He was looking at me searchingly.

‘I don’t pretend to understand what motivates older men to become interested in young children,’ he went on. ‘And let’s be clear about this. We’re talking about the sick stuff here, Henk. There’s a lot of it going on all of a sudden. As many as one in five of us may have leanings that way, one police psychologist in Leiden is now loudly proclaiming.’

I took a sip of water, wondering what response that hypothesis had got from the psychologist’s colleagues on the force.

‘There’s another point to consider – and I’m sure I don’t need to spell this out for you as a seasoned policeman. Investigating the investigators: it’s not for everyone.’

It contradicted the bond of loyalty among police personnel. I’d been in the army, which had the same ethos – though it was for reasons of survival there.

‘A plant, looking for a plant,’ I said meditatively.

He gave me a tight smile.

‘How would that work?’ I asked.

‘We’d get you a regular job on the team in Driebergen. You’d be one of the guys. But we’d also pair you with someone from the security services.’

‘A handler?’

‘You could put it that way, yes. We’d work on your cover – give you an alternative identity of sorts.’

‘My existing one’s not unblemished.’

‘I’d be suspicious if it was. You’re a human being.’

There was a crushing silence.

Sexual exploitation, trafficking, drugs, corruption, aggravated assault, homicide cases even – I’d worked them all, but the one area of policing I’d stayed away from was child abuse. Every cop felt in their heart the Friedrich Nietzsche quote: ‘Battle not with monsters, lest ye become a monster, and if you gaze into the abyss, the abyss gazes also into you…’

‘I also read about your altercation with the Amsterdam police commissioner.’

My old friend Joost. In abeyance since the Lottman case, but still there… still ready to cause problems in all areas of my professional and personal life.

‘Take this assignment, and that problem goes away.’

I didn’t doubt the justice minister’s ability to make it so.

‘And if I say no?’

He paused, choosing his next words carefully.

‘Then, like the others I’ve offered this assignment to, you’ll walk out of here. You’ll forget this conversation ever happened and, as agreed, you won’t mention it to anyone. In your case, Muriel will no doubt send you off to some other ministry. Somewhere easier. Environmental protection, maybe…’

I grimaced. ‘Just how important is this to the justice ministry?’

He leaned forward, pressing his palms onto the table. ‘I’d say it was vital… but that would be understating it.’ He paused for effect. ‘You can judge the decency of a society by how it treats its women and its children. If we’re not protecting our children, then what the hell are we doing?’

He was good, van der Steen. He knew what drove us. The real coppers that is, not the Joosts of the world.

‘It’s an unusual case,’ he continued. ‘Outwardly, it’s all supranational networks, technology, and collaboration with counterparts from other countries. In another sense, it’s a classic little locked-room mystery.’

‘How so?’

‘At least one of the six men – yes, they’re all men – in Driebergen is rotten. Your job, if you think you’re up to it, is to determine which, and to ensure that the rot stops there.’

I tried to visualise the airless environment I’d be entering, the smell of it – but couldn’t quite get there.

‘How do you know the insider is on that team?’

‘If you decide to proceed, you’ll see the file.’ He paused, and then asked with finality: ‘Is the mission clear?’

I found myself nodding slowly, and added a more emphatic nod.

‘Think about it,’ he concluded, sitting back again but still scrutinising me with those steely eyes. ‘Talk to your wife – in general terms – about a possible posting in Driebergen. You’re married?’ he asked, as if he might have misheard or misread something.

‘Yes.’

I eyed the painting over his shoulder. The ship, attempting to hold its course in the gathering storm, listing badly.

‘With a daughter,’ I added.

‘Then think it over.’ His lips twitched. ‘But not for too long.’

2

THE FILE

‘Driebergen?’ my wife asked, mouth agape.

‘Keep your voice down.’

‘Don’t tell me to be quiet, Henk. It’s not The Hague, nor Delft – like we agreed!’

‘No.’

‘What do you mean, no?’

‘No – you’re right.’

We were sitting in the bar of our hotel. The lighting was low; the room was full of flat, grey shapes and figures. I was tired of negotiating everything with everyone. Wasn’t life supposed to become easier as you neared retirement and cast off children and responsibilities? My life seemed to be going in the opposite direction.

I signalled to the barman for more drinks.

Petra clamped her hand over her cocktail glass, narrowly avoiding the candle flame as she did so. It guttered.

‘OK, one more drink.’ I corrected my order, raising my empty, sudsy glass.

‘But why Driebergen?’ Petra demanded.

‘Because it’s the headquarters of the old KLPD.’

‘I know that. I was a features writer once, remember?’

How could I forget? I felt like saying.

‘You were talking about a role with one of the ministries here,’ she said. ‘Why go there?’

‘Because the minister asked me to.’

A fresh Dubbel Bok arrived. Thank God.

Petra’s face was screwed up with incomprehension in the flickering light. As soon as the barman left she said, ‘Which minister?’

My voice was low. ‘The justice minister. It’s a confidential assignment. They’ve got a problem with one of the teams there, and that’s about all I can share.’

My wife had been a journalist for as long as I’d been a policeman. In putting up a ‘Do Not Enter’ sign, I might as well have confessed everything on the spot. It was just a matter of time.

But I was taking van der Steen’s warning seriously.

‘Well,’ Petra said, crossing her arms, ‘I’m not leaving Amsterdam without good reason.’

‘Last week you said that you couldn’t wait to get off the houseboat and be nearer Cecilia in Delft.’ Cecilia was her favourite cousin.

‘Oh, I’ll be getting off the houseboat all right,’ she said. ‘And finding dry land. In Amsterdam, close to our daughter.’

Our daughter Nadia wouldn’t be leaving the nation’s capital any time soon. Her social set could only countenance living in one Dutch population centre, and it certainly wasn’t Driebergen.

‘Should we get something to eat?’ I suggested. ‘It’s late.’

‘Too late.’ Petra sniffed. ‘I’m no longer hungry.’

I sighed exasperatedly, craning my neck. ‘Can I see a menu?’ I asked the barman.

‘We only do snacks. The restaurant, over there, serves food.’

‘Of course.’

We sat in silence.

Finally I said, ‘OK. I’ll tell you the mission I’ve been asked to undertake, but you mustn’t share it with anyone.’

‘As though I would!’

‘Anyone, Petra. Not Nadia… no one.’

‘Why would I share it with Nadia?’

‘You won’t.’ I paused. ‘And you must promise me that.’

‘Fine,’ she said.

‘Van der Steen wants me to look at the team investigating child abuse.’

Her eyes narrowed.

‘One of them is suspected of passing on police information to suspected paedophiles.’

Her head dropped.

‘They need to plug the leak.’

‘Why?’ she said, looking up again, her face screwed up in a silent wail. ‘Why this, of all the roles you could have taken?’

‘Because someone needs to do it.’

‘But why you?’

‘Would you rather I crossed the road?’

‘Oh, don’t do your lone-knight thing with me, Henk.’ Petra had her head in her hands.

She was right about most things, but not everything.

No one is.

‘Child abuse.’ She was mumbling. ‘There’s a reason child offenders live in mortal danger in prison and the rest of society –’

‘Well, maybe if there were more women on the team in Driebergen, things would be different.’ I was thinking about Liesbeth, a team member of mine who had a knack of winning trust and gaining insight into cases. She was the one who’d helped me break open the Lottman kidnapping case, with an early interview she’d done…

‘So it’s women to blame now, is it?’

‘That’s not what I’m saying. I’m just speculating that it’s not healthy to have an all-male team –’

‘Therefore, some unfortunate woman – or group of women – must now bear a further cost for these men’s depravities?’

Jesus, was this not difficult enough without turning it into a full-on gender war?

‘Looking at those images changes the neural pathways,’ she cried. ‘It rewires the brain!’

‘Please keep your voice down.’

She shook her head. ‘If it’s true of legal porn, it must be doubly so with this.’

I was about to challenge her on the pornography point but her words rang true. I thought again of those six men in the office in Driebergen…

‘I don’t want you looking at that stuff.’

‘All right.’

‘I’m serious, Henk. I don’t want that stuff in your head, and in our house, and in our bed!’

‘All right, dammit! Then I’ll make that the condition with van der Steen – I’m there to watch the watchers, but not to watch. Now, can we please get something to eat, before the restaurant shuts down and I shut down, too?’

*

At the justice ministry the following morning, van der Steen’s assistant led me into a small meeting room. A beige paper file marked Confidential sat on the polished wooden table.

‘You can’t take it away,’ he said.

It felt like an unnecessary piece of theatre – I had my smartphone with me, able to photograph anything inside the file.

‘In a few moments, someone from the AIVD will drop by to introduce himself.’ The Algemene Inlichtingen en Veiligheidsdienst is the Dutch secret service, charged with ‘identifying threats and risks to national security which are not immediately apparent’. It carries out operations at home and abroad, working with more than a hundred different organisations and employing over a thousand people – all of whom are sworn to secrecy about their work.

‘My handler?’ I clarified.

The assistant didn’t answer my question.

‘I’ll leave you to it,’ he said.

The door clicked shut behind him and I opened the file. There appeared to be two parts: a review of the operation van der Steen had mentioned (the bust that had been lined up and failed), and then an overview of the team in Driebergen, SVU X-19.

The nomenclature was familiar. ‘SVU’ stood for ‘Special Victims Unit’, the ‘X’ denoted that it didn’t appear as a matter of public record, and the ‘19’ distinguished it from other teams operating in that same capacity.

Conscious that I had little time before my handler arrived, I turned back to the beginning, scanning each page in turn. There are different ways to digest files but I like to avoid reading ahead, instead reliving the experience of the investigation – what was known at which point.

As I discovered, Operation Guardian Angel had grown out of a routine police check in Liège, Belgium. A Belgian police team had paid a house call to Jan Stamms, a convicted sex offender, to ensure that he was abiding by the terms of his early prison parole. They took a cursory look around Stamms’s suburban, semi-detached house, including his basement – where they heard a distant cry. The lead officer assumed that the cry had come from the neighbouring property.

Luck (or its absence) can come in many forms in police work, and in this case it was a throwaway remark by the lead officer’s partner, Veronique Deschamps, to the neighbour, who happened to be out in her front garden: ‘That’s quite a pair of lungs someone in your household has,’ Deschamps reported commenting.

‘But I live alone,’ the neighbour replied, perplexed.

Veronique Deschamps then insisted on a more thorough search of Stamms’s property. The first team still missed the sealed-up door in the basement, so good had Stamms’s handiwork been, but his clear nervousness prompted them to persist and bring in search dogs, which quickly found the location of a passage down to a second basement.

In the concealed chamber were two four-year-old boys, a basic latrine, cameras and lighting equipment… plus a computer with editing software and thousands of hours of video footage. The room also contained a set of workmen’s tools.

The twin boys required immediate medical attention. The video footage was too distressing for the local police team to review. However, by interviewing Stamms over a thirty-six-hour period, they elicited a confession to the existence of a video-sharing venue on the Dark Web called ‘Night Market’.

I found myself nodding admiringly as I read the report. The Liège team had covered an impressive amount of ground before handing over the case to the Belgian Federal Police, who in turn discovered that Stamms had tried to resolve a payment problem with a bank in Amsterdam. The Federal Police speculated that the payment he’d expected to receive there was in exchange for his supply of video footage. A growing belief that the network was centred in Holland caused overall control to pass to Driebergen.

The door opened and the assistant asked, ‘Do you want a drink, by the way?’

I blinked in consternation. ‘No. How much longer do I have?’

‘A few minutes.’

‘Who is my handler, anyway?’

‘His name’s Rijnsburger. You’ll meet him soon enough.’

The name didn’t mean anything to me. I waited in silence for the assistant to leave again, returning immediately to the file. There was a lengthy section on the build-up to the arrest teams going into the various different locations to apprehend the mid-level suspects already mentioned by van der Steen…

I wanted to take in all the details. But more than that, I needed to get to the section on SVU X-19 itself. Van der Steen had suspected that the leak (resulting in the failure of the arrests) had come from SVU X-19 – only why?

If you decide to proceed, you’ll see the file…

I flicked forward, thinking that there must be an elaborate Joint Investigation Team, with investigators from the various countries involved. Any one of them or their immediate colleagues could have had access to information about Operation Guardian Angel, and leaked it…

Aware that Rijnsburger might walk in at any moment, I skipped to the final section. Dumbstruck, I took in each of the SVU X-19 team members’ short bios and photos in turn.

Manfred Boomkamp was a twenty-year KLPD veteran.

Jacques Rahm was from Luxembourg’s Police Grand-Ducale.

Tommy Franks, formerly with the London Metropolitan Police’s Flying Squad, was on secondment from the UK’s national Child Exploitation and Online Protection agency.

Ivo Vermeulen represented the Belgian Federal Police.

And there was a fifth nationality involved: Gunther Engelhart was from Germany’s Bundeskriminalamt.

SVU X-19 was the Joint Investigation Team. They’d built a mini states-of-Europe in Driebergen.

I sat back, and exhaled hard. Was it some kind of experiment? Did they believe that it would be more efficient to centralise the joint investigative work? Had the rationale been to avoid precisely the kind of intelligence failure that had then occurred?

And what of my ability to take on these men?

I leaned forward again, reaching into my inside pocket for my phone, when there came a rap at the door. It swung open to reveal a tall, white-haired man in a tailored navy suit. He was rheumy-eyed.

‘Henk van der Pol?’

I didn’t deny it.

‘My name’s Wim Rijnsburger, I believe the minister has mentioned me. We’ll be joined by a psychologist shortly. Please, come this way.’

3

THREE DAYS LATER

It was an overcast morning as I approached the main entrance to the low building situated beside the busy A12. Only when I pulled into the car park did I appreciate how much Driebergen was otherwise surrounded by forest – the kind of dense forest that you no longer expect to find in central Holland. At some level, the location symbolised separation from the newly combined national police force headquartered in The Hague.

I still had a few minutes to spare before I was due to meet with Manfred Boomkamp, the commander of SVU X-19, so I locked up the car and reached for my cigarettes and lighter. My phone reception had dropped to a single bar of coverage.

I got a Marlboro Red going, reflecting on the last few days: the surprisingly small change to my identity required for me to assume the role here; the questions from the police psychologist that I never wanted to hear again…

A man to my right was trying to get his cigarette lit with matches. I recognised him as Tommy Franks, the English member of SVU X-19. His brown eyes were lively, fox-like. He had fine, sandy-coloured hair and a curiously old-fashioned, thick moustache.

I offered him a light.

‘Haven’t seen you before,’ he said, exhaling his first draw.

It felt prudent to reveal nothing about my posting at this point. ‘I’m here for a short while. Henk, by the way. And you?’

‘Tommy. The same – here for a spell.’

We stood in that spirit of temporary camaraderie afforded by smoking areas.

With his free hand, Franks stroked the tips of his moustache like a pet. I looked away from him, surveying the car park. ‘There are some nice cars here.’

‘There are,’ he agreed.

I was eyeing a midnight-blue BMW 3-Series convertible in particular. The plates were German, temporary.

‘It’s mine,’ he said.

Perhaps he was awaiting a reaction. He didn’t get one.

‘Damn sight cheaper over here than in the UK,’ he added, maybe reading my thoughts. He had the veneer of a well-spoken Englishman, but I could detect a regional British accent beneath. I couldn’t tell which.

‘Better get back to it,’ he said, discarding his half-finished cigarette.

‘Nice to meet you.’

‘See you around.’

*

I picked up my security pass at the front desk, and a receptionist escorted me to Manfred Boomkamp’s office. The open workspaces I saw on the way were like any others in the police realm: functional, sparsely furnished, and adhering to a ‘clean desk’ policy – no personal items left out.

Boomkamp had his own office, which had permitted him to hang a framed photo showing two grinning girls on pushbikes. The girls looked to be in their early teens. Boomkamp himself was clean-cut and angular-faced. He had silvery-blond hair and disconcertingly blue eyes. As I approached his desk, he uncoiled himself from behind it. He was one of the taller Dutchmen I’d met, and that was saying something.

‘Welcome, Henk. Sit down.’ A file was on the desk in front of him. Mine, almost certainly. ‘How are you settling into the area?’

‘Fine, thanks. I’m staying for a few days at the motel until I find something more permanent.’

I didn’t need to name the motel – there was only one in Driebergen.

‘Has your wife joined you yet?’

‘Not yet.’

‘Let me know if we can help. I’m sure my own better half, Mariella, could show’ – he paused, glancing at my file – ‘Petra around. Driebergen’s not everyone’s cup of tea, but it grows on you. The forest here can be quite lovely in spring.’

‘I’m sure.’

I didn’t know whether Boomkamp had been informed of my real mission here. The AIVD had told me to reveal only that I was an internal transfer, further to my job disappearing in Amsterdam. Effectively it was true – things with my former boss, Joost, had ended in a debilitating stalemate. And yet the guilt of my deceit was already starting to grow.

‘We need to get you operational as soon as possible.’ Boomkamp eyed his watch. ‘Helpfully, we have our weekly team meeting at eleven hundred hours. I’m going to have you shadow one of the other men.’

‘Which one?’

‘Ivo Vermeulen. He’s a specialist in technical analysis, which – with child exploitation – usually constitutes the heart of the investigation.’

I digested this information. Vermeulen was from the Belgian Federal Police, so would have been closest to the events in Liège that had launched the ailing Operation Guardian Angel.

‘Ivo’s a good man,’ Boomkamp added, ‘but he’s busy. We all are. We’re behind with our targets.’ He gave a tight smile. There were lots of tight smiles going around all of a sudden. ‘We don’t have enough men, even with your arrival.’ Then, almost as an afterthought: ‘It didn’t need to be this way.’

Perhaps he was referring to the merger between the KLPD and the national police force.

‘But,’ he conceded, ‘we all have marching orders.’

There was a pause in the conversation.

The experience of coming to this remote location in the forest, and of being among such a group of men – even the terminology used by Boomkamp: it was like rejoining the army.

I asked, ‘Were you by any chance in the forces?’

‘Do I give off that impression?’ He laughed. ‘In fact, three of the men here were. I’ll let you find out which.’

‘D’you mind telling me who does what?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Roles.’ The way army teams are put together, each man has a different, complementary area of expertise.

Boomkamp swivelled his chair from side to side. ‘Like I said, Ivo handles technical analysis. Gunther Engelhart specialises in technical surveillance, which is similar but different. Tommy Franks is more versed in traditional forms of surveillance. Similar, but different again. Whereas Jacques Rahm is into suspect psychology. The psychology of suspects, I should clarify.’

‘Similar but different?’

‘Definitely different. Rahm’s work I don’t pretend to understand so well. But apparently we need it.’

‘Marching orders?’

‘Marching orders.’

There was no mention of leaks, or of suspects being tipped off.

He held me with his stare. Just like the justice minister had.

Then I remembered something else from my meeting with the justice minister.

‘I thought this was a six-person team?’ I’d counted five, including Boomkamp.

‘It’s six now. Question being what your role here turns out to be.’

‘Can I ask,’ I said, deflecting his remark, ‘whose idea it was to staff the team from different countries?’

But before he had a chance to answer, there was a sharp rap at the door.

‘Enter,’ he said.

A fleshy face appeared round the doorjamb.

‘What is it, Engelhart?’

The German’s small, dark pupils flicked my way. ‘We’re all ready in the meeting room.’

‘I’ll be there in a minute.’ The door closed and Boomkamp sighed, then said, ‘Put the other men at ease, would you, Henk? Go out for a drink with them or something. They’re curious about you, and there’s only so much I can tell them. You came here highly recommended.’

It was a police euphemism; he was conceding that he’d been instructed to take me. Or was he maintaining a clever cover of his own?

*

The weekly meeting took place in a typical briefing room, brightly lit and smelling of institutional cleaning products. Seated around the long table were the two men I’d already met – Engelhart and Franks, the latter man’s eyes widening as he recognised me from the smoking area – plus two others.

Ivo Vermeulen was sitting on the near side of the table, and he turned to shake my hand. He had severe features and wore polished, ankle-high boots. Like Boomkamp, he had the air of a former military man.

Jacques Rahm was slight and olive-skinned. He wore a black polo neck, and a pancake holster that emphasised his stooped shoulders.

Boomkamp looped his jacket over a chair at the head of the table and gestured for me to sit. ‘Let’s get started,’ he began in English. ‘Joining us is Henk van der Pol, on secondment from the Amsterdam police force. Henk’s a thirty-year police veteran who’s seen the full range of action. Make him welcome.’

There was a smattering of hellos.

‘What will your role here be?’ Franks asked me directly.

‘Good to meet you again –’

Boomkamp answered. ‘He’s a general bandwidth-extender, if I can call him that.’

‘Around here,’ Rahm said with a sardonic smile, ‘it’s more dial-up than broadband, let me warn you.’

No one laughed.

‘Henk will help out with a bit of everything,’ Boomkamp explained tersely, ‘which will also allow him to get up to speed. Ivo, show him the ropes.’

Vermeulen shifted his stare from Boomkamp to me. I could only wonder what horrific images his grey irises had taken in.

There were some housekeeping points about schedules and holidays, then Boomkamp got down to business.

‘So where are we with the Karremans case?’

A silence pressed down on the room.

Finally, Franks spoke. ‘Why don’t we get the new boy’s perspective?’

Boomkamp looked from him to me. ‘OK, why not? Ivo?’

Vermeulen thwackeda couple of keys on his laptop – a sturdy model favoured by the old KLPD – then spun it round. ‘Tell us what you make of this.’

The screen was split crosswise, showing four images. I winced at what was going on in the foregrounds of each.

‘What am I looking for?’

‘The identifiers.’ It was Engelhart, the German, who spoke.

My eyes searched the four photos, trying desperately to block out what was being done to the child.

Trying to channel my three decades of investigative experience, my mind went to the case of Robert M, dubbed ‘The Monster of Riga’ by the media. Robert M was a Latvian man who had worked as a babysitter and day-care helper in Amsterdam. He’d abused at least eighty babies, filming or photographing his acts. The exact number was unknown because many parents refused to become involved in the investigation, preferring privacy for their children instead.

Robert M’s oversight had been to leave a toy with one baby. The toy was a Miffy, originally made in Holland. This narrowed the international search triggered by the discovery of the images online. A modified version of the Miffy photo was shown on the Dutch TV show Opsporing verzocht (Detection Requested), inviting members of the public to call in if one of them recognised the baby. An elderly man called, identifying the child as his grandson. The grandfather could easily have taken the matter up quietly with the father instead, or stayed silent – or indeed never have watched the show in the first place, in which case Robert Mikelsons might still be at it.

The case shocked Holland for many reasons, not least the revelation that Mikelsons – by now a Dutch citizen – had previously been banned from working in German day-care centres.

That information had never been disseminated.

‘The pattern…’ Gunther Engelhart prompted me.

Paedophiles operating at any level are by necessity expert dissemblers, but there will always be habits, blind spots… things so familiar that they might go unnoticed – become part of the furniture, even.

‘The window fenestration,’ I said. It was a metal design that mixed an industrial aesthetic with a faintly art deco style. ‘It’s distinctive, and it’s the same. It’s the same built environment – where the suspect feels comfortable.’

Vermeulen nodded approvingly. ‘He’s a natural.’

‘Wait,’ I said, stunned. ‘Which Karremans are we talking about?’

‘That Karremans,’ Boomkamp confirmed.

Van der Steen had mentioned a kingpin in my ‘neck of the woods’, only… ‘Heinrich Karremans – the Rijksbouwmeester? I find that hard to believe,’ I uttered.

‘Welcome to the big leagues,’ one of the men said.

There’s no exact translation for the Dutch title Rijksbouwmeester, the closest thing being ‘State Architect’. Heinrich Karremans happened to have played a key role in redeveloping the Amsterdam docklands, which I’d lived in since the 80s. His designs had created the physical backdrop to my adult life.

‘Why do you find it hard to believe?’ Vermeulen challenged.

‘I’m just testing your assumptions here,’ I said, still rocked by this turn of events. ‘Granted, several of Karremans’s buildings appear in these photos… but could it be somebody else using them?’

If true, why hadn’t the justice minister or Rijnsburger briefed me about this?

Jacques Rahm answered my question. ‘There is a psychologique concept called confirmation theory, in which subjects seek to integrate the abnormal events of their lives into a coherent narrative, by making troubling events feel normal…’

‘Meaning?’ I said sharply.

‘Abused people are predisposed to go on and abuse others. They wish to perceive the behaviour as ordinary – quotidien. And if the activity takes place in a familiar environment… tant mieux.’

‘Apologist,’ Gunther Engelhart mumbled under his breath.

Rahm looked genuinely shocked by the accusation.

‘Do you even know that Karremans himself was abused?’ I asked.

‘It’s a theory,’ Rahm replied.

‘Forget the theory,’ snapped Ivo Vermeulen. ‘The metadata of the images links them to Karremans’s IP address.’

I couldn’t ask whether the link was via the Night Market site – I hadn’t been told by the team about that yet – but it seemed a reasonable assumption. Only, something was missing.