Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

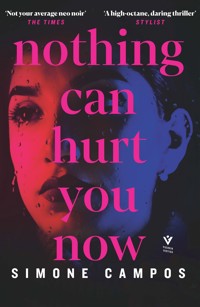

- Herausgeber: Pushkin Vertigo

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

Lucinda has lived her whole life in the shadow of herglamorous and outgoing model sister, Viviana. But when Viviana suddenly disappears on a trip to São Paulo, Lucinda discovers her sister's secret life - a thriving career as a highend sex worker. Convinced that someone on her sister's client list is responsible, Lucinda unites with Viviana's girlfriend, Graziane, and they set out to uncover the truth.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 277

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

‘Surprises, seduces and distresses us. The result is a novel of great force and narrative tension’

CAROLA SAAVEDRA, AUTHOR OF BLUE FLOWERS

‘Tightly tied suspense… striking female characters’

ESTADO DE MINAS

‘Unpredictable, feminist and political… the reader will reach the last paragraph hungry for more’

ROENDO LIVROS (BLOG)

‘Simone Campos offers us a strong novel with an engaging and agile narrative’

MARTHA BATALHA, AUTHOR OFTHE INVISIBLE LIFE OF EURIDICE GUSMAO

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

The billboard on the newspaper stand advertising the best Wi-Fi in Brazil seemed to bear no relation to the woman illustrating it, with her beaming smile and milky-white skin. She was smiling at the horizon, wearing a dainty white blouse, and looked like she was about to start talking. Lucinda imagined the snap being generated almost by chance during a change of pose at the shoot, as the model moved from a three-quarter profile to almost full-frontal. The photographer must have pointed over to where she should be looking – into eternity; she had obeyed and voila, the perfect photo, to be chosen from a multitude of others in which a thousand other girls in a thousand other nearly perfect poses would be passed over after test shoots of them standing next to the advertisement text.

Lucinda’s attention was drawn to the corner of the image – outside it. At the edge of the stand, half-hidden by a strategically placed lamp post, a very pale young girl with brown hair and glasses was vigorously rubbing her face. Lucinda quickly realised that the girl was not alone and that she was rubbing her face in protest at the kiss her tall, slim, brown-skinned boyfriend had just planted on her nose. Her nose! The nerve! But her protests seemed to be in vain: the boy was determined to kiss unorthodox parts of her face in public and was now laying into her cheek – licking it! – before immediately returning to the nose.

What… am I looking at? thought Lucinda, accelerating as soon as the lights changed. She couldn’t get delayed here; she had to get to that isolated point in the middle of the highway as fast as possible. Perhaps in doing so she would find her sister.

Viviana was not the woman in the advert. The woman in the advert was white and a redhead; her sister, like her, was mestizo: straight black hair, Indigenous features, coppery-golden skin. She got her bronzed tone from sunbathing at her building’s pool or country club; she didn’t like beaches. Lucinda spent all day in the office or at the studio, feeding off artificial light.

Her sister was in advertisements, but not the kind that appear on billboards, or on TV, or any other high-end media. She had seen her sister on the back of a bus and in a local newspaper; she frequently adorned web portals and occasionally also dentists’ brochures (‘Your smile is your calling card!’).

Anyone who asked Viviana ‘What do you do?’ would be unable to tell from the casual way in which she replied ‘Model’ that there was even the slightest hint of frustration with the fact that her face was considered perfectly fine for illustrating materials on the sex lives of modern couples, healthy food and the latest fashion trends, but not for selling nationwide broadband, like the redhead from the billboard. And it never, ever got her a speaking part in a commercial, let alone a spot on the catwalk.

It hadn’t always been that way.

• • •

Every afternoon Viviana (12) and Lucinda (16) would study French together at the language academy. The English they learnt at school was good enough, they didn’t need any extra practice. The school they went to, private and highly esteemed, was obsessed with the word ‘solidarity’ and was always organising events, group assignments and giveaways based around that theme. A while later, this motto would be forgotten and replaced with ‘entrepreneurship’, a fitting ideal for the new millennium, to be coveted by every student who wanted to achieve something in life. Before these two the slogan had been ‘One Earth’.

It was 1998. People still bought CDs, and they were all too familiar with the unique pain under the fingernails from trying to tear off the antitheft labels stuck to the packaging. It was also common knowledge that the batteries in a Discman always wore out before the CD playing inside it. Whenever the sisters were in the car together Viviana would use good behaviour to bribe her mother into letting her choose the radio station, which would invariably be playing ‘How Bizarre’ or ‘Macarena’. That’s right: everyone – children, teenagers and adults – listened to the radio, not only in the car but also at home; and some people, generally older ones, still listened to Voice of Brazil every day. Suits listened to live business news, the traffic updates during rush hour and the football on Sundays. Poorer people listened to baile funk on Imprensa FM if they were young, 98 FM if they were romantics and Copacabana if they were evangelicals. That was how you heard new music, stayed informed, felt part of a community of people who couldn’t always access the remote or didn’t have a second TV at home. It was important.

On that occasion the Spice Girls were playing, and Viviana was singing along quietly in the back seat of the car, symbolically holding her Discman for effect. Lucinda, who was riding in the front with their mother, said:

‘I’m not going to French wearing make-up.’

‘Lucy, wash your face and go.’

‘But I don’t know what kind of gunk they’ll put on my hair, it’ll be all gross… Anyway, I’ll be shattered.’

Cássia almost smiled as she repeated her daughter’s words:

‘Shattered…’

They arrived at the studio. Cássia began to deploy her perfect parallel parking. Lucinda was tense, her body frozen stiff in her seat, her hands touching the space beneath her knees. Looking backwards as she completed the manoeuvre, Cássia said:

‘OK, I’ve got to get to the court now. Vivi will stay with you, Lucy, and when you’re done, page me. And order a cab back. No buses.’

Lucinda nodded and pressed her lips together, looking straight ahead:

‘OK.’

Viviana showed no reaction. She asked for some money to buy a Mupy soya drink at the bakery opposite and was given it.

The sisters went up in the lift. In the lobby a pretty blonde girl, probably from the talent agency and already in full make-up, was sitting on a bench, awaiting her turn. A pale, nervous-looking boy had just come out, shaking out the shirt that was glued to his thin frame.

They separated without a word, Vivi sitting in the nearest seat to the exit while Lucinda was greeted by the producer.

‘Good morning,’ he said, checking his clipboard. ‘Lu-cin-da, right? My name’s Renato, I’m the producer here at French Connection, how are you? Have you brought your signed permission form? Excellent. Wait here, please. Your name will be called soon, OK?’

Lucinda sat down, waited for a while and was called. She noticed that the foundation she was about to put on had to be taken from a bag on the top shelf of a cupboard. All the other candidates must have used the ivory colour, which was still on the table. Because of the air conditioning the cream felt cold as it made contact with her face, a pleasant sensation. Once the foundation had been applied, the thick layer of powder hid the acne marks on the lower part of her cheek. It had been far better since she’d begun using the acid cream, but the scars were still visible.

Just before she left the make-up booth, through the crack in the door Lucinda caught a glimpse of the blonde girl leaving the studio with a sad smile on her face.

Moments later, the producer came up to where Lucinda was waiting and said:

‘You’re next, come in. What was your name again?’

‘Lucy.’

‘Please come in, Lucy,’ he said, placing his hand on her back and guiding her towards a door that had been painted black. They went in and the producer asked Lucinda to position herself within the white square formed by masking tape on the floor. Renato spoke in a soft, soothing voice while Lucinda attempted to avoid showing any signs of nervousness.

‘You need to look into the teleprompter, where the text is, see? You read straight off it, and it’ll look like you’re facing the camera. The text is all in French so our French teacher can assess your pronunciation’ – Renato pointed towards the teacher sitting next to the camera. ‘No need to rush, read slowly. We’ll control the prompter, so the text will scroll as you read it. Don’t move your body from side to side too much, but don’t stay completely still either. That way you’ll look more comfortable. Got it?’

Lucinda understood. She looked ahead, readying a half-smile.

‘Ready, Lucy?’

She nodded.

From the door, he announced:

‘Recording!’

While Lucinda read the text in the style of a class presentation, the producer looked through the open black door at the bench, where he saw a girl sitting alone. The last one. Then he could have lunch. He walked over to her.

‘Have you come for the screen test?’

The girl looked up from the drink in her hands.

‘No. I’m Viviana. Lucy’s sister.’

‘How old are you?’

‘Thirteen,’ she lied.

‘Do you study French too? Want to do the test?’

Viviana kept looking at him, motionless.

‘Go on, do the test,’ he said, pointing to the make-up artist’s door. ‘Make-up’s in there. You hardly need it. Go there and then straight into the studio. Wait, there’s someone in there now,’ he said, craning his neck. ‘You’re next.’

He held the clipboard out to Viviana. The permission form Cássia had signed for Lucinda was at the top.

‘Please fill this in while you’re waiting.’

There was a sneaky gap after Lucinda’s name into which Viviana’s would fit perfectly. She understood and began to write.

‘I don’t have an ID.’

‘No worries. Leave it blank.’

With his hands in his pockets he watched her fill in the form, then checked it and escorted her to the make-up room.

In no time at all she went from the test to that photo in the Sunday supplement, which got passed around the classrooms and toilets of the school over and over until it was a crumpled mess. The New Year fashion section showed Viviana with a glass of sparkling wine in her hand, toasting a blue-eyed model with a blond centre parting, his fringe falling to the sides and forming an M shape. Inside, Viviana’s brown shoulder blades were draped with a halterneck top, a single piece of glimmering cloth ending in a V shape that revealed her perfect little belly button as well as, somehow, the outline of her back. The pearlescent blouse, almost perforated by Viviana’s tiny breasts, formed a sharp contrast with her skin and her hair, which had been strategically gathered and draped over her shoulder. The same went for her brown hand with French tips resting in the gap in the boy’s white shirt, just below his first undone button. His chest was also brown, but from the sun, not naturally. It was also shaved: he must have been a swimmer. Or a rent boy.

• • •

Now Viviana was a thirty-one-year-old woman, and she was missing. The police didn’t care. As much as Lucinda feared she was the wrong person to be in charge of investigating her sister’s disappearance, there was no one else. As the car approached the highway, she feared she was heading to a confrontation, but she had to try.

PART I

BEFORE

1

LUCINDA

Lucinda wakes at dawn, without needing an alarm. She watches the piercing light slip through the edges of the blackout curtain, then turns over and reaches for her phone to check the time. The system has been updated overnight and the weather forecast for the day reads thirty-three degrees.

She looks over to the other side of the bed, where Nelson is sleeping. There isn’t the slightest possibility of her going back to sleep and even if there was she has to get up early today, so it wouldn’t be worth the effort. She can sleep more tonight, as much as she wants, because it’s Friday. She walks to the shower, removing her nightwear on the way.

On some days, such as today, she wakes kicking the air; it always happens at dawn. The anxiety leaves her legs twitching nervously. It’s a long-term problem and it had got a lot better after several treatments, including dental ones. But from time to time it mysteriously shows its face again.

She isn’t going to wash her hair so she ties it into a bun and covers it with a shower cap. She grabs the soap and lathers it across her body, under her armpits, beneath her breasts, on her neck, her face, before something makes her jump: it’s the alarm ringing out loudly from above the sink. She reaches out her hand, dries it on the towel and slides her finger over the mobile screen. It would have gone off again in ten minutes if she hadn’t gone to the effort of deactivating the whole sequence of alarms she’d programmed.

She gets dressed, eats an apple and makes some coffee. She won’t wake Nelson from his jealousy-inducing deep sleep.

She heads downstairs. Ten to seven. She contemplates the traffic, which is already coming to a standstill at Jardim Botânico, and darts between the cars going down the street. Anyone who saw her would think she was very eager to spend the next fifty minutes talking about herself to an accredited professional. But she’s only eager to make the appointment. Get there and be done with it.

Before entering the room she looks at the phone in her hand, aware that it’s time to switch it off, which she does. She sits down on the yellow-fabric sofa and the psychologist says, ‘Love the braid.’

She steadies herself so as not to reply ‘What, am I more “feminine” now?’ Or maybe the comment was intended as a provocation, to make her react exactly that way. She is incapable of reading that white woman with dark glasses, a few years older than her. She wonders again why she still goes. The setting, intended to be benevolent, the pastel-y tones of the decor; all of it rubs her up the wrong way.

But she needs to be good. She needs to try.

She starts talking. At least today she has a good opener.

‘I’m alone in Rio today. My mother and sister are travelling. To different places.’

‘For work or pleasure?’

‘Well, my sister’s doing some modelling somewhere – again. So I’m feeding her cat and watering her plants – again. Her apartment being near my work and all. My mother’s case is different; she almost never travels. She’s very focussed, a real workaholic. Her doctor forced her to take some time off. She’s gone to the Caribbean with two friends. So, pleasure.’

‘And what do you think about your mother’s trip?’

‘I think everyone needs to think about themselves from time to time. Deep down I think that’s what she was trying to do, in her own way. But eventually the body gets fed up.’

It’s always this way: at the beginning she doesn’t feel like talking, then she warms up and embarks upon a monologue until her time is up. That’s what’s happening now – yet again. After the door closes behind her, Lucinda turns her mobile back on. She walks out onto the street and heads home. She eats a cereal bar. Then she gets into the car and picks the traffic jam she wants to face today: the one near Rodrigo de Freitas Lagoon or the one facing the Corcovado Mountain. Not many options towards neighbouring Humaitá.

She enters the changing room and starts wrapping her fists. She likes to think of psychoanalysis as a prelude to a beating. ‘If you join the two together it’s super Jungian,’ she had once said, making Nelson cackle. But she’s semiserious. She needed to do things with her body for her mind to work properly, which was why she liked the two activities to be close together. So her Fridays consisted of a trip to a psychoanalyst at seven followed immediately by muay thai.

But does it have to be something so violent, her mother’s voice asks in her head? Yes. It would seem so. Since childhood she’d tried ballet, jazz dance, street dance, Olympic gymnastics, theatre, even a short spell learning various instruments (keyboard, both electric and acoustic guitar, the bass). Lucinda should have had a hunch, given how much she always liked judo and capoeira classes at holiday camps. Now she can remember how the other, smaller kids feared her and how she feared their fear. She found it crippling. Not any more. Now they were all adults, and no one was going to call her a bulldog or dyke for doing what her body demanded. And if they did, she could beat them to a pulp.

They warm up with ropes and jogging, then the tally series, then paired fights. Lucinda’s pair is the only other woman in the class, Taciana, a classic devilish blonde, even though the colour is artificial. She would almost be petite if her body were not a solid mass of protein-aided muscle. Today she’s wearing a red bandana emblazoned with mini skull-and-crossbones motifs. Lucinda isn’t afraid of hitting her.

She leaves the class thinking about travelling with Nelson. They could rent a cottage or a lodge in the mountains and just go. They’ve never done that. She takes her gloves off, picks up her bag from the small room by the tatami and walks downstairs to the women’s changing rooms.

Removing her robes, she looks at herself in the mirror, sweaty and unkempt in her puffy shorts and black and pink XL sports bra. She remembers the time she watched an MMA fight free of charge because Viviana was asked to be a ‘ring girl’, which meant holding up the signs announcing each round. She had worn the sex shop version of the male fighters’ kit: tiny, black body-hugging shorts with a little fake belt and a bikini top that lacked any real structure for her breasts, unlike the one Lucinda was removing now. Even so, Viviana had given the impression of looking a bit sweaty, or oiled-up, perhaps on the organisation’s orders, and had worn her hair in a pretty French braid that was, in fact, practical for fighting. Like the one Lucinda is wearing now.

She starts undoing it. She takes shampoo, conditioner, a comb and a towel from her bag and walks into the shower. She remembers when she first began to pick up on how life doesn’t treat everyone equally. Her mother, Cássia Bocayuva, was the daughter of a Maranhão notary public, the niece of a great lawyer and the cousin of several judges spread out across the country. A princess of the Brazilian legal profession. She had always been the ‘Bocayuva girl’, with all her male cousins, and no one found it strange when she also decided to go into that profession, although they did find it strange when she actually made up her mind to practise the law, not even considering the safest career choice for women of colour: studying hard for the civil servant exams that led to cushy, tenured judiciary jobs.

Cássia’s mother had died quite young, and even though she had studied at one of the best girls’ schools in Rio, which accepted this little mestizo girl after her father pulled rank, Cássia felt that the upbringing she had received at the school and from her nannies was insufficient, and she wanted her daughters to have everything she had lacked when it came to femininity. She pierced their ears when they were still babies, took Viviana and Lucinda to malls, bikini waxers and beauty salons – only the most exclusive and expensive, where the staff would praise their hair and skin before attacking them with chemicals, then once again before producing the bill. There were also trips to beaches, mushy romantic movies, music and language lessons, and volleyball – no other ball sports were allowed. It was the tried-and-tested way of becoming a woman, at least in the Rio de Janeiro of the time.

One day, a fourteen-year-old Lucinda came home with an eyebrow piercing. Cássia’s reaction was very different from what the girl had been expecting: instead of shouting at her or criticising her, she simply looked unperturbed. Her expression read: So smart… and yet she understands nothing. Such a shame. That was when Lucinda understood everything.

Previously Lucinda had thought that her mother’s plan was for her daughters to climb the social ladder in a way that she had never managed – becoming the most beautiful, the most popular and the coolest, until eventually they nabbed the most coveted matches and produced grandchildren. Femininity was a competitive sport, even between sisters. This was something Lucinda abhorred, with her 90s girl-power integrity and the excess weight she carried, which had the effect of covertly sidelining her from the game. In reality, the game was never meant to be played by these specific women. The three Bocayuvas had mestizo faces, dark copper skin and straight hair that fell like curtains over their faces. Lucinda was the only one to have inherited a certain waviness from her father, and spent a huge amount of time submitting herself to hydrations and relaxations to rein it in. The game being played by both sisters was that of appearing normal – in other words, white – just like almost everyone else at their school. Clearly, getting piercings didn’t help that. Even if it was just a silver stud, it wasn’t the same thing as her blonde classmate who had six hoops in her ears, as well as an extra one in her nose. Of course, when you’re a Barbie you can do what you like.

Lucinda gets out of the shower and, still naked, leans over to grab her mobile from the outside pocket of her rucksack. She unlocks it and stares at it, incredulous. It’s a photo. A photo someone has taken of their own erect cock, with her phone, while she was still in the class. A protrusion of yellowy-beige skin skewing to the left and a foot inside a brown leather shoe below it, standing on the dirty-white tiles in the room where everyone leaves their things. Lucinda had been the first to get there after the instructor.

She tries to recognise the footwear. Who was wearing leather shoes today? No one who actually works at the gym. Maybe someone else from the class. In her head she goes over all the unremarkable men she fights two or three times a week. She studies the yellowy and darkened regions across the body of the penis, suggesting an owner with skin of a similar colour. Pedro’s is pinky-white, Dênis’s a dark shade of black, Rafael’s brownish like hers. They were all eliminated. In terms of people with that shade of skin there was that boring lawyer… what was his name again? Régis. He could be the exhibitionist, except he always wears dark bottoms, and in the photo you can see a beige hemline over the brown shoe. Beige trousers and brown shoes is the outfit of someone who works in admin, or a public servant. As Lucinda sits down on the toilet seat and pulls her leggings on, she goes through names and faces in her head. Bruno. Telmo. Cristiano. Maurício.

The nutsack isn’t visible in the photo, Lucinda thinks, slowly raising her arms to do up her bra and then quickly lowering one of them to touch the screen so that it stays lit. If the balls were in the photo, looking at how wrinkled they were and how low they drooped could give away the age of the perpetrator, in which case she would accuse Cristiano, the only member of the class approaching sixty. Truthfully, though, he’s the least likely of the remaining suspects, because he probably wouldn’t know the trick of unlocking a phone by sliding up the camera icon, and besides, he wouldn’t be able to get a hard-on just like that, under pressure and on demand. She feels bad about thinking this atrocious chain of thoughts about her classmates. But that’s what it is, right? Exhibitionism. A crime in which the culprit wants to be discovered. And admired… for his virility, his ingenuity and his courage. Worse of all – it dawns on Lucinda – she’s doing exactly what he wants: trying to discover his identity. Perhaps even go after him.

As soon as she has this thought, she knows who it is: Bruno. Her neighbour. Of course. All those tubs of whey he is regularly seen removing from his car outside the building they both inhabit… and the obsession with body image – Bruno practised more than one martial art – and the indignation he must have felt at his chubby neighbour seeming uninterested in him, even when she was kicking him and throwing him to the floor. She didn’t know what she was missing out on… obviously. Lucinda feels a little disappointed with herself, annoyed at not having thought of him in the first place.

In her head Lucinda sees the car boot, the whey and a blonde woman walking around the car – girlfriend, wife, beach bimbo or the pretty white girl from the office, she doesn’t know and doesn’t care. The car belongs to her; so does the whey and the dick. If Lucinda wants, she can have a bit of that too. The image of degradation is complete.

She’s so distracted by the surprise dick she almost loses track of the time. She arrives at the studio panting and immediately starts helping the intern adjust the reflector before going over any items left on her to-do list and hurrying the guest through the corridor. Like all the programmes they shoot, this one is educational: an interview with software developers on the role of schools and universities in their work (unsurprisingly it had been extremely difficult to find anyone). When she’s finally let out for lunch, she notices there are six missed calls on her mobile. Number not recognised, São Paulo code. Must be telemarketing. She checks her notifications, likes a few posts and puts the device back in her bag.

She looks at the wall clock and discovers that she’s eaten lunch at eleven a.m., even earlier than usual. Public service does have its advantages, she thinks: although the blocks of time vary, the routine is more or less the same, and the lunch hour is actually an hour. It’s important to chew slowly, not just gulp the food down: that’s what causes the damage. She opens a packaged salad-in-a-cup while the warm part of her meal revolves in the microwave. She was a regular customer – addict would be more accurate – at the ten-real salad stand at a certain health food store, because it was the only way to force herself to eat right, given her non-stop lifestyle.

‘Crazy salad’, the label reads. Lucinda pours half the dressing over the leafy top layer and plunges the fork in to bring up the most interesting part from the bottom: shredded chicken, palm hearts and peas. She pours out the other half of the dressing, tosses the salad a little longer and starts to eat. She notices that her colleague Diane is eating a healthy-looking dish from a square Tupperware, consisting of okra, hummus and aubergine. Diane doesn’t like hot food. As soon as she’s finished, her colleague excuses herself and goes over to the window to smoke while Lucinda, after finishing her salad, begins cutting up her sad-looking chicken cannelloni and inserting pieces of it into her mouth.

‘Are you going to Marlene’s party, Cindy?’ Diane asks.

‘No, I never pitched in,’ Lucinda replies.

‘The third-floor team are super chilled.’

Lucinda looks askance at Diane and stops eating.

‘Not with me they aren’t, Di.’

‘What? The thing about the dress code?’

‘They called you Elsa and me Moana.’

‘That was just Silvia. The rest of them are cool. Running away isn’t the solution.’

‘Maybe it isn’t, but I’ve had enough.’

‘Come with me,’ puffs Diane. ‘If they tease you, I’ll tear their heads off.’

Lucinda chuckles.

‘I’ll think about it.’

As she washes her cutlery, Lucinda dwells on her notorious work nickname. As soon as the Disney film came out, people took to calling her Moana – to go with her blonde friend Diana, aka Elsa – and they made sure she knew it. The character was cute; the nickname, not so much. By using it her colleagues were saying: We see your difference, honey. There was also a hint of something sensual in the way they had turned a children’s character into a non-compliment that was essentially sexual in nature. It was like when Viviana had got called Tainá at school, around the time that film about the little Indigenous girl had come out. Lucinda hadn’t received this kind of nickname before; hers had always been openly insulting. She had had to wait until chubby child characters with naturally wavy hair became conceivable in pop culture to even be considered. Even then, she wasn’t happy about it.

Lucinda finishes eating and goes back to work. It’s desk work now, in front of a screen. As she sits down she feels her phone vibrate. She’s received a message, from the same São Paulo number. Telemarketing people don’t usually leave messages, as far as she knows. Intrigued, she presses play.

‘Lucinda? You OK? This is Graziane, I’m a friend of your sister’s, from São Paulo. Sorry to have called you so many times, but I’m kind of worried. Viviana and I had agreed to meet today and she hasn’t shown up. Do you know if she’s OK? Did she end up going back to Rio?’

Lucinda listens to the message again. The girl has a Paraná accent. She imagines a statuesque blonde, Eastern European origin. A model like Viviana. And with a name like that she must be from the country. Another message comes.

‘She hasn’t responded to any of my messages, not even to show that she’s read them, since last night. I’m worried. Let me know if you manage to get through to her.’

Could this be a trick? Some new scam? Lucinda decides to call her sister right away. She doesn’t pick up. Lucinda’s heart starts beating faster.

She sends text messages. She calls Viviana’s landline until it stops ringing. She calls her sister’s mobile nine times, and each time it goes straight to answerphone. As she leaves a message on Vivi’s voicemail she rushes to the disabled toilet on the third floor, gulping in huge mouthfuls of air before expelling them immediately. She bumps into Diane on the back stairs, smoking. She stubs out the cigarette on the floor with her shoe and grabs her shoulder.

‘My God, you’ve gone green,’ Diane comments, touching Lucinda’s arm.

Her hand is warm and dry as sandpaper. Lucinda continues to walk down the stairs, expels an ‘I feel sick’, pushes open the fire escape doors on the next floor down, shuts herself in the toilet and closes her eyes. No one will look for her there. It’s been a while since she had an attack of this kind, she thinks, touching her sternum to calm herself down – my God, it’s been years. But this one doesn’t feel like the earlier ones, which had no obvious trigger; this time the reason is entirely clear. She opens her bag and searches around for anything that might help her, medication, her diary, a notebook. As the objects fall to the floor one by one, the word PREMONITION appears in her head, written in a silver speech bubble, as if her brain needed to spell the thing out to make it real. Premonitions aren’t real, she thinks, but what is it? What was it?

Here’s what it is: Lucinda is certain Viviana has disappeared, really disappeared, that her lack of contact isn’t just a coincidence. She had left on Monday and planned to be back on Friday afternoon; over the four days of her sister’s absence, Lucinda only had to go to her apartment twice, that’s what they’d agreed. Yesterday, since feeding the cat and going home to sleep, she hadn’t communicated with her sister, not even to wish her a safe journey. Josefel and the plants don’t need another visit yet; they can go forty-eight hours without supervision. But today there are no notifications showing she’s read the messages, none of her calls have been answered, there isn’t a trace of Viviana at her place and she hasn’t sent a message saying she’s been held up. Something’s wrong. Something’s happened to her.

‘Something.’ She’s dead of course. In a ditch somewhere.